In Tom Dishion's conceptualization of effective interventions benefiting children, four principles were deemed critical: that they are based on theory and prior empirical evidence; that they benefit children in the context of their families; that they are pragmatic to deliver in the real world (i.e., are time-limited and cost-effective); and that there is an understanding of why or how they work, with clearly elucidated mechanisms for change (Dishion & Mauricio, Reference Dishion, Mauricio, Van Ryzin, Kumpfer, Fosco and Greenberg2015; Dishion & Stormshak, Reference Dishion and Stormshak2007; Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Shaw, Connell, Gardner, Weaver and Wilson2008). We present here preliminary evidence on Authentic Connections Virtual Groups (ACV Groups), an intervention based in contemporary priorities in the field of resilience (Goodman & Garber, Reference Goodman and Garber2017; Luthar & Eisenberg, Reference Luthar and Eisenberg2017; Taylor & Conger, Reference Taylor and Conger2017), and in prior randomized control trials by our team (Luthar, Curlee, Tye, Engelman, & Stonnington, Reference Luthar, Curlee, Tye, Engelman and Stonnington2017; see also Luthar, Suchman, & Altomare, Reference Luthar, Suchman and Altomare2007). This program was developed for mothers experiencing high everyday stress in their role as parents, along with high personal stress experienced in their role as professionals.

Specifically, there are two underlying aims pertaining to ACV Groups in this paper. First, we seek to explore the feasibility of scaling up the provision of groups via video conference sessions as opposed to meetings in person, and second, to understand the mechanisms underlying the benefits of the intervention using qualitative data. These aims are addressed in three sections. At the outset of this paper, the scientific background for this work is presented, beginning with contemporary evidence that (a) resilience among children is best fostered by ensuring the well-being of their primary caregivers (usually mothers) and (b) that the urgent need of the day is scalable interventions that reach caregivers at risk. Following this is a summary of existing empirically validated, relationally oriented interventions for mothers under high stress. Next, we describe the procedures involved in the development and implementation of the ACV Groups program, and present preliminary data from the five sets of groups conducted toward establishing the feasibility of this approach, potentially on a larger scale. The paper concludes with discussions of limitations of this study, the interface of findings with trends in contemporary theory and practice, and directions for future efforts in this area.

Milestones in Research on Childhood Resilience: Current Emphasis on Caregivers

Research on resilience in children, and how best it can be fostered, has a long history beginning over six decades ago, with notable shifts in emphases over time. In the early days of this work during the 1970s and 1980s, specific attributes of children themselves were of primary focus. It was believed that particular child characteristics (i.e., generally coping skills) were of central importance in differentiating who would and would not thrive despite adversity (Luthar & Zigler, Reference Luthar and Zigler1991; Masten, Best, & Garmezy, Reference Masten, Best and Garmezy1990). As the field continued to develop, researchers acknowledged that while characteristics of children themselves are important, they are only one part of three categories of major “vulnerability or protective processes,” with the other two encompassing aspects of the family and of the community.

The turn of the century brought suggestions that the triad of resilience processes should be reordered to put family first, followed by community and then child attributes (Luthar & Zelazo, Reference Luthar, Zelazo and Luthar2003). Conceptually, prioritizing the family made sense because parents are the most proximal to the child and have a more enduring influence compared to other adults in the child's life (e.g., teachers, who typically change annually). Placing child attributes last on the list was by no means meant to dismiss children's strengths or coping skills; rather, it was intended to emphasize that for researchers, interventionists, and policy makers, the primary focus should be on what adults (families and communities) can do to help ensure that children continue to thrive.

More recent reviews brought even more specificity in prioritizing critical protective processes, with conclusions echoing the core tenet that resilience rests, fundamentally, on relationships (Luthar, Crossman, & Small, Reference Luthar, Crossman, Small, Lerner and Lamb2015; Masten, Reference Masten2018; Ungar, Reference Ungar2012), and increasing emphasis on relationships between children and their primary caregivers in particular. According to a new report from the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM, 2019), titled Vibrant and Healthy Kids: Aligning Science, Practice and Policy to Advance Health Equity, the single most important protective factor, for children facing diverse life adversities, is a strong attachment with their primary caregivers, who are usually mothers. Secure attachments in turn rest on the primary caregivers' own well-being, which (as for children) is tied to their own receipt of ongoing support (for reviews see Luthar & Eisenberg, Reference Luthar and Eisenberg2017; Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Crossman, Small, Lerner and Lamb2015). Among mothers contending with depression and those at risk for maltreating their children, availability of reliable support (e.g., through home visiting programs or interpersonal therapeutic interventions) is associated with higher quality parent–child interactions (Goodman & Garber, Reference Goodman and Garber2017; Toth, Gravener-Davis, Guild, & Cicchetti, Reference Toth, Gravener-Davis, Guild and Cicchetti2013; Valentino, Reference Valentino2017). Among single mothers, perceived social support, and specifically, faith in a network that nurtures them, substantially contributes to women's personal well-being and positive parenting (Taylor & Conger, Reference Taylor and Conger2017). Reviewing the literature on early childhood interventions for families in poverty, Morris et al. (Reference Morris, Robinson, Hays-Grudo, Claussen, Hartwig and Treat2017) emphasized the strong protective potential of nurturing relationships for caregivers.

Toward Scalable Interventions

Among the current generation of resilience researchers, there is also a shift to work that directly informs scalable programs (see Luthar & Eisenberg, Reference Luthar and Eisenberg2017; Masten, Reference Masten2018). At the turn of the century, many urged more research on the role of biological processes in studies of resilience (e.g., Cicchetti & Curtis, Reference Cicchetti, Curtis, Cicchetti and Cohen2006; Luthar et al., Reference Luthar and Suchman2000; Masten, Reference Masten2007). Subsequently, it became apparent that the study of biological indices as outcomes is often invaluable, as findings on maltreatment and the developing brain were critical in “proving” its insidious effects (see Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1996; Cicchetti & Curtis, Reference Cicchetti, Curtis, Cicchetti and Cohen2006). As mediators and moderators to be harnessed in preventive interventions, however, the value of biological measures is less clear (see Luthar & Eisenberg, Reference Luthar and Eisenberg2017; NASEM, 2019), because findings on these (a) generally have small effect sizes, and (b) are unlikely to be applied in real-world efforts that are based in behavior change, not psychopharmacology, to foster well-being among today's most vulnerable children.

