Article contents

Names and Naming in Aristophanic Comedy*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

One of the ironies of literary history is that the survival of Aristophanic comedy and indeed of all Greek drama is due to the more or less faithful transmission of a written text. Reading a play and watching one, after all, are very different sorts of activities. Unlike a book, in which the reader can leaf backward for reminders of what has already happened or forward for information about what is to come, a play onstage can be experienced in one direction only, from ‘beginning’ to ‘end’. Nor can a play be put down and picked up again at one's leisure or interrupted while the audience puzzles over a difficult or intriguing passage. Live theatre is an ephemeral and essentially independent thing, which must be experienced in its own time and on its own terms or not at all, and as a result we modern readers, dependent on the written page, are at a marked disadvantage in understanding ancient drama. Taplin's study of staging in Aeschylus has shed considerable light on the dramatic technique of Athenian tragedy. Stage-practice in Aristophanic comedy, and in particular the ways in which names and naming are used there, has received much less attention.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1992

References

1 Taplin, O., The Stagecraft of Aeschylus: The Dramatic Use of Exits and Entrances in Greek Tragedy (Oxford, 1977Google Scholar); Taplin offers a useful basic summary of his critical principles on pp. 18–19.

2 On Aristophanic staging, see Dearden, C. W., The Stage of Aristophanes (University of London Classical Series, 7) (London, 1976Google Scholar); an updated study of the question would be welcome. Coulon, V., Aristophane, i (Paris, 1923), p. xxxiGoogle Scholar, makes some brief but salutary remarks on the names of Aristophanic characters. Dover, K. J., Aristophanic Comedy (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1972), pp. 6–10Google Scholar, also has some helpful observations on the subject but is generally literary in his approach. Henderson, J., Aristophanes' Lysistrata (Oxford, 1987CrossRefGoogle Scholar), is good on individual names but for obvious reasons never discusses the issue in general terms. Taplin (n. 1) never deals specifically and at length with the question of the verbal identification of characters (although note the brief remarks at p. 10), presumably because his orientation is so overwhelmingly visual and because (as I argue below) this is rarely a problem in tragedy.

3 That this is a primarily literary rather than dramatic convention is apparent from the fact that all characters must do in order to be identified in our texts is speak a line, even from the wing. Simple physical presence onstage, on the other hand, is not enough to warrant notice in our texts. (This is not to deny that modern critical editions usually include κωφ⋯ πρ⋯αωπα in the initial list of characters.)

4 For a systematic discussion of the evidence, see Lowe, J. C. B., ‘The Manuscript Evidence for Changes of Speaker in Aristophanes’, BICS 9 (1962), 27–39Google Scholar. Gomme, A. W. and Sandbach, F. H. (edd.), Menander: A Commentary (Oxford, 1973), pp. 40–1CrossRefGoogle Scholar, treat the question briefly and cite further bibliography.

5 Thus in Euripides' Bacchae, for example, Cadmus' name is given in 10, well before he appears onstage at 178; Pentheus is named at 44 although he does not enter until 212; Agave is mentioned by name already in 229 (if that line is authentic) and at least by 507 but only appears onstage at 1168. The use of names and naming in connection with the entrance of tragic characters is mentioned but never discussed in and of itself by Webster, T. B. L., ‘Preparation and Motivation in Greek Tragedy’, CR 47 (1933), 117–23.Google Scholar

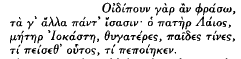

6 Thus in Oedipus the King Oedipus appears onstage at 1 and gives his own name at 8; the character who appears at around 78 and speaks first at 87 is identified as Creon at 79 (cf. 85); Teiresias is addressed by name by Oedipus at 300 (cf. 285) when he first appears onstage; Jocasta's name is given by the Chorus at 632 as she enters from the palace. In Bacchae Dionysus reveals his own name in 1–2; Teiresias enters at 170 and identifies himself by name at 173; he also makes it clear at 170 that the other old man who enters at 178 is Cadmus; Pentheus is identified in an entrance announcement at 212–13 when he makes his initial appearance onstage; Agave is identified by name by the Chorus at 1166 as she enters for the first time.

7 Compare the remarks of Taplin (n. 1), p. 27.

8 Compare Arist. Po. 1451b15–16. The best evidence for tragedies with completely nontraditional plots is Aristotle's reference to Agathon's Antheus at Po. 1451b20–21. I must stress that I am discussing specifically the issue of names and characters rather than specific plot-lines here; one can have a general sense of (e.g.) who Oedipus is without having any idea of exactly what he is going to say or do next.

