A ‘NEW’ CONCERTO BY HAYDN

On 24 March 1784 an advertisement in the London press announced a concert that evening, one in a series organized by Lord Abingdon. As customary with this series, ‘the Hanover-Square Grand Concert’, the advertisement featured programme details. While performances of Haydn ‘overtures’ (symphonies) were usual by this date, this concert featured a Haydn composition in a genre new to England: ‘A new Concerto Violoncello, Mr Cervetto, composed by Haydn.’Footnote 1 This concerto was repeated at the following week's concert, allowing the same audience (this being a subscription series) a second opportunity to appreciate a work previously unheard.Footnote 2

During the course of two seasons organized by Abingdon, 1783 and 1784, the cellist who performed this concerto, James Cervetto, played three further concertos, while his instrumental colleague in 1783, Jean-Louis Duport, performed four concertos in one season. As usual at this date, no advertisement specifies the name of any of the composers of these works. Solo concertos were rarely identified in newspapers by composer, the only names worthy of mention being the soloists, occasionally with the implication that a soloist had also composed the work.Footnote 3 The specific claim that the concerto performed in March 1784 was ‘composed by Haydn’, Abingdon's ‘first composer in the world’,Footnote 4 therefore signalled something exceptional. Widely reported to have been in correspondence with Haydn, and with a public profile to safeguard, Abingdon could hardly promise a composition ‘by Haydn’ in a series designated the ‘First Concert in the World’ were it not what it purported to be.Footnote 5

The advertisement of 24 March emphasizes that the concerto was ‘new’, a word implying both first performance and recent composition. Furthermore, ‘new’ here probably conveyed the sense that it was written especially for Abingdon's series, as advertisements for other compositions in the series appear to show unequivocally.Footnote 6

JAMES CERVETTO

The soloist in both London performances of Haydn's concerto, James Cervetto (1748–1837), was one of England's leading instrumentalists during the 1780s.Footnote 7 Taught by the noted cellist Jacob Cervetto (died 1783), James quickly eclipsed his father in ability.Footnote 8 According to Burney, while the elder Cervetto had ‘infinitely more . . . knowledge of the finger-board’ than most cellists of his generation, his ‘tone . . . was raw, crude, and uninteresting’.Footnote 9 By contrast,

[James] when a child had a better tone, and played in a manner much more chantant than his father. And, arrived at manhood, [James's] tone and expression were equal to those of the best tenor voices.Footnote 10

Burney later recounted that ‘in riper years, [Cervetto] was as much noticed at the opera for his manner of accompanying recitative, as the vocal performers . . . were for singing the airs’.Footnote 11 Even the Prince of Wales, taught cello by Cervetto's friendly rival John Crosdill (1751–1825), recognized James's superior beauty of tone:

Although his Royal Highness was so partial to Crossdill [sic], it did not prevent his . . . appreciating the merits of Cervetto, his talented competitor. Speaking of the performances of these eminent men, [the Prince] was heard to say that the execution of Crossdill had all the fire and brilliancy of the sun, whilst that of Cervetto had all the sweetness and mildness of the moonbeam.Footnote 12

When a rumour circulated that Crosdill might replace Cervetto as principal cellist at the Italian opera, commentators were dismayed:

The professional ability of both these masters is undisputed: all we would say is, that for the accompaniment of the recitative, no violoncello could be more perfectly excellent than Cervetto's. We wish Crosdill may be as good.Footnote 13

The rumour proved false, but the very thought of it left critics reeling: ‘If Cervetto had been displaced to have made Room for Crosdill, we should have considered that as a Change to be . . . regretted’.Footnote 14

What opera audiences in the 1780s appreciated about Cervetto's style of accompaniment is signalled in an account charting changes in performance practice of Handel recitatives:

[When] some delay intervened in the rhythmical proceeding of the music, [Cervetto] played arpeggios and other florid figures on his violoncello, which were much admired by lovers of the instrument and enthusiasts for the artist. Cervetto went to the Ancient Concerts full of the praise he had received for his operatic exhibitions, and inserted such arpeggiated arrangements into the recitatives until he was stopped[.] . . . no such thing as the prominence of the violoncello could be allowed in the recitative as the playing of double stops on the cello, or running up divided notes on the chord, which were entirely out of character [for earlier music].Footnote 15

As another admirer expressed it, Cervetto was adept at ‘taking and sprinkling chords . . . as an accompaniment in recitative, an art [now] almost lost’.Footnote 16 Despite criticism of his manner of accompanying recitatives at the Ancient Concert, audiences were delighted by the beauty of Cervetto's tone in vocal music.Footnote 17 At a concert in the 1790 season of the Ancient Concert, for example, he played the cello obbligato in the aria ‘Gentle Airs’ from Handel's Athalia. Although one critic berated the singer's ‘raw, unfinished, and inexpressive’ recital, the aria succeeded because

[It] gave Cervetto an opportunity of enrapturing his hearers with a captivating performance on the Violoncello: – the cadenza, which was finely fancied, displayed the great master [Handel], and the execution was in the first style, – it was perfection!Footnote 18

CERVETTO'S TECHNIQUE

A caricature dated 1789 drawn by John Nixon provides a visual token of Cervetto as accompanist (Figure 1), together with the celebrated castrato Luigi Marchesi. Both men (identified through inscriptions) appear on a platform matching descriptions of the Hanover Square concert room, suggesting the scene was drawn from life. In 1789 Cervetto and Marchesi contributed to all twelve fixtures comprising the Professional Concert series at Hanover Square, at the close of which Nixon published his caricature as ‘A Bravura at the Hanover Square Concert’.Footnote 19 Since all Marchesi's identifiable music required orchestral accompaniment, it seems likely that Nixon's decision to depict Cervetto as the only instrumentalist was an indication of the latter's popularity with audiences. As the season's star attraction, Marchesi is the focus. Cervetto's complementary status implies a favourite London performer, his distinctive profile rendering him easily recognizable.