Outside research on resilience, the shift in focus toward scalable, community-based interventions is now echoed across disciplines, strikingly emphasized by pioneers in the treatment of childhood disorders. In a recent meta-analysis, for example, Weisz et al. (Reference Weisz, Kuppens, Ng, Vaughn-Coaxum, Ugueto, Eckshtain and Corteselli2019) note that despite decades of investing in still more laboratory-based treatments, the United States has not seen meaningful reductions in rates of major childhood diagnoses. This indicates the need for effective approaches that are more likely to reach large numbers of children and families in their own ecosystems. Describing his own rich career including multiple randomized controlled trials and decrying the vast numbers of people with unmet mental health needs, Kazdin (Reference Kazdin2018) emphasized that current research must focus on scalability, and reaching populations at high risk but routinely neglected. “Invariably, there is more to know and we always want better and more science. Yet it is important, at least for me, to keep in mind that the most common intervention for mental disorders is no treatment … (and) I am shifting my own priorities to ways of reaching people in need of services and practices that can be scaled” (Kazdin, Reference Kazdin2018, p. 646).

In public discourse and policy recommendations, similarly, the terms toxic stress and adverse childhood experiences (including aspects of maltreatment and serious parental disturbance) have become common, with associated exhortation for prevention. “As many as 34 million children are at risk of toxic stress nationwide. … Without intervention or buffering from a caring adult, toxic stress can (increase) the risk for seven of the ten leading causes of death in the United States” (Yusuf, Reference Yusuf2019). Similarly, the Vibrant and Healthy Kids report (NASEM, 2019) specifically highlights the need for community-based solutions that can be taken to a large scale toward promoting health equity in the United States.

Interventions With Mothers Under Stress

Despite the unequivocal evidence of the importance of ensuring the well-being of caregivers in their communities, few interventions currently exist that deliberately consider this as their central focus. Among the first programs to explicitly target mothers’ well-being is Lieberman's seminal infant–parent psychotherapy and its extension, toddler–parent psychotherapy, in which the aim is to diminish child maltreatment by enhancing maternal sensitivity and attachment organization (e.g., see Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Toth, Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch and Toth2006; Toth, Rogosch, Manly, & Cicchetti, Reference Toth, Rogosch, Manly and Cicchetti2006). A central ingredient is high support and empathy for the mother, with acknowledgement that “the most effective interventions are not spoken but rather enacted through the therapist's empathic attitude and behavior toward the mother as well as the baby” (Lieberman & Zeanah, Reference Lieberman, Zeanah, Cassidy and Shaver1999, p. 556). Several studies have documented the benefits of infant–parent psychotherapy and toddler–parent psychotherapy for mothers across diverse settings (Lieberman, Chu, Van Horn, & Harris, Reference Lieberman, Chu, Van Horn and Harris2011; Toth et al., Reference Toth, Gravener-Davis, Guild and Cicchetti2013).

Providing warmth and respect to recipient mothers is emphasized in Dozier's Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up as well. This program seeks to change insecure early attachments by fostering caregivers’ positive qualities, including responsiveness, nurturance, and their own attachment styles (Dozier, Albus, Fisher, & Sepulveda, Reference Dozier, Albus, Fisher and Sepulveda2002). Across multiple studies, recipients have exhibited significant gains, including improved self-regulation among both children and mothers as well as improved attachment within their dyad (Bernard, Simons, & Dozier, Reference Bernard, Simons and Dozier2015; Dozier, Peloso, Lewis, Laurenceau, & Levine, Reference Dozier, Peloso, Lewis, Laurenceau and Levine2008).

Group-Based Interventions for Mothers Under Stress

While both infant–parent psychotherapy and the Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up help bolster maternal well-being, disseminating them broadly would be constrained given that the sessions are resource intensive and developed for individual mother–child dyads. This suggests the value of empirically validated short-term group-based interventions for vulnerable mothers (Valentino, Reference Valentino2017). One such program is the Relational Psychotherapy Mothers Group program (RPMG; Luthar & Suchman, Reference Luthar and Suchman2000; Luthar, Suchman, & Altomare, Reference Luthar, Suchman and Altomare2007), a supportive, 6-month intervention developed for low-income mothers with histories of substance abuse. In two clinical trials, mothers receiving RPMG showed better personal adjustment than comparison groups, as well as decreased risk for child maladjustment (by parent and child report), and lower drug use based on urinalyses (Luthar & Suchman, Reference Luthar and Suchman2000; Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Suchman and Altomare2007). At 6-month follow-up, however, the magnitude of gains was markedly reduced. While demonstrating the benefits of taking a short-term, group-based approach, these findings underscored the importance of sustained support networks for recipients, in order to help them maintain gains achieved during the intervention phase (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Suchman and Altomare2007).

Ensuring continued supports for mothers after program completion was a central, if not a defining, component of the Authentic Connections Groups (AC Groups) intervention (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Curlee, Tye, Engelman and Stonnington2017), that was based on RPMG. AC Groups were designed to foster wellness among professional women facing high everyday stress, both in their roles at work and as parents. While session topics and strategies are similar to those in RPMG, the AC Groups program deliberately focuses on crystallizing strong relationships among mothers, not only among the group members, but also with others in their everyday lives. From early on in the program, members are encouraged to form and develop their own “go-to committees,” groups of 2 to 3 women who provide them with comfort during times of stress, as well as constructive suggestions as needed or appropriate. Another difference is program duration; whereas RPMG involved meeting for 1.5 hr every week for 6 months, AC Groups meet for 1 hr per week across 3 months. The shorter timeline was expected to suffice given the absence of serious risks (including poverty, addiction, and often other comorbid disorders) in the lives of the well-educated women, plus their greater personal, social, and financial resources.