.

Antiphanes' character may be exaggerating a bit here in order to make the situation of the comic poet appear more difficult by contrast but his basic point seems sound. A generation later Aristotle can assert about the mythical stories used in tragedies that ‘even the ones that are known are known only to a few, but all the same they provide pleasure to everyone’ (κα⋯ τ⋯ γνώριμα ⋯λ⋯γοις γνώριμ⋯ έστιν ⋯γγ' ὂμως ε⋯ϕρα⋯νει π⋯ντας Po. 145Ib25–27). This would certainly not have been true for any fifth-century Athenian who had sat through even a year or two's worth of tragedies in the Theatre of Dionysus, and Aristotle's remark probably reflects the results of a gradual change in Athenian education in the fourth century; compare the remarks of Else, G. F., Aristotle's Poetics: The Argument (Cambridge, MA, 1957), pp. 318–19.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

10 Cf. Arist. Po. 1451b11–14. The extremely scanty evidence for the procedure called the proagon is collected and discussed by Pickard-Cambridge, A., The Dramatic Festivals of Athens2 (Oxford, 1968), pp. 63, 67–8Google Scholar. Before the festival began poets appeared in public along with their unmasked actors before a restricted (if perhaps still substantial) audience in the Odeion and announced the subject of their upcoming production. There is no reason to believe that a detailed description of the action of the play was required. The fact that the actors appeared unmasked, in fact, argues strongly against this interpretation of the ceremony. When comedies were re-performed at smaller, local festivals, of course, some members of the audience undoubtedly knew the characters' names (and a great deal else) in advance. All the same, it seems fair to assume that Aristophanes composed his plays with a single, crucial initial performance at one of the great festivals in mind (cf. Nu. 521–4).

12 The classic discussion of the character of the Aristophanic hero remains Whitman, C. H., Aristophanes and the Comic Hero (Martin Classical Lectures, 19) (Cambridge, MA, 1964CrossRefGoogle Scholar). On the names of Aristophanic heroes and how they are used in the plays, see Barton, A., The Names of Comedy (Toronto and Buffalo, 1990), pp. 13–27, esp. 22–7.Google Scholar

It seems to be a basic convention of Aristophanic comedy that the first free character to appear and speak onstage is ‘the hero’ (Dicaeopolis in Ach., the Sausage-seller in Eq., Trygaeus in Pax, Strepsiades in Nu., Lysistrata in Lys., Praxagora in Ec, Chremylus in Pl). When two free characters appear more or less simultaneously, V., Av., Th.) the lead is split, at least initially, but one character eventually emerges as dominant (Philocleon in V., Peisetairos in Av., ‘In-law’ in Th.).

13 There is remarkable emphasis on the women's names throughout the opening scenes of Lysistrata; the heroine, for example, is named not only at 6, but also at 21, 69, 135, 186, 189, 216. This may be in part an attempt to increase the voyeuristic character of the opening action by offering a glimpse of ‘how women really talk among themselves’, for the names of respectable women not holding public office were normally not mentioned in public by free men unrelated to them (see Schaps, D., ‘The Woman Least Mentioned: Etiquette and Women's Names’, CQ 27 (1977), 323–30CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Sommerstein, A. H., ‘The Naming of Women in Greek and Roman Comedy’, Quaderni di storia 11 (1980), 393–418Google Scholar; Bremmer, J., ‘Plutarch and the Naming of Greek Women’, AJP 102 (1981), 425–6)Google Scholar. We may also see here an emphatic effort on the playwright's part either to associate his heroine with Lysimache, priestess of Athena Polias, who may have been well known as an advocate of peace (cf. Pax 991–2; Lys. 554) or simply to bring the most significant aspect of Lysistrata's character out into the open as soon as possible. The question is discussed by Henderson (n. 2), pp. xxxvi–xli, who argues it is probably significant that Lysistrata is never named by a man until the success of her scheme is assured (p. xl). The situation in Frogs is somewhat more straightforward and probably reflects the fact that Dionysus is a god and oddly costumed; see ‘Gods’ below and n. 38. The artlessness with which Dionysus reveals his name may also represent a comment on his lack of substantial qualifications to be a comic hero.