Figure 1 John Nixon, A Bravura at the Hanover Square Concert (1789). Original inscriptions identify the singer as Luigi Marchesi and the cellist as James Cervetto. Pen and ink and brown wash, 23.5 x 16.8 cm. London, National Portrait Gallery, NPG 5179. Used by permission

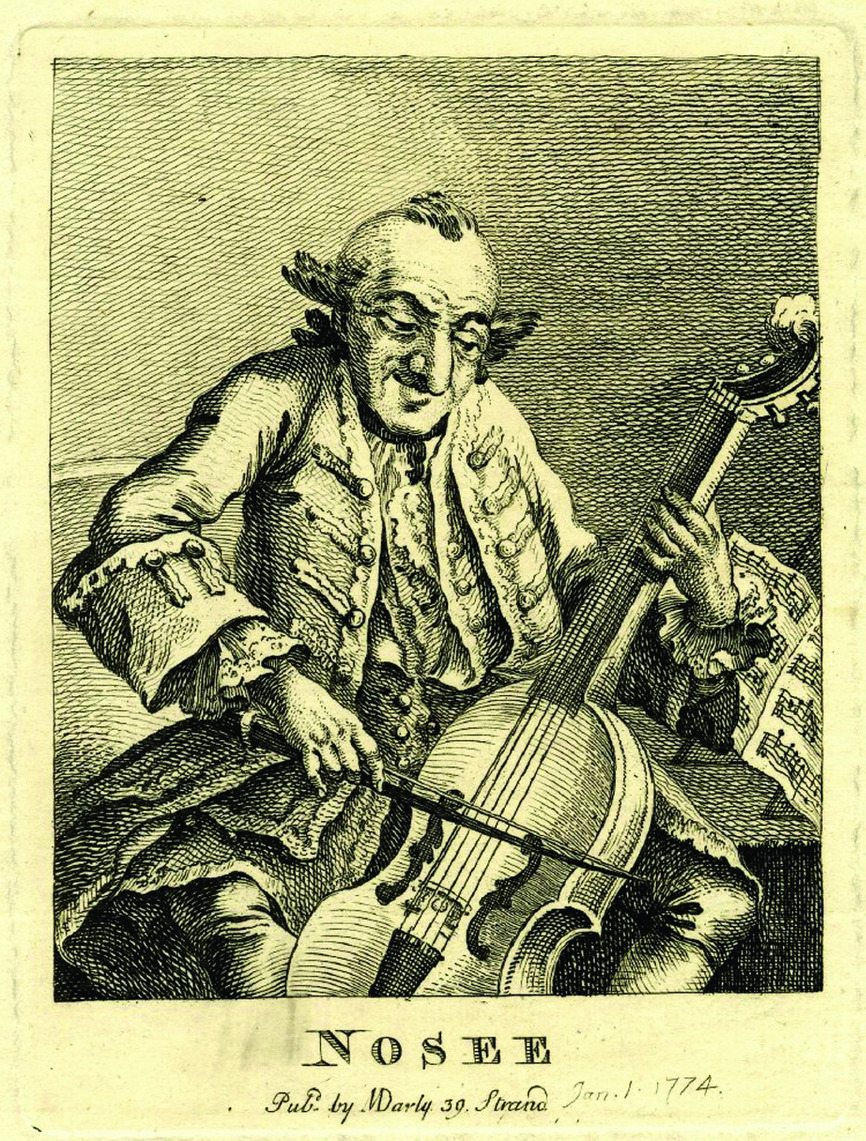

Here Cervetto had something in common with his father, a popular performer with a significant following.Footnote 20 A caricature captioned ‘Nosee’, Jacob's nickname, depicts the elder Cervetto playing the cello (Figure 2).Footnote 21 Based loosely on a print reproducing a portrait of Jacob by Johan Zoffany (1733–1810) (Figure 3), the image arguably mocks the ‘raw, crude’ aspects of the elder Cervetto's playing noted by Burney.Footnote 22 By contrast, caricatures of the younger Cervetto convey more polish and ease in his performance.

Figure 2 Nosee (M. Darly, 1 January 1774). A satirical portrait of Jacob Cervetto. Etching, 5.5 x 11.7 cm. London, British Museum, BM J,2.70. Used by permission

Figure 3 Mme Victor Marie Picot, after Johan Zoffany, Jacob Cervetto (Picot & Delattre, 16 April 1771). Zoffany provides an insight into Jacob Cervetto's celebrated fingerwork on the fingerboard. Mezzotint, 35.2 x 24.7 cm. London, British Museum, BM 1912,0416.216. Used by permission

‘A Sunday Concert’ (1782) depicts James in the company of several celebrity musicians (Figure 4).Footnote 23 Private concerts were a feature of later eighteenth-century London musical life, where professional musicians supplemented incomes and, like their hosts, consolidated reputations.Footnote 24 ‘A Sunday Concert’ satirizes this form of social affectation, already a dubious convention when (as seems likely here) music inappropriate to the Sabbath was performed, by ridiculing its participants through their performance. In Cervetto's case the fingers of his left hand are shown extremely high on the fingerboard. While Zoffany's portrait of Jacob (Figure 3) shows the conventional means of performing in the cello's higher register, his thumb locked behind the fingerboard, his son's performance as here depicted, with the thumb placed across the strings higher up, evidences a greater mastery of their instrument, here depicted as an element of the pretentiousness of the occasion.

