Scholars have uncovered numerous effects of personality on the individual's political behaviours, identities and opinions (see, for example, Blais and St-Vincent, Reference Blais and St-Vincent2011; Caprara and Vecchione, Reference Caprara and Vecchione2017; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty and Dowling2011; Mondak, Reference Mondak2010). The majority of research regarding the political effects of personality relies on the Big Five framework (McCrae and Costa, Reference McCrae, Costa and Wiggins1996; McCrae and John, Reference McCrae and John1992). While many personality models exist, the Big Five model (or five-factor framework) proposes that five traits summarize the basic tendencies guiding individuals through their actions, feelings and thoughts. The five traits are agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and openness to experience (Costa et al., Reference Costa, McCrae and Löckenhoff2019; McCrae and John, Reference McCrae and John1992; McCrae and Costa, Reference McCrae, Costa, Boyle, Matthews and Saklofske2008). The Canadian Election Study (CES) has measured these personality traits since 2011. These data offer interesting opportunities to assess how personality affects the political outlook of the Canadian electorate. However, very few studies have used this battery to investigate the role of personality in Canada (see Blanchet, Reference Blanchet2019). The Canadian case is interesting because it offers new insights into how personality affects voters in a political environment where partisanship can be fragmented and volatile (Johnston, Reference Johnston2013, Reference Johnston2017).

Using CES data from three different elections (2011, 2015 and 2019), this article aims to answer two fundamental questions: Are personality traits reliable in the CES? And what are the implications of the Big Five regarding ideology and partisan identity in Canada? On the one hand, we seek to test the reliability of the Big Five measurement in the CES. The battery used, the Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI), despite its popularity, is sometimes unreliable (see, for example, Ludeke and Larsen, Reference Ludeke and Larsen2017; Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Poropat and Mell2014). We observe that while the measurement is not ideal, it produces findings similar to those in the literature (for example, Chiorri et al., Reference Chiorri, Bracco, Piccinno, Modafferi and Battini2015; Mondak and Halperin, Reference Mondak and Halperin2008), except for the trait of agreeableness in 2015, which displays a problematic inter-item correlation (0.05). On the other hand, a recent cross-national analysis showed that personality traits’ effects tend to vary across countries (Fatke, Reference Fatke2017). We expect the Canadian context to produce different patterns in the relationship between traits, ideology and partisanship than in other countries. First, we look at various ideology measures: a self-reported scale and two indexes (market liberalism and moral traditionalism). We find differences across the measures: all five traits are associated with at least one of the two ideological dimensions, while only openness, extraversion and conscientiousness are linked to self-reported ideology. We argue that a two-dimensional measurement of ideology provides a more nuanced and precise estimate of traits’ impacts. Second, we estimate the associations between personality and partisanship. Only three traits—openness, extraversion and agreeableness—affect the attachment to political parties at a statistically significant level.

Literature

Personality

Personality is defined as enduring dispositions reflecting coherence in one's behaviours, thoughts and feelings over time (McAdams and Olson, Reference McAdams and Olson2010; McCrae and Costa, Reference McCrae, Costa, Boyle, Matthews and Saklofske2008). These characteristics are regrouped with several traits that will, together, describe an individual's personality. These traits tend to appear early in life and to be stable over time (McCrae and Costa, Reference McCrae and Costa2003). Shaped by genes and the non-shared environment, personality traits influence a wide variety of human attitudes, behaviours and identities (Costa et al., Reference Costa, McCrae and Löckenhoff2019; McCrae and Costa, Reference McCrae, Costa, Boyle, Matthews and Saklofske2008; Ludeke and Larsen, Reference Ludeke and Larsen2017). Several models have been developed to account for these dispositions, including the HEXACO (Ashton et al., Reference Ashton, Lee and de Vries2014), the Dark Triad (Paulhus and Williams, Reference Paulhus and Williams2002) and the Big Five (McCrae and Costa, Reference McCrae, Costa, Boyle, Matthews and Saklofske2008). While most of these models have been used in political science, the Big Five model has emerged as dominant in psychology and, more broadly, in social science (Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty and Dowling2011). Personality is understood, in this context, as basic tendencies influencing citizens’ attitudes, feelings and behaviours. Hence, in the political arena, personality will give individuals inclinations toward certain attitudes or behaviours. For instance, extraverted people are more likely to attend political meetings and rallies (Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty and Dowling2011; Mondak, Reference Mondak2010). In short, personality creates general tendencies in citizens toward certain attitudinal and behavioural “frames.” These tendencies interact with other factors, such as genetics and the environment. So while personality does not determine one's attitudes, it creates certain patterns leading individuals to specific attitudes.

The Big Five model proposes that five traits define personality and shape individuals’ basic tendencies that guide them through life (McCrae and John, Reference McCrae and John1992; McCrae and Costa, Reference McCrae, Costa, Boyle, Matthews and Saklofske2008). The five traits are extraversion (action, sociability and self-confidence), agreeableness (or agreeability; sympathy, modesty and altruism), conscientiousness (discipline and order), neuroticism (or emotional instability; sadness and anxiousness) and openness to experiences (curiosity and being receptive to new ideas) (McCrae and Costa, Reference McCrae, Costa, Boyle, Matthews and Saklofske2008). These traits summarize individual personality in a wide variety of cultures (McCrae and Terracciano, Reference McCrae and Terracciano2005; Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Allik, McCrae and Benet-Martínez2007).

Due to space constraints in public opinion surveys, the measurement of personality traits is quite challenging, since batteries must measure traits effectively with few items. Traditional personality batteries ask respondents how well statements (words or sentences) describe them (McAdams and Pals, Reference McAdams and Pals2006). The variable corresponding to a trait is built by combining all the items linked to it. The number of items varies greatly across instruments. The most accurate batteries are quite extensive (for example, the NEO-PI-R contains 240 items; see McCrae and Costa, Reference McCrae, Costa, Boyle, Matthews and Saklofske2008). While the length of a battery usually ensures psychometric validity, the batteries are often too long to be inserted in questionnaires that do not focus on personality. Thus, researchers began to develop shorter batteries to integrate personality traits into general surveys. Short batteries have several advantages: in particular, they are practical, since they do not take much time to complete (Credé et al., Reference Credé, Harms, Niehorster and Gaye-Valentine2012). These batteries are usually reliable at the psychometric level (see, for example, Myszkowski et al., Reference Myszkowski, Storme and Tavani2019). However, the literature tends to be cautious with them (Ludeke and Larsen, Reference Ludeke and Larsen2017); for instance, short batteries tend to be less effective in eliminating measurement errors (Credé et al., Reference Credé, Harms, Niehorster and Gaye-Valentine2012).