14 For a different perspective on Dicaeopolis' name and its meaning, see Bowie, E. L., ‘Who is Dicaeopolis?’, JHS 108 (1988), 183–5CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and the response of Parker, L. P. E., ‘Dicaeopolis or Eupolis?’, JHS 111 (1991) 203–8.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

15 Thus the heroes in Acharnians, Knights, Peace, Clouds and Birds all identify themselves fname for the first time specifically in the context of a doorkeeper scene or a visit to another character's home (Euripides' house in Ach.; Demos' house in Eq.; Zeus' house in Pax; Socrates' ThinkTank in Nu.; the Hoopoe's house in Av.). Dionysus' name is revealed at Frogs 22, just before he arrives at Heracles' house. When a minor free character is given a name and allowed to engage a previously anonymous hero or heroine in dialogue, this also seems to trigger naming of the hero (Lysistrata at Lys. 6 after naming Kalonike; the previously anonymous Chremylus at Pl. 336 after identifying Blepsidemus in an entrance announcement at 332). The reverse is not true: the heroine of Ecclesiazusae is called ‘Praxagora’ at 124, but none of the other female conspirators who appear onstage with her is ever so distinguished. In fact, there seems to be a relatively simple convention at work with characters of this sort: either they are named immediately (Kalonike at Lys. 6; Myrrhine at Lys. 70; Lampito at Lys. 77; Kinesias at Lys. 838; Blepsidemus at Pl. 332), or they are never named at all (esp. the women in Ec. and Th.). The sole exception (except for real Athenians parodied onstage, for whom different conventions apply; see below) is Chremes, who appears as an anonymous character at Ec. 372 and receives a name at the moment he exits (Ec. All). This is extremely odd, and suggests he is being marked out as a character who will reappear again later on in the play, in this case as the otherwise anonymous Master (Ec. 1128); cf. Olson, S. D., ‘Anonymous Male Parts in Aristophanes' Ecclesiazusae and the Identity of the Despotes‘, CQ 41 (1991), 36–40, esp. 39–40.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

16 Dicaeopolis clearly has the advantage here since he knows his opponent's name. He therefore uses it repeatedly (Ach. 575, 578, 614, 619) and ultimately puts it to good service by expressly barring Lamachus from the New Agora (Ach. 625, cf. 722). Compare the behaviour of the hero in Peace, who eventually gives his name when asked (Pax 188–91) but only after showing his contempt for Hermes' bluster by mockingly identifying himself as Μιαρώτατος son of Μιαρώτατος (Pax 185–7).

17 On the power of names and ‘name-magic’ in Greek literature, see Brown, C. S., ‘Odysseus and Polyphemus: The Name and the Curse’, CompLit 18 (1966), 193–202Google Scholar; Austin, N., ‘Name Magic in the Odyssey’, CSCA 5 (1972), 1–19Google Scholar; Peradotto, J., Man in the Middle Voice: Name and Narration in the Odyssey (Martin Classical Lectures New Series, 1) (Princeton, 1990), esp. pp. 94–170Google Scholar. As a direct result of the power they represent, names are used on a routine basis in dialogue for emphasis or to attract the notice of another character (e.g. Eq. 769, 773, 850, 1152, 1173, 1261; V. 163; Nu. 827; Lys. 9, 135, 186, 189, 216, 1147; Th. 193; Ra. 1220, 1268, 1272; Ec. 124, 241; Pl. 344) as well as in the context of (often desperate) pleas, requests or offers (e.g. Eq. 747, 820, 905, 910, 1207; Pax 1203; Nu. 256, 736, 784; Lys. 746, 872, 874, 906; Th. 177, 218, 249, 634; Pl. 230); even initial greetings are sometimes combined with requests (Ach. 959–62, 1048–53, 1085–8; Eq. 147–8, 725–6; Nu. 80–1, 218–19, 221–4, 866–7) or complaints (Ec. 520). Obsequious flatterers also have a strong tendency to use vocatives when addressing their victims (esp. Eq. 47–52, 1341–2; cf. 725–6, 732, 747, 769, 773, 777, 820, 905, 910, 1111, 1152, 1173, 1207, 1261; note also Pl. 230, 786), while legal summonses are made if possible specifically by name (Nu. 1221; Av. 1046; contrast V. 1406–8, 1417–18).

