Masks and masking have an extraordinarily long history in Mesoamerica. Still used today for community festivals in the largely indigenous state of Oaxaca, Mexico, masks held multivalent meanings and uses at the time of European contact. As discussed by Harris (Reference Harris1996), Spanish chroniclers recorded native public performances of the sixteenth century replete with games, musical instruments such as teponaztli drums, dances and elaborate costumes incorporating feathers, rattles and masks. Such performances were carried out for purposes as diverse as the enactment of mock battles, the beseeching of deities such as Tezcatlipoca for life-giving rains, or the imitation of elements of the natural world such as ‘certain nocturnal birds of the region’ (Ciudad Real Reference Ciudad Real1976, 369, cited in Harris Reference Harris1996). Regarding many pre-Hispanic societies, the documentation of public performances involving masks may be rarer than the recovery of costuming elements themselves. Such records are nonetheless present in late Postclassic period (ad 800–1521) pictographic codices. As discussed by Cecilia Klein (Reference Klein1986), both material remains and recorded instances of masking by the Aztecs for performances such as deity impersonation are so numerous as to have inspired Lévi-Strauss (Reference Lévi-Strauss, Jacobson and Schoepf1967; Reference Lévi-Strauss1988) to include them among his so-called ‘mask cultures’.

Some of the earliest evidence for Mesoamerican masking appears among initial Early Formative period ceramic artefacts from the Soconusco region of Chiapas and Guatemala, where figurines dating to approximately 1700 bc depict individuals wearing regionally standardized masks (Lesure Reference Lesure1999; Rosenswig Reference Rosenswig and Lesure2011). By the Olmec horizon (1400 bc), a range of media suggests that masks and masking were central to various social events. While Early and Middle Formative period stone masks are perhaps the best-known examples (e.g. Pasztory Reference Pasztory, Clark and Pye2000; Taube Reference Taube2004), there is at least one wooden mask from Guerrero (Griffin Reference Griffin and Benson1981, 212); paintings of masked individuals at Oxtotlitlán Cave (Grove Reference Grove, Sharer and Grove1989); ceramic masks from Central Mexico (Borgheyi Reference Borgheyi1955; Weaver Reference Weaver1953); sculptural depictions of masked individuals (i.e. Guernsey et al. Reference Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010); and miniature masks for figurines (Flannery & Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus2005, 122) and on headdresses (Taube Reference Taube2004, 182). Masks were employed at a variety of scales in the Formative period, from miniature representations adorning figurines to monumental buildings that were dressed in stone or plaster façade masks (Estrada-Belli Reference Estrada-Belli2006; Markman & Markman Reference Markman and Markman1989, ch. 7). The merging of human and non-human features in much Early Formative art has suggested to several scholars (e.g. Guernsey Reference Guernsey2006b; Joyce & Barber Reference Joyce and Barber2015; Pasztory Reference Pasztory, Clark and Pye2000; Reilly Reference Reilly1989) that masks and other forms of costuming were important to political relations by at least the San Lorenzo phase (1400–1200 bc). By the advent of complex polities, ‘masks were important elements in the panoply of display that served to legitimize the rule of the state’ (Couch Reference Couch1991, 48). As we discuss below, masking may have been part of the process by which elites legitimized and reaffirmed authority in the later Formative period.

The association of masking, the face and identity is no accident. For ancient Mesoamericans, the face was considered one of the most important characteristics of the physical body and one closely related to identity. This is well exemplified by ceramic figurines, which often have generic bodies but expressive faces framed by individualizing hairdos, jewellery and representations of body modification (Blomster Reference Blomster, Halperin, Faust, Taube and Giguet2009; Faust & Halperin Reference Faust, Halperin, Halperin, Faust, Taube and Giguet2009; Hepp & Rieger Reference Hepp, Rieger, Orr and Looper2014; R. Joyce Reference Joyce1998, 148, 152–3; Marcus Reference Marcus2018). Masks, which transform the face of a person or object, thus allow the wearer to perform identities related to the mask's features (R. Joyce Reference Joyce1998; Klein Reference Klein1986). In fact, in the animating ontologies of New World peoples, the act of wearing a mask could be more than representational, but also include the merging of human and other identities into those of hybrid beings (Hendon Reference Hendon and Harrison-Buck2012; Houston Reference Houston, Inomata and Coben2006; Mills & Ferguson Reference Mills and Ferguson2008; Vilaça Reference Vilaça2002).

Masks continued to be of profound significance throughout the pre-Hispanic era, with abundant later examples from across Mesoamerica. The lower Río Verde valley of Oaxaca, Mexico, exemplifies this pattern. Archaeological evidence of masking occurs from the Early Formative through the Early Postclassic period in the region (e.g. Barber & Olvera Sánchez Reference Barber and Olvera Sánchez2012; Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Barber2017; Hepp & Joyce Reference Hepp, Joyce and Joyce2013; Jennings Reference Jennings2010). In this paper, we focus on masking in this region during the Formative period. First, we discuss patterns in a collection of masks and masking-related artefacts, along with the contexts from which the objects were recovered. We then suggest that changes over time in the production, use and deposition of masks were intertwined with the development of status inequality and the consolidation of political authority. We explore materiality studies and sensorial archaeology as productive avenues for approaching these artefacts, which were significant in the public performances of the communities who produced them.

