TRAZOM'S WIT IN THE 1770s

Vienna, 21 August 1773: Mozart signs off a letter to his sister Nannerl in his usual jocular manner: ‘oidda – gnagflow Trazom neiw ned 12 tsugua 3771’. The signature is of course a backward spelling of ‘Addio. Wolfgang Mozart. Wien, den 21. August 1773’.Footnote 1 Later, in 1777, while relating the details of a performance and improvisation for the canons of the Heiligkreuz Monastery in Augsburg, Mozart refers to a similar retrograde inversion in a musical context as the ‘arseways’ (arschling) repetition of a theme, one set immediately after a passage of a ‘humorous character’ (das scherzhafte Wesen).Footnote 2 These ‘arseways’ inversions of linguistic and musical symbols are early examples of many similar jests scattered throughout the Mozart correspondence, illustrating the composer's well-known fondness for playing with patterns – spatial, arithmetical, linguistic and musical.Footnote 3 Mozart appears to have been especially committed to such games in the 1770s. A year before the Trazom letter, again writing to his sister, now from Milan (18 December 1772), every other line of Mozart's message was penned upside down.Footnote 4 And in that same year, he also busied himself with musical puzzles, composing solutions to the riddle canons featured in the first two volumes of Giovanni Battista Martini's Storia della musica (1770).Footnote 5 But the 1770s were also a period of more serious professional activity for the young Mozart, and for the Mozart family in general, a time when Wolfgang was actively seeking to ‘attract a publisher and cultivate a patron’ – initially Archbishop Colloredo's sister, Princess Maria Theresia.Footnote 6 In the first half of the decade, Mozart composed the set of six keyboard sonatas k279–284, which became important parts of his portfolio.Footnote 7 The Köchel-Verzeichnis describes these works as Mozart's ‘bleibende Repertoirestücke’ (enduring repertoire pieces),Footnote 8 owing to reports of their frequent performance. Both father and son refer to them as ‘difficult sonatas’.Footnote 9 And Wolfgang repeatedly mentions his performing the entire set on every possible occasion during his city tours. For instance, from Augsburg, on 17 October 1777, he writes to Leopold: ‘Here and at Munich I have played all my six sonatas by heart several times’;Footnote 10 and a month later, on 4 November 1777, now from Mannheim, he reports on having again ‘played all my six sonatas today at Cannabich's’.Footnote 11 Importantly, this is not the case for the earlier set of four (also solo) keyboard sonatas, kApp 199–202/33d–g, now lost, and known only from a manuscript catalogue written for or by the publisher Johann Gottlieb Immanuel Breitkopf in Leipzig.Footnote 12 Not only does Wolfgang never mention performing this earlier set (along with the later set), but in efforts to persuade Breitkopf to print the ‘difficult’ collection (the earlier and presumably easier set being already in Breitkopf's possession), Leopold also described the sonatas as being in a ‘very popular’ style, ‘the same style as those of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach “mit veränderten Reprisen” [with varied reprises]’ (letter dated 6 October 1775).Footnote 13 Though k279–284 were never published as a set during Mozart's lifetime,Footnote 14 their characterization as both ‘difficult’ and ‘popular’ in the Mozart correspondence suggests a certain amount of ambition as well as a desire for a broad remit. Against the backdrop of the family's collective attempts to advance Mozart's career (with Nannerl sharing time at the keyboard),Footnote 15 these details surrounding their composition suggest that the set was composed with the intent of impressing or attracting the attention of potential future patrons, publishers or employers.

But Mozart's liking for various games and jests in the 1770s was by no means independent from his concurrent musical-professional activities. Three days before writing to Leopold to report on his performances of the k279–284 set, Wolfgang describes a meeting with the fortepiano builder Johann Andreas Stein, for whom Mozart played, and whose instruments would become Wolfgang's prized possessions (letter dated 14 October 1777). Upon arriving at Stein's, Mozart first presented himself in disguise: ‘“Is it possible that I have the honour of seeing Herr Mozart before me?” “Oh no”, I replied, “my name is Trazom and I have a letter for you.”’Footnote 16 Mozart's chronicle of their meeting is a wonderful illustration that his humour was not confined to the private world of communication with family, but also extended into the public sphere and professional activity, surfacing not only in interactions with colleagues, but also finding unique musical expression. Musical symbols could be ‘arseways’ no less than linguistic ones: it was on Sunday of that same week (19 October 1777) that Mozart would jest with the monks at Heiligkreuz, where he also played one of the six ‘difficult’ sonatas. And not long after writing the earlier letter to Nannerl in 1773, signed Gnagflow Trazom, we find Mozart's application of this humour to the domain perhaps most relevant to music: that of syntax and grammar. Once again addressing Nannerl, from Munich on 30 December 1774, Mozart writes: ‘My greetings to all my good friends. I hope, you will – farewell! – I see to hope you soon in Munich’ (‘Ich hoffe, Du wirst – lebe wohl! – Ich sehe Dich bald in München zu hoffen’).Footnote 17 The intended message was seemingly ‘I hope to see you soon in Munich’ (‘Ich hoffe Dich bald in München zu sehen’). The ellipses and parenthetical insertions result in a number of grammatical infelicities, and a witty grammatical inversion of the lexical items ‘hope’ and ‘see’: ‘I see to hope’ (Ich sehe zu hoffen) is an inversion – an ‘arseways’ reworking – of ‘I hope to see’ (Ich hoffe zu sehen).Footnote 18

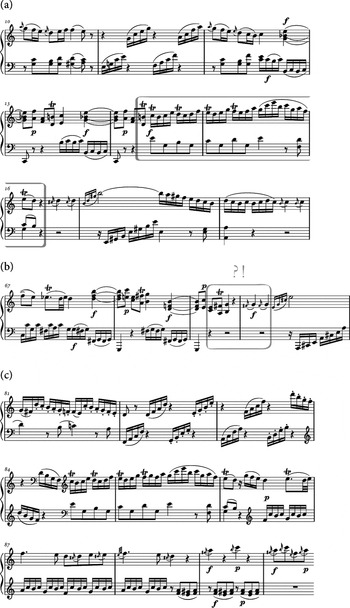

A similar kind of mischief appears to underlie another peculiar statement by the eighteen-year-old Mozart, from the first surviving keyboard sonata, k279 in C major, composed around the time of this letter, possibly in the same year (1774).Footnote 19 The opening Allegro of the sonata contains a rather bizarre gesture that centres on a thematic module profiled in Example 1a.Footnote 20 This passage is set in relief against the other thematic material of the movement, as it carries the busiest rhythmic texture of the entire Allegro, produced by the ascending semiquavers adorned with trills in the top voice. The module first appears in the codetta appended to the principal theme, which dissolves into something of a transition that closes with a medial-caesura half cadence at bar 16 (Example 1a). At the analogous point of the recapitulation (Example 1b), this material is conspicuously absent, and the corresponding medial caesura (bar 69) is now oddly articulated as a result, particularly in the minor sixth (B–G) that is left hanging in the upper register without the support of a bass, which creates a sense of incompleteness, as if conveying an unfinished thought. Rather than close with a semicolon, the equivalent phrase is truncated by an ellipsis. More curiously, Mozart later explicitly restates this module, retrospectively highlighting its omission from the earlier passage by reinserting it in a most unexpected location: within the recapitulation's second theme (Example 1c).

Example 1 Mozart, Keyboard Sonata in C major, k279/i, Allegro (1775): (a) bars 10–18, (b) bars 67–70, (c) bars 81–90 (Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 9, volume 25/1, Klaviersonaten Band 1, ed. Wolfgang Plath and Wolfgang Rehm (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1986)). Used by permission

Try as one might, the unexpected re-entry of the module in the second group and its blatant omission earlier in the recapitulation resist easy causal explanation – certainly as structurally integral and inevitable features of the work. Nor does any broader aesthetic rationalization suggest itself. The opening Allegro, in John Irving's words, projects a vague ‘curiosity about ideas in play’, leaving open the question as to whether ‘Mozart ha[d] an[y] express intention’ with k279.Footnote 21 Present-day critics might be inclined to interpret such odd behaviour as an unhappy characteristic of ‘early Mozart’ – symptoms of a youthful Mozart who, as one colleague once put it, ‘hadn't yet got it quite right’. The sonata's modern reception has indeed been less than favourable. Daniel Heartz has deemed it the ‘least interesting’ of the set,Footnote 22 and William Kinderman has identified a greater problem of surface disintegration: ‘the first movement might seem to be comprised mainly of formulas strung together in an additive, improvisatory series, not welded into the distinctive artistic synthesis characteristic of Mozart's mature music’.Footnote 23 Ultimately, Kinderman attempts to rescue the sonata from such an evaluation, by unearthing integrating properties that lie concealed beneath its overtly formulaic patterning. The impression of disintegration, he argues, ‘is to some extent deceptive’: its ‘improvisatory character … proves to be shaped by a compelling inner logic’, ‘a high degree of motivic integration’.Footnote 24 But any motivic coherence notwithstanding, the formal relocation of the module and the movement's improvisatory disposition in general remain inexplicable by intraopus analysis, motivic or otherwise. Nor does this curious relocation observe general stylistic norms regarding the omission of exposition material in the first half of a recapitulation. Normally, omitted modules would reappear in a coda, if at all, exemplifying what William Caplin has referred to as a coda's ‘compensatory function’.Footnote 25 James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy cite a later, distantly related example from the Overture to The Marriage of Figaro, whose coda specifically ‘restor[es] a TR-idea missing from the recapitulation’. As they go on to illustrate, though, ‘within the style such a restoration [in the coda] was by no means obligatory or even expected’.Footnote 26 Much less expected, then, for a transition idea to be ‘restored’ by the second theme.