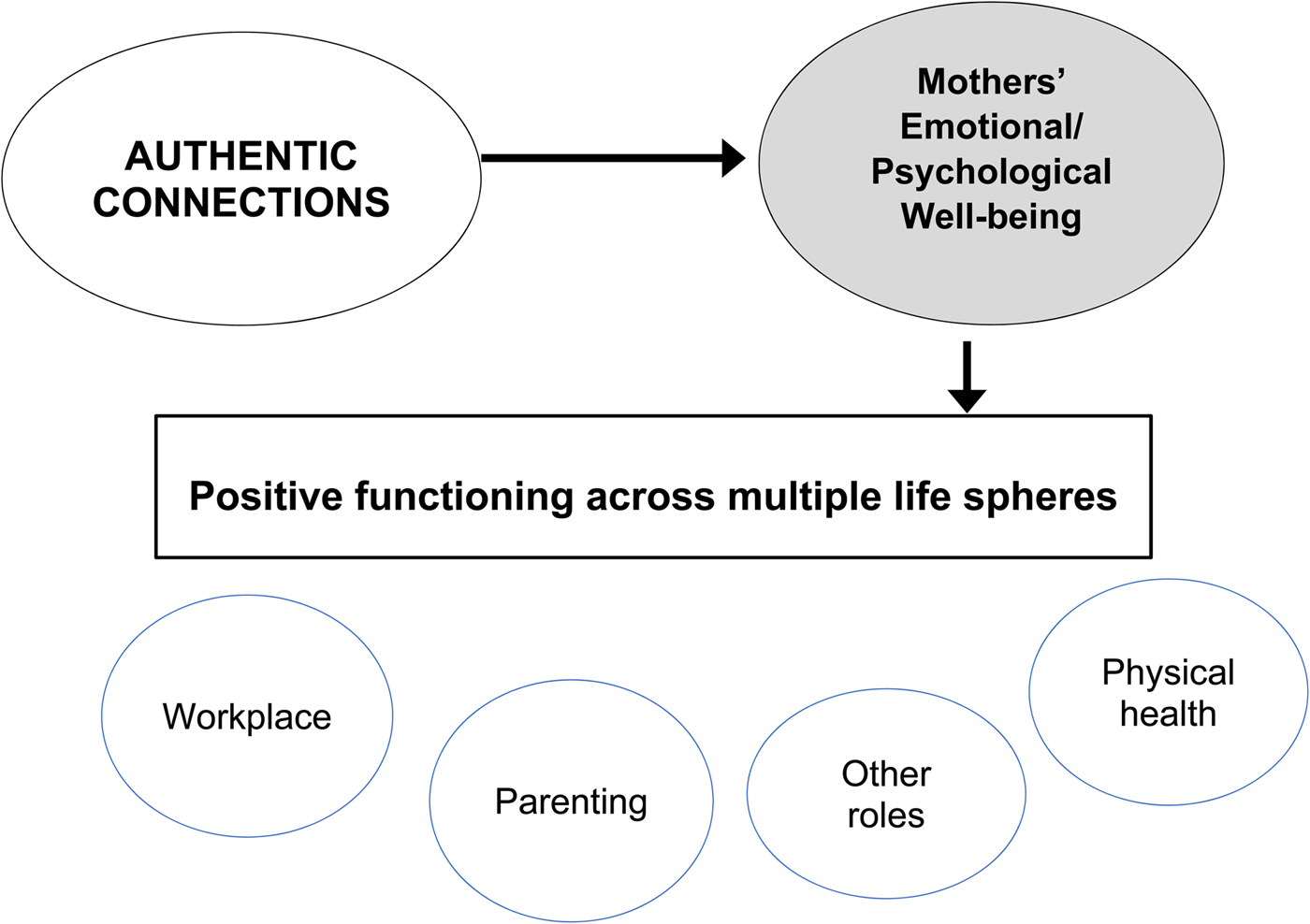

In terms of conceptual underpinnings, the AC Groups (like the more intensive, psychotherapeutic RPMG program) is based squarely in principles of interpersonal psychotherapy (Klerman, Weissman, Rounsaville, & Chevron, Reference Klerman, Weissman, Rounsaville and Chevron1984). Close, dependable relationships are viewed as integral to women's psychological well-being. Good psychological health, in turn, has spillover benefits for multiple aspects of their everyday roles and responsibilities, at home as well as in the workplace (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual model underlying the Authentic Connections groups intervention.

With regard to strategies used, similarly, AC Groups and RPMG share three defining features. The first is a supportive facilitators’ stance, encompassing the Rogerian constructs of warmth, empathy, and genuineness (Rogers, Reference Rogers1961). Second, in the tradition of Yalom (Reference Yalom1995), the program is offered in a group format, as people can receive much comfort when connecting with others facing similar challenges. The third defining feature is the facilitation of coping skills in everyday life, drawing upon a cognitive behavioral therapy framework. Each of the 12 sessions has a specific topic (see Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Curlee, Tye, Engelman and Stonnington2017), and discussions include optimal approaches to handling the issues of the day. To illustrate, sessions address ways to minimize “piling” (or rumination); dealing with anger constructively (reframing; recognizing underlying hurt); and obstacles to connecting authentically (pinpointing one's own fears about reaching out).

From a developmental standpoint, AC Groups are designed to accommodate mothers with children of all ages, following the protocol used in RPMG, as this strategy had proved valuable for all. The older mothers, in sharing some of their own challenges and experiences, were gratified at being able to provide guidance or comfort to the younger women. The latter, in turn, appreciated preparation for what might lie ahead for them as parents, given the personal sharing by their older counterparts. In order to address stage-specific challenges, furthermore, specific program sessions address children's developmental capacities and needs from infancy through adolescence (e.g., on aspects of limit setting and on children's ways of receiving affection), with associated handouts for all participants.

Randomized Control Trials With Health Providers Who Are Mothers

AC Groups were first evaluated with a sample of women known well to be at high risk for stress and burnout: health care providers who are mothers (Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Griffith, DeCastro, Stewart, Ubel and Jagsi2014). Physicians in general are at high risk for depression, with relative risks of suicide up to three times higher than the general population among male physicians and almost six times higher among females (Hawton, Clements, Sakarovitch, Simkin, & Deeks, Reference Hawton, Clements, Sakarovitch, Simkin and Deeks2001; Lindeman, Laara, Hakko, & Lonnqvist, Reference Lindeman, Laara, Hakko and Lonnqvist1996). The higher risks among women are likely linked to their multiple caregiving responsibilities, with patients at work and with children at home. Studies have shown that among married/partnered physicians with children, women spent the equivalent of a full work day per week, more than men, on domestic activities (Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Griffith, DeCastro, Stewart, Ubel and Jagsi2014). When both partners were employed and child care arrangements disrupted, women physicians were almost three times more likely than men to take time off, increasing strains experienced at work (Dyrbye et al., Reference Dyrbye, Shanafelt, Balch, Satele, Sloan and Freischlag2011). The heightened risks for stress, depression, and burnout have led to repeated calls for interventions sensitive to the needs of health care providers who are women (DeCastro, Griffith, Ubel, Stewart, & Jagsi, Reference DeCastro, Griffith, Ubel, Stewart and Jagsi2014; Levine, Lin, Kern, Wright, & Carrese, Reference Levine, Lin, Kern, Wright and Carrese2011; Levinson, Kaufman, Clark, & Tolle, Reference Levinson, Kaufman, Clark and Tolle1991).

