The philosophical and legal tradition known collectively as “just war theory” is conventionally divided into two main sets of guiding principles. The principles of jus ad bellum address the decisions of governments to initiate war, while the principles of jus in bello regulate the conduct of soldiers in combat once fighting has commenced. One of the fundamental precepts of prevailing (often called classical or traditional) interpretations of just war doctrine is that these sets of ethical principles should remain independent of each other. Traditional just war doctrine delineates a division of moral responsibility in which political leaders are responsible for the initiation of a war, while soldiers are responsible only for their own conduct during the war. Leaders who initiate an unjust war are not morally exculpated if their armies follow the principles of jus in bello, but individual soldiers who fight for an unjust cause are not morally tainted by the war's immoral foundations. Similarly, individual soldiers who fight for a just cause are not excused by the war's moral foundations if they fight in an unethical manner. According to traditional interpretations of just war doctrine, soldiers fighting in an unjust war of aggression and soldiers defending their nation from such an attack are morally equal as long as they obey the rules of jus in bello.Footnote 1

Although the principle of moral equality has always been contentious, over the last fifteen years the principle has come under increased scrutiny by a group of scholars often referred to collectively as just war theory revisionists.Footnote 2 These scholars have challenged many aspects of traditional interpretations of just war doctrine, but the concept of the moral equality of soldiers has been the focus of the most intense revisionist critique.Footnote 3 According to revisionist scholars, soldiers who fight for an unjust cause bear some responsibility for their part in advancing the unjust war, even if they conduct themselves according to jus in bello rules. To suggest otherwise, they argue, would contradict widely accepted notions about the morality of self-defense and the immorality of aggression in contexts outside of war.

Traditional and revisionist scholars appear to agree, however, that the public accepts the traditionalists' division of moral responsibility. What they disagree about is whether the public's belief in the moral equivalence of soldiers is a good or bad thing. Michael Walzer, the prominent political theorist who defends a traditional view, writes that “by and large we don't blame a soldier, even a general, who fights for his own government.”Footnote 4 Walzer finds this public acceptance reassuring, stating that “ordinary moral judgement” endorses the view that “the atrocities [a soldier] commits are his own; the war is not. … [The war is] the king's business.”Footnote 5 In contrast, Jeff McMahan, a prominent revisionist philosopher, finds this belief to be both ubiquitous and disturbing, and poses the following questions:

Why do we so readily accept that rank-and-file Nazi soldiers who killed other soldiers from all over Europe as a means of conquering their countries were merely doing their duty as soldiers, provided they refrained from deliberately attacking civilians? More generally still, why have most people in virtually all cultures at all times believed that a person does not act wrongly by fighting in an unjust war, provided that he obeys the principles governing the conduct of war?Footnote 6

In fact, public attitudes about the moral equality of soldiers remain largely unstudied. While political scientists have recently used survey experiments to study public opinion on the ethics of the use of torture, drones, and nuclear weapons, this article is the first systematic examination of how the American public thinks about the relationship between the ethics of soldiers’ actions and the justice of the war in which they are fighting.Footnote 7

The implications of whether or not the public accepts the moral equality principle extend well beyond the pages of academic journals. Just war theory remains an influential source of guidance for thinking about the morality of war, and its principles are cited frequently by policymakers seeking to defend or denounce the initiation of a particular conflict or to justify specific combat operations once war is underway. Most directly, public opinion about the principle of moral equality can influence the ethical judgments citizens render on real wars, on the soldiers who fight them, and on the leaders who initiate them.

Soldiers, not just political leaders and voters, can also be influenced by just war theory and their understanding of the moral equality of combatants. The history of warfare is replete with examples of soldiers who refused to participate in war—even in the lawful killing of other combatants—when they perceived the war's cause to be unjust.Footnote 8 Revisionists worry that public acceptance of the moral equality principle makes war more likely by allowing soldiers to justify participation in unjust wars. McMahan argues, for example, that traditional just war theory's “assurance that unjust combatants do no wrong provided they follow the rules makes it easier for governments to initiate unjust wars. The Theory cannot offer any moral reason why a person ought not to fight in an unjust war, no matter how criminal.”Footnote 9

Moreover, studying public attitudes about moral equivalence can yield important insights into human moral intuitions. Understanding these intuitions may, in turn, provide clues to the origins and future evolution of international norms. Establishing a correspondence between normative theory and our moral intuitions is also important because philosophers frequently rely on discrepancies between the two to identify flaws in theories, or to identify concepts that require further elucidation.Footnote 10

Finally, since just war doctrine informs the existing laws of war, the debate over moral equivalence has significant implications for the international legal framework we rely upon to hold combatants and political elites accountable for their actions. Indeed, the principle of moral equality is enshrined in the preamble to Additional Protocol I of the Geneva Conventions, adopted in 1977, which affirms that the Geneva Conventions must be applied “without any adverse distinction based on the nature or origin of the armed conflict or on the causes espoused by or attributed to the Parties to the conflict.”Footnote 11 Evidence from nonwar contexts also suggests that people are more willing to comply with or report violations of laws when those laws coincide with their preexisting moral beliefs.Footnote 12 Whether the American public believes that soldiers fighting for unjust causes have the same rights and responsibilities as soldiers fighting for just causes, therefore, could influence what kind of justice the public is likely to demand, both for captured foreign prisoners and for U.S. soldiers accused of violating the laws of war. Our research, therefore, provides insights into debates among just war theorists and legal scholars about the degree to which international law should reflect the moral instincts of ordinary citizens and soldiers.

In this article, we report three main findings from an original survey experiment we conducted on a representative sample of 750 American citizens in 2014.Footnote 13 First, we provide strong evidence that most Americans reject the traditionalists’ view of the moral equality of combatants. In our experiment, the public was much more willing to describe soldiers as acting unethically when the war's cause was unjust than when it was just—even when the soldiers’ behavior in each war was identical. Judgments about just cause, in other words, significantly influence Americans’ moral judgments about just or unjust conduct in war. Second, we find that the public's views are not strongly influenced by the kinds of contextual factors that most revisionists argue ought to mitigate individual soldiers’ moral responsibility for participation in unjust wars. For example, Americans were not significantly more likely to judge soldiers’ participation in an unjust war as ethical when they were depicted as reluctant conscripts rather than enthusiastic volunteers. Third, large numbers of Americans express support for policies regarding punishment for wartime decisions that most revisionist scholars do not endorse. A majority of the public, for example, approved of imprisoning all soldiers for their participation in unjust wars, even when the soldiers did not violate the rules of jus in bello. We also found that Americans were also much more willing to describe soldiers who participate in unambiguous war crimes as behaving ethically when they were fighting for a just cause than when they were fighting for an unjust cause. Indeed, more than a third of our subjects agreed that soldiers who executed unarmed women and children had “acted ethically” if they were fighting for a just cause, and half of our subjects disapproved of punishing these soldiers for committing such a war crime.

Taken together, these findings are disturbing. They suggest that just war theory is not a simple codification of widely held moral instincts. On the contrary, just war doctrine serves as a check on those instincts and a practical source of guidance in times of war when, as the history of warfare has repeatedly shown, our instincts can lead to atrocity. These findings, therefore, suggest that changing the laws of armed conflict to reflect revisionist just war principles would likely produce more, not less, unethical behavior in war.

The remainder of this article is divided into five main sections. In the first section, we review the just war theory literature on moral equality and derive several hypotheses from it that can serve as tests of the extent to which the public accepts traditional or revisionist moral logic. In the second section, we describe the original survey experiment that we designed to evaluate these hypotheses. In the third section, we report the empirical findings of our survey experiments. A fourth section discusses the implications of these findings for future research and policy. The final section discusses the significance of moral intuitions for competing interpretations of just war doctrine.