COMMUNICATION IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY MUSIC

In light of the wider biographical circumstances that framed the composition of Mozart's ‘difficult’ yet ‘popular’ sonatas, this odd bit of behaviour in the Allegro of k279 and the improvisatory character of the whole appear to be deliberate and motivated. Both seem to be part of the strategy to attract the attention of possible patrons, perhaps a musical equivalent of ‘Ich sehe zu hoffen’. And yet, whatever strategy may have been implemented appears to have been lost on modern sensibilities, its effects nullified over the intervening centuries. There may be a dissonance between the contexts of the sonata's production and its unfavourable modern reception. A conversation begun in the Black Forest town of Bad Sulzburg in July of 2005 would suggest a compelling if provocative hypothesis for this disconnect: a miscommunication between Mozart's ‘message’ in k279 and present-day audiences. The Bad Sulzburg workshop on ‘Communicative Strategies in Music of the Late Eighteenth Century’, which resulted in the Cambridge collection of essays Communication in Eighteenth-Century Music (2008),Footnote 27 was founded on the central theme that musical meaning exists in a ‘context’, in a communicative code or channel, and one that is embodied by a historical listener.Footnote 28 This reflects a basic tenet of the communication sciences in generalFootnote 29 – that receivers are equal agents in the construction of meaning. Such a tenet is perhaps most explicitly and emphatically voiced in reader-response strains of communication theory: as the literary theorist Wolfgang Iser phrased it, ‘the message is transmitted in two ways, in that the reader “receives” it by composing it’.Footnote 30 Among the numerous implications of this central tenet is that ‘messages’ are easily misunderstood when ‘received’ outside the context of their production. Leonard Meyer described this as the communicative distortion or ‘cultural noise’ that inexorably accrues both with extensive ‘anthropological’ as well as ‘historical distance’.Footnote 31 Indeed, miscommunication is the keynote which sets the stage for the Cambridge volume on the whole, with the opening essay by the communication theorist Paul Cobley. Cobley outlines ‘three catalysts’ for the discussion in the form of present-day misreadings of eighteenth-century novels, including Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe (1719), Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726) and Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy (1759–1767): ‘the eighteenth century is a rich source of examples of this kind: that is, texts whose readings have radically changed from their first appearance’.Footnote 32

The source of these misreadings is a problem of ‘context’, but understood not simply as a background for communication: ‘context is not outside the communication, guiding it somehow for its participants, but, instead, actually is the communication’.Footnote

33

‘Context’ refers to a symbolic system used in a particular time and place. The problem of musical ‘context’ is therefore a problem of eighteenth-century norms, styles and genres, as musical equivalents of what cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz called the ‘shared symbols’ of a culture.Footnote

34

The communicative study of eighteenth-century music is consequently oriented to an analysis of these tacit symbols and their customary use. Meyer, who crossed paths with Geertz at the University of Chicago, was among the first musicologists who explicitly viewed music as a communicative act, and he characterized the ‘disciplinary outlook’ of his own Style and Music from 1989 as being ‘akin to that of cultural anthropology or social psychology’ in its objectification of ‘context’: ‘It is the goal of music theorists and style analysts to explain what the composer, performer, and listener know in this tacit way.’Footnote

35

Because symbol systems are tacit, they need to be made concrete, and, in the case of a historical symbol system, recovered and reconstructed – a theme common enough in several studies of late eighteenth-century music with an implicit or explicit communicative focus. The need for recuperation has been aligned with several parameters of musical organization. For example, Karol Berger has argued for the resuscitation of a lost ‘punctuation form’ at the large-scale level, as discussed by Joseph Riepel, Heinrich Christoph Koch and others;Footnote

36

Robert Gjerdingen for an excavation of buried and suppressed ‘galant’ scale-degree patterns at the phrase level to which ‘we [have] become deaf’;Footnote

37

James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy for a ‘culturally aware reading’ of sonata-form norms;Footnote

38

Giorgio Sanguinetti for the revival of ‘a complete theory of harmony and voice leading’ contained in partimenti, which ‘face[d] extinction when the context that assured its transmission disappeared’;Footnote

39

and my own communicative study of Beethoven's Eroica Symphony, Op. 55 (1803–1804), has attributed misreadings of its opening theme in the nineteenth century and beyond to the loss of a specific harmonic schema, which I have styled the Le–Sol–Fi–Sol. This features a distinctive chromatic turn of phrase in the bass oriented around the dominant: ♭![]() –

–![]() –♯

–♯![]() –

–![]() . The existence of this schema caused Friedrich Rochlitz, the editor of the Leipzig Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, momentarily to hear the Eroica as a G minor symphony that begins in medias res, as described in a review of the work from 1807.Footnote

40

. The existence of this schema caused Friedrich Rochlitz, the editor of the Leipzig Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, momentarily to hear the Eroica as a G minor symphony that begins in medias res, as described in a review of the work from 1807.Footnote

40

Thus there is in fact a private element to public communication – that is, private to the denizens of a historically contingent musical culture as insiders, which the German term for contemporaries, Zeitgenossen, captures quite pointedly: ‘time-comrades’.Footnote 41 Reconstructing a historical communicative context is therefore no easy affair, and not simply because of the tacit nature of symbol systems, or, as the communication theorist Edward T. Hall put it, because culture in general can be the most ‘silent [of] language[s]’.Footnote 42 Musical conventions also operate on several syntactic and semantic levels at once. The various grammars of phrase-level harmonic and contrapuntal schemata, formal types and so forth interact with the complex social meanings of musical topics and figures, all interwoven in a largely tacit communicative system. As part of this system messages are also embedded within messages. Eighteenth-century musical norms were designed for and interacted in different ways with different audiences. As Mark Evan Bonds's chapter in the Cambridge volume illustrates so thoughtfully, composers tailored their works to both Kenner and Liebhaber demographics. Both listener types occupied the eighteenth-century ‘compositional matrix’.Footnote 43 And, finally, the context is further complicated by the compositional play to which norms were repeatedly subjected as a corollary of their very conventionality, and often for the purpose of higher, metaphorical forms of communication such as ‘wit’, ‘humour’ and the ‘sublime’. Howard Irving related it most fittingly when speaking of Haydn's Sternian practice: ‘wit and humour can be easily misunderstood because they tend to be hermetic by design: that is, they are calculated to be intelligible only to those possessing a specific body of knowledge or even a particular intellectual outlook’.Footnote 44 The ‘semiotic historian’ who seeks to recuperate this context is therefore much like William of Baskerville, the Franciscan monk of Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose: forever caught in a veritable ‘labyrinth of signs’.Footnote 45 What requires recuperation are not simply norms and genres as things in themselves, but also their customary usage, their interactions on numerous syntactic and semantic axes, how these norms are addressed to various audiences and subjected to compositional play, and how deviations from norms become a source of metaphoric forms of communication such as wit and humour.

My ambition in what follows is to navigate the corners of this labyrinth which relate to Mozart's play with grammar in k279. I contend that the modular dislocation is part of a complex utterance in which various culturally constructed meanings afforded by the syntax of phrase-level patterning and of large-scale form, together with the semiosis of musical topics, intersect to elicit laughter or prompt a smile. This communicative strategy is yet another example of the jocular games Mozart played in the 1770s, but one that also reflects a larger aesthetics of humour and compositional play that was discussed in the writings of Johann Georg Sulzer, Heinrich Christoph Koch and others. My intention is not only to interpret the idiosyncratic details of k279 as an expression of Trazom's wit, but also to use them as an occasion to revisit the implications of the Bad Sulzburg workshop – to hold up a mirror to the communicative attributes of eighteenth-century music.

SYNTAX: PHRASE-LEVEL SCHEMATA AND ‘PUNCTUATION FORM’ (‘INTERPUNCTISCHE FORM’)

That a broad remit was intended for k279 is evident in the palpable inscription of a Liebhaber audience into its compositional matrix: an explicit storehouse of galant phraseology. The movement is composed of a limited number of phrase-level patterns, outlined in Table 1, which represent nearly the entire core repertoire of schemata discussed in Robert Gjerdingen's Music in the Galant Style. Each of these schemata is presented with a rather uncommon transparency – not just through the clarity of the movement's phrasing and overall simplicity of its figuration, but even more through the explicit assigning of a topically distinct thematic identity to each schema throughout the movement.Footnote 46 As already seen, the module from bars 14 to 16 is treated as a discrete ‘chunk’ when omitted in the recapitulation's principal theme-transition and dislocated to its second group. Looking more broadly, this ‘chunking’ process is consistent throughout the movement, which is visibly composed as a series of two- to four-bar thematic modules. The principal theme, for example, is subdivided into four bars of a vamping, brilliant style, followed by four bars of a singing style over an Alberti bass; this itself is then contrasted with a ‘preluding’ arpeggiation topic leading to the more singing-style cadences of bars 10 (deceptive) and 12 (perfect).