In view of these factors, a randomized clinical trial of the AC Groups program was conducted at the Mayo Clinic in Arizona, as part of an institutional initiative to address burnout and turnover among female physicians (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Curlee, Tye, Engelman and Stonnington2017). Forty mothers on staff, including physicians, nurse practitioners, and physicians’ assistants, were assigned to either (a) 12 weekly 1-hr sessions of protected time to attend AC Groups or (b) 12 weekly hours of protected time to be used as desired. The results of this study were positive in several respects. First, there were zero dropouts during the 12-week intervention (attendance, of course, was voluntary). Second, mothers in the AC Groups showed significantly greater gains, relative to controls, on depression and overall symptoms at postintervention. More striking, at 3 months follow-up, the magnitude of relative gains was even more pronounced; AC Groups mothers fared significantly better on almost all variables assessed, including depression, overall symptoms, self-compassion, feeling loved, parenting stress, and levels of the stress hormone, cortisol (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Curlee, Tye, Engelman and Stonnington2017). Finally, effect sizes were generally in the moderate range, with partial eta squared values of 0.08–0.19 and a median of 0.16; values of 01, .06, and .14 are typically cited as reflecting “real-world” differences that are small, medium, and large, respectively, per Cohen (Reference Cohen1988), although others have argued for slightly higher cutoffs (e.g, .083 representing medium effect sizes; see Richardson, Reference Richardson2011).

Considered against the backdrop of findings from existing behavioral interventions, the impact of the AC Groups program is perhaps still more noteworthy. For example, meta-analyses of preventive interventions for families and children typically have effect sizes that are in the small range on average (e.g., Sandler et al., Reference Sandler, Wolchik, Cruden, Mahrer, Ahn, Brincks and Brown2014; Stice, Shaw, Bohon, Marti, & Rohde, Reference Stice, Shaw, Bohon, Marti and Rohde2009). Similarly, other burnout prevention programs have yielded less robust effects. In another intervention to address physician well-being at the Mayo Clinic, for example, biweekly small-group sessions were conducted over 9 months (West et al., Reference West, Dyrbye, Rabatin, Call, Davidson, Multari and Shanafelt2014). Program participants showed more improvements than controls in dimensions of professional burnout (depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and work engagement), but groups did not differ on changes in stress, depression, job satisfaction, or quality of life.

Following the success of AC Groups program at the Mayo Clinic (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Curlee, Tye, Engelman and Stonnington2017), similar groups have been offered to several other cohorts of women. These include faculty, staff, and administrators at a boarding school, women from military families, and nursing leaders at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Again, there have been no dropouts. Findings from these subsequent in-person groups are currently being prepared for publication.

AC Virtual Groups

The success of in-person AC Groups across different settings provided impetus to increase their accessibility, and starting in 2018, pilot efforts were introduced to offer groups virtually via video conference. Once again, in the field of prevention, after a program has shown initial effectiveness, it is important to demonstrate that it can be adapted for dissemination, meaning that realistically, it can be administered broadly within communities (Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Shaw, Connell, Gardner, Weaver and Wilson2008; Sandler, Ingram, Wolchick, Tein, & Winslow, Reference Sandler, Ingram, Wolchik, Tein and Winslow2015). Although previous in-person AC Groups had all been conducted at participants’ institutions, many interested women were unable to enroll given insufficient time in their workdays for commuting to and from sessions. In addition, group facilitators often had considerable commutes to session sites, adding to overall resources required per group conducted. The decision to pilot test virtual sessions was made, therefore, in an effort to address all of these issues, with the overall aim of making AC Groups more amenable for widespread dissemination.

A second goal of these virtual pilot groups was to ascertain mechanisms underlying change over time. In intervention research, it is critically important not only to demonstrate that a given program is effective but also to understand “how” and/or “why” any beneficial changes occurred. Reviewing this topic, Hofmann and Hayes (Reference Hofmann and Hayes2018) define these underlying processes as being based in theory and associated with testable predictions (examples of possible mechanisms underlying cognitive behavioral therapy include emotion regulation, problem solving, cognitive reappraisal, and interpersonal skills). As qualitative data can be critical in understanding mechanisms underlying intervention gains (Weisz et al., Reference Weisz, Ng and Bearman2014), participants were each asked to describe how exactly the program had helped them, as well as how they might describe benefits of the program to other women.

With a core basis in the interpersonal psychotherapy approach emphasizing positive relationships, a priori expectations were that women's subjective experiences would cohere around forming supportive, dependable connections. To reiterate, a core component of the program is the crystallization of women's “go-to-committees,” so that even as they receive ongoing support in groups, they are strengthening reliable connections outside of the group as well (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Curlee, Tye, Engelman and Stonnington2017). In addition, session topics revolve around close relationships and call for some self-disclosure (e.g., shame vs. self-compassion, or contagion of our children's pain); over time, this leads to participants feeling safe in sharing confidences and in receiving genuine support from other group members.

To summarize, the aims of this study were twofold. The first aim was to determine the feasibility and potential effectiveness of AC Groups offered via video-conferencing, as opposed to in-person. Second, we sought to illuminate the mechanisms or “active ingredients” underlying the groups’ beneficial effects by obtaining qualitative data from all group members, in addition to their quantitative overall rating of the program.

Method

Overview of procedures

The AC Virtual Groups (ACV Groups) relied on the same concepts, program sessions, and themes described in the original AC Groups program (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Curlee, Tye, Engelman and Stonnington2017), but the web-based program differed from the original intervention in recruitment procedures. Rather than signing up for the groups via their employers, the women completed an intake signup form on the AC Groups website that was designed by the second author (see http://www.authenticconnectionsgroups.org/pages/acgroups.html). When possible, attempts were made to group participants based on demographic similarities (e.g., women who were all mothers of older children or adults; mothers who shared similar careers).

All virtual group meetings were run using Go-to-Meeting video conferencing software and were facilitated by the first author. Participants used their personal computers, smartphones, or tablets to join the session, with web cameras enabled to allow all participants to see everyone. To accommodate occasional immovable constraints in schedules (e.g., when groups fell on holidays), sessions were not all run over 12 consecutive weeks. While each group participated in 12 sessions overall, in some instances gaps between sessions were 2 weeks rather than 1.

To ensure the viability and robustness of each group that was formed, two ground rules were shared with interested women before they committed to participating. One was that members log in promptly on time to maximize the use of the one hour to which all had committed. The second was that (barring any emergencies, of course), they would miss no more than two of the scheduled sessions.

Participants were not charged for the groups. Aside from Group 4 (Consultants; see Table 1), which was conducted via the women's organization in a manner similar to the initial Mayo Groups (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Curlee, Tye, Engelman and Stonnington2017), all participants were invited to donate to the nonprofit that funded this project if they so wished. Women were assured that inability to contribute would by no means preclude their participation.