The Principle of Moral Equality in the Literature on the Ethics of War

Traditional interpretations of just war theory hold that the justice of a war's cause should remain separate from the conduct of those who fight in it. Thus, this view maintains that it is possible for soldiers to wage an unjust war justly and to wage a just war unjustly. As Walzer writes, “The rules of war apply with equal force to aggressors and their adversaries. … Soldiers fighting for an aggressor state are not themselves criminals: hence their rights are the same as those of their opponents. Soldiers fighting against an aggressor state have no license to become criminals: hence they are subject to the same restraints as their opponents.”Footnote 14

Traditional arguments for the principle of the moral equality of combatants rely on two critical distinctions. The most important distinction is between the rules that govern the use of violence in domestic life in times of peace and those that apply in times of war. In war, traditionalists argue, all soldiers have lost their personal right to life and liberty, regardless of their motives or the side on which they fight. In contrast, in ordinary life, moral responsibility is judged on an individual basis, and the particular motives and intentions of the individuals who engage in violence are critical to those judgments. There is no assumption of moral equivalence, for example, between a criminal who kills a homeowner in the course of an armed robbery and a homeowner who kills a robber in self-defense. Walzer, however, contends that “war as an activity … has no equivalent in a settled civil society. It is not like an armed robbery, for example, even when its ends are similar in kind.”Footnote 15 For Walzer, a soldier “is not a member of a robber band, a willful wrongdoer, but a loyal and obedient subject and citizen, acting sometimes at great personal risk in a way he thinks is right.”Footnote 16

The second important distinction is between the ethical rules that apply to the soldiers who fight in wars and the rules that govern the political leaders who have the power to initiate wars. In the traditional view, leaders are responsible for the decision to go to war, whereas soldiers are responsible only for their actions on the battlefield. Thus, Walzer quotes approvingly the soldier in Shakespeare's Henry V who says: “We know enough if we know we are the king's men. If his cause be wrong, our obedience to the king wipes the crime of it out of us.”Footnote 17

Traditionalists have offered a variety of defenses for these claims, but many argue that ordinary soldiers simply lack access to the information required to judge whether a particular war has a just cause.Footnote 18 “Combatants,” Henry Shue argues, “have neither the information nor the opportunity for reflection necessary for making such a multitude of individual judgments about unknown and often unseen/unheard but deadly adversaries, and a requirement of making such impossible judgments is inappropriate to the circumstances of war.”Footnote 19 To complicate matters further, many wars are what Seth Lazar calls “morally heterogeneous,” in which “unjust combatants might contribute to limited just goals, while just combatants might contribute to unjust ones.”Footnote 20 Frequently, for example, combatants on the side with the unjust cause may fight to defend their own civilians from unjust attacks by soldiers on the side with the just cause.Footnote 21 Some soldiers might even join wars they recognize to be unjust with the explicit intent of mitigating the harms the war might beget.

Both Yitzhak Benbaji and Neil Renic contend that, given these realities, combatants on both sides tacitly agree to fight under the assumption of moral equality since this agreement is preferable to the alternative in which soldiers have to determine whether their war's cause is just and, if it is not, risk facing punishment after the war for their participation in it.Footnote 22 Permitting individual soldiers to determine whether or not a war is just could also undermine the kind of general obedience upon which military organizations depend, and could render just states, especially democracies, dangerously vulnerable to attack while their soldiers deliberate about whether or not to take up arms. Given these constraints, many traditionalists argue, the soldier's duty to defend his or her state outweighs their individual duty to refrain from advancing a potentially unjust cause.

In contesting the validity of the moral equality principle, revisionist scholars question both of these key distinctions of traditional just war theory. Most revisionists reject the notion that a separate moral code ought to regulate violence in war and in peace. As McMahan writes, “The difference between war and other forms of conflict is a difference only of degree and thus the moral principles that govern killing in lesser forms of conflict govern killing in war as well. A state of war makes no difference other than to make the application of the relevant principles more complicated and difficult.”Footnote 23 Revisionists tend to see war as a collection of discrete acts of violence, each of which can, at least in principle, be judged individually. From this perspective, our thinking about the morality of killing in war should be derived directly from principles of the morality of killing in ordinary life, in which the justice of an individual's cause or motive has clear significance for how we judge his or her violent actions carried out in pursuit of that cause. A homeowner who confronts an armed robber who has entered his home is permitted to use violence to protect his family and property, but the robber cannot claim the right to use violence to defend himself from the homeowner. The robber, in revisionist terminology, is morally liable to defensive violence while the homeowner is not. By the same logic, revisionists contend, soldiers fighting in an unjust war of aggression do not have the same rights to kill as soldiers seeking to defend their state from that aggression.

The revisionists’ rejection of the distinction between the morality of killing in war and the morality of killing in peace leads directly to the rejection of the traditionalists’ categorical division of responsibility between the leaders who authorize war and the soldiers who wage it. If in war, as in ordinary life, judgments about the justice of one's cause influence judgments about the justice of one's actions in pursuit of that cause, why should individual soldiers be judged only by their adherence to jus in bello standards? David Rodin reasons that if “an aggressive war is fought within the bounds of jus in bello, then the just war theory is committed to the seemingly paradoxical position that the war taken as a whole is a crime, yet that each of the individual acts which together constitute the aggressive war are entirely lawful. … It seems plausible to conclude that soldiers, and not just sovereigns, are responsible for the aggressive wars in which they engage.”Footnote 24

Some revisionists also believe that the rules of jus in bello are in need of reform to include a new definition of noncombatants in order to exclude civilians who actively contribute to an unjust war, such as political propagandists or munitions workers.Footnote 25 Still, for all revisionists, a just cause is not a license for intentionally killing morally innocent civilians who pose no threat.Footnote 26 As McMahan succinctly puts it, “That a just combatant's action may serve a just cause does not mean that he or she may treat anyone as fair game.”Footnote 27

Although revisionists question the strict moral division of responsibility between soldiers and sovereigns, their focus on individual responsibility permits certain contextual factors to reduce individual soldiers’ moral responsibility for participation in unjust wars. Most obviously, in the real world, many combatants are unwilling conscripts and possess few practical options for refusing participation in wars they might recognize as unjust. Moreover, combatants frequently lack access to the kinds of information or training necessary to judge whether the cause of a particular war is just or unjust. To return to the domestic robbery analogy, we might judge killing by an armed robber less harshly if it is proven that the robber had been blackmailed into taking part in the robbery or deceived by a trusted authority into believing that the homeowner posed an imminent threat to other innocent people. McMahan notes that “revisionists recognize that combatants act under duress and in conditions of factual and moral uncertainty. These mitigating conditions usually diminish their responsibility for the wrongs they do.” Thus, he concludes that “it would be both unfair and counterproductive to subject soldiers to legal punishment for mere participation in an unjust war.”Footnote 28

A serious complication that arises from the revisionist perspective on the ethics of war—and one that is acknowledged by most revisionist scholars—is the practical difficulty of applying anything resembling the revisionist ethical framework in an actual war. Since most revisionists argue that liability for participation in war should be assigned individually based on each soldier's (or civilian's) moral responsibility, the evidentiary burden of determining whether particular actions in war are just or unjust would be overwhelming and patently incompatible with the exigencies of war. Even after a war has ended, determining the degree of responsibility for thousands or even millions of individual participants so as to justify punishment or clemency would strain any plausible system of justice. Worse, since the world lacks an authoritative judicial body that could adjudicate rival claims about the justice of war causes, in practice states would simply be left to judge the claims themselves. Revisionists concede that there is no reason to expect that most states would do so objectively or would willingly submit to international courts trying to impose their judgment.Footnote 29

To avoid the worrisome practical implications that stem from rejecting the two distinctions that underpin the moral equivalence principle, therefore, revisionist scholars have introduced a third distinction that lies between the laws of war and what McMahan calls the “deep morality of war.” As McMahan writes:

The deep morality of war is not an account of the laws of war. The formulation of the laws of war is a wholly different task, one that I have not attempted and that has to be carried out with a view to the consequences of the adoption and enforcement of the laws or conventions. It is, indeed, entirely clear that the laws of war must diverge significantly from the deep morality of war.Footnote 30

In fact, McMahan concludes that the existing laws of war, including the legal equality of combatants, should probably be preserved for the foreseeable future.Footnote 31

The preceding discussion leads to the following four hypotheses regarding public opinion on the principle of moral equality of combatants:

Hypothesis 1:

The more the public's moral reasoning accords with traditional interpretations of just war theory, the more likely it will be to judge the actions of combatants fighting for a just cause as morally equal to the same actions taken by combatants fighting for an unjust cause.

Hypothesis 2:

The more the public's moral reasoning accords with traditional interpretations of just war theory, the more likely it will be to judge the actions of conscripted combatants fighting for an unjust cause as morally equivalent to the same actions of volunteer combatants fighting for an unjust cause.

Hypothesis 3:

The more the public's moral reasoning accords with traditional interpretations of just war theory, the more likely it will be to hold leaders ethically accountable for initiating unjust wars and the less likely it will be to hold individual combatants accountable for participating in them.

Hypothesis 4:

The more the public's moral reasoning accords with revisionist interpretations of just war theory, the more likely it will be to differentiate between the moral and the legal responsibility of combatants who participate in war.

Research Design

Few scholars have probed American attitudes on just war theory principles and, to our knowledge, none have investigated the American public's views on the moral equality of combatants.Footnote 32 Nevertheless, public opinion surveys have occasionally asked Americans about their views on issues that may be relevant to the moral equality debate. Polls show, for example, that even citizens who oppose particular American wars usually feel they should “support the troops” who fight in them. Indeed, a survey conducted during the 1991 Gulf War shows that of the 24 percent of Americans who opposed the American invasion, only 4 percent (or 1 percent of all those polled) said they did not support the American troops fighting in Iraq.Footnote 33 Similarly, a 2006 poll regarding America's ongoing counterinsurgency in Iraq finds that 77 percent of Americans agreed that it was possible to “support the troops fighting in Iraq and still criticize George W. Bush's policies in Iraq.”Footnote 34 These surveys suggest that Americans can separate their judgments about the justice, or at least wisdom, of a war from their views about the morality of the conduct of U.S. troops who fight in it.

