I

Since the Global Financial Crisis, economic and financial integration has increasingly come under fire and nationalist policies are being vociferously advocated, especially in those countries less able to cope with the challenge of global competition. Integration projects, like the European Union, that are designed to achieve the critical mass needed to succeed internationally often become the scapegoat of political parties wishing to indefinitely delay necessary, though painful, adjustments. Italy is a case in point. Nationalist propaganda depicts it as a giant shackled by malign foreign powers and constantly threatened by international financial conspiracies. Curiously enough, this narrative is paralleled by another at regional level – mostly championed by popular history writers – that, in a similar vein, attributes the lasting economic divide between Northern and Southern Italy to the political subjugation of the South at the hands of the North following unification in the nineteenth century (Capecelatro and Carlo Reference Capecelatro and Carlo1975; Zitara Reference Zitara2011; De Oliveira and Guerriero Reference De Oliveira and Guerriero2018; Benigno and Pinto Reference Benigno and Pinto2019; cf. Nitti Reference Nitti1900).

While scholars still debate the extent of the North–South divide at the time of unification as measured by socioeconomic indicators (Daniele and Malanima Reference Daniele and Malanima2011; Vecchi Reference Vecchi2011; Ciccarelli and Fenoaltea Reference Ciccarelli and Fenoaltea2013; Felice and Vasta Reference Felice and Vasta2015; Cappelli Reference Cappelli2016; Nuvolari and Vasta Reference Nuvolari and Vasta2017; Ciccarelli and Weisdorf Reference Ciccarelli and Weisdorf2018; Felice Reference Felice2018, Reference Felice2019; Federico, Nuvolari and Vasta Reference Federico, Nuvolari and Vasta2019; Di Martino, Felice and Vasta Reference Di Martino, Felice and Vasta2020), financial historians have emphasised the innovative character of Southern finance since the early modern times (Costabile and Neal Reference Costabile and Neal2018), its trials during the difficult transition to an Italian national market (Demarco Reference Demarco1958, Reference Demarco1963; Giuffrida Reference Giuffrida1972–3; De Rosa Reference De Rosa1989–92) and the downsides for the South of monetary integration with the North in what was a far cry from an optimal currency area (Foreman-Peck Reference Foreman-Peck2006; Chiaruttini Reference Chiaruttini2018; Vicquéry Reference Vicquéry2018). Southern banking history, in particular, is traditionally presented as a series of bright achievements before unification and, thereafter, of bitter competition with the Piedmontese National Bank (Banca Nazionale) – the future Bank of Italy – under the malevolent eye of a national government with Northern sympathies.Footnote 1 At first glance, financial history thus seems to lend some support to Neo-Bourbonist claims that Southern markets have been unduly sacrificed in the process of national integration.Footnote 2 This impression is further reinforced by the rise of Genoa and Turin – later followed by Milan – as the beating hearts of Italian finance. Since the North–South divide – whatever its precise extent in the mid-nineteenth century – was certainly much less pronounced than it would later become, so the reasoning goes, the rapid ascent of Northern finance at the expense of the South would not simply reflect better economic fundamentals but rather mirror a deep political imbalance between regions. The relative decline of Naples as a financial centre within the national market would thus be an extreme case of dislocation of economic power from the South – reduced to a periphery – to the new core of political power in the North, set in motion by war.

However, what this narrative, focused as it is on the vicissitudes of the Bank of Naples (Banco di Napoli) and – to a lesser extent – of the Bank of Sicily (Banco di Sicilia), largely forgets is geography and comparative history. In this article I argue that the Achilles’ heels of the Southern financial system – unlike the Piedmontese one – was its severe fragmentation, a fragmentation that was only overcome through the forced opening up of the South to Northern competition. At the same time, however, this original fragmentation made the South unable to compete on an equal footing with the North from the very beginning. It was therefore not so much their integration into a larger market dominated by alien powers but rather a previous lack of integration that crippled Southern banking institutions and business elites in the competition over financial supremacy in a unified Italy. Instead of dramatising their loss of undisputed hegemony in the local market after unification, this interpretation chimes with that of Youssef Cassis (Reference Cassis2006, Reference Cassis2011, Reference Cassis2012, Reference Cassis2018a) on the rise and fall of international financial centres, as they both see wars as catalysts ‘mainly accelerat[ing] long-term processes already under way’ (Cassis Reference Cassis, Cassis and Wójcik2018b, p. 6), rather than as cataclysms capable of reversing them. Moreover, in departing from the South's financial historiography and highlighting the positive rather than the negative aspects of competition, it reframes the turbulent adjustment of Southern banking to the new reality of an Italian market not so much as a crisis but as an opportunity (Cassis Reference Cassis2011) to reshape the local economy.

