No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

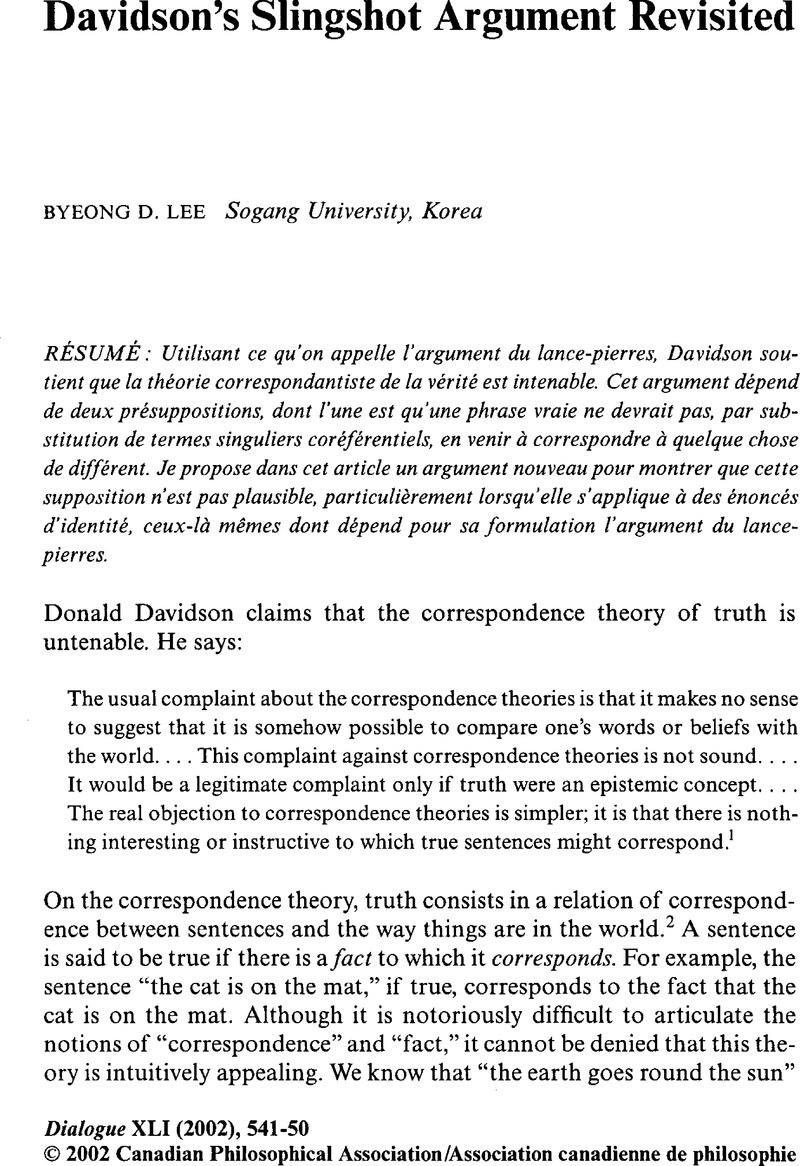

Davidson's Slingshot Argument Revisited

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 April 2010

Abstract

- Type

- Articles

- Information

- Dialogue: Canadian Philosophical Review / Revue canadienne de philosophie , Volume 41 , Issue 3 , Summer 2002 , pp. 541 - 550

- Copyright

- Copyright © Canadian Philosophical Association 2002

References

Notes

1 Davidson, Donald, “The Structure and Content of Truth,” Journal of Philosophy, 87 (1990): 302–303.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

2 I shall ignore the distinctions among sentences, statements, and propositions in this article and talk only about sentences.

3 Davidson, Donald, “Truth and Meaning,” in his Inquiries into Truth and Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), p. 19. This was originally published in Synthese, 17 (1967): 304–23.Google Scholar

4 Frege, Gottlob, “On Sense and Reference,” in Translations from the Philosophical Writings of Gottlob Frege, edited by Geach, Peter and Black, Max (London: Basil Blackwell, 1970), pp. 56–78.Google Scholar

5 Church, Alonzo, “Carnap's Introduction to Semantics,” Philosophical Review, 52 (1943): 298–305.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

6 Barwise, Jon and Perry, John, “Semantic Innocence and Uncompromising Situations,” Midwest Studies in Philosophy, Vol. 6: The Foundations of Analytic Philosophy (1981): 387–403, esp. p. 395.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

7 Davidson “The Structure and Content of Truth,” p. 303.

8 Ibid., p. 305.

9 Ramsey, F. P., “Facts and Propositions,” in his The Foundations of Mathematics (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1931), p. 146.Google Scholar

10 Note that this criterion is weaker than the so-called “existentialist criterion of fact-identity,” according to which facts are identical if and only if they necessarily co-exist. The modal criterion of fact-identity is the left-to-right direction of this biconditional. Unlike this direction, it is controversial whether the right-to-left direction also holds. According to the structural criterion of fact-identity, facts are identical if and only if they have the same constituents combined in the same way. On this criterion, the right-to-left direction does not hold. For the fact that Fa necessarily co-exists with the fact that Fa & 3 + 4 = 7 but, unlike the former, the latter contains the number 3 as a constituent. Fortunately, the modal criterion, which is very plausible, suffices for the purpose of this article.

11 Rodriguez-Pereyra, Gonzalo, “Searle's Correspondence Theory of Truth and the Slingshot,” Philosophical Quarterly, 48 (1998): 513–22.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

12 Ibid., p. 517.

13 This principle is essentially the same as an assumption that appears in Gödel's Slingshot, according to which “Fa” and “a = (ix)(x = a & Fx)” stand for the same fact. Gödel's Slingshot is vulnerable to essentially the same criticism I raise against Davidson's Slingshot in this article. For a discussion on Gödel's Slingshot, see Neale, Stephen, “The Philosophical Significance of Gödel's Slingshot,” Mind, 104 (1995): 761–825.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

14 Oppy, Graham, “The Philosophical Insignificance of Gödel's Slingshot,” Mind, 106 (1997): 121–41, esp. p. 125.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

15 Armstrong, D. M., A World of State of Affairs (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997), p. 2.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

16 Ibid., p. 87.

17 Rodriguez-Pereyra, “Searle's Correspondence Theory,” p. 517.

18 Rodriguez-Pereyra also points out in his article (ibid., pp. 517–18) that if the facts corresponding to (2') and (3') were identical they would also be identical to the fact that Socrates is identical to Socrates, and yet “the fact that Socrates is Socrates surely differs from the facts that Socrates is moral and that Socrates is an Athenian.” In this respect my argument is similar to Rodriguez-Pereyra's. But his point of all this is that “'our intuitions' about fact-identity are a mess” (ibid., p. 520) and, hence, we cannot invoke intuitions to dismiss the Slingshot argument. But the lesson here, I think, is rather that principle (II) is simply implausible with regard to identity sentences.

19 Ibid., p. 518.

20 Ibid., p. 519.

21 Ibid., p. 518.