Domestic interiors created during the Aesthetic Movement have come under intense scrutiny by contemporary scholars. Designers such as E.W. Godwin (1833–86), Christopher Dresser (1834–1904) and Thomas Jeckyll (1827–81) have been studied for the extent to which their work seems to realise ideas of aesthetic autonomy associated with Théophile Gautier (1811–72), Walter Pater (1839–94) and Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848–1907).Footnote 1 According to this line of approach, the aesthetic interior participated in a cult of beauty divorced from morality and utilitarian needs.Footnote 2 Some of these interpretations have gone as far as to align the Aesthetic Movement with ‘decadence’, seeing the terms as virtually synonymous.Footnote 3

This essay takes a different tack by analysing the aesthetic interior in the light of concerns for health reform. In particular, I discuss the work of architect and designer E.W. Godwin, described by his friend and client Oscar Wilde as ‘one of the most artistic spirits of this century’.Footnote 4 In tandem with his aesthetic idealism, Godwin was a committed reformer who saw the well-designed domestic interior as an incubator of physical health and mental well-being. He pursued interior design as a means to foster a healthy life, one based on hygiene, relief from urban stress and a quickened aesthetic sensitivity. He conceived of spare and calm interiors that offered sanitary and healthful alternatives to dust-infested Victorian clutter while concomitantly offering psychological respite from the ‘high-pressure, nervous times’ endemic to metropolitan life.Footnote 5 These goals accord with Godwin's related interest in dress reform, a preoccupation that led to his participation in London's International Health Exhibition of 1884, for which he wrote a handbook on dress in relation to health and climate.

Inevitably, there are discrepancies between Godwin's stated intentions and his actual achievements as a reform-minded designer. Nevertheless, what will emerge, I hope, is a clear connection between the aesthetic interior and the central imperative of sanitary reform: promoting health through ameliorating Britain's urban environment. As foremost architect of the Aesthetic Movement, Godwin pursued the environmental focus of the sanitarians at the level of domestic design while expanding their meliorative mandate to encompass artistic criteria. Situating Godwin in this context will help clarify his specific contribution to the sanitary debates and measures that prevailed in Britain during the second half of the nineteenth century. This essay thus builds upon earlier studies by Annmarie Adams, Eileen Cleere and Judith Neiswander in emphasising a continuum between Aestheticism and hygienist discourse.Footnote 6

PUBLIC HEALTH AND DOMESTIC REFORM

One of the tropes, in fiction, of the aesthetic interior is the idea of the private home as a retreat into the self, the realm of unfettered subjectivity if not of neurotic introspection. This leitmotif characterises texts as diverse as Edmond de Goncourt's Maison d'un artiste (1881), Joris-Karl Husyman's A Rebours (1884) and Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890).Footnote 7 For Godwin, however, it was the fundamentally practical and hygienist issues of light, air and cleanliness that were at the forefront of his intention to improve domestic design.Footnote 8 He lived in an age when there was a growing awareness of the need to attain adequate sanitary conditions in the Victorian home.Footnote 9 Urban growth had increased the spread of diseases and created new challenges for public health.Footnote 10 Cholera epidemics afflicted London in 1831–32 and 1848–49, while throughout the century diseases such as smallpox, typhus, and tuberculosis (commonly referred to as consumption) caused high death rates among the metropolis's working class.Footnote 11 In particular, cholera – a water-borne disease – killed tens of thousands swiftly and suddenly, frightening the population with its rapidity of spread, and stirring municipal corporations into taking active measures to improve sanitation.Footnote 12

These epidemics led to one of the greatest public works' projects of the era: the creation of an underground sewer network, overseen by the civil engineer Joseph Bazalgette (1819–91), which was instrumental in protecting the city from a recurrence of cholera.Footnote 13 A particular motivating force was the ‘Great Stink’ of 1858, when hot weather exacerbated the stench of untreated human waste and industrial discharge flowing into the Thames. Bazalgette devised a network of main sewers running parallel to the Thames that would intercept surface water and waste from street sewers, which had previously emptied directly into the river.Footnote 14 On top of the intercepting sewer serving west London, he built two granite-faced embankments, the Victoria Embankment, completed in 1870, and the Chelsea Embankment, completed in 1874 (Fig. 1). Combined with the Albert Embankment on the river's south bank, the Thames Embankment reclaimed over fifty acres of land from the river to create parks, roads, and esplanades, which constituted some of the century's most important interventions in London's built environment.Footnote 15 Such public works made visible the country's staunch commitment to sanitary improvement for its citizens.

Fig. 1. Chelsea Embankment towards the Albert Bridge, 1873 (© Historic England Archive, ref: OP04624)

In addition to works of civil engineering, Great Britain promulgated numerous laws addressing sanitary reform. These legislative acts were set into motion following the publication in 1842 of a major document on the state of public health: Edwin Chadwick's Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain, a study begun in 1839. Chadwick advocated the benefits of sunshine, fresh air and cleanliness to underpin a broad programme of civic hygiene. The immediate outcome of his Report was the Public Health Act of 1848, the first time that the British government charged itself with the responsibility to safeguard the health of its population.Footnote 16 The Act brought about regulations related to the supply of water, sewerage, drainage, street cleansing and road paving.Footnote 17 It established a General Board of Health with jurisdiction over a country-wide series of municipal boards. The subsequent Public Health Act of 1872 created a London Board of Health intended to oversee how local authorities regulated local hygiene.Footnote 18 A further act in 1875 required new residential buildings to include running water and internal drainage.Footnote 19 Separately, a series of Factory and Workshop Acts passed between 1850 and 1901 ameliorated working conditions.

