In 1571 the English parliament declared that the bringing of any tokens ‘by the name of Agnus Dei’ into the realm, ‘or any crosses, pictures, beads or suchlike … things from the bishop or see of Rome, or from any persons or persons authorised or claiming authority by or from the said bishop or see of Rome to consecrate or hallow the same’, would henceforth incur the penalties of the statute of praemunire, including imprisonment and the loss of one’s property. Those caught wearing or using any such items would likewise suffer the penalties of the statute.Footnote 1 The outlawing of these objects was one part of legislation that considerably extended the treason laws and inhibited the practice of Catholicism in England. In addition to prohibiting the use and importation of sacred objects employed in Roman Catholic devotion, the statute declared that anyone who imported, used, or attempted to publish any bulls from Rome would be charged with treason, and their abettors would be charged with praemunire.Footnote 2

In spite of the new laws, Catholic communities in England continued to use blessed objects including rosaries, beads, blessed grains, and agni dei (the plural of agnus dei, wax tablets blessed by the pope) at great personal risk. Because it was consecrated by the pope, the agnus dei was a precious devotional object amongst Catholics in early modern Europe; but in England, it also assumed unusual political connotations after 1570 because of growing conflict between Elizabeth I and the papacy.Footnote 3 Despite the formidable punishments they faced, English Catholics and priests in the English missions continued to keep and smuggle in agni dei after 1570, and they remained popular well into the seventeenth century.

Much of the scholarship on the materiality of Catholic devotions in post-Reformation England has focused on the cult of relics and the circulation of texts.Footnote 4 As Alexandra Walsham has observed, the use of blessed objects and devotional books presented an alternative means of accessing the sacred, an especially important alternative for Catholics in England who could not always directly acquire the benefits of the sacraments.Footnote 5 Anne Dillon has made similar observations about the use of the rosary in English Catholicism and the formation of confraternities devoted to it in the seventeenth century.Footnote 6 Ironically, the severe curtailments which the new treason laws placed on access to the sacraments, and to priests who could administer them, may have increased the community’s demand for the very sacramentals the government also hoped to eradicate.

At the same time, from the mid-1570s seminary priests trained in the English colleges in Europe, and later members of the Society of Jesus, began returning to England to minister to Catholics, facilitating the revitalisation of the faith. These priests played a vital role in the circulation and distribution of devotional objects as part of these processes. Recent scholarship on the missions to England has produced fruitful debates about how missionary priests negotiated the difficult political and spiritual dilemmas placed upon them by the Elizabethan and Stuart regimes, and how they assisted the laity in navigating these dilemmas.Footnote 7 Yet their role in the circulation of prohibited devotional objects, and the political significance of participating in this circulation, has received less attention.Footnote 8 For those who returned to, or newly embraced, the Catholic faith after 1570, sacred objects could act as material aids for devotional practices which may have been new to them, but the objects also became potent symbols of resistance to the government and the established Protestant English Church.Footnote 9

This article will assess the agnus dei in Catholic devotion and politics in early modern England, considering its uses in pre- and post-Reformation devotion, its role in Catholic missions to England in the late sixteenth century, and the particular political significance it assumed during the reign of Elizabeth I. It will examine how the possession of an agnus dei acted not only as a tool of personal faith, but also as a symbol of defiance against the Elizabethan regime and an acknowledgement of the supremacy of papal authority.

The agnus dei in late medieval and early modern religious culture: uses and survival

The agnus dei was a popular devotional aid in pre-Reformation England and Europe, and had been in use from at least the eleventh century.Footnote 10 The agnus dei belonged to a special class of sacred objects called sacramentals: blessed objects which could exercise an effect over their possessor analogous to that of receiving the sacraments. Robert Scribner has described the widespread popularity of sacramentals in medieval and post-Reformation Europe as a means of gaining regular access to the sacred in daily life.Footnote 11 Unlike the sacraments, which the institutional church typically administered and controlled, the laity could use sacramental objects as they saw fit.Footnote 12 The agnus dei, however, occupied a special place amongst the sacramentals as an object consecrated by the pope. Its creation and distribution were subject to regulations that other objects did not receive.

Agni dei were conventionally made in the pontifical apothecary and consecrated by the pope during Holy Week in a special ceremony witnessed and assisted by the cardinals.Footnote 13 The ceremony was conducted in the first year of a pope’s election and once every seven years thereafter during his pontificate. Crafted from the wax of paschal candles, chrism oil, and holy water, the agni dei were stamped with the image of the Lamb of God on one side and the image of a saint or the name and arms of the consecrating pope on the other. They could be worn as pendants or preserved as devotional objects. The agnus dei was believed to possess many protective powers, including defence from storms, pestilence, fires, and floods, as well as the dangers of childbirth.Footnote 14

Figure 1 Bartolomeo Faleti, Pius V Consecrating the Agnus Dei, engraving on paper, 1567, British Museum, London, li.5.107. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Once consecrated the papacy typically distributed agni dei as gifts to cardinals, ambassadors, and other important figures in Rome, as well as to rulers throughout Europe. Following the initial distribution of the sacramentals, recipients might bestow agni dei upon other friends and relatives, or even share them with a wider social circle or community; in theory, they could not be bought and sold.Footnote 15 Because the wax medallions were fragile, it was also common to break an agnus dei into smaller pieces to be shared amongst the faithful, and carried in cases for protection.Footnote 16 Consequently, relatively few examples of agni dei from before the Reformation have survived intact, but many of the cases that were used to protect them have. Figure 2 shows an Italian example of a case from the fifteenth century, which is now held at the British Museum.