Figure 4 A Sunday Concert (M. Rack, 4 June 1782). The cellist is James Cervetto. It seems clear that the caricaturist depicts him performing in thumb position. Etching, hand-coloured, 35.0 x 49.0 cm (image). Courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University, 782.06.04.04

In the caricature James reads the harpsichordist's part as he accompanies the castrato Pacchierotti. Cervetto therefore notionally follows the bass line, which would not normally require the use of any higher registers. There is, however, no doubt that James had a reputation for performing in the upper register of his instrument so comfortably that he could easily play the parts of higher stringed instruments should the occasion require, at sight if necessary. In chamber music, for example, he readily took the viola part on the cello, leaving Crosdill the designated cello part.Footnote 25 John Marsh records an occasion in 1778 when Cervetto

was so obliging as to take either fiddle, tenor [viola], or bass upon the violoncello as happen[e]d to be wanted; particularly an obligato fiddle accomp[imen]t to a harpsich[or]d lesson of Boccherini's . . . w[hi]ch he played inimitably well.Footnote 26

This was a formidable test of technique. The ‘lesson’ in question is identifiable as one of Boccherini's Op. 5 sonatas (g25–30), first published in London c1770.Footnote 27 Even for a competent violinist the set makes considerable demands, with many spread chords involving double and triple stopping, and a range on the violin extending to e4. In 1783 an edition of this set was published in London, ‘with alterations, which render their execution more easy; from perceiving the great, and almost insuperable difficulties . . . scholars formerly experienced, in attempting to play them, as originally composed’.Footnote 28 The editor was chiefly concerned with the keyboard part; but his phrase ‘almost insuperable difficulties’ applies equally to the violin, made yet more demanding by performance on the cello. For Cervetto to play this part at pitch (which the context implies) and create an acceptable sound – he ‘played inimitably’ – was a formidable feat of virtuosity.

A portrait by the painter Zoffany, executed little more than a year before James performed Haydn's concerto, also depicts the player's fingerboard technique (Figure 5).Footnote 29 Noted both for truthfulness of detail and for his musical understanding, Zoffany has a special claim to have captured accurately the technicalities of musical performance.Footnote 30 Zoffany's picture is an elaborate group portrait, with James at its centre drawing his bow across the strings of his instrument. James's enthusiastic gaze, looking out of the picture and radiating self-confidence, is a means of engaging the attention of viewers, creating an audience for his impromptu performance. The image, though silent, implies the music James plays and his effortlessness in creating it. To the right of the composition is Jacob – depicted in profile, though clearly the same sitter Zoffany portrayed in the late 1760s (Figure 3). In the later portrait, Jacob's pose shows him looking directly at his son's performance. Jacob's right hand is held to the side of his head, less for support than to indicate how intently he listens to James's playing, implying something exceptional.

Figure 5 Johan Zoffany, Self-portrait with his daughter Maria Theresa, James Cervetto, and Jacob Cervetto (c1782–1783). Zoffany's composition is arranged so that Jacob Cervetto looks intently at his son's left hand, showing the use of thumb position with an extended fourth finger depressed on a string. Oil on canvas, 193 x 164.5 cm. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, New Haven, Connecticut

On the left stands the painter, his features familiar from other self-portraits. Zoffany portrays himself in front of a canvas, entirely blank except for the shadow of his palette and brushes, which falls such that it appears behind the upper part of the fingerboard of James's cello, a pictorial contrivance that encourages a parallel to be drawn between James's dexterity in playing his instrument and the painter's in setting about his work. The parallel is encouraged by the way the composition is organized so that the motif of James holding his right arm around his instrument in order to play is also echoed by Zoffany's depiction of himself with his right arm supporting a young girl, identifiable as his own daughter Maria Theresa. She stands on the footrest on which James is seated, permitting her a view of his performance. In his right hand Zoffany holds a brush, which both points to James and parallels how James holds his bow.

The composition implies that Jacob is sitting for his portrait, with Zoffany poised to begin. James has accompanied his father to the sitting, but chooses this moment to perform. Jacob's chair, drawn close to Zoffany's canvas, indicates his readiness for the sitting. But instead of facing the painter, Jacob places one arm along the back of his chair, enabling him to turn sideways towards James. Jacob's concentrated expression and the arrested pose of Zoffany and his daughter show them momentarily captivated by James's performance, their enchantment conveyed through rapt attention and James's beaming face. Zoffany's composition temporarily suspends the act of painting, giving precedence to music, a tribute to James's artistry.

Recalling, as Zoffany surely did, that Jacob was a cellist formerly noted for dexterity in the upper fingerboard implies the significance of the pose. As Zoffany shows, James is so mesmerizing that even Jacob is absorbed by his performance. Zoffany's depiction of James's finger positions is exceptionally precise. Comparison with representations of noted cellists of the period in performance – like Boccherini, Cirri and Hebden – by other artists suggests, once more, that Zoffany's powers of observation are unprecedented.

Instead of depicting the thumb behind the neck of the instrument with the fingers stretched along the fingerboard to reach higher notes, as in Figure 3, Zoffany shows James's thumb being pressed against the upper strings in the middle of the fingerboard, in the position where theoretically the harmonic occurs.Footnote 31 Since the 1780s this technique has been known as ‘thumb position’.Footnote 32 It entails a shift of the whole hand to the lower half of the fingerboard, locked in place by the thumb in order to find notes that cannot be attained in conventional positions along the instrument's neck. Zoffany also shows all James's fingers, including the fourth, engaged with the strings in a challenging passage, probably signalling three or more notes sounding (near-)simultaneously. This explains Jacob's astonishment. He leans forward to look closely, a motif that was probably meaningful because, as Zoffany's earlier portrait of him shows, Jacob needed spectacles for music. His concentration helps convey the vibrancy of his son's musicality.