For the most part, the larger societal implications of hygiene did not interest Godwin and he had a mixed track record when venturing into schemes with a public scope for sanitary reform. During the 1870s he embarked on a trio of projects that evince these mixed results, the most important of which was his design for houses in Bedford Park, a planned community in Chiswick in west London, which is often considered the first garden suburb.Footnote 20 In 1875, the developer Jonathan Carr had commissioned Godwin to design, as prototypes, a detached house and a pair of semi-detached houses (Figs 2 and 3) for the community that he would later advertise as ‘the healthiest place in the world.’Footnote 21 This claim was based not only on the suburb's leafy location, safely distant from London's slums, but also on its use of some of the ideas of Benjamin Ward Richardson, one of the pioneers of the sanitary movement,Footnote 22 a figure trained as a physician, who had founded the first journal dedicated to public health and had helped establish examinations for sanitary inspectors.Footnote 23 At a lecture in 1875 in Brighton, which Chadwick attended, Richardson described a utopian city called Hygeia, planned to optimise health for its inhabitants.Footnote 24 Prescriptions for healthy dwellings included limiting heights to four storeys, doing away with basements and cellars in favour of ventilation spaces beneath houses, using glazed brick as a washable material for walls, and placing the kitchen on the uppermost floor, under a flat roof, which could serve as a platform for a garden.Footnote 25

Fig. 2. Nineteenth-century photograph of houses designed by E.W. Godwin and Coe & Robinson in Bedford Park (Harvard University, Henry Hobson Richardson Photograph Collection, vol. 218-7, seq. 34; courtesy Harvard Graduate School of Design, Frances Loeb Library)

Fig. 3. Nineteenth-century photograph of detached house designed by E.W. Godwin in Bedford Park (Harvard University, Henry Hobson Richardson Photograph Collection, vol. 218-7, seq. 43; courtesy Harvard Graduate School of Design, Frances Loeb Library)

For Carr, Godwin designed compact houses that incorporated a number of these features, including the abandonment of basements, bathrooms with hot and cold running water, and rooms fitted with glazed tiles to facilitate cleaning.Footnote 26 Carr eventually replaced Godwin with Richard Norman Shaw, who was acclaimed not only as a designer but also as the inventor of an ingenious method of ventilating soil pipes at his own house in Ellerdale Road, Hampstead.Footnote 27 Godwin, by contrast, left actual experiments in plumbing to his architectural peers and other professionals. It was similarly Philip Webb and not Godwin who became a member of the Sanitary Institute, an organisation founded in 1876 to promote practical applications of public hygiene.Footnote 28

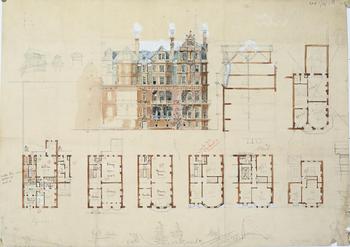

In 1877, Godwin designed three houses on the Chelsea Embankment, which – while not directly involved with Bazalgette's infrastructural project – took advantage of the improvements in London's built environment that followed the engineer's interventions (Fig. 4). The furnishers Gillow and Company commissioned him to design three adjacent houses as a speculative venture aimed at wealthy tenants who would appreciate a riverside location now that sewage no longer discharged directly into the Thames.Footnote 29 Godwin's preliminary plans for the central one of these dwellings shows generously proportioned windows facing the river, an internal staircase illuminated by a rooftop lantern, a dumbwaiter between the kitchen and dining room (one of Richardson's recommendations for houses in Hygeia) and, on each of the principal bedroom floors, a commodious bathroom with tub, sink and separate water closet.

Fig. 4. E.W. Godwin, preliminary designs for houses for Messrs. Gillow, 4–6 Chelsea Embankment, London, 1877; pencil and coloured wash (courtesy Royal Institute of British Architects, British Architectural Library Drawings Collection, ref. 12563)

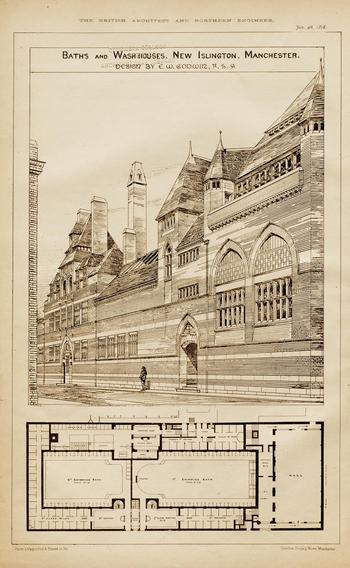

In 1877, Godwin, an enthusiast for Turkish Baths, submitted a competition design for a public baths and washhouse in Manchester (Fig. 5).Footnote 30 Parliament had passed a Baths and Washhouses Act in 1846 to encourage local authorities to construct such facilities, and Manchester prepared a brief calling for a single building that would contain two swimming baths, separate first- and second-class changing areas, and a public laundry, in addition to a superintendent's residence.Footnote 31 Although his scheme was praised in the pages of The British Architect, his entry was not selected, and Godwin does not seem to have entered any other competitions relating to public health.Footnote 32 Instead, he focused on the domestic realm, where he was able to address health-related concerns through specific designs and topical articles intended to strike a chord with his potential clientele: the educated middle class with cultural aspirations.Footnote 33 For him, the domestic interior became a healthy city in miniature, which he achieved by adapting the public health agenda initiated by sanitarians such as Chadwick in the 1840s and 1850s in ways that would resonate with his own middle-class clients of the 1870s and 1880s.