Figure 2 Agnus Dei Case, Italy, 15th Century, 1.6 cm x 1.6 cm, British Museum, London, 1902,0527.26. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

In England few agni dei have survived from before the eighteenth century, partly due to the fragility of the materials with which they were made, and partly because of the legal restrictions placed upon them in the late sixteenth century. A sixteenth-century agnus dei which was discovered at Lyford Grange in 1959, where the Jesuit Edmund Campion was captured in 1581, is now kept at Campion Hall in Oxford. This agnus dei, shown in Figure 3, bears the arms of Pope Gregory XIII, the pontiff who blessed it, and is thought to have belonged to Campion himself.Footnote 17

Figure 3 Lyford Grange Agnus Dei, 17 cm x 13.7 cm. By Courtesy of the Master and Community of Campion Hall, Oxford.

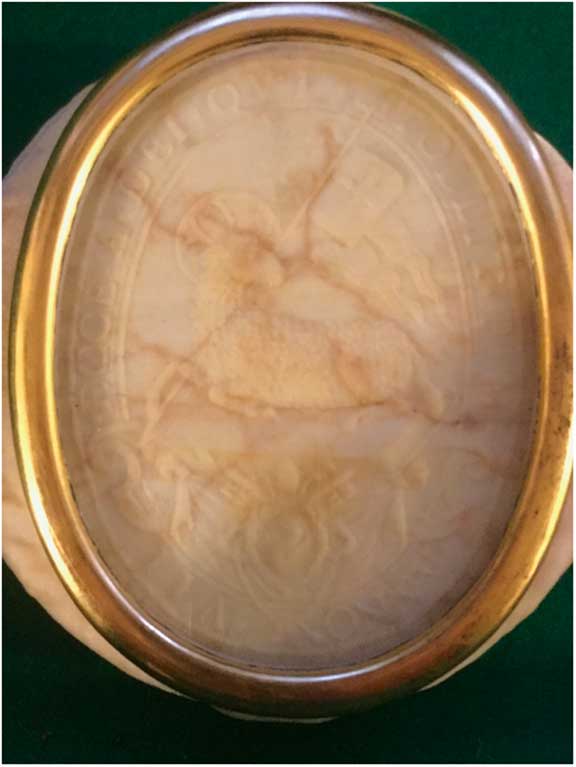

Stonyhurst College in Lancashire has several agni dei in its collections which were consecrated in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (see Figures 4 and 5), along with one known to be from the seventeenth century. This particular agnus dei (see Figure 6) is from the collections of the English College formerly at St Omer, and is enclosed in the back of a reliquary case. The front of the case contains a miniature figure of the Blessed Virgin Mary holding the infant Jesus, which is thought to be carved from the wood of a tree that once stood in the college courtyard at St Omer.

Figure 4 Agnus Dei fragments, ca. 19th century. By permission of the Governors of Stonyhurst College, Lancashire.

Figure 5.1 Agnus Dei consecrated by Pope Leo XIII, recto, 7 cmx5 cm. By permission of the Governors of Stonyhurst College, Lancashire.

Figure 5.2 Agnus Dei consecrated by Pope Leo XIII, verso. Image of St Joseph and the Infant Jesus. By permission of the Governors of Stonyhurst College, Lancashire.

Figure 6.1 Agnus Dei enclosed in a reliquary, 17th century, 7.5 cm x 5 cm. Around the disc are the names of English Jesuits, including Edmund Campion, Robert Southwell, Henry Garnet, Henry Walpole, and John Gerard. By permission of the Governors of Stonyhurst College, Lancashire.

The agni dei shown above vary considerably in size. The medieval Italian example is circular in shape and approximately 1.6 cm in diameter, while the nineteenth-century agnus dei is oblong and 7 cm in length.Footnote 18 The Lyford Grange agnus dei is considerably larger, with a length of 17 cm (See Figure 4). The St. Omer agnus dei, on the other hand, is oblong and approximately 2.5 cm in length. It also shows signs of being altered to fit into the reliquary case amongst papers that list the names of English Jesuits.

Despite the inconsistent survival of agni dei, other surviving evidence points to the part they played in pre-Reformation devotional culture. Probate records, for instance, indicate the significance of the agnus dei as a bequest to friends and family in England, especially for women.Footnote 19 Constance Despenser received an agnus dei encased in gold from her husband upon his death in 1400.Footnote 20 Similarly, the will drawn up by Henry, Lord Scrope in 1415 dictated that an agnus dei be left to his kinswoman, Mathilda Skidmore, after he died.Footnote 21 In 1524 William Peerson, an alderman and draper of Lincoln, bequeathed an agnus dei and a pair of red coral beads to his daughter Elizabeth.Footnote 22 The agnus dei was particularly prized for the protection it supposedly accorded to mothers and children, and it is likely these associations that made it a conventional bequest for women.Footnote 23 The papacy frequently sent boxes of agni dei as gifts to queens regnant and consort who were expecting or had just delivered children.Footnote 24

