Introduction

Over the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the world has witnessed three periods during which several governments took over the assets belonging to foreign investors operating in their territory. The first wave of expropriations took place in the 1920s and 1930s, when revolutionary governments expelled foreign firms (particularly in the energy sector) and replaced them with domestic state-owned firms.Footnote 1 The second and largest wave occurred in the 1960s and 1970s, when governments in Latin America and recently decolonized African and Asian countries took over the operations of major multinational corporations in the natural resource, infrastructure, and industrial sectors.Footnote 2 The third wave of expropriations took place in the early twenty-first century. Due to the historical approach of this paper, we do not analyze that wave but hope our taxonomy will provide analytical tools to understand it.Footnote 3 These very visible instances of economic nationalism against foreign investors have been widely researched in business history, political economy, and international business. While political economy and international business have sought to establish general theories that explain expropriations across time and space,Footnote 4 international business history has often focused on discrete instances of expropriations explaining the historical particularities of individual cases.Footnote 5

We argue that to conduct an expropriation of foreign private property, a government needs to build an alliance of different actors that expect to gain some rewards from the expropriation. We maintain that the nature of the alliance depends on several characteristics of the host country that include the longevity and legitimacy of the nation-state and the strength of organized labor. Our definition of the different types of political alliances contributes to existing explanations of when and why expropriations take place. Political alliances help us to understand how the expropriations take place in terms of the political strategies behind these actions. Based on our case narratives, we define three distinct types of alliances built to conduct expropriations of foreign property:

1. a political alliance between the government and the domestic organized labor,

2. a political alliance between the government and domestic business owners, or

3. a political alliance between the government and domestic civil servants.

We do not believe that this framework of different domestic political alliances that drive the timing and form of expropriations are exhaustive, but rather that they establish an important pattern that can only be seen by comparing the rich and detailed historical accounts of individual cases. We hope our paper can be a starting point for other studies defining other types of alliances with other constituencies.

We conduct our study through a comparative historiography approach. This means we draw on a synthesis of existing historical (and social-scientific) accounts in place of direct archival research. This approach was first advocated in 1958 by Fritz Redlich, in recognition of the valuable and reliable archival research that underpins historical research monographs. He questioned why historians would frown on the “systematic use of the resulting material, derisively called ‘secondary,’ [which] appears as somewhat absurd, when the goal is highly sophisticated synthesis and not a mere narrative.”Footnote 6 Business history in particular has relied on single case studies, with comparative or industry-wide research being less common. Similar concerns about the lack of structured approaches to synthesize the insights from individual studies, has led to the development of explicit approaches to synthesis in related research areas, such as meta-ethnography.Footnote 7

To our knowledge, few scholars have sought to explain the differences between full and partial expropriation, as well as nationalization versus indigenization.Footnote 8 Scholars have noted that economic nationalism may occur on a sliding scale ranging from punitive taxation, over local content requirements (e.g., domestic shareholding), to complete expropriations.Footnote 9 Others have focused on the timing of expropriation or which industries have been targeted.Footnote 10 However, we believe that there are important domestic political, social, and economic factors that influence how countries seek to enact expropriations that are relevant to understand their historical trajectories. To elaborate our point, we compare the history of seven countries in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa to show that expropriations followed different political agendas.

Due to the geographic and temporal range of our cases, we do not present primary archival research, which would be beyond the scope of an article. As historians, we believe in the value of primary archival research to obtain new knowledge of the past, but we also see a role for comparative historiography that allows us to build on the existing knowledge from multiple in-depth historical case studies across different regions.

The Expropriation of Foreign Property: Why, Where, and When

Existing explanations for the expropriation of foreign property mostly come from other social science disciplines, such as international business, international political economy, and international law. They mostly take a broader, more international view that aims to theorize the conditions under which states may take foreign property. These explanations converge around a set of reasons for expropriations listed in Table 1. Authors do not necessarily put forward a single explanation at the expense of all others, as becomes clear from the list below, but combine different reasons in their argumentation of why, where, and when expropriations occur.

Table 1 Explanations of expropriations.

Note: Compiled by the authors.

When trying to understand why developing countries expropriate foreign property, explanations have focused on abstract concepts such as ideology, symbolism, and fairness. For example, rulers who perceive that the country’s level of poverty is the result of a history of foreign exploitation might decide to ensure national control over “the commanding heights of the economy,” that is to say, over strategically important industries.Footnote 11 Kobrin, however, cautioned that ideology’s role as the main driver for expropriation only applies for the mass expropriations resulting from state takeovers led by Communists.Footnote 12 Another justification for expropriation may be based on the unwillingness of multinationals to renegotiate existing contracts that are perceived as unfair to the host country.Footnote 13

However, not all explanations perceive ideology or symbolism as key to decision making and instead assert that governments expropriated because they had gained the capability through acquisition of technology or because the international conditions were favorable to expropriations.Footnote 14 Most studies of expropriations, however, went beyond these general explanations of why this occurred toward taking into account the where and when as well.Footnote 15

Apart from the mass expropriations in Eastern Europe after World War II, most expropriations of foreign property in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have occurred in less developed or emerging economies. This has led many scholars to focus on where expropriations take place. Explanations broadly focus on (1) the industrial sector affected by the expropriation and (2) the institutional characteristics of the expropriating nation-state. Expropriations in the natural resource sector (including oil, mining, and agriculture) represented around 40 percent of all expropriations during the 1960s–1970s wave.Footnote 16 Although those expropriations garnered the most press coverage and prompted the most diplomatic tensions, that wave of expropriations also included a significant amount of expropriations in the manufacturing sector (27 percent) followed by finance (12 percent) and trade (5 percent).Footnote 17 In the great majority of the cases (90 percent), the expropriations were selective, as they targeted particular firms or industries.Footnote 18 The strategic importance of the sector for the expropriating country is key to understanding this pattern.

Many scholars have assumed that democracies are more effective at protecting foreign investors than autocratic states.Footnote 19 However, others have argued that in countries where political turnover is high (whether they are democracies or dictatorships), rulers will assume a short-term horizon in defining their actions and will be tempted to expropriate foreign firms and obtain the short-term gains from the expropriation without dealing with the long-term problems.Footnote 20 Ultimately, many scholars agree that expropriations are more likely to occur in countries with “weak institutions,” usually defined (as critics have pointed out) as not sharing the institutional framework of Western liberal democracies.Footnote 21