Fig. 5. E.W. Godwin, competition entry for Baths and Wash-houses, New Islington, Manchester; as published in The British Architect and Northern Engineer, 4 January 1878 (courtesy Columbia University in the City of New York, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library)

The efforts of sanitary reformers have been described as a combination of evolving concerns and practices.Footnote 34 Such a categorisation also applies to Godwin in his dual role as designer and writer. He repeatedly addressed the topic of hygiene in his prolific writings as a journalist and architectural critic, at the same time as he was designing interiors intended to reduce dust and dirt, maximise fresh air and promote well-being. In so doing, he participated in a broad, society-wide discourse that linked hygiene with aesthetics.Footnote 35 His views were also shared by others, such as the architect R.W. Edis and the authors Lady Mary Anne Barker and Mary Eliza Haweis who broached the topics of cleanliness, sanitation and ventilation in their books on domestic decoration.Footnote 36

Britain's sanitation movement focused on the health of the urban middle class and saw improving domestic design as tantamount to a form of preventive medicine.Footnote 37 As Annmarie Adams has discussed, medical professionals sought to educate middle-class householders very much as part of a robust public health strategy. Eventually, some physicians even set themselves up as ‘building doctors’, extending their expertise to the architectural profession, as they endeavoured to diagnose faulty drainage, inadequate ventilation or poor lighting in the homes of their patients.Footnote 38 In 1880, for example, Dr George Wilson of Edinburgh published a book, Healthy Life and Healthy Homes, that had confident assertions about the health benefits of proper ventilation and well-designed plumbing traps and recommended the best ways to illuminate rooms.Footnote 39 What is entirely missing from Wilson's book, however, is any inkling of how these hygienic desiderata could be incorporated into a cogent work of design.

Godwin participated in such a society-wide discourse but he sought to restore authority in design issues to architects. This imperative underlines two series of articles he published in 1876 about decorating his own London residences: ‘My Chambers, and What I Did to Them’, followed by ‘My House “in” London’.Footnote 40 Serialised in The Architect, one of the leading professional periodicals of the era, these articles highlighted the author as an expert in adjudicating what was best for an exemplary urban dwelling. Writing in the first person, he interweaves the aesthetic and the utilitarian as he takes his readers through each room of his residences, explaining the reasons for all his design decisions while exemplifying the ‘self-help’ ethic promulgated by sanitarians.Footnote 41 During an era in which ‘sanitary visitors’ inspected urban dwellings,Footnote 42 he was in effect opening each room of his home to public scrutiny. As if taking a leaf from Chadwick's era-defining Report, he strove to ‘secure light, air, and cleanliness’ in the domestic realm.Footnote 43 Cleanliness should be ‘the first consideration in all domestic design’, he declared, as he railed against the ‘dust traps’ and ‘villainous smells’ of unwholesome interiors.Footnote 44 London itself, he asserted, had an ‘atmosphere charged with dust’.Footnote 45

Godwin's abhorrence of dust was in line with the two prevailing theories about the origin and spread of disease: the miasmatic and germ theories. The miasmatic theory of ‘bad air’ as the origin of most maladies had dominated sanitary discourse at mid-century and was slow to yield to the newer germ theory of biological contagion.Footnote 46 Despite the discoveries by Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch of micro-organisms as the causes of disease, many prominent sanitarians, including Richardson, were reluctant to jettison their steadfast belief in the environmental origin of illness.Footnote 47 Consequently, as Eileen Cleere has noted recently, the two theories overlapped and circulated in an uneven and fitful way throughout the 1870s and 1880s.Footnote 48 In 1883, for example, Richardson was still claiming that habitations were the cause of disease as he fulminated against ‘the evils of dust’ in domestic interiors.Footnote 49

HOUSES ‘IN’ LONDON: THE HOME AS HYGIENIC LABORATORY

In his two-part article ‘My Chambers, and What I did to Them’, Godwin described alterations to the bachelor chambers he rented after moving from Bristol to London, following the early death of his first wife, Sarah, in 1865.Footnote 50 It is known that Godwin leased 197 Albany Street, Regent's Park, from 1867, so this this could be the address of the chambers he describes. Footnote 51 It is still conceivable, however, that his article discusses a composite of several interiors he renovated over the course of his career. Whatever the case may be regarding a factual correspondence between his descriptions and an actual residence, he emphasised how he strove for effects of simplicity, delicacy and refinement, all with an eye to practicality and ease of cleaning. The Albany Street location, one block away from Regent's Park, would have also appealed to him for its proximity to fresh air.Footnote 52

The architect's quarters consisted of a central hall with drawing and dining rooms at the front of the house, facing south-west, and a bedroom and servant's room at the back looking north-east, along with compact spaces for pantry and larder.Footnote 53 In the front rooms, one of his first alterations was to remove the existing serge curtains because the fabric was a magnet for dirt and grime. ‘Serge in London, no matter how admirable the colour’, Godwin wrote, ‘is a dust-holding grimy-to-the touch sort of fabric’.Footnote 54 Instead, he ran up new curtains out of chintz since, as a glazed cotton fabric, it was easier to clean than the heavy worsted of serge. His changes to floor coverings were similarly intended to optimise dust removal:

Regarding fluff and dust in rooms as two of the greatest enemies of life, it was a matter of conscience to have the carpets sufficiently small and free to be easily removed for beating. In one room – the dining room – the margin of the floor to the extent of three feet was stained and varnished…. In this room, there was a square, or nearly square, Turkey carpet, the border of which was entirely free of the wall furniture, such as buffet, book-cases, cabinets, &c…. The bedroom floor was left bare except a rug at the side of the bed and two eastern mats.Footnote 55

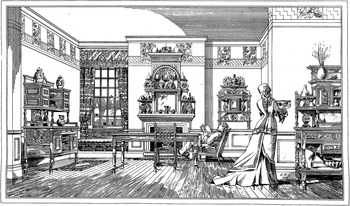

Godwin gave the carpets sizes so they would be set in from the ‘wall furniture’ – that is, pieces located around the perimeter of the room. Limiting the extent of carpets over wood floors had also been one of Richardson's recommendations for houses in Hygeia.Footnote 56 Images do not survive of Godwin's rooms, but we may get an idea of them from the illustrations in the Art Furniture catalogue published by cabinet-maker William Watt in 1877.Footnote 57 Featuring Godwin's designs, the interior perspectives – one of which Godwin had already published in The Building News in 1876 – show sparely-furnished rooms with small rugs and large expanses of wood flooring, and with thin-legged furniture standing high off the floor (Fig. 6). This facilitated ease of cleaning underneath them, while castors allowed furniture to be moved without the aid of servants.Footnote 58 Such illustrations of orderly, well-illuminated and easy-to-clean rooms should be read against a background of the sanitarians’ exposés of ‘fever nests’ – overcrowded living spaces, dark and airless, rife with filth and disease, as was commonplace throughout London's poorer districts.Footnote 59

Fig. 6. E.W. Godwin, interior perspective of a dining room; as published in The Building News, 17 November 1876 (courtesy Royal Institute of British Architects, ref 10068)

Godwin was clearly aware of poverty in London; and some of his remarks reveal that he, like many of his contemporaries, associated slovenliness with indigence. Walking through side streets in Bloomsbury, for example, he observed terraces that were ‘almost wholly given up to a poor class of lodging-house keeper’.Footnote 60 He anxiously took note of ‘street after street and square after square’ that seemed to be ‘sinking lower and lower’ to the depths of ‘the low lodging-house’. Dirt and grime on the architectural features of these buildings were, for him, tell-tale signs of penury, as ‘every moulding is choked with dirt and every fragment of carved ornament is grimy with grease’. The end result was a neighbourhood ‘in the possession of filth, often accompanied by squalor and wretchedness’.Footnote 61 Thus domestic cleanliness was in part a way to stave off anxiety about downward mobility, and it became a talisman for ensuring middle-class prosperity.

In 1874, Godwin – now with the actress Ellen Terry and the father of two children – leased a terrace house in one of Bloomsbury's ‘large squares’, and this time his interventions were more ambitious. In the larders, pantries, bathrooms and water-closets, he covered the walls with sanitary, glazed tiles and rendered the ceilings with parian cement, a plaster mixed with borax, often used for hospital walls in order to achieve a non-absorbent surface. In the kitchen, he installed a ventilating flue and altered the discharge for the scullery sink in order to lessen the smell of spring cabbage and broccoli.Footnote 62 Ruthlessly, he stripped ‘every fragment of paper, paint, &c’ off the walls, and also disposed of chandeliers, ‘huge dust-collectors as they were’.Footnote 63 As in his bachelor chambers, he designed furniture that fused economy and neatness, writing that

When I came to the furniture, I found that hardly anything could be bought ready-made that was at all suitable to the requirements of the case. I therefore set to work and designed a lot of furniture, and with a desire for economy, directed it to be made of deal, and to be ebonised. There were no mouldings, no ornamental metalwork, no carving. Such effect as I wanted I endeavoured to gain, as in economical building, by the mere grouping of solid and void.Footnote 64

Godwin avoided details such as mouldings or carving in his furniture, in order to obtain visual effects of simplicity and elegance but equally so as to avoid crevices where dust, grime and insects could collect. He called this ‘economy in cleaning’, an essential tactic for staving off ‘the disagreeable close atmosphere’ endemic to homes in congested urban centres.Footnote 65

In order to clarify further how Godwin translated these theories into practice, his famous ebonised sideboard of 1867–70, now one of the highlights of the Victoria and Albert Museum's design collection and an ‘icon’ of the Aesthetic Movement, will now be examined in detail (Fig. 7). At first glance, this rather severe credenza may seem to privilege purely formal interrelationships, embodying the ‘grouping of solid and void’, which Godwin described in the passage quoted above. Like an abstract sculpture, the sideboard is composed of carefully calibrated relationships of horizontal and vertical forms, which work in tandem with ‘negative space’ to create syncopated visual rhythms. On closer inspection, however, it becomes apparent that functional issues contribute to much of the design. The continuous horizontal surface, lacking any rails or wood trim as a border, is easy to wipe clean because of the way in which the two closed cabinets are lifted above the countertop: points of connection are few and minimal in cross section. The open shelves, moreover, allow for display of prized plate or large ceramics while the closed cabinets store and keep dust off of everyday serving ware. The embossed leather inserts at the four doors soften the sideboard's rectilinear outlines and act as impervious surfaces that can be wiped more easily than a fabric such as silk or linen.Footnote 66 They also provide a medium tonality between the ebonised mahogany planes and the silver-plated handles. Godwin was aware that black furniture could impart a lugubrious character to rooms, so the silver hardware and soft grey-stained leather assuage such an effect. In contrast to most sideboards of the era, moreover, the sideboard has no solid back that would create corners to entrap dust or crumbs. It is also less than six feet tall, so that the tops of the closed cabinets can be reached for dusting. The very lightness of the constituent wood framing also reveals the designer's concern with simplifying housekeeping, for the whole sideboard could be easily moved when the room needed to be dusted or swept. Even if left in place, it allowed for ease of room sweeping, for the lower shelves stand on thin legs about nine inches above the floor.