Priests and religious houses also kept agni dei for personal and communal use. An inventory of the possessions of Roger Kirkby, the vicar of Gainsford in County Durham from 1401 to 1412, included an agnus dei and a pair of blessed beads.Footnote 25 William Thornburgh, priest and master of the College of St Mary-On-The-Sea, provided an agnus dei for the college chapel in his will in 1525, which was hung around the neck of a statue of the Blessed Virgin along with ‘certain relics’.Footnote 26 The abbey of Holme Cultram also kept an agnus dei pendant to assist women in childbirth before its dissolution in 1536.Footnote 27 The agnus dei was therefore a precious devotional object in pre-Reformation England, shared amongst family members and neighbours to ward off the many dangers posed by everyday life in this period. Its expansive protective powers made it an appealing gift for women, children, and men at multiple levels of society.Footnote 28

The agnus dei in post-Reformation England

In the aftermath of the Reformation and Henry VIII’s break with Rome, sacred objects such as relics and sacramentals were frowned upon by evangelical reformers in the new ecclesiastical establishment. Alexandra Walsham has examined how polemical attacks on Catholic devotional objects dismissed them as ‘trash’ and ‘trumpery’ in post-Reformation England, and suggested that this language has overshadowed the study of the material culture of Catholicism in early modern Britain.Footnote 29 Although evangelical reformers attacked the sacred materials of Catholicism as idolatrous, and many of these items were destroyed in the iconoclastic movements of the 1530s and 1540s, they were never formally outlawed by any act of parliament under either Henry VIII or Edward VI. Consequently, we still see traces of the sacramentals being used and passed between family members in this period. Roger Bellingham’s will, proved at York in 1541, for instance, left instructions for an agnus dei and a ring to be left to his daughter, Elizabeth Fitzthomas.Footnote 30 After the restoration of Catholicism under Mary I and the reparation of relations with Rome, sacramentals were again encouraged as devotional aids. In 1556 Sir Edward Carne, one of the English ambassadors in Rome, sent a box of agni dei to Queen Mary from Pope Paul IV, along with a small Italian book describing the ceremonies used in their production.Footnote 31 However, with the accession of Elizabeth I and the settlement of religion in 1559, which re-established an official, Protestant English Church, sacramentals and other Catholic devotional objects once again became targets of suspicion and ridicule, as the new, reformed establishment set about dismantling the Catholicism restored under Mary I.

The latest alteration of official worship brought with it the fresh destruction of altars, relics, vestments, plate, and other precious materials that had been replaced during Mary’s reign.Footnote 32 Years of religious rupture had also taken their toll: the remains of sacred sites and shrines destroyed in the 1530s and 1540s were left to decay by the new Protestant regime, which cut ties with the papacy. In this environment, as access to the Mass, sacraments, and holy sites became increasingly limited, English Catholics found different ways of maintaining spiritual connections with the Roman Church.Footnote 33 Anything that helped to uphold a physical or material link with the Church in Rome, such as a relic from the city’s catacombs, or a sacramental blessed by the pope like the agnus dei, became critical to the preservation of the faith.Footnote 34 While portable devotional objects like relics and sacramentals were especially important to the repressive conditions in which English Catholics worshipped, they were highly prized throughout early modern Europe, serving as expressions of a community’s connection to Rome and the early Christian Church.Footnote 35

Despite the change in established religion, parliament did not outlaw the importation and use of agni dei until 1571. The ban on agni dei was added to legislation that effectively equated several practices of Roman Catholicism, including the use of papal bulls, indulgences, and other consecrated materials, with treason. The expansion of treasonable offences to include the importation and use of hallowed objects was a direct response to the excommunication of Elizabeth I by Pope Pius V in 1570, and to the religious tensions which had precipitated the censure. The excommunication, pronounced in the bull Regnans in Excelsis, also declared that Elizabeth was deprived of the right to rule her kingdom, and that anyone who continued to obey her laws (civil or religious) or show her allegiance would likewise be excommunicated.Footnote 36 The pope published the excommunication in response to the Northern Rebellion of 1569, which had been led by the earls of Northumberland and Westmoreland. Surviving records indicate that over six thousand people joined the rebellion, and prominent amongst the rebels’ grievances was discontent with the ways in which the Protestant religious settlement was being enforced in the northern counties. During the rebellion, the Mass was openly celebrated in Durham and married clerics were forcibly ejected from their livings in Yorkshire.Footnote 37 The papal excommunication of Elizabeth, issued in the wake of this resistance, provoked substantial concerns in the queen’s government. For the queen and her ministers, the excommunication called into question the loyalties of everyone in England who considered themselves Catholic, because the papacy now expected them to resist the queen if they wished to avoid excommunication themselves.Footnote 38 The legislation passed by parliament in response to the papal censure of Elizabeth further complicated the situation of English Catholics. Those who defied the new laws risked prosecution for treason, while those who ignored the pope’s demands risked the spiritual dangers of excommunication.

In post-Reformation England, the agnus dei therefore acquired new political connotations following the papal excommunication of Elizabeth I and the passage of laws that banned many sacred Catholic devotional materials in 1571. The acknowledgment of papal supremacy implicit in the possession of an agnus dei was one of the principal reasons it was outlawed as a treasonous object. As a sacramental that derived its powers directly from the pope, the agnus dei implicitly signified its owner’s belief in the papacy’s spiritual and temporal supremacy. In theory, Catholics who had not reconciled themselves to the Roman Church and acknowledged this supremacy could not benefit from sacramentals like the agnus dei.

