Introduction

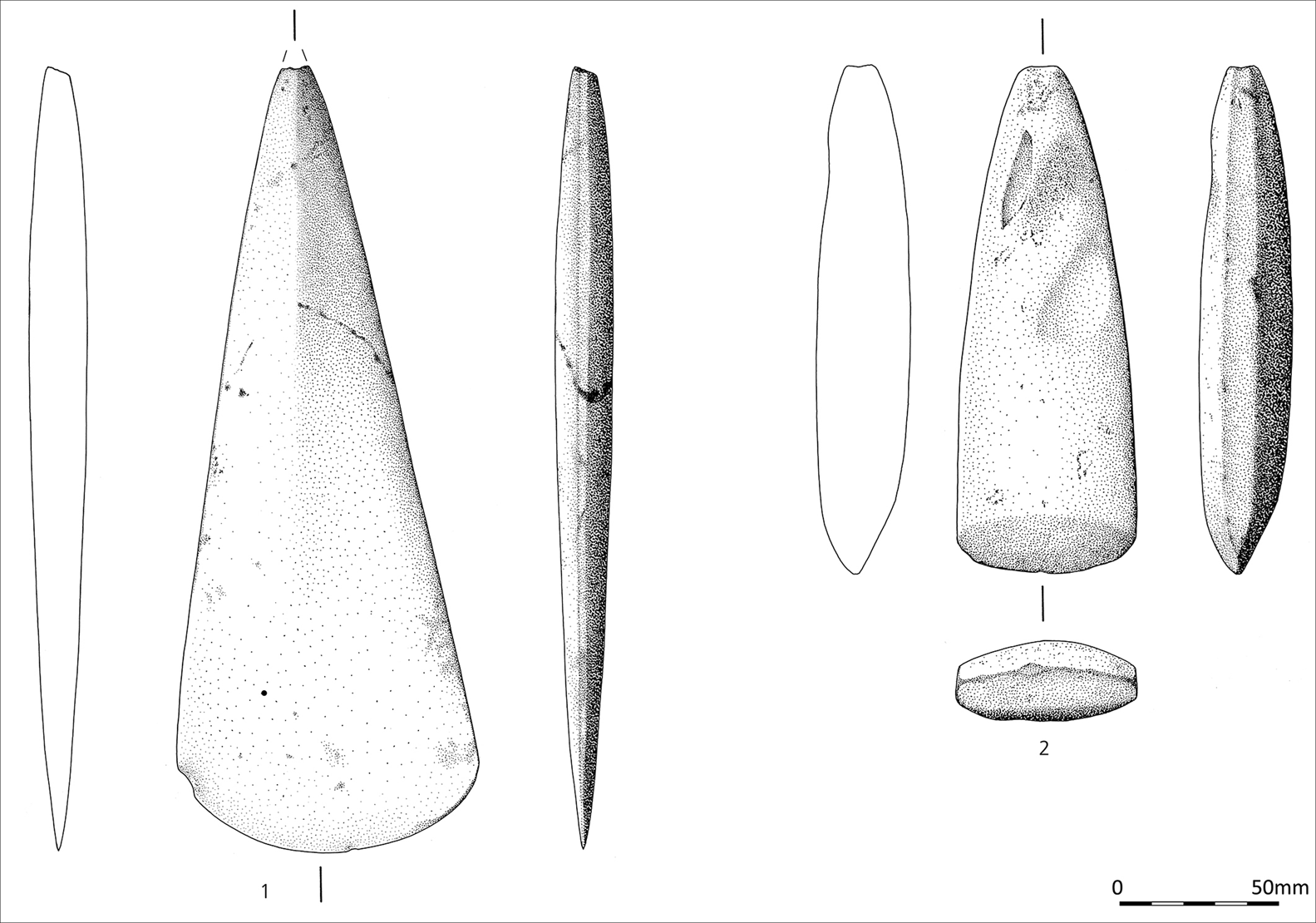

The site of Kapellenberg (Figure 1), situated on a promontory extending from the Taunus low mountain range in western central Germany, and overlooking the northern Upper Rhine Valley (Figure 2), has been known since the end of the nineteenth century both for its well-preserved ramparts and two large Neolithic stone axe-heads (von Cohausen Reference von Cohausen1893).