Table 1 The ‘vernacular dialect’ of k279/i, Allegro: galant scale-degree schemata

The use of an explicit and limited galant phrasicon was seemingly a calculated strategy for adhering to the ‘popular style’ of which Leopold spoke, and for ensuring accessibility to, and familiarity for, a Liebhaber audience. But closer inspection of the phrase level shows this square presentation of galant idioms to be a context for a deeper syntactic ‘game’ that was seemingly tailor-made for Kenner audiences: the explicit phrasicon allows for both blatant and more subtle tinkering with the syntactic properties of the aberrant module of bars 14–16. This module is a hybrid schema – a possibility that Gjerdingen briefly mentions in passing while working through Joseph Riepel's discussion of the Ponte – which contains features of both Fenaroli and Ponte: hence, the ‘Fenaroli-style Ponte’Footnote

47

(hereafter Fenaroli-Ponte). The hybrid is an explicit dominant version of the standard Fenaroli, which carries a latent potential to become a dominant pedal and is frequently used in this way. Typically, the Fenaroli consists of alternating dominant and tonic harmony, guided by a paradigmatic ![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() scale-degree progression, usually in the bass, and a canonic

scale-degree progression, usually in the bass, and a canonic ![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() countermelody, which often is realized as a quasi-canonic

countermelody, which often is realized as a quasi-canonic ![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() ; that is, the normal

; that is, the normal ![]() –

–![]() exchange between outer voices becomes

exchange between outer voices becomes ![]() –

–![]() answered by

answered by ![]() –

–![]() .Footnote

48

The schema also characteristically features a dominant pedal in the soprano or in a ‘filler’ voice. The end result is a four-stage structure, normally repeated. A quasi-canonic version is shown in Example 2a, from Haydn's Cello Concerto in C major, hVIIb:1, where it appears following a half close punctuated by a Le–Sol–Fi–Sol. Example 2b displays a canonic version from the Andante of k279. The four-stage design renders the Fenaroli both circular and open-ended, so that to clarify its underlying harmonic context, it is dependent on (hyper)metrical placement, as seen in these two examples: the Haydn expands tonic, which is positioned on beats one and three, while the Mozart expands dominant (through to bar 13), which falls on the first and third bars of a four-bar unit.

.Footnote

48

The schema also characteristically features a dominant pedal in the soprano or in a ‘filler’ voice. The end result is a four-stage structure, normally repeated. A quasi-canonic version is shown in Example 2a, from Haydn's Cello Concerto in C major, hVIIb:1, where it appears following a half close punctuated by a Le–Sol–Fi–Sol. Example 2b displays a canonic version from the Andante of k279. The four-stage design renders the Fenaroli both circular and open-ended, so that to clarify its underlying harmonic context, it is dependent on (hyper)metrical placement, as seen in these two examples: the Haydn expands tonic, which is positioned on beats one and three, while the Mozart expands dominant (through to bar 13), which falls on the first and third bars of a four-bar unit.

Example 2a Fenaroli, preceded by a Le–Sol–Fi–Sol: Haydn, Cello Concerto in C major, hVIIb:1/i, Moderato (c1761–1765), bars 76–79 (Joseph Haydn Werke, series 3, volume 2, Konzerte für Violoncello und Orchester, ed. Sonja Gerlach (Munich: Henle, 1981)). Used by permission

Example 2b Fenaroli: k279/ii, Andante, bars 10–14 (Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 9, volume 25/1, Klaviersonaten Band 1, ed. Wolfgang Plath and Wolfgang Rehm (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1986)). Used by permission

In the Ponte hybrid, the dominant pedal normally contained in a ‘filler’ or upper voice of the standard Fenaroli is positioned in the bass, while the paradigmatic ![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() line and its countermelody are relocated to upper voices, typically the soprano and tenor, resulting in a soprano–tenor exchange. Emanuel Bach's Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen of 1753–1762 provides several harmonized continuo examples of this hybrid in a larger discussion of appoggiaturas (Figure 1).Footnote

49

Bach's first example (top staff), for instance, shows a purely canonic version. With the dominant pedal relocated to the bass, the schema aligns with the Ponte family, which Gjerdingen defines as a ‘dominant pedal point’. (Caplin calls this feature a ‘standing on the dominant’, and Hepokoski and Darcy a ‘dominant-lock’.)Footnote

50

The Ponte hybrid maintains the canonic–cyclical aspects of the Fenaroli, but grounds the tonic–dominant oscillation in an overall dominant-expansion setting. At times the Fenaroli line may be paired with a second, also ascending progression,

line and its countermelody are relocated to upper voices, typically the soprano and tenor, resulting in a soprano–tenor exchange. Emanuel Bach's Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen of 1753–1762 provides several harmonized continuo examples of this hybrid in a larger discussion of appoggiaturas (Figure 1).Footnote

49

Bach's first example (top staff), for instance, shows a purely canonic version. With the dominant pedal relocated to the bass, the schema aligns with the Ponte family, which Gjerdingen defines as a ‘dominant pedal point’. (Caplin calls this feature a ‘standing on the dominant’, and Hepokoski and Darcy a ‘dominant-lock’.)Footnote

50

The Ponte hybrid maintains the canonic–cyclical aspects of the Fenaroli, but grounds the tonic–dominant oscillation in an overall dominant-expansion setting. At times the Fenaroli line may be paired with a second, also ascending progression, ![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() , which follows along in parallel thirds or sixths, as seen in the second of Bach's harmonized basses (Figure 1, middle staff). In this way, the ‘Fenaroli-Ponte’ is one family among several types of conventionalized formations of a dominant pedal point that were familiar to the eighteenth century, one that pairs a

, which follows along in parallel thirds or sixths, as seen in the second of Bach's harmonized basses (Figure 1, middle staff). In this way, the ‘Fenaroli-Ponte’ is one family among several types of conventionalized formations of a dominant pedal point that were familiar to the eighteenth century, one that pairs a ![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() ‘descant’ with a quasi-canonic, purely canonic and/or sequential countermelody over a dominant bass pedal.

‘descant’ with a quasi-canonic, purely canonic and/or sequential countermelody over a dominant bass pedal.

Figure 1 Fenaroli-Ponte, canonic, sequential, and six–four types: Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Versuch über die wahre Art das Klavier zu spielen, volume 2 (Berlin, 1762), chapter 25, unnumbered example, 215–216

As Gjerdingen himself described it, the Fenaroli's ‘overall “feel” is often of sequential ascents, frequently in canonic imitation’.Footnote

51

Johann Schobert's Sonata for Harpsichord and Violin Op. 2 No. 1, published in Paris between about 1761 and 1767, juxtaposes both the canonic and cyclical types (at different levels of augmentation and diminution) to construct a lengthy dominant pedal following a half cadence (Example 3). The two upper-voice settings were also frequently combined into a more intricate polyphony, particularly by Germanic composers, resulting in a complex embroidery that interlaces the quasi-canonic exchanges with sequential parallel thirds, as seen in Schobert's later Harpsichord Quartet Op. 7 No. 1 (Example 4). In these braided cases, the Fenaroli line that begins on the leading note is often given a broader ambitus that outlines a pentachord or hexachord extending to scale degree 4 or 5 (![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() [–

[–![]() ]); see bars 21–26 of Example 4. And in solo keyboard writing, where all this galant polyphonic manoeuvring can be impeded by the physiognomy of the instrument, especially the production of longer rhythmic durations, the bass pedal – sustained by the cello in Schobert's quartet – is characteristically drawn out by an animated Trommelbass texture. Example 5 displays a rhythmically more elaborated instance from a keyboard sonata by the Neapolitan composer Domenico Cimarosa, which carries a syncopated dominant scale degree in the bass, a distinctive feature of the schema, with the Fenaroli lines also characteristically fitted as a soprano–tenor exchange. The polyphonic Trommelbass accompaniment, an otherwise very common texture widespread in the second half of the century,Footnote

52

was a standard way of exposing the soprano's counterpointed line in the tenor – which in multi-instrument works is brought out by timbral differences, as in the Schobert quartet – while sustaining the dominant pedal through continuous reiteration and syncopated emphasis. This attribute of the pattern is most evident in the no fewer than six iterations of the schema that Mozart employs in the ‘Lützow’ Fortepiano Concerto, k246, also in C major and roughly contemporary to k279 (composed in 1776). Example 6 aligns the Fenaroli ‘descant’ with the several different harmonizations supplied by the horns and fortepiano over the course of the movement. The fortepiano's Trommelbass accompaniment in quavers with syncopated dominants (bottom staff) is a variant of the Trommelbass in semiquavers with dominants accented on the downbeat (next-to-bottom staff), and of the sustained dominant bass pedal in the horns (middle staff).