Using a neo-Marxist lens, the so-called dependency scholars studied expropriations as one of the tools used by peripheral countries’ dominant classes to reduce their subordinate role in the global economy. For Dos Santos, the expropriations of export industries that took place in Latin America in the 1930s and later on in the 1960s aimed to gain domestic control over the main source of hard foreign currency.Footnote 22 The rationale, according to Dos Santos, of these initiatives was to use this foreign currency to fund an industrialization process that would eventually break the expropriating country’s dependency status. By the very nature of how the world economic system works, Dos Santos posited, this end of the dependent status never materialized, but was replaced by another type of dependence. Evans confirms this point by showing how hard it was for the Brazilian bourgeoisie to control multinational corporations (particularly in research and development) while at the same time trying to increase the nation’s economic output.Footnote 23 Dos Santos added that in the 1960s and 1970s the peripheral bourgeoisie took advantage of what they perceived as a general weakening of the United States in the global sphere (reflected in the catastrophic Vietnam War) to either expropriate foreign property for their development programs or to take initiatives to collectively weaken the power of the multinationals with organizations such as OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) or the Non-Aligned Countries.Footnote 24 Regardless of any revolutionary language used by most expropriating governments, most dependency scholars agree with the idea that the working classes did not usually lead expropriations.Footnote 25

Studies addressing when expropriation is likely to occur focus on the technical characteristics of the expropriated firm or industry, the evolution of international prices of the product under foreign control, and general international trends in the political economy. Kobrin provides a simple explanation of the rationale of expropriation policies by arguing that, once the benefits of placing a particular industry in foreign hands no longer justify the costs and regulation involved, a government might find it more beneficial to expropriate.Footnote 26 Combining several of the previous elements in a single model, Medina, Bucheli, and Kim maintain that expropriation of foreign firms is more likely to take place when the host government has limited capability to monitor taxation (after all, taxation of several industries can be highly complex and requires particular know-how the local government might not have), its economy has acquired capabilities to run the industry, the host country’s economy does not depend significantly on exports controlled by foreign firms, and political competition is restricted.Footnote 27 Movements of international commodity prices can also account for industry-specific expropriations, for example, the link between high oil prices and oil company expropriations. This dynamic is frequently most evident in more autocratic host countries, combining a range of different reasons to account for these events.Footnote 28

In summary, existing explanations cover a wide range of reasons for expropriations, but even these do not fully explain all cases of expropriation. We maintain that closer attention to the specific national contexts and the convergence of domestic interest groups are important, yet undertheorized in terms of how expropriations occur. Our comparative historiography offers an alternative framework that is more responsive to the kind of contextual, contingent, and temporally unique features of expropriations in developing countries. We believe that historical research’s strengths in attending to the specific and unique in the analysis of historical events offers an alternative mode to creating theoretically relevant explanations.

Selecting Cases of Expropriation in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa

Our synthesis focuses on historical research on expropriations in developing countries in the mid-twentieth century, a period that saw a large number of expropriations. Expropriation is defined as a “governmental action to transfer the ownership of private (in this case, foreign) assets to the state, with or without compensation”Footnote 29 or “the forced divestment of equity ownership of a foreign direct investor.”Footnote 30 We consider cases in which the government forces the divestment of foreign-owned assets either to redistribute them among a particular domestic constituency (referred to as indigenization) or to be owned by the government (nationalization). In this study, we do not consider cases of “creeping expropriation,” defined as cases “when governments change taxes, regulation, access, and laws to reduce the profitability of foreign investment.”Footnote 31 We also distinguish between nationalization and indigenization as two different forms of expropriation that are usually lumped together.Footnote 32

For this article, we chose to discuss several paradigmatic cases of expropriation. The one taking place in Mexico in 1938 was the largest at that time outside the Communist world. Venezuela was a major oil producer in the 1970s and has previously led the creation of OPEC. The conflicts between the Chilean government and foreign firms eventually led to the establishment of one of the longest military dictatorships in the Americas. Ghana and Nigeria were the two most extensive cases of indigenization decrees. Zambia’s copper nationalization was seen as a response to the Chilean decrees, and Tanzania’s nationalizations in response to the Arusha Declaration was one of the few cases in Africa influenced by political ideology.

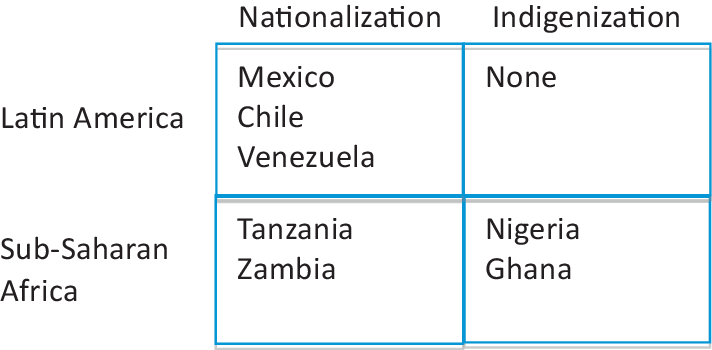

While nationalization means that the government expropriates and takes over shares and assets, in the case of indigenization the government enacts legislation that requires foreign investors to sell part or all of their shares or assets to a domestic owner. This was an important factor in our selection of cases, as we were interested in why governments would choose one form of expropriation over another. Indigenization-type expropriation was more common in sub-Saharan Africa, so we selected two well-known and significant cases (Ghana and Nigeria). However, sub-Saharan Africa also had well-known cases of nationalization, so we added Zambia and Tanzania for further comparison. We were not aware of any significant cases of indigenization in Latin America. All of these cases saw significant expropriations, by which we mean the size and scale of expropriations of foreign property were considered sizable at the time.Footnote 33 They also suggest having categories that differ on key dimensions, which for our cases are geography and type of expropriation (see Figure 1). Finally, we also considered whether there had been historical research on these cases for us to synthesize.

Figure 1 Case selection.

Note: Compiled by the authors.

We searched for literature on our cases based on prior knowledge, general historical accounts, hand-searching, and following up references. Historical research on our theme was rarely in the form of a stand-alone study or monograph solely dedicated to the subject, but rather formed part of other research controversies or a holistic account of a historical period. As a result, the terminology used by authors varied, making it difficult to conduct focused systematic searches through standard software tools. Ultimately, we selected studies that were either historical narratives based on archival sourcesFootnote 34 or by now historical accounts by social scientists at the time.Footnote 35 While most historiographical accounts follow established research controversies, our comparative historical analysis of our cases showed relatively little overarching debate or cross-citation. We compiled preliminary case histories for our seven cases, focusing on domestic political processes and actors in their explanations. We then compared within and across cases to develop analytically structured histories for comparison.Footnote 36