Personality in the Canadian context

Numerous studies have analyzed how personality traits affect individuals in the political arena (for example, Caprara and Vecchione, Reference Caprara and Vecchione2017; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty and Dowling2011; Mondak, Reference Mondak2010; Mondak and Halperin, Reference Mondak and Halperin2008). Turnout, vote choice and attitudes have been mainly studied in the United States and Europe (for example, Barbaranelli et al., Reference Barbaranelli, Caprara, Vecchione and Fraley2007; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty and Dowling2012; Schoen and Schumann, Reference Schoen and Schumann2007; Vecchione et al., Reference Vecchione, Schoen, González Castro, Cieciuch, Pavlopoulos and Caprara2011). Research regarding the political effects of personality traits has been surprisingly rare in Canada; instead, scholars have sought to measure and understand the impact of a leader's personality (Amsalem, Reference Amsalem, Zoizner, Sheafer, Walgrave and Loewen2020; Bittner, Reference Bittner2011; Blais, Pruysers and Chen, Reference Blais, Pruysers and Chen2019; Joly et al., Reference Joly, Hofmans and Loewen2018; Pruysers and Blais, Reference Pruysers and Blais2019). For instance, Scott and Medeiros (Reference Scott and Medeiros2020) observe that, compared to citizens, municipal politicians display higher scores in extraversion, openness and neuroticism. Others have analyzed the impact of personality traits on individual opinions and behaviours (Pruysers et al., Reference Pruysers, Blais and Chen2019; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Pruysers and Blais2020). Pruysers (Reference Pruysers2020) and Pruysers et al. (Reference Pruysers, Blais and Chen2019) analyzed how the Dark Triad and the HEXACO influence attitudes toward refugees, good citizenship and civic duty. Nevertheless, few studies have analyzed the role of the citizen's personality in Canada (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Pruysers and Blais2020; Gravelle et al., Reference Gravelle, Reifler and Scotto2020). Blais and St-Vincent (Reference Blais and St-Vincent2011) examined the effects of four traits (altruism, shyness, efficacy and conflict avoidance) during the 2008 federal election. They show that these traits influence interest in politics, civic duty and the propensity to vote. Further, their model demonstrates that the effects of traits on the propensity to vote are mediated by political interest and civic duty. More recently, Blanchet (Reference Blanchet2019) uses the CES 2015 and the 2012 American National Election Study to investigate the components of openness to experience and their impacts on political knowledge and interest. The analysis shows that open individuals tend to be more interested but not systematically more knowledgeable. In short, several variables such as attitudes, political interest, political knowledge and the propensity to vote have been studied in Canada with various personality traits, such as altruism, selfishness or standard models (HEXACO and Dark Triad). Still, we know little about how personality measured with the Big Five affects ideology and partisan identification in Canada.

Ideology

As stable and core tendencies, traits will affect ideology by creating enduring patterns in thoughts that are unlikely to change due to political events (McCrae and Costa, Reference McCrae, Costa and Wiggins1996). Traits will therefore influence how individuals view and understand the political world. Several previous studies have analyzed how personality affects ideology (Fatke, Reference Fatke2017; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty, Dowling and Ha2010; Mondak, Reference Mondak2010; Osborne et al., Reference Osborne, Satherley, Sibley, Mintz and Terrisforthcoming). This research tends to find that openness is associated with liberalism (left-wing/progressive ideology) and conscientiousness with conservatism (right-wing ideology) (see Bakker, Reference Bakker2017; Carney et al., Reference Carney, Jost, Gosling and Potter2008; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Golden and Socha2013; Fatke, Reference Fatke2017; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty, Dowling and Ha2010; Mondak, Reference Mondak2010; Sibley et al., Reference Sibley, Osborne and Duckitt2012; Osborne et al., Reference Osborne, Satherley, Sibley, Mintz and Terrisforthcoming). People with a high score in openness exhibit positive responses to novelty and new ideas. Thus it is plausible to link this trait to the endorsement of liberal and progressive ideas, both socially and economically (Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty and Dowling2011). Conscientiousness is associated with rigidity, tradition and the respect of norms. Therefore, the association between this trait and conservatism can be attributed to reluctance about social changes, adherence to existing norms and rules and an emphasis on the importance of self-responsibility (Fatke, Reference Fatke2017; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty, Dowling and Ha2010, Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty and Dowling2011). The results concerning the three other traits are mixed. Extraversion is usually not related to ideology (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Golden and Socha2013; Mondak, Reference Mondak2010; Schoen and Schumann, Reference Schoen and Schumann2007). People high in agreeableness tend to be more altruistic and empathetic. They should, theoretically, be more inclined toward a left-leaning ideology, but the results are inconsistent (Fatke, Reference Fatke2017; Mondak, Reference Mondak2010). Finally, findings concerning neuroticism are unclear. Although individuals high on this trait prefer the status quo, studies tend to find an association with leftist ideas (Fatke, Reference Fatke2017; Carney et al., Reference Carney, Jost, Gosling and Potter2008; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty, Dowling and Ha2010) or no relationship (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Golden and Socha2013).

These studies, however, face two critical challenges. First, their conceptualization of ideology as a single dimension (left/right) is limited (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Golden and Socha2013; Mondak and Halperin, Reference Mondak and Halperin2008; Mondak, Reference Mondak2010). Scholars have argued that especially in Canada (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Nevitte, Blais, Everitt and Fournier2012), ideology should be a two-dimensional structure (Feldman, Reference Feldman, Huddy and O2013). Several studies have opted for this approach (for example, Carney et al., Reference Carney, Jost, Gosling and Potter2008; Fatke, Reference Fatke2017; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty, Dowling and Ha2010). For instance, Bakker (Reference Bakker2017) finds that personality traits have different impacts on economic and social ideology in Denmark, the United Kingdom and the United States. He demonstrates that traits do not systematically influence all dimensions of ideology and that the effects vary by country. Therefore, studies need to consider the dual structure of ideology when estimating personality's relevance for these beliefs.

Second, as Feldman (Reference Feldman, Huddy and O2013) argues, the literature's inconsistencies may be due to cultural and national variation in the meaning of ideology. This idea is partly corroborated by Fatke (Reference Fatke2017), who examined ideology and personality traits in 21 countries. Using pooled data, he finds that all traits except conscientiousness are associated with left-leaning ideology. Moreover, he demonstrates that neuroticism and conscientiousness affect both economic and social policy preferences, while extraversion, agreeableness and openness influence only the latter. Finally, Fatke (Reference Fatke2017) estimates these relationships for every (mostly non-Western) country in his sample, and shows that it is difficult to generalize the results since the associations are inconsistent across countries. This conceptualization leads to a more nuanced and fine-grained understanding of the impacts of personality on ideology.