Clearly, this analysis not only refutes a Neo-Bourbonist reading of Southern financial history that hyperbolises the one offered by the scholarly literature. (The best, or worst, example of this is Zitara (Reference Zitara2011), who contends that Southern banking fell victim to predatory Northern finance, backed by a ruthless colonial government.) It also fundamentally reinterprets what we already know from well-established historiography thanks to new quantitative evidence within a comparative framework. Works like those of Demarco (Reference Demarco1958, Reference Demarco1963), Giuffrida (Reference Giuffrida1972–3) and De Rosa (Reference De Rosa1989–92) – which still represent some of the most significant contributions to nineteenth-century Southern financial history – are treasure-troves of information on the Banks of Naples and Sicily, providing a painstaking chronicle of their evolution. But their overwhelming reliance on archival sources produced by the banks themselves together with their lack of systematic engagement – especially as regards the post-unification period – with quantitative data inevitably conveys a unilateral view of Southern financial history, equated with that of its regional banks. These limitations, in turn, cannot be overcome by simply relying on studies on the National Bank since they have so far entirely neglected its activities in the South.

The comparative approach adopted in this contribution – supported by a novel dataset on the lending activities of the Southern public banks both before and after unification and of the Southern branches of the National Bank – enables me to tell an old story in a new way, by contrasting Piedmontese and Southern markets while also investigating their internal fault lines. Balance-sheet data – whose analysis here is kept to a bare minimum for space reasons (see Chiaruttini (Reference Chiaruttini2020) for further evidence) – unambiguously show the severity of credit undersupply in Southern Italy to the advantage of the public sector before unification and the take-off of Southern markets thereafter due to increased competition. At the same time, archival research concerning both the National Bank and the Southern banks emphasises the role played by politics in financial matters. In the Kingdom of Sardinia, Genoese and Turinese bankers ended up jointly fostering credit development and financial integration as a way to endear themselves to a liberal government committed to economic modernisation but short of money and unable to consistently shield them from competition. In the South, absolutism went hand in hand with a system of public banking putting the needs of the Treasury and of the main cities above those of the provinces and of the economy at large, while the financial estrangement between Naples and Sicily only increased with time. In hindsight, this policy resulted in a slowdown of banking development that put Southern banks and banking elites at a disadvantage when competing with Northern finance in a national market. They proved ready to seize the opportunities offered by the new liberal regime and meet the challenge of competition at a local level but were eventually unable to join forces and rival the power of Northern banking in the national arena.

As regards the article's structure, I first compare Southern and Piedmontese banking on the eve of unification using balance-sheet data of the three largest local credit institutions (Section II), then elucidate their evolution since the Restoration, focusing on their different relationship with the public sector and opposite attitude towards geographical expansion (Section III). Finally, I discuss the transformation of Southern credit markets following unification (Section IV) and conclude with some final remarks (Section V).

II

Before unification, the three largest note-issuing institutions in Italy were the Piedmontese National Bank in the Kingdom of Sardinia, a private bank of issue and direct predecessor of the Bank of Italy, and two public deposit banks in the South, namely the Bank of the Two Sicilies (Banco delle Due Sicilie), later Bank of Naples, and its Sicilian offspring, the future Bank of Sicily. The National Bank had been founded only in late 1849 as a private joint-stock company with the helping hand of Cavour, the mastermind of Italian unification. By contrast, the Southern banks were heir to a long tradition of deposit banking and pawn lending dating back to the sixteenth century. They were not, strictly speaking, banks of issue. Yet they issued transferable deposit notes akin to cheques that circulated across the whole South and could discount bills of exchange and make advances on public securities. After unification, their destiny remained uncertain for a while, as the National Bank was actively seeking, though in vain, to obtain the monopoly of issue and supplant them. In 1866, in the midst of a severe fiscal crisis, the former was able at least to get the exclusive privilege of note inconvertibility until 1874. In 1893 it merged with two smaller Tuscan banks of issue, giving birth to the Bank of Italy, but only in 1926 did its last competitors, the Banks of Naples and Sicily, definitely lose the right to issue notes.