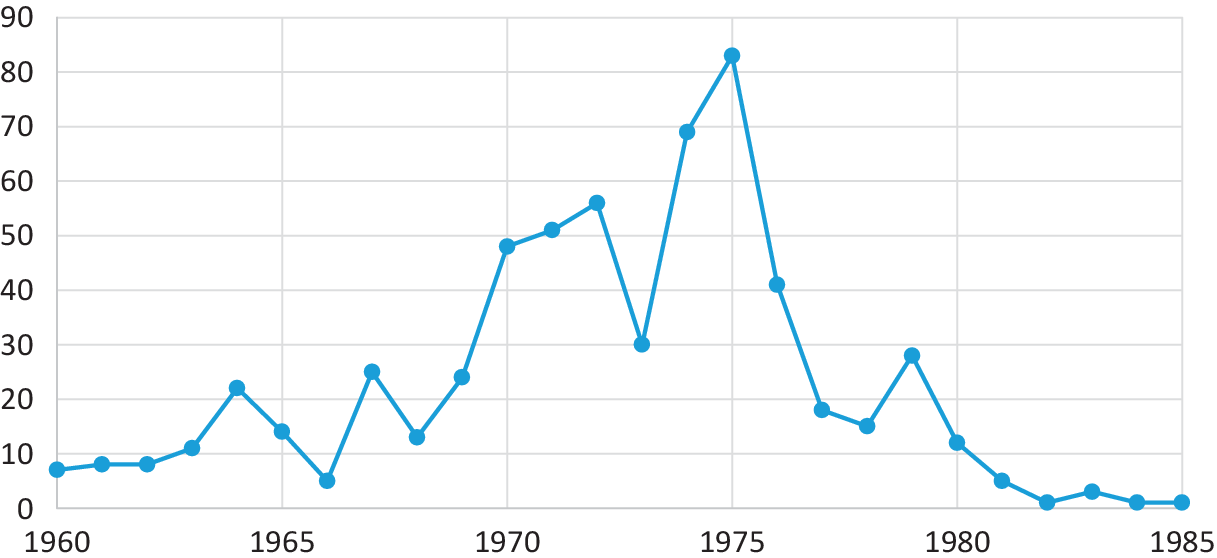

Expropriations of Foreign Property in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa

Expropriations in the twentieth century took place in two waves and mostly occurred in developing countries.Footnote 37 During the 1920s and 1930s, the most important events of the first wave took place in Latin America and Eastern Europe.Footnote 38 During World War II, the United States and their allies expropriated German property in their territories and, shortly after the end of the war, Soviet-occupied territories also expropriated both domestic and foreign property as part of their agenda of eliminating private property. During the early 1960s (the first years of the second wave), most expropriations took place in Asia, but from 1967 onward, the great majority of expropriations took place in Africa and Latin America (see Figure 2).Footnote 39

Figure 2 Expropriations of International Investments, 1960–1985.

Note: Compiled by Decker (Reference Decker2007).

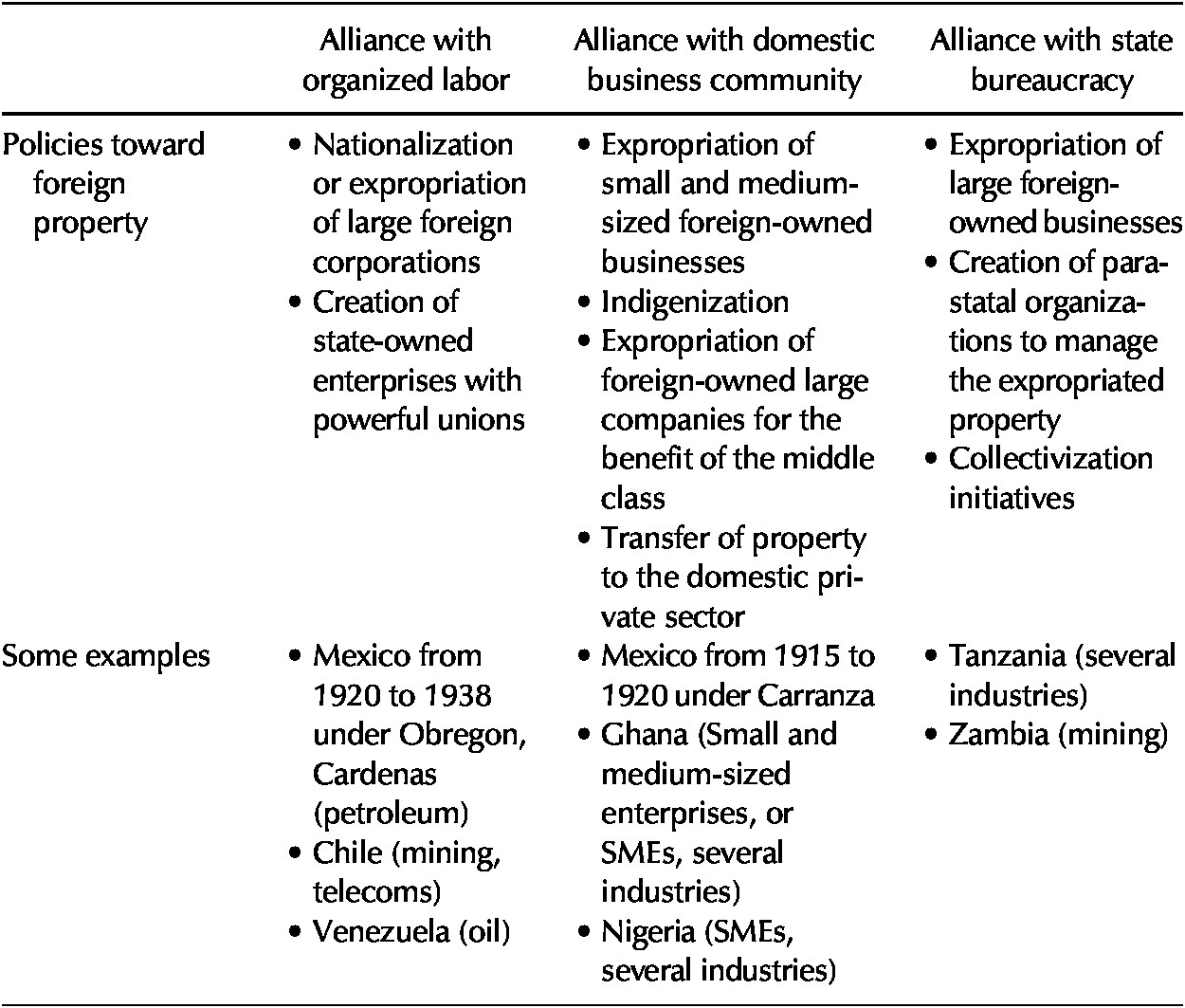

From our comparison between our seven cases, it became clear that different domestic groups supported nationalization or indigenization legislation. For the Latin American cases, the role of the labor movement stood out, but this was not the case in the sub-Saharan African countries. These also showed a marked difference in terms of the type of expropriation: indigenization decrees in West Africa were broadly supported by a more or less organized domestic business community, whereas nationalizations in East Africa appeared to be driven by different groups within the government or the ruling party. We structure our historical narrative to reflect these insights.

Government Alliances with Organized Labor

The labor movement has played a significant and active role in governments’ decisions to expropriate foreign-owned property in several countries. If the government’s alliance included the labor force working for the foreign firms and the workforce was sufficiently organized, the government responded to conflicts between labor and multinationals by supporting domestic workers, and not the foreign investor. These political alliances can shift over time, and policies toward foreign firms change accordingly. We find clear examples illustrating these changes in the case of the Mexican and Venezuelan oil industries and the Chilean copper industry.