Masking and transformation

The archaeological study of masks and masking in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica has paralleled major theoretical trends in the discipline. Early scholars identified mask styles as chronological and spatial markers of archaeological cultures (Borgheyi Reference Borgheyi1955; Caso Reference Caso1969; Sorenson Reference Sorenson1955). Processual archaeologists of the 1960s and ’70s evaluated religious paraphernalia such as masks as part of ritual sub-systems that served to regulate broader social systems (Drennan Reference Drennan and Flannery1976; Flannery Reference Flannery1972; Flannery & Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus1976). Binford (Reference Binford1962; see also Hawkes Reference Hawkes1954) categorized such artefacts as ‘sociotechnic’ (primarily serving to manage social interactions) or ‘idiotechnic’ (primarily serving in contexts related to ideology) items functioning within cultural systems. Critiques of processualism called for a more interpretive study of objects, in which masks could be seen as representations of ideologies or world views, embodiments of gender roles, or as metaphors recapitulating underlying social structures (Cordry Reference Cordry1980; Hansen Reference Hansen1992; R. Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Davis, Kehoe, Schortman, Urban and Bell1993; Markman & Markman Reference Markman and Markman1989). Despite evolving perspectives, studies of pre-Hispanic masks have tended to follow a wider pattern in archaeology in which ‘things’ are seen merely as ‘a means to reach something else, something more important’ (Olsen Reference Olsen2010, 23–4).

Though the study of ritual paraphernalia allows for a more robust elaboration of social institutions such as religion, craft specialization, inequality and trade, recent materiality scholarship has also advocated for more serious consideration of the agency of other-than-human entities whose social lives are entangled with those of their human counterparts (Hodder Reference Hodder2012; Latour Reference Latour2005; Olsen Reference Olsen2010; Pauketat Reference Pauketat2012; Zedeño Reference Zedeño2009). Human social life in ancient Mesoamerica was intimately involved with sacred landscapes, religious objects and texts, musical instruments, plants, animals, ancestors and deities, among myriad others. Further, some objects could modify or completely alter the properties and meanings of other objects, places, or people (Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Barber2017; Joyce & Barber Reference Joyce and Barber2015; R. Joyce Reference Joyce2005; Reference Joyce and Shankland2012; Joyce & Lopiparo Reference Joyce and Lopiparo2005; Zedeño Reference Zedeño2009, 411–13).

In the relational ontologies of pre-Hispanic societies, many objects possessed a life force endowing them with the ability to engage with other beings, to animate other entities and to manifest powerful deities or ancestors (Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Schele, Parker and Kerr1993; Furst Reference Furst1998; Joyce & Barber Reference Joyce and Barber2015; López Austin Reference López Austin1988; Reference López Austin, Nichols and Rodriguez-Alegria2016; Mock Reference Mock1998). Like humans, some other-than-human entities experienced life cycles marked by birth and death ceremonies, as well as the intake of spiritual sustenance required to maintain their animacy (Stross Reference Stross and Mock1998). People and objects often merged to form ‘hybrid’ entities with abilities and properties beyond those of their constituent parts. In Mesoamerica, masks constituted part of the nahual, a cosmologically powerful hybrid that entailed the merging of essences among ritual specialists, animals, ancestors, or deities (Foster Reference Foster1944; Gutiérrez & Pye Reference Gutiérrez, Pye, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010; Hepp & Joyce Reference Hepp, Joyce and Joyce2013; Kaplan Reference Kaplan1956; Rojas Reference Rojas1947; Taube Reference Taube1993). Transformation into a nahual by donning a mask permitted communication with the divine using an alternative ‘face’ (Monaghan Reference Monaghan1995, 99) or ‘skin’ (Galinier Reference Galinier1990, 619) of a deity or ancestor. This process was akin to, and perhaps enhanced by, such activities as the use of hallucinogens, sustained meditation or chanting, dancing, or physical exhaustion producing states of altered consciousness (Carod-Artal Reference Carod-Artal2015; Tedlock Reference Tedlock2005, 142–70).