We expect to find similar patterns in Canada because its ideology is comparable to other Western countries (Sibley et al., Reference Sibley, Osborne and Duckitt2012). Openness to experience and conscientiousness should predict a self-reported ideology to the left and the right, respectively. Individuals with a high score in the former tend to be more open to novelty and new ideas, leading them to adopt progressive and leftist ideas. Since individuals with a high score in conscientiousness prefer tradition and norms and tend to be more resistant to change, we expect this trait to be associated with a right-wing ideology. Agreeableness promotes empathy, which can be linked to progressive and protective positions promoted by the left. We should then find a positive link between left-wing ideology and agreeableness. Extraversion measures sociability but also assertive personalities, and these individuals tend to have dominant positions and value orderly society. Considering the mixed findings in the literature, we do not expect this trait to affect ideology. We have no clear expectations for neuroticism, since the literature does not observe an association between this trait and ideology.

Partisan identification

According to the social-psychological model, an affiliation to a political party goes beyond instrumental attachment and is considered an identity, like religion or race (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960). Psychologically speaking, we can refer to partisan identification as a self-concept, which can be defined as how citizens understand their own identity (Greene, Reference Greene1999, Reference Greene2000). Self-concepts are formed by characteristics of adaptations (that is, values, motivations and others), social environment, and basic tendencies or personality traits (Costa et al., Reference Costa, McCrae and Löckenhoff2019; McCrae and Costa, Reference McCrae, Costa, Boyle, Matthews and Saklofske2008). Scholars have sought to estimate how personality affects partisan identification in the United States and Europe (see, for example, Mondak and Halperin, Reference Mondak and Halperin2008; Schoen and Schumann, Reference Schoen and Schumann2007; Vecchione et al., Reference Vecchione, Schoen, González Castro, Cieciuch, Pavlopoulos and Caprara2011). Results link openness and agreeableness to progressive (leftist) parties, and they link conscientiousness and neuroticism to conservative (rightist) parties (Aidt and Rauh, Reference Aidt and Rauh2018; Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Hopmann and Persson2015; Mondak, Reference Mondak2010). Extraversion's impact is inconsistent, since some studies find a relationship with right-wing identification, while others do not (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Hopmann and Persson2015; Vecchione et al., Reference Vecchione, Schoen, González Castro, Cieciuch, Pavlopoulos and Caprara2011).

That being said, to our knowledge, this association has never been investigated in Canada. The Canadian context is a particularly interesting one to study the impact of personality on partisan identification. Although the social-psychological nature of partisan identification has been contested in Canada, studies have demonstrated that Canadians hold stable identification and that this affiliation is essential when analyzing elections (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Blais, Everitt, Fournier and Nevitte2006; Blais et al., Reference Blais, Gidengil, Nadeau and Nevitte2002). For instance, Gidengil et al. (Reference Gidengil, Nevitte, Blais, Everitt and Fournier2012) analyze 2004, 2006 and 2008 CES data and find that partisanship is meaningful, particularly when considering only respondents with strong identification (fairly strong and very strong). This strategy allows us to identify the “real” partisans, who hold a stable attachment (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Nevitte, Blais, Everitt and Fournier2012).

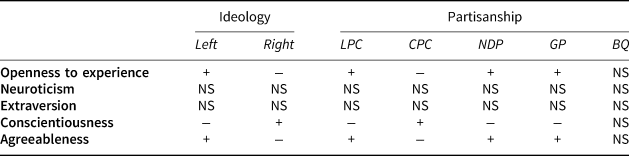

The Canadian national political context is composed of two major parties, the Liberal party of Canada (LPC) and the Conservative party of Canada (CPC), along with three minor parties that have never formed the government. The LPC is seen as a centre-left party that most of the time holds left-leaning ideas and sometimes has a right-leaning agenda because of its “catch-all” strategy. We expect that people high in openness and agreeableness will identify with this party. The CPC is a right-wing party promoting more traditional values and the reduction of social programs in order to attain a deficit-free budget. Since this party defends the status quo and traditional values, we posit that individuals with a high conscientiousness score will be more likely to identify with this party. We also expect these relationships to be inverted: openness and agreeableness will be negatively related to identification with the CPC, while a high score in conscientiousness will be negatively linked to identification with the LPC. The New Democratic party (NDP) and Green party (GP) are both to the left of the LPC. The NDP is the traditional party of union members and proposes a more socialist approach to politics, while the Green party holds a radical approach favouring environmental protection. Thus we should observe a positive relationship between those parties and openness to experience and agreeableness traits and a negative association for conscientiousness. Lastly, the Bloc Québécois (BQ) is a nationalist party whose goal is to promote Quebec's interests at the national level until it obtains its independence. This party is only present in the province of Quebec. Since this party does not primarily align itself on the left/right continuum, we would expect to not find significant links with personality traits. We should observe links similar to those found in the ideology section because partisan identification is interconnected with ideology; however, we should not be surprised to find weaker links, since Canada's partisan structure can be quite volatile (Johnston, Reference Johnston2017). It is only since the 2000s that citizens could systematically identify Canadian political parties on the left/right dimension correctly (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015). Thus this dimension is arguably not totally embedded in the partisan structure, compared to countries such as the United States. Furthermore, Canadian parties tend to be reluctant to self-identify with this dimension, even when their public discourse clearly puts them on it (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015). The election studied in this analysis also features significant changes in terms of power possession and leadership. Table 1 summarizes our expectations.

Data and Method

Data

This study takes advantage of the measurement of personality traits in the CES of 2011, 2015 and 2019. Personality traits are measured using the TIPI, which asks respondents how a pair of words (that is, facets of traits) describes them (Gosling et al., Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann2003).Footnote 1 The TIPI has been repeatedly validated as being consistent with longer batteries (Gosling et al., Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann2003; Myszkowski et al., Reference Myszkowski, Storme and Tavani2019; Romero et al., Reference Romero, Villar, Antonio Gómez-Fraguela and López-Romero2012), with a few exceptions (Credé et al., Reference Credé, Harms, Niehorster and Gaye-Valentine2012). Despite the psychometric “equivalence” with longer batteries, the TIPI—and small scales in general—tend to have a weak internal coherence (Chiorri et al., Reference Chiorri, Bracco, Piccinno, Modafferi and Battini2015; Mondak and Halperin, Reference Mondak and Halperin2008). For instance, Ludeke and Larsen (Reference Ludeke and Larsen2017) show that the TIPI's implantation in Wave 6 of the World Values Survey is problematic: some items from the same traits are negatively correlated. In summary, short batteries seek to measure the content of the traits validly, sometimes to the detriment of the internal coherence (Myszkowski et al., Reference Myszkowski, Storme and Tavani2019; Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Poropat and Mell2014). Yet despite this low internal consistency, short scales can be as reliable as long measurements (Heene et al., Reference Heene, Bollmann and Bühner2014; Woods and Hampson, Reference Woods and Hampson2005; Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Poropat and Mell2014).