The Mexican oil history constitutes a classic example of an expropriation resulting from changes in the government’s political alliance. General Porfirio Díaz ruled Mexico from 1876 to 1910. Díaz brought stability to the country after decades of political chaos and internal and external wars by ruling with an iron fist while simultaneously opening the doors to foreign investors. Díaz’s rule perfectly exemplified a regime supported by a small political alliance. He restricted political freedoms and created a system in which most economic rents were distributed among those belonging to his inner political circle: “Díaz realized that to co-opt potential opponents he needed to reward them with rents. He also realized that to generate those rents; he needed to promote investment. Promoting investment required that Díaz specify and enforce property rights as private, not public goods.”Footnote 40 Díaz achieved this through two means: by passing legislation that was very favorable to foreign oil companies and by creating a larger system in which the regional elites benefited from the operations of foreign corporations. The British oil firm Pearson and Son exemplifies how the system worked, as its board featured the most influential individuals in Mexico, including Díaz’s son.Footnote 41 During his rule, Díaz oversaw legislation that favored the operations of foreign corporations, including those operating in the oil sector. In short, the Díaz alliance included the foreign investors and segments of the national elite and excluded other groups of the Mexican society.

Events after 1910 suggest that the government’s winning alliance was changing concerning the political system created by Díaz. Frustrated at what they considered to be a policy that only benefited a small circle of Díaz’s friends, members of the Mexican elite overthrew Díaz. This action led to the widespread uprising known as the Mexican Revolution. In 1915, amid a civil war, a revolutionary faction led by Venustiano Carranza took power in Mexico City and launched a process to change the country’s institutional framework. His government was responsible for the 1917 constitution that granted the government legal rights over the country’s subsoil and for increased taxation of the oil multinationals, precisely when oil prices were rising sharply.Footnote 42 Even though this stopped short of expropriation, the multinationals considered these actions as confiscatory and the U.S. and British governments condemned the new legislation. These reactions clearly show that the alliance with foreign investors had been broken, and Carranza sought a new alliance with the domestic business elite. The constitution, however, remained unchanged. In 1920 Carranza was overthrown by one of his generals, Alvaro Obregón, who immediately faced strong resistance from some of the other members of the military who remained loyal to Carranza. Obregón responded by creating an alliance with peasants and labor unions. Under Obregón’s rule, a powerful labor federation was created (the Regional Confederation of Mexican Workers, or CROM in its Spanish acronym), which became crucial to ensuring his political survival.Footnote 43 Despite his approach to the labor unions, Obregón promised the United States that he would refrain from taking measures against U.S. oil companies in exchange for the neighboring country’s official recognition as Mexico’s legitimate president (a necessary gesture, as the civil war had not yet concluded). Tensions with the United States rose once again under Obregón’s successor between 1924 and 1934, as the government increasingly demanded greater concessions from the multinationals, again stopping short of expropriation. During this period, the productivity of the Mexican oil industry began to decrease, and the oil firms gradually started moving to the more productive oil fields of Venezuela, a country politically more accommodating to foreign investors.Footnote 44 Mexico’s rulers increased the size of their political alliance by approaching the national industrial elite while remaining allied to the co-opted labor unions. The government was building an alliance with domestic business owners, but not as a support for expropriation.

In 1934, Mexico elected Lázaro Cárdenas as president. It is in this phase that the shifting political alliances became favorable to expropriation. Cárdenas took power at a moment in which the country had finally achieved political stability and wanted to consolidate his party’s power by strengthening its ties with the labor movement. In 1938, oil workers went on strike, demanding higher wages. The multinationals refused, and the unions took the case to the Mexican Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the unions. When the multinationals refused to comply, Cárdenas decreed the complete nationalization of foreign oil property in Mexico. Taking control of the expropriated assets, the government created a state monopoly Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), which became an important base of support for Cárdenas’s government.

Changes in the size and composition of the Venezuelan government’s winning alliance also played a role in the nationalization of its oil industry in 1976. Contrary to the Mexican case, however, this initiative did not come from a left-wing party and did not face opposition from the U.S. government. Oil multinationals arrived in Venezuela in the 1920s during the dictatorship of Juan Vicente Gómez (1908–1935). Gómez repressed labor unionism and opposition parties while creating a favorable business environment for foreign oil firms. This meant that Gómez built a clear alliance with foreign direct investors. In 1918 he even invited the multinationals to write the oil legislation themselves. Gómez created a concession system under which many domestic landowners applied for concessions and then sold them to foreign firms, making handsome profits in the process. These individuals and families, together with the multinationals and members of the army, became Gómez’s political alliance and, during his rule, he accordingly managed the country’s economic policy to their benefit. Gómez died in 1935 while still in power.

Following Gómez’s death, Venezuela was ruled by military dictatorships until 1959 (with a brief pause when the center-left Acción Democrática Party, or AD, ruled between 1947 and 1948). During these years, the policy toward foreign oil firms consisted mostly of increasing taxes. The banned pro-democracy opposition argued that the resulting higher government income was used mostly to reward those close to the dictators. Venezuela returned to civilian rule in 1959 under an AD that shifted its original left-wing position to the center by increasing the budget for the military, promising to respect the property rights of the landowning elites, decreasing taxation, and slowing social reforms. Starting that year, Venezuela approved a series of laws that increased government participation in oil profits (forced partial nationalization) and limited the arrival of new foreign firms.Footnote 45 Social programs were funded by the taxes paid by foreign firms rather than the domestic private sector.Footnote 46 This shows that the previous alliance between the government and foreign investors was gradually breaking.

The main opposition party was the center-right COPEI (the Comité de Organización Política Electoral Independiente, also known as the Social Christian Party). After winning the presidential election in 1969 despite its right-wing leanings, the COPEI leadership also demonstrated openness to the idea of nationalizing the oil industry. By this time, Venezuela had a sizable middle class with the necessary technical skills to run the industry, a sophisticated industrial elite, and a stable democratic regime, meeting several of the preconditions for a government to be capable of expropriating and running a company or sector, as pointed out by DiJohn.Footnote 47 In 1970 the center-right COPEI nationalized the gas industry and announced complete government ownership of oil fields by 1983. This action showed that COPEI could not build a powerful enough political alliance for the 1974 elections without a nationalist platform. AD, however, still took power in 1974, but by that time, both parties agreed on the idea of domestic ownership of the oil industry, especially at a time when oil prices were rising sharply.Footnote 48 This step was taken in January 1976, when an AD Venezuelan government took control of the domestic oil industry and created the state-owned enterprise Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), turning foreign multinationals already present into contractors. Between 1977 and 1999, PDVSA played an important part in generating employment for the AD’s base while the AD also controlled the firm’s union, which had the power to mobilize voters in their favor.Footnote 49

Other expropriations were initiated by center or center-right regimes that had the support of a relatively large alliance composed of middle- and working-class supporters. In 1964 Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei was elected as president of Chile, and his constituency was composed of the middle class and some sectors of the working class distrustful of the left. Frei’s political platform included increases in welfare spending, protectionism, and the nationalization of the foreign-dominated copper and telecommunications industries, which were both in the hands of American multinationals: Anaconda, Kennecott, and Cerro Corporation for the copper industry and the International Telephone and Telegraph (ITT) for telecommunications. Frei opted for a policy he called the “Chileanization” (partial nationalization) of the copper industry, which aimed to increase domestic ownership to 51 percent after negotiations with the multinational Anaconda. This policy was developed in a context in which rising copper prices throughout the 1960s boosted revenues in that sector.

