Introduction

Alienation towards parents often occurs when couples divorce (Darnall, Reference Darnall2011; von Boch-Galhau, Reference von Boch-Galhau2018), and one parent indoctrinates the child to dislike, fear, and avoid contact with the other parent. Such alienation has been listed in DSM-5 (Bensussan, Reference Bensussan2017), the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), under diagnostic code V 995.51, ‘child psychological abuse’. Alienation towards parents can also occur naturally outside the parental divorce context, e.g. if the child was left behind when one or both parents left home to work. In China, more than 61 million children have been left behind when one or both of their parents left home for more than 6 months (Ministry of Civil Affairs, 2010). In a previous study, we designed an Inventory of Alienation towards Parents (IAP) and used it to investigate and confirm the high levels of alienation towards parents in Chinese left-behind children (Dai et al., Reference Dai, Yang, Hu, Wang, Liu, Guang, Zhang, Xu, Liu, Yang and Feng2017), which revealed that parents’ departure and absence in children's daily life quantitatively damaged the affection of children towards their parents. Despite this, research on alienation status in left-behind children is still lack, especially regarding the potential impact of alienation towards parents on children's health and ways of coping with the problem (Migchels and De Wachter, Reference Migchels and De Wachter2017).

The possible influence of parent alienation has been discussed based on general empirical experience (von Boch-Galhau, Reference von Boch-Galhau2018); however, such exploration has not previously been supported by reliable evidence from quantitative investigation. Among the variety of potential consequences of alienation towards parents, the most important outcome should be children's mental health (Verrocchio et al., Reference Verrocchio, Marchetti, Carrozzino, Compare and Fulcheri2019). Specifically, exposure to parent alienation behaviour was associated with three mental health outcomes: depression, state anxiety, and trait anxiety, indicating an increased risk for subsequent poor mental health (Verrocchio et al., Reference Verrocchio, Baker and Bernet2016). A retrospective study found that childhood exposure to alienation towards parents was related to a higher likelihood of depressive symptoms and diminished quality of life in adulthood (Verrocchio et al., Reference Verrocchio, Marchetti, Carrozzino, Compare and Fulcheri2019). Such an influence has also been confirmed in adolescents: adolescents with a strong sense of alienation towards their parents were more susceptible to depressive symptoms (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Hou and Gonzalez2017). These results confirmed the effect of alienation towards parents on children's depression through cross-sectional investigations of alienation in children during parental divorce. However, the causal relationship of alienation towards parents and depression in left-behind children remained unexplored, which necessitated longitudinal follow-up investigation.

Importantly, the effect of alienation on depression may be mediated by other factors. There is extensive evidence that contextual negative life events are related to occurrence of depression (Kendler et al., Reference Kendler, Karkowski and Prescott1999; Bifulco et al., Reference Bifulco, Bernazzani, Moran and Ball2000), which might be a possible risk mediator between alienation and depression. In our previous investigation, left-behind children who had experienced negative life events had stronger alienation towards parents (Dai et al., Reference Dai, Yang, Hu, Wang, Liu, Guang, Zhang, Xu, Liu, Yang and Feng2017), which further suggested a potential mediation of life events. In addition to life events, resilience has been frequently reported to be involved in the psychopathology of depression (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Westphal and Mancini2011; Lee and Seo, Reference Lee and Seo2018); this might be a possible protective mediator between alienation and depression. Parent−child alienation mediated the relations between parental warmth and hostility and adolescent resilience in one study (O'Gara et al., Reference O'Gara, Calzada and Kim2020), which connected alienation with resilience. Direct investigation confirmed that adolescents with a stronger sense of alienation towards parents or low resilience experienced more burden or less efficacy in translating and were more susceptible to depressive symptoms (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Hou and Gonzalez2017). These results suggested a potential interaction between negative life events and resilience; however, these effects were not tested directly, and none of these studies used longitudinal data. Thus, the predictive pathway from alienation to depression remains unelucidated.

As discussed previously, parents’ divorce can increase alienation towards parents (Darnall, Reference Darnall2011; von Boch-Galhau, Reference von Boch-Galhau2018); thus, parents’ marital status may potentially influence the incidence of depression in children. Moreover, our previous investigation showed that left-behind variables such as age at the time of parents’ departure and duration of parents’ absence significantly influenced alienation towards parents (Dai et al., Reference Dai, Yang, Hu, Wang, Liu, Guang, Zhang, Xu, Liu, Yang and Feng2017), which might influence the effect of alienation on depression as a moderator. Again, potential interactions of these factors with alienation towards parents and depression have not been tested currently, and their role in the development of depression in left-behind children is largely unknown. Better understanding of these factors can facilitate identification of the population at risk for depression in children.