Materiality studies in archaeology have increasingly benefited from an acknowledgement of the sensorial implications of things and events involving relationships between humans and things (e.g. Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2014; Hepp et al. Reference Hepp, Barber and Joyce2014; Houston & Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000). For Howes (Reference Howes, Tilley, Keane, Küchler, Rowlands and Spyer2006, 169), ‘to truly access the materiality of an object … it is precisely those qualities which cannot be reproduced in photographs—the feel, the weight, the smell, the sound—which are essential to consider’. Drawing inspiration from sensorial anthropology (Feld Reference Feld and Howes1991; Howes Reference Howes and Howes1991a,Reference Howes and Howesb; Reference Howes, Tilley, Keane, Küchler, Rowlands and Spyer2006; Seeger Reference Seeger1975; Reference Seeger1987), archaeologists have explored how past peoples categorized their sensory worlds in ways that may seem foreign to modern Westerners. Western civilization, too, has modified its sensorial hierarchy over recent centuries from one that emphasized smell and tactility to one that prioritizes sight (Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2014, 11; Laporte Reference Laporte2002). The fact that different cultures rank sight above other senses does not indicate that they hold the same understanding of that sense, however. Houston and Taube (Reference Houston and Taube2000, 281) found that the ancient Maya prioritized sight (along with bodily emanations such as breath, speech and song), but also found the eye to be ‘procreative’, an organ that ‘not only receives images from the outer world, but positively affects and changes that world through the power of sight’. For Hamilakis (Reference Hamilakis2014, 15), ‘there is nothing pre-cultural about the bodily senses’. Though it is universally true that human bodies perceive the world through our shared sensorial apparatus (individual variations in sensorial capacity notwithstanding), the cultural interpretation of those senses, and even the ethno-taxonomies categorizing them, are eminently cultural. For Hamilakis (Reference Hamilakis2014, 196), the physiology of the senses is less important than the fact that sensation can ‘produce affectivity’, or inspire emotional responses. It is in eliciting emotions, perhaps, that the sensory aspects of masking are most significant.

The sensory implications of masks are manifold. As extensions of the body, masks direct sensory information to the wearer in novel ways such that they become a part of the body that can act and be acted upon (Dant Reference Dant2004). As objects often meant to be worn, they alter the perception of the wearer by changing, focusing, or limiting sight, hearing, smell and taste. As multi-component objects often incorporated into headgear or even entire costumes (see Couch Reference Couch1991), they may exhaust a wearer by weighing upon the neck and shoulders. They can augment the voice by muffling it or channelling it into a more resonant, perhaps deeper, tone. Through the modification of not only a wearer's appearance, but also her or his voice, a mask thus influences the sensory perception of the wearer as well as that of the audience.

As objects worn during public displays, masks reference the sounds, smells and tastes of the events in which they are involved. As Couch (Reference Couch1991, 14–15) summarized, the majority of pre-Hispanic masks have been lost to deterioration. As artefacts enmeshed in moments of social transformation, masks are the ideal accoutrement for mortuary practices. Often with unpierced eyes and mouths, funerary masks represent one component of the masking practices of ancient New World societies, but may disproportionately comprise the mask collections found today in museums and archaeological repositories. The Mesoamerican Formative period was a time of important socio-political change involving such activities as public celebrations, religious rituals, feasting, sacrifice, music and ball-games. We do well to remember that the masks we recover in archaeological contexts only hint at the sensorial cacophony of Formative period social life. Researchers pursuing the anthropology of the senses (e.g. Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2014, 22; Howes Reference Howes, Tilley, Keane, Küchler, Rowlands and Spyer2006) have referred to the interaction between the senses using the borrowed medical term ‘synaesthesia’. As summarized by Howes (Reference Howes, Tilley, Keane, Küchler, Rowlands and Spyer2006, 162), the term is literally defined as ‘a very rare condition in which the stimulation of one sensory modality is accompanied by perception in one or more other modalities’. Though the term is applied somewhat differently in anthropology, acknowledging the existence of co-acting senses is useful for exploring how non-Western societies conceive of the senses and their taxonomy. By further enriching the discussion of ancient masks with reference to their archaeological associations with other materials and contexts, perhaps we can begin to reconstruct some of the experiences surrounding masking. Central to these considerations must be the conceit that, for the people who used and experienced masks in ancient Mesoamerica, these objects were animate participants in community life (Hodder Reference Hodder2012; Mills & Ferguson Reference Mills and Ferguson2008; Olsen Reference Olsen2010; Pauketat Reference Pauketat2012; Viveiros de Castro Reference Viveiros de Castro2004; Zedeño Reference Zedeño2008; Reference Zedeño2009). The senses are conduits of such agency (Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2014, 196) and are thus intrinsic, even essential to the roles of these agents in moments of major social change such as the Mesoamerican Formative period.

Background of the collection

The lower Río Verde valley is located on Oaxaca's western Pacific Coast (Figure 1). The region has a semitropical climate, deciduous forests and rich agricultural zones fed by the Río Verde, one of Mesoamerica's largest rivers. Sediment cores from the region indicate maize cultivation and anthropogenic land clearance going back into the late Archaic period (Goman et al. Reference Goman, Joyce, Mueller and Joyce2013). To date, only one Early Formative period site (La Consentida) with primary contexts has been investigated in the region (Hepp Reference Hepp2015; Reference Hepp2019a), though a few additional sites have produced probable redeposited Early Formative period materials or promising artefacts identified in surface survey. In the Late and Terminal Formative periods, the area's human population increased significantly and experienced a degree of settlement and political centralization at Río Viejo, the seat of short-lived Terminal Formative (150 bc–ad 250) and Late Classic (ad 500–800) polities (Barber & Joyce Reference Barber, Joyce, Wells and Davis-Salazar2007; A. Joyce Reference Joyce1991; Reference Joyce, Robertson, Seibert, Fernandez and Zender2006; Reference Joyce2010; Reference Joyce and Joyce2013). Following the Classic period collapse of Río Viejo, the region was again the site of political centralization with the establishment of Tututepec, the capital of a Postclassic period Mixtec empire (Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Workinger, Hamann, Kroefges, Oland and King2004; Levine Reference Levine2011; Spores Reference Spores1993).