]); see bars 21–26 of Example 4. And in solo keyboard writing, where all this galant polyphonic manoeuvring can be impeded by the physiognomy of the instrument, especially the production of longer rhythmic durations, the bass pedal – sustained by the cello in Schobert's quartet – is characteristically drawn out by an animated Trommelbass texture. Example 5 displays a rhythmically more elaborated instance from a keyboard sonata by the Neapolitan composer Domenico Cimarosa, which carries a syncopated dominant scale degree in the bass, a distinctive feature of the schema, with the Fenaroli lines also characteristically fitted as a soprano–tenor exchange. The polyphonic Trommelbass accompaniment, an otherwise very common texture widespread in the second half of the century,Footnote

52

was a standard way of exposing the soprano's counterpointed line in the tenor – which in multi-instrument works is brought out by timbral differences, as in the Schobert quartet – while sustaining the dominant pedal through continuous reiteration and syncopated emphasis. This attribute of the pattern is most evident in the no fewer than six iterations of the schema that Mozart employs in the ‘Lützow’ Fortepiano Concerto, k246, also in C major and roughly contemporary to k279 (composed in 1776). Example 6 aligns the Fenaroli ‘descant’ with the several different harmonizations supplied by the horns and fortepiano over the course of the movement. The fortepiano's Trommelbass accompaniment in quavers with syncopated dominants (bottom staff) is a variant of the Trommelbass in semiquavers with dominants accented on the downbeat (next-to-bottom staff), and of the sustained dominant bass pedal in the horns (middle staff).

Example 3 Fenaroli-Ponte, canonic and sequential types: Johann Schobert, Keyboard Sonata with Violin Accompaniment in B flat major, Op. 2 No. 1/ii, Andante (1761–1767), bars 47–64 (London: Longman and Broderip[, 1761–1767 or later])

Example 4 Fenaroli-Ponte, combined canonic and sequential types: Johann Schobert, Harpsichord Quartet in E flat major, Op. 7 No. 1/i, Allegro moderato (1764), bars 16–33 (London: R. Bremner[, 1764 or later])

Example 5 Fenaroli-Ponte, Trommelbass type: Domenico Cimarosa, Keyboard Sonata in E flat major, c74 (c1770s), bars 50–52 (Domenico Cimarosa: Sonate per clavicembalo o fortepiano, volume 2, ed. Andrea Coen (Milan: Zanibon, 1992)). Used by permission

Example 6 Fenaroli-Ponte, ![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() descant aligned with several different accompaniments: Mozart, Fortepiano Concerto in C major, ‘Lützow’, k246/i, Allegro aperto (1776) (Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 5, volume 15/2, Konzerte Band 2, ed. Christoph Wolff (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1976). Used by permission

descant aligned with several different accompaniments: Mozart, Fortepiano Concerto in C major, ‘Lützow’, k246/i, Allegro aperto (1776) (Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 5, volume 15/2, Konzerte Band 2, ed. Christoph Wolff (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1976). Used by permission

Irrespective of the upper voices' particular setting (sequential or canonic, or their braided interlacing), the Ponte variant of the Fenaroli obviates the metrical dependency of the standard version by clarifying a dominant expansion via the pedal in the bass, even when tonic harmony is positioned on (hyper)metrically strong beats. This six–four variant is also among Bach's harmonized basses (bottom staff of Figure 1), and is featured among the several Fenaroli-Pontes of Mozart's slightly later ‘Jeunehomme’ Concerto, k271, from 1777 (Example 7a). Though the metric distribution of tonic and dominant chords here and in the Haydn cello concerto example are identical, with tonics placed on strong beats (compare Examples 7a and 2a), the scale-degree-five pedal in the ‘Jeunehomme’ Concerto clarifies an overall dominant orientation following a half cadence. An earlier example is found in one of Haydn's Esterházy Sonatas, hXVI:21 in C major (1773), which derives from the Op. 13 collection published one year before Mozart's own C major Sonata (k279), and said to have been an influence on the first five of Mozart's set (Example 7b).Footnote 53 Caplin has discussed bars 10–12 as a ‘prolong[ation]’ of a tonic ‘six-four chord … by neighboring dominant sevenths’, which initiates a ‘dominant arrival’ in advance and anticipation of a proper half close.Footnote 54 The Fenaroli-Ponte brings out this ‘prolong[ation]’, whose paradigmatic lines are once more realized as a soprano–tenor exchange. In this six–four variant of the schema, tonic six–four chords serve to expand dominant harmony and function.Footnote 55

Example 7a Fenaroli-Ponte, six–four type: Mozart, Fortepiano Concerto in E flat major, ‘Jeunehomme’, k271/ii, Andantino (1777), bars 43–47 (Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 5, volume 15/2, Konzerte Band 2, ed. Christoph Wolf (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1976). Used by permission

Example 7b Fenaroli-Ponte, six–four type: Haydn, Keyboard Sonata in C major, hXVI:21/ii, Adagio (1773), bars 9–12 (Joseph Haydn Werke, series 18, volume 2, Klaviersonaten, ed. Georg Feder (Munich: Henle, 1970)). Used by permission

The eighteen-year-old Mozart would certainly have known many of these examples well – Schobert's music he admired, studied closely, imitated and literally incorporated in his own compositions,Footnote

56

and Haydn's sonatas are a noted influence. And in terms of its structure, Mozart's setting of the Fenaroli-Ponte in k279 (

Example 8) is exemplary – a cross between the various models he would have encountered in the 1760s and early 1770s, particularly those of Schobert. It features the more complex embroidery of combined canonic and sequential upper voices, the larger hexachordal ambitus to the Fenaroli ‘descant’ (![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() ) and the animated Trommelbass appropriate for keyboard writing. Mozart's usage, however, deviates from customary practice, and does so with the schema's very first appearance – that is, even before its omission and unexpected reinsertion in the second group. To begin with, the Fenaroli-Ponte in k279 is preceded by a Quiescenza schema; see bars 12–14. Gjerdingen's statistics (Figure 2) for schema collocation – the habitual juxtaposition of one schema with another – show that neither the Fenaroli nor the Ponte, as an individual pattern, is ever preceded by the Quiescenza.Footnote

57

As the table shows, they both issue frequently from the ‘Converging Cadence’, a specific type of half close with a

) and the animated Trommelbass appropriate for keyboard writing. Mozart's usage, however, deviates from customary practice, and does so with the schema's very first appearance – that is, even before its omission and unexpected reinsertion in the second group. To begin with, the Fenaroli-Ponte in k279 is preceded by a Quiescenza schema; see bars 12–14. Gjerdingen's statistics (Figure 2) for schema collocation – the habitual juxtaposition of one schema with another – show that neither the Fenaroli nor the Ponte, as an individual pattern, is ever preceded by the Quiescenza.Footnote

57

As the table shows, they both issue frequently from the ‘Converging Cadence’, a specific type of half close with a ![]() –♯

–♯![]() –

–![]() bass, often paired with a descending (‘converging’) line in contrary motion,

bass, often paired with a descending (‘converging’) line in contrary motion, ![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() . This specific collocation is seen in the Cimarosa sonata (Example 5), which suggests that Gjerdingen's documented usage of the Fenaroli and Ponte as individual patterns is a consequence of more general form-functional properties shared by the Fenaroli-Ponte hybrid. As seen in every example discussed above that precedes k279, the Fenaroli-Ponte is a dominant-grounding pattern, which follows directly from a half close or dominant arrival. And this same standing-on-the-dominant function is found in the Cimarosa keyboard sonatas on the whole, which are roughly contemporary with k279 (so far as we know, they date from the 1770s)Footnote

58

and replete with the same Italianate, galant phrasing found in Mozart. Twenty examples of the Fenaroli-Ponte are contained in these eighty-eight single-movement works, outlined in the accompanying Appendix: every one is used as a standing on the dominant, either in a postcadential capacity, after the articulation of a half cadence that expands said cadence (sixteen instances, as found here in Examples 3, 4, 5 and 7a), or, less often, initiating a less stable dominant arrival with a V7 or cadential 6

4 that leads to a complete dominant caesura (four instances, as found here in Example 7b). The Quiescenza, on the other hand, is a tonic-grounding ‘stock contrapuntal pattern’ that Hepokoski and Darcy call the 8–♭7–6–7–1

circumambulatio.Footnote

59

Both Quiescenza and Fenaroli-Ponte are postcadential formulas, but the former expands a tonic cadence, while the latter expands a dominant one. Mozart's juxtaposition of the two patterns therefore creates a grammatical impropriety at the level of formal functions: two conflicting suffixes, or, in Caplin's terms, two competing ‘after-the-end’ formulas (Example 8).Footnote