Thumb position had first developed in the second quarter of the eighteenth century.Footnote 33 The composer Michel Corrette (1707–1795) first explained it in a treatise published about 1741. A second edition appeared in 1783, the year before the London performance of Haydn's concerto.Footnote 34 Between the dates of these editions many composers showed an understanding of the technique, including Haydn, whose writing for the solo instrument often implies use of the thumb position, including the C major concerto.Footnote 35 Cello composers documented in London at this time, like Cirri and Francesco Zappa, composed with an understanding of the technique, suggesting that Jacob Cervetto also practised it, though amateur cellists avoided its use until well into the nineteenth century.Footnote 36

What probably distinguished James's technique from that of his fellow cellists is, as Zoffany shows, that he made use of the fourth finger in thumb position, a matter of difficulty. The finger is clearly depressed to create a sound when bowed, as the painter represents. Corrette comments that the use of the fourth finger was only practical in higher positions on the neck, not in thumb position, where it was too short and, if stretched, produced only unsustainable sound.Footnote 37 Zoffany's representation, however, shows a further detail suggesting that James had strong fourth fingers that were used to overcome technical challenges. In holding the bow, Zoffany shows the fourth finger of James's right hand on the same side of the bow as his thumb, contrary to traditional recommendations.Footnote 38

In Duport's treatise for cellists of 1806, which employs a method of fingering distinct from Corrette's, thumb position is explained in relation to all scales, strings and double stops, with the use of the fourth finger occasionally advocated, showing that this usage was then gaining adherents.Footnote 39 Between the treatises of Corrette and Duport it seems clear that significant developments took place in cello technique, with James Cervetto among the pioneers. Since he and Duport were instrumental partners at Abingdon's concerts throughout the 1783 season, it seems likely some exchange took place between them concerning matters under consideration.

Although Zoffany's picture is undated and undocumented, circumstantial evidence indicates that its execution overlapped with this very concert season, raising the possibility that in part it paid tribute to an aspect of Cervetto's technical proficiency then only recently perfected. That this was to do with his left thumb is implied by Zoffany's use of this motif as a focal point of the composition, underlining its significance by emphasizing his own left thumb holding the palette, immediately above James's head, a motif used only in this picture. The painter certainly completed the picture before leaving for an extended stay in India in March 1783, though not necessarily before Jacob's death in January. Since Zoffany's daughter Maria Theresa, born in April 1777, looks at least five years old in the picture, sittings were probably held late in 1782.

A plausible reason why Zoffany left England in 1783 was a lack of prestigious commissions.Footnote 40 The prominence of the painter and his daughter in the picture suggests that it is unlikely to have been a commissioned work, but was perhaps executed speculatively, drawing on long-standing acquaintance between the families and on James's celebrity at the time. The picture not only contrasts painting with music, it also presents parallels between two fathers and their respective offspring, commenting on the transfer of creative powers between generations. Zoffany, who cultivated friendships with many musicians, here celebrates the flourishing of James's career and technical innovation. Meanwhile Zoffany's empty canvas implies his own career has drawn a blank.

HAYDN'S CELLO CONCERTO IN D MAJOR

Haydn's catalogue of his own compositions, assembled in about 1805, features three concertos for cello.Footnote 41 Since the incipit for the third concerto (hVIIb:3) essentially repeats that for the first, contradicting Haydn's customary avoidance of compositional repetition, it is accepted today that this entry was an inadvertent mistake, leaving Haydn with two authentic concertos for cello.Footnote 42

The first of these, in C major (hVIIb:1), is known from a set of early parts rediscovered in 1961.Footnote 43 Scholars agree on the basis of its listing in a catalogue Haydn started to keep soon afterwards, the Entwurf-Katalog, that this composition dates to the period c1761–1765. It seems unlikely therefore that the ‘new’ cello concerto ‘by Haydn’ performed in 1784 was the one in C major, then approximately two decades old. Although the evidence of surviving parts suggests that this concerto was played at venues beyond Haydn's immediate control early in its history, the same parts point to transmission only within regions closely connected with Haydn's homeland, as was usually the case with the composer's music in the 1760s.

The concerto performed in London in 1784 may therefore reasonably be equated with Haydn's second concerto, in D major (hVIIb:2), today known from two sources dating from the composer's lifetime: first, Haydn's autograph, which he inscribed ‘[1]783’ on its cover page, a date consistent with the designation ‘new’ attached to the concerto performed in London in March 1784; and secondly, its first publication (as Op. 101) by the Offenbach firm of André, probably in 1804.Footnote 44

Unlike the Concerto in C major, no parts for the D major concerto survive prior to its eventual publication. For an orchestral composition performed in London during this period, this is unsurprising. While manuscript parts made for publication purposes survive, no manuscript parts are extant relating to performance in London of any Haydn composition from the 1780s, despite the well-documented regularity of such events. When performances of such compositions ceased, manuscript parts were probably disposed of, possibly to protect copyright interests once agreed performances had been given.

However, the fact that no manuscript performance materials from Continental Europe survive is significant, the earliest evidence of interest in the D major concerto being its publication in about 1804.Footnote 45 Although this is no proof of total non-performance beyond London before the concerto was printed, the fact that no trace of performance exists is uncharacteristic of Haydn's compositions from the 1780s and is clearly relevant to the concerto's early history.

Before rediscovery of the concerto's autograph in the mid-twentieth century the work was associated with the cellist Anton Kraft (1749–1820), a performer in Haydn's orchestra at Eszterháza between 1778 and 1790.Footnote 46 This association was first made in print in an entry published in a volume issued in 1837, part of the Encyclopädie der gesammten musikalischen Wissenschaften, edited by Gustav Schilling. The entry makes the bold claim that the concerto, identified through the name of the 1804 publisher, was actually composed by Kraft. The Encyclopädie, an authoritative work of musical reference, states that the concerto was Kraft's earliest composition, ‘submitted to Haydn for review’:

Haydn, die Vorzüglichkeit desselben erkennend, glaubte, aus angeführtem Grunde, dem jungen Künstler sein Urtheil darüber lieber schuldig bleiben, als dasselbe gegen seine Ueberzeugung aussprechen zu müssen, und ließ daher das Manuscript unter seinen Papieren liegen, das K[raft], in der Meinung, nichts Gutes geschaffen zu haben, weil Haydn ganz darüber schwieg, aus gewissermaßen künstlerischer Schaam auch nie wieder zurückverlangte. Wir halten uns nicht ohne Grund so lange bei diesem Gegenstande auf: es ist der Vorfall wichtig, zum wenigsten bibliographisch interessant, denn eben dieses Concert Kraft's ist dasjenige Violoncellconcert, welches später, nach Haydn's Tode, als Nachlaß von ihm auch unter seinem Namen (Offenbach bei Andre) gedruckt wurde, und bis zur Stunde noch allgemein für ein wirkliches Werk Haydn's gehalten wird, während es doch, was Schreiber dieses aus bester Quelle weiß, unserm Kraft angehört. Es ist das einzige Violoncellconcert, das wir unter Haydn's Namen besitzen, und es kann daher keine Verwechselung statt finden.Footnote 47

Haydn, who recognized its excellence, decided on questionable grounds to hold back his opinion on it from the young artist, rather than having to offer a view that went against his inner conviction, and so he left the manuscript lying around amongst his papers. Kraft, in the belief that what he had written was no good, on account of Haydn's total silence, never asked for the manuscript back – out of artistic shame, so to speak. We record this information here at length for a very good reason: it is an important fact, of significant bibliographical interest, that this concerto by Kraft is the very one that later, after Haydn's death, was published posthumously under Haydn's name (by André at Offenbach) and which hitherto has been considered a genuine work of Haydn's, whereas the writer of this article understands from the best of sources that it is actually by our Kraft. This is the sole violoncello concerto that we possess with the name of Haydn, and from now on this misattribution need not be maintained.

It is not difficult to identify the perpetrator of this misinformation, ‘the best of sources’ referred to by the article's author. He is the subject of the very next entry in the Encyclopädie, an article on the cello virtuoso Nicolaus Kraft (1778–1853), Anton's son. Despite the fact that Anton had worked with Haydn in the 1780s, it is telling that the younger Kraft was unaware that Haydn had written an earlier concerto for the instrument, arguably evidence of a more circumspect relationship between Haydn and Anton than the Encyclopädie sought to convey.

In the 1830s both Nicolaus Kraft and Schilling were based in Stuttgart, so identification of Nicolaus as Schilling's source is unproblematic.Footnote 48 Nicolaus's principal motivation in this deception was evidently to exaggerate his father's reputation as well as his own. For his version of events to be credible, Nicolaus had to have assumed that Haydn's autograph was unavailable – in fact knowledge of its existence may be traced throughout the nineteenth centuryFootnote 49 – and that André’s publication postdated Haydn's death in 1809, a means of implying that the concerto only came to light in Haydn's estate after he died.Footnote 50

In fact, though André’s publication (Haydn's Op. 101) is undated, the approximate date of publication, probably early in 1804, may be deduced from its plate number and its position within the publisher's sequence.Footnote 51 In 1804 Haydn was still very much alive. In the years immediately before this, André (1775–1842) had been actively negotiating to publish original compositions by composers in Vienna. The best known of these are by Mozart, those that in 1799 remained unpublished. For these André entered into an agreement with Mozart's widow to purchase the composer's autographs.Footnote 52 Constanze's correspondence shows that André was pursuing these interests in Vienna before 1800. He probably took the trouble to see Haydn, whose compositions his firm had regularly published in unauthorized editions. Although no record of direct contract between André and Haydn survives, there is little doubt that André was actively seeking original compositions by Haydn by 1801, since the composer mentions this in correspondence. An André associate was – somewhat irritatingly, according to Haydn – trying to negotiate rights to publish The Seasons in score, a clear indication of André’s desire to acquire new Haydn compositions.Footnote 53

Although Haydn sold The Seasons to a rival firm, Breitkopf & Härtel, André persisted. His publication of Haydn's concerto features the phrase ‘d'après le Manuscrit original de l'auteur’ (from the composer's original manuscript) on the title-page. Similar phrases appear on title-pages of André’s early editions of the Mozart works that had been supplied by Constanze. In the case of Haydn's concerto, comparison between André’s publication and the autograph indicates that the assertion is correct, strongly suggesting that André either acquired the autograph, like those by Mozart, or had access to it. Whatever the case, it seems likely that publication was a result of André’s dealings with Haydn, who evidently retained the autograph, only copies having been sent to London in 1783, in line with Haydn's usual practice.

Correspondence from 1803 shows that Haydn was then systematically going through autographs of his earlier unpublished compositions with a view to selling them. In June there is mention of an organ concerto (hXVIII:1), which Haydn was still trying to sell early the following year.Footnote 54 Although an earlier work than the cello concerto, its history during the early 1800s suggests the way Haydn was then thinking. There is, however, a significant distinction between this and the 1783 concerto. When the organ concerto was written (possibly 1756), there was no prospect of publication in print. By the 1770s, however, evidence suggests Haydn had begun negotiating with publishers, a situation formalized in 1779, when his contract with his princely patron was changed to permit this, reflecting the new commercial reality. The fact that a work written in 1783 took twenty years to reach publication therefore requires an explanation.

ABINGDON'S CONCERT SERIES

The documented performances of Haydn's concerto in 1784 were in concerts organized by Abingdon, amateur flautist and dilettante composer. Abingdon's collaborations with Haydn in London in the early 1790s are well documented, arguably an outcome of a dialogue already established in the 1780s.Footnote 55 Although Abingdon considered the series that featured the concerto insufficiently remunerative to support a further season (1785), both concert series he organized (1783 and 1784) were critically successful.

