Depending on who you talk to, the mention of ‘Brexit’ will elicit quasi-Pavlovian reactions, ranging from mock insouciance to sheer despondency. To engage in Brexit-punditry may therefore seem hazardous or at best, cathartic (cf. Inglis Reference Inglis2017). Yet there could be some merit in this exercise, at least with regard to archaeology and heritage (see Gardner & Harrison Reference Gardner and Harrison2017; Pitts Reference Pitts2017; Schlanger Reference Schlanger2017; White Reference White2017; Bonacchi et al. Reference Bonacchi, Altaweel and Krzyzanska2018). Indeed, besides addressing the Brexit ‘neurosis’ attested by Kenneth Brophy, such an exercise should also help us to single out some underlying and as yet unidentified issues and threats. For all the risible bitterness of the situation (Beasley-Murray Reference Beasley-Murray2016), it seems crucial to figure out what is actually the ‘worst to expect’, if only to be able, upon this basis, to know how to ‘work for the best’; to rephrase the famous aphorism attributed to Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci: ‘pessimistic in analysis, optimistic in action’.

Should we then include the phenomenon of internet- and network-based social media—with the relationships that they entail between the past and new communication practices—among the ‘worst to expect’? I, for one, remain uncertain about the pertinence of the ‘Brexit hypothesis’—whereby any archaeological discovery can and will be enlisted for, or against, Brexit—as well as the solution proposed. Historians of archaeology and antiquarianism have repeatedly shown that the use and misuse of the past are often coeval—and, of course, not that easy to distinguish. They have further shown that archaeological erudition and expertise has long been prone to partisan appropriation and reinterpretation, from neo-classicism to neo-paganism, with a dose of Egyptomania and Von-Dänikenism in between. More is needed to pinpoint what is distinctive in terms of the messages, audiences and implications of the ‘new’ social media in question. After all, the history of humankind, from Aristophanes to television sitcoms included, is strewn with stridently proclaimed views—often half-baked and misinformed—including on historical or archaeological topics. So the puzzle here is not so much that the ‘People’, now avidly using social media, prove at times to be greedy, parochial, xenophobic or—the vilest affront—uninterested in the past (as noted by González-Ruibal et al. Reference González-Ruibal, González and Criado-Boado2018). Rather, it is the sentiment of disenchanted grief now affecting the liberal-minded archaeologists and heritage advocates among us, happy for so long to fuel social ‘impact’ indicators while relinquishing hard-earned ‘authorised’ expertise to the lures of bottom-up, re-empowered multivocality.

Reference to ‘the People’ and ‘empowerment’ should help us to look beyond the inconsequential musings of (some) social media users. The ‘dark side’ alluded to by Brophy is closer to home, as the problem of misrepresentation and misappropriation of the past is one that touches all of us—we the ‘experts’, the professional producers, promoters and protectors of archaeological heritage, be it within academia or the commercial sector. The root-causes of our predicament can, in fact, be traced to the slow but inexorable relocation of scientific knowledge within the market economy, with ensuing expectations of value for money in research programmes, the commodification of university education and the imperatives of quantifiable ‘impact’ (with consequences attested by Brophy).

Additionally, there are vulnerabilities specific to the recent history of British archaeology. The 2008 global economic crisis and the (ongoing) decade of ‘austerity measures’, for example, have played havoc with the UK's financial and legal commitments. For archaeology, this has included a sharp decline in professional expertise, watered-down protective regulations and weakened institutional capacities at both national and local levels—the latter, incidentally, where the bracing rhetoric of localism appears as an increasingly cruel provocation to financially asphyxiated local authorities (see assessments in Schlanger Reference Schlanger2013, Reference Schlanger2016). The proverbial boat was already heavily loaded when Brexit came along; this is probably why archaeologists and heritage professionals have thus far mostly focused their comments and reactions on their own ‘sectorial’ predicaments, be it regarding funding—how to replace the European manna, for example—or personnel—how to retain EU nationals, both academics and commercial field workers (cf. Schlanger Reference Schlanger2017; White Reference White2017; Fazackerley Reference Fazackerley2018; Masood et al. Reference Masood, Vesper and Noorden2018).