60

. This specific collocation is seen in the Cimarosa sonata (Example 5), which suggests that Gjerdingen's documented usage of the Fenaroli and Ponte as individual patterns is a consequence of more general form-functional properties shared by the Fenaroli-Ponte hybrid. As seen in every example discussed above that precedes k279, the Fenaroli-Ponte is a dominant-grounding pattern, which follows directly from a half close or dominant arrival. And this same standing-on-the-dominant function is found in the Cimarosa keyboard sonatas on the whole, which are roughly contemporary with k279 (so far as we know, they date from the 1770s)Footnote

58

and replete with the same Italianate, galant phrasing found in Mozart. Twenty examples of the Fenaroli-Ponte are contained in these eighty-eight single-movement works, outlined in the accompanying Appendix: every one is used as a standing on the dominant, either in a postcadential capacity, after the articulation of a half cadence that expands said cadence (sixteen instances, as found here in Examples 3, 4, 5 and 7a), or, less often, initiating a less stable dominant arrival with a V7 or cadential 6

4 that leads to a complete dominant caesura (four instances, as found here in Example 7b). The Quiescenza, on the other hand, is a tonic-grounding ‘stock contrapuntal pattern’ that Hepokoski and Darcy call the 8–♭7–6–7–1

circumambulatio.Footnote

59

Both Quiescenza and Fenaroli-Ponte are postcadential formulas, but the former expands a tonic cadence, while the latter expands a dominant one. Mozart's juxtaposition of the two patterns therefore creates a grammatical impropriety at the level of formal functions: two conflicting suffixes, or, in Caplin's terms, two competing ‘after-the-end’ formulas (Example 8).Footnote

60

Figure 2 Schema collocations in a galant corpus, from Robert O. Gjerdingen, Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 372

Example 8 k279/i, Allegro, bars 10–16. Grammatical impropriety and ellipsis in Mozart's usage of the Fenaroli-Ponte: two competing Anhänge

The upshot of this is a syntactical elision at a broader level of syntax: sonata ‘punctuation form’ (interpunctische Form), as it was described in eighteenth-century compositional treatises. In writings by Johann Mattheson, Johann Adolph Scheibe, Joseph Riepel, Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg, Johann Philipp Kirnberger and Heinrich Christoph Koch, all phrase constructions, at all levels of organization, are explained in an end-oriented manner.Footnote 61 Koch described these different types of punctuation as variously marked ‘resting points of the mind’ (Ruhepuncte des Geistes): ‘a composition can be broken up into periods [Perioden, Koch's term for large-scale sections like a sonata-form exposition] by means of [the] Ruhepuncte des Geistes, and these [Perioden], again, into single phrases [Sätze], and melodic segments [Theile]’.Footnote 62 Mozart's elision in k279 is targeted specifically at the phrase (Satz) level of punctuation in Koch's (and Riepel's) sense, as a cadence-oriented segmentation at the middleground that contributes to the larger-scale form. Sätze that close with tonic harmony and a perfect cadence go by the name Grundabsatz (‘I-phrase’), and Sätze that are directed at dominant harmony or a half cadence are called Quintabsatz (‘V-phrase’). The scripted succession of these Sätze builds to a large-scale level of syntax, because their ‘caesuras’ (Cäsuren) carry greater structural weight, or are more heavily ‘marked’. Koch termed them ‘principal resting points of the mind’ (Hauptruhepuncte des Geistes),Footnote 63 and maintained that only these Satz-affiliated caesuras within a Periode share in the ‘collation of phrases by means of punctuation’ (interpunctischen Vergleichung der Sätze).Footnote 64 This Vergleichung of Sätze and their attendant Hauptruhepuncte gives rise to larger-scale ‘punctuation forms’ such as ‘sonata form’ (die Form der Sonate) and ‘concerto form’ (die Form des Concertes), as they were discussed in Johann Georg Sulzer's Allgemeine Theorie der schönen Künste (1771–1774) and the third volume of Koch's Versuch (1793).Footnote 65 Each ‘punctuation form’ is a ‘periodic structure’ (Periodenbau) that depends on the alternation of Grundabsätze, Quintabsätze and Cadenzen.Footnote 66 This last term Koch reserved for a particular Hauptruhepunct: the perfect authentic cadence produced by the Schlußsatz (‘closing phrase’, meaning the subordinate or second theme) that closes a Hauptperiode, such as a sonata-form exposition or recapitulation.Footnote 67 Only this Cadenz may close a Periode, and is one of two most structurally weighty cadences within the sonata ‘script’.Footnote 68 The other is a medial half cadence produced by an internal Quintabsatz (in other words, ending a transition), which divides a Hauptperiode into two halves. Later, in his Musikalisches Lexicon of 1802, Koch would explicitly fix the structural weight of this Quintabsatz relative to the Cadenz of the Schlußsatz by designating it a Halbcadenz.Footnote 69 These two Hauptruhepuncte, the Cadenz and Halbcadenz, are equivalent to the ‘generically obligatory cadences’Footnote 70 that underlie Hepokoski and Darcy's sonata theory: the Cadenz marks the ‘essential expositional closure’ (EEC) and ‘essential structural closure’ (ESC) of an exposition and recapitulation respectively, while the Halbcadenz is synonymous with the ‘medial caesura’.Footnote 71

The Fenaroli-Ponte played a designated role in communicating this period structure of ‘punctuation form’. The more structurally weighted Sätze and Hauptruhepuncte, like all formal divisions and Ruhepuncte des Geistes, are expressed by hierarchically discrete syntactic processes, which Koch variously termed ‘punctuation formulas’, ‘punctuation figures’ and ‘punctuation signs’ (interpunctische Formeln, interpunctische Figuren and interpunctische Zeichen).Footnote 72 These formulaic signs are outlined as one of ‘two main characteristics … through which … the various sections in musical works [that] compose their periods … distinguish themselves as divisions of the whole…. The endings of these sections are certain formulas, which let us clearly recognize the more or less marked resting points…. [W]hat is important for all of these divisions is the formula through which they become marked as resting points, or, to use our chosen term, their punctuation sign [Zeichen].’Footnote 73 The Fenaroli-Ponte is precisely such a formula or sign, one strongly affiliated with the articulation of Quintabsätze, but after the caesura's punctuation, as a ‘suffix’. Any Ruhepunct may be given continued expression after the fact, through a specific punctuation formula that Koch termed an ‘appendix’ (Anhang): an ‘explanation … which further clarifies the phrase [Satz]’, and a ‘means through which a phrase['s] … substance [is] more closely defined’.Footnote 74 As noted earlier, the Fenaroli-Ponte examples in the Cimarosa sonatas cited in the Appendix are almost exclusively used as such an Anhang, and specifically to a Quintabsatz. But more importantly, these Fenaroli-Ponte Anhänge customarily served a particular Hauptruhepunct in the sonata punctuation script: in fourteen of the twenty-one examples in Cimarosa's sonatas, the schema functions as an Anhang to the medial Halbcadenz. The Fenaroli-Ponte is thus something of a transition-suffix, placed after the half cadence that structurally divides an exposition into two halves. The Halbcadenz of the recapitulation is the larger formal setting for the Cimarosa sonata shown in Example 5. In Hepokoski and Darcy's terms, the schema is a ‘dominant lock’ that expands the half close encountered around the moment of the medial caesura,Footnote 75 ‘a special prolongational technique that extends and “holds in place” the HC-arrival effect [of a transition] for a specific rhetorical purpose’.Footnote 76

This practice was not limited to Cimarosa, however. The excerpt from Schobert's Quartet Op. 7 No. 1 given in Example 4 occurs in the same Halbcadenz context, and the practice was otherwise very common in the music of Mozart's well-known Central European influences in the 1760s and 1770s, including Emanuel Bach, Johann Christian Bach, Josef Mysliveček, Josef Antonín Štěpán, Haydn and Johann Eckard, along with Schobert.Footnote

77

More than one hundred examples of the Fenaroli-Ponte from 1759 to 1802 are enumerated in the accompanying Appendix, which registers another sixty-one instances of its Halbcadenz usage in the music of these composers and later Mozart, alongside the fourteen Cimarosa versions already referred to. This sonata-form Halbcadenz usage appears to have been a rather stable late eighteenth-century practice: Schobert's Keyboard Concerto in F major, Op. 11 (1765), uses two different Fenaroli-Pontes in succession to highlight the Halbcadenz produced at the end of the soloist's transition, the first of which is shown in Example 9a. The same usage appears in mature Beethoven, who employs a Fenaroli-Ponte in the three transitions of the C minor Fortepiano Concerto of 1800, Op. 37, first movement, and twice again, as late as 1802, in those of the Second Symphony (Appendix, Beethoven Nos 3, 4, 6, 7, 9).Footnote

78

The last of these, given in Example 9b, features the characteristic Trommelbass accompaniment and the (quasi-)canonic primary lines, again realized as a soprano–tenor exchange. It also shows Beethoven's predilection for fitting the schema with a more elaborated ‘Durante countermelody’ ([![]() ]–