Additionally, as was the case for Venezuela in the 1960s, Chile had by this time developed its domestic capabilities to exploit this sector.Footnote 50 Frei also created a state-owned telecommunications firm to compete with ITT. These initiatives were widely supported by the middle- and working-class public and faced little opposition in Parliament.Footnote 51 In 1970 Marxist Salvador Allende won the presidential election, supported by a broad alliance composed of left-wing peasant and industrial labor unions, an important segment of the urban shantytowns’ population, and also attracting some middle-class supporters. Despite Allende’s ideological differences with his centrist predecessor Frei, economic nationalist policies continued to have strong popular support. Allende’s anti-imperialistic and Marxist discourse made expropriation consistent with his ideology. In 1971 Allende declared the expropriation of the properties of Anaconda, Kennecott, and Cerro to create the state-owned enterprise Corporación Nacional del Cobre (CODELCO), a few years before significant increases in copper prices. Later, in 1972, he expropriated ITT after discovering that the firm was involved in a scheme to overthrow him. It is worth highlighting that, despite the fierce opposition Allende faced from the Chilean center and right-wing parties, these two initiatives passed smoothly in the Chilean parliament.Footnote 52 Resource nationalism permitted Allende to have a wider agenda regarding expropriation in this particular industry than the one he could count on for other policies.

The examples in this section discuss cases of countries that undergo social, economic, and political transformations. This leads to a change from a regime supported by a small elite alliance that included the foreign investors to one that relies on a wider political alliance that includes the middle and lower classes (the latter usually participating in politics through powerful labor unions). To reward the members of their political alliance and ensure their loyalty, governments of both left-leaning and center-right-leaning orientation often took over the properties of foreign firms to establish job-creating state-owned enterprises and invest in areas of interest for their political alliances.Footnote 53 All these initiatives were supported by rhetoric that fused economic independence and national sovereignty. Although an alliance with organized labor was an important factor in making these expropriations possible, it did not necessarily translate into an increase of the welfare in general. Throughout the decades following the expropriations, the labor unions of both PDVSA and PEMEX were notorious for their corruption. In the Chilean case, the copper industry continued to be one of the main sources of income for the military, so it was not reprivatized.

Government Alliances with the Domestic Business Sector

Even though one would assume that the domestic private sector should oppose expropriation of foreign property on the grounds that domestic firms would see this action as a threat to their property rights, several scholars argue that a government can selectively protect property rights—ensuring that the property of a particular group will not be subject to expropriation.Footnote 54 This is most likely where domestic business has significant political influence. When a government’s main constituency is composed of domestic businesspeople in societies that offer limited political participation for the wider population, that government might either increase taxation on foreign firms or expropriate foreign property to redistribute rents among a segment of the private sector. Two West African cases highlight how expropriation via indigenization decrees aimed to legitimize the postcolonial national identity and citizenship.Footnote 55

The policies followed by the government of Ghana after independence in 1957 highlight the role of the domestic business community in the expropriation of foreign property. Ghana, the first British sub-Saharan colony to gain independence, began expropriations after its first head of state (Kwame Nkrumah) was overthrown in 1966 by an alliance of pro-Western police and military men. As a result of this turbulent political history, the expropriation programs fall into two distinct periods: an early phase from 1968 to 1969 and a later phase from 1972 to 1977. The “caretaker” regime that overthrew Nkrumah in 1966 returned the country to a short-lived democracy in 1969, which ended in 1972 after General Ignatius Acheampong and the military overthrew the government. In terms of the expropriation programs, the earlier decrees were minor and focused on resident foreigners, such as the Lebanese community. These were not foreign investors as understood in international business scholarship. The targeted groups were, rather, domestic investors with foreign nationalities. The fact that these groups were frequently the most affected by indigenization legislation suggests that these forms of expropriations were closely intertwined with contemporary struggles over citizenship in postcolonial Africa.Footnote 56 Major beneficiaries of the indigenization legislation were small African businesses that had felt threatened by the competition.Footnote 57

A somewhat different pattern emerges from Ghanaian expropriations after 1972, both regarding the motivations behind these policies as well as the firms that they targeted. In 1972 the partial nationalization of privately owned gold mines was announced; compensation for the 55 percent stake was negotiated by 1974. In other sectors, the government opted for indigenization instead of nationalization, which amounted to the forced sale of foreign business to domestic citizens, rather than the government. Similar to the indigenization decree of the late 1960s, this measure mostly targeted companies owned by resident Lebanese traders. Politically significant groups such as small shopkeepers and market traders supported these decrees. But the 1970s program went further and also legislated the partial indigenization of large, Western-owned businesses.Footnote 58 The main beneficiaries were relatively wealthy investors, as well as skilled employees and Ghanaian managers, who gained access both to lucrative investment and better positions in foreign companies. As this was mostly achieved through the sale of shares, foreign investors remained the main shareholders. Targeted nationalization, as in the case of gold mining, aimed to more strategically expand government control over the main sources of foreign exchange income.

The most consistent pressure, however, was applied to companies regarding their employment practices, suggesting a desire to open up more opportunities to better-educated members of the middle class, who left the country in large numbers in the 1970s to find a better life abroad, given the declining economy and the repressive political regime. Expatriate immigration quotas had been in place since the days of Nkrumah’s rule (1957–1966), but they became increasingly restrictive. Foreign firms were now at pains to show that they hired, trained, and promoted Ghanaians into responsible positions.Footnote 59 This suggests an attempt on the part of the military government to gain the support of a relatively broad section of the population: Predominantly urban, the alliance included groups such as uneducated owners of small shops; owners of medium-sized enterprises; well-educated, salaried, or professional middle classes; and relatively wealthy investors. Organized labor was noticeably absent here, even though it played a more significant part in the Latin American cases. In postcolonial Africa, trade unions had become dominated by political parties and only rarely found an independent voice or had the power to influence politics.Footnote 60

The Nigerian expropriations of the 1970s share some similarities with those of Ghana but in a context of greater political instability and booming oil prices. After the country became independent in 1960, it adopted a federal democratic system, plagued from the outset by regional rivalries and political tensions. The discovery of major oil and petroleum deposits in the Niger delta in the late 1960s influenced the political landscape of the independent country, and, in what came to be known as the “resource curse,” further undermined effective governance.Footnote 61 In 1966, Nigeria’s government was overthrown in a military coup, and ethnic tensions between the different regions led to the secession of eastern Nigeria under the name of Biafra. The ensuing civil war lasted from 1967 to 1970, and the control of the oil-producing areas in the Niger delta was key to the conflict. The willingness of international oil producers to collaborate with the Biafrans undermined their legitimacy in the eyes of the Nigerian government.