These surveys, however, did not explore whether the public believed that American troops were adhering to the rules of jus in bello, nor can they tell us whether the public would have supported the troops if the war had more clearly violated jus ad bellum considerations. Nor do they shed light on whether these views simply reflect patriotic favoritism toward fellow Americans or reflect a more general ethical perspective that might extend to foreign troops as well. Even if we could compare polls from two or more separate wars in which the public reached different conclusions about the justness of the wars’ causes or of the soldiers’ conduct, it would be impossible to isolate the causal relationships between these attitudes. In the real world, any two wars differ in a large number of potentially relevant aspects, making it impossible to attribute differences in the public's ethical assessments of different wars to any one particular factor.

To test the hypotheses described above, therefore, we conducted an original survey experiment in August 2014 on a large representative sample of American citizens over the age of eighteen. Unlike public opinion polls that inquire about particular wars that are fought in the real world, using a survey experiment allowed us to construct hypothetical scenarios in which we could hold relevant facts about the war (for example, the stakes of the war) constant while varying only one aspect of the conflict (such as the justice of the cause or the soldiers’ compliance with jus in bello conditions). This design enabled us to isolate the effects of beliefs about the justice of the war's cause on the public's ethical judgments about the conduct of combatants and the moral responsibility of leaders.

To conduct this survey, we contracted with YouGov, an Internet polling and experimental research firm. YouGov utilizes a technique called “sample matching” to approximate a representative sample.Footnote 35 This sampling technique has been shown to meet or exceed the performance of surveys based on more traditional telephone polling techniques.Footnote 36 We chose to focus the stories we used in the survey on a hypothetical conflict scenario, using two imaginary countries to help minimize the possibility that the subjects’ knowledge of either country's previous behavior or their subjective loyalties to one side might bias their ethical judgments. If the country initiating a war of aggression was the United States, an American ally, or even a country with close cultural ties to the United States, for example, American citizens might be more willing to judge the decision to go to war as just. This bias would therefore mask the public's deeper moral intuitions about the relationship between the justice of the war and the ethics of soldiers’ conduct, the focus of our study. We acknowledge that utilizing imaginary countries might introduce other problems, especially concerns about external validity, which is how these public intuitions would play out in specific real wars. As we discuss in the conclusion, however, we think these biases render most of our conclusions conservative. Compared to our survey results, in a real-world scenario Americans might be even more willing to excuse the misdeeds of U.S. troops, for example, than those of foreign troops, regardless of whether or not the U.S. troops were fighting for a just or unjust cause.

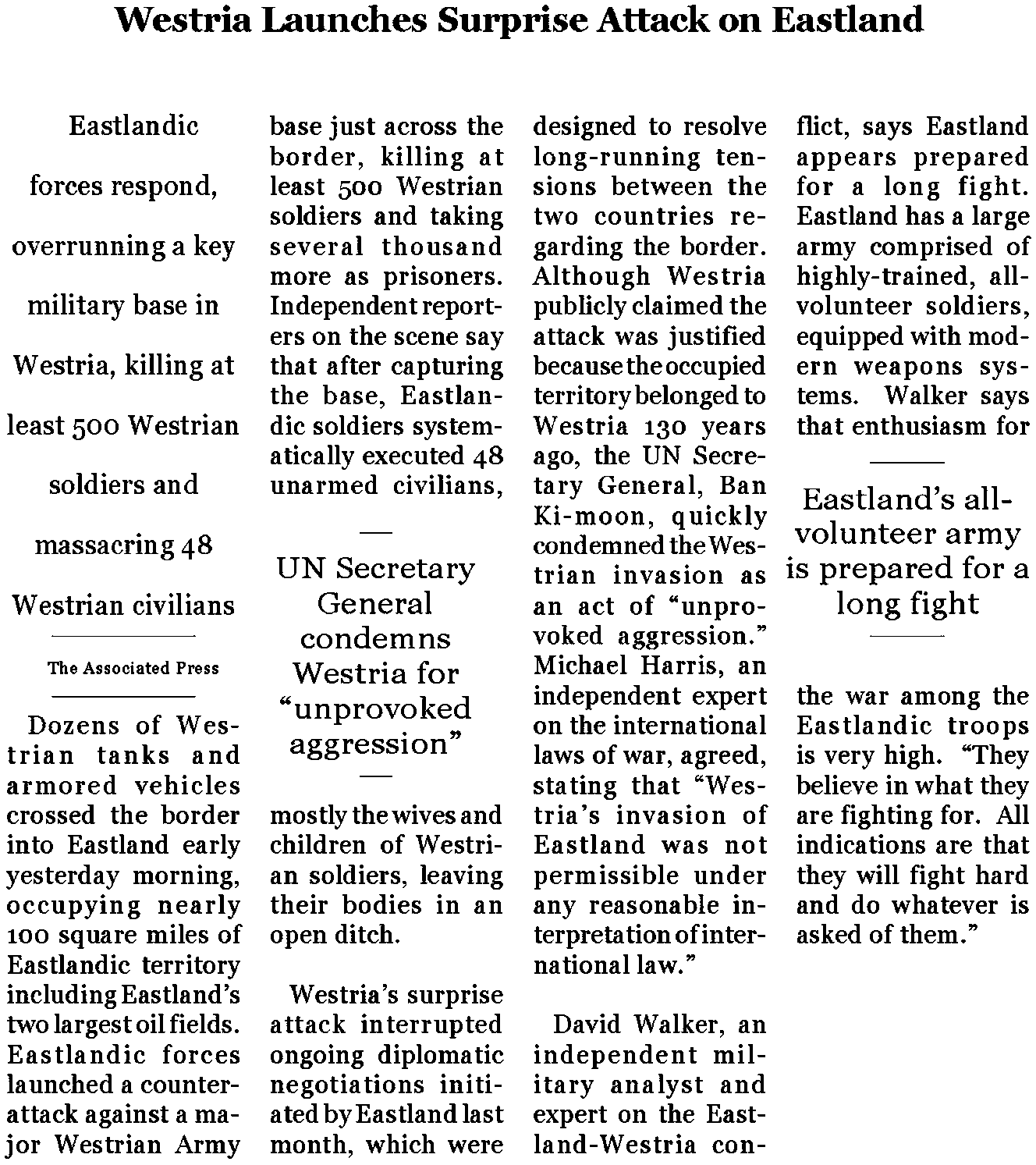

Our experiment included five unique conditions. For each, subjects were each randomly assigned to read a different news story about a hypothetical conflict between two imaginary countries called “Eastland” and “Westria,” described as “large countries located thousands of miles from the United States,”Footnote 37 making it unlikely that subjects would identify either country as the United States itself. It is impossible to know whether the names Westria and Eastland might have stimulated positive or negative connotations in the minds of some subjects. If subjects tended to have more favorable views of Westria because of unconscious associations with the Western world, this could potentially decrease absolute levels of support for Eastland's leaders or soldiers across all conditions. We found high levels of support for Eastland when its cause was described as just, however, suggesting that the labels did not influence our basic findings. Regardless, since we used the same names in all of our conditions, the differences in observed attitudes across conditions, which are the focus of this article, should remain valid.

Approximately 150 subjects were assigned to each condition and each subject read only one story. Subjects were told to read the story carefully and were urged to “imagine how you would feel about these events if they were happening in the real world today.” To increase the realism of the experience, the stories were constructed to look like typical newspaper stories with a byline similar to that of a well-known news agency. The full stories are included in the appendix found at the end of this article and all survey questions and additional data are in the online appendix.Footnote 38

Since the debate between traditionalists and revisionists focuses on the interaction between the justice of a war's cause and the conduct of combatants, our first task was to choose the just and unjust causes for which each side in our hypothetical conflict scenario would fight. Just war theory scholars have engaged in intense debates about the specific motives that can justify war. Although there is little agreement on the justice of initiating war in thorny cases such as humanitarian intervention, preventive wars, or in response to small attacks on minor interests, virtually all scholars of just war theory accept that self-defense of national territory against major aggression is justified, and that unprovoked aggression against another state's territory is not justified. This position is also enshrined in the UN Charter. In our experimental conditions, therefore, Eastland's cause is unjust when it invades Westria without provocation (thereby interrupting diplomatic negotiations with Westria), occupies one hundred square miles of Westrian territory (including the country's two largest oil fields), and kills five hundred Westrian soldiers during an assault on a Westrian military base. In contrast, Eastland's cause is just when it responds to a Westrian invasion of its country (in which Westria initially conquers Eastlandic territories and oil fields) by performing a counterattack on Westrian territory, including an identical assault on a Westrian military base that leaves five hundred Westrian troops dead.Footnote 39

We also wanted to ensure that subjects in our baseline conditions understood that Eastland's soldiers had abided by the traditional rules of jus in bello, which generally permit the killing of adversary combatants (if they have not surrendered) and forbid the intentional killing of civilians. Thus, in addition to having the news stories describe that five hundred soldiers had been killed, we informed subjects assigned to both the just and unjust conditions that “no civilians were reported killed in the attack.” This construction allowed us to explore subjects’ ethical judgments about an identical event—Eastland's assault on a Westrian military base—while varying the justice of the cause of the war in which the assault takes place.