]–![]() –

–![]() –[

–[![]() ]–

]–![]() –[

–[![]() ]–

]–![]() –[

–[![]() ]),Footnote

79

also featured in the C minor Concerto.Footnote

80

Riepel's characterization of the schema as a ‘Ponte’ (‘bridge’) may owe in part to this customary form-functional usage: the schema's definition depends as much on its behaviour as on its internal structural features.Footnote

81

Indeed, some Fenaroli-Ponte variants exhibit the same Halbcadenz postcadential function, though slightly altered in terms of their structure. In keyboard writing especially, the bass pedal is often registrally implied between the two half cadences that frame the schema, recalling Hepokoski and Darcy's definition of a ‘dominant lock’ as an ‘actual or implied dominant pedal-point’.Footnote

82

Such is the case with Emanuel Bach's Flute Trio in C major, Wq87, from 1766 (Example 10), probably known to the Mozarts by the early 1770s (given Mozart's letter to Breitkopf discussed above). Bach's setting features a nearly identical descant as the Fenaroli-Ponte in k279: semiquavers dressed with trills.Footnote

83

]),Footnote

79

also featured in the C minor Concerto.Footnote

80

Riepel's characterization of the schema as a ‘Ponte’ (‘bridge’) may owe in part to this customary form-functional usage: the schema's definition depends as much on its behaviour as on its internal structural features.Footnote

81

Indeed, some Fenaroli-Ponte variants exhibit the same Halbcadenz postcadential function, though slightly altered in terms of their structure. In keyboard writing especially, the bass pedal is often registrally implied between the two half cadences that frame the schema, recalling Hepokoski and Darcy's definition of a ‘dominant lock’ as an ‘actual or implied dominant pedal-point’.Footnote

82

Such is the case with Emanuel Bach's Flute Trio in C major, Wq87, from 1766 (Example 10), probably known to the Mozarts by the early 1770s (given Mozart's letter to Breitkopf discussed above). Bach's setting features a nearly identical descant as the Fenaroli-Ponte in k279: semiquavers dressed with trills.Footnote

83

Example 9a Fenaroli-Ponte, customary sonata-form usage as transition-suffix: Schobert, Keyboard Concerto in F major, Op. 11/i, Allegro (1765), bars 71–82 (Paris: author, 1765). Bibliothèque Nationale de France <http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9063031f.r=johann+schobert.langEN>

Example 9b Fenaroli-Ponte, customary sonata-form usage as transition-suffix: Beethoven, Symphony No. 2, Op. 36/i, Adagio molto – Allegro con brio (1802), bars 235–244 (Neue Beethoven-Gesamtausgabe, section 1, volume 1, Symphonien, ed. Armin Raab (Munich: Henle, 1994). Used by permission

Example 10 Fenaroli-Ponte, customary sonata-form usage as transition-suffix: Emanuel Bach, Trio in C major, Wq87 (h515)/iii, Allegro (1766), bars 17–28 (Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: The Complete Works, series 2, volume 3.2, Keyboard Trios, ed. Steven Zohn (Los Altos: Packard Humanities Institute, 2010)). Used by permission

This form-functional usage of the schema is the larger context for Mozart's employment of the Fenaroli-Ponte in the exposition of k279. The syntactic deviation at the local form-functional level is strategically targeted at the Halbcadenz, used to unsettle the Fenaroli-Ponte's normative sonata-form usage to communicate this Hauptruhepunct in the larger ‘punctuation form’. The situation is very similar to Mozart's syntactic game in the letter to Nannerl from 1774. The Fenaroli-Ponte, as an Anhang, is a closing gesture that enters too early, the musical equivalent of Mozart's premature use of the closing salutation ‘lebe wohl!’, which obscures the punctuation of the entire sentence. The premature entry is quite audible as Mozart recontextualizes the leading note in the upper voice at bar 14: the penultimate stage of the Quiescenza becomes the first stage of the Fenaroli-Ponte (see the overlapping brackets in Example 8). The punctuation of a medial Halbcadenz is suppressed as a consequence of this elision, which can be seen most clearly when compared with the hypothetical recomposition of the passage given in Example 11 (audio file available as supplementary material at <>). This draws on the normative use of the schema reconstructed above, as well as Koch's techniques of phrase expansion and alteration as they apply specifically to Anhänge. To situate the Fenaroli-Ponte in a proper postcadential setting requires a transformation of the preceding Quiescenza, the tonic Anhang, into a Quintabsatz, which Koch discusses in volume 3, section 59 of the Versuch: an Anhang to a Grundabsatz may close with a half cadence, thereby giving a different sense of punctuation and tonal meaning to the entire span of the phrase. The Grundabsatz and its Anhang thereby acquire ‘the value of a Quintabsatz’.Footnote 84 This is a common technique for a transition, known in modern Formenlehre as a ‘dissolving P-Codetta’ or ‘false closing section’.Footnote 85 In the recomposition of Example 11, the transformation is achieved rather economically, by incorporating a brief Ti–Do–Sol Halbcadenz that Marpurg discusses in volume 2 of his Kritische Briefe über die Tonkunst (1763),Footnote 86 realized in an open-octave texture similar to the transition of k283, first movement, bars 16–22. The dominant of the Fenaroli-Ponte is now repositioned as a proper cadential arrival, restoring the schema's normal function as an appendix that reinforces and reiterates the medial-caesura half cadence. In Mozart's original, however, the elision results in two successive Anhänge, one a tonic expansion, the second a dominant expansion that ‘hangs’ onto nothing – its dominant anchor, the Halbcadenz, having been suppressed.Footnote 87

Example 11 k279/i, Allegro, bars 10–16, hypothetical recomposition: customary sonata-form and form-functional usage of Fenaroli-Ponte as transition-suffix restored (based on Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 9, volume 25/1, Klaviersonaten Band 1, ed. Wolfgang Plath and Wolfgang Rehm (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1986)). Used by permission

When dislocated to the second theme in the recapitulation of k279 (Example 12), the Fenaroli-Ponte becomes a superfluous addition that disrupts the latter of the two primary Hauptruhepuncte in the sonata script: the Cadenz. This second sonata-form deviation reflects the fact that in those rare cases where P or TR material appears in the context of S, it represents what Hepokoski and Darcy call an ‘intervention’.Footnote 88 The intervention here consists of disturbing a cadential punctuation formula of tonic orientation with a postcadential formula of dominant orientation: once again a syntactic non sequitur at the local level corresponds to an illicit use of a punctuation sign at the large-scale sonata level, except here the disruption is not elliptical but parenthetical. The Fenaroli-Ponte is inserted midway through a typical cadential sequence of schemata. Preceding its unexpected re-entry at bar 84 is a schema string composed of an Indugio, Long Comma and Passo Indietro, which often functions as a larger ‘punctuation formula’ preparing an authentic tonic cadence, and, in this sonata-form location, specifically the Cadenz.

Example 12 k279/i, Allegro, bars 81–92, Fenaroli-Ponte: parenthetical disruption of the Cadenz

This cadential script can be seen in a partimento from Giovanni Paisiello's Regole reproduced in Figure 3. The Passo Indietro was often combined with its inverse, the Comma (the same pattern with outer voices flipped), producing a larger cadential collocation. This is featured prominently, for example, in Haydn's String Quartet in G major Op. 9 No. 3 (Example 13). The Comma and Passo Indietro, as more localized clausulae, here serve both to delay and to anticipate the Cadenz at bar 78: they target and prolong the I6 chord (bar 71) that Caplin calls a ‘conventionalized sign’Footnote 89 for an imminent ‘expanded cadential progression’, which was known in eighteenth-century theory as a cadenza lunga (long cadence).Footnote 90 In k279, the Fenaroli-Ponte interrupts the Cadenz mid-process, by recontextualizing an expected bass e of a Passo Indietro as a tenor e1 (bar 84) within the dominant lock of the Fenaroli-Ponte – an expected I6 becomes a dominant-embellishing I6 4. That the schema's parenthetical use was intended to be disruptive is unmistakable in the voice-leading discrepancy that results between the two schemata: the subdominant scale degree of the Passo Indietro's dominant 4 2 chord, the f heard on the eighth semiquaver of the bar, should move to an e for proper voice-leading resolution, yet registrally it moves to the Fenaroli-Ponte's g heard on the sixth quaver of the bar.Footnote 91 There is no harmonic progression between the two patterns, but rather a succession from V4 2 to 6 4. The disruptive nature of the schema's re-entry perhaps becomes most palpable where, following the dominant caesura of bar 86, the music continues with the cadential formula initiated in bars 82–84 (Example 12). It proceeds as if unaware of the events of bars 84–86, following its normal course as set out in the exposition, with no hint of ‘correction’.