Figure 1. Oaxaca's lower Río Verde valley with locations of sites mentioned in the text.

For our analysis of Formative period masking in coastal Oaxaca, we have considered a collection of 22 masks or mask representations from approximately 2000 years of occupation at five sites. The sample consists of 15 masks and mask fragments, five effigy vessel or ‘vessel mask’ fragments and two depictions of masks. We have included full-sized masks and mask fragments, miniature masks and mask-like objects and depictions of masks on carved objects or ceramic figurines because these pieces reflect practices of mask use, even if they are not masks per se. Fourteen of the artefacts come from the site of La Consentida, four from Cerro de la Virgen, two from Yugüe, one from Cerro de la Cruz and one from Río Viejo. All but three of the objects are ceramic. Recovery contexts are diverse and include fill (for which dating may be imprecise), occupational surfaces, burials, ritual caches, middens and structures both domestic and public. Though modest, this sample represents a valuable contribution to the discussion of Mesoamerican masking because, unlike many museum examples, the artefacts hail from excavated, datable contexts.

Early Formative masks

The earliest masking evidence in our sample (Figure 2) comes from the Early Formative site of La Consentida (Hepp Reference Hepp2015; Reference Hepp2019a). These artefacts were recovered from diverse contexts including midden, burial fill, domestic structure and earthen architectural fill deposits. Seven AMS radiocarbon dates demonstrate that La Consentida was among Mesoamerica's earliest known sedentary communities (Hepp Reference Hepp2019b). The site has produced evidence of early mounded earthen architecture, diverse social roles and Tlacuache phase pottery of the Red-on-Buff tradition (Hepp Reference Hepp2019a; see also Winter & Sánchez Santiago Reference Winter, Sánchez Santiago, Winter and Sánchez Santiago2014). Like figurines and pottery from the site, these early masks are made of coarse or medium brown clay fired at low temperatures. They are often decorated with a red slip or paint, and in some cases retain holes that were pressed through wet clay before firing and which allowed them to be tied, perhaps to larger, multi-component headpieces. To the extent that these fragments bear identifiable facial features (especially large eyes and noses), they appear anthropomorphic and essentially naturalistic in form. Notably, life-sized mouths have not yet been recovered, suggesting that some early masks may have left the lower face uncovered to permit speech or singing.

Figure 2. Early Formative period masking evidence from La Consentida. (A) Mask or statue fragment from midden. Bears a red paint or slip; (B) Fragment from fill near human burials. Note holes for tying to headgear; (C) Fragment from initial Early Formative period platform fill; (D) Fragment from fill associated with human burial.

The diverse depositional contexts of La Consentida's mask fragments doubtless result in part from sediment transport and redeposition for constructing features such as Platform 1, the largest architectural feature at the site. The presence of mask fragments in other contexts such as a midden, however, implies that their uses were varied and often public. The midden in question contained more bowls (47 per cent) than did other primary contexts at the site (on average 19 per cent). The emphasis on decorated vessel fragments (54 per cent), relative to an average of 7 per cent in other primary deposits, further suggests that the midden resulted from public feasting (Figs 3.A, 3.B). This inference is consistent with other objects from that context being involved in the same public event or events as decorated serving wares. In particular, it suggests that some of La Consentida's masks were worn during communal events that may have involved dancing, pageants, or oratory performances, and which likely incorporated audiences, music and food. The recovery of some of Mesoamerica's earliest known musical instruments (e.g. Fig. 3.C) from La Consentida further supports this interpretation (Hepp et al. Reference Hepp, Barber and Joyce2014). Several additional artefacts from La Consentida demonstrate an emphasis on costume, public performance and the human face. These include a probable effigy vessel (Fig. 3.D) considered in our collection and several items not included in the collection, such as a figurine of a possible ballplayer (Hepp Reference Hepp2019a, fig. 7.10a), figurines bearing diverse clothing and headgear (Hepp Reference Hepp2019a, fig. 7.8) and an anthropomorphic ceramic face recovered near human burials (Fig. 3.E). The sounds, smells, tastes and physical activities of the public events implied by these artefacts would have made them rich, multi-sensory experiences.

Figure 3. Early Formative period artefacts from La Consentida. (A & B) Decorated pottery from midden containing mask fragment (see Figure 2.A); (C) Bird ocarina from ritual cache near human burials; (D) Probable effigy vessel from domestic structure; (E) Probable figurine fragment from near human burials.