At the end of the Nigerian civil war, the government partly nationalized the three largest commercial banks, which were all foreign owned. This was a strategic decision to ensure access to finance for the subsequent indigenization decrees. In 1972, the first Nigerian Enterprise Promotion Decree (NEPD 1) favored domestic business owners similar to indigenization in Ghana, but targeted not just small to medium-sized companies but also larger international ones. The government negotiated separately with the oil companies over partial expropriations.Footnote 62 In 1975, Olusegun Obasanjo took over the military government, and his administration was critical of what NEPD 1 had achieved so far. NEPD 2 was announced in 1977 and aimed to be far more comprehensive than its predecessor. However, its implementation coincided with a slump in oil prices and general turmoil in the international economy, as several developing countries faced a debt crisis. In 1981 the Nigerian government reclassified several industries to attract foreign investment, effectively reversing many of the decisions of NEPD 2.Footnote 63 Falling oil prices curbed the political and economic gains that could be realized from expropriating existing foreign investment and increasingly limited the inflow of new international investment.Footnote 64 However, while prices fell from their peak in 1980, they never dropped below the already high level reached in 1973.

The NEPDs were shaped partly by the demands of Nigerian businesspeople, who effectively lobbied the government, especially for NEPD 1.Footnote 65 Local business owners stood to gain the most from expropriating Lebanese and Western small to medium-sized enterprises, and from being able to gain a stake in major Western multinationals.Footnote 66 Subsequently, public criticisms of NEPD 1 focused on redistributive issues, especially the highly oversubscribed public issues that led to the concentration of wealth in the hands of a few already affluent individuals and families, with around twenty individuals or family groups taking up the majority of the shares according to some estimates.Footnote 67 NEPD 2 showed greater control by the state bureaucracy but was too short-lived to achieve its aims fully.

These two cases evidence some of the conditions under which the domestic private sector of a country can choose to support the expropriation of foreign private property. In both cases, domestic businesspeople lobbied military governments in the name of economic decolonization and better domestic development.Footnote 68 Even though some sub-Saharan rulers gravitated toward the Soviet Union during the Cold War, this was not the case for Nigeria or Ghana after Nkrumah. Expropriations in these countries did not necessarily amount to hostility toward the private sector, they were, rather, a form of economic nationalism and were driven by domestic political concerns and volatile commodity prices, rather than ideological commitments. In countries where self-employment was more common than unionized employment, small domestic businesses sought government support against foreign competitors. The better-educated middle classes wanted improved employment opportunities and lobbied for reducing the number of expatriates holding senior posts. This created a political constituency in favor of expropriating foreign investors. However, these groups preferred indigenization over nationalization, which offered direct benefit in terms of investment and employment.

Government Alliance with State Bureaucracy

While indigenization was a common form of expropriation in West Africa, East African countries were more likely to opt for nationalization. We assume that the governments of host countries do not necessarily act as a homogenous entity, and consider instead how they are subjected to power struggles between different interest groups. In African countries, many of which were one-party states, intraparty competition was of particular relevance. In this section, we examine cases in which the expropriation of foreign property was a measure through which a government sought to maintain the support of party members or senior administrators. The history of expropriations in Tanzania and Zambia are instructive here, because both countries experimented with different types of “African socialism” and both had stable and long-term autocratic regimes.

Tanzania’s long-term ruler Julius Nyerere (1961–1985) provides a case in which a government undertook the most comprehensive attempt to convert “African socialism” into reality through a national scheme of village collectivization known as Ujamaa, which initially aimed to redistribute assets and services to small-scale collectives.Footnote 69 Nyerere announced the Arusha Declaration in 1967 because he had grown concerned at the power wielded by members of his party and the wider government bureaucracy. As party members were unsurprisingly not enthused by a program partly designed to curb their influence and control over resources, Nyerere sought to gain their support when he “announced a series of nationalizations that were guaranteed to garner public sympathy.”Footnote 70 These policies played well with a long-standing anti-foreign undercurrent within the party, as they most affected resident ethnic Asian and European businesspeople, similar to the targeting of Lebanese businesspeople in West Africa. Here, public enthusiasm was employed as a kind of “psychic gain” to camouflage other less popular measures, as argued by Albert Breton for the Canadian case.Footnote 71

The political alliance driving these policies was different from both the nationalizations in Latin America and the West African cases of expropriation. Neither labor nor domestic business was economically or politically strong enough to drive major changes in economic policies. Power was centralized in the one-party state, that is, Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) and the government administration. Civil servants had been prevented by colonial rules from joining TANU and were generally better educated, Western oriented, and focused on technocratic solutions to improve economic growth. TANU officials excelled through their political commitment to a left-leaning party, favored redistributive economic policies, and lacked the skills and expertise to exercise effective control of the civil service.Footnote 72 Support for nationalization came mainly from party officials, while civil servants were concerned about capital flight and a reduction in tax revenue.

Tanzania was heavily agricultural and lacked substantial industries, and opportunities for continued economic development were constrained without foreign capital, which dominated the economy. This was particularly obvious in finance and banking, as well as industrial production. When the nationalization of the banks and insurance was announced, most of those institutions’ finance was invested in London, out of reach of the Tanzanian government. After the Arusha Declaration, the state took over the banks, the National Insurance Corporation, and flour-milling firms, as well as controlling interests in seven industries, sisal production, and trading companies.Footnote 73 While the banks and other firms were in a relatively strong bargaining position, as they had relatively less capital in Tanzania at the time of nationalization, nationalizations remained popular with party leaders. They continued to press for more expropriations, and in 1970 Nyerere announced the nationalization of wholesale trade and private import–export firms, mostly controlled by Asians. This follows a familiar pattern, echoing West African indigenization programs targeting Lebanese to a significant extent. In 1976 Operation Maduka extended this to retail in Tanzania, seeking to replace small Asian-owned retail shops with co-operatives.Footnote 74

These policies were popular, because they opened up employment opportunities in the commercial sector and facilitated rapid promotion to management positions in the subsidiaries of international companies such as the banks.Footnote 75 The political importance of Africanization in Tanzania is shown by Nyerere’s 1964 attempt to abolish it on the grounds of racial discrimination. The army responded by an abortive military coup, which strengthened the hands of party officials who successfully pressed for the Arusha Declaration of 1967.Footnote 76 While socialist ideology in the form of “controlling the heights of the economy” and self-reliant national economic development became institutionalized from the late 1960s onward, Tanzanian nationalization reflected domestic political alliances not necessarily based on socialist ideology. Party officials sought the support of the electorate by opening up employment opportunities through nationalization, whereas civil servants’ interests were, in general, aligned with foreign investors, as they sought the capital for development initiatives.