We assess the impact of personality on the political views of Canadians. To do so, we use four dependent variables. The first one is self-reported ideology. While this variable is among the most studied in political science, we do not yet know if personality affects ideology in Canada. According to Gidengil et al. (Reference Gidengil, Nevitte, Blais, Everitt and Fournier2012), ideology plays a large role in Canadian political behaviour. The question wording stayed the same in all the election surveys: “In politics, people sometimes talk of left and right. Where would you place yourself on the scale below (0–10).” A high value on this measure means a self-report to the right side of the spectrum, and a low score signifies a self-report to the left. While this measure seems reliable because of its widespread use, many are critical of the simplification and linearity of this kind of “Downsian” measure (Feldman, Reference Feldman, Huddy and O2013; Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Nevitte, Blais, Everitt and Fournier2012). The major problem with the left/right simple continuum is that it does not account for two central concepts of the left and right: economic and moral attitudes. For example, a person can favour social economics and more redistribution while being more traditional about social values. To overcome this difficulty, we picked up two of the ideological scales from Gidengil et al's (Reference Gidengil, Nevitte, Blais, Everitt and Fournier2012) Dominance and Decline: market liberalism and moral traditionalism. These two scales, which were developed for the Canadian context, constitute our second and third dependent variables. The advantage of such multi-item scales is that survey respondents are less likely to overestimate or underestimate their ideological positioning. Also, using numerous items to measure a latent construct is more precise than using a single measure (Ansolabehere et al., Reference Ansolabehere, Rodden and Snyder2008). The market liberalism scale is composed of the degree to which respondents agree to five prompts: (1) “When businesses make a lot of money, everyone benefits, including the poor.” (2) “The government should leave it entirely to the private sector to create jobs.” (3) “People who don't get ahead should blame themselves, not the system.” (4) “If people can't find work in the region where they live, they should move to where the jobs are.” (5) “How much do you think should be done to reduce the gap between the rich and the poor in Canada?” We had to deviate from this scale in the 2019 election because the question about business benefiting everyone was not asked. We replaced it with “The government should take measures to reduce differences in income levels.” It is also important to note that the question of finding a job was worded differently in 2019: “If people really want to work, they can find a job.” While these modifications are not optimal, we believe the scale still measures the same latent construct. The Cronbach's alpha for each year was 0.57 (2011), 0.63 (2015) and 0.71 (2019).

The second ideological dimension captures moral values. The moral traditionalism scale is an assemblage of responses to four prompts: (1) “Society would be better off if fewer women worked outside the home.” (2) “How much do you think should be done for women?” (3) “How do you feel about gays and lesbians?” (0–100 thermometer scale) (4) “How do you feel about feminists?” (0–100 thermometer scale). In contrast to the market scale, the moral scale questions were identical in each CES iteration. The Cronbach's alpha for each year was 0.56 (2011), 0.61 (2015) and 0.7 (2019). Both scales range from 0 to 1. In the market liberalism scale, 0 means skepticism about the free market, and 1 expresses the opposite. A lower score on the moral traditionalism scale embodies progressive attitudes, and a higher score denotes conventional views about society. To test the robustness of both scales, we performed an item analysis for each item of the scales through each year in order to test the monotonicity assumption of a summated rating scale. We ran a bivariate correlation of each item against the scale's rest score—that is, excluding the correlated item from the scale. Removing the item from the correlation is important because it would have otherwise created an upward bias in the correlation. Performing this analysis revealed that each item is monotonously related to the scale, which means that we can rely on our scales.Footnote 2

The fourth dependent variable is partisan identification. We kept the five main parties that held seats in the legislature at least once across the three elections (Liberals, Conservatives, NDP, Bloc Québécois and Greens). Five dichotomous variables measure partisanship, where 1 refers to the supported party (partisans) and 0 to an affiliation with one of the four other parties.Footnote 3 Following Gidengil et al. (Reference Gidengil, Nevitte, Blais, Everitt and Fournier2012) and the particular structure of partisanship in Canada, only fairly strong and very strong identifiers are considered in the analysis as partisans, in order to reveal those who have a more intense socio-psychological attachment.

Models

We test the impact of personality traits on ideology and partisan identification in Canada with ordinary least square (OLS) regressions and robust standard errors. OLS regression is a better way to communicate and interpret results with dichotomous variables than logistic regression in non- and experimental settings (Angrist, Reference Angrist2001; Angrist and Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2008; Gomila, Reference Gomila2020; Hellevik, Reference Hellevik2009). OLS regressions have several benefits over nonlinear models, such as logistic regressions. First, they display directly interpretable coefficients representing the percentage point of a one-unit increase. Second, linear regression is the best approximation of a trait's effect on our dependent variables (Angrist and Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2008; Gomila, 2020).Footnote 4 To attain more precise estimates, we add two control variables that are likely to influence political behaviour and personality, as well (Pearl, Reference Pearl2000): age and gender. Figure 1 represents how these variables affect the model.

Figure 1 Directed Acyclic Graph

With these variables, we aim to control for how the environment can affect the formation of personality. Studies show that personality is relatively stable but in constant development throughout one's life (Costa et al., Reference Costa, McCrae and Löckenhoff2019; McAdams and Pals, Reference McAdams and Pals2006). Age is therefore an important variable to account for in our models. Gender can also affect personality by having an impact on the social environment and through differences in brain structures (Nostro et al., Reference Nostro, Müller, Reid and Eickhoff2017). While most research controls for socio-demographics or political variables, such as interest in politics, we modelled the equation to estimate the total effect of personality on ideology and partisanship. Ultimately, our model is very parsimonious and effective.Footnote 5