Figure 3 Cadential script: Giovanni Paisiello, Regole per bene accompagnare il partimento (St Petersburg, 1782), 51; reproduced in Gjerdingen, Music in the Galant Style, 170

Example 13 Scripted Cadenz: Comma – Passo Indietro – Cadenza Composta: Haydn, String Quartet in G major Op. 9 No. 3/i, Allegro moderato (c1769–1770), bars 69–81 (Joseph Haydn Werke, series 12, volume 2, Streichquartette, ed. Georg Feder (Munich: Henle, 1963)). Used by permission

The Fenaroli-Ponte's deviant use consequently remains unresolved within the boundaries of the first movement. There is no realignment of the schema in the recapitulation. It displays, in Caplin's terms, a type of ‘illogical formal dissonance’.Footnote 92 It is only in the sonata's finale that Mozart restores its normative usage, with regard to local- and large-scale syntactic functions. Both in the first and third Hauptperioden (bars 18–22 and 104–108), the Fenaroli-Ponte clarifies the medial Halbcadenz as an appendix to a Quintabsatz produced by a Converging Cadence (Example 14). But in the opening Allegro, it is never at home – an illicit punctuation sign that disrupts the two primary moments of punctuation in the sonata form script represented by the Halbcadenz and Cadenz. The Fenaroli-Ponte is simply incapable of finding its feet in this Allegro movement.

Example 14 k279/iii, Allegro, bars 17–22: Fenaroli-Ponte sonata-form usage restored (Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 9, volume 25/1, Klaviersonaten Band 1, ed. Wolfgang Plath and Wolfgang Rehm (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1986)). Used by permission

SEMANTICS: FIGUREN, TOPOI, ‘WITZ’ AND MIDDLE COMEDY

Much like the grammatical play in Mozart's letter to Nannerl of 1774, there is no resolution to the syntactic problem in the opening Allegro. Both occurrences of the Fenaroli-Ponte are presented ‘arseways’: too early in the first Hauptperiode, too late in the third. Yet the customary sonata-form usage of the schema affords – like the grammatical conventions of language – an opportunity for witty expression. In the world of late eighteenth-century music theory and aesthetics, Mozart's elliptical and parenthetical disruptions of sonata-form syntax are expressive ‘figures’ (Figuren) for attracting a listener's attention. The celebrated music historian, theorist and aesthetician Johann Nikolaus Forkel discussed several such ‘figures for the attention’ (Figuren für die Aufmerksamkeit), including communicative devices such as ‘ellipsis’ (Ellipsis) and ‘suspensio’ (Suspension, Aufhalten), which create ‘unexpected turns and sudden transitions’ (unerwartete Wendungen und plötzliche Uebergänge).Footnote 93 Kirnberger described the figure of ‘parenthesis’ (Parenthese),Footnote 94 in particular, as introducing ‘something foreign that attracts the attention in a special way’.Footnote 95 These ‘figures of the attention’ in eighteenth-century theory and criticism were something of a blanket category that encapsulated various forms of musical expression in general. For example, the lexicographer, grammarian and philologist Johann Christoph Adelung outlined, among those for the ‘attention’, figures for the ‘imagination’, ‘emotions’, ‘passions’, ‘wit’ and ‘acumen’ (Aufmerksamheit, Einbildungskraft, Gemüthsbewegungen, Leidenschaften, Witz and Scharfsinn).Footnote 96 And Forkel's own figures for the attention, influenced by Adelung's aesthetics, dwelled extensively on the particular variety of ‘figures for the imagination’.Footnote 97 Along with Forkel and Kirnberger, Mattheson, Scheibe and Koch also described a variety of techniques for playing with convention (later eighteenth-century appropriations of baroque Figurenlehre), which served to create unexpected twists. These were the source of higher, metaphorical forms of communication, like wit, humour, awe, the serious and the sublime, as described in a series of theoretical and aesthetic writings from the later part of the eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries. Koch, for example, cites the ‘unexpected’ (das Unerwartete) as a means of ‘arousing attention’ (Aufmerksamkeit zu erregen), whether for the expression of the ‘playful’ or ‘jocular’ (Scherzenden), or of the ‘sublime’ (Erhabne).Footnote 98

The ‘playful’ or ‘jocular’ nature of Mozart's deviations is communicated by the affective significance of the musical topics that frame them. The intended expression for ‘unexpected’ twists in the musical discourse was regulated by the musical affects associated with certain styles and genres, as discussed in the writings of Mattheson, Scheibe, Sulzer and Koch.Footnote 99 The social meanings embedded in these musical topics allowed for the plotting of a particular gesture on a semiotic axis or grid (light versus heavy, comic versus serious, and so forth).Footnote 100 As Koch relates it, ‘the composer can most clearly differentiate for the hearts of his listeners … the sublime [Erhabne] from the playful [Scherzenden]’.Footnote 101 Musical topics were the extramusical contexts and situation-defining frames that ‘semanticized’ a particular figure for the attention, particularly if the figure is accompanied by a shift in topical discourse.Footnote 102 For example, in the Fortepiano Concerto k449 in E flat major, from 1784, Mozart once again employs the figure of ‘parenthesis’ (Parenthese) to disrupt the Cadenz in the recapitulation (Example 15), as he did in k279. Bars 317–3191 set up strong expectations for a perfect authentic cadence with a cadenza lunga cast in a bravura style, complete with the soloist's cadential trill as a sign for the imminent cadence. The caesura is powerfully diverted with a deceptive motion to the submediant, preceded by its own dominant, on beats 2–3 of bar 319, with B♭ ascending to B♮. Not only is the entrance of C minor's dominant metrically syncopated, but this change of harmony and tonal orientation is accompanied by a marked change in dynamics and orchestration, to forte and tutti, stating the dominant in a most assertive root-position form. These features highlight the syntactic deviation with a discrete change of musical affect – the figure is framed by a tempesta or Sturm und Drang topic, which produces a frisson of awe and shock.Footnote 103 Such violations were of course equally associated with comical, humorous or witty effects, which figured in contemporary writings as prominently as discussions of the musical sublime and the serious. The entry ‘Comisch’ first appeared with reference to instrumental music in Sulzer's fourth edition of the Allgemeine Theorie der schönen Künste (1792–1794);Footnote 104 and the broad category of the ‘humorous’, discussed both in terms of Witz (wit) and Laune (humour) in contemporary German writings, remained a subject of discussion in important publications by Koch, Friedrich August Weber, Rochlitz and Christian Friedrich Michaelis.Footnote 105 The running theme in these essays is that, as Weber described it, ‘comical characteristics and caricatures’ are created by ‘departure from the usual rules’.Footnote 106

Example 15 Mozart, Fortepiano Concerto in E flat major k449/i, Allegro vivace (1784), bars 317–321: parenthetical disruption of the Cadenz by an intrusive tempesta topic (Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 5, volume 15/4, Klavierkonzerte Band 4, ed. Marius Flothuis (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1975)). Used by permission

The Fenaroli-Ponte deviations in k279 are framed within this broader context of musical comedy and humour: Mozart's syntactical elision and parenthesis are topically ‘marked’, or ‘semanticized’, as in k449, but are a much lighter affair, combining features of musical ‘wit’, ‘parody’ and ‘caricature’ with a particular species of the humorous that August Weber called ‘artfully imitated bungling’. This element is suggested by Mozart's use of a topic of ‘instrumental mimicry’ (Instrumentalmimik), again Weber's term.Footnote 107 Most simply, the topic is a parody of musical performance, one that enacts a mindless or overenthused performer, often coupled with the image of an inept composer: the inept composer-performer. Danuta Mirka's own discussions of the topic describe the ‘[mindless] repetition of a single figure taken from the stock repertory of eighteenth-century finger exercises’ as a means of producing ‘metric manipulations’, and these in turn as a means of conveying the ‘artfully imitated bungling’ of a composer, ‘an imaginary [composer-]performer losing the sense of meter in a display of virtuosity’.Footnote 108

Mozart's communicative strategy in k279 similarly adopts this ‘most sophisticated species of the musically humorous’,Footnote 109 with manipulations directed at the norms of galant phraseology and sonata-form punctuation. The mindless ‘repetition of a single figure taken from the stock repertory of eighteenth-century finger exercises’ is seen in the inclusion within the Fenaroli-Ponte of what Daniel Gottlieb Türk called a Trillerkette (chain of trills).Footnote 110 This normally occurs within a phrase or schema boundary, typically as an embellishment of an expanded harmony: the first example extracted from Türk's volume in Figure 4 (top staff) shows it outlining the span of an octave; in the second example (bottom staves), the embellishment is actually illustrated with a Fenaroli-Ponte. The Trillerkette appears to have been a surface feature of the schema, as displayed for instance by Example 10, and in k279 functions as something of a grouping mechanism – it causes the ear (retrospectively at least) to group the trilled B at bar 142 with the following trilled notes C, D, E and F at bars 143–153 (refer again to Example 8). This usage, however, is unconventional, as the Trillerkette crosses a phrase division: it begins as a ‘cadential trill’, in the context of a Quiescenza, which is carried across the boundary of the phrase and into a different schema. The trill is assimilated into the Fenaroli-Ponte, so that the mindless repetition of the embellishment is coextensive with the grammatical error that obtains in the succession from a Quiescenza to a Fenaroli-Ponte: the cadential trill should have ended with a resolution of the Quiescenza, as in the hypothetical recomposition shown in Example 11. The cooperation of these faux pas underlying Mozart's use of the Trillerkette (mindless repetition of trills) and Fenaroli-Ponte (break in schema syntax, suppression of a Halbcadenz) betrays features of what Koch described as musical representations of an ‘absent-minded person’, an absent-minded composer-performer: ‘How … does a composer represent an absent-minded person in an instrumental piece? … [H]e connects sections which do not properly belong together.’Footnote 111 The overall improvisatory character of the Allegro was seemingly staged to enact the bungling composer-performer, perhaps in an extemporizing setting, giving further meaning to John Irving's contention that, in attempts to discern whether ‘Mozart ha[d] an express intention[,] … reading the opening pages of K.279 as a texted version of something spontaneous is a good start’.Footnote 112