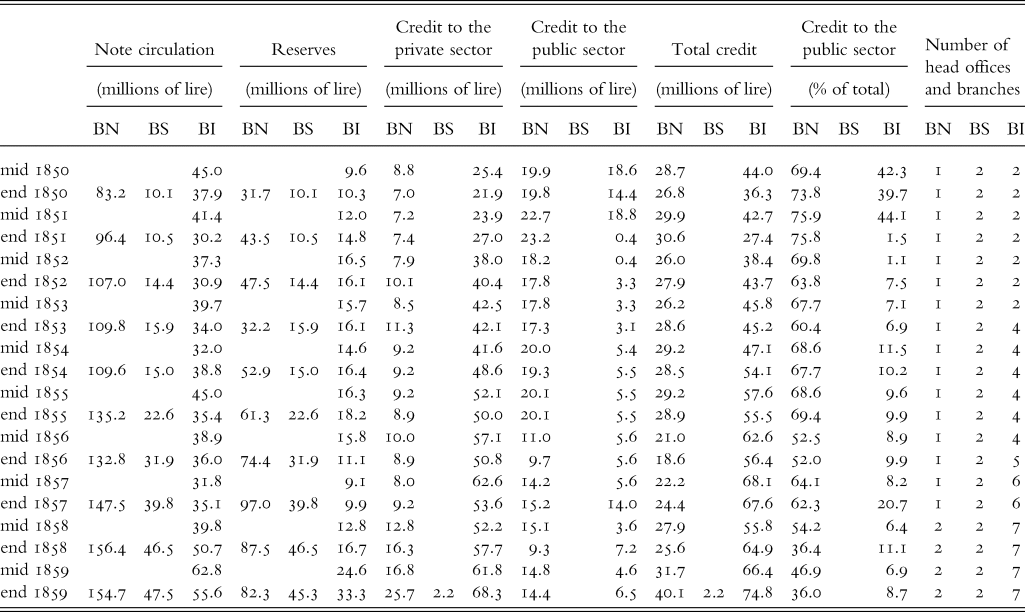

At the end of 1859, just a few months before the annexation of the South to the Kingdom of Italy, the reserves of the Banks of Naples and Sicily were respectively roughly 250 and 140 per cent of those of the National Bank. Their total note circulation was also much larger than that of the Piedmontese bank (Table 1). Moreover, their notes, unlike those of the latter, remained in circulation for an average of three years instead of a few months (Banco di Napoli 1865a, p. 46; Di Nardi Reference Di Nardi1953, p. 25). These figures are truly impressive if we consider that the Kingdom of Sardinia had 5 million inhabitants while the southern mainland 6.8 million and Sicily a bare 2.4 million (SVIMEZ 2011, p. 48). On the surface, the political favour that the National Bank enjoyed in a country unified under Piedmontese leadership and that led it to become in just a few years its most powerful financial institution (in terms of privileges and balance sheets) was therefore hardly compatible with its modest size before unification.Footnote 4 Moreover, though public, the Southern banks were very cautious issuers. After the ravages of the Napoleonic times and brief spells in 1821 and 1848–9, they had always been able to redeem their notes, unlike the National Bank, whose banknotes were declared inconvertible in times of war in 1848 until 1851 and again in 1859 and which always struggled to uphold convertibility (Di Nardi Reference Di Nardi1953, pp. 23–7; Demarco Reference Demarco1958, pp. 193–202; Giuffrida Reference Giuffrida1972, pp. 65–71). Unsurprisingly, then, the claim that Northern financiers and the new Italian government were in many ways just trying to uproot solid, native institutions and substitute them with a shaky bank for political reasons soon gained wide currency. The fact that in the early 1860s the Italian government was seriously contemplating the possibility of reverting the Southern banks to their original function of monts-de-piété and shifting their discounting activities to the National Bank sounded outrageous to many.Footnote 5

Table 1. Note circulation, metal reserves, credit to the public and the private sector and branch network of the Bank of Naples/Bank of the Two Sicilies (BN), the Bank of Sicily (BS) and the National Bank (BI) before Italian unification

Notes: For the sake of comparison with the National Bank, ‘Credit to the private sector’ does not include pawn lending of the Bank of Naples (consumer credit) but only business credit. Figures do not represent annual credit volumes, which are available only for the National Bank, but total outstanding credit.

Sources: author's calculations based on Archivio Storico del Banco di Napoli, Patrimoniale del Banco delle Due Sicilie, Affari diversi appendice (henceforth ASBN/PBDS/AD app.), 23; Archivio Storico della Banca d'Italia, Raccolte diverse, Banca Nazionale nel Regno d'Italia, relazioni annuali (henceforth ASBI/RD/BNRI/RA); Demarco (Reference Demarco1958, p. 470); Giuffrida (Reference Giuffrida1972, pp. 117–18, 133–4).Footnote 3

There were, however, two main structural differences, in terms of ownership and spread of activities, that differentiated the Bourbon and the Piedmontese banking systems, making the former much less competitive in a unified market. Under the Bourbons, the Southern banks were privileged institutions subject to the authority of the finance minister whose credit activities were heavily skewed towards the public sector and a few big cities. By contrast, the National Bank was a fully private company lending in many smaller cities whose support to and from the government had to be constantly renegotiated. Table 1 pitilessly exposes the different workings of the two systems. Thanks to legal privileges, the Southern banks could accumulate deposits on a scale unachievable to a private bank like the National Bank, which still had to familiarise the population with paper money. These massive, unremunerated deposits were mostly used to finance the Treasury. Even in the aftermath of the First War of Italian Independence, when the National Bank was still burdened with a large war loan it had been forced to grant to the government, its involvement with the Treasury in terms of total lending had been much smaller than that of Bourbon banking in peace times. More strikingly, while during the 1850s specie was piling up in the vaults of the Southern banks and the Treasury had lesser needs, credit to the private sector flatlined to increase only two years before the Bourbons’ fall. Over the same period, the National Bank leveraged its fewer resources to provide more and more credit to its private clients. The Southern banks dwarfed the National Bank in liquidity – the National Bank dwarfed them in private credit provision. The following section will tell the story behind these figures.