In sum, the current study aimed to observe the prediction of alienation towards parents on children's depression with a 12-month longitudinal investigation in a sample of left-behind children, as well as mediation by negative life events and resilience and moderation by left-behind variables and parents’ marital status. Our hypotheses were as follows: (1) Alienation towards parents may predict depression 12 months later in left-behind children. (2) Negative life events and resilience may mediate the effect between alienation towards parents and children's depression. (3) Left-behind variables and parents’ marital status may moderate the effect between alienation towards parents and children's depression.

Methods

Participants

Children were eligible for this study if they were third to sixth grade primary school students in rural China and could read and write Chinese. Originally, 1620 students from primary school (aged between 8 and 15 years old) in the Chongqing area of China were enrolled. Among them, 1388 students completed the questionnaire at baseline (87.61% were left-behind children), and 1090 completed the questionnaire at the 12-month follow-up (85.5% were left-behind children, male/female: 568/522, age: 10.58 ± 1.03).

Instruments

Socio-demographic information was collected with a demographic questionnaire specifically designed for this study, which included gender, age, parents’ marital status (undivorced, divorced, father remarried, mother remarried, both remarried), and left-behind variables [parents absent or not, lodging at school or not, type of caregiver at home (parents, grandparents, siblings, relatives, neighbours, none), duration of parents’ absence (no absence, 6 months to 2 years, 3–5 years, ⩾6 years].

The Chinese version of the Inventory of Alienation towards Parents (IAP) was included to investigate alienation towards mothers and fathers. The IAP was developed in our previous research and is comprised of paternal and maternal forms with Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.887 and 0.821, respectively (Dai et al., Reference Dai, Yang, Hu, Wang, Liu, Guang, Zhang, Xu, Liu, Yang and Feng2017). Higher scores indicate higher alienation towards parents.

The Chinese version of the Children Depression Inventory (CDI), which was revised by Kovacs (Reference Kovacs1985), was used to evaluate children's depression levels. This scale comprises 27 items and is applicable to children aged 7−17 years old (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhang, Hu, Chen, Zhang, Yu, Li and Wei2009), with good validity (Cronbach's alpha coefficient 0.82) and reliability (Samm et al., Reference Samm, Värnik, Tooding, Sisask, Kölves and von Knorring2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Lu, Tan and Yao2010). A score of 19 was recommended as the cut-off point for the screening of depression (Kovacs, Reference Kovacs1985).

The Adolescent Self-Rating Life-events Checklist (ASLEC) (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Liu, Yang, Cai, Wang, Sun, Zhao and Ma1997; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Ma1999), which was developed by Liu in 1997, was adopted to assess the stress level of subjects. This scale assesses the severity and frequency of stress during the past 6 months, which is comprised of 27 items and has five-point scoring: 5, ‘severe influence’; to 1, ‘no influence’. This scale has good validity and reliability, with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.85.

The Adolescent Resilience Scale (Hu and Gan, Reference Hu and Gan2008), which was developed by Hu and Gan, was used to evaluate the resilience level of children. This scale has 27 items in total, with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.839. Higher scores indicate higher resilience.

Procedure

Children who were willing to take part signed written informed consent of the study, which was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee, Army Medical University. The researchers explained the study to the children in class. After this, children applied for participation independently. Self-report questionnaires were investigated in the classrooms of primary school at two time points [baseline (T1) and 12-month follow-up (T2)]: IAP, CDI, ASLEC, and the Adolescent Resilience Scale. Children were debriefed and received incentives after the follow-up survey.

Statistics

To address our hypotheses, Pearson's correlation analyses were computed to examine the correlations among demographic variables, alienation towards parents, negative life events, resilience, and depression. Multiple stepwise regression analysis (Method: enter) was conducted to examine the impact of demographic variables, alienation towards parents, negative life events, and resilience on depression. A structural equation model was carried out with AMOS 24.0 to test the direct, mediating and moderating effects of alienation on depression (Baron and Kenny, Reference Baron and Kenny1986). Bootstrap tests (2000 repeated samples and 95% confidence intervals) were used to test the significance of the mediating effect, with a 95% CI that did not contain 0 indicating a significant mediating effect.