By the late 1970s, economic crisis engulfed Tanzania: Between 1978 and 1985, manufacturing declined from 13.5 to 6.9 percent of the GDP, which also shrank in that period. While the country maintained democratic elections throughout that time, the elected parliament was fairly powerless, as a small alliance of bureaucrats and party members retained significant influence.Footnote 77 Although Nyerere’s approach to nationalization was populist and aimed at gaining the support of a larger alliance within his party and beyond, it ultimately mostly benefited a narrow alliance of mainly party members and some civil servants who directly controlled the assets of foreign firms.Footnote 78

The Zambian expropriations highlight a similar strategy of seeking to ensure the continued support of different groups of government officials during the tenure of Kenneth Kaunda, who led the United National Independence Party (1964–1991). The nationalizations of the copper mining companies in Zambia received a significant amount of attention in the general media and scholarly literature (similarly to the nationalization of copper mining in Chile).Footnote 79 Zambia’s economy and government were highly dependent on the performance of this notoriously cyclical industry.Footnote 80 Although other privately owned companies operated in Zambia, many were either resident expatriate–owned or foreign-owned and were significantly smaller than the copper companies. Zambian-owned enterprises were limited, as they had been restricted from trading during the colonial period. The National Wholesale and Marketing Company was in part a vehicle to support the expansion of private Zambian business, but progress was perceived as too slow.Footnote 81 As part of the government’s decision to “localize” the economy, in 1968 and 1969 Kaunda requested partial nationalization of foreign firms in return for adequate compensation. At the same time, several parastatal organizations (state-owned enterprises) were created to oversee the performance of the public–private joint ventures, in line with ideas of African socialism. These parastatals wielded significant political influence, led by Zambians such as Andrew Sardanis at the Industrial Development Corporation of Zambia Ltd. (INDECO). Even though they were not technically part of the administration, they were effectively controlled by the government.Footnote 82 Parastatals were staffed by well-educated, younger professionals, often referred to as “technocrats,” for whom there were no obvious openings in the civil service and the party ranks, and who were paid higher salaries in the parastatals than could be achieved in the regular civil service.Footnote 83

With a surprise announcement in 1973, the Zambian government fully nationalized the two copper mining joint ventures ahead of significant increases in copper prices. But even more significantly for their domestic alliances, they placed the supervision of mining under two ministries, thus reassigning a function that was previously performed by a parastatal. Civil servants asserted control over nationalized companies, at the expense of the technocrats leading parastatals. While organized labor was a significant constituency in the Copperbelt, the union remained relatively unpolitical, and strikes were banned by the Zambian government in this period. More significant were divergent interests within the state that crystallized around three groups: politicians, civil servants, and technocrats. Similar to Tanzania, the politicians were less well educated than the civil servants and the technocrats, while the civil servants were established in top ministerial posts. As the pace of promotion slowed down with the near completion of the Africanization process from which the civil servants had benefited, the relatively younger group of technocrats had fewer opportunities.Footnote 84 Nationalization opened up well-paid positions in the parastatals for technocrats and some entrepreneurs, which created conflict with less well-paid civil servants. Earlier nationalizations also increased the influence of technocrats like Sardanis, leading to conflict with politicians and civil servants. The technocrats had dominated the earlier partial nationalization, while the later expropriations were prompted by further internal political divisions within the government.Footnote 85 Similar to the nationalizations in Tanzania, the Zambian nationalizations were driven by quite a narrow constituency within the public sector that, despite its limited scope, experienced internal competition between different groups of party members and civil servants, most notably the younger generation of technocrats and the civil servants in charge of ministries.

A New Framework for Understanding Expropriation

Business historians have studied economic nationalism, expropriations, and their impact on companies extensively.Footnote 86 However, many other disciplines have been more influential in putting forward general explanations of why countries would seek to expropriate, which we review in the next section.Footnote 87 This is partly because the research questions that business historians have asked differ significantly from those in international business or political economy. Historians have been more interested in why some governments expropriate while others do not under similar circumstances, how they choose to implement expropriation, and who ultimately benefits from expropriations. It is nevertheless more difficult to generalize from a diverse set of individual in-depth case studies that span different continents and periods, and this has limited the influence of historical research on the wider debate. This is why we believe that a more historiographical approach that synthesizes existing historical research has the potential to offer new insights to historical as well as interdisciplinary researchers.

Historiography summarizes historical controversies that often focus on similar research questions or the same historical event, period, or topic. This is not the case for historical research on expropriations, which often asks different research questions while focusing on different countries and periods. Hence, we engaged with debates on comparative historiography, but focus on how narrative synthesis can be useful to business history in generating frameworks to understand and compare in-depth historical cases. The necessity of drawing upon the existing historical research more synthetically was already recognized in the 1950s and gained greater traction in the 1980s as comparative history.Footnote 88 More recently, the notion of comparative historiography has come to the fore again, but mostly as comparative work on the nature of historical writing in different cultures, rather than the more empirical approach that we develop here.Footnote 89

In our synthesis, we first focus on the role of economic nationalism in establishing the historical legitimacy of the nation-state. Historians maintain that the legitimacy of a nation-state is built on a series of widely accepted myths around the country’s creation and general characteristics, often promoted from above through “conscious and deliberate ideological engineering.”Footnote 90 National movements often gained independence from their former colonial metropoles without military conflict when they formed “newly emancipated states claiming a national identity which they did not possess.”Footnote 91 Defining a national identity within new territorial borders inhabited by diverse cultural and ethnic groups posed distinct challenges. Elites in “peripheral countries” (meaning those not belonging to Western Europe, the United States, and other areas of the wealthy world) face the problem of trying to generate national pride in countries that are poor and subordinated to the world powers.

One way in which those elites dealt with this challenge consisted of promoting unity and a sense of belonging to a nation-state by romanticizing the country’s peripheral status and promoting a sentiment of pride around the perceived necessity of “resistance” against exploitative imperialism.Footnote 92 Persistent poverty means that peripheral elites struggled to generate national pride around nonmaterial issues. Therefore, developing countries whose economies were dominated by the export of one or two natural resources created a sense of national belonging around narratives in which those exports represented the promise of future economic development and stability.Footnote 93 Countries with these characteristics often developed nationalism around a sense of collective ownership of a natural resource or other economic activities considered a feature of national identity.Footnote 94

The population of a peripheral country can make common cause around the defense of domestic control or ownership of export products or main economic activity. For instance, from the 1960s to the 2000s, different Latin American governments used the same slogan when expropriating foreign oil: “The oil is ours.”Footnote 95 In a discussion of Canadian economic nationalism, Breton argued that this populist rhetoric resulted in an intangible “psychic gain.”Footnote 96 Our analysis of the expropriation of foreign property engages with these theoretical approaches to peripheral economies by taking into consideration both the challenges of building a nation-state in the twentieth century as well as the mobilization of the population around the fate of an export product or key economic sector under foreign control.