III

The public nature of the Bourbon banks was not only responsible for their affluence but also for their failed geographic expansion. Proposals for the creation of a network of bank branches across the South had been put forward since the late eighteenth century and constantly delayed because, in a public banking system, their first establishment would have required direct funding from the Treasury (Banco di Napoli 1865a, p. 189; Demarco Reference Demarco1958, p. 330; Reference Demarco1996, pp. 229–52). Outside Naples, bank facilities were badly needed. For decades provinces and towns had been pleading with the government for a branch of the Bank of the Two Sicilies (Demarco Reference Demarco1958, pp. 316–18, 330–2; Ostuni Reference Ostuni1992, p. 86; Chiaruttini Reference Chiaruttini2019, pp. 56–66). What they got instead were mostly corn banks (monti frumentari) providing loans of seed to smallholders and mushrooming in the South since the Restoration (De Matteo Reference De Matteo2013, p. 109) – or nothing at all. The first branches of the Bank of the Two Sicilies were opened in Palermo and Messina between 1844 and 1846. For over a decade they merely worked as deposit banks, starting to lend only in 1859, when the Sicilian Treasury eventually endowed them with an operating fund. The first branch on the mainland, in Bari, was founded as late as 1858 (Table 1).

In some towns, like Palmi and Gerace in Calabria, direct intervention by the state would have been providential, for the few wealthy landowners or merchants who had the means to found a bank profited more from the undersupply of credit than from financial development.Footnote 6 The management of the Bank of the Two Sicilies was highly unsympathetic to those pleas. It feared the initial costs, possible losses and the managerial and logistical hurdles linked to an expansion in the provinces. Moreover, branching was not needed to ensure the wide circulation of deposit notes. The Bank was the only rightful issuer of paper money and paper money was greatly sought after in a country with bad and dangerous roads and a bulky silver standard (Banco di Napoli 1865b, p. 295). In addition, notes were backed by a general mortgage on state property, were accepted for tax payments and redeemable on demand at any tax office in the country. These offices were often affectionately called by the Bank ‘small banks’ (although they were at best bureaux de change) and a proper bank branch was considered a waste of public money.Footnote 7

The Bank's main goal was cheap public financing. The scarcity of banking institutions outside Naples encouraged the well-to-do to deposit their monies with a privileged institution in exchange for deposit notes as good as gold. Cash accumulation in Naples then eased the direct financing of the Treasury, especially in turbulent times (deposits had been seized in the late 1790s, while later the Crown had to face two major insurrections in 1820–1 and 1848–9). Ready redemption of notes all over the country, direct discounting of Treasury bills out of private deposits and the enhanced marketability of public securities due to the possibility for private clients to pledge them at the Bank, all this was a means to an end – a way of slackening fiscal constraints. Without bank branches, to be sure, the Bank was unable to raise deposits locally. This disadvantage, however, was partially offset by the fact that wealthy provincials could nonetheless deposit their money in Naples and convert their deposit notes into cash everywhere. Furthermore, the absence of branches favoured not only deposit concentration but also trade with Naples. To get paper money one could in fact either open a bank account in Naples or trade, directly or indirectly, with Neapolitans paying in notes. A third possibility was to go to a tax office, although the free conversion of cash into paper, unlike its opposite, was a more controversial issue.Footnote 8

If the Bank, however, had an interest in ensuring the prompt redemption of its notes so as to secure large deposits with which to finance the Treasury, it was less committed to it than a private, non-monopolistic bank of issue with its own branch network would have been. The fact that tax offices and not bank branches were responsible for redemption implied that notes were converted on demand provided there was enough cash left in the local public chests. Only in case of soaring demand was the Bank willing to transfer funds from the capital to the provinces in order to bolster confidence in its notes. But whenever the mismatch between supply and demand was not too large, it did not intervene, obliging provincials to resort to money changers or bribe public officials to get priority of payment – officials who were legally bound to ensure convertibility free of charge without always being provided with the means to do so. As a result, whenever in a province not enough taxes were raised in cash to meet the local demand for both government expenditures in specie (as notes were not legal tender) and note conversion from citizens, provincials saw the value of their paper money depreciate.Footnote 9

Specie concentration in Naples, achieved through a highly restrictive branching policy, benefitted not only the central government but also the largest Neapolitan merchants, the few lucky ones who could rediscount their bills with a bank awash with money, act as credit intermediaries between capital and provinces and even earn a premium on paper in their trades with the latter whenever notes were in high demand. This asymmetry in banking infrastructure mirrored a deep inequality in fiscal policies, whereby 56 to 83.5 per cent of the tax revenues from the provinces, including the poorest ones, ended up in the capital city, where 84 per cent of all expenditures took place. Naples thus continued to be the ‘swollen head of a shrunken skeleton’ decried by Enlightenment economists already a century before (Ostuni Reference Ostuni1992, pp. 324–7, appendix V). The preponderance of Naples was also sustained by the absence of a constitutional regime and the clustering of all major economic interests around the Crown (see Davis Reference Davis1981).

The desire to obtain a constitution and rebalance the political system led in 1848 to the Sicilian revolution, which had fateful consequences for the South's banking development. The revolution broke out shortly after the government finally authorised the Bank's branches in Palermo and Messina to start their credit operations in addition to their deposit and payment services (Demarco Reference Demarco1963, pp. 175–6). The civil war emptied their coffers as well as those of the local Treasury. After the insurrection was quelled, the island obtained administrative autonomy and the two branches were merged into a public bank independent from Naples. But the Sicilian Treasury, burdened with heavy debts to Naples, was now unable to provide the new bank with the initial endowment legally necessary to start lending. Moreover, while previously notes were freely convertible between island and mainland, thereafter the Bank in Naples refused to redeem Sicilian notes, obliging public and private clients to make cross-border payments either in specie or through expensive bills of exchange (Giuffrida Reference Giuffrida1972, pp. 51–78, 87–91). On the mainland, too, public indebtedness remained the chief concern rather than banking development. Only a couple of years before their fall, the Bourbons eventually resuscitated the project of opening bank branches in a few more towns: they only had the time to establish one in Bari before Garibaldi landed in Sicily. Consequently, when the National Bank arrived in the South, following the Piedmontese army, it had to face not one gigantic bank but two separate large banks, one of which, the Bank of Sicily, had begun lending only 13 months before and both of them deprived of a branch network worth the name.

