Women have historically been under-represented in politics. In most countries, women are a minority of elected legislators and appointed executive cabinet members, and only rarely become chief executives. There is, of course, variation in women's presence across countries, time and political office. Therefore, research seeks to identify the mechanisms that foster women's inclusion. One mechanism could be women political insiders who, in turn, bring other women into politics. Women may be more inclined to campaign on women's representation and value gender diversity than men; they may have networks that include more eligible women; or they may be less likely to employ gender stereotypes.

However, there are also reasons to suspect that women may not bring other women along. They may not have the political authority; they may worry about the appearance of bias if they do; and they may have the same gender biases or face similar constraints as their male counterparts when recruiting women. The empirical findings are mixed – several studies find that women (compared with men) gatekeepers are more likely to select women candidates for legislative office (Cheng and Tavits Reference Cheng and Tavits2011; Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2013; Verge Reference Verge2010). In the executive arena, some studies find that women chief executives, particularly presidents, appoint more women (Davis Reference Davis1997; Reyes-Housholder Reference Reyes-Housholder2016; Riccucci and Saidel Reference Riccucci and Saidel2001). Yet, others find that they do not, or do not necessarily (Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Barnes and O'Brien Reference Barnes and O'Brien2018; O'Brien et al. Reference O'Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015).

A potential explanation for the mixed findings is that women's and (men's) behaviour depends on the political contexts in which they operate. However, we know less about how distinct political contexts shape selectors’ preferences and behaviour. For example, in male-dominated environments, it may not be reasonable to expect women selectors to outpace men on women's inclusion, even if they preferred to do so. It is also plausible that there are environments in which men and women insiders have similar incentives to foster (or prefer) women's inclusion.

This article contributes to understanding how (a selector's) sex interacts with the political context. To do so, it relies on a longitudinal study of ministers’ political appointments in Spain and employs quantitative and qualitative methods to examine the if and why undergirding ministers’ behaviour. Why study ministers? Because most countries have never had a woman chief executive, studying ministers allows us to evaluate gender differences in additional countries. Furthermore, it builds on the growing literature on women's access to ministerial office (e.g. Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2016) to deepen our understanding of women in executive office.

Second, it sheds light on the characteristics of political appointees, an under-researched area. Data from OECD countries show that a large share of appointed officials change after a change of government, which suggests political relevance. In the overwhelming majority of OECD countries (75%), all or many advisers to the ministry's leadership change (OECD 2017: 144–145). In a smaller subset (26%), all or many of the most senior management also change. As in other political arenas, women tend to be underrepresented. In 2015, women held 32% of senior management positions in central governments in the OECD countries (2017: 96–97). Such senior management positions within ministries may be important for policy design and implementation because they form part of the chain of political delegation (Müller et al. Reference Müller, Bergman, Strøm, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2006). If gender diversity is indeed important for policy, we should analyse women's presence throughout the policy process. Women's presence in cabinet is often lauded because it may increase the substantive representation of women's interests. Yet, if women are only at the echelon of ministries and not involved throughout the policymaking processes, then there are solid reasons to question whether appointing women ministers is enough.

Empirically, this study examines ministers’ appointments in Spain during six governments between 1996 and 2018. It asks two questions: Do women (men) ministers bring more women along? And, why or why not? At the same time, it identifies the conditions under which women access appointed office. A longitudinal study of Spain holds several potentially significant variables constant – such as regime institutions and single-party governments – while homing in on the changes in the political context related to gender over time. Spain has evolved from having overwhelmingly male-dominated politics (and cabinets) to a significant female presence, including women holding diverse ministerial portfolios and some cabinets with gender parity. We can therefore examine (many) women and men ministers in distinctly gendered political contexts to identify preferences, incentives and constraints. Furthermore, Spain provides the leverage to analyse selectors’ behaviour because ministers make many political appointments that are important for policymaking. Methodologically, the study includes statistical analyses of a novel data set of political appointments made by 135 ministers and a qualitative analysis grounded in interviews with 30 ministers. This approach facilitates understanding of both whether selector sex matters for women's inclusion and how preferences, incentives and constraints shape ministers’ choices.

The statistical analyses show that women (or men) ministers did not appoint more women in their ministries at any time. Women's presence in subcabinet offices generally increased over time, though men remain over-represented, and the appointment of women is associated with the gendered nature of the ministry and women's presence in the political system. Instead of selector sex driving women's access to appointed executive office, in more gender-balanced political contexts, men and women ministers appointed more women. Moreover, the context changed, in part because critical political actors pushed for it. This imbued a new political sphere, subcabinet-appointed offices, with representational significance.

Selector sex and women's representation

The political recruitment approach (Norris and Lovenduski Reference Norris and Lovenduski1995; Randall Reference Randall1982) ‘suggests that in countries where women have made substantial inroads into politics, there may be a greater supply of potential female appointees. At the same time, women's presence may contribute to a breakdown of traditional gender norms’ (Krook and O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012: 843). This approach also suggests that women, either as individuals or as a group, may exercise influence over the selection and appointment of other women (Krook and O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012: 844).

Examining women as individuals, Catherine Reyes-Housholder (Reference Real-Dato and Rodríguez Teruel2016) hypothesizes that women presidents may bring more women along because of a perceived electoral mandate, gendered networks and homophily (the tendency of individuals to bond with others similar to themselves). Similarly, Melody Crowder-Meyer (Reference Crowder-Meyer2013) posits that gendered political networks and the recruitment of candidates like oneself may lead women to recruit more women legislative candidates in the US. Or, conversely, men's (‘old boy’) networks may be less likely to contain women (Verge Reference Verge2010).