Results

Descriptive data

In children, the alienation scores towards parents were approximately 16 (Table 1). Alienation towards mothers (16.42 ± 7.27 and 15.69 ± 6.96) was relatively higher than alienation towards fathers (15.63 ± 7.17 and 15.06 ± 6.85) at baseline (T1) and at the 12-month follow-up (T2): F (1, 1088) = 13.718, 11.012, p < 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.022. Setting ⩾19 as the cut-off score (Kovacs, Reference Kovacs1985), 21.01% of children (n = 229) reported a status of depression.

Table 1. Correlation analyses between variables

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Correlation analyses between variables

Table 1 shows correlation of variables: children's age, parents’ marital status, absence of one or both parents, inadequate caregiver at home, and duration of parents’ absence were positively correlated with depression (r = 0.06–0.16, p < 0.05); negative life events and alienation towards parents were negatively correlated with resilience (r = −0.08, p < 0.01). Moreover, depression, negative life events, and alienation towards parents were positively correlated with each other (r = 0.19–0.59, p < 0.01) and negatively correlated with resilience (r = −0.24 to −0.59, p < 0.01).

Regression analysis for children's depression

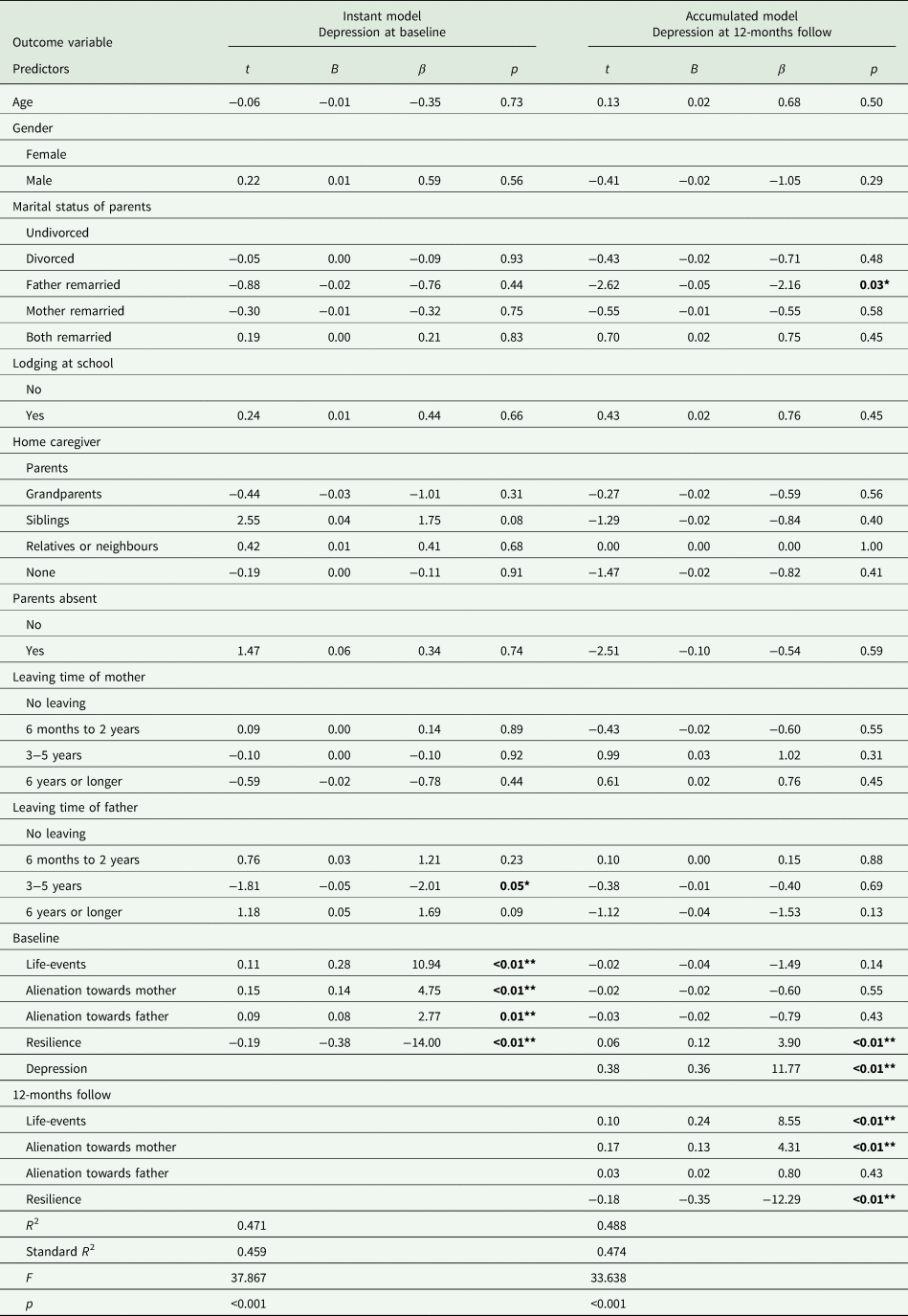

To observe the instant predictors of depression, with children's depression at baseline as the dependent variable, and demographic and left-behind variables, baseline alienation towards mother and father, negative life events, and resilience as independent variables, regression analysis was conducted (Table 2). The analysis showed that negative life events and alienation towards parents positively predicted depression, while fathers leaving for 3–5 years and resilience were negative predictors of depression, F = 37.867, standard R 2 = 0.459, p < 0.001.