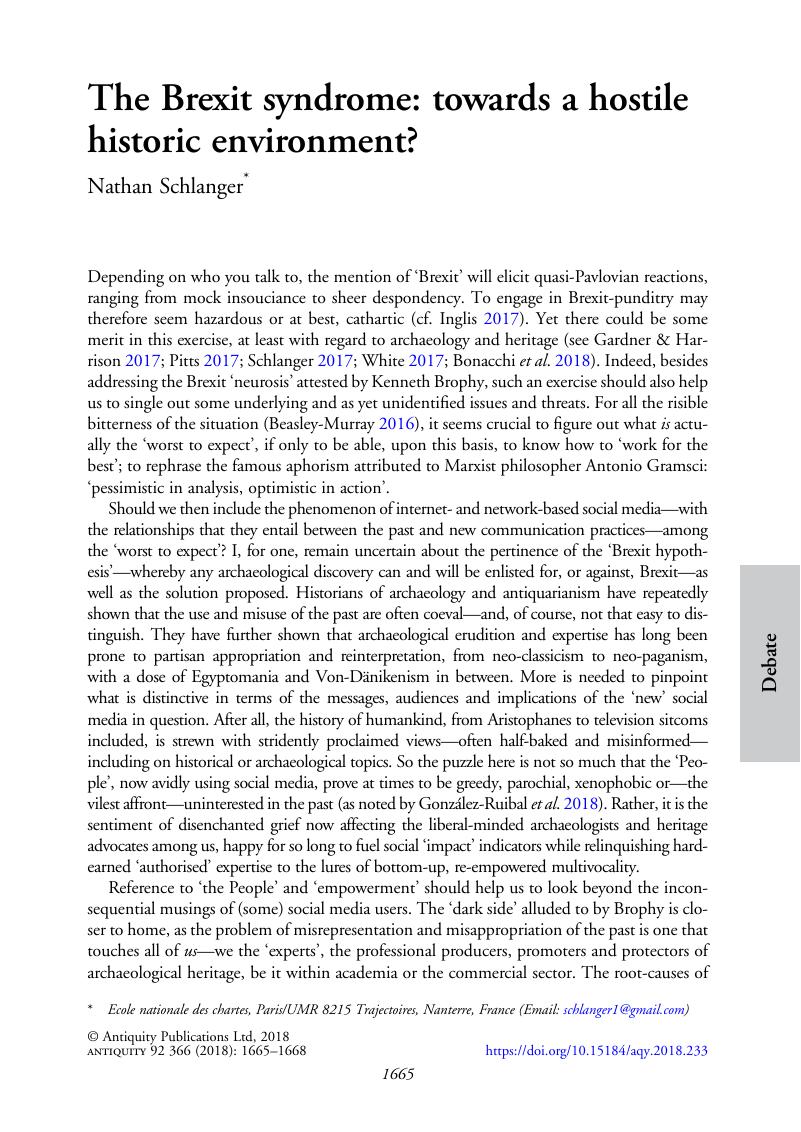

It may well be that ‘The crisis looming in two years’ time threatens to sweep away our status as a world leader’, as Gamble (Reference Gamble2018) bemoans. In addition, to these dire material risks, there are also some lurking intellectual and moral perils to be recognised and confronted. It is surely here that lies the ‘worst to expect’, against which we must be prepared: the probable aspirations of the local variants of ‘reactionary populism’—whose liberalism is strictly economic, rather than political or cultural (cf. González-Ruibal et al. Reference González-Ruibal, González and Criado-Boado2018)—that aim to ‘take back control’ of ‘our’ borders, ‘our’ laws and, indeed, ‘our’ heritage (see Figure 1; The Sun 2018). The worry here is not so much that archaeology in post-Brexit Britain will suffer from the authorities’ disinterest and disaffection (to the delight of developers). Rather, it is that it will be found of interest, and worth bolstering by proactive lobbies and newly legitimised interest groups in search of convergent historical narratives and compelling ‘sites of memory’—complete with iconic cues to the greatness that was and that will be ours again. Imagine that EU funding will be (partially, at best) replaced and distributed by a new arms-length governmental agency, with priorities and expectations quite different from the bland, but also innocuous, euro-speak of yesteryears. Imagine further that rich political party-donors team up to launch a grand plan dedicated—however indirectly—to the recovery of national pride and the enhancement of its local and global landmarks. Here are, in other words, the makings of a ‘hostile’ historic environment (in reference to the UK Home Office's ‘hostile environment’ policy for deterring immigration), with new requirements such as heritage commodification, public outreach (including social media) and new research agendas that emphasise the identification and celebration of ‘essential landscapes’, ‘sites of defiance and resistance’, ‘networks of expansion’, as well as, of course, renewed efforts to locate the ‘origins of the English’, be it at Boxgrove, Stonehenge and perhaps Blick Mead (but probably no longer at Cheddar Gorge, being somewhat disqualified by its aDNA evidence).

Figure 1. ‘Great Britain or great betrayal?’ Front page of The Sun, 12 June 2018. A collage of British icons on a background of rolling hills. Clockwise from top right: the Red Arrows, the Angel of the North, the Loch Ness monster, football, Alton Towers, the Shard, a Mini Cooper, a London double-decker bus, a fish and chip shop, Stonehenge, a Spitfire, Windsor Castle, Westminster Palace, Ferrybridge power station and a seagull. (Image copyright The Sun, and News Licensing and News UK, published under non-commercial fair use, after requesting permission 11 September 2018.)

‘Project fear’ for archaeologists? Dystopia? Let us hope that these appalling prospects never materialise! But archaeologists in Britain should, nonetheless, brace themselves for the possibility that their earnest efforts might be enlisted by forces darker than the ebbs and flows of mere social media and that they might, from now on, have to watch their words and exercise restraint and self control—also regarding the enticements of lavish funding and global status. This resistance applies to the ways that they present and promote their wares, ensuring that their discoveries are not appropriated outright for some societal ‘impact’ that they do not sanction and over which they have no control. Thus, when attempting to ‘work for the best’, our guiding question should not be merely ‘what can we do, each one of us?’, as Brophy (Reference Brophy2018) recommends, but rather, adopting a more committed and collective approach, ‘what can we do, together?’ How to stand shoulder to shoulder—academic and commercial archaeologists alike, not forgetting the museum sector, culture and the arts—to ensure that statuary obligations are upheld, that heritage management remains viable, that scientific expertise, epistemic authority and moral integrity are maintained; and indeed that the past we discover, produce and disseminate does not end up as yet another tabloid trophy—or yet another cardboard monument in the heritage theme park of the proffered ‘Festival of Britain 2022’—for ‘leveraging’ the image of post-Brexit Britain.