Table 1. Verbatim responses to the question “In what ways have you found these groups useful?”

Note: Phrases from a phrase in two responses have been removed, as they would have identified the respondents.

Informed consent procedures made it clear that AC Groups are not intended to provide psychotherapy; rather, they are support groups intended to foster authentic connections in everyday life. Outside of scheduled groups, however, the facilitator was available for occasional one-on-one phone calls with women as needed (e.g., when there was a need for follow-up from substantive issues emerging in a session, or if women had a crisis that required help finding additional professional assistance).

Sample

Reported here are results from five ACV Groups. Two groups included women who had never met before (labeled Moms-1 and Moms-2; n’s 3 and 5, respectively), while three groups (1, 2, and 4 [pediatricians, psychologists, and consultants]; n’s 4, 5 and 6, respectively) included women who currently or had previously worked together professionally. The total n across groups was 23. The first two groups started in April 2018, and the other three, in order, began in May, July, and October 2018.

With regard to demographic characteristics, the women ranged in age from 31 to 52 years, with a mean of 40.4 (SD = 6.5). Across groups, all had higher educational degrees with 13, 4, and 6 women, respectively, having doctoral, masters’, and bachelors’ degrees. Most participants were married or in committed relationships (n = 18). In three groups, all participants were mothers, whereas in two groups (psychologists and consultants), two members did not have children. Twenty-two of the 23 participants were employed outside the home.

It should be noted that one of the earliest ACV Groups that started in June 2018 is not reported here because it was cancelled. After a few sessions, it was clear that meeting on a regular basis as a group was not feasible. For one thing, two of the five enrolled women had major changes in their jobs, which prohibited regular attendance of groups; in addition, given that summer was impending, another woman anticipated additional absences given child care issues. For these reasons, this group was discontinued, but the facilitator remained accessible to the remaining women on a biweekly basis for 3 months, as promised.

Following the aforementioned events with this one group, enrolment procedures were altered to ensure that women more clearly understood what they were signing up for. After initial contact on the website, women were asked to complete an intake form describing briefly why they were drawn to the program, which helped sort out those who potentially had just a passing interest. Following this, a welcome letter reiterated the previously noted ground rules of missing no more than 2 of the 12 sessions in order to maintain the groups’ cohesiveness, and to ensure that all group members gained maximum benefits from participation.

Measures

To gather quantitative feedback about group satisfaction, participants were asked, “On a scale from 1 to 10, how likely are you to recommend these groups to a friend or colleague?” Qualitative data were obtained via the following questions: “In what ways have you found these groups helpful?” and “If you were to recommend these groups to a friend or colleague, how would you describe their value?” Participants were also asked if they had any suggestions for improvement. All responses, quantitative and qualitative, remained anonymous.

Results

With regard to the quantitative ratings, participants were very likely to recommend the groups to others. Across the 23 participants, the mean rating on a scale of 1 to 10 was of 9.61, (SD = 0.83). Three of the groups had scores of 10/10 from all the participants: the psychologists group, as well as both of the moms groups. Individual rating scores from the pediatricians were 10, 10, 9, 8, and from the consultants were 10, 10, 10, 9, 8, 7.

As is done by other offerings to assess loyalty of service recipients, we also computed the “Net Promoter Score” (NPS; Medallia, Reference Medallia2019) based on responses to likelihood of recommending the program. In general, raters who give a 6 or below to this question are considered detractors (i.e., likely to take away from the spread of the service), those giving a score of 7 or 8 are passives (not likely to contribute to or take away from the spread of the service), and those giving a 9 or 10 are promoters (likely to contribute to the spread of the service). NPS is calculated as the percentage of detractors subtracted from the percentage of promoters; with a possible range of –100 to +100, a score over zero is considered “good,” over 50 is “excellent,” and above 70, “world class” (Yan, Reference Yan2019). The NPS of the ACV Groups was 20/23–0 = 87%, which falls well above the cutoff for “world class.”

With regard to qualitative data, presented in Tables 1 and 2 are participants’ verbatim responses to the two questions about perceived value of the groups. In discussions that follow, we note respondents’ group number-participant number, and table number (T1 or T2). As an example, “2-3, T2” would represent a response from the second group's third participant, located in Table 2.

Table 2. Verbatim responses to the question “If you were to recommend these groups to friends or colleagues, how would you describe their value?”

As expected, responses from several women highlighted authentic connections with others as a critical aspect of these groups. For example, women noted that it was helpful to connect with others who understood them, shared their concerns, or that they “really matter” (2-1, 2-5 T1; 2-2, 3-2 T2). One noted that “each member [in the group] actively listens to one another and cares what every woman has to contribute” (2-3, T1), as another noted that “finding that you can create real connection in such a short time is … eye opening” (5-5; T1). Described benefits of the program included being “cared for” (1-2, T2), receiving personal validation (1-1, 1-3; T1), and connecting with others going through similar experiences (2-5, 3-2 T1; 2-4 T2). The groups also allowed participants to receive “support and love from other women” (3-2; T1), and made some women feel less alone (4-2, 4-6, T1). Some who participated in groups at work said they were able to form lasting friendships with their colleagues (4-1, 4-2, 4-3, T1).

Results also showed that several participants reported feelings of safety, comfort, and even unconditional love, from others in the group. For example, women noted that groups provided a nonjudgmental and safe space to be vulnerable, honest, and at ease (2-3, 2-4, 2-5, 3-1, 3-2, 4-5, T2). Some noted that participating in the groups taught them to get support from others in times of need (1-1, 1-2, 2-3 T1; 5-1 T2). With regard to unconditional acceptance, one participant noted that she felt “honesty, compassion, and love … from each member of [the] group” (2-3; T1). Other relevant responses included that the groups provided “a feeling of belonging and love” (5-3 T2) and “unconditional acceptance” (2-5, T1); that each woman was “accepted and loved for who she is at her core” (3-2; T2) and that, “I found women, who I would have otherwise never known, who see me and who I adore.… They provide a sense of belonging and love” (5-3; T1, T2).

Participants’ suggestions for program improvement

We also asked participants, “Do you have any suggestions on how we can improve AC Groups?” and responses reflected no consistent themes; the responses were also brief, and therefore are summarized here rather than presented in a table. The most common response, from 11 women, was that they had no suggestions. Three women suggested having some sort of in-person meeting to accompany the virtual sessions, and 2 said they would want more sessions or over a longer period of time; this reflected the general feeling expressed during groups that the women did not want the 12-session program to end (at the time of this writing, most of them have continued to meet on a biweekly or monthly basis). The remainder of suggestions were each expressed by only 1 woman of the 23 (e.g., sharing session topics at the start of the program or not having sessions in the middle of the workday), thus highlighting a few women's personal preferences rather than a recurrent theme among more than 1 participant.