Table 2. Regression analysis of variables

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

To observe the delayed predictors of later depression, with children's depression of 12-months follow-up as the dependant variable, and demographic and left-behind variables – baseline (T1) and 12-months follow-up (T2) alienation towards mother and father, negative life events, and resilience – as independent variables, regression analysis showed that T1 depression and resilience, T2 negative life-events and alienation towards mothers positively predicted depression at 12-months follow-up, while fathers’ remarriage and T2 resilience were negative predictors of depression, F = 33.638, standard R 2 = 0.474, p < 0.001.

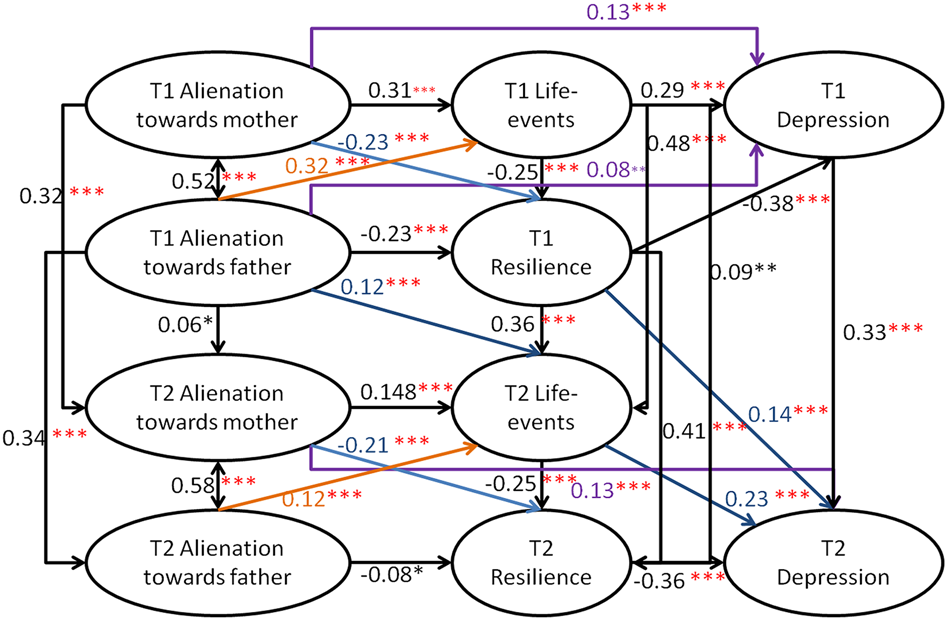

AMOS structural equation model test for children's depression: mediation effect

Based on the regression results, a hypothesis-driven structural equation model test was carried out, which showed a saturated model for the instant model; alienation towards mothers (direct effect = 0.128, p < 0.001; indirect effect = 0.208, p = 0.012) and fathers (direct effect = 0.076, p < 0.01; indirect effect = 0.145, p = 0.019) predicted depression in children directly and indirectly; the corresponding 95% CI did not include 0, indicating significant mediating effects (Figs 1 and 2, online Supplementary Table S1). Negative life events were the strongest positive predictor of children's depression (direct effect = 0.285, p < 0.001; indirect effect = 0.095, p = 0.008), while resilience was the strongest negative predictor of children's depression (direct effect = −0.382, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1) (indirect effect see online Supplementary Table S1).