To reinforce perceptions of the distinction between the just and unjust conditions, we also included quotations in the news stories from two independent and objective observers: then UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and someone described as an “independent expert on the laws of war.” In the unjust war conditions, Secretary-General Ban condemns Eastland's attack as “unprovoked aggression” and the independent legal expert is quoted as saying that “Eastland's invasion of Westria was not permissible under any reasonable interpretation of international law.” In the just war conditions, the quotations are identical to those of the unjust war conditions, but refer instead to “Westria's invasion of Eastland,” to which Eastland has responded with a counterattack.

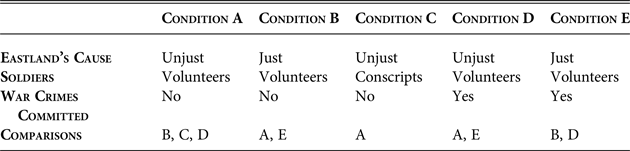

This story structure forms the foundation of all five experimental conditions. It is important to emphasize that the conditions are not “fully crossed,” meaning that it is not possible to directly compare each condition with all the others. The conditions table (Table 1) therefore shows which conditions can be compared to each other appropriately, because only one experimental variable has been changed. As described above, condition A describes Eastland's attack on the Westrian military base as part of an unjust war of aggression. Condition B describes Eastland's counterattack on the Westrian military base as part of a just war of self-defense against aggression. Condition C describes Eastland's attack as unjust (as in condition A), but also emphasizes that members of Eastland's military are “conscripted soldiers drafted through mandatory military service for all males under the age of 30.” Since we were not interested in the effects of conscription, per se, but rather the degree of moral agency of the soldiers, we also needed to emphasize that the conscripts’ participation in the war does not necessarily imply agreement with the motives for war. In this condition, therefore, an expert described as “an independent military analyst” is quoted as observing that “enthusiasm for the war among the Eastlandic troops is very low. ‘They don't really believe in what they are fighting for. But all indications are that they will fight hard and do whatever is asked of them.’”Footnote 40 In all other conditions, Eastland's army is described as being composed of “all-volunteer soldiers.” In these conditions, the military expert emphasizes that “enthusiasm for the war among the Eastlandic troops is very high. ‘They believe in what they are fighting for. All indications are that they will fight hard and do whatever is asked of them.’”Footnote 41

Table 1. Experimental Conditions

Conditions D and E parallel conditions A and B, but include information that describes actions by the volunteer Eastlandic soldiers during the assault on the military base that clearly violate the jus in bello principle of noncombatant immunity. In these stories, it is reported that “independent reporters on the scene say that after capturing the base, Eastlandic soldiers systematically executed 48 unarmed civilians, mostly the wives and children of Westrian soldiers, leaving their bodies in an open ditch.” Since the civilian victims described in this scenario were killed intentionally, did not pose a threat to the Eastlandic soldiers, and had no apparent moral culpability for the war, we know of no just war scholar, whether traditionalist or revisionist, who would judge this killing as morally permissible. The only difference between the two conditions is whether the soldiers who massacred the innocent civilians were fighting for a just or unjust cause. Thus, these conditions allowed us to determine whether the public is more willing to leave unpunished unambiguous war crimes that are committed as part of a just war than it is for an unjust war. Table 1 summarizes the key manipulations in each of the five experimental conditions described above.

After reading one of the news stories, the subjects in each condition were each asked to respond to a series of questions, including questions providing manipulation checks,Footnote 42 questions about the ethical and legal responsibility of the soldiers and leaders, and a series of general questions regarding their attitudes toward the use of force.

Results and Discussion

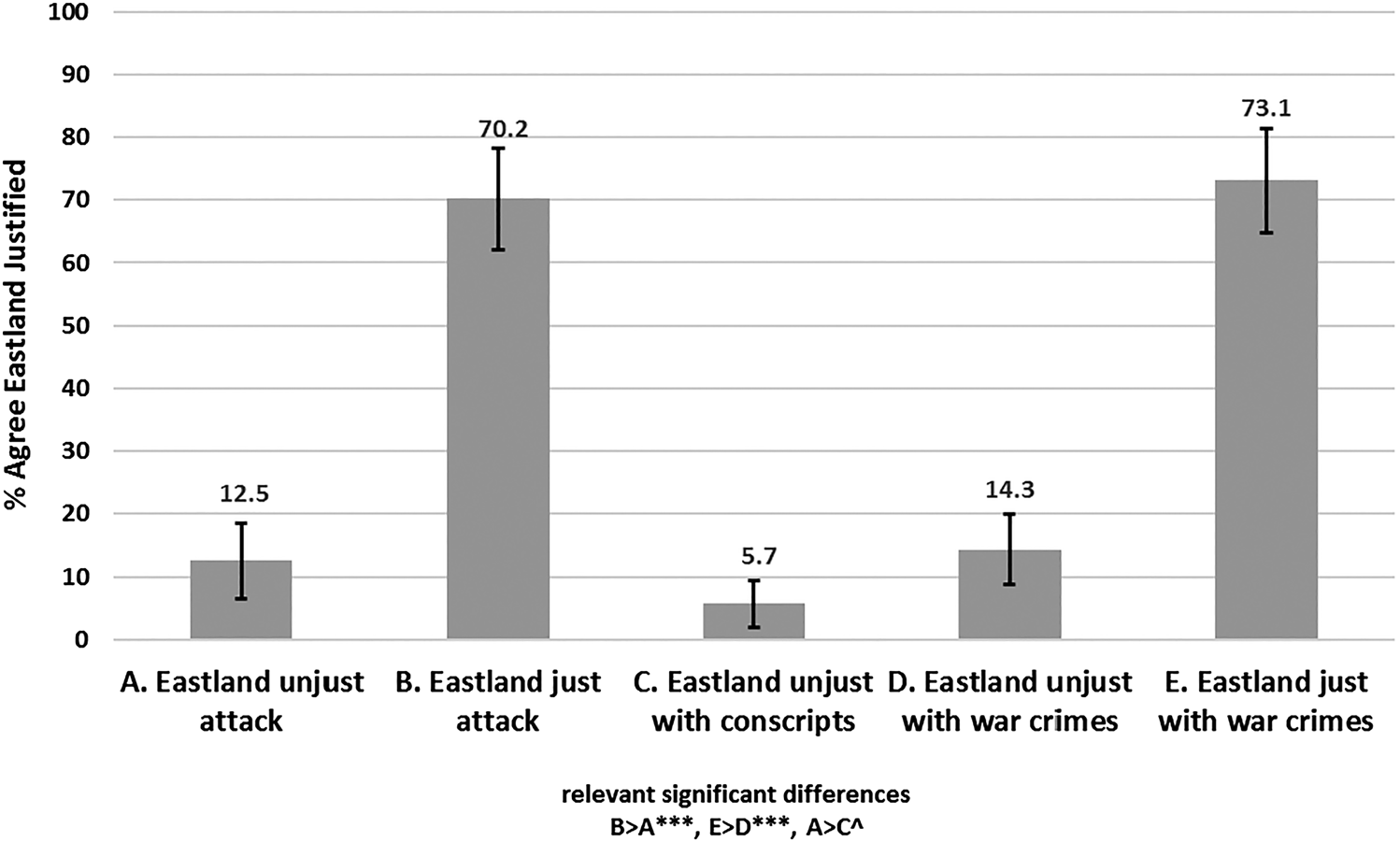

The results presented in figure 1 demonstrate that subjects clearly recognized and accepted the distinction between the just and unjust war scenarios in our experiment. This finding is critical because most of the hypotheses we wished to examine depend upon our ability to manipulate subjects’ perceptions of the justness of the hypothetical war described in the news stories they read. When asked whether “Eastland was justified in fighting against Westria,” subjects in the two just cause conditions (B and E) were much more likely to agree that the fighting was justified than were subjects in the two corresponding unjust conditions (A and D). Indeed, more than five times as many subjects agreed that the attack was justified when Eastland was described as responding in self-defense to a Westrian invasion (conditions B and E) than when Eastland launched an unprovoked attack (conditions A and D). These effects were of strong statistical significance. The use of conscripts by Eastland (condition C) further reduced the percentage of subjects who agreed that the unprovoked attack was justified from 12.5 percent (in condition A) to 5.7 percent. Although this change does not quite meet the standard threshold of statistical significance (p = .06), we speculate that subjects’ lower ethical assessment of the war in the condition where Eastland relied on conscription suggests that some subjects may have held Eastland's leaders morally responsible not only for starting a war of aggression but also for the additional moral wrong of forcing an army of unwilling citizens to wage it.

Figure 1. “Eastland was justified in fighting against Westria.”