The National Bank had followed a completely different strategy. It had been founded in 1844 as the Bank of Genoa (Banca di Genova) with both Genoese und Turinese capital and had immediately aimed at expanding its business from Genoa to Turin (Conte Reference Conte1990, pp. 50–4; Scatamacchia Reference Scatamacchia2008, pp. 3–31). Proximity and competition had soon spurred Turinese capitalists, among whom was Cavour, to launch a similar bank in their own city. In 1849, the First War of Italian Independence and the inconvertibility of the notes of the Bank of Genoa, imposed by a government in financial distress, had facilitated the merger of the two banks in order to jointly profit from this temporary privilege. Over the following decade, the Piedmontese government, headed by Cavour, tried unsuccessfully to grant substantial privileges to the new bank in order to better avail itself of its services, from its appointment as Treasurer General of the state to the legal tender status for its banknotes (Rossi and Nitti Reference Rossi and Nitti1968, vol. 2, pp. 865–1276; vol. 3, pp. 1525–1780; Conte Reference Conte1990, pp. 122–9, 162–8). However, parliamentary opposition to central banking (the Kingdom of Sardinia, unlike the Two Sicilies, had become a constitutional monarchy in 1848) had derailed those plans, forcing the National Bank to forge its own path to market dominance.

Although Genoese and Turinese bankers were no less afraid than Neapolitans of the risks and costs branching entailed, and were equally conscious of the likely loss of their intermediation profits between main cities and provinces as private financiers, they needed branches to spread their notes across the country and prevent the establishment of competitors.Footnote 10 Branching was moreover warmly encouraged by a constitutional government desirous of pleasing local constituencies (see e.g. Rossi and Nitti Reference Rossi and Nitti1968, vol. 3, pp. 1944–5). As a result, thanks to a massive capital increase the National Bank was able to open five fully operational branches in just six years (Table 1). Branches did not of course enjoy the same freedom of action as the Genoese and Turinese head offices and the governance of the National Bank remained firmly in the hands of Genoese and Turinese capitalists. Nevertheless, provincials now had access to the same banking services as the main cities, while the expansion of the National Bank encouraged the founding of new banks that could rediscount their portfolio with the former (Polsi Reference Polsi1993, pp. 8–28). Even very poor regions, like Sardinia or Savoy, could boast a branch of a bank of issue: the former, one of the National Bank and the latter, two offices of a second much smaller bank, the Bank of Savoy. Moreover, although relationships between the Genoa and Turin head offices were at times tense,Footnote 11 common interests concerning the bank were reinforcing cooperation between local banking elites, who were now more interested in cultivating government favour than in fighting each other.

Branching enabled the National Bank to rapidly expand private lending, which always remained its core business (Table 1). In the South, by contrast, there was something akin to a savings glut. The accumulation of bank deposits in Naples, the self-inflicted impossibility of reinvesting them outside the capital city, besides the competition from private bankers like the Rothschilds (who in the 1820s had opened a branch in the city to help the monarchy access international markets), severely restrained the discounting activities of the Bourbon bank, which often had to struggle to find clients (Demarco Reference Demarco1958, pp. 294–8, 313–14, 389–90). Its cumbersome bureaucracy, a legacy of early modern times, further discouraged them.Footnote 12 At the same time, its public nature and the absence of shareholders made the quest for profit a much less pressing need than it was for the National Bank.Footnote 13 In Sicily, the situation was even more dramatic. Idle deposits soon reached exorbitant proportions, while lending activities, started too late, were ludicrous in comparison, thus vindicating the nineteenth-century liberal view that governments were bad bankers (Banco di Napoli 1865a, p. 166; Camera dei Deputati 1911, vol. 2, pp. 609–10; Rossi and Nitti Reference Rossi and Nitti1968, vol. 2, pp. 988‒9, 1134; vol. 3, p. 1712).

IV

After unification, the National Bank developed a nationwide branch network at lightning speed. Its southward expansion has often been portrayed as a war of extermination against the Southern public banks with the tacit approval or even the active support of the government (Demarco Reference Demarco1963; Giuffrida Reference Giuffrida1972; Capecelatro and Carlo Reference Capecelatro and Carlo1975; De Rosa Reference De Rosa1989, vol. 1). This narrative, however, is severely biased in its disregard of the structural differences between Piedmontese and Bourbon banking, the fate of the provinces, the advantages of competition and modernisation, the role played by Southern politicians in steering banking policies and the perduring conflicts of interests within the South itself between core and peripheral regions.