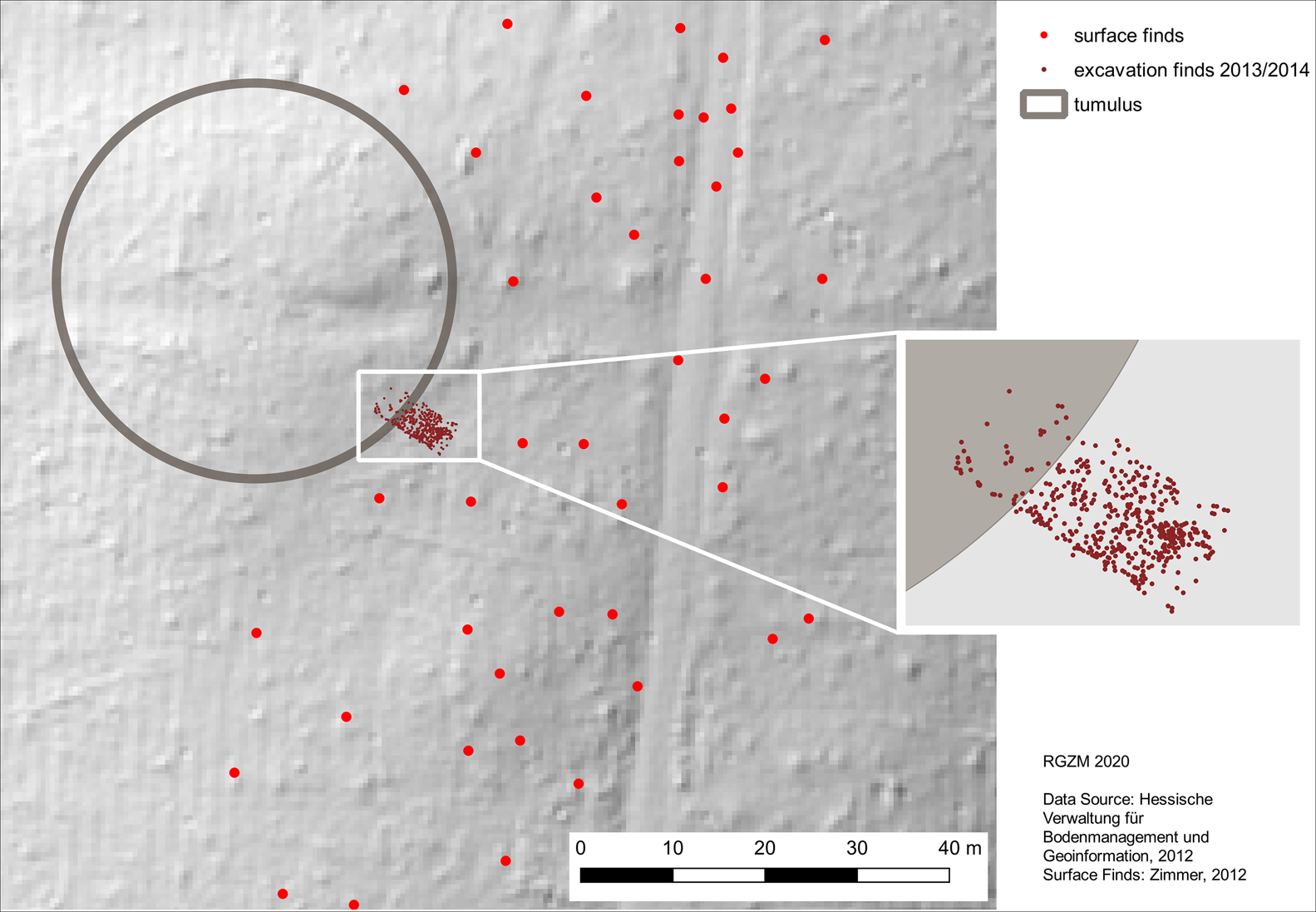

Figure 1. Kapellenberg: inset shows tumulus with nineteenth-century trench and two adjacent Late Neolithic mounds (figure credit: A. Cramer).