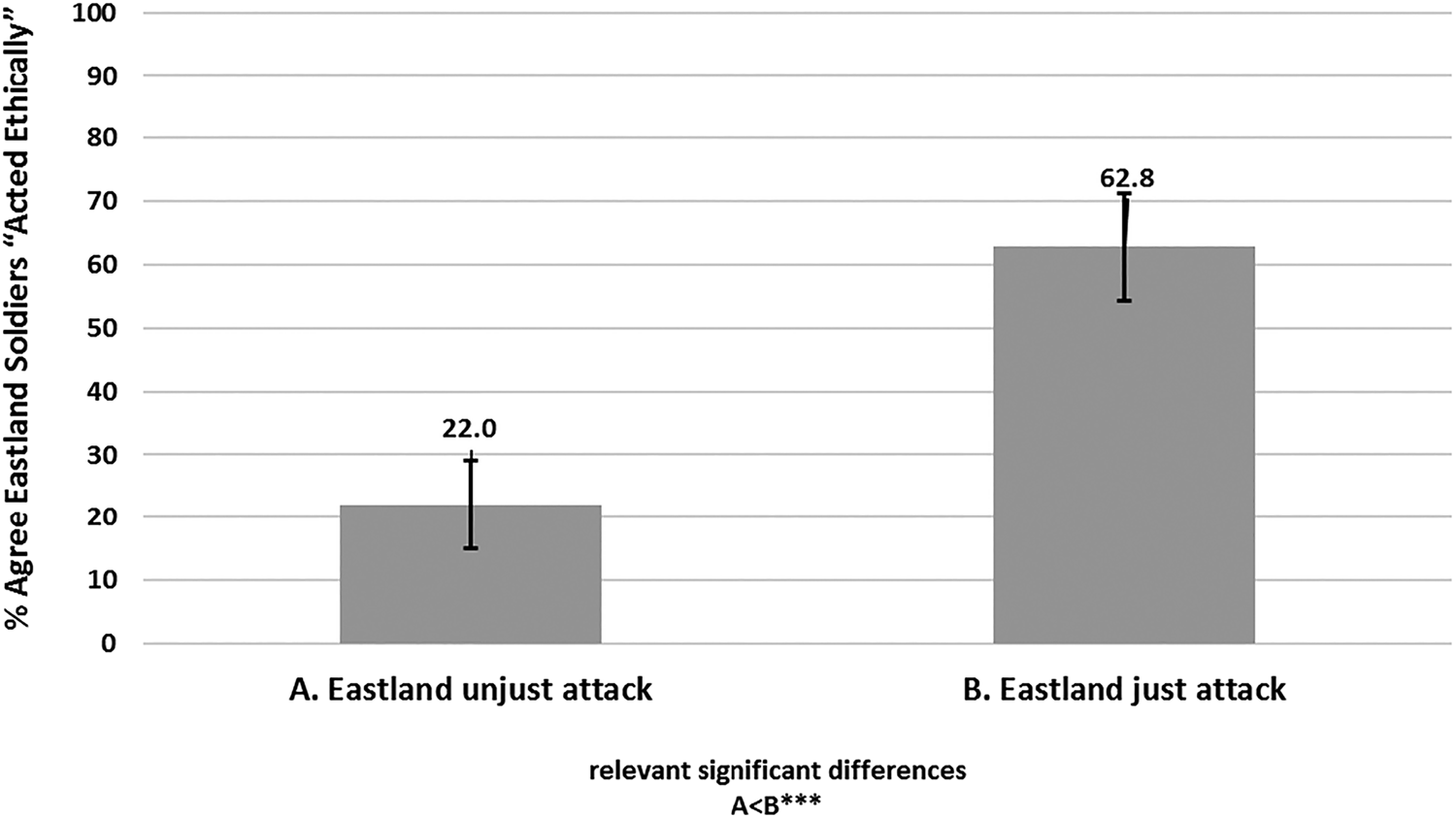

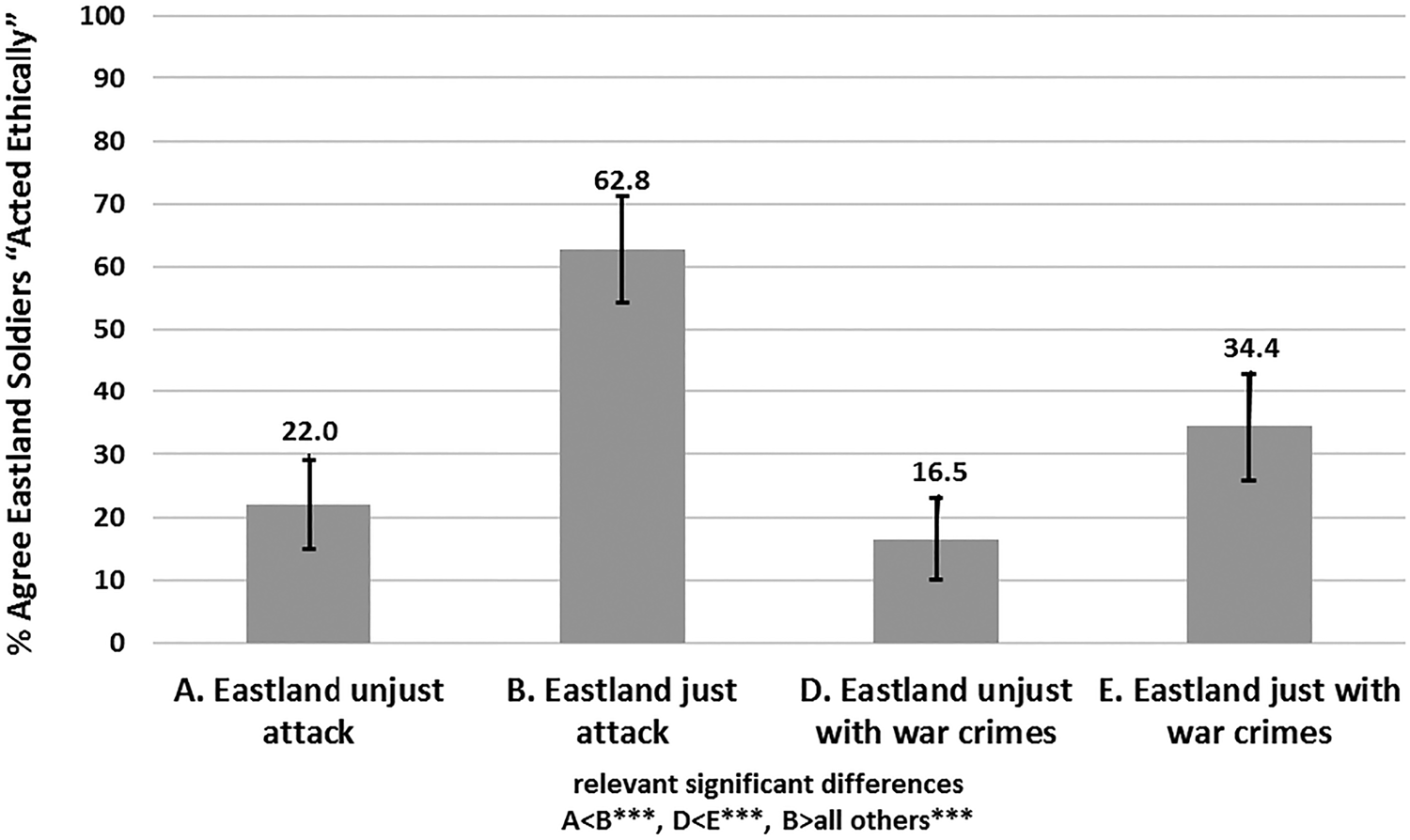

Figure 2 represents the most direct test of hypothesis 1, which posits that if members of the public accept the logic of traditional just war theory, they will judge the actions of combatants fighting for a just cause as morally equal to the same actions taken by combatants fighting for an unjust cause. Counter to the hypothesis and to traditional understandings of just war theory, the results demonstrate that most Americans do not appear to separate jus ad bellum and jus in bello considerations in their assessments of the morality of soldiers during war. On the contrary, almost three times as many subjects (62.8 percent) concluded that the “Eastlandic soldiers who carried out the attack against the Westrian military base acted ethically” when the attack was described as part of a just war of self-defense (condition B) than the amount of subjects (only 22 percent) who thought they acted ethically when the attack was described as part of an unjust war of aggression (condition A).

Figure 2. “The Eastlandic soldiers who carried out the attack against the Westrian military base acted ethically.”

To test whether Americans’ ethical judgments were motivated by the kinds of moral reasoning advanced by the revisionists, we also asked subjects in both conditions how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “Regardless of who was responsible for starting the war, Eastland's soldiers were justified in killing the Westrian troops at the military base because, if they had not done so, the Westrian troops would have killed them.” Although 60.3 percent of subjects agreed with this statement when Eastland's war was portrayed as just, only 31.6 percent agreed when the war was unjust (the difference is significant at p < .001). Most subjects, therefore, accepted the underlying revisionist logic that soldiers who are engaged in an unjust war cannot claim the right of self-defense as justification for killing their just adversaries. This is strong evidence for public support of a central tenet of revisionist just war theory.