For the Italian government, the existence of the Southern banks was both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, as moneyed public institutions they were initially forced to offer ready financing to the cash-strapped state. On the other, they further complicated the establishment of a nationwide banking system. The government, confronted with the daunting task of recoinage and vast military and infrastructural expenses, needed a well-branched payment system. The National Bank, thanks to its former experience in branching, was better able to provide it than any other banking institution in Italy. Moreover, the issue and redemption of banknotes, instead of deposit notes, was a business that required just a few employees in comparison with the intricate workings of the Southern banks. Last but not least, self-interest could lead to a profitable cost split between the government and the National Bank. The government could shift part of the expenses linked to its own payments onto a private institution which in turn was glad to undertake any commitment that might bolster its claims to the monopoly of note issue. The National Bank itself was then able to share these costs with the local administrations, as these were willing to help cover the overhead costs of a branch in order to improve local credit conditions.Footnote 14 In a public system like the Southern one, it was the government which had to directly fund new branches, which explains why it was so reluctant to introduce banking services in the provinces when it already had to employ personnel to carry on its own payments.

Furthermore, there was not only a logistic but also a governance issue. The new government had to combine a private banking system in the North with a public one in the South. It could not favour the establishment of a monopolistic joint-stock central bank without destroying the Southern banks, but any such attempt sparked outrage in the South. At the same time, it could not impose the Bourbon solution on the whole country – an unpalatable option for both nationalists and economic liberals. Keeping two separate regional systems was impractical as well as politically unattractive, nor could there be any fair competition between private banks and banks managed by the Treasury. The Italian government had therefore to find a happy medium by somehow reforming and scaling down the Southern banks. In doing so, it followed an economic rationale more than the desire to impose Northern supremacy. After a few unfortunate attempts to convert the Southern banks into mere deposit institutions and leaving discounting activities to the National Bank and other discount houses, the Treasury limited itself to relinquishing their direct management and left them in the hands of boards elected by the local authorities and business associations (Giuffrida Reference Giuffrida1973, pp. 7–19; De Rosa Reference De Rosa1989, vol. 1, pp. 5–8). This compromise was the least damaging for the financial power of the Southern banks, while, in comparison with the Bourbon system, it delegated power to the Southern business community and regional administrations. Nevertheless, it only attenuated, without eliminating, the tensions between public and private banking and made the establishment of a central bank by means of mergers between existing private banks of issue an unattainable goal.

In the unified market the Southern banks certainly lost their privileged status, but not because the government was just the helpless prey to the National Bank's will to power. On the contrary, it had to find a workable way to adapt the Bourbon banking system – a centralised structure with almost no branches controlled by the Treasury of an unelected government – to the new reality of a liberal market. It is therefore unsurprising that many Southern economists and politicians favoured reform and there is no need to regard them as mere collaborationists of the Piedmontese to explain their position. Filippo Cordova, who in 1861 in his capacity as Minister for Agriculture, Industry and Trade tried to reduce the Southern banks to little more than pawnshops, had been an outspoken critic of public banking already in 1848 as Finance Minister of the Sicilian revolutionary government.Footnote 15 One of his successors, the Neapolitan Giovanni Manna, was also against public banking, opposing, in accordance with this view and equally unsuccessfully, the continuation of discounting activities by the Southern banks.Footnote 16 Even a Southern patriot like Nicola Nisco, who would later become one of their staunchest supporters, used to consider them – before getting a seat on the board of the reformed Bank of Naples – old-fashioned institutions soon to be dismantled and in 1861 he had taken the side of the National Bank together with yet another Finance Minister, the Neapolitan Antonio Scialoja.Footnote 17

Nevertheless, it is undeniable that, despite their wealth indicated by bank deposits, Southern business elites had a weaker bargaining position than their Northern counterparts when it came to banking policies, as made abundantly clear by the privilege of inconvertibility granted to the National Bank alone in 1866. But this has much to do with the absence of powerful private – as opposed to public – banks. Even assuming a negative attitude of the new government towards Southern institutions, it would never have been able to wage war against large private joint-stock banks in the South in favour of the National Bank without reneging on its own liberal principles. But such institutions had never come into being in the South. The National Bank was only confronted with the public banks of a defeated government, banks almost without branches, whose private lending was disproportionately low and which were moreover in need of fundamental reform. The absence of a strong banking system was a comparative disadvantage that became immediately clear to Southern businessmen in the wake of unification. In both Naples and Palermo they hastily hatched plans to establish their own joint-stock banks of issue. Nothing came of it (Giuffrida Reference Giuffrida1972, pp. 141–5, 157; Chiaruttini Reference Chiaruttini2019, pp. 215–19, 223–4). They not only had to reckon with the ambivalent stance of the government – lobbied by the National Bank and unsure as regards the question of monopoly versus plurality of note issue – and with the financial chaos resulting from war, annexation and loyalist insurgencies. They were also soon offered the attractive option of jumping on the bandwagon of the National Bank.