Results

TIPI: Reliability

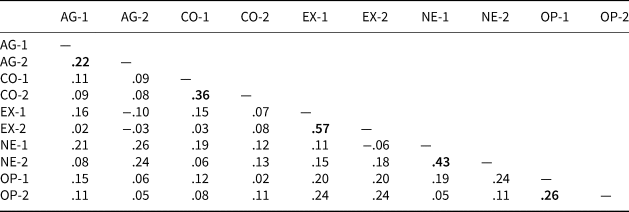

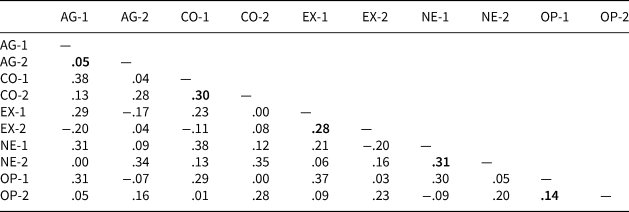

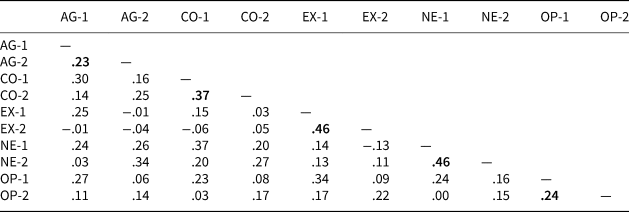

To examine personality measurement consistency, we computed correlation matrices for each of the TIPI items (Tables 2 to 4 in the Appendix). This method aims to assess how reliable the measurement of personality is in the CES (Ludeke and Larsen, Reference Ludeke and Larsen2017).Footnote 6 Out of the five personality traits, agreeableness showed some of the lowest correlation coefficients. The value is 0.22, 0.05 and 0.23 for 2011, 2015 and 2019, respectively. Such a low value in 2015 is concerning and might signal a questionnaire error or a generalized misinterpretation of one of the questions. Thus the regression analysis with this trait should be interpreted with caution. The second-lowest average score is found for openness, with 0.26 in 2011, 0.14 in 2015, and 0.24 in 2019. The three other personality traits benefit from higher coefficients for each election year. Conscientiousness has 0.36, 0.30 and 0.37; extraversion has 0.57, 0.28 and 0.46; and neuroticism has 0.43, 0.31 and 0.46. While low scores for agreeableness and openness can be problematic, it is important to point out that correlations between the TIPI items are generally low, in the 0.25–0.50 range (Chiorri et al., Reference Chiorri, Bracco, Piccinno, Modafferi and Battini2015; Gosling et al., Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann2003; Mondak and Halperin, Reference Mondak and Halperin2008). The literature suggests that this internal coherence is a weakness of the TIPI but that the psychometric validity remains intact (Myszkowski et al., Reference Myszkowski, Storme and Tavani2019; Romero et al., Reference Romero, Villar, Antonio Gómez-Fraguela and López-Romero2012).