From July 1782, when preparations for Abingdon's first series were underway, it was regularly reported that the Earl was in negotiation with Haydn.Footnote 56 Although Haydn never appeared in London at this time, subscribers were informed that compositions written specifically for performance in London had been received from Haydn and that these were performed at Abingdon's concerts.Footnote 57 No correspondence between Haydn and Abingdon survives from this period. However, in a letter to a Parisian publisher written in July 1783, Haydn mentions symphonies commissioned for London in 1782, which tends to confirm the London reports.Footnote 58 Abingdon was experienced in negotiating with composers, having already commissioned music for personal use from such figures as Grétry, J. C. Bach and Abel.Footnote 59

Burney preserved a note of terms that Abingdon reached with Haydn for the 1783 season:

[Haydn] was engaged to Compose for L[or]d Abingdon's Concert and was expected in England ab[ou]t the end of the year 1782; but did not come, as the security of his money: (£300, & travelling expenses from Vienna; & at the end of the season [that is, 1783] £100 more for Copy-right of the 12 Pieces he was to compose for the concert, of whatever kind he pleased, if he c[oul]d not dispose of them more to his advantage.)Footnote 60

Although Haydn certainly supplied music for Abingdon's first season of concerts, the extent to which the terms recorded by Burney were met is unclear, though the terms as set out here can hardly have been Burney's invention. An independent source, however, implies that Haydn was dissatisfied with them, leading to fresh negotiations for the 1784 season. An account of ‘Milord Abingtons Concert [sic]’ dated December 1783, published in Cramer's Magazin der Musik, records that ‘In Absicht Haydens, von dem ich Ihnen lezthin schrieb, muß ich nunmehro sagen, daß alle Hofnung, ihn hier bey uns zu sehen, verschwunden ist. Er hat uns unser Gesuch in einer cathegorischen Bitte abgeschlagen, uns aber doch versprochen, uns alles, was wir wänschten, zu componiern, wenn man ihm die Summe von 500 Pfund Sterling geben wollte’. (Hayden's intention . . . to come here [to London] has turned out to amount to nothing. He has categorically turned down our [that is, Abingdon's] offer but promised to compose anything we wish if he receives the sum of £500)’.Footnote 61 For his first season in charge it seems Abingdon left it to Haydn to decide what to send; but for the second season, when perhaps a better dialogue had been established, it appears Haydn put it to Abingdon that he would compose whatever was desirable for the requisite fee.

This evidence suggests how the commission for a cello concerto for London probably came about. Several (unidentifiable) cello concertos were performed during the 1783 season, showing how concertos for this instrument were a much-appreciated feature of Abingdon's concerts, showcasing the virtuosity of the cellists he employed. Sitting alongside Cervetto in 1783, often performing as a soloist, was Duport, whose distinction as a performer is attested not only by his later treatise, but also by Beethoven's cello sonatas Op. 5 (1796), which Ferdinand Ries says the composer wrote for Duport and first performed with him. Employing such distinguished cellists in 1783 helps explain Abingdon's commitment to commission a new work for this instrument.

As Burney's summary of terms relevant to 1783 indicates, copyright featured in negotiations. Haydn was to receive a fee for what would today be understood as performance rights for this season, at the end of which, had he not secured separate contracts for publication meeting the composer's remunerative expectations, Abingdon would purchase the copyright for the agreed amount, supplementing Haydn's fee. Since such copyright would only have been effective within British territories, Haydn was free to make separate agreements, were this possible, in other countries for the same compositions.Footnote 62

Whatever compositions the composer sent to Abingdon, Haydn sold publication rights for them (probably several times over) quite separately to his arrangement with Abingdon, with the result that the Earl neither paid for nor held copyright for any Haydn work composed for the 1783 season.

While symphonies published soon after the seasons in question probably formed the core of the music Haydn sent to Abingdon, the cello concerto, unpublished for two decades, was evidently in a different situation. Unlike the symphonies, it seems there was no commercial interest in a concerto requiring such virtuosity that few players could perform it.Footnote 63 In general, only instrumental music with the potential for performance by able amateur musicians made it into print.

Even cello music written for publication by noted virtuoso cellists, like Anton Kraft and James Cervetto, was not intended primarily as demonstrations of their own skill but to meet the expectations of talented players, working within prevailing limits of technical possibility.Footnote 64 While a general tendency towards increased difficulty in solo cello writing is evident in music published late in the eighteenth century, only Boccherini's concertos approach the level of virtuosity in Haydn's concerto. One of Boccherini's most challenging such works, published as Op. 34 and advertised in London in August 1783, was possibly among the unidentified concertos performed in Abingdon's 1783 series.Footnote 65 If so, its availability in print only served to emphasize the exclusivity of Haydn's concerto, technically accessible only to the most outstanding soloists. The concerto's difficulty therefore arguably excluded it from publication, leading Haydn to take the option of selling his rights to it to Abingdon, who had no practical use for them. Thereafter Haydn would have been prevented from selling the concerto to a British publisher for fourteen years, the period stipulated in copyright law of the time.

By the time Abingdon died (1799) the hypothetical arrangement posited here would have lapsed. Only when his creative activity ceased, forced on Haydn by deteriorating health around 1803, one might suggest, did he reconsider its commercial potential. Since 1784 several cello concertos by former Haydn associates had been published, perhaps encouraging him to reassess his own concerto.Footnote 66

THE KRAFTS AND CERVETTO

Hitherto the distinctive technical aspects of Haydn's concerto have consistently been associated with Anton Kraft. Even after Haydn's autograph resurfaced in the early 1950s, indisputably demonstrating authorship, the Kraft connection was so entrenched that commentators speculated that Haydn's supposed inexperience meant he required help writing for the cello, thereby accounting for the 1837 attribution to Kraft.Footnote 67 Musicologists explicitly suggested a parallel with the contribution made by Joseph Joachim to the solo part of Brahms's violin concerto, well documented in correspondence and in Brahms's autograph.Footnote 68

The suggestion of collaboration, however, fails to take account of Haydn's autograph. In contrast to Brahms's autograph, Haydn's provides no indication that the composer responded to advice from an instrumentalist preparing to perform it. Had Kraft been the intended soloist from the outset, he was on hand to shape the concerto as work progressed. But any alterations to Haydn's autograph are clearly minor self-corrections, not responses to technical advice.Footnote 69 As usual with Haydn autographs, his intentions suggest confidence and are easily followed, something essential to ensure accuracy of copying.Footnote 70 None the less, even after the rediscovery of the earlier cello concerto demonstrating unequivocally Haydn's competence in cello writing without any help from Kraft, then unknown to the composer, the notion that Kraft contributed to the D major concerto persisted.Footnote 71