Discussion

Results of this effort to pilot ACV Groups were encouraging at several levels. Quantitatively, the women averaged 9.6/10 in ratings of how likely they were to recommend the program to others like them. Qualitatively, their open-ended responses indicated that critical dimensions of positive relationships were changed via the program. From a pragmatic perspective, the use of a virtual (as opposed to in-person) format for meetings had (a) made it much easier for women to attend the sessions, and at the same time (b) apparently sacrificed little with regard to intimacy among the women, as is discussed further in discussions that follow.

Quantitative ratings

The overall ratings across the five groups were high, with a mean score of 9.6 of 10 and no group having an average score below 9. Eighteen of the 23 women, or 78% of all participants, gave a score of 10 out 10. In addition, the NPS—an index of the proportion of recipients who are highly enthusiastic about the program versus those with poor ratings—was 87, which falls in the exceptionally high range (Yan, Reference Yan2019). These values indicate that, overall, participants of the ACV Groups were very satisfied with their experience and would be highly likely to recommend ACV Groups to others.

The two lowest ratings of 7 and 8 both came from the group of management consultants. This could be a result of various factors, all of which might merit consideration for future work. First, of the six women in this group, only two were not mothers. In general, issues discussed in sessions seemed to resonate more readily with the women who were mothers. Although plausible, this explanation is not supported by data from the other ACV Group that also included women without children (in Group 2, psychologists, in those who were not mothers, ratings were unequivocally positive across all participants).

A second possibility is that there could have been reservations about the level of intimacy that is called for in AC Groups. In general, some people prefer to share personal issues with friends and family and not with colleagues with whom they interact at work. Admittedly, the four pediatricians in Group 1 also worked in the same hospital (as had the health care providers in the original trial); however, the nature of consulting work could partially explain differences in findings. Management consultancy calls for excellent analytic skills and productivity but not necessarily for connectedness with others, as is an important part of working in health care.

Regardless of the reasons for the lower rating of the consultants’ group overall, their feedback provides valuable directions for future work. In new efforts targeting wellness in the workplace, it could be helpful to place women in groups with those whom they do not directly work with or supervise. In addition, it will be important to be make it explicitly clear to women interested in joining that this program does involve self-disclosure. Sessions are not intended to elicit discussions of any deeply traumatic issues (these subjects are deliberately avoided) but sharing areas of personal vulnerability is integral to this intervention; it is this very sharing that help to forge authentic connections, as evident by the open-ended responses discussed next.

Qualitative ratings: Relational themes

Overall, participant responses indicate that the groups were successful at creating and strengthening supportive connections. In response to the questions asking how they had found the groups useful, and how they would explain their value to others, there were recurring references to positive dimensions of relationships known to be critical for the well-being of mothers (Ciciolla & Luthar, Reference Ciciolla and Luthar2019; Luthar & Ciciolla, Reference Luthar and Ciciolla2015). Women's responses reflected multiple facets of the following broad dimensions: appreciating the strong, supportive connections forged and bonding around shared challenges, and feeling that they could safely let down their guard and be their “real” selves, receiving unconditional acceptance from others like them.

Aside from these themes, one emerged that was not anticipated: several women appreciated that these groups essentially “enforced” the formation of authentic connections. As noted earlier, almost all these participants were in high-pressure careers, and the myriad demands of their everyday work and home lives meant that they did not typically ensure regular connections with supportive friends. Thus, a major benefit of being in this program was this prescribed connectedness, as seen in several statements: being “held accountable” for making connections, “accountability for building a network of support,” having a “dedicated time” to connect with others and a “weekly commitment to listen and be heard in an intimate setting,” and enforcing “connection with others and forming meaningful bonds.”

It should be noted that the video conferencing format clearly did enhance women's attendance at groups despite multiple obligations in very full days. To illustrate, there were several instances where women joined from hotel rooms while at conferences, from their cars, while waiting for their children's after-school activities to be completed, or from their homes with newborn babies. For these women, attending their groups became a high priority, and they attended one way or another if at all possible, something they may not have been able to do if they were constrained by meeting at a specific in-person location.

It is also worth noting that an active ingredient of this program is the ready support of the women for each other, as much as if not more so than direct support from the facilitator (few open-ended responses even mentioned bonds with the facilitator). Past the first couple of sessions, any woman's sharing of a difficult, painful experience was immediately met with expressions of genuine concern and caring (spoken or nonverbal) from all other attending women. There was palpable healing in these exchanges, coming as they did, spontaneously and genuinely, from “real people” (as opposed to a professional or clinician). As Emmy Werner (Reference Werner, Meisels and Shonkoff1990) showed early in her classic longitudinal study on resilience, good therapy is beneficial, but nothing heals like love in real life.

Growing connections among mothers in their communities

Another point warranting emphasis is that aside from their weekly sessions over 3 months, members in all of the groups came to connect outside of their program sessions, in person and/or via text or phone calls. For example, the pediatricians had an in-person “Authentic Connections Groups party” about halfway through the 3 months, while the Moms-1 group, composed of participants from three different states, scheduled a trip where they met up in person. All groups created electronic communication “threads” via email or text message. In addition, in all five groups, women spoke, during sessions, of times when they had reached out to another group member when in crisis or distress, and had received a great deal of support. This sort of reliable, mutual support from others in their everyday lives is critical for mothers under stress, as is now recurrently highlighted in resilience research (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar and Ciciolla2015; Luthar & Eisenberg, Reference Luthar and Eisenberg2017), and is front and center in policy recommendations to maximize equity of well-being among children (NASEM, 2019).

The present findings also resonate with increasing endorsements of nontraditional ways to provide services to people, using modes other than clinic-based child or family therapy and drawing upon existing resources (see Kazdin, Reference Kazdin2018; Rotheram-Borus, Swendeman, & Chorpita, Reference Rotheram-Borus, Swendeman and Chorpita2012; Weisz et al., Reference Weisz, Kuppens, Ng, Vaughn-Coaxum, Ugueto, Eckshtain and Corteselli2019). There is now extensive evidence, for example, that lay individuals can be trained to administer evidence-based treatments and deliver these just as effectively as mental health professionals (see Kazdin Reference Kazdin2018; Luthar et al., Reference Luthar and Ciciolla2015). The benefits of support from others like oneself is also highlighted in life span developmental research, wherein neighborhood residents are helped to create mutually supportive behaviors and thus to attain positive physical and psychological well-being (Antonucci, Arouch, & Birditt, Reference Antonucci, Arouch and Birditt2014).