Late and Terminal Formative masks

Evidence for figural representation, and human occupation in general, is fairly scant for the Middle Formative period (1000–400 bc) in the lower Río Verde valley. Though the few Middle Formative figurines from the region do include depictions of headgear and body modification (Fig. 4.A), we have no direct evidence of masks from this period (see Hepp & Rieger Reference Hepp, Rieger, Orr and Looper2014; Urquhart Reference Urquhart2010). One of our next indications of masking appears as a Late Formative ceramic fragment with traces of red paint from the site of Cerro de la Cruz (Fig. 4.B). Like the Early Formative examples, this piece is roughly the size of a human eye. Though too fragmentary for definitive identification, it may have come from a statue, appliqué or mask. The hole pressed through the iris is suggestive of the visibility it offered potential wearers.

Figure 4. Middle and Late Formative period artefacts from coastal Oaxaca. (A) Middle Formative body modification and headgear depicted on a figurine from a domestic midden at Corozo (Hepp Reference Hepp2007, 215); (B) Late Formative possible mask fragment from Cerro de la Cruz (Hepp Reference Hepp2007, 204).

The Terminal Formative period saw major political and economic transformations in the lower Río Verde region. The area experienced significant population growth accompanied by increased reliance on maize, widespread construction of monumental architecture, growing status inequality, a brief and tenuous period of political centralization and more numerous and diverse figural representations of people, animals and divinities (Barber & Joyce Reference Barber, Joyce, Wells and Davis-Salazar2007; Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Barber2017; Hepp & Joyce Reference Hepp, Joyce and Joyce2013; Joyce & Barber Reference Joyce and Barber2015). The six Terminal Formative period artefacts in our sample derive mostly from public ceremonial contexts dating between 100 and 250 ad. During this period, the region's largest pre-Hispanic structures were built and used at Río Viejo, monumental facilities were in use at nine other sites, and status inequality was much more pronounced than in earlier centuries. It is perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that the masks and mask-related objects from this era are the most elaborate in our sample.

One example of a mask from the late Terminal Formative period comes from the site of Río Viejo (Fig. 5). This object bears a highly burnished surface, incised and perforated decor and finely appliqued features. Together, these characteristics depict a naturalistic anthropomorphic face (Wedemeyer Reference Wedemeyer2018, 61). The high-calibre manufacture of the mask suggests the work of a seasoned artisan and perhaps the object's ritual value. The eyes are indicated by two symmetrical, oval incisions with punctured pupils that perforate both the physical surface or ‘skin’ of the face and the figurative boundary between the external and internal realms the mask mediates (Wedemeyer Reference Wedemeyer2018, 61; cf. R. Joyce Reference Joyce1998, 148). These pupils transmitted sight to, and in the case of a ‘procreative’ sight, from the object's wearer (Houston & Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000, 263). This object was recovered from a Chacahua phase (ad 100–250) pit resulting from a termination ritual associated with the abandonment of Río Viejo's acropolis in the Terminal Formative period (Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Lucido2012, 61).

Figure 5. Terminal Formative period mask from a termination deposit at Río Viejo's acropolis.

Two more mask-like objects (Fig. 6) are from Cerro de la Virgen, a hinterland site that was contemporaneous with Río Viejo in the Terminal Formative period. The first object (Fig. 6.A) is a small zoomorphic face recovered from colluvial fill near the modern surface. The artefact was mostly decorated with incisions before its firing. The nose is represented by an appliqué of pinched clay that is turned upwards, resembling a snout. The eye is indicated by an oblong incision with a punctured pupil. Two curved incisions depict eyebrows. The artefact's scale suggests it was meant to be worn by a small subject, perhaps a figurine. The smooth edges of the face reinforce the notion that this was a removable miniature mask rather than a face broken from a figurine (Wedemeyer Reference Wedemeyer2018, 160). Although the object's context provides limited information about its use, the mask-like characteristics are consistent with ritual. The masking of a small item, such as a figurine, implies intervention by a human intermediary emplacing the mask, as well as the transformable essence of the object that bore the mask (Hendon Reference Hendon2000; R. Joyce Reference Joyce1998; Klein Reference Klein1986). The artefact's features thus suggest a connection between ritual practice and the production of identity.