Figure 2. Map showing hypothetical exchange routes and salt sources in the region (figure credit: N. Antunes, D. Gronenborn & M. Ober).

In recent years, the site has become the focus of a joint research project of the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum (RGZM), the Johannes-Gutenberg University in Mainz, the state conservation agency of the German Federal State of Hessia, and the Magistrate of the City of Hofheim (www.rgzm.de/kapellenberg). Research at the site revealed that the promontory has been occupied intermittently from the late Middle Neolithic (4500–4300 cal BC) onwards (Zimmer Reference Zimmer2012). Middle Neolithic Michelsberg occupation and the rampart-and-ditch system was established around 4100 cal BC, and continued sporadically until after 3600 cal BC, when the site was fully abandoned. Kapellenberg is the best-preserved Michelsberg enclosure system, and also one of the largest, with an intramural area of 23ha.

The tumulus

In the course of the current research project, a hitherto undetected surface feature was discovered by on-site inspection and lidar scans. This took the form of an extensive anthropogenic mound with a diameter of 90m and a maximum height of 6m (Figures 1 & 3–4). A test excavation in the centre of the feature showed that it consisted of boulders and soil extracted from the subterranean geology. The mound was apparently erected on a natural rise in the local bedrock (Hofheim gravel). Coring profiles showed that the preserved height of accumulated material is about 1m (Figure 3).

Figure 3. 3D-section through tumulus based on lidar scan, excavations, and coring (three-fold vertical exaggeration) (figure credit: A. Cramer, M. Ober, H. Thiemeyer & P. Pétrequin).

A visual inspection of the ground's surface prior to the excavation and lidar scan revealed traces of a rectangular trench at the centre of the mound; re-excavation of this area produced three coins dating to 1872 and 1875 (Figure 3). These coins, together with evidence from local archival material and a review of the initial publication of the two axe-heads, suggest that the axe-heads were found during an undocumented nineteenth-century excavation that might well have destroyed the original burial situation. At that time, the mound was not recognised as a separate feature and the rubble had instead been interpreted as associated with the Michelsberg rampart system (von Cohausen Reference von Cohausen1893).