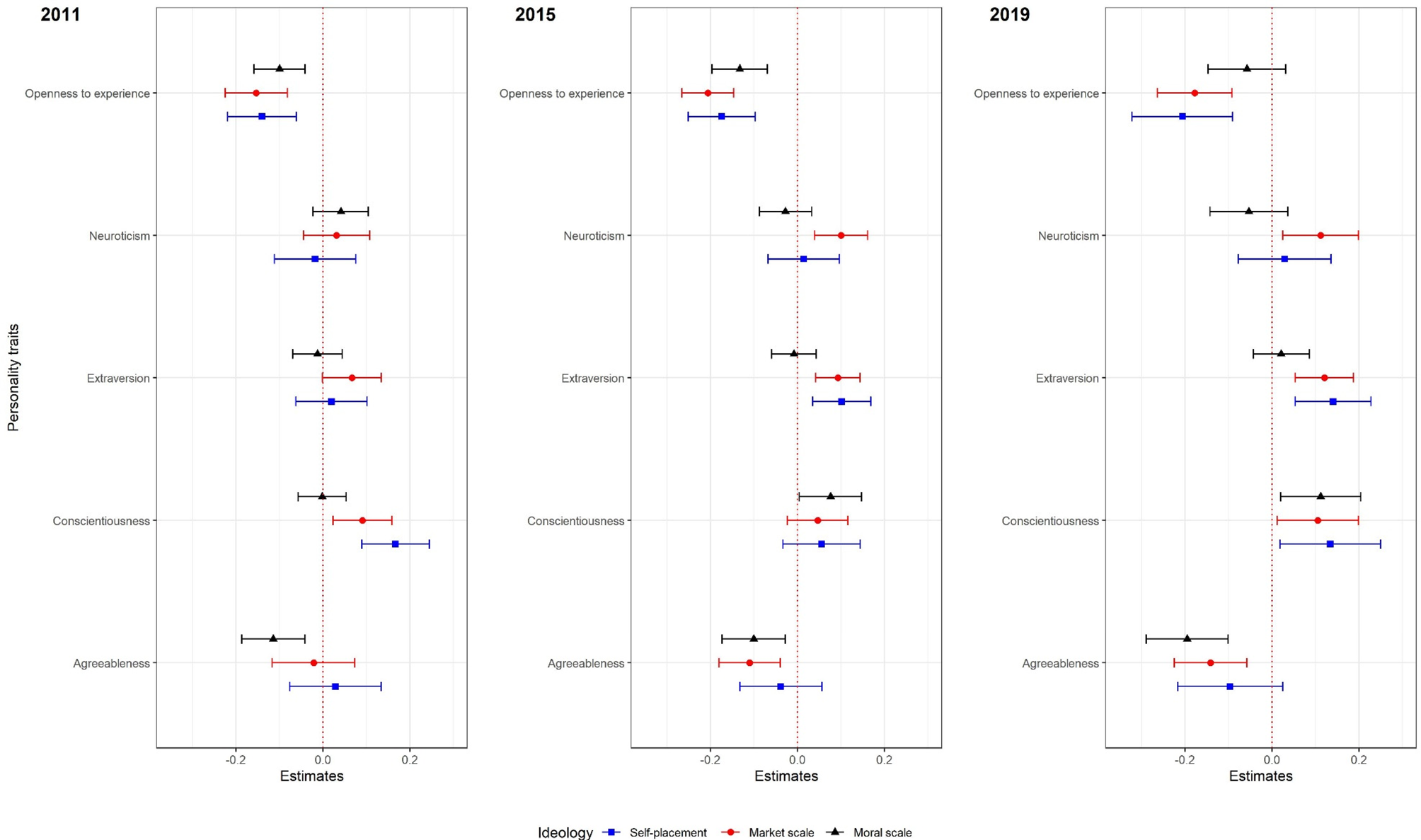

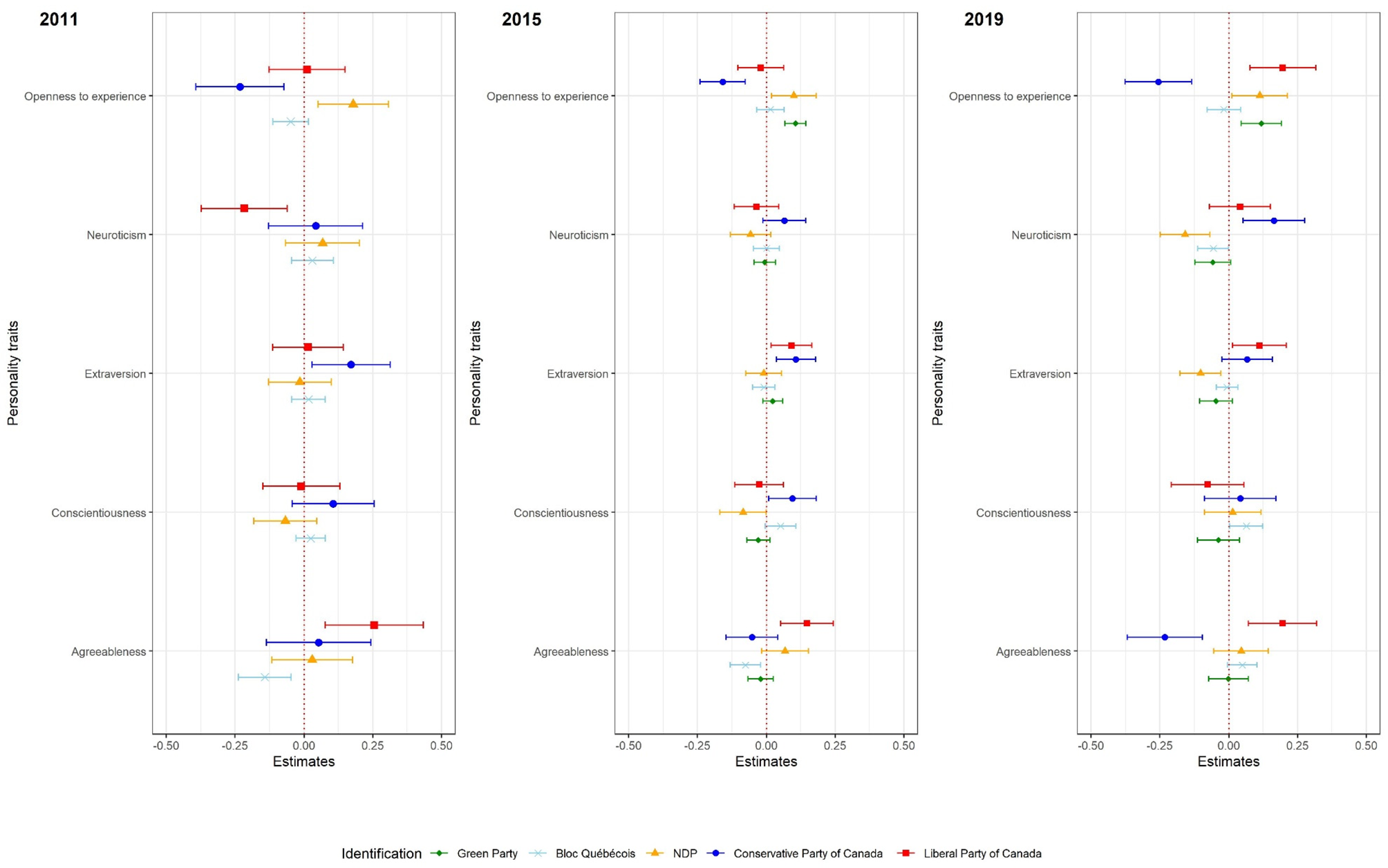

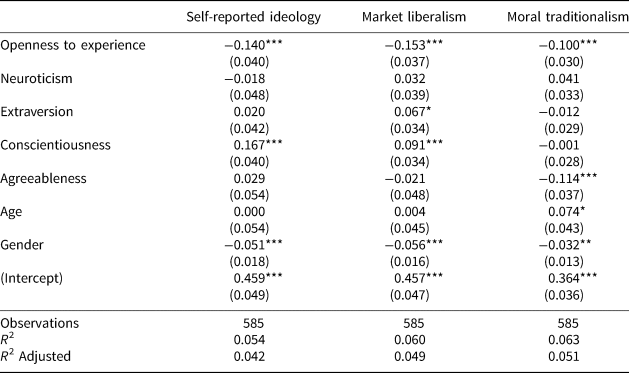

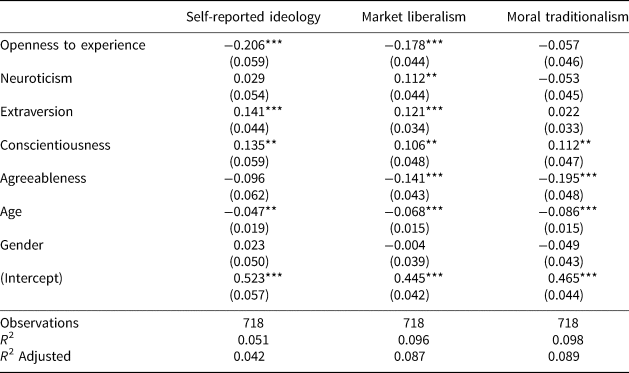

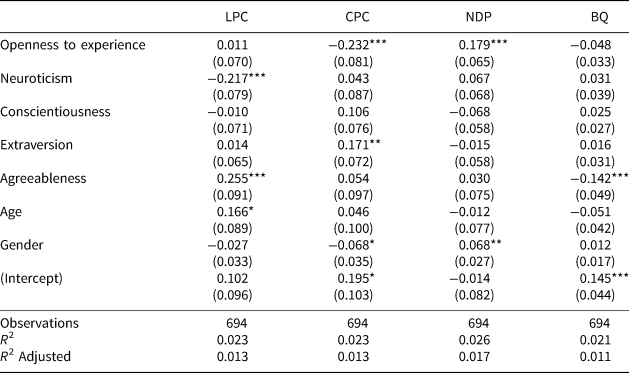

Next, we examine the links between personality and political beliefs. The Big Five's impacts on self-reported ideology, market liberalism and moral traditionalism are depicted in Figure 2, while the relationship with partisanship is illustrated in Figure 3 (Tables 5 to 10 in the Appendix).

Figure 2 Impacts of Personality Traits on Ideology

Note: Points are the estimates from the OLS regressions (robust standard errors and 95% confidence intervals). The complete regression tables are available in the Appendix.

Figure 3 Impacts of Personality Traits on Partisan Identification

Note: Points are the estimates from the OLS regressions (robust standard errors and 95% confidence intervals). The complete regression tables are available in the Appendix.

Openness to experience

Across all three elections, openness to experience holds a negative and statistically significant effect on all the dependent variables except for the moral traditionalism scale in 2019. The coefficients range from −0.10 to −0.20 for ideological self-placement. In other words, results show that openness to new experiences is associated with a self-report on the left of the political spectrum. Figure 2 shows similar results for social and economic conservatism, where this trait is related to left-wing attitudes (except for moral traditionalism in 2019). Turning to partisan identification, we find that the association between openness and identification with the CPC is negative and consistent across elections. Open individuals are less likely to think of themselves as a Conservative. Moreover, openness is the strongest personality predictor for CPC identification. On average, across the three elections, a person at the highest level of openness (1) is 19 percentage points less likely to identify with this party, in comparison to a person at the lowest level (0). In both 2015 and 2019, openness is positively linked with Green party identification. Openness increases the probability of identifying with the Greens by 10 points (2015) and 11 points (2019). The effect of the trait on identification with the NDP is positive and significant for every year. On average, it increases the probability of identifying with this party by 12 points. Contrary to our expectations, openness was correlated to LPC attachment only in 2019. Overall, we demonstrate that openness to experience plays an essential role in Canadian citizens’ ideological and partisan development. In accordance with our expectations (Table 1), the trait increases the probability of holding left-wing attitudes, positioning oneself on the left and identifying with a party of the left (NDP and Green) and not the one on the right (CPC).

Table 1 Summary of Expectations

Neuroticism

As predicted in Table 1, neuroticism has a limited effect on ideology. Results from Figure 2 reveal that this trait only has an impact on market liberalism in two elections; that is, emotionally unstable and more anxious individuals are more likely to endorse free-market attitudes in 2015 and 2019. This trait also has a limited impact on partisan identification. We observe several unique associations with the LPC (2011), the CPC (2019), the NDP (2019) and the Green party (2019). We interpret these inconsistencies across the years as an indication that neuroticism does not substantially affect party identification in Canada.