18 Cf. Barton (n. 12), p. 27.

19 On tragic slaves and the ‘dramatic grammar’ that determines their behaviour, see Taplin (n. 1), pp. 79–80; Bain, D., Masters, Servants and Orders in Greek Tragedy (Manchester, 1981)Google Scholar. On ancient slavery and modern approaches to it, see Klees, H., Herren und Sklaven: Die Sklaverei im oikonomischen und poelitischen Schriftlum der Griechen in klassischer Zeit (Forschungen zur Antiken Sklaverei, 6) (Wiesbaden, 1975), pp. 37–55Google Scholar; Brockmeyer, N., Antike Sklaverei (Ertraege der Forschung, 116) (Darmstadt, 1979Google Scholar); Finley, M. I., Ancient Slavery and Modem Ideology (London, 1980).Google Scholar

20 This character is perhaps to be identified with the mute Manodoros at Av. 657.

21 Th. 280–1 is in part an appreciative comment on the sights at the festival but the verb is an imperative and thus formally merely another command.

22 The character who accompanies the Boeotian trader onstage at Ach. 860 would naturally be taken as another mute slave were it not that his name (‘Ismenia/Ismenichos’ – Ach. 861, 954) is the male equivalent of the one assigned the previously anonymous free Boeotian ambassadress (Lys. 85–9) at Lys. 697. Some degree of identification between the first slave in Knights and the Athenian general Demosthenes is hinted at in 54–7 but the character is not given a name and thus remains anonymous. For a different perspective on the question, see Sommerstein, A. H., ‘Notes on Aristophanes' Knights’, CQ 30 (1980), 46–7.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

23 There is no textual basis for calling this character ‘Cephisophon’ as do Hall and Geldart (following an ancient scholiast to R.); compare the remarks of Coulon (n. 2), p. xxxi. The real Cephisophon was certainly free and probably an Athenian citizen; cf. the remarks of Halliwell, S., ‘Ancient Interpretations of ⋯νομαστ⋯ κωμῳδεῖν in Aristophanes’, CQ 34 (1984), 85–6CrossRefGoogle Scholar. The character who brings Dicaeopolis food from a marriage feast and requests a bit of peace in return at Ach. 1048–53 is also probably an anonymous servant. Certainly the text gives no reason to believe he is a Best Man, as Hall and Geldart would have it. The woman who accompanies him onstage, on the other hand, is a brideswoman (Ach. 1056–7) and therefore free.

24 It is possible that this slave is one of the two who open the play but it is impossible to deduce this from the text and may have been impossible to tell onstage. Servile anonymity, that is to say, may have been reinforced on the level of costuming and masks as well. For a discussion of the (not very abundant or revealing) evidence for how Aristophanes' slaves were costumed, see Stone, L. M., Costume in Aristophanic Poetry (Salem, 1984), pp. 282–5.Google Scholar

25 Dover, K. J., Aristophanes: Clouds (Oxford, 1968), ad 133CrossRefGoogle Scholar, argues that this character is a student rather than a slave. There is no explicit indication of this in the dialogue, however, so that the original audience would have been as confused about the question as we are. Contra Dover, the fact that this character is apparently acquainted with ‘Socratic’ philosophy and speaks in an abusive manner proves nothing, since Aristophanic doorkeepers regularly talk and act in ways that reflect their masters' characters and interests (Euripides' sophistically wise and quibbling doorkeeper at Ach. 395–402, esp. 398–401; Zeus' initially abusive but actually craven doorkeeper Hermes at Pax 180–233; Agathon's musical and apparently effeminate [Th. 59–62] doorkeeper at Th. 39–70). It is thus better to regard the doorkeeper in Clouds as a slave rather than a student, particularly since a separate group of real students is brought onstage at Nu. 184–99. (That Socrates himself answers the door at Nu. 1145 proves nothing more than that Aristophanes was not interested in presenting a second doorkeeper scene in the play.) Compare the remarks of Landfester, M., ‘Beobachtungen zu den Wolken des Aristophanes’, Mnemosyne 28 (1975), 384–6.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

26 If someone other than Xanthias speaks Wasps 458 or 460, this character should be added to our list, but see MacDowell ad loc. For Kudoimos and Hermes in Peace, both of whom are hybrid characters and only secondarily slaves, see the discussions below (‘Symbolic Characters’ and ‘Gods’, respectively).