Figure 3 presents evidence for whether the influence of just cause extends to a willingness to overlook war crimes committed by soldiers in just wars. Although neither revisionists nor traditionalists advance this proposition, we wanted to explore how far the public might be willing expand the license given to soldiers fighting for a just cause. We found that the public was much more inclined to judge the attack on the military base that included the systematic execution of forty-eight innocent civilians as ethical when it was described as occurring during a just war. Although the suggestion of the killing of innocent civilians did significantly reduce subjects’ assessments that Eastland's soldiers acted ethically in the just war conditions from 62.8 percent (condition B) to 34.4 percent (condition E), the number of subjects who were willing to describe the soldiers who committed war crimes as behaving ethically was more than twice as high in the just cause condition (condition E) than in the unjust cause condition (condition D), rising to 34.4 percent from 16.5 percent. Indeed, the inclusion of the information about war crimes had no statistically significant effect on the assessments of the soldiers’ behavior across the two unjust conditions (condition A vs. condition D). Most subjects, in other words, considered the mere participation of Eastland's soldiers in the unjust war to be so morally wrong that the nature of the soldiers’ conduct in the war was largely irrelevant.

Figure 3. “The Eastlandic soldiers who carried out the attack against the Westrian military base acted ethically.”

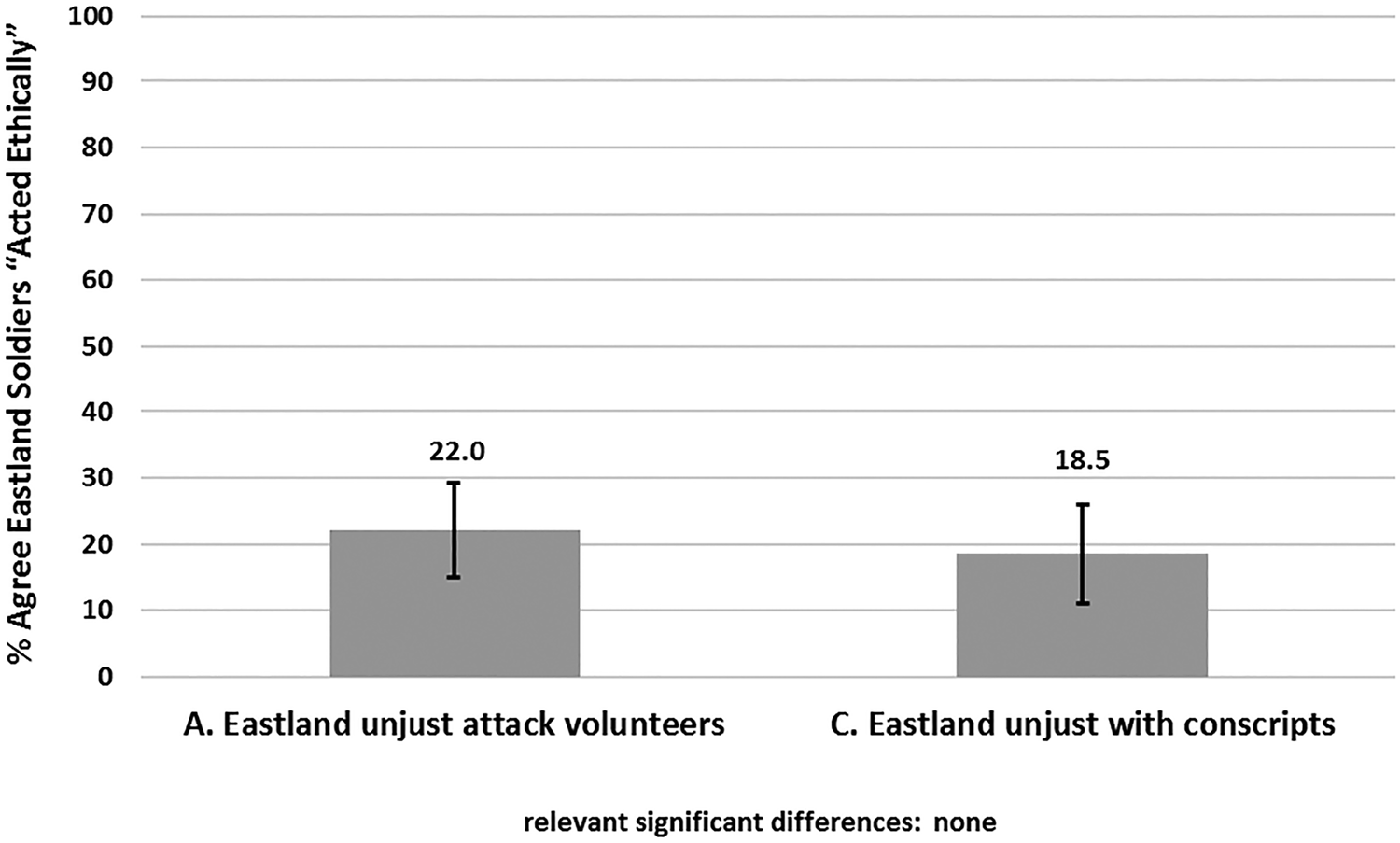

Figure 4 depicts the results of the test of hypothesis 2, which was derived from the revisionist claim that factors such as conscription can reduce the individual ethical responsibility of soldiers who participate in an unjust war. Our results, however, show that subjects’ assessments that the Eastlandic soldiers acted ethically actually declined slightly, from 22 percent in the volunteer condition (condition A) to 18.5 percent in the conscript condition (condition C), although this decline is not statistically significant. Because the Eastlandic soldiers in condition A were described as both volunteers and enthusiastic about the war, while in condition C they were described as both conscripts and unenthusiastic about the war, one might expect that many respondents would strongly view the moral responsibility of the latter group of soldiers fighting in an unjust war differently. They did not. In short, most Americans do not seem to accept the revisionist idea that soldiers who are forced to fight for a cause they do not support are less morally culpable than enthusiastic volunteers.Footnote 43 Averaging across all five conditions, less than half of the public (45 percent) agreed with this statement: “Soldiers in an all-volunteer army are more ethically accountable than soldiers who are drafted into service if they follow orders to fight in a war of aggression.”Footnote 44

Figure 4. “The Eastlandic soldiers who carried out the attack against the Westrian military base acted ethically.”