Extraversion

We find that extraversion is associated with an ideological self-placement on the right in 2015 and 2019. People with a high score for this trait are more likely to report right-wing positions. For each extraversion unit increase, we observe an increase of 7 and 11 points, respectively, in 2015 and 2019. For the market liberalism scale, extraversion has a positive and statistically significant effect across the three elections. Extraverts are more prone to agree with conservative views of the economy, such as limited governmental intervention in the economy. Extraversion is, however, not associated with moral traditionalism. This trait appears to be relevant to partisan identification only for the CPC and the LPC. It is positively associated with conservative identification in 2011 and 2015 and liberal identification in 2015 and 2019. Contrary to our expectation in Table 1, extraversion does have a significant relationship with both ideology and partisanship in Canada by pushing individuals toward the right and toward the favouring of free-market ideas.

Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness affects self-reported ideology: individuals with a high score for this trait are more likely to report a right-leaning ideology in two out of the three elections studied (2011 and 2019). Figure 2 also exhibits positive and statistically significant relationships between market liberalism and conscientiousness in 2011 and 2019. This trait also positively and statistically significantly affects the moral traditionalism scale (2015 and 2019). These results confirm Table 1 ideology expectations. As for the partisan identification, we found a link in 2015 and 2019 with the Bloc Québécois, which is quite surprising considering that we did not expect that personality would reveal a pattern for attachment to the BQ. While this party directly advocates for drastic changes such as Quebec's independence, it has taken some conservative stances on moral values, notably on secularism. That said, contrary to our expectations, conscientiousness hardly influences partisanship in Canada.

Agreeableness

Results regarding agreeableness show that this trait does not significantly affect self-reported ideology in Canada (if we ignore the significant estimate of 2015, since the inter-item correlation is problematic). Agreeableness has a consistently negative effect on moral traditionalism: it decreases the probability of adhering to traditional attitudes by an association ranging from 0.1 in 2011 to 0.2 in 2019, suggesting that agreeable individuals hold more progressive social values. The influence of this trait on market liberalism is negative and significant in 2015 and 2019, meaning that those who are more agreeable are more skeptical about free enterprise and the limited role of government in the market. While displaying null results on the self-reported variable, agreeableness follows predictions from Table 1. Agreeableness is significantly linked to identification with only one party: it promotes an affiliation with the LPC, increasing the probability of identifying with this party by 25 points in 2011 and by 19 points in 2019. While agreeableness is negatively and significantly related to CPC affiliation in 2019, we do not find this link in 2011. We also found significant links between this trait and the BQ. However, taking into account results from 2011 and 2019 only, the coefficients run in opposite directions.

Discussion

Ideology and partisanship are two central variables in political behaviour. However, we know little about how psychological factors affect these attitudes and identity in Canada. In this study, we posit that personality might be able to partially explain why citizens adopt certain political stances and affiliate with particular political parties. Personality will influence how people understand the political arena, as well as their positions on specific issues, by influencing most human actions and thoughts; the political realm is not free from those patterns.

Since 2011, the CES surveys have measured personality traits in Canada, but these data have rarely been used in research (Blanchet, Reference Blanchet2019). While several questionnaires exist to measure the Big Five personality traits, short batteries, such as the TIPI, have become increasingly popular in extensive surveys, including the CES. However, literature shows that this type of battery can sometimes lead to internal coherence issues (Chiorri et al., Reference Chiorri, Bracco, Piccinno, Modafferi and Battini2015; Credé et al., Reference Credé, Harms, Niehorster and Gaye-Valentine2012; Ludeke and Larsen, Reference Ludeke and Larsen2017). For instance, two items forming a given trait can be uncorrelated or even negatively associated. This situation can have serious implications for future research. We therefore explore the reliability of the measurement of personality traits in the CES. Performing inter-item correlations, we find that traits’ measurements are weakly correlated but are performing as well as studies typically find (Chiorri et al., Reference Chiorri, Bracco, Piccinno, Modafferi and Battini2015; Gosling et al., Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann2003; Mondak and Halperin, Reference Mondak and Halperin2008), with the exception of agreeableness in 2015. Overall, our results show that the CES measured personality traits reliably. We conclude that the CES measurement of personality (2011 to 2019) is not problematic for further examination of personality's effects.

We then examine the implication of personality traits for the Canadian electorate's self-reported ideology. Results show that right-wing ideology is associated with conscientiousness and left-wing ideology is associated with openness, which is in concordance with the literature's common findings (for example, Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Golden and Socha2013; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty and Dowling2011). People high in openness tend to favour left ideology because they are more likely to accept novelty and change. On the flip side, conscientious individuals prefer tradition and rules, encouraging them to adopt right-wing ideology. Although studies tend to find that extraversion is unrelated to ideology (Alford et al., Reference Alford, Funk and Hibbing2005; Mondak, Reference Mondak2010; Schoen and Schumann, Reference Schoen and Schumann2007), we observe that this trait is associated with a right self-placement in 2015 and 2019 (Carney et al., Reference Carney, Jost, Gosling and Potter2008; Fatke, Reference Fatke2017). Agreeableness and neuroticism both had null effects on self-placement, suggesting they do not affect ideological self-perception. Overall, our findings indicate that in Canada, three traits matter for self-reported ideology: openness, conscientiousness and extraversion. This finding is similar to the trends typically observed in the United States and Europe. That said, personality seems to have a less binding effect in Canada than in other countries regarding self-reported ideology.

Yet the measurement of ideology as a single dimension is limited (Fatke, Reference Fatke2017; Feldman, Reference Feldman, Huddy and O2013; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty, Dowling and Ha2010; Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Nevitte, Blais, Everitt and Fournier2012). We thus assessed this belief with two additional dimensions: market liberalism and moral traditionalism. This analytical strategy is optimal, since these dimensions have been validated in Canada (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Nevitte, Blais, Everitt and Fournier2012) and allow more flexibility to represent personality's impact on ideology. Indeed, the results demonstrate that every trait is associated with market liberalism in at least two elections. Specifically, we uncover that people high in openness and agreeableness are less likely to endorse these attitudes, while conscientious, neurotic and extraverted individuals are more likely to display them. Personality traits in Canada appear to have a strong connection to economic attitudes. We find limited support for associations between personality and moral traditionalism. Agreeableness and openness both increase the probability of having progressive social values, while conscientiousness promotes conservative values. The divergence between economic and social conservatism is particularly interesting. Echoing the study of Bakker (Reference Bakker2017), we find that traits seem to display different relationships with ideology when they are measured with more than one dimension. We observe that personality traits are mostly linked in Canada to economic attitudes—namely, whether people agree or disagree with a free and open market. However, these relationships do not transfer to social views (moral traditionalism) about society.