27 Part of the point of the naming here may also be to mark these characters out as servile from the very beginning of the play, since the most regular male slave-name in Aristophanic comedy is in fact Xanthias (Ach. 243; Nu. 1485; V. 1; Av. 656; Ra. 271). That this is what Dionysus' servant in Frogs is called thus takes away some of his otherwise undeniable individuality. Manes (technically an ethnic) is the name of only two onstage characters (Av. 1311, 1329; Lys. 908) but is also used three times for servants mentioned in passing (Pax 1146–8; Av. 523; Lys. 1211–12; cf. Henderson [n. 2], ad loc). Mania, the feminine form of the name, occurs at Th. 728, 739, 754 (all references to a single character); cf. Frogs 1345 (supposedly an imitation of tragedy). The most common name assigned female slaves is Thratta (another ethnic) (Th. 279; cf. Ach. 273; V. 828; Pax 1138).

28 At the beginning of the play the slaves do speak of their master by name, but only behind his back and in large part in order to help the audience identify the individual who speaks 136 (V. 134, 137). Xanthias apparently addresses Philocleon by name at V. 163, but the old man is no longer his δεσπ⋯της (V. 67–9) and therefore no longer entitled to the sort of respect Bdelycleon receives (cf. V. 439–51). For masters addressed as δ⋯σποτα, cf. Pax. 257, 875; Ra. 1, 272, 301; Pl. 67.

29 On this character and his significance in the play, see most recently Olson, S. D., ‘Cario and the New World of Aristophanes' Plutus’;, TAPA 119 (1989), 193–9.Google Scholar

30 Compare the way in which the Paphlagonian slave in Knights repeatedly addresses his master as ‘Demos’ (e.g. Eq. 725, 773, 905; cf. 50), thus showing exactly how tenuous the old man's control over his household really is.

31 Messengers and heralds are different sorts of characters. Messengers bring news to particular individuals (Ach. 1069–77, esp. 1073–4, 1084–94, esp. 1085–8; Av. 1121–63, esp. 1122–4, 1168–85). Heralds either make or are on their way to make public proclamations (Ach. 1000–2; Av. 1269–75; Lys. 980–1012; Ec. 834–52; cf. Av. 448–50), or are involved in the official functions of the Assembly (Ach. 43–173; Th. 295–311, 372–9). They are therefore not announced. The character at Birds 1706–19, designated ῎Αγγελος in the Hall and Geldart text, is thus actually a herald. For the complexities that surround messengers in tragedy, see Taplin (n. 1), pp. 81–5.

32 The return of the newly healed (Pl. 738) Wealth at Pl. 771 is carefully prepared for and announced by the Wife's question and Cario's extended response at 749–59 (cf. Pl 767). Presumably Wealth's physical appearance has changed as a result of his experiences in the Asclepieion and the poet wants to make sure he is recognized when he enters. On the costuming in this play and its significance, see Groton, A. H., ‘Wreathes and Rags in Aristophanes' Plutus’, CJ 86 (1990), 16–22.Google Scholar

33 For the physical appearance of Aristophanic gods onstage, see Stone (n. 24), pp. 309–40, to whose arguments and conclusions I refer frequently below.

34 He and Dionysus do address one another repeatedly as ‘brother’ (Ra. 58, 60, 164), and Dionysus names him outright later on (Ra. 282).

35 Thus also Stone (n. 24), pp. 316–20.

36 Stone (n. 24), pp. 327–8, argues (although without explicit textual support) that Pluto carries a cornucopia with him when he enters. It is unclear whether the god enters at ca. 830 and then sits mute for almost 600 lines until 1414 (Stanford, W. B., Aristophanes: The Frogs (London, 1958Google Scholar), or whether he instead comes onstage somewhere around 1410, which would require postulating a lacuna in the text (MacDowell, D., ‘Aristophanes' Frogs 1407–67’, CQ 9 [1959], 261–8).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

37 Stone (n. 24), p. 329.

38 It may well be the similarly confusing mixture of his own iconography with that of Heracles (Ra. 46–7, cf. 108–9) which forces Dionysus to give his name at Frogs 22.

39 Stone (n. 24), pp. 311, 335–6 n. 5, on the other hand, argues that Charon is immediately recognizable to the audience and that the humour here depends on the fact that Dionysus ‘is ridiculously unaware of everything connected with the underworld’.

40 Cf. Birds 572–5, where Peisetairos' remark points to the fact that many of the gods match the sketchy description the Messenger gives of the divine interloper (Av. 1171–7), and the remarks of Stone (n. 24), pp. 320–2.

41 The evidence for Prometheus' iconography is discussed at length by Beazley, J. D., ‘Prometheus Fire-lighter’, AJA 43 (1939), 618–39CrossRefGoogle Scholar; a summary is given by Stone (n. 24), pp. 330–2.