As Lucy Underwood has noted, reconciliation had multiple meanings in English Catholicism. It could signify the bringing in of baptised persons, or the return of those who had formerly fallen into heresy, into membership of the Roman Catholic Church. Reconciliation could also refer to the absolution of one’s sins as part of the sacrament of penance. As such, reconciliation was closely connected with processes of conversion to the Catholic faith, which involved receiving absolution from the sins of heresy.Footnote 39 Conversion could also occur internally within the Catholic faith, when an individual achieved a more perfect spiritual state.Footnote 40 In the English context, if one wished to reap the spiritual benefits of an agnus dei, this meant that the its possessor needed to have completely embraced the Roman Catholic faith and the beliefs in papal supremacy that came with it. The possession of such a sacramental could therefore also indicate that its owner may have undergone reconciliation in some form.

Reconciliation and conversion were central to the missions of Catholic priests who were sent into England to sustain the faith, and the circulation and distribution of sacramentals like the agnus dei became connected with these processes. Seminary priests smuggled these objects into England from the beginning of the mission in 1574, and the Jesuits began bringing sacramentals with them from the mid-1580s, distributing them to reconciled Catholics and to others they hoped to convert. Fearing the effects of the missions on the allegiances of English Catholics, in 1581 parliament added reconciliation by a priest to the list of treasonable offences, further entangling the practices of Catholicism with questions of fealty to the crown and kingdom.Footnote 41 In order to enforce this new law for the purposes of identifying and, subsequently, prosecuting Catholics, Elizabethan authorities increasingly pointed to the possession of blessed objects such as rosaries and agni dei as evidence of someone’s reconciliation.Footnote 42 As precious a spiritual object as the agnus dei may have been, it could be equally as dangerous because of what it implied about its owner’s beliefs concerning the queen’s legitimacy as a ruler. From the Elizabethan government’s perspective, the possession of sacred objects like the agnus dei signalled not only a change of religion, but also a change in loyalty and an inclination to resist the crown, all rooted in the implications of the papal excommunication of Elizabeth I.Footnote 43

Notes and observations of the agnus dei proliferate in English official records after 1570. It is difficult to tell if this reflects a renewed interest in the sacramentals amongst English Catholics, and an increase in attempts to circulate them, or if this phenomenon simply reflects an increase in attention paid to them because of the new laws that banned them. While the agnus dei functioned as a devotional and protective aid, it was not essential to the practice of Roman Catholicism in the way that the Mass and the sacraments were.Footnote 44 Despite this and the statute prohibiting them, agni dei remained popular with English Catholics throughout the rest of Elizabeth’s reign. Seeing the continued demand for the sacramentals, missionary priests smuggled them into England and distributed them to the families they visited, despite the increased dangers of their being recognised and captured by the Elizabethan authorities. This raises questions about the degrees to which Catholics were willing to defy the queen’s government after 1570, and whether the missionaries played any role in persuading Catholics into more politically charged expressions of dissent. Where it is possible to trace those who kept and distributed agni dei in England, these practices may also illuminate processes of reconciliation and conversion at work within Catholic communities. It may be possible to discern whether these individuals would have been receptive to papal calls for resistance to the queen, and the ways in which English Catholics interpreted these demands for resistance.

The agnus dei in Catholic missions after 1571

The laws against the importation and use of agni dei were strictly enforced for the rest of Elizabeth’s reign, and her ministers kept watch over those who circulated them along with other sacramentals. In 1572 government agents intercepted a letter written by Thomas Bailey, an English exile living in Louvain, in which he expressed a desire to send to his friend John Swinburn in England a number of books, beads, and agni dei. Bailey feared that Swinburn would not be allowed to keep them and that they would fall into the wrong hands.Footnote 45 In July of the same year Henry, Lord Hunsdon wrote to William Cecil, Lord Burghley from Berwick to report that he had arrested William Carr, a priest who served the exiled countess of Northumberland, trying to make his way into England from Scotland with ‘a number of letters, beads, agnus deis, friars girdles for women in labour and such other’ items.Footnote 46 Although no statement of Carr’s intentions appeared in the report, it is likely that he intended to distribute the items amongst the English Catholics that he met during his travels. Many of the people caught smuggling and distributing the agni dei in England were in fact seminary priests, and the practice of carrying the sacramentals for distribution in England appears to have escalated from the late 1570s. The bishop of London arrested a priest named Jonas Meredith in March 1577 after finding him with ‘divers Agnus dei’ and beads. Meredith had already distributed several of these items in the city and in Lancashire, where he had previously ministered.Footnote 47 Cuthbert Mayne, who converted to Catholicism after Elizabeth I’s excommunication and trained for the priesthood at the English College in Douai, was carrying at least one when he was arrested in Cornwall in August 1577. At his trial Mayne was accused of giving an agnus dei to his patron, Francis Tregian, and another to a group of eleven people in 1576.Footnote 48 Thomas Wiles, another priest in London, was convicted of praemunire for having an agnus dei in March 1578.Footnote 49 Similarly, two priests named Henry Clark and Nicholas Bawdyn were arrested in Plymouth in Devon at the end of the year with ‘an Agnus Dei, popish books, and other papistical relics, with certain letters’ which they had intended to distribute in England.Footnote 50