In order to expedite the spread of its activities in the South, the National Bank welcomed Southern businessmen on the boards of its new branches with open arms. It was even willing to close both eyes when it came to the number of its shares each board member had to buy and deposit as a guarantee of good management before taking office. Neapolitans had to buy 20 instead of the 30 shares prescribed by the bank's bylaws for a head office, Sicilians just six, in some towns no shares were bought at all until 1865.Footnote 18 The coexistence of the Southern banks with the Southern branches of the National Bank weakened the former as single institutions but empowered the Southern business community, which could now control both types of banks freed from central government interference.Footnote 19 Their influence, however, was stronger within the traditional banks due to their regional character. By contrast, within the National Bank they had to share power. Each head office had three representatives on the National Bank Superior Council. Since in the South there were only two head offices, Naples and Palermo, against five in the Centre-North (Turin, Genoa, Milan, Venice and Florence), Southerners were a minority. But this situation, again, mainly mirrored the highly asymmetric development of financial centres in the South inherited from Bourbon times.

Not only were Southerners underrepresented within the country's future central bank. They were also unable to devise a common strategy. Since 1848 the paths of the Banks of Naples and Sicily had diverged instead of converging and after unification no serious attempt was made to align their interests. Neapolitans and Palermitans were mutually distrustful and the latter were jealous of any advantage the former enjoyed.Footnote 20 In the 1860s a merger was briefly considered but the Bank of Naples could conceive a takeover of the Bank of Sicily only on its own conditions.Footnote 21 This lack of strategic cooperation played into the hands of the National Bank, which was able, for instance, to attack the reserves of the Bank of Naples by exploiting the clearing agreement the latter had with the Bank of Sicily and asking for the conversion of huge amounts of Neapolitan notes on the island. True to a formal agreement but unconcerned with the position of its Neapolitan partner, the Bank of Sicily had continued to pay until the Bank of Naples unilaterally ended the clearing agreement to protect its own reserves (Giuffrida Reference Giuffrida1972, pp. 204–10; De Rosa Reference De Rosa1989, vol. 1, pp. 62–6).

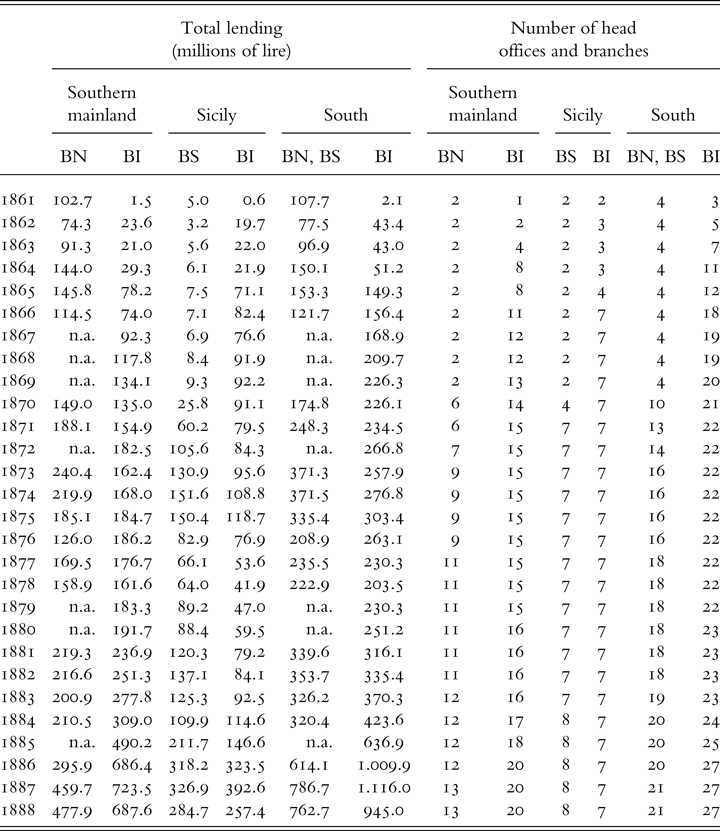

The fragile cohesion of the regional banking elites was also evident in their will to concentrate decisional power in Naples and Palermo at the expense of the rest of the South. To catch up with the National Bank, in the 1870s both Southern banks started to develop their own branch networks (Table 2). The management of the Bank of Naples was, however, concerned about the growing influence provincials could exert within the bank's board and tried in various ways – by limiting the numbers of head offices, discouraging attendance of board meetings and lobbying politicians – to curtail it.Footnote 22 In the same spirit, the Bank of Sicily was wary of expanding northwards, thus diluting the power of Sicilian representatives (Giuffrida Reference Giuffrida1973, pp. 188–9).

Table 2. Bank offices in the South of the Bank of Naples (BN), the Bank of Sicily (BS) and the National Bank (BI) and their annual lending volume

Notes: As in Table 1, ancillary credit activities, like pawn lending and land credit, that in the North were offered not by banks of issue but specialised credit institutions are not included in the lending volume of the Southern banks. Figures for the Bank of Sicily are overestimated, as they include the activities of its branches in Rome (est. 1874) and Milan (est. 1884) (see Piluso Reference Piluso and Asso2017, p. 54). Benevento is not counted as a Southern branch of the National Bank, since the town did not belong to the Two Sicilies. Table 2 ends before the financial bust of the late 1880s to early 1890s.