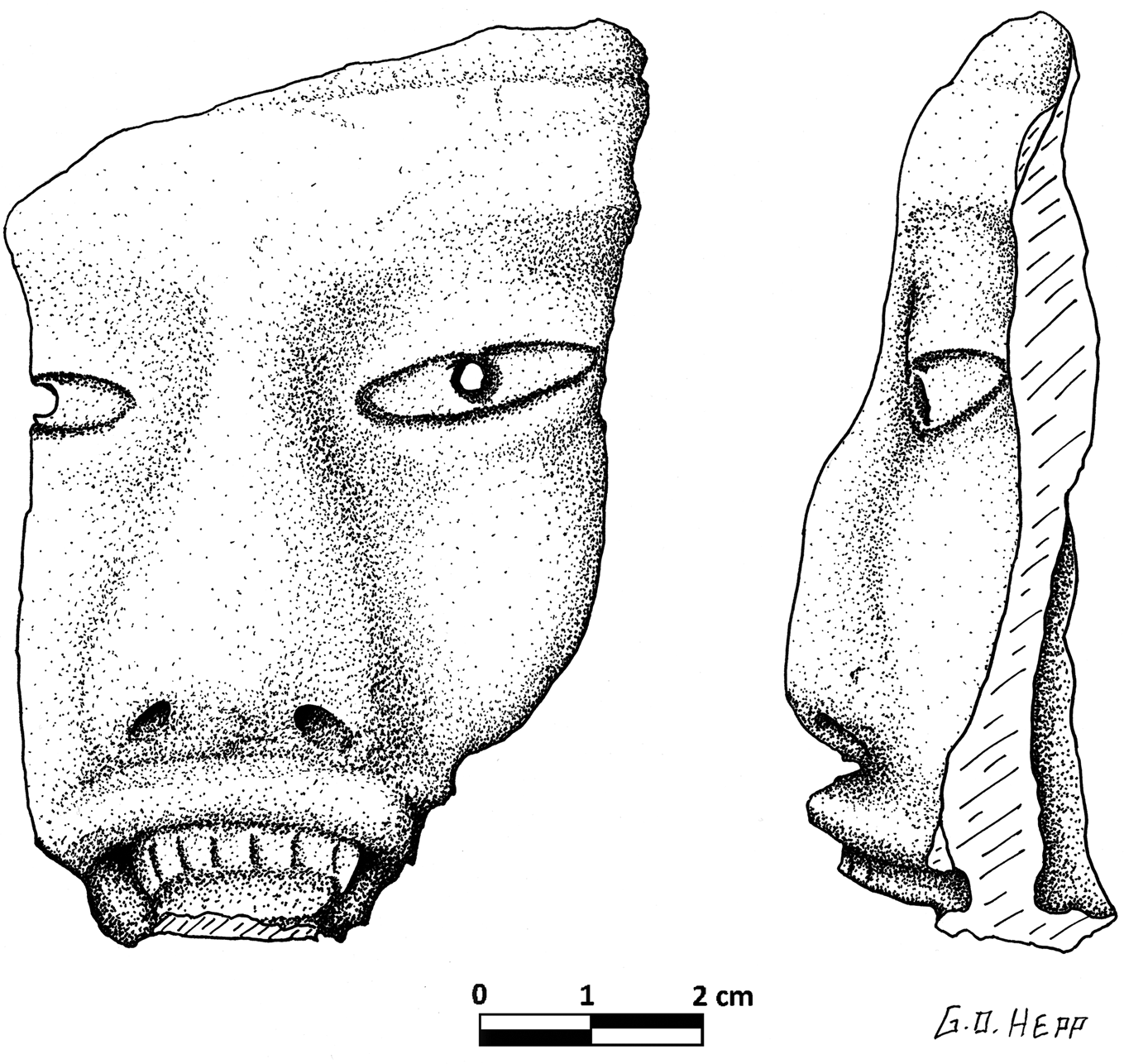

Figure 6. Ceramic masking evidence from Terminal Formative Cerro de la Virgen. (A) Miniature mask fragment from colluvial fill; (B) Fragment from colluvial fill near modern surface.

The second ceramic artefact from Cerro de la Virgen (Fig. 6.B) is a life-sized mask fragment with anthropomorphic features. This item was recovered from colluvial fill near the modern surface in a public area of the site. The object includes appliqués depicting a nose and the upper half of a mouth. The lip is curled back to expose a partial upper row of teeth, suggesting that the artefact likely depicted a wide-open mouth baring its teeth. The fragment's life-sized scale indicates that the original mask could have been worn by a person. Similar depictions of bared teeth may have referenced death and decomposition in Early Formative iconography of the region and could represent ancestors or a death deity (Hepp Reference Hepp2019a, 145–6).

A nearly complete mask and a fragment of a second mask were part of a bundle of five stone artefacts (Fig. 7), also including a figurine and two miniature thrones, set on bedrock prior to the construction of Cerro de la Virgen's most exclusive public building (Brzezinski Reference Brzezinski2019; Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Barber2017). The bundle was likely interred near the beginning of the second century ad and remained a reference point for subsequent renovations of the structure. The nearly complete mask (Fig. 7.A) was made of non-local, fine-grained siltstone and carved in the image of a rain deity, as demonstrated by distinctive flame eyebrows and pronounced incisors, which are characteristic of depictions of highland Oaxacan rain gods. A mask fragment from this offering (Fig. 7.B) was also made of non-local stone. It was possibly broken intentionally along with the other mask, but a partially drilled hole along one of the mask's cracks could indicate that it broke during production, implying local manufacture. While the fragment appears anthropomorphic, it is not possible to determine the identity depicted. The figurine and miniature thrones (Figs 7.C, 7.D) were likely crafted locally. Together, the Cerro de la Virgen bundle, which includes not only masks but also a depiction of a probable bundled ancestor, appears self-consciously to reiterate that enveloping disparate things in novel surfaces is a creative act that can change the properties of any entities involved (Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Barber2017; Guernsey Reference Guernsey2012, 136–7).