The increased efforts to smuggle agni dei into England coincide approximately with the first year of Gregory XIII’s pontificate (1572), when the Vatican would have produced and consecrated agni dei according to the convention for new popes, and with the beginning of efforts to send seminary priests into England to minister to Catholics. Cases in the casuistry manuals for priests point to their importance in distributing the wax pendants. The manual written by William Allen and Robert Persons encouraged priests to bring agni dei and other blessed objects into England because ‘pious things were not to be neglected because of danger’.Footnote 51 While they instructed the priests only to give agni dei to those who wanted them, Allen and Persons also suggested that such objects could be given to those in schism with the church, as long as there was no danger that they would abuse them.Footnote 52 This points to the potential of the agnus dei as a tool of evangelisation, by which priests could encourage people to embrace or return to the Catholic faith. The use of sacred materials in this manner was common in other parts of early modern Europe. Howard Louthan’s work on the re-Catholicisation of Bohemia after the Thirty Years’ War illustrates how ecclesiastical authorities and missionaries employed a range of measures to encourage people to return to the faith, including public rituals, works of art, and the encouragement of the cult of saints through the translation of relics.Footnote 53 Similarly, Trevor Johnson’s assessment of the religious transformation of the Upper Palatinate in the same period demonstrates the significance of a sacred economy of images, sacraments, and sacramental objects to the success of Catholic reforms in the region.Footnote 54

While seminary priests working in England were encouraged to bring sacred objects like the agnus dei to those to whom they ministered, Jesuits received mixed advice on the use of sacred objects in their mission to England after the enterprise was approved in 1580. The instructions given to Edmund Campion and Robert Persons, the first Jesuits in the mission, by the general of their Society in 1580 forbade them from bringing any devotional articles which had been proscribed under the treason laws, including agni dei and blessed grains of incense, and instructed the Jesuits not to carry or wear them for personal use.Footnote 55 This injunction may have stemmed from another order given by the Jesuit General in his instructions to Campion and Persons, that members of the Society should refrain from involvement in affairs of state.Footnote 56 However, given that the anti-Catholic treason laws in England made the mission a dangerous undertaking to begin with, the Jesuit ban on carrying outlawed sacred objects may also have been imposed as an extra safeguard in the event of their capture. The papal faculties for the Jesuit mission to England, compiled separately from those of the Jesuit General, gave no explicit instructions to the Jesuits concerning the dissemination of sacred objects.Footnote 57

The popularity of such items amongst lay Catholics in England, however, was so great that the Jesuit General subsequently relaxed the proscription on their use and circulation by members of the Society working in England. From the late 1580s, both Jesuit and seminary priests played an active role in the distribution of sacred objects to Catholic communities. At the end of 1586, the Jesuit Robert Southwell wrote to Robert Persons, who had left England in 1581 after Edmund Campion’s capture and execution by the Elizabethan authorities, requesting faculties to bless 2,000 rosaries and 6,000 grains of incense to address the demands of the laity for hallowed devotional aids.Footnote 58 In 1592 a priest named Andrew Clark and two other English recusants visited the houses of John Mosman, Thomas Levinson, and Henry Kerr near the border between England and Scotland, bringing agni dei with them as gifts.Footnote 59 In 1597 several captains apprehended a Jesuit in Berwick carrying crucifixes, beads, toy bulls, and agni dei which he had intended to distribute amongst the laity. The same priest had received faculties to dispense absolution to anyone who reconciled themselves to the Roman Church.Footnote 60 The agnus dei also continued to be prized for its protective powers. During the Jesuit John Gerard’s mission to England in the 1590s, he gave an agnus dei embedded with a fragment of the true cross to Richard Burke, the baron of Dunkellin, when the young man begged him to hear his confessions before fighting a duel, saying to Burke ‘you may hope that perhaps for its sake God will protect you from danger and give you time to repent’.Footnote 61 Recalling the duel in his memoirs, Gerard noted that ‘it so happened that God allowed his opponent to make a lunge at his heart; he pierced his [Burke’s] shirt but did not touch the skin’.Footnote 62

The agnus dei and its distribution were therefore closely associated with missionary priests.Footnote 63 Attempts to smuggle the agnus dei and other devotional objects into England and Ireland persisted to the end of Elizabeth’s reign, and continued to serve as links between missionary priests and Catholic laity. The efforts of priests to bring agni dei to the laity suggest that they encouraged resistance of a kind that enabled Catholics to comply, at least in part, with papal demands that they disobey Elizabeth. The involvement of Jesuit and seminary priests in distributing agni dei also sheds light on an aspect of the English mission and its relationship to material culture that merits further consideration.Footnote 64 Trevor Johnson has described the importance of sacramentals in attracting crowds to Jesuit missions in the Upper Palatinate.Footnote 65 Similarly, Liz Tingle has observed the popularity of portable, indulgenced objects such as medals, beads, and rosaries in Counter-Reformation France, especially those objects blessed by the pope.Footnote 66

In the English context, Alexandra Walsham has highlighted the significance of sacramentals to Catholic communities because of the indulgences often associated with them, especially in the absence of priests who could grant absolution of sins and facilitate reconciliation.Footnote 67 Indeed, the exiled English priest Gregory Martin wrote that one of the great attractions of visiting Rome was the prospect of acquiring papal-blessed sacramentals, which had also touched relics in the city and had pardons attached to them.Footnote 68 As a sacramental that carried a papal blessing and which was also popular for its healing and protective abilities, priests may have hoped that the agnus dei would draw greater numbers to the English mission, facilitating both reconciliation (in its multiple senses) and conversion.Footnote 69 The agnus dei’s protective powers, especially over mothers and children, would have made it an appealing gift, and one that might have helped to establish goodwill between the priests and the Catholics to whom they hoped to minister.Footnote 70 It could also, however, act as a mediator of benediction where access to the sacraments was scarce.