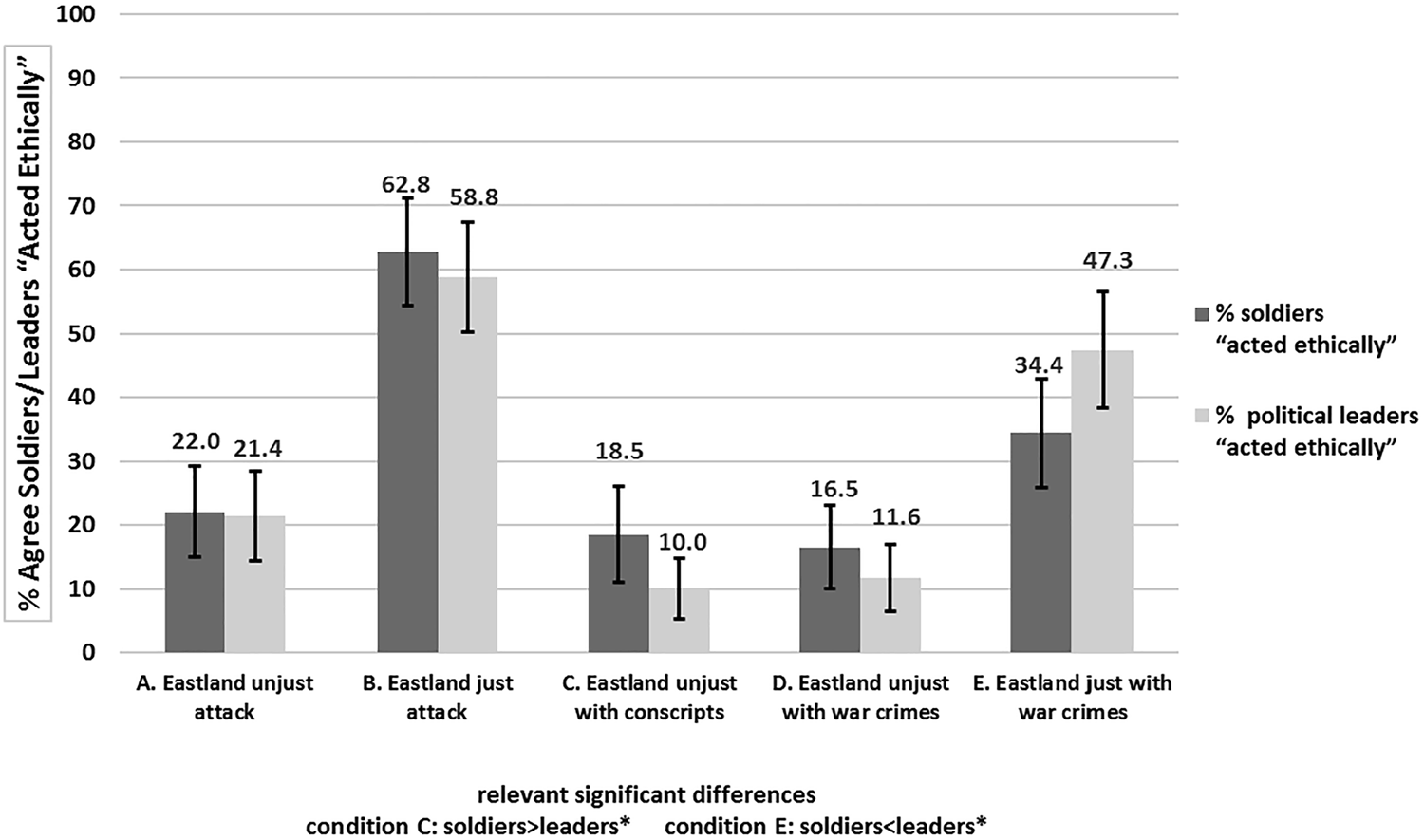

Figure 5 displays the results of the primary test of hypothesis 3. This hypothesis suggests that if the public accepts traditional interpretations of just war theory, respondents will judge that only political elites should be held responsible for assuring that the war has a just cause and soldiers should only be held responsible for their conduct during the war. To assess this hypothesis, we asked subjects whether or not they agreed that “the political leaders of Eastland who ordered the attack against the Westrian military base acted ethically” and compared their answers to their ethical assessments of soldiers’ actions in that attack against Westria. We found mixed support for hypothesis 3. Consistent with the hypothesis, subjects evaluated soldiers’ behavior to be significantly more ethical than that of the leaders when the soldiers were described as unenthusiastic conscripts in an unjust war (condition C). Likewise, we found that subjects judged that the leaders’ behavior was significantly more ethical than that of the soldiers when the soldiers committed war crimes in a war with a just cause. These results suggest that subjects do recognize at least some degree of moral division of labor between soldiers and leaders—placing greater blame on leaders for sending reluctant conscripts into a war of aggression and placing greater blame on soldiers for sullying a just cause by committing atrocities.

Figure 5. Soldiers/Political Leaders “Acted Ethically”

In other ways, however, the results do not reflect the pattern of responses that would be expected if subjects’ beliefs were consistent with traditional just war theory. In condition A, for example, traditional just war theory would maintain that Eastlandic soldiers’ conduct was ethical because they obeyed the rules of jus in bello, while Eastland's leaders behaved unethically because they chose to initiate an unjust war. We find, however, virtually no difference between the U.S. public's assessments of leaders and soldiers in condition A. Even in condition C, where subjects assessed Eastland's conscript soldiers as more ethical than their political leaders, only 18.5 percent of them indicated that the soldiers behaved ethically. Since there was no information in the news story to suggest that Eastland's soldiers violated any jus in bello rules, this number should have been significantly higher if subjects’ beliefs were closely aligned with the traditional perspective on the moral division of responsibility.

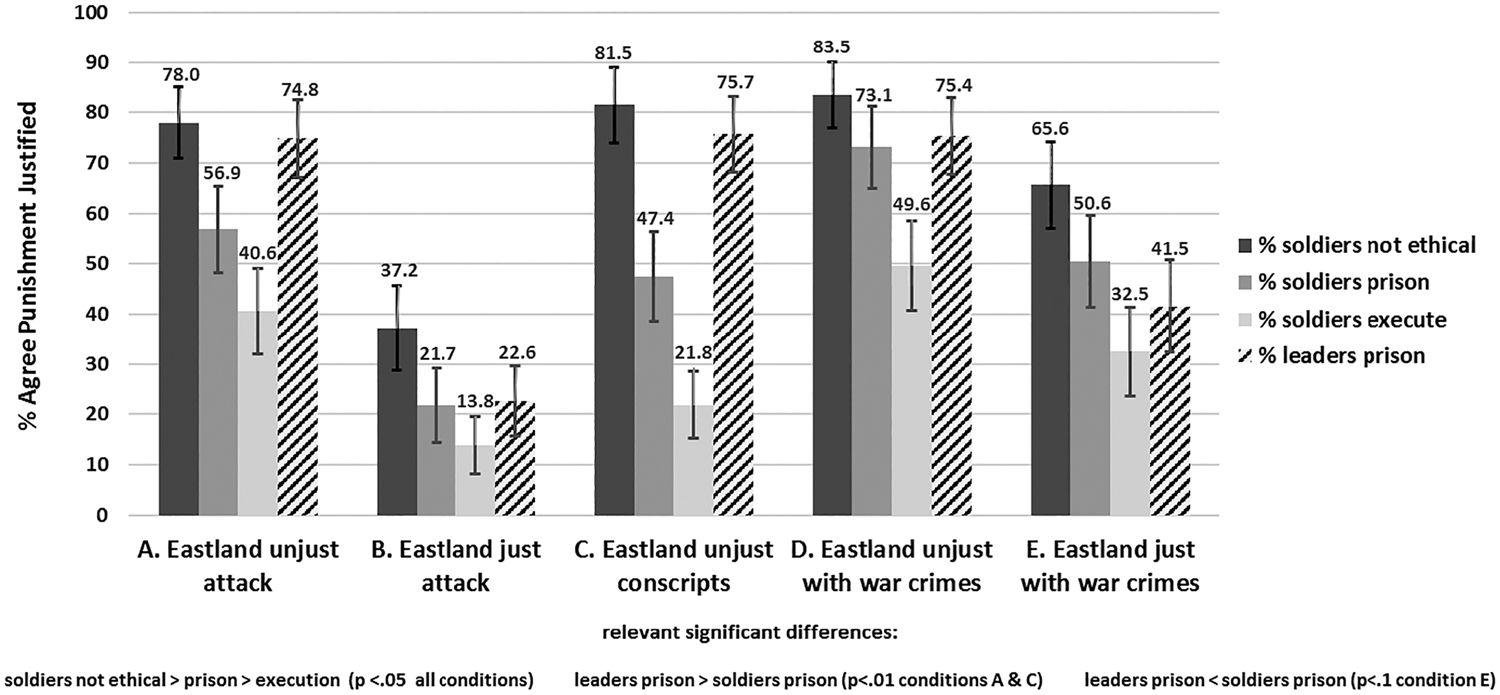

Figure 6 shows the results of the test of hypothesis 4, which we derived from the revisionist argument that the “deep morality” of war is distinct from the laws of war. To explore whether the American public perceives such a distinction, we asked subjects whether they believed that Westria would be justified in seeking to imprison Eastland's leaders and in seeking to imprison or execute the Eastlandic soldiers who had carried out the attack on the Westrian military base. We then compared subjects’ attitudes about these legal punishments to their attitudes about whether the soldiers behaved ethically or unethically.Footnote 45 Once again, we found mixed support for the hypothesis. On the one hand, subjects’ views about the morality of Eastlandic soldiers’ conduct were clearly distinct from their support for the two legal punishments about which we inquired. Across all five conditions, we found statistically significant differences between respondents’ beliefs that Eastland's soldiers acted unethically and their willingness to justify imprisoning or executing the soldiers after the war. On the other hand, their support for legal punishments remained highly correlated with their moral judgments, even in the unjust cause conditions in which the soldiers did not violate laws of war (conditions A and C). Absolute levels of support for legal punishment in the unjust conditions remained high, while support for punishment in the just conditions was surprisingly low. In condition A, for example, 56.9 percent of subjects favored prison terms for Eastland's soldiers simply because they participated in an unjust war. In this condition, 40.6 percent of subjects favored executing the soldiers for their role in the war, as did 21.8 percent even when the soldiers were described as unenthusiastic conscripts (condition C). Perhaps these subjects felt that Eastland's soldiers had a duty to refuse to participate in the war, and instead should have faced the domestic consequences of refusing to fight. Further, 73.1 percent of respondents favored imprisoning soldiers fighting for an unjust cause who committed war crimes and 49.6 percent favored executing them (condition D). Yet, in the just cause condition where soldiers committed war crimes (condition E), only 50.6 percent of subjects felt that those who had executed forty-eight civilians deserved time in prison and only 32.5 percent supported executing them.Footnote 46

Figure 6. “After the war, Westria would be justified in seeking prison terms for/trying to execute the Eastlandic soldiers/leaders who carried out/ordered the attack against its military base.”

Responses in conditions A and C show that subjects were more inclined to imprison leaders for initiating unjust wars than they were to imprison soldiers for fighting in such wars. But notably 41.5 percent of subjects also wanted to imprison leaders on the just side when their troops committed war crimes (condition E)—which is only about 10 percent less than the percentage of subjects who approved of imprisoning the troops themselves. It is possible that some subjects in this condition assumed that the leaders had specifically ordered the massacre or provided loose rules of engagement that made them responsible for what Neta Crawford has called “systemic military atrocities.”Footnote 47 Surprisingly, in condition B a significant number of subjects thought the unjust side, Westria, would be justified in imprisoning the leaders (22.6 percent) and soldiers (21.7 percent) from Eastland who fought a just war in a just manner.Footnote 48

These results suggest that although a minority of Americans do separate their views on the ethics of participation in war from their views on appropriate legal punishments, many Americans do not draw a clear distinction between morality and law. The number of respondents who said it was justifiable for victors to punish enemies regardless of the justice or injustice of their cause or combat behavior was so surprising that we ran a separate survey on another representative sample of the U.S. public to understand what might motivate such views. In this survey, conducted in June 2018, 68 percent of the public said they agreed with the following statement: “In war, the strong do whatever they can and the weak do whatever they must. Ethics just don't apply.” Further, 46 percent of respondents agreed with the statement “After a war, victors have a right to impose their own form of justice on the losers.” Like Thucydides’ Athenian generals, many Americans think might makes right in war.