In future scalable interventions for mothers, specifically, the NASEM (2019) report calls for greater use of supportive group-based programs such as RPMG and AC Groups (virtual or in-person); also highlighted is promising new model, the MOMS (Mental Health Outreach for MotherS) Partnership (Smith, Callinan, Posner, Ciargello, & Holmes, Reference Smith, Callinan, Posner, Ciargello and Holmesin press). This innovative intervention targets low-income mothers at risk for depression with groups meeting in their community supermarkets (McMickens et al., Reference McMickens, Clayton, Rosenthal, Wallace, Howell, Bell and Smith2019). Trained mothers from the local area, who are uniquely able to develop authentic partnerships with other women, work on outreach, retention, and treatment alongside traditional licensed mental health clinicians. Thus, this intervention provides a nonstigmatized, easily accessible way for women to get help for distress, with one participant stating, “Well, it's in the neighborhood, you know what I'm saying? … It's easy for people to get to. Easy access.” (McMickens et al., Reference McMickens, Clayton, Rosenthal, Wallace, Howell, Bell and Smith2019, p. 482). Benefits of the mutually supportive group format were noted, with the program described “as a way of bonding with other mothers and relieving isolation.” Participating mothers in these particular groups also appreciated the modeling of authentic connections by the facilitators, appreciating their strength as well as caring, or in the words of one mother, “their softer side. So, you see that you can be a strong woman that you want to be and that you can still have that kindness and that sweetness” (McMickens et al., Reference McMickens, Clayton, Rosenthal, Wallace, Howell, Bell and Smith2019, p. 483). In the years ahead, there is potential for a similar model for ACV Groups, as many “graduates” are clearly able to facilitate groups themselves, and with some appropriate training and supervision, could help grow the spread of the program and reach large numbers of women greatly needing support.

Limitations and future directions

In weighing the persuasiveness of these findings, obviously, the small sample size is a major limitation; yet, other factors might somewhat attenuate concerns on this front. Most important, there was 100% retention across the 3-month program. This is extremely rare in prevention science. In addition, all the women were “informed consumers”; other than the consultants, all the women had graduate degrees themselves in child development, medicine, education, and social policy (and many were clinicians themselves). The combined facts that these women stayed through completion of the program; that their ratings were close to perfection; and that most wanted to continue groups (and did so) is testimony to both the need for, and effectiveness of, such support groups. (Note: At the time of this writing, a sixth virtual group was successfully completed with 5 more mothers, bringing the total n of ACV Groups completers to 28, still no dropouts, and evaluations similar to those detailed here.)

A second limitation is that the women had self-selected to participate in these groups. It is possible that this program may not be successful for all women, but only for those already possessing a belief that strong connections foster well-being. Third, some groups contained women who had known each other prior to the start of the intervention, which could have inflated their propensity to form strong connections with one another. At the same time, several women in the two groups that brought together strangers (Moms-1 and Moms-2) said that they would have found it more difficult to self-disclose had their groups included colleagues with whom they interacted at work, and that being with strangers was preferable for them.

As participants in this study were all well-educated women, generalizability of effects cannot be assumed, and in future efforts there is value in testing this intervention with diverse samples. In theory, ACV Groups could be accessed by a large percentage of mothers of lower socioeconomic status as well, as it is possible to join with just a smartphone (i.e., computers are not essential). In addition, it will be useful to further explore conducting groups with fathers. Although some men have expressed interest in the program since its inception, there has not been consistent enough interest to get firm commitment from at least five males for any given weekly meeting time, across 3 months. As others have noted (see Pruett, Pruett, Cowan, & Cowan, Reference Pruett, Pruett, Cowan and Cowan2017), different recruitment strategies may be needed to recruit men (e.g., possibly emphasizing how they can help their younger counterparts under stress, rather than developing their own authentic connections with other fathers).

In future work, it will be essential to demonstrate that benefits of virtual groups will generalize across different facilitators, as has been done with the in-person version of the program. Following the initial randomized controlled trial using a psychiatrist (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Curlee, Tye, Engelman and Stonnington2017), in-person AC groups have been successfully conducted by women with diverse types of training including a social worker, two nursing leaders, and by an advanced graduate student in clinical psychology (all with weekly supervision). The goal now is to expand the range of facilitators running video-conference sessions as well, along with efforts to “train the trainers,” wherein those who have successfully run groups can take on supervisory roles for new facilitators, thereby bolstering dissemination and implementation (Dishion & Mauricio, Reference Dishion, Mauricio, Van Ryzin, Kumpfer, Fosco and Greenberg2015). Of course, in such expansion efforts, there will be the nontrivial challenge of ensuring fidelity to the program procedures and delivery, as is true in any efforts to take an initially promising intervention to large scale (Kazdin, Reference Kazdin2018; Weisz, Ng, & Bearman, Reference Weisz, Ng and Bearman2014).

Another limitation of the present work is that there were no randomized comparison groups, and on this front, the value of adding control participants will have to be weighed carefully if the goal is implementation on a large scale. Traditional randomized controlled trials are resource intensive, requiring between 3 and 5 years to complete from recruitment to publication of findings, and expenses are high, chiefly because of staff costs (Kazdin, Reference Kazdin2018). As a group of leading prevention scientists, including Tom Dishion, have noted (Leadbeater et al., Reference Leadbeater, Dishion, Sandler, Bradshaw, Dodge, Gottfredson and Smith2018), research funding is often available for the development and evaluation of programs, but it is relatively scant for public health or preventive interventions (and funds are even more scarce to support work with youth and parents seen as “privileged”; Geisz & Takashian, Reference Geisz and Nakasian2018). Moreover, Leadbeater et al. (Reference Leadbeater, Dishion, Sandler, Bradshaw, Dodge, Gottfredson and Smith2018, p. 458) argued, “If positive effects have already been clearly demonstrated with the targeted population, a research design involving a no-treatment control group would appear unnecessary and potentially unethical.”

A related limitation is that our findings on mechanisms were limited to qualitative responses to open-ended questions. In future work, it could be useful to obtain quantitative data on measures of mediation mechanisms posited in this paper. It might also be useful to obtain quantitative scores on diverse adjustment indices before and after the intervention, with an additional follow-up, as was done in the original AC Groups trial (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Curlee, Tye, Engelman and Stonnington2017). However, as noted before, this level of data gathering calls for additional time from participants and considerable time from research staff. Thus, the costs and benefits of pursuing multiple waves of quantitative data must be weighed against pragmatic considerations of resources involved, as is true, once again, for all efforts to scale-up intervention programs with initial evidence of promise (Kazdin, Reference Kazdin2018; Weisz et al., Reference Weisz, Ng and Bearman2014).