The agni dei that Jesuit and seminary priests distributed amongst English Catholics did not always remain with their original recipients. Cuthbert Mayne’s distribution of the sacramentals shows how they could be passed amongst groups of people, and it was common for agni dei to be shared amongst family members. It is telling that many of the agni dei mentioned above and in the following section were circulated in the midlands, the northern counties, and the southwest of England, parts of the country that had strong recusant networks.Footnote 71 Members of Catholic networks who received the sacramentals from missionary priests would also have been able to assist in reconciling other members of their social circles. Distributing the agnus dei to a few members of English Catholic communities, who could then carry on circulating them, would have been a safer and more efficient method of dispersal for the missionaries, who would have increased risk of exposure by approaching recipients on an individual basis.

For Jesuits, this practice also accorded with the instructions of their superiors regarding how they should facilitate the reconciliation and conversion of others. Jesuits were directed to deal only with those who were already reconciled to the Church, and to encourage reconciled lay Catholics to take the leading role in persuading schismatic family members and neighbours to join the faith. When such schismatics were ‘ready to hear the truth’, then Jesuit priests could begin to give them more instruction.Footnote 72 As we have seen, the casuist manuals allowed for the distribution of sacramentals like the agnus dei to schismatics and heretics, in the hope that the powers of these objects would move them to seek reconciliation and conversion. The sharing of sacramentals amongst the laity would have helped to achieve these ends. This method also engaged a greater number of English Catholics in an evangelising process that constituted an act of resistance and disobedience to the queen’s laws.Footnote 73 Circulation of the agnus dei in England was not simply part of the reconciliation process and renewed recognition of papal supremacy, the act of circulation itself served as resistance to the queen and a sign of obedience to the pope.

Confessional politics and the reception of the agnus dei, ca. 1570-1642

Surviving evidence indicates that the efforts of priests to distribute agni dei were well received and they became a potent symbol of confessional difference during the remainder of Elizabeth’s reign. In July 1577 Nicholas Sander received word of a ‘great miracle’ that transpired at a trial in Oxford, when a number of judges, jurors, and attendees at the court were suddenly struck with a mysterious illness during prosecutions of recusants for the veneration of crucifixes and agni dei. According to the report this illness, which Sander believed to be sent by God, killed three hundred people, many of them puritans.Footnote 74 Such narratives highlight the importance of the spiritual disposition of those who handled the agnus dei and sacramentals more generally, but they also acted as a warning to those who threatened them with persecution.

In some cases agni dei were used in bold displays of resistance. The Middlesex session rolls for 1578 recorded the indictments of Eleanor Brome and Elizabeth Barram for wearing agni dei ‘brought into this realm from the See of Rome’. Brome had received hers as a gift from her mother, but the source of Barram’s agnus dei is unknown.Footnote 75 Interestingly, both of these women had been caught wearing the agnus dei in public. Their actions were a remarkably daring statement of their dissent from the established church and government, considering the punishments Brome and Barram faced when caught. Anne Dillon has noted that confraternities of the rosary operated in London with relative openness in the mid-seventeenth century and even held regular processions, albeit in private homes.Footnote 76 The public display of a sacramental known to be blessed by the pope, however, would have been incredibly risky in light of the tensions between Elizabeth I and the papacy throughout her reign.

The agnus dei could also be a mark of those who had been in contact with missionary priests. In 1581 an agent of Francis Walsingham reported a conversation with a man who ‘had certain jewels of Edmund Campions’ and ‘conveyed over in to this Realm of late one Chapman a priest and landed him at Stokes Bay by Portsmouth’. This unidentified smuggler had also brought back ‘three Agnus deis at his last being over, one for his wife, another for his mother, and the last for his sister’.Footnote 77 Here again the links between the agnus dei and the missionary priests may be observed, though it is unclear whether the smuggler obtained his agni dei independently or as a gesture of thanks from the priests he smuggled into England. A search of the Lady West’s house near Winchester in Hampshire in December 1583 revealed a number of contraband devotional objects, including

wrapped in green silk two Agnus dei enclosed in satin broken in many pieces, yet one of them so joined together as the superscription is easy to be read. On the one side is written, Ecce agnus dei qui tollit peccata mundi with the printing of the Lamb, on the other side not altogether so plain seems to be written Pius V papa pont: maximus. And these great letters imprinted in the midst I.H.S.Footnote 78

The search was ordered by the bishop and mayor of Winchester when they received reports that a group of lay Catholics and priests was meeting to hear the Mass in the city.Footnote 79