Sources: author's calculations based on ASBN, Relazioni annuali; ASBI/RD/BNRI/RA; De Mattia (Reference De Mattia1967, vol. 2, tables 17–18) for Sicily.

Taking the perspective of the Southern provinces – which play a marginal role in the literature – not only unveils power conflicts within the South itself which have nothing to do with Northern interference. It also helps rethink the struggle between the National Bank and its Southern rivals. In the early 1860s, the National Bank, a foreign institution little known in the South, had trouble competing with the Southern banks, whose notes circulated much more easily.Footnote 23 The only way in which it could conquer the South was by occupying the space left empty by its competitors: the provinces. In just one decade it opened 20 branches in the South, a third of its entire network (Table 2). Many cities and towns thus got a bank branch for the first time. Transition from informal to formal credit markets was greatly accelerated – all the more so because after a while the Banks of Naples and Sicily also started to open their own branches. In terms of means of payments, provincials could now choose between two slightly different options, deposit notes and banknotes. They had access to bank deposit services. They could discount bills with banks that, because of their desire to spread their own notes, were gladly granting credit. Local branches had to comply with the rules dictated by the headquarters in Naples, Palermo or Florence (where those of the National Bank were located until 1893) but retained much discretionary power nonetheless. The local management could not, for instance, decide how much to lend in the aggregate but could always decide to whom to lend. And if the how much of one branch was not enough, would-be borrowers could often turn to a competing branch in town.

This was a major revolution, concisely captured by Table 2. The aggressive penetration of the National Bank into their home market spurred the Southern banks to chase it in the provinces, progressively expanding both branches and credit volumes. Table 2 also questions the characterisation of the National Bank as a ‘foreign’ institution and of the Southern banks as regional champions. While in terms of governance and ownership the National Bank retained its Northern character (De Mattia Reference De Mattia1978, pp. 696–731, 746–55, 758–64; Scatamacchia Reference Scatamacchia2008, pp. 210–57), it provided almost as much credit in the South as its Southern competitors altogether until the mid 1880s and thereafter even surpassed them. With its branch network it was the only truly national banking institution in Italy but also the one with the highest number of branches in the South, providing its Southern clients with banking services at both a national and local level. Its contribution to credit development was fundamental in the 1860s and nowhere so visible as in Sicily. For years wealthy Sicilians continued to deposit their money with the Bank of Sicily – which in the 1860s had still ₤27m reserves on average – rather than with the National Bank. But in a decade the former provided only 39 per cent of the credit of the latter in Palermo alone and 15 per cent of it if we consider the whole island, before the credit boom of the Bank of Sicily in the 1870s (Chiaruttini Reference Chiaruttini2020, p. 24).

V

In the public debate, economic integration is increasingly regarded with suspicion and economic nationalism extolled as a panacea for local development. In Italy, in particular, the resurgence of nationalist feelings has been accompanied – somehow paradoxically – by widespread disenchantment with the Risorgimento epic. Italian unification is no longer praised as the nation's founding myth. On the contrary, it is often viewed as a war of conquest waged by the North against the South, a notion increasingly captivating popular imagination among fears of being marginalised within Europe as allegedly happened to the South in the Kingdom of Italy almost two centuries ago (Chiaruttini Reference Chiaruttini2020).

In this article I argue against this narrative by comparing financial development in Southern Italy before and after Italian unification. Credit markets have always been weaker in the South than in the North since 1861 according to most indicators (Banca d’Italia 1990; Polsi Reference Polsi1993; A'Hearn Reference A'Hearn2000, Reference A'Hearn2005; SVIMEZ 2011, pp. 517–59). This was not, however, the sudden result of a financial colonisation that discriminated against Southern banking to the advantage of Northern finance. After the Restoration, the South, despite its great wealth (at least in comparison with the other Italian regions), had failed to develop a modern banking system. The predominance of public banking had put fiscal concerns above private credit. An absolute monarchy very close to Neapolitan interests and much less sensitive to those of the rest of the country had hindered widespread credit development. The result was a stagnating, regionally fragmented market where Sicily and the mainland were drifting apart and the needs of the provinces started to be timidly taken into consideration only in the late 1850s.Footnote 24

Such a system was ill-equipped to compete with the Piedmontese one. The Kingdom of Sardinia could not command financial resources comparable to those of the Two Sicilies (Chiaruttini Reference Chiaruttini2018, p. 3). However, the free hand left to private entrepreneurship and the proactive stance of a constitutional government gave rise to a dynamic banking system able to rapidly impose itself in a unified Italy. Crucial to its success was its ability to grow through integration rather than discrimination. The penetration of the National Bank into the South tolled the death knell for the Banks of Naples and Sicily as uncontested hegemons but heralded a new era in financial development. Competition led to a surge in total lending and easier access to credit across the whole South. The balance of financial power did shift northwards – the National Bank remained, after all, largely controlled by Northern shareholders – but the weaknesses inherited from Bourbon times and the lack of coordination between the Southern banks of issue mightily contributed to this shift. National integration resolved the two main problems of the South's banking system, namely regional fragmentation and crowding-out of private credit. But, in a comparative perspective, it downgraded its two largest credit institutions, leaving the appealing, albeit misleading, impression that Southern interests had been sacrificed in the effort to build a national market.