Offsetting the concerns noted are some notable strengths of this study, beginning with documentation of the program's external validity. In essence, effectiveness of the ACV Groups program has now been replicated across six sets of groups in different real-world settings. Thus, there is little fear of the “implementation cliff” wherein positive results are decreased when moving from the laboratory to the community (Weisz et al., Reference Weisz, Ng and Bearman2014), as the program was designed to be delivered in women's everyday life spaces. There is also evidence of “face validity” on the need for and appeal of such groups, as seen not only in data presented here but also in the development of several news stories, conjointly suggesting that the groups did strike a chord among contemporary mothers (Arizona PBS, 2018; Arizona Public Media, 2018; PBS Cronkite News, 2018; PBS NewsHour, 2019; Telis, Reference Telis2018).

Implications for future work: Practice, theory, and research

The high responsiveness to the AC Groups program, summarized above, implies that there are large unmet needs for authentic connections among today's well-educated mothers, and other bodies of evidence also point to this same conclusion. To begin with, Americans in general are experiencing a loneliness epidemic with one of two people lacking meaningful relationships that make them feel known and understood (Pollack, Reference Pollack2018). Strains on this front can be pronounced for higher socioeconomic status mothers. Over the last few decades, well-educated women have shown much greater increases in time spent on tasks related to their children as compared to their male counterparts, and as compared to mothers with less education (Kalil, Ryan, & Coey, Reference Kalil, Ryan and Corey2012; Ramey & Ramey, Reference Ramey and Ramey2010). Thus, these women are particularly stretched thin, with little time to devote to strong personal friendships. In addition, for mothers in the workforce, their multiple obligations at work and home—including “the second shift” with children (Hochshild & Machung, Reference Hochschild and Machung1989) and invisible labor in the household (Ciciolla & Luthar, Reference Ciciolla and Luthar2019)—can greatly exacerbate risks for burnout professionally, and depletion personally.

Greater vulnerability to depression and anxiety may also be implicated among well-educated mothers. In Zigler's classic writings on social competence, high developmental levels are linked to greater capacities for introspection, and people's capacities to reflect on their own thoughts and feelings, in turn, can perpetuate guilt and depression (Zigler & Glick, Reference Zigler and Glick2001). Research has shown that mothers with high ego development did show greater deterioration in the presence of personal distress than did their low developmental level counterparts (Luthar, Doyle, Suchman & Mayes, Reference Luthar, Doyle, Suchman and Mayes2001). In other research, high levels of verbal intelligence have been found to be linked to relatively high levels of worry and severity of rumination (Penney, Miedema, & Mazmanian, Reference Penney, Miedema and Mazmanian2015).

Further exacerbating vulnerability is the contagion of distress, as these mothers are typically “first responders” to their children, who are generally in highly competitive schools and are at elevated risk for serious adjustment difficulties (Luthar, Kumar, & Zillmer, Reference Luthar, Kumar and Zillmerin press; NASEM, 2019). In a recent policy report on adolescent wellness, the top four environmental risks highlighted, in order, were exposure to poverty, to trauma, to racism and discrimination, and to excessive pressures to achieve (usually seen in relatively well-educated communities; Geisz & Takashian, Reference Geisz and Nakasian2018). Corroborating evidence is seen in findings on large, national samples, showing U-shaped links between community affluence and levels of youth maladjustment (Coley, Sims, Dearing, & Spielvogel, Reference Coley, Sims, Dearing and Spielvogel2018; Lund, Dearing, & Zachrisson, Reference Lund, Dearing and Zachrisson2017).

Finally, also relevant are recent panel data showing increases in serious depression over the last decade in high-income groups, and among females in particular. Twenge, Cooper, Joiner, Duffy, and Binau (Reference Twenge, Cooper, Joiner, Duffy and Binau2019) examined changes over time for four cohorts/generations, and considering four groups of family incomes. Among adolescents, time period increases in rates of major depressive episode were the largest in the highest quartile of income, as among adults, cohort increases in suicidal ideation were the largest (in both cases, increases were the smallest in the lowest income groups). In addition, among adults, the increases in mood disorder indicators and suicidal thoughts, plans, and attempts were all consistently higher among women than among men (this would, naturally, include mothers). Conjointly, all these factors imply that women such as those in the present study do experience heightened challenges to psychological well-being.

In closing, it is perhaps useful to acknowledge that some might see the highlighting of well-educated mothers’ stresses as unseemly or even inappropriate, given the high unmet needs of families in poverty. In reality, however, there is no reason to neglect either group, as this is not a zero-sum game, and moreover, what is called for differs considerably by families’ contexts (NASEM, 2019). For mothers in low-income communities, preventive interventions will require investment of finances to support clinicians who can mobilize groups in community settings (as in RPMG and the MOMS partnership). In the case of more affluent mothers, financial resources are not required. Instead, what is needed is the promotion of greater awareness, among the mothers, about the multiple threats to their well-being; the costs of over-commitment to the “I can, therefore I must” mindset; the need for and benefits of mutual support; and perhaps, the provision of some structure or guidance to help initiate support groups within their own communities.

Conclusions

Tom Dishion's great wish was to bring supportive preventive interventions to children and families in their own communities, maximizing feasibility of offerings in terms of both resources required and ease of access. Resonant is the approach that is emphasized by pioneers in child clinical psychology (Kazdin, Reference Kazdin2018; Weisz et al., Reference Weisz, Kuppens, Ng, Vaughn-Coaxum, Ugueto, Eckshtain and Corteselli2019), by the current generation of resilience researchers (e.g., the Luthar & Eisenberg, Reference Luthar and Eisenberg2017, collection), and in major social policy reports (NASEM, 2019). There is converging emphasis that the most critical need of the day (going beyond advocating for still more research) is to harness what we already know from decades of science, in offering interventions that can feasibly be offered on a large scale. Prevention researchers must work to maximize the well-being of all children known to be “at risk,” and this is most effectively done via an upstream strategy, proactively ensuring that those who take care of them are strong and healthy. Findings presented here suggest the value of pursuing implementation of support groups such as those described here to reach caregivers in need, systematically and on a larger scale, in the years ahead.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Authentic Connections. We extend our sincere thanks to the women who took time from their schedules to participate in these virtual groups and the caring that they brought to them.