Fig. 1. AMOS structural equation model test for children's depression: Instant model.

Fig. 2. AMOS structural equation model test for children's depression: Accumulated model.

The accumulated model showed good model fit, CMIN/DF = 2.796, NFI = 0.988, IFI = 0.992, CFI = 0.992, RMSEA = 0.041. T2 alienation towards mothers (direct effect = 0.13, p < 0.001; indirect effect = 0.121, p = 0.007) predicted T2 depression directly and indirectly, while T2 alienation towards fathers (indirect effect = 0.066, p = 0.006) and T1 alienation towards mothers (indirect effect = 0.234, p = 0.013) and fathers (indirect effect = 0.133, p = 0.009) predicted T2 depression indirectly. T1 negative life events (indirect effect = 0.25, p = 0.009) predicted T2 depression indirectly, while T1 resilience (direct effect = 0.14, p < 0.001; indirect effect = −0.275, p = 0.01) and T2 negative life events (direct effect = 0.23, p < 0.001; indirect effect = 0.089, p = 0.002) predicted T2 depression directly and indirectly. T2 resilience was the strongest negative predictor of T2 depression (direct effect = −0.36, p < 0.001), while T1 depression was the strongest positive predictor of T2 depression (direct effect = 0.33, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

AMOA model test for children's depression: moderation effect

Based on the regression results, duration of fathers’ absence was also included in the model test as a moderator, which showed that duration of fathers’ absence moderated the instant model significantly, p = 0.011, CMIN/DF = 1.581, NFI = 0.963, IFI = 0.968, CFI = 0.986, RMSEA = 0.023. Online Supplementary Table S2 shows that when fathers were absent for 3−5 years, the correlation between alienation towards mothers and fathers was highest (p < 0.001).

Based on the regression results, parents’ marital status was also included in the model test as a moderator, which showed that parents’ marital status moderated the accumulated model significantly, p = 0.008, CMIN/DF = 1.615, NFI = 0.962, IFI = 0.985, CFI = 0.985, RMSEA = 0.024. Online Supplementary Table S2 shows that when the father or both parents remarried, alienation towards fathers led to more depression (p < 0.001). When the father remarried, negative life events of children led to more depression (p < 0.05), while when mothers remarried, alienation towards mothers resulted in lower resilience (p < 0.05).

Discussions

The current investigation is among the first to longitudinally observe the prediction of alienation towards parents on depression 12 months later in left-behind children. The findings confirmed that alienation towards parents predicted depression 12 months later in the left-behind sample, and that negative life events and resilience were mediating factors and that duration of fathers’ absence and parents’ marital status were moderating factors.

Alienation scores towards parents were approximately 16, which was similar to our previous report (16.71 for alienation towards mothers, 16.34 for alienation towards fathers) (Dai et al., Reference Dai, Yang, Hu, Wang, Liu, Guang, Zhang, Xu, Liu, Yang and Feng2017), indicating relatively high levels of alienation towards parents in left-behind children. Moreover, alienation towards mothers was relatively higher than alienation towards fathers, which was also consistent with our previous investigation (Dai et al., Reference Dai, Yang, Hu, Wang, Liu, Guang, Zhang, Xu, Liu, Yang and Feng2017). Furthermore, we found that 21.01% of left-behind children reported a status of depression, which was close to our previous findings in western China (23.9%) (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Feng, Yang, Yang, Dai, Hu, Liu, Guang, Zhang, Xia and Zhao2015).

Correlation analysis showed that demographic factors, including age of children, parents’ marital status, absence of parents, inadequate caregiver at home, and duration of parents’ absence were positively correlated with depression, negative life events, and alienation towards parents, which were positively correlated with each other and negatively correlated with resilience. The results confirmed that demographic factors and psychological variables at baseline and at the 12-month follow-up were correlated with each other. Thus, we carried out regression analysis and model tests to further explore their causal relationship.