Results overwhelmingly suggest that personality is more binding for the economic axis in Canada. Using fine-tuned measures of ideology allows the regression models to better represent the impacts of traits. Thus, Canadians’ personality traits seem to influence mostly the economic dimension of ideology. The analysis demonstrates that personality matters particularly for the expression of ideology: all traits significantly affect at least one of the two dimensions, providing nuance to the null findings based on self-reports. Overall, we show that personality plays an essential role in shaping Canadian citizens’ understanding of the political world. This finding offers interesting insights into the roots of citizens’ ideologies. We demonstrate that an ideology is not purely instrumental; instead, psychological factors play a modest role in the way individuals understand their political environment.

The next step of our analysis was to estimate the impacts of personality traits on partisanship. We observe that four traits affect partisanship in more than one election. People high in agreeableness are more likely to identify with the LPC. It could be speculated that being positioned in the centre of the Canadian party system helps stimulate the perception that the LPC is a more consensual party, which could attract highly agreeable Canadians. While agreeableness correlates with left-wing ideology, it fails to transpose into adherence to the most leftist parties, namely the NDP and Green party. Open individuals are less prone to identify with the Conservatives and more likely to be a partisan of the NDP or Green party. Individuals with a high score for extraversion identify more with the CPC and LPC.

Prior research typically finds that personality matters to explanations of party identification. This relationship has been highlighted in a number of countries, including Germany (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Hopmann and Persson2015; Schoen and Schumann, Reference Schoen and Schumann2007), the United Kingdom (Aidt and Rauh, Reference Aidt and Rauh2018), the United States (Barbaranelli et al., Reference Barbaranelli, Caprara, Vecchione and Fraley2007; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty and Dowling2011, Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty and Dowling2012; Mondak, Reference Mondak2010), and across Europe (for example, Aidt and Rauh, Reference Aidt and Rauh2018; Vecchione et al., Reference Vecchione, Schoen, González Castro, Cieciuch, Pavlopoulos and Caprara2011). However, our results show limited impacts of personality on partisan identification in Canada compared to these countries. We find an association in less than 30 per cent of the cases. Moreover, contrary to the situation in the United States and the United Kingdom, where parties are clearly divided ideologically, the effects of personality are not a mere reflection of the association found with ideology. Although similar, the association between personality and partisanship in Canada differs. For instance, conscientiousness is associated with a self-reported right ideology but is not related to identifying with the CPC. This situation can be explained by the nature of party identification in Canada. Party identification tends to be weaker than in other countries, which makes the social-psychological model, although relevant, less powerful (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Nevitte, Blais, Everitt and Fournier2012). Furthermore, Canadian political parties are reluctant to identify with an ideological dimension, which can blur the similarities between our variables (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015). Hence, the effect of personality is less salient, since it does not contribute to a stable identity. However, attitudes tend to be more stable than partisanship, which can explain the association with ideology. We posit that since the Canadian partisan structure is much more volatile than in other contexts, it explains the weaker links found in our analysis between personality and partisanship (Johnston, Reference Johnston2013, Reference Johnston2017). Moreover, these results cast some doubt on the application of the social-psychological nature of partisan identification in Canada. If partisanship was conceived as a self-concept, as it is in other countries such as the United States (Greene, Reference Greene1999, Reference Greene2000), personality should matter, since it directly influences self-concepts (McCrae and Costa, Reference McCrae, Costa, Boyle, Matthews and Saklofske2008). This analysis does not mean that partisanship is irrelevant to the study of Canadian political behaviours; instead, it shows that partisanship in Canada is not deeply embedded in psychological factors such as personality traits.

This study is, however, not without limitations. We aimed to estimate the impacts of personality traits on ideology and partisanship with simple but effective models (Pearl, Reference Pearl2000). These models’ objective is to capture the total effects of traits on our variables, which can lead to high coefficients. However, this type of modelling is not perfect: other valid mechanisms can be hypothesized to explain traits’ impacts. For example, we might suppose that the effects of traits are indirect (see, for example, Caprara and Vecchione, Reference Caprara and Vecchione2017; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty and Dowling2012). Further, personality's impact is inconsistent in the elections studied. Many traits had an impact in specific years, while being indistinguishable from zero in others. This difference could be caused by the measures of personality traits. The CES did not use the same survey question in 2011, which can perhaps explain why these election results are not as consistent as those from the 2015 and 2019 elections. These inconsistencies also demonstrate the importance of the social environment. While personality offers basic tendencies to individuals, the social environment also profoundly influences citizens’ attitudes. In the Canadian partisan system, a leader's personality and performance, as well as exogenous events such as the economic and social context, can heavily influence the degree to which individuals affiliate to a party and, therefore, the impacts of personality. Measurement with the TIPI is also more prone to null results than larger batteries (Bakker and Lelkes, Reference Bakker and Lelkes2018). Specifically, short batteries tend to produce larger measurement errors, leading to null results. One could expect that this study's association underestimates the relationship between personality and political outcomes.

The results of this study raise questions about the effects of personality in Canada. We show that personality traits do not necessarily resemble results seen in the United States or the United Kingdom, despite some similarities between the countries. We believe that future research must be conducted in Canada to examine which mechanisms apply to this context and if similar results can be found with full personality batteries. We encourage future research to examine the role of personality in Canada and its impacts on party identification, vote and other political identities and behaviours. Moreover, these results underline the need for more cross-national analysis of the political effects of personality. This type of study would be particularly beneficial as a way to understand the role of the party and partisan structure. We believe that more research is needed on a wider variety of political contexts to fully uncover the effects of personality.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Patrick Fournier and the three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions.

Appendix

Correlations matrices

Table A2 Correlation Table, 2011

Table A3 Correlation Table, 2015

Table A4 Correlation Table, 2019

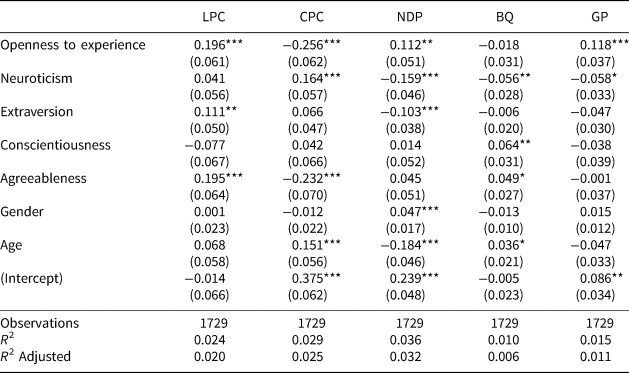

Regression tables

Table A5 Regression Table of the Association between Personality Traits and Ideology (2011)

Table A6 Regression Table of the Association between Personality Traits and Ideology (2015)

Table A7 Regression Table of the Association between Personality Traits and Ideology (2019)

Table A8 Association between Personality Traits and Partisanship (2011)

Table A9 Association between Personality Traits and Partisanship (2015)

Table A10 Association between Personality Traits and Partisanship (2019)