Fig. 7. E.W. Godwin, sideboard, c. 1867-70; made by William Watt & Co; ebonised mahogany, silver-plated fittings and embossed Japanese leather paper inserts (© Victoria and Albert Museum, CIRC.38:1 to 5–1953)

Ample open space below bottom rails or shelves is a feature of almost all of Godwin's sideboards, tables, and dressers. Indeed, one of his most emblematic lines of furniture – the hanging cabinet – took the idea of open space for room-sweeping to its almost limit by having it literally suspended above the floor. Godwin described one of his hanging bookcases manufactured by William Watt, as ‘the best and cheapest thing I ever designed’.Footnote 67 This bookcase has been identified by Susan Weber Soros (Fig. 8), and, like his better-known sideboard, it simultaneously a strikingly abstract composition and a functional piece of furniture is that responds to the daily necessities of domestic life.Footnote 68 Godwin's colleague Edis must have had such a design in mind when he wrote that ‘Hanging book-shelves with cupboards on each side for medicine bottles are invaluable in a bedroom’.Footnote 69 While Godwin described the bookcase as hanging in his own bedroom, he illustrated it in the Watt catalogue as placed in a dining room. Above the top shelf is a rail for the display of small pieces of china, which would act as decorative counterparts to the two cupboard doors below, elaborated with chrysanthemum motifs. Whether hung in a dining room or bedroom, however, the bookcase accords with William Morris's injunction that every room should have books in it.Footnote 70 It would have been particularly appropriate for a middle-class dwelling – like Godwin's designs for Bedford Park – without a library and where the dining room could serve such a dual purpose.Footnote 71

Fig. 8. E.W. Godwin, hanging bookcase, c. 1875; made by William Watt & Co; ebonised mahogany, stencilled decoration and silver hinges (© Sotheby's, London)

Such a simple work exemplifies Godwin's intentions regarding economical and functional furniture, which be describes as follows:

The scantling or substance of the framing and other parts of the furniture was reduced to as low a denomination as was compatible with soundness of construction. This seemed desirable for two reasons—firstly, for economy's sake in making, and secondly, for economy in cleaning. For by making all the furniture, the large pieces as well as the small, as light as they could well practically be, there was no particular effort required to move them either for the purposes of cleanliness or in the event of a change being desirable. Indeed, I found by experience that no man or extra servant was ever required, that I could with ease, single-handed, shift the whole of the furniture from one room into the next.Footnote 72

Thus, like Morris, Godwin thought that a room should not be crammed with too much moveable furniture, or ‘moveables’Footnote 73 but he differed some what from Morris in his emphasis on flexibility and adaptability.Footnote 74 The sideboard's two end leaves could be extended when needed, while the whole item could be picked up and moved if the owners desired to rearrange their room. In addition to ease of cleaning, Godwin's theories articulated a conception of dwelling in which adaptability was desirable, pointing to a penchant for restlessness and need for novelty. Godwin's own life veered close to the nomadic at times, as Juliet Kinchin has perceptively noted:

Godwin's lifestyle was certainly full of discontinuities and instability. As the rent checks bounced and the bailiffs arrived, he moved from one office to another, continuing the process of constantly re-creating his environment. Even when not bounded by economic necessity, he would constantly fiddle with the composition of his home in the light of his shifting perceptions … the practicalities of modern living meant travelling light, avoiding an accumulation of possessions …. This was expressed in the paring down of room contents and the lightweight design of the furniture.Footnote 75

Paring down was nowhere more needed than in dining rooms, which Godwin wrote about with gusto in ‘My House “in” London’. He condemned conventional English dining rooms as ‘always heavy, not to say gloomy’ retreats where massive furniture seemed to ‘groan under the weight of barons of beef’.Footnote 76 Cumbersome furniture and thick carpets, together with viscous, hard-to-clean wall-hangings and densely-leaded windows all created a funereal atmosphere. ‘I have attended a few funerals and I have had occasion to attend in a few conventional dining rooms during their non-festive intervals’, Godwin wrote, and of the two, ‘I prefer the funeral’.Footnote 77 Worse than dingy in appearance, such rooms exuded unhealthy odours, as the furnishings created reservoirs for dust and insalubrious grime:

Nothing can be more offensive than flock papers and woollen hangings, the usual surroundings of an Englishman's dining table. Who has not experienced in such rooms many a stuffy stale reminder of an exhausted feast? When the men smoke after dinner – and where do they not? – there is the additional advantage of breakfasting in an atmosphere that derives a flavour of stale tobacco from the stores laid up overnight in wallpaper and curtain.Footnote 78