Linear regression indicated that in the instant model, alienation towards parents, negative life events, resilience, and fathers leaving for 3–5 years predicted depression of children significantly. The accumulated model confirmed the instant model and further confirmed the prediction of previous resilience and depression, and the father's remarriage on later depression. Based on regression results, the AMOS model test showed that in the instant model, alienation towards parents predicted depression of children directly and indirectly through negative life events and resilience. In the accumulated model, only T2 alienation towards mothers predicted T2 depression directly, while T2 alienation towards fathers and T1 alienation towards both parents predicted T2 depression indirectly through T1 depression, negative life events, T2 negative life events, and resilience. The results suggested that alienation towards parents was a predictor of depression 12 months later in children, which was partially mediated by negative life events and resilience. The findings were consistent with ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner1979), which posits that personal, family, and social factors have a synergistic effect on children's development and mental health. Our findings highlighted the role of family variables, especially alienation towards parents, and endogenous resilience and exogenous life events in the development of depression in left-behind children, which can help to identify the population at risk of depression among children. This is first report of its kind, as far as we know.

Alienation towards parents at T1 and alienation towards fathers at T2 predicted T2 depression indirectly, and only T2 alienation towards mothers predicted T2 depression directly. Moreover, alienation towards mothers was a stronger predictor of children's depression than alienation towards fathers. The results confirmed a stronger and more profound predictive effect of alienation towards mothers on children's depression, which was consistent with previous findings that mothers have a stronger influence on their offspring's lifetime mental health (Malmberg and Flouri, Reference Malmberg and Flouri2011). Compared with previous results mainly from research on children's attachment towards parents (Zeanah et al., Reference Zeanah, Keyes and Settles2003; Stansfeld et al., Reference Stansfeld, Head, Bartley and Fonagy2008), the current finding confirmed the knowledge from the perspective of alienation towards parents for the first time.

Negative life events positively predicted current depression directly and later depression indirectly. As a well-reported vulnerability to depression (Kendler et al., Reference Kendler, Karkowski and Prescott1999; Bifulco et al., Reference Bifulco, Bernazzani, Moran and Ball2000), the current study confirmed the role of negative life-events in the mediation between alienation towards parents and depression. Resilience, in contrast, predicted current and later depression directly and indirectly, and was also the strongest negative predictor for current depression. The results suggested an important meditative effect of resilience between alienation towards parents and depression. Previous depression had the strongest positive prediction on later depression, which was consistent with previous reports (Gan et al., Reference Gan, Xie, Duan, Deng and Yu2015). Together, the results confirmed the significant indirect prediction of alienation towards parents on later depression of children through negative life events, depression, and resilience. This knowledge help to prevent, and potentially even cure children's depression when high levels of alienation towards parents are present.

Moreover, although the regression model showed that fathers leaving for 3−5 years and fathers remarriage were negative predictors of depression, in the moderation models, both brought some risks. However, online Supplementary Table S2 shows that all pathway coefficients of fathers leaving for 3−5 years and fathers remarrying were larger, which indicated that children's depression was more sensitive to the effects of alienation, negative life events, and resilience compared with other durations of fathers’ absence and other parents’ marital statuses. Therefore, the negative effect of fathers leaving for 3−5 years and fathers remarrying on children's depression seemed to be a result of moderation compensation. The results suggested that in the prevention of depression in children, families and schools should pay attention to the duration of parents’ absence and parents’ marital status.

Limitations: Some important factors, such as social support, were not assessed in this study, which may limit the explanatory power of the findings.

In summary, the current investigation is among the first to longitudinally observe the prediction of alienation towards parents on children's depression. The results confirm that alienation towards parents is a predictor of children's depression 12 months later, as well as the mediation effect of negative life events and resilience and the moderation effect of duration of father's absence and parents’ marital status. The findings provide important suggestions for families and schools; i.e. to prevent depression in children, parent−child bonds, especially alienation towards mothers, should be carefully considered, and individuals with more negative life events and weaker resilience may need further attention.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000329

Data

Data which is analysed in this study is available upon request.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Yang of the Third Military Medical University for her support for undergraduate recruitment. We appreciate the hardwork of all graduate students who took part in this study as research assistants.

Financial support

Doctor Dai claimed that this work was supported by the key project of Nature Science Foundation of Chongqing (cstc2020jcyj-zdxmX0009), National Social Science Fund of China (17XSH001), the Key project and innovation project of People's Liberation Army of China (18CXZ005, BLJ19J009).

Conflict of interest

All authors have known the potential conflicts of interest, and have the declarations of no conflicts of interest in the future. All authors stated that the content has not been published or submitted for publication elsewhere.