Thus the longevity of the nation-state is a crucial element to understand expropriations of foreign private property. Nation-states had already consolidated when major expropriations took place in Latin America, whereas in sub-Saharan Africa, they had not. Latin American nation-states emerged between the 1820s and the 1870s. During this period, most Latin American countries went from being part of the Spanish Empire to having their national borders defined in a way that does not differ much from those we find in the early twenty-first century. This means that by the early twentieth century, most Latin American states had developed some administrative capacity and no longer faced contestations regarding who belonged to the national community and had citizen’s rights. By the early twentieth century, few Latin Americans challenged the idea that their national identities included European elements such as the Spanish and Portuguese languages or the Catholic faith. Most post-1920s social conflicts in Latin America were defined by class struggles rather than by national identity, with the labor movement playing an increasingly important role in the evolution of political parties.Footnote 97

In sub-Saharan Africa, expropriations took place after the 1960s, when those countries were experiencing a process of postcolonial state formation with the attendant need to legitimize these new political units. During this period, these countries were still defining what it meant to be a national citizen and, in determining this status, granted increased importance to ethnic origin over the place of birth or residence.Footnote 98 Most African states emerged out of colonial administrative units that reflected international diplomacy and a pattern of exploration and subjugation that bore little similarity with preexisting political, ethnic, or social divisions.Footnote 99 There were few cases of territorial states in Africa before colonial expansion in the nineteenth century. Thus, the colonial languages were frequently the only languages spoken jointly, although in East Africa Kiswahili was significant, and elsewhere European languages were localized as Krio/Creole and Pidgin. The majority of former British, Belgian, and French colonies gained independence in the 1960s, for the most part in a relatively orderly process of constitutional devolution.Footnote 100 African nationalists were frequently co-opted by colonial administrations during decolonization (with some important exceptions).Footnote 101

The features of expropriation policies in sub-Saharan Africa should be viewed in this context (for a summary, see Table 2). Expropriation policies did not just reflect attempts on the part of governments to create political alliances; they also aimed to enhance the fundamental institutional legitimacy of the state itself.Footnote 102 The state needed to provide opportunities and income to its most important constituencies, especially the urban and educated population.

Table 2 Winning alliances and policies toward foreign investors as strategies for political survival.

Note: Compiled by the authors.

A second significant element defining the composition of the alliances is the strength of labor unions. By the 1920s and 1930s, labor unions in many Latin American countries played an important political role and employed nationalist rhetoric. Conversely, labor unions did not play a significant role in most sub-Saharan African countries after independence. Unions and independent African governments had an often complicated relationship (in some cases, like in Zambia, this was because white workers dominated the unions).Footnote 103 In other cases, young professionals working for foreign firms did not always see unions as the best means of advancing within these firms, especially as the unions were either fractured or controlled by the ruling party and thus deeply politicized.Footnote 104

A final factor is the presence of a sizable number of domestic businesspeople with effective political representation. In the West African cases, the political influence of small urban market traders was comparable to that of the labor unions in Latin America, but of a different nature. Moreover, politically influential elite families also sought to protect or extend their business interests. For the East African cases, these groups were relatively weak and politically marginalized. In most Latin American countries, domestic business owners were closely associated with the government, but during periods of populist rule, they were on the defensive.Footnote 105 As we show later, however, they could on occasion be part of a political alliance against foreign capital if they perceived that economic benefits could ensue from that action.

We explain how governments in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa sought the support of different groups of political supporters by drawing on selectorate theory, which focuses on the mechanisms of political survival.Footnote 106 This theory assumes that all types of governments (whether they are elected officials or dictators) will need to respond to a specific constituency.Footnote 107 Even the most openly dictatorial regimes are aware of the need to secure the loyalty of a mass of people to whom they offer economic benefits and not simply out of fear.Footnote 108 Similarly, elected officials seeking to secure their re-election or that of their political party may engage in the political game to ensure the loyalty of this alliance that will mobilize voters to the polls. Thus, the selectorate theory school maintains that the main goal of economic policy (in either authoritarian regimes or pluralistic ones) is to ensure the political survival of those in power (either an individual, a military junta, or a political party). This means that, when necessary, a country’s rulers will follow economic policies that ensure the loyalty of their alliance even if those policies go against their official ideology or do not translate into more growth or efficiency.Footnote 109 We refer to this as “political alliance.” If the rulers’ survival depends on a relatively small political alliance (say a few generals, some families, or a particular ethnic group), they will develop economic policies that particularly benefit the members of that group. Conversely, if government’s survival depends on a large-scale political alliance (e.g., voters of a particular party, large labor unions, a large revolutionary army, or even a large ethnic group), economic policy would seek to distribute economic rents among that large number of members that make up this political alliance.Footnote 110

From our comparative case histories, we conclude that the interplay between these two factors—nationalism and political alliances—determined decisions to expropriate, often in conjunction with the movement of international prices for commodities controlled by expropriated firms. When general conditions were favorable for expropriation, it became attractive for governments in developing countries to gain political support through economic nationalism. While many countries expropriated foreign investors in the middle of the twentieth century, not all developing countries did so. Economic nationalism became an important factor if the longevity and legitimacy of the nation-state were key political issues that would mobilize political support. For West Africa, Paul Collins and Thomas Biersteker, for example, highlighted that domestic redistribution struggles drove expropriations.Footnote 111 Ernest Wilson argued that country studies alone did not reflect how nationalization and indigenization in Africa were driven by the relative economic and political influence of the domestic business (broadly seen as favoring indigenization) and bureaucrats (favoring nationalization).Footnote 112

By generalizing at this level, we do not want to downplay either the diversity of these two continents or the complexity of their political and economic histories. We believe that studies investigating the types of political alliances could be extended to other countries and periods. By focusing the explanation on central analytical issues such as the longevity of the nation-state and the political influence of specific domestic constituencies, we construct a broad explanatory framework that allows business historians to compare different cases of expropriation across time and space.

Conclusion

This paper proposes a model of alliances that support the expropriation of foreign private property in developing countries. We demonstrate how different types of expropriations correspond to strategies for political survival in which rulers need to ensure the support of their constituencies. We categorize these alliances according to which stakeholders were mobilized around the government expropriation policies and who had a significant influence on the ultimate design of expropriation decrees or expected rewards from the expropriation: labor unions, domestic businesses, or public servants. Our categorization takes into account the legitimacy and longevity of the nation-state and the political importance of organized labor or domestic business. Our research complements other studies that have focused on technological and host country institutional characteristics of the industry and the impact of the evolution of international commodity prices. We extend and integrate these insights by considering the cases of sub-Sahara African and Latin America, which highlight the dynamics between labor, party politics, and domestic business. This needs to be understood in terms of how economically developed these countries are, and how clearly defined and secure the concept of national identity and the nation-state is. We are aware that the type of alliances defined in this paper are not the only possible ones, but we hope this paper will open the door for other scholars to define other types of coalitions governments build around expropriation policies.