Godwin instead strove for a lightness appropriate to modern manners, which are becoming increasingly ‘brightly effervescent’. Furniture for the contemporary dining room, he wrote, ‘should be light, and the architecture and decorations in accord with it should be cheerful and bright’.Footnote 79 He painted the walls of his own dining room a ‘vivid blue’ that ‘lights well’ by either candlelight or daylight, and which contrasted with the ‘sickly green’ and ‘melancholic’ madder tones of mid-century.Footnote 80 He had grown to abhor the tertiary greens then in favour since they seemed to absorb a room's illumination: ‘dull sad greens on walls or floors’ was his summary of the prevailing fashion.Footnote 81 He described how, when redecorating his chambers in 1872, he consulted an ‘outspoken doctor of the pure air and fresh water school’ who warned him of the doleful mood induced by these ‘dirt-mixed, light-absorbing greens’.Footnote 82 The doctor compared their deleterious effects to wallpapers in green tints compounded with arsenic. Such arsenical wallpapers were an especial concern of sanitarians, and their journal, The Sanitary Record, featured numerous case students of inhabitants poisoned by their wallpaper.Footnote 83

To complement his blue-painted dining room, Godwin hung simple linen curtains with embroidered borders in blue and yellow. The result was a ‘joyous’ modern room, appropriate to a culture of sweetness and light, which he and his fellow aesthetes sought as part of an idealistic and optimistic social project. He wrote:

My wall[s], therefore, instead of being dull, lifeless, [and] depressing as even painted walls too often are when the figures are painted flat with strong outlines, are on the contrary always cheerful and sometimes even lively. The floor is covered with Indian matting (the plain yellow colour) .… No words, however, can give an adequate notion of the joyous kind of light in this room, whether illuminated by sun or duplex lamp or candle. Joyous it is, without being in any sense disturbing, and this, I take it, should be the character of our dining-rooms if we wish to complete the light and improved menu of the present day with appropriate surroundings.Footnote 84

The other room most in need of simplification was the bedroom. Godwin's furniture and interior schemes for bedrooms were among his most austere designs (Fig. 9), as he acknowledged when he wrote that ‘My bedrooms are what some would undoubtedly call bare and cheerless’.Footnote 85 His warnings against dust traps reached their apogee when he cautioned that ‘if only we could see the depth of fluff and filth concealed within two yards of our mouths we should prefer [sleeping in] a doorstep’.Footnote 86 In order to create an airy and hygienic room, he specified brass or iron bedsteads ‘without tester or curtain’, simple wooden dressing tables and washstands left unstained so that they could be washed, and small rugs on plain wood floors. He recommended, furthermore, the room ‘should be scrubbed once a week, and in hot weather twice’.Footnote 87 To facilitate this cleaning regimen, the walls were not papered but painted with distemper, an early form of whitewash. Chairs with cane seats imparted a ‘clean golden look’ to the room, acting as mood enhancers. ‘The consequence of all this is that the room is never stuffy’, he declared, ‘thus the room, though light, is full of repose’.Footnote 88

Fig. 9. E.W. Godwin, furniture designs for a bedroom, c. 1876; from a sketchbook containing designs for furniture and interiors as well as drawings of architecture; pencil, pen and ink, water-colour and gouache (© Victoria and Albert Museum, E.233–1963)

Healthy bedrooms were topical in the 1870s, and were discussed in decorating manuals such as Lady Barker's The Bedroom and Boudoir, which reveal the wide diffusion of sanitary concerns. In his preface to this book, W.J. Loftie noted that the reader will find ‘many hints with regard to the sanitary as well as the ornamental treatment of the bedroom’.Footnote 89 For Barker, a bedroom's primary attributes should be ‘fresh air, spotless cleanliness, and stately and harmonious beauty’.Footnote 90 Fresh air was foremost among her prescriptions, whether achieved through opening windows, leaving the room's door ajar, loosening bricks in the exterior wall (!), or using the chimney flue as a ventilating stack, since ‘by night every dwelling-house gives out bad air, like a slaughter-house’.Footnote 91 After opening her volume with such arresting comments, however, including an allusion to the threat of visits by sanitary inspectors, she quickly turns to descriptions of bedrooms as ‘dear delightful dens’. Her ideal is ‘a pretty bowery bedroom, half dressing room, half boudoir’,Footnote 92 and she counsels against iron and brass bedsteads and ‘too great austerity’.Footnote 93 Godwin's stringently hygienic designs for bedrooms must have seemed to Lady Barker more fitting for sick rooms (about which she includes a chapter) than for the charming boudoirs she extolls.Footnote 94

CURING URBAN MELANCHOLY

Where Barker and Godwin concurred, however, was in their fixation on rooms as determinants of mood and well-being. The aesthetic interior became for Godwin an instrument for inducing well-being, as he looked to decoration as a means of promoting psychological health. He repeatedly anathematised melancholy, depression and sadness as the products of a bad environment. In his view, life in the modern metropolis induced stress but this could be alleviated through a well-designed home. He referred to ‘these high-pressure, nervous times’ where ‘harsh discordant street cries’ in a city ‘under cold murky skies’ were daily facts of life.Footnote 95 London's weather itself seemed to exert an oppressive psychological force, and Godwin described how

The large majority of our days out-of-doors are grey and cold, and it is these we should think of when we come to decorate and furnish, so as to get some relief indoors from their chilling, depressing influence.Footnote 96

Consequently, Godwin was careful to specify the solar orientation of each room, noting how daylight can affect both decorating schemes and the inhabitants’ moods. He thus adopted a psychologically instrumentalist view of the domestic interior, believing that wall colours, curtain materials and the arrangement of furniture could rejuvenate an inhabitant's temperament. In fact, his own residences were laboratories in which to test his theories of design as a way to improve mood and well-being. Such a deterministic outlook and interventionist approach also reflected the mentalité of the sanitary reformers. Chadwick's Report had galvanised the government to intervene in society in an activist way that contrasted vividly with the laissez-faire policies characteristic of the early nineteenth century in Britain.Footnote 97 The reform campaigns of the sanitarians and the dispensers of decorating advice thus converged in targeting the environment as both a medium of influence and an agent of change.