Nicolaus Kraft, however, surely knew the truth of the concerto's origin, from his father.Footnote 72 As an advisor to Schilling, Nicolaus provided further misinformation that led astray readers of the Encyclopädie. Its article on the Cervettos, signed ‘K’, showing Kraft contributed it himself, includes the statement that, ‘after Mara, [James Cervetto] was the greatest virtuoso violoncellist in the whole of England’ (‘James C., der seiner Zeit, nächst Mara, für den größten Violoncell-Virtuosen in ganz England galt’).Footnote 73 Although this seemingly flatters Cervetto, it really demeans him. Johann Baptist Mara (1746–1808), though deemed ‘a good player’, was as likely to be called a ‘bad’ one.Footnote 74 He was barely noted for any distinctive musicality during the periods he was in Britain (1784–1788 and 1792–1799). At concerts in Westminster Abbey commemorating Handel in 1784, Mara was specifically mentioned as occupying the ‘second’ desk of cellos, while Cervetto and Crosdill occupied the first desk, evidence flatly contradicting the Encyclopädie.Footnote 75 Mara was better known for exploiting the success of his wife, one of the greatest singers of the age, and, as ‘an idle drunken man’, for general bad behaviour.Footnote 76 Mozart, writing in 1780, provides an account of Mara's contemptible conduct towards other distinguished musicians, describing him as ‘a wretched violoncellist, as everyone here [in Munich] says’ (‘ein elender Violoncellist wie alles hier sagt’).Footnote 77 Haydn, observing Mara in London in the 1790s, records similar antics.Footnote 78 Implying that James ranked below Mara might be construed as humiliating.

‘1741’, the year of James's birth supplied by the Encyclopädie, prematurely ages him by seven years. Since James's actual birth is clearly documented, this misinformation looks like a calculated attempt to undermine his status as a prodigy. His first public appearance was in 1760, when James was claimed to be ‘eleven Years old’ (he was actually twelve) in a concert of ‘young Performers’ that included the future Madam Mara.Footnote 79

The Encyclopädie proceeds to mention a well-known Continental tour that concluded in 1770, a fortune inherited from his father and an account of James's participation in the concert series of ‘Lord Abingdon’, beginning in 1780. This mistake – Abingdon's first series was in 1783 – might be explained as inadvertent. However, unintentionality certainly cannot explain the Encyclopädie’s most glaring inaccuracy concerning Cervetto. After stating erroneously that the latter part of his career was unsuccessfully devoted to composition – James's first opus, a set of accompanied cello sonatas, was successfully published when he was nineteenFootnote 80 – the Encyclopädie gives the year of James's death as 1804.Footnote 81 Cervetto was actually still living when this very report of his demise was published (1835). In 1836 Cervetto's attendance at a London rehearsal was reported, noting that he had then been ‘a member of the Royal Society of Musicians for seventy-one years!’.Footnote 82 Cervetto's death in 1837 prompted several obituaries.Footnote 83 But when a revised edition of the relevant volume of Schilling's Encyclopädie appeared in 1840, the mistake was left uncorrected, despite the event having been widely published elsewhere.Footnote 84

The thirty-three years that James lived after 1804 was a period spent largely in retirement. Among the last recorded occasions when he performed for an audience was at a private concert given in London in 1795 by Haydn, attended by members of the royal family.Footnote 85 Not unsurprisingly, Cervetto was on affable terms with the composer. Although Cervetto does not appear on Haydn's list of pre-eminent cellists drawn up in London in 1791, his retirement from professional engagements provides an explanation.Footnote 86 Having lost his favourite cello in a fire in 1789, he honoured his contract for the 1790 season; thereafter he only performed privately.Footnote 87 One occasion was a performance before George IV: ‘the last musical treat the king enjoyed . . . was the performance of Corelli's sonatas by that mighty master of the violoncello, the admired and unrivalled Cervetto, with Schram, and Dragonetti’.Footnote 88 Performing trios intended for two violins and bass (from Corelli's Opp. 1–4) was clearly a special feat of virtuosity, demonstrating Cervetto's command of his instrument into the 1830s.

A LONDON CONCERTO

The Encyclopädie’s false information about Cervetto, undermining his standing, was clearly contrived to support Nicolaus Kraft's fabricated account of Haydn's D major cello concerto. Contemporary reviews of the 1784 concerts at which Cervetto performed the concerto, however, stress how Haydn's score was ideally matched to Cervetto's expressive powers, opening up the possibility that Haydn specifically conceived the concerto with knowledge of Cervetto's known strengths: ‘Cervetto's violoncello concerto brought with it (as we expected) the grace, the solemn strength, and the sublimity of music’.Footnote 89

Grace, dignity, solemnity, strength and sublimity are hardly qualities applicable to any cello concerto of this period. They help to capture the singular eloquence of Haydn's concerto as realized by its first performer. In 1784, these qualities had strong associations with Handel, whose famous Commemoration began the following month. In particular, ‘sublimity’ was in London connected near-exclusively with this composer's revered choruses in the elevated style. Alluding to sublimity in connection with Haydn's concerto marks the beginning of a willingness to sense this mode in Haydn's music, which thereafter intensified.Footnote 90

‘Grace’ represents a separate strand in British aesthetics, an aspect of the Beautiful, the main category contrasted with the Sublime. Identifying both grace and sublimity within a single work suggests an innovative way of conceiving musical composition befitting both Haydn's concerto and Cervetto's skill in performing it.