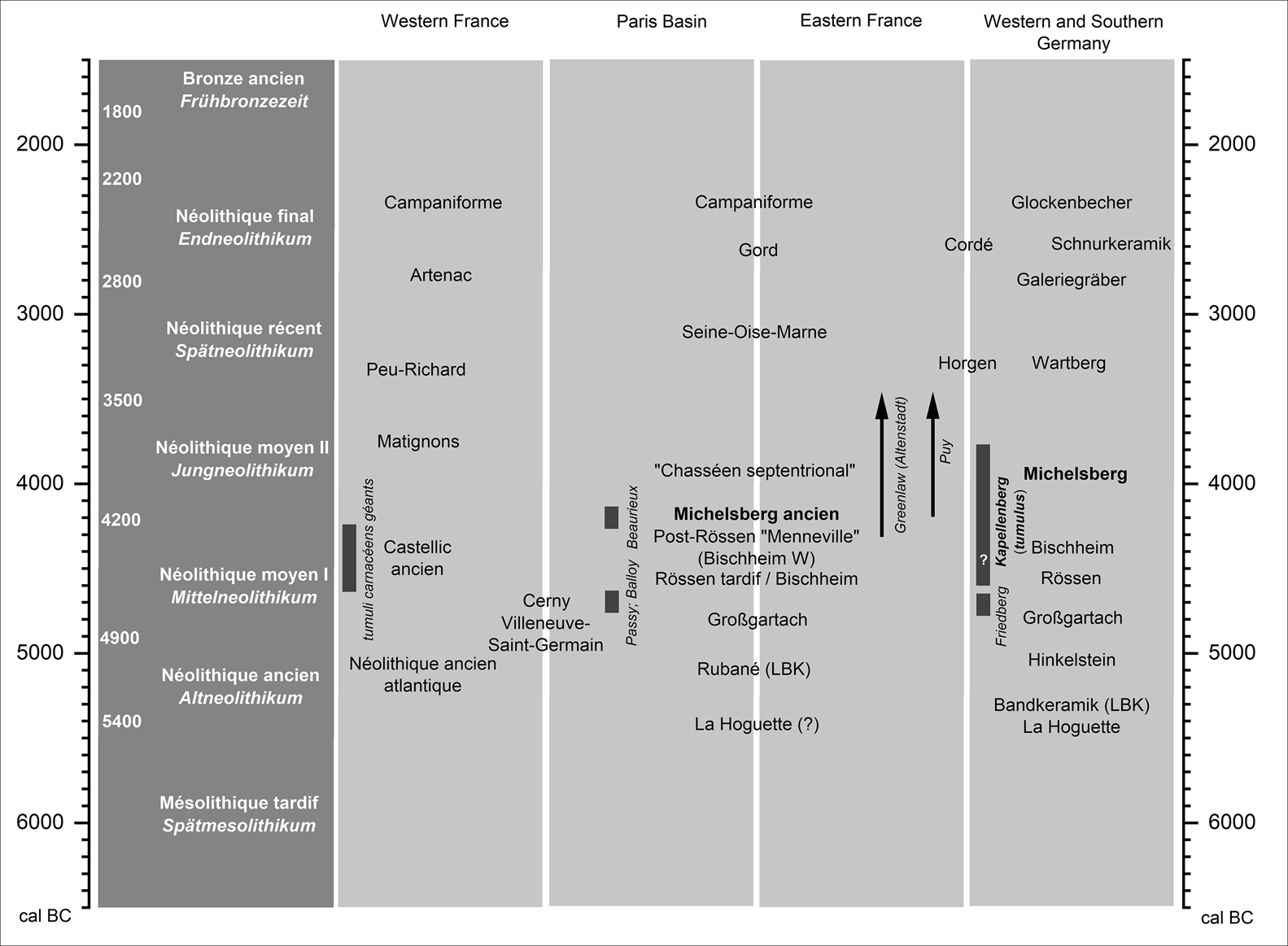

Osseous material is not preserved at Kapellenberg, nor was any organic material recovered during re-excavation. It was thus not possible to date the mound directly. The occupation phases of the site and its stratigraphy help narrow down its construction date, however. The late Middle Neolithic occupation (4500–4400 cal BC) constitutes the terminus post quem for construction, while the terminus ante quem is established by the stratigraphy in a trench close to the mound. From this it is evident that the tumulus had largely eroded by the time the most extensive interior occupation had begun around 3750 cal BC (Figure 4). Therefore, it seems justified to propose a late Middle Neolithic or early Michelsberg construction date for the mound (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Distribution map showing surface and excavated finds in the vicinity of the tumulus. The finds, dating mostly between 3750 and 3650 cal BC, and tumulus are stratigraphically almost mutually exclusive (figure credit: A. Cramer & D. Gronenborn).

Figure 5. Simplified chronological table showing lifespan of the two axe types and dating of the tumulus (figure credit: D. Gronenborn & P. Pétrequin).

The stone axe-heads

This time frame is also supported by the typology of the axe-heads (Figure 5): one is made from Alpine jade (Mont Viso massif, Poco Valley) and is of the Altenstadt-Greenlaw type. The second, made from amphibolite of unknown origin, is of the Puy type. The Greenlaw type appears around the middle of the fifth millennium in the jade axe deposits of Brittany, while the Puy type appears c. 4300 cal BC in Italy, and c. 4100 cal BC in the French Jura (Figure 6). This time range corresponds to the expansion of the Michelsberg Culture from the northern part of the Paris Basin to the Rhine Valley (Jeunesse Reference Jeunesse, Biel, Schlichterele, Strobel and Zeeb1998).