Figure 7. Stone artefacts from Terminal Formative period cache at Cerro de la Virgen. (A) Nearly complete rain deity mask; (B) Mask fragment possibly broken during local production; (C) Figurine depicting possible death bundle; (D) Miniature thrones.

Terminal Formative period masking evidence from the site of Yugüe includes two depictions of masked individuals incised into a deer-bone flute and a ceramic bowl. Like the Cerro de la Virgen masks, these items were found in public contexts. The incised flute (Fig. 8.A) was a burial offering placed in the left hand of an adolescent male who was likely a ritual specialist (Barber & Olvera Sánchez Reference Barber and Olvera Sánchez2012; Mayes & Barber Reference Mayes and Barber2008). He was buried in a cemetery located beneath the floor of a public building at the summit of Yugüe's monumental earthen platform. Individuals interred in this cemetery ranged in age from infants to older adults and included females and males. Offerings recovered with these burials, especially the elaborate bone flute, suggest status variation. In other words, this was a burial place for diverse members of the community rather than one restricted to elites. The flute's incised design (Fig. 8.B) depicts the skeletal personification of the instrument producing a sound volute from which emerges the face of a masked anthropomorph. The mask's straight snout and curved incisors, combined with the possible orbital plaques above its eyes, place it within the rain-deity complex (Barber & Olvera Sánchez Reference Barber, Joyce, Wells and Davis-Salazar2012). A second volute, indicating speech or sound, emanates from the masked figure's mouth.

Figure 8. Masking-related artefacts from Terminal Formative period Yugüe. (A) Deer bone flute; (B) Rollout of flute imagery; (C) Incised grayware bowl.

The final example comes from a large, locally produced grayware bowl recovered at Yugüe (Fig. 8.C). The bowl was part of an offering beneath the floor of a restricted public building that also included a large cooking jar, mussel shells, ceramic ear-spool fragments and a figurine fragment (Barber Reference Barber2005). The incised design depicts a masculine anthropomorph in profile wearing a full-face mask with a large eye, a long and upturned snout, and possibly teeth and a curled fang. A sound volute emanates from the subject's mouth. The snout and curled fang are reminiscent of a reptilian being known as yahui in some Mixtec dialects and xicani in some Zapotec dialects, and which appears in the art of highland Oaxaca by as early as the Late Formative period (Brzezinski Reference Brzezinski2011, 108; Urcid Reference Urcid2005). While depictions of this being index several phenomena in later art, most pertain to rulers’ capacity for nagualistic transformation (Hermann Lejarazu Reference Hermann Lejarazu2009). Depictions of animated Formative period masks are also known from the Maya region. Henderson (Reference Henderson2013, 316, fig. 57b), for example, discussed a ‘chin mask’ representing ‘a blended earth-water deity with avian features … at Late Preclassic Kaminaljuyú’.

Discussion

Our sample is limited to 22 artefacts and is inevitably biased by the kinds of contexts from which we have data, as well as by choices of ancient artisans to produce some masks in enduring media while others were likely ephemeral. Nevertheless, based on the contexts from which we have recovered masks, as well as on their iconographic features, it is possible to derive preliminary conclusions about Formative period masking in the lower Río Verde valley. The social significance of masks is underscored by the extraordinary length of time over which they have been produced and used. The earliest known masks appeared alongside the region's first pottery. Rather than implying a remarkable coincidence that these two artefact types appeared simultaneously, this pattern suggests that masks made of perishable, organic materials were used by the Archaic period occupants of the region and have been lost to the ages. Several researchers (e.g. Clark & Blake Reference Clark, Blake, Brumfiel and Fox1994) have suggested that Mesoamerican ceramics themselves developed along a similar trajectory from Archaic period gourd vessels. Indeed, modern masks in Oaxaca are often made with organic materials such as wood, bone, hair and horn, and will leave little permanent archaeological trace (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Modern Oaxacan masks. (A) The festival of Ayuxi in Yanhuitlán. Note the multi-component mask of the dancer at the back; (B) Masked and cross-dressing dancers at a festival in Jamiltepec.

Beginning in the Early Formative period, coastal Oaxacans produced some masks of more durable stuff, and the forms of these artefacts diversified from the earliest anthropomorphic examples to the more specific and ideologically esoteric deity portrayals of the Terminal Formative. Two independent representations of a rain deity in the Terminal Formative period attest to the importance of such beings (and of the phenomena of rain and lightning) during this time. As other researchers have discussed (Covarrubias Reference Covarrubias1957; Flannery & Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus1976; Masson Reference Masson2001; Sellen Reference Sellen2002; Reference Sellen2011; Taube Reference Taube and Benson1995), the Formative period was a time of increasing representations of rain and lightning deities throughout Mesoamerica. Masks such as those found at Cerro de la Virgen were likely integral to rituals bringing living people into contact with, even merging them with, divinities, weather events and powerful animate objects. The association between masks and food has persisted as well. Some of the earliest masks occurred in what were probably public feasting contexts, as do masks in the region today. The depiction of a yahui-masked male at Yugüe was also associated with food, although in a restricted context unlikely to have involved more than a few people.