It is more difficult to determine the extent to which English Catholics perceived the agni dei as political links to Rome, and whether they believed that the possession of an agnus dei constituted an act of resistance that signalled obedience to the papacy. It is certainly telling that many English Catholics chose to keep an agnus dei despite the harsh penalties they faced if caught. Perhaps some believed that the amulets would protect them from any harm the Elizabethan authorities tried to inflict: when John Somerville rode to London in 1583 intent on assassinating the queen, he wore an agnus dei about his neck ‘to defend him from the danger that might ensue unto him upon the attempt’.Footnote 80 Details of the earl of Arundel’s arrest in 1585 illustrate the agnus dei’s potential political connections: at the time the earl was wearing an agnus dei, with a letter from the pope that declared him duke of Norfolk enclosed in its case.Footnote 81 Mary Queen of Scots also seems to have been the recipient of quite a few agni dei in the 1580s. Her custodian, Sir Amias Paulet, was greatly disgruntled when Mary was allowed to receive ‘a box full of abominable trash, as beads of all sorts, pictures in silk of all sorts, with some Agnus Dei’ during her imprisonment at Chartley Hall in Staffordshire in April 1586, and Paulet found a number of agni dei concealed in a casket with pieces of silver in the chamber of her secretary, Claude Nau, during a search of his quarters in September.Footnote 82 It is unclear whether Mary ever distributed agni dei as a token of her patronage, or whether people used them to mark their allegiance to her, but it is possible given the tradition within the wider Catholic community of passing agni dei amongst friends and relatives.

An incident that occurred later in 1586 indicates that Catholics were fully aware of the discs’ political connotations even if they did not necessarily embrace all of them. When the house of George, Bridget, and Elizabeth Brome in Oxfordshire was searched in August, officials found an agnus dei and a pair of blessed beads amongst the belongings of the sisters, which also included several crucifixes and a box of ‘massing cakes’.Footnote 83 Elizabeth Brome had actually tried to smuggle the agnus dei and the beads out of the house before officials found them, but the woman she engaged to carry them away was apprehended and searched at the gates.Footnote 84 The agnus dei was one of many incriminating items in the house: several Catholic devotional texts were found in the library and the sisters’ chambers, including a copy of Edmund Campion’s Rationes Decem and a catechism in English by Lawrence Vaux. The fact that the family tried to hide the agnus dei and beads is a testament both to their precious spiritual value and their highly dangerous political associations.

The potential for links between the possession of an agnus dei and a commitment to resisting Elizabeth and her government are also apparent in Ireland during this period. The agnus dei appears to have attracted comparable interest in Ireland, particularly with the rekindling of the Desmond Rebellion in the late 1570s. Led by James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald, the rebels made Elizabeth’s excommunication central to the justification of their resistance to English rule, declaring that they would be the ‘first and chief instruments’ in the enterprise to deprive Elizabeth of her kingdom.Footnote 85 In his recent biography of Edmund Campion, Gerard Kilroy has discussed how Elizabeth’s government worried that the religious zeal of the Irish rebels might inspire Catholics to instigate open rebellion in England, and how these concerns shaped the crown’s military response to the rising.Footnote 86 In February 1581, the Privy Council ordered the arrest of several Irish students in London in connection with the Desmond Rebellion, upon who were found several agni dei.Footnote 87 Surviving evidence indicates that some of the rebels wore agni dei to protect themselves in battle. In 1582, for instance, William Wendover reported that John Fitzgerald, kinsman and fellow rebel to James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald, went into combat without any armour, believing that the agnus dei he wore about his neck would protect him.Footnote 88 The English government certainly worried about the symbolic power of the agnus dei for the resistance in Ireland. Francis Tucker wrote to Lord Burghley in 1583 to warn him that the Irish bishop of Ross had brought pardons and agni dei back to Ireland after his visit to Gregory XIII in April. They were intended as gifts for those who remained loyal to the pope.Footnote 89

The agnus dei also continued to act as a mark of reconciliation to the Roman Church to the end of Elizabeth’s reign. A memorandum written for the Privy Council in 1591 noted that anyone wearing crucifixes, agni dei, or blessed grains must have been reconciled to the Catholic Church, because otherwise they would not have been permitted to have these things.Footnote 90 A man named Hilary Dakins was identified as a Catholic after he was seen, on several occasions, wearing an agnus dei about his neck. He began to wear the agnus dei after meeting with a seminary priest in 1594.Footnote 91 At the turn of the century William Bowes, the English ambassador in Scotland, reported the activities of John Ogilvy at the Scottish court, calling him ‘a dangerous instrument against God and his church’ who ‘professes himself a Roman Catholic’. Bowes affirmed that he was ‘drawn to believe’ this because he had seen Ogilvy’s ‘Agnus Dei, hosts, and such like Romish Trifles’.Footnote 92

The statute against the bringing of agni dei into the realm remained in place after the death of Elizabeth I in 1603. While notes on priests and agents, who were thought to be smuggling agni dei around England, appear frequently in the state papers of Elizabeth’s reign, fewer appear in those of James VI and I or Charles I. The Stuart rulers had less hostile relationships with the papacy, and none of them were ever threatened with excommunication as Elizabeth had been. Indeed, an agnus dei given to James VI by his wife, Queen Anne, was thought to have saved him when a storm, supposedly orchestrated by witches, beset his ship; Pope Clement VIII, who related this story to the Spanish ambassador in Rome, hoped the incident might move the king to look more favourably on the Roman faith.Footnote 93 When Elizabeth died, the sentence of excommunication and deprivation pronounced against her by the Catholic Church expired. Although the agnus dei remained an important confessional marker and an object of scorn in Protestant polemic, the possession of the sacramental was not as politically dangerous for lay Catholics during the Stuart reigns as it had been in the late sixteenth century. On the other hand, because the agnus dei remained a popular devotional aid well into the seventeenth century, the government continued to use the sacramentals to identify suspected priests in the English missions.Footnote 94