Figure 6. Axe blades: 1) jade blade, type Altenstadt-Greenlaw (JADE_2018_0235); 2) amphibolite blade, type Puy (Hofheim 14429) (figure credit: M. Ober).

Alpine jade axes found in monumental tumulus-type tombs are rare in Western Europe, the epicentre of the phenomenon being the Gulf of Morbihan in Brittany and, to a lesser extent, the central Paris Basin (Pétrequin et al. Reference Pétrequin, Cassen, Errera, Klassen, Sheridan, Pétrequin, Errera, Klassen, Sheridan and Pétrequin2012a & Reference Pétrequin, Cassen, Gauthier, Klassen, Pailler, Sheridan, Pétrequin, Errera, Klassen, Sheridan and Pétrequinb). Kapellenberg is the only known circular burial mound dating to the late Middle Neolithic or early Michelsberg Culture in western Central Europe. Michelsberg high-status burials have been discovered in the Beaurieux Valley in France, but these are elongated earthen barrows, possibly reminiscent of mounds of the Cerny Culture (Colas et al. Reference Colas, Manolakakis, Thevenet, Baillieu, Bonnmardin, Dubouloz, Farrugia, Maigrot, Naze, Robert. and Besse2007).

Long-distance connections and political differentiation

Circular burial mounds constructed with stone boulders are known only from Brittany (Boujot & Cassen Reference Boujot and Cassen1992). There, the so-called tumuli carnacéens géants date to the Castellic ancien, ranging from 4680 cal BC to 4240 cal BC (Cassen et al. Reference Cassen, Boujot, Dominguez-Bella, Guiavarc'h, Le Pennec, Prieto Martinez, Querre, Santrot, Vigier, Pétrequin, Errera, Klassen, Sheridan and Pétrequin2012a; Schulz Paulsson Reference Schulz Paulsson2017: 38).

Long-distance connections between Central and Western European regions are already documented for the preceding Middle Neolithic. These are demonstrated by high-status burial evidence (Cassen et al. Reference Cassen, Boujot, Dominguez-Bella, Guiavarc'h, Le Pennec, Prieto Martinez, Querre, Santrot, Vigier, Pétrequin, Errera, Klassen, Sheridan and Pétrequin2012Reference Cassen, Boujot, Dominguez-Bella, Guiavarc'h, Le Pennec, Prieto Martinez, Querre, Santrot, Vigier, Pétrequin, Errera, Klassen, Sheridan and Pétrequina; Gronenborn et al. Reference Gronenborn, Strien, van Dick, Turchin, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018), and by jade axe-head distribution patterns (Pétrequin et al. Reference Pétrequin, Cassen, Klassen, Pétrequin, Errera, Klassen, Sheridan and Pétrequin2012c), suggesting that they may represent exchange networks of prestige goods associated with elites. Another important component of these networks may have been the production and exchange of salt over long distances (Weller Reference Weller and Weller2002; Cassen et al. Reference Cassen, Vigier, Weller, Chaigneau, Hamon, de Labriffe and Chloé2012b).

The Kapellenberg tumulus indicates that a socio-political hierarchisation process linked to the emergence of high-ranking elites, which was under way in Brittany and the Paris Basin during the earlier to mid fifth millennium (Cassen et al. Reference Cassen, Boujot, Dominguez-Bella, Guiavarc'h, Le Pennec, Prieto Martinez, Querre, Santrot, Vigier, Pétrequin, Errera, Klassen, Sheridan and Pétrequin2012a; Pétrequin et al. Reference Pétrequin, Cassen, Errera, Sheridan, Tsonev, Turcanu, Voinea, Manolakakis, Schlanger and Coudart2017; Gronenborn et al. Reference Gronenborn, Strien, van Dick, Turchin, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018) had extended into western Central Europe, possibly within a peer-polity interaction framework and maybe also in the course of population shifts from France to Germany (Beau et al. Reference Beau, Rivollat, Réveillasm, Pemonge, Mendisco, Thomas, Lefranc and Deguilloux2017).