By the Terminal Formative period, some masks unquestionably became social valuables associated with high status. The most complete stone mask from Cerro de la Virgen (Fig. 7.A) was not only made of non-local stone, but also required masterful artistry, and may have been crafted before its importation (Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Barber2017), thereby indexing the long-distance relationships of the people who produced, acquired and used it. While the Yugüe mask depictions were likely produced locally, both were found in contexts indicating social hierarchy. The flute was part of the burial of an elite ritual practitioner who was also interred with a non-local iron ore mirror, while the grayware bowl was part of an offering within an exclusive ritual space. Both mask depictions at Yugüe, furthermore, draw heavily on iconographic traditions that were either non-local or which developed simultaneously in multiple regions including the Oaxaca coast. Even the production of masks may have gone from a relatively unrestricted endeavour during the Early Formative period (requiring only the knowledge and technology necessary to produce pottery) to a more specialized activity involving artisans producing masks with imported stone and musical instruments and pottery with elaborate incising. The increasing specialization and interregional connectivity tied to masking practices during the course of the Formative period may mirror the expansion of political influence and the concentration of specialized ritual knowledge in the hands of the elite, ultimately resulting in intricate costumes depicted in portraits of rulers and religious experts during the Classic period (ad 250–800). In essence, certain masking practices appear to have gone from being relatively accessible to more restricted and controlled.

This centralization of masks and masking in the hands of the elite, which appears not to have occurred in the lower Río Verde region with other anthropomorphic artefact classes such as figurines (see Hepp & Rieger Reference Hepp, Rieger, Orr and Looper2014; Jennings Reference Jennings2010), provides considerable insight into the nature of Terminal Formative period authority. A similar appropriation of certain anthropomorphic artefacts (such as stone statuary) has been identified elsewhere in Formative period Mesoamerica (see Guernsey Reference Guernsey2012, 144–60; Guernsey et al. Reference Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010). These masks facilitated transformation by providing the face of the wearer with a new outer surface. Based on representations from elsewhere, such as at Oxtotlitlán Cave (Grove Reference Grove, Sharer and Grove1989), masks were sometimes part of elaborate costumes that enveloped entire persons in new skins. There is extensive evidence from across the Americas, both before and after European incursion, that such transformations were far more thorough than simply ‘dressing up’. New outer surfaces turned a subject—be that a figurine, a person, a monument, or even a building (e.g. Guernsey Reference Guernsey, Guernsey and Reilly2006a; Lytle & Reilly Reference Lytle, Reilly, Orr and Looper2013; Markman & Markman Reference Markman and Markman1989, ch. 7)—into a hybrid being. With that in mind, we are struck by the emphasis in the collection not only on sight in general, but on speaking among the Terminal Formative period masks in particular. Mask depictions in the collection denote speech, as do the open mouths of masks and miniature masks. Mask wearers likely merged with the beings who were represented on and who animated the masks, thereby speaking not as mere humans, but rather as manifestations of divine entities or as hybrid beings (Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Barber2017; Klein Reference Klein1986). The fact that at least some Early Formative period masks appear to have left the mouth uncovered, while some later masks modified the voices of their wearers, further implies the significance of oratory performance. Restriction in the production and accessibility of masks thus reveals a funnelling of certain kinds of divine access into the hands of a few people whose authority was partly derived from their capacity to transform themselves into other kinds of beings.

Today's Oaxacan masks are multi-component objects incorporating organic and inorganic materials such as wood, cloth, paint and animal hair and horn. The face portion is often tied to a larger piece of headgear (Fig. 9.A). This appears to be an ancient practice, as indicated by fastening holes on some early masks from La Consentida. Though obviously influenced by thousands of years of history and the impact of European traditions and world-views, modern Oaxacan masks hint at the public practices, rites of passage and establishment of community identity (sometimes called communitas) that characterized the public gatherings of Mesoamerica's past (Turner Reference Turner1969; see also Hill & Clark Reference Hill and Clark2001).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia for sanctioning the excavations and analyses on which this paper is based. We are particularly indebted to the President and the Consejo de Arqueología, the directors of the Centro INAH-Oaxaca, the Presidencias de Tututepec de Melchor Ocampo and Jamiltepec and personnel at Cuilapan de Guerrero. Funding for this study was provided by the: National Science Foundation (BNS-8716332, BCS-0096012, BCS-1213955, BCS-0202624, BCS-1123388, BCS-1123377); Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies (#02060, #99012); National Geographic Society (grant 3767-88); Wenner-Gren Foundation (GR. 4988); Fulbright Foundation (Grantee ID: 34115725); H. John Heinz III Charitable Trust; Explorers Club; the Association of Women in Science; the Women's Forum Foundation of Colorado; Sigma Xi; Colorado Archaeological Society; the University of Colorado at Boulder; the University of Central Florida; Vanderbilt University Research Council and Mellon Fund; and Rutgers University. This paper has benefited from comments by Catharina Santasilia, Julia Guernsey and anonymous reviewers.