Haydn's D major cello concerto is exceptional in other ways. Noticeably less condensed than most eighteenth-century concertos, all three movements unusually combine a sense of intense expressivity with a relaxed, expansive lyricism. A premium is placed on gentle reflective beauty of sound (‘grace’) and leisurely unfolding of melodic material rather than any striving after dramatic effects or concision of form, qualities generally recognized as representative of Haydn's instrumental compositions of the 1780s. Cervetto's playing was particularly admired for the very traits played up in the D major concerto – the strengths on which his reputation was built – emphasizing delight and expression over tension and rapidity of execution. Although the available evidence does not permit a conclusive case, it seems plausible to suggest that Haydn was here responding to Cervetto's special forte, his power to conjure up ‘all the sweetness and mildness of the moonbeam’.

Despite its leisurely character, the concerto is one of the most demanding to be found in the entire eighteenth century, posing distinct technical difficulties. In addition to double stopping, Haydn featured specialized effects not found in his earlier concerto, perhaps specified when commissioned in 1783. One is the instruction to employ natural harmonics at the top end of the cello range, in bar 175 of the first movement. Notated conventionally with small circles above the relevant notes, Haydn marked these passages ‘flautino’ in the autograph (Figure 6), indicating a special resonant flute-like sound, unique within Haydn's output but arguably responding to Cervetto's reputation for ‘sweetness and mildness’. Another special timbre is indicated by Haydn's instruction to use low strings in some high passages, a special test of a soloist's skill, one that Cervetto would have relished: ‘sul G’ and ‘sul D’ in the first movement at bars 50 and 153 respectively.

Figure 6 Haydn's autograph of the D major cello concerto, fol. 18r (first movement, bars 173–177). Haydn's marking ‘Flautino’ may be seen in the third bar beneath two notes marked to be played as harmonics. Articulation marks in the solo part in the subsequent two bars are later additions to the score. These appear in André’s edition of c1804. Courtesy of Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

Despite its lack of dramatic pacing, no cello concerto of the period has a greater claim to brilliance, remarkably well suited to a soloist with a reputation for ‘arpeggios and other florid figures’ and ‘running up divided notes’. All three movements provide generous opportunities for the solo part to sing, placing a premium on this above any of the display of technical prowess characteristic of many contemporary concertos. Furthermore, the concerto's solo part calls for extensive use of thumb position, especially in the last movement.Footnote 91 In one passage there, a top note (at the end of bar 54) is ideally performed using the soloist's fourth finger, an exceptional technical demand in the 1780s, though one that Zoffany's portrait of Cervetto implies he accomplished shortly before the concerto was commissioned.Footnote 92 Indeed, James's temperament as a performer, his ability to hide a phenomenal technique such that difficult music sounded relaxed, matches well the unparalleled sound world of Haydn's concerto.

One aspect of this is the concerto's use of melodic content suggestive of folk idioms. Although Haydn often drew on themes derived from Eastern European traditions, commentators have noted that the main theme in the concerto's last movement has a contour reminiscent of a traditional air known only in the British Isles, later sung to the words ‘Here we go gathering nuts in May’.Footnote 93 Haydn's tune is not precisely the same, but, as scholars have pointed out, there are clear resemblances in character and motive, hitherto interpreted as evidence either of Haydn's lack of inspiration, or of Anton Kraft's intervention.Footnote 94 A more likely explanation lies in the idea that Haydn received thematic suggestions from London to help him shape a concerto for an English audience. The ‘nuts in May’ theme appears in various guises in published sources from eighteenth-century Britain, including one in a successful ballad opera first performed in London in 1762.Footnote 95 Cervetto and Abingdon certainly knew the theme in this form. They were also familiar with the use of traditional tunes in composing for public concerts.Footnote 96

The idea that Haydn refashioned melodic material furnished by Abingdon is not far-fetched; this was precisely what happened at a later date. A movement from a trio for two flutes and bass that Haydn composed in about 1795 (hIV:2) uses the tune of a song by Abingdon as the theme of a set of variations.Footnote 97 Similarly, a set of ‘Twelve Sentimental Catches and Glees’ was ‘Melodized’ by Abingdon with ‘Accompaniments’ by Haydn.Footnote 98

Haydn thought Abingdon a poor composer.Footnote 99 He probably used Abingdon's melodic material in the interests of cordiality, important when business transactions were involved. Other composers found themselves in similar positions. Grétry recalled composing a concerto that he says made use of themes by Abingdon, implying that the Earl expected composers he commissioned to make use of melodic material that he himself had furnished.Footnote 100 Grétry's situation – his concerto dates from the late 1760s – therefore presents a precedent for what probably happened to Haydn in 1783. What have sometimes been viewed as old-fashioned features for a concerto composed in 1783 may perhaps also be best understood in the same light, as Haydn's interpretation of Abingdon's commission.

CONCLUSIONS

Recognition that Haydn's D major cello concerto was a London commission, and a vehicle for Cervetto's distinctive mode of performance, satisfactorily explains those aberrant qualities that have often been detected in it.

Instead of viewing it as ‘an uncomfortable composition for the 1780s, displaying . . . misjudgments of dramatic timing’,Footnote 101 it may be suggested that the concerto was deliberately composed like this to suit the temperament of its original soloist. What have been considered negative traits – the first movement ‘proceeds laboriously’; the second lacks ‘a feeling of spontaneity’; and the third ‘sounds staid and melodically short-winded’Footnote 102 – may instead be seen as intentional objectives (rather than failings) of the composer, interpreting specific demands that came with the commission. Supposed ‘weaknesses’ hitherto explained by postulating intervention from Anton Kraft may alternatively be understood as Haydn's responding to Abingdon's requirements.

Acknowledging that the concerto was intended for London also enables us confidently to contradict the frequent assertion that the cello concerto was alone among Haydn's instrumental music of the 1780s in not owing its origins to an external commission.Footnote 103 Finally, appreciating its London origin allows the concerto to take its place as a forerunner of Haydn's later London compositions, and indicates that Haydn's connections with London around 1783 were more substantial than hitherto acknowledged.