42 I trust it is clear that what follows is not an attempt to offer an updated prosopography of Athenians in Aristophanes; a full-length study of the problem by I. C. Storey is forthcoming. On the caution with which Comic slanders must be treated, cf. Halliwell (n. 23), pp. 83–8.

43 Given this very clear overall pattern, it seems likely that Nicarchos (PA 10718), who appears onstage at Ach. 910 after having been named at 908, is a real (but otherwise unattested) Athenian citizen. The name of the deceptive Persian ambassador Pseudartabas (‘False Measure’) (Ach. 91, 99), on the other hand, is obviously just a joke, as is that of the abusive inn-keeper Plathane (< πλ⋯θανον, ‘bread-pan’) at Frogs 549; compare four members of the Chorus of charcoal-bearers in Acharnians, named Marilade (‘Coal-dust’) (Ach. 609), Drakyllos (‘Handful of wood’?), Euphorides (‘Son of Good-carrying’) and Prinides (‘Son of Pine’) (Ach. 612). The name of the battered bread-woman Myrtia at Wasps 1388–1414 may be an obscure (sexually oriented?) pun on μ⋯ρτον, ‘myrtle-berry’; cf. Lys. 1004–5.

Characters who represent real contemporary individuals under different identities also have these secondary identities established carefully and early on. Thus the fact that the Paphlagonian slave who enters at Knights 235 represents Cleon (PA 8674) is made clear by the emphatic initial connection of him with hides and tanning (Eq. 44, 47), as well as by the description of his political practices in 46–70; note also the emphatic reminder at 230–3 that this is a symbolic figure. So too the real identity of the dog ‘Labes’ (= the general Laches [PA 9019]) in Wasps is obvious from the first, since Cleon's prosecution of Laches is mentioned early on in the play (V. 240–4) and the Sicilian origin of the cheese allegedly gobbled down is made explicit (V. 837–8) well before the two dogs actually appear onstage (ca. V. 893, 899).

44 Given that the name is very rare, it seems a reasonable assumption that this Amphitheos is to be identified with the man whose name appears in IG ii2.2343, a list of members of a thiasos of Heracles which dates from the late fifth century B.c. and includes a number of other individuals associated with Aristophanes; cf. Dow, S., ‘Some Athenians in Aristophanes’, AJA 73 (1969), 234–5Google Scholar; Welsh, D., ‘IG ii2.2343, Philonides and Aristophanes' Banqueters’, CQ 33 (1983), 51–5CrossRefGoogle Scholar. As we know nothing more about Amphitheos, however, it is difficult to understand precisely what the point of the parody in Acharnians might be. Presumably the claim to divine forebears (Ach. 46–51) is only an Aristophanic joke based on the literal meaning of the name (‘a god on both sides’).

45 On the real significance of Aristophanes' repeated attacks on Cleonymus' alleged cowardice, see Storey, I. C., ‘“The Blameless Shield” of Kleonymos’, RhM 132 (1989), 247–61.Google Scholar

46 Compare the treatment of Minor Characters (above), which this procedure largely duplicates.

47 For Derketes, see IG ii2.75.7 and 1698.6, cited by Sommerstein ad loc. There must be more to this joke (which also plays with the idea of a blind character whose name literally means ‘Seer’) than we can appreciate.

48 The same sort of humour is apparently at work in Ach. 115–22, where the two anonymous eunuchs who enter with Pseudartabas are suddenly revealed to be Cleisthenes (PA 8525) and Straton (PA 12964). On the notoriously confusing action in this scene, see most recently Chiasson, C. C., ‘Pseudartabas and his Eunuchs: Acharnians 91–122’, CP 79 (1984), 131–6Google Scholar. This sort of joke also probably helps explain the twenty-line delay in identifying the cadaverous witness brought onstage at Wasps 1388 as Chaerephon (PA 15203), whose unhealthy appearance was perhaps a matter of public comment (cf. Nu. 501–4).

49 The most important study of the problem remains Dover, K. J., ‘Portrait-Masks in Aristophanes’, in Κωμωιδοτραγ⋯ματα: Studia Aristophanea Viri Aristophanei W. J. W. Koster in Honorem (Amsterdam, 1967), pp. 16–28.Google Scholar

50 Dover (n. 49), p. 20. On the cause of Cleisthenes' beardlessness, see also Dover (n. 25), ad 355: ‘no doubt through an endocrine disorder’.

- 21

- Cited by