In order to understand the underlying motives, we also asked respondents in the original survey whether or not they supported the death penalty for convicted murderers in domestic U.S. law. Although approximately two-thirds of all respondents answered yes, subjects who agreed with the death penalty and those who did not were equally willing to imprison soldiers in condition D, in which soldiers massacred civilians while fighting on the unjust side.Footnote 49 In condition E, however, respondents who approved of the death penalty for convicted murderers were twice as likely to say that Eastland's soldiers fighting for a just cause acted ethically despite their involvement in executing women and children. Death penalty supporters were also significantly less willing to support prison terms for these soldiers. These findings resonate with previous research demonstrating that support for the death penalty exerts a powerful effect on the willingness of individuals to support the use of military force.Footnote 50 But the findings also reflect a darker reality: Many Americans appear to approve of “vicarious retribution.”Footnote 51 They are willing to overlook acts of gratuitous killing by soldiers whose cause they believe to be just.

Implications for Research and Policy

Our research contributes to the growing literature that merges moral philosophy with empirical investigation and helps illuminate the nature of human moral reasoning.Footnote 52 As the psychologist Joshua Greene argues, empirical science “can advance ethics by revealing the hidden inner workings of our moral judgments, especially the ones we make intuitively. Once those inner workings are revealed we may have less confidence in some of our judgments and the ethical theories that are explicitly or implicitly based on them.”Footnote 53

Our results indicate that the American public's moral intuitions are generally more consistent with the revisionist perspective on the ethics of war than with traditional just war theory. However, we also find that public opinion deviates in important ways from the precepts of both traditional and revisionist schools of thought. Most Americans, it seems, elevate just cause above virtually all other considerations in assessing the morality of leaders’ or soldiers’ behavior in war. Just as scholars of public opinion have documented a “rally around the flag” effect, in which the public is willing to put aside doubts about the wisdom of war once the fighting has begun, we find evidence of a more general “rally around the cause” effect, in which the public puts aside doubts about soldiers’ conduct as long as it perceives their cause to be just. From this moral perspective, an unjust cause is enough to condemn even soldiers who fight honorably and obey the rules of war, while, for a significant number people, a just cause can excuse what would otherwise be seen as grave atrocities. Both traditional just war theorists and revisionists should find these results disturbing.

More research should be conducted to determine the roots of these beliefs. It is possible that when subjects in our study perceived the war's cause as just, this perception caused them to view the behavior of the soldiers through the same lens. This is consistent with findings from previous research that suggests that individuals can quickly settle on surprisingly stable schemata or “images” of other states (for example, seeing them as “friends” or “enemies”) and that these images can profoundly affect the way they subsequently interpret information about those states.Footnote 54 Our findings may also reflect a cognitive bias that psychologists call “moral licensing.” Moral licensing is the tendency of individuals to allow past moral behavior to excuse subsequent immoral behaviors. Anna Merritt, Daniel Effron, and Benoît Monin posit that “moral self-licensing occurs because good deeds make people feel secure in their moral self-regard. … When people are confident that their past behavior demonstrates compassion, generosity, or a lack of prejudice, they are more likely to act in morally dubious ways without fear of feeling heartless, selfish, or bigoted.”Footnote 55 For many of our subjects, Eastland's just cause at the outset of the war may have become a license for injustice in the prosecution of the war.

This pattern of results is even more surprising because our subjects’ opinions were elicited by reactions to a hypothetical war between imaginary countries. Subjects had no reason to identify personally with Eastland or Westria. In the real world, powerful psychological forces and informational biases likely induce citizens to perceive the cause of their own state as just, even in situations where that judgment might be difficult to justify objectively, and to judge the adversary even more harshly.

Some evidence for this kind of bias was reported in a survey experiment conducted on the Israeli public by Yitzhak Benbaji, Amir Falk, and Yuval Feldman.Footnote 56 Rather than asking subjects to evaluate the conduct of combatants from the perspective of an outside observer, as we did in our experiment, the authors explicitly asked their Israeli subjects to imagine themselves as commanders of an army unit tasked with capturing a strategically important hill. Some subjects were told that their side had started the war by attacking the other side in an effort to take over newly discovered gas deposits (an unjust cause), and others were told to imagine they were on the side defending against this attack (a just cause). Similar to the results from our study on Americans, Benbaji, Falk, and Feldman found that Israeli subjects were more likely to conclude that attacking the hill was morally permissible when subjects imagined themselves on the just side of the conflict. Also consistent with our results, subjects were more willing to support an attack that killed uninvolved civilians when it was part of a defensive war. Interestingly, however, they found that more than half of the subjects, when asked to imagine they were commanders in the aggressor's army, failed to identify the opposing side as just. In addition, there was no difference from our study in the percentage of respondents (65 percent) who thought it was permissible to kill enemy combat soldiers regardless of whether their state was the aggressor or defender. If simply being asked to imagine that one is a soldier on a particular side can bias views of just cause so significantly in a hypothetical scenario, it seems likely that these effects would be much more potent in the real world.

Indeed, public opinion surveys in the United States suggest that Americans are seldom willing to hold American troops responsible for their conduct in war. For example, following the highly publicized trial of Lieutenant William Calley for his role in the 1968 massacre of several hundred civilians in the Vietnamese village of My Lai, only 11 percent of Americans approved of the 1971 court martial finding against Calley.Footnote 57 A Harris poll conducted the same year shows that 35 percent of Americans believed that “Calley was justified in shooting the Vietnamese civilians in My Lai.”Footnote 58

Americans are much more willing, however, to support harsh penalties for wartime behavior when it comes to punishing adversaries.Footnote 59 A 2002 Gallup poll regarding the war in Afghanistan exposed this double standard clearly. The survey asked half of respondents to imagine that “a Taliban soldier were captured during war and held outdoors in an 8-foot by 8-foot cell, and when traveling from one location to another was blindfolded and had his hands bound,” and then asked them, “Would you consider that to be acceptable or unacceptable treatment?” The other half of the sample were asked the same question, substituting the word “American” for “Taliban.” While only 20 percent of subjects found the treatment unacceptable for the Taliban soldier, 46 percent said it would be unacceptable to treat the American that way.Footnote 60

Our results help explain why it is so easy to convince many Americans that individual American soldiers have behaved ethically in war even after they have committed war crimes. The common attitude of “my country, right or wrong” echoes the belief in “our soldiers, right or wrong.” This tendency, however, is not due solely to patriotism or nationalism. It also reflects an intuitive moral license given to soldiers believed to be fighting for a just cause.

Conclusion: Moral Intuitions and Just War Doctrine

Revisionists frequently claim that one of the reasons it is essential to rethink the principle of moral equality is that traditional just war theory is too permissive in terms of war: if more soldiers accepted greater responsibility for the causes of the wars they are being asked to fight in, there would be fewer unjust wars. As McMahan argues, “[Combatants must] abandon the comforting fiction that responsibility for their action lies not with them but with those who're the source of their orders, so that their obedience to the President wipes any crime out of them.”Footnote 61

Our results suggest, however, that the logic of revisionism carries its own risks for how wars are waged. Half of the American public appears to believe that the justice of a war wipes the crime out of war criminals. Seth Lazar argues that the logic of revisionism “opens the floodgates to total war.”Footnote 62 Our empirical findings suggest that revisionism, if put into practice, could undermine the protection of noncombatants during war.

For many Americans, fighting for a just cause provides a moral license to engage in total war. George C. Marshall once argued, “Once an army is involved in war, there is a beast in every fighting man which begins tugging at its chains. And a good officer must learn early on how to keep the beast under control, both in his men and himself.”Footnote 63 Our findings suggest that once war starts, a kind of beast also begins tugging at its chains inside many ordinary American citizens.

Revisionists and traditional just war theorists will likely disagree about whether it is a good or bad thing that the intuitions of most Americans lead them to judge soldiers fighting for just and unjust causes differently. But members of both schools of thought should be concerned that common moral intuitions also include strong elements of vengeance and moral licensing that leave little room for the mitigating considerations that revisionists argue ought to influence our ethical judgments about combatants or the legal consequences of participation in war. Our findings further suggest that just war theory and the laws of war that are partially derived from it should not be conceptualized as efforts to codify our existing moral intuitions about the ethics of killing in war. On the contrary, it seems more important for these concepts to serve as a check on our moral intuitions, which, as the practice of war in the real world has demonstrated time and again, have so often led us to commit and condone terrible deeds that no philosophy should defend.

Appendix: Experimental Conditions

A. Story describing unjust attack by Eastland (condition A)

B. Story describing just attack by Eastland (condition B)

C. Story describing unjust attack by Eastland with conscripts (condition C)

D. Story describing unjust attack by Eastland with war crimes (condition D)

E. Story describing just attack by Eastland with war crimes (condition E)