In his self-selected, delimited purview, Godwin campaigned for sanitary and aesthetic intervention in the urban house. ‘The education of the senses’ became his rallying cry as he ‘set to work at decorating and furnishing’.Footnote 98 Divulging an ocularcentric bias of his outlook, he underlined the visual determinants of behaviour when he wrote that

[A] room has a character that may influence for good or bad the many who enter it, especially the very young. The influence of things seen is greater on some people than the influence of things heard. With myself I know that the memory of the eye's experiences is far and away beyond that of the ear, and I do not for a moment imagine that I stand alone in this particular.Footnote 99

In accordance with this view, the nursery became, for Godwin, an area of special concern. ‘The nursery is the first school in this life, and the eyes of its little inmates are amongst the first leading channels of unconscious instruction or experience’, he wrote, in perhaps his most direct statement on the psychological effect of the domestic interior.Footnote 100 He found very few mass-produced toys good enough for children and recommended instead ‘a few well-selected Japanese fans’ as ornaments in rooms designed with ‘a pleasing grace about everything’.Footnote 101 Nursery furniture should be painted white or made of natural wicker, and fashioned with rounded corners for ease of cleaning and for safety.Footnote 102 As a veritable classroom in a child's aesthetic education, the nursery should be designed, he insisted, ‘not merely for the dawn, but for the sunrise of intellect’.Footnote 103

Godwin's sympathetic insights into childhood were shared by like-minded figures of the period. The artists Walter Crane and Kate Greenaway, for example, created graphic work that seemed to understand childhood as a special psychological and emotional preserve. In 1888, Oscar Wilde published a volume of short fiction, The Happy Prince and Other Tales, which explored the complexities of filial and parental relationships.Footnote 104 Wilde's son Vyvyan has described the spirit of play that animated Wilde's relationship with his two children and the strong bond of sympathy the playwright promoted within the ludic space of childhood.Footnote 105 The sensitivity and seriousness which Wilde and aesthetes such as Godwin, Crane and Greenaway brought to childhood were, however, unusual in Victorian Britain.Footnote 106 It was one of the most progressive aspects of the Aesthetic Movement and exemplifies the optimism at the heart of their project, and central as well to the overlapping Queen Anne revival.Footnote 107 For an aesthete such as Godwin, it was a motivating force. His calls for lightness, delicacy and refinement in design were all part of a clear-sighted, adversarial standpoint that opposed the commercial, stultifying and anti-artistic pressures of nineteenth-century mercantile society.Footnote 108

Godwin made his position very clear in an article published in 1878 entitled ‘National Art’, in which he argued that sanitary reform needed to be complemented by a reform of the nation's artistic sensibility. ‘An improved state of general health is certainly possible and assuredly desirable’, he wrote, and ‘happily, science is working to improve our general health’.Footnote 109 But it was left to Godwin – joined, presumably, by artistic colleagues such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) – to complete the task by revivifying society's appreciation of art an ambition that can be traced to Godwin's youthful reading of John Ruskin (1819-1900). ‘Hygienic development means more life, and this must eventuate in art’, Godwin averred.Footnote 110 This short sentence encapsulates Godwin's credo – his linking of physical health with aesthetic sensitivity. This thinking may be summarised as follows: as modern science improved the physical aspects of life, more time and opportunities would become available for the higher pursuits of art or intellectual labour – what Godwin called ‘the high delights of art’.Footnote 111 Sanitary reform as an end in itself did not interest Godwin unless it figured in a hierarchical system of values that placed art at the apogee. ‘Say what we will’, he wrote, ‘art is the ultimate polish of man’.Footnote 112 Hygiene, by contrast, although a vital precursor to aesthetic experience, remained in the realm of ‘the commoner functions of life’.Footnote 113

DRESS REFORM AND THE INTERNATIONAL HEALTH EXHIBITION

Before concluding, I would like to return to the larger social context I alluded to earlier. One area of hygiene with wider public implications that preoccupied Godwin was the topic of dress reform. In 1884, the International Health Exhibition installed a display in the Albert Hall on the theme of dress in relationship to hygiene, covering selected periods in English history. Life-sized models made by Madame Tussaud's were dressed in examples of historical costume as part of a comparative study of civilian dress, arranged chronologically.Footnote 114 Attracting more than four million visitors, the fair was intended to chart progress in the study of health; and it became known as the ‘Healtheries’.Footnote 115 Edwin Chadwick was invited to the fair's opening as a guest of the exhibition's royal sponsors.Footnote 116