Figure 4 Trillerkette: Daniel Gottlieb Türk, Klavierschule (Leipzig and Halle, 1789; facsimile edition, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1962), chapter 4, 266

But the humour of k279 is neither of the farcical and absurd kind that Sulzer associated with the ‘low comic’ – more characteristic of Mozart's later ‘Musical Joke’, k522 – nor of the ‘serious’ and ‘tragic’ kind unique to the ‘high comic’. The gestures are more representative of the witty aspects Sulzer aligned with ‘middle comedy’.Footnote 113 k279's is a more crafted humour, seen especially in several features of Paradoxie (paradox), a ‘gift of musical wit’ (Gabe des musikalischen Witzes) that Weber saw particularly in the music of Mozart and ‘Papa Haydn’. This involves a ‘departure from the usual rules, whose observance at the same time … connects phrases into a whole, which, through this process, receives a layer of paradox … and ludicrousness of a lesser degree’.Footnote 114 In other words, the deviations are tempered, or mediated, in some way, creating the impression of an ‘artful’ bungling. As Sulzer described it, ‘middle comedy’ has a ‘fine wit’ involving ‘actions and customs of the genteel world … which the Romans called urbanity’.Footnote 115 In Leonard Ratner's words, the artful imitation of musical bungling ‘raises the clumsy to an artistic level’.Footnote 116

Mozart's own aesthetics, as conveyed in the letter to Leopold from Augsburg of 1777, which reports on his visit to Heiligkreuz, run along these lines: ‘one can be even more unusual and yet not offend the ear’,Footnote 117 he says in response to the excessive tonal wanderings of Friedrich Hartmann Graf's music. Such genteel customs can be seen in Mozart's careful stitching of the Fenaroli-Ponte with the Quiescenza that precedes it: its driving polyphonic lines create fluid linear connections with the preceding material, with scale-degree overlaps that compensate for the breaking of the schema collocation (see once more the overlapping brackets in Example 8). Beyond the careful stitching-together of galant phrases, which gives a contrapuntal fluency to the grammatical infelicities, another element of ‘paradox’ emerges in the second and most blatant deviation that parenthetically inserts the Fenaroli-Ponte into the second theme. This obvious dislocation and disruption were seemingly set up as a humorous way of realizing a convention in order to play with convention – namely, that of cadential deferral. Mozart may have anticipated that his listeners would expect the Cadenz along with some ploy for tinkering with that generic norm. Evaded or feigned cadences, known as cadenze finte in eighteenth-century theory,Footnote 118 were so common a ‘figure of the attention’ in the sonata punctuation script that one aspect of the aesthetic experience was to predict – to form expectations about – what particular device or solution a composer will choose for a given piece.Footnote 119 The Cadenz, put simply, afforded an opportunity for wit. The unexpected re-entry of the Fenaroli-Ponte in this context, unorthodox and humorous as it may be, nonetheless responds to the compositional issue of cadential deferral – a norm, of sorts, in its own right, as evidenced by the explicit category of a ‘feigned cadence’.

LISTENERS: KENNER UND NICHTKENNER, ZEITGENOSSEN UND NICHTZEITGENOSSEN

An oft-cited letter from Mozart to his father, dated 3 July 1778, reports on the success of a concert in Paris, which featured its namesake symphony in D major, k297, a composition roughly contemporary (1778) with the sonata k279. The symphony's good fortunes resulted, in part, from a witty turn of phrase that was tailored to the specific expectations of a Parisian audience:

The Andante and the Allegro finale also pleased, but particularly the latter, because I had heard that all finales here begin tutti, and usually in unison, and so I began with just two violins alone, playing softly for eight measures; then came a forte, followed at once by a piano, and all the listeners (as I expected) said ‘shhhhh’ at that moment. Then the forte came back, and when they heard that, the sounds of the forte and of the applause were one.Footnote 120

The same communicative strategy described for his ‘Paris’ Symphony is conceivably what Mozart had in mind for k279: both caricature a convention by calling attention to it with a flagrant deviation. In the symphony, the context which frames the deception belongs to a more regional dialect: Parisian finales began forte and tutti. In the sonata, the Fenaroli-Ponte's unorthodox grammatical usage comments on the ‘punctuation signs’ that produce and clarify the meaning of cadences in the sonata-form script. Yet the deceptions in k279 are a much more complicated affair, engaging numerous stylistic and generic aspects of phrase syntax, whereas the forte–tutti game in the ‘Paris’ symphony involves what Meyer called ‘secondary parameters’, which are syntax-independent.Footnote 121 The sonata's humour appears to have had a more sophisticated audience in mind. The dialogue between phrase-level schemata and a larger-scale sonata-form grammar seems to have been an attempt to satisfy a dual demographic of Liebhaber and Kenner audiences, by means of a ‘popular’ yet also ‘difficult’ style. The galant phrase-level patterns are like familiar ‘props’ for choreographing a syntactical game. A few years later, in a letter of 23 December 1782, Mozart would explicitly describe such a mediated strategy for the concertos k413–415:

These concertos are a happy medium between what is too easy and too difficult; they are very brilliant, pleasing to the ear, and natural, without being vapid. There are passages here and there from which the connoisseurs [Kenner] alone can derive satisfaction; but these passages are written in such a way that the less learned [Nichtkenner] cannot fail to be pleased, though without knowing why.Footnote 122

It is not difficult to imagine that Mozart's elision in k279 was influenced by Emanuel Bach's philosophies about musical listening in the Versuch, which the Mozart family knew well:Footnote 123 ‘There are many things in music which, not fully heard, must be imagined.… Intelligent listeners [verständige Zuhörer] replace such losses through the power of their imagination [durch ihre Vorstellungs-Kraft]. It is primarily these listeners whom we must seek to please.’Footnote 124 From this point of view, k279 appears to be a calculated recipe of galant idioms at the phrase level for Liebhaber and play with punctuation at the larger-scale sonata level for Kenner.

Aside from the artful imitation of a bungling composer, perhaps Mozart's ‘express intention’, to restate Irving's query, was an even more operatically minded, or ‘theatrical’, humour.Footnote

125

The composition of the set of six sonatas coincided with the writing of the opera buffa La finta giardiniera, which saw its first performance at Munich in 1775, where Mozart was also busy with epistolary mischief. Indeed, the various technical games with the Fenaroli-Ponte might conjure the image of a drunk or dim-witted character who consistently miscues. In the exposition, he stumbles onto the operatic stage too early (postcadential dominant enters prior to a half cadence or dominant articulation). Perhaps he tripped, or was caught on the garb (the trill) of the preceding Quiescenza and then dragged onto the stage inadvertently and prematurely: the repeated trills and Instrumentalmimik gesture may suggest this early entry and his stumbling. In the fused principal theme-transition of the recapitulation (Example 16), Mr Ponte enters at the right time but is wearing the ‘wrong’ costume: a Ponte is rightly employed here after a half close (bar 67), but is now masquerading as a different hybrid schema, a ‘Quiescenza-Ponte’. Mr Ponte is now dressed with the thematic material that initially belonged to Ms Quiescenza in the exposition: the ♭![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() line of the exposition (Example 8) is transformed into

line of the exposition (Example 8) is transformed into ![]() –

–![]() –♯

–♯![]() –

–![]() (Example 16). Recognizing his blunder, he dashes off the stage via the truncated, unfinished thought of bar 69 (Examples 1b and 16). Later in the recapitulation, he remembers to wear the proper attire (once again a Fenaroli-Ponte), but now enters far too late in the opera (second theme of the recapitulation, Example 12): Mr Ponte's part was over several scenes earlier.Footnote

126

(Example 16). Recognizing his blunder, he dashes off the stage via the truncated, unfinished thought of bar 69 (Examples 1b and 16). Later in the recapitulation, he remembers to wear the proper attire (once again a Fenaroli-Ponte), but now enters far too late in the opera (second theme of the recapitulation, Example 12): Mr Ponte's part was over several scenes earlier.Footnote

126

Example 16 k279/i, Allegro, bars 66–69: Ponte ‘masquerading’ as Quiescenza