Records and letters from the missions to England in the seventeenth century are filled with accounts of agni dei being used to cure ailments and protect people from natural disasters. Their effectiveness in interactions between Catholics and Protestants was of particular interest to missionaries reporting back to their superiors. Annual letters compiled for 1623, for instance, noted that when a Puritan widow’s house caught fire on the feast of St Andrew, a strong wind prevented her from extinguishing it until one of her Catholic neighbours threw an agnus dei into the flames and made the sign of the cross, which caused the wind to fall and allowed them time to put out the fire. The fire was attributed to divine displeasure at the woman’s derision for Catholic feast days.Footnote 95 Another ‘heretical’ woman who found herself haunted by spirits in 1633 repaired to a local Catholic noblewoman for help, and upon receiving an agnus dei to wear was immediately cured of her visions.Footnote 96 Similarly, the Protestant parents of a twelve-year-old girl resorted to a missionary priest in the residence of St John in 1638, when the child was seized with a sudden illness which left her partially paralysed. The priest gave the girl a small piece of an agnus dei dissolved in water to drink and cured her paralysis.Footnote 97 In all of these cases, the afflicted first sought to repair damage by other means, but only succeeded when they turned to the sacramentals of the Catholic Church for help. In these accounts, the agnus dei acted as a marker of confessional difference, illustrating the failure of heretical, Protestant churches to provide adequate care for their parishioners. While the agnus dei lost some of its more dangerous associations after the death of Elizabeth I, it remained important as a symbol of confessional distinction and as an indicator of the success of the missions to England throughout the seventeenth century.

Conclusion

The agnus dei occupied a complex position in English Catholic life after 1570. Continuous efforts to import and distribute agni dei after 1571 not only point to the strength of English Catholicism, they also suggest that it may have been more closely aligned with the papacy, both politically and spiritually. These efforts may also indicate a more receptive audience for Pius V’s declaration against Elizabeth, and point to the gravity with which English Catholics considered the threat of excommunication against them in the bull. Preservation and veneration of the agnus dei may indeed have served as a spiritual and political connection to Rome, but it also constituted an act of resistance against Queen Elizabeth’s laws of the kind that Pius V demanded when he pronounced her excommunicated and deposed. The apparent popularity of the agnus dei and other devotional objects amongst English Catholics therefore points not only to the vitality of the faith in England: it may also suggest that many within the faith believed the excommunication of their monarch to be legitimate, even if most chose not to make this view public through other means.

The possession and use of agni dei after 1570 acted as a pointed statement of defiance against the Elizabethan regime, if only because the government forced the issue by banning them and associating them with treason. The agnus dei was not the only sacred object targeted by the Elizabethan authorities: blessed rosaries, beads, and crucifixes also came under attack. The proscriptions imposed on these items by parliament in 1571 implicitly imbued them with a political significance with which they had never been associated in medieval or early modern Europe. In these circumstances, the motivations of English Catholics who chose to keep and circulate these items deserve fresh consideration. From the government’s perspective, their actions constituted a symbolic display of resistance to the queen that pointed to the potential of all English Catholics to commit treason and attempt to overthrow her. It is significant that many Catholics continued to collect and employ sacred objects in light of this association. Some may simply have rejected the government’s interpretation of the materials of Catholic devotion, but the agnus dei, at least, raises questions about the nature of political participation amongst Catholics in post-Reformation England, and the extent to which that participation was subversive.

The role of missionary priests in encouraging this culture of resistance through the distribution of sacred objects also merits further reflection. While the involvement of missionary priests in the circulation of prohibited religious books and the ‘sacred economy’ of masses and relics in early modern England has received considerable attention, they also played a central part in the circulation of other sacred objects like the agnus dei.Footnote 98 Although the agnus dei lost its more dangerous political meanings when Elizabeth I died, it remained a popular but illicit devotional object in the seventeenth century. Missionary priests continued to bring agni dei and other prohibited sacred items into England, and their possession remained a significant expression of dissent. From this perspective, the possibilities for political participation within Catholic communities diversify and expand considerably.

At the same time, this process shows continuities between Catholic missions to England and those operating in other parts of the early modern world. The employment of sacred objects like the agnus dei to attract converts and schismatic Catholics back to the Roman fold in England reflect a broader strategy used by missionaries in Europe, Asia, and South America in this period.Footnote 99 The spiritual importance of materials like the agnus dei to the sustenance and survival of Catholicism in England also supports a growing body of scholarship which has emphasised the intellectual, cultural, and devotional connections between members of the English Catholic faith and their counterparts in other regions.Footnote 100 The continued popularity of the agnus dei and other sacred materials in the late sixteenth century illustrates the resilience of ties between English Catholicism, the papacy, and the wider Catholic community, while the subversive significance it assumed during the reign of Elizabeth I embodies the wider political and confessional contexts which made English Catholicism distinct in early modern Europe.