A list of conference-related publications shows how topical hygiene had become, as almost every aspect of Victorian life was now subject to health-consciousness: Health in the Village by Henry W. Acland; Healthy Nurseries and Bedrooms Including the Lying-In Room by Mrs. Gladstone; Healthy and Unhealthy Houses in Town and Country by W. Eassie; Healthy Schools by Charles E. Paget; Health in the Workshop by James B. Lakeman; Cleansing Streets and Ways in the Metropolis by William Booth Scott; Ventilation, Warming, and Lighting for Domestic Use by Captain Douglas Galton; and London Water Supply by Colonel Francis Bolton. All of these were published for the fair by William Clowes and Sons, and most were sold for a shilling each.Footnote 117 William Morris lectured on textiles while the architect Robert Edis presented a talk entitled ‘Healthy Furniture’, which was largely a summary of points Godwin had been making over the past decade.Footnote 118 In her comments on healthy nurseries, Catherine Gladstone, the wife of the prime minister, favourably mentioned Godwin's earlier writings on the topic.Footnote 119 Godwin himself gave a public lecture at exhibition's opening, later published as a ninety-page illustrated pamphlet entitled Dress and Its Relationship to Health and Climate.Footnote 120

Godwin's argument rests on a comparison between the hygienic home and the healthily-clad body:

The history of dress is curiously parallel with that of architecture; indeed, we might almost say that to dress rightly, and build rightly, and speak rightly, are the three great primary arts…. To build architecturally, we must have not merely proper materials and sound construction, and pleasant balancing of light and shade; but the ornament should be good in itself and well-adjusted, while the heating and ventilation, among other sanitary items, should be carefully considered. To build a dress or costume demands just the same kind of thought; and where the heating and ventilation are neglected we may be quite sure that we shall suffer.Footnote 121

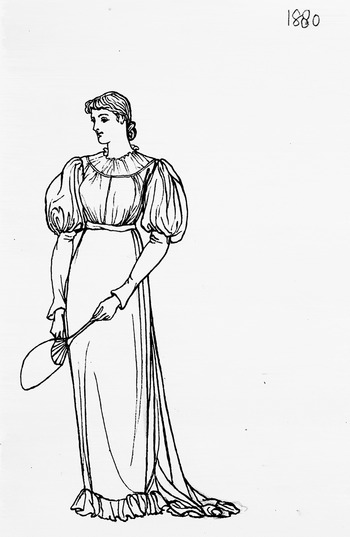

In concert with other dress reformers, Godwin sought to abolish tightly-laced corsets and skirts that hampered women's movement.Footnote 122 For examples of clothing that could drape women's bodies in an artistic yet healthful way, reformers looked to the Greek chiton and the medieval tunic and jupon,Footnote 123 although fretting over their relevance to the climate and culture of nineteenth-century Britain (Fig. 10). Godwin, who was named advisor on dress at Liberty's department store also in 1884, suggested that women should wear Grecian-inspired apparel over the sanitary woollen underwear advocated by the physiologist Dr. Gustave Jaeger.Footnote 124 Oscar Wilde supported Godwin's suggestion in a letter to the Pall Mall Gazette.Footnote 125 Japanese kimonos were also admired, and Godwin had encouraged his mistress Ellen Terry and their daughter Edy to wear them at home,Footnote 126 apparently evincing no anxieties over cultural appropriation as would be the case today. Regarding menswear, he was much less sanguine, asking ‘how much longer the chimney-pot hat, the respectable frock coat, and the baggy trousers are to enslave one half of the civilised world?’ As with his critique of ‘melancholy’ colours in interior decorating, he condemned the ‘gloomy monotony’ of broadcloth used in ‘bag-like’ men's suits; he execrated frock-coats with trousers as ‘abominations’.Footnote 127 As an alternative, he found much to admire in a simple, well-fitted Norfolk jacket, an appreciation that predated by twenty years the Viennese architect Adolf Loos's writings on men's fashion.Footnote 128 For the anglophile Loos, the clean lines and functional tailoring of the Norfolk jacket exemplified England's status as cynosure of modernity.Footnote 129 Needless to say, Loos also admired British plumbing.Footnote 130

Fig. 10. E.W. Godwin, drawing of a woman in Aesthetic dress, 1880; Pencil and ink (© Victoria and Albert Museum, Theatre and Performance Archives, S.190–1998)

CONCLUSION

As Annmarie Adams has noted, dress reform was the obverse of measures to improve domestic hygiene. The concept of a healthy body in a healthy home was at the heart of the Domestic Sanitation Movement that prevailed from 1870 to 1914.Footnote 131 Godwin's designs of the 1860s and his writings of the 1870s established him as a forerunner among designers who embraced the discourse on hygiene set in motion by reformers such as Chadwick. His Ruskin-inspired efforts to infuse life with art were intended as an affirmative enhancement of well-being, in a humanistic sense, deriving from a hierarchical set of values with art as the apogee of human endeavour. If such a confluence of concerns may seem to architectural historians to be an unstable compound, historians of the sanitary reform movement have grown accustomed to recognising the alignment of physical, moral, and even metaphysical health in Victorian physiological thinking.Footnote 132

In a career that encompassed architecture and interior decoration, journalism and criticism, theatrical staging and costume design, Godwin campaigned to inject modern life with aesthetic awareness, ‘to have art present with a growing, developing, living, joyous reality’. His furniture demonstrated how art and sanitation could be brought to bear on the everyday necessities of domestic life. While he participated in a broad discourse on hygiene that characterised the Victorian era, his intermingling of the aesthetic and the salubrious sounded a personal note that reinforced the status of the architect as arbiter of the exemplary urban dwelling. His thorough-going preoccupation with cleanliness, a hygienic home and psychological respite places him firmly among the sanitary reformers, but his furniture shows how assiduously he could translate their concerns into functioning components of a healthy environment.