However, other research casts doubt on this. Women may not value what women bring to the table or prioritize the advancement of women (or, not more so than men). As Cynthia Enloe (Reference Enloe1989: 6–7) states, ‘When a woman is let in by the men who control the political elite it usually is precisely because that woman has learned the lessons of masculinized political behaviour well enough not to threaten male political privilege.’ Evidence from Canada indicates that women (compared with men) gatekeepers do not value traits that are often associated with women, and women were not consistently more supportive of measures to advance women's representation (Tremblay and Pelletier Reference Tremblay and Pelletier2001).

Men and women (and/or subsets of them, such as women of colour or conservative men) may face different opportunities and constraints when they exercise political power. As Diana O'Brien et al. (Reference O'Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015: 710) conjecture regarding prime ministers’ appointment of cabinet ministers: ‘though male leaders can reap significant benefits from appointing women to their cabinets – and encounter costs for failing to do so – it is not clear that female leaders face the same incentives.’ In the masculine-coded arena of executive politics, the authors theorize that women may feel pressure to play by the existing gendered rules of the game, face accusations of favouritism if they promote women, and need to accommodate male power brokers in the party to assure their tenure in office. Governing parties may feel less pressure to appoint women if there is already a highly visible woman chief executive. Yet, given the cross-national quantitative nature of the study, the authors do not empirically determine incentives and constraints.

Empirically, several quantitative studies find correlations between women's presence in one political arena and another, though it is difficult to determine causality. Studies consistently show that women's participation in executive cabinets is highly correlated with women's presence within the political system, and particularly within legislative assemblies and the governing parties’ parliamentary groups (Claveria Reference Claveria2014; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2005; Reynolds Reference Reynolds1999; Siaroff Reference Siaroff2000; Studlar and Moncrief Reference Studlar and Moncrief1999). A study of the four highest ranks of government positions in 187 countries found an association between the presence of women in ministerial positions and at other ranks, though the authors were unable to use country-level data to determine the direction of the effect (Whitford et al. Reference Whitford, Wilkins and Ball2007). Several studies find that women are more likely to be selected to be candidates for legislative office where there is a woman gatekeeper – for example, in Canada (Cheng and Tavits Reference Cheng and Tavits2011) and the US (Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2013), and for local office in Catalonia, Spain, where there was a woman at the head of the candidate list (Verge Reference Verge2010).

However, in executive-appointed positions, the findings are mixed. Women presidents in Latin America appointed more women ministers (Reyes-Housholder Reference Reyes-Housholder2016). Women governors were more likely to appoint ‘white women’ in the US (Riccucci and Saidel Reference Riccucci and Saidel2001), and women prime ministers between 1968 and 1992 were slightly more likely than their male counterparts to have women in their cabinets in Western Europe (Davis Reference Davis1997). However, a study of 206 cabinets in 15 countries finds that a female prime minister or female-led coalition is associated with fewer female ministers, and that women leaders are no more likely than their male counterparts to appoint women to high-prestige portfolios (O'Brien et al. Reference O'Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015). Another study finds that the presence of a woman chief executive increases the odds of having a woman defence minister; however, the effect is driven by women who serve simultaneously as the chief executive and the defence minister (Barnes and O'Brien Reference Barnes and O'Brien2018). Hence, there is no bringing-women-along effect. Similarly, in a study of the appointment of ministers in presidential and parliamentary regimes, Clare Annesley et al. (Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019: 201) argue, ‘female selectors’ propensity to appoint other women to cabinet is not attributable to their sex, and not even the degree of their commitment to gender equality’.

Given the mixed findings, the question calls out for further research. This article investigates whether the political context within which men and women selectors operate matters. To understand if and how it matters, we need to examine empirically selectors’ preferences, incentives and constraints in distinct contexts.

Gender, cabinets and ministries in Spain

This study investigates whether women ministers appoint more women to subcabinet offices than men ministers, and the potential influence of the political contexts in which ministers make decisions. Spain is a useful country to analyse because the political context related to gender has changed over time, women have held many (diverse) ministerial portfolios, and ministers make many politically important appointments. Examining the period between 1996 and 2018, it takes a mixed methods approach.Footnote 1 First, it statistically tests whether selector sex matters for the appointment of women and the conditions under which women accessed appointed subcabinet office, based on a novel data set of the appointments of 135 ministers. Second, it provides a qualitative analysis of ministers’ preferences, incentives and constraints regarding political appointments, grounded in interviews with 30 former ministers. The interviews were semi-structured and focused on the process of making political appointments, the importance of subcabinet officials in the policy process, who influenced appointments and dismissals, and the criteria ministers used to select appointees.Footnote 2

This section describes women's presence in politics and then outlines the latter end of the chain of political delegation (Müller et al. Reference Müller, Bergman, Strøm, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2006) in Spain's parliamentary system, which includes subcabinet officials.

Women's descriptive representation

Spain has not yet had a woman prime minister or major party leader, suggesting persistent barriers. Nonetheless, it has evolved, in a short period of time, from having overwhelmingly male-dominated politics and cabinets to having a significant female presence. This study begins in 1996, when women's presence in parliament and cabinet surpassed 20%. Prior to this, women's representation in the lower chamber Congress of Deputies ranged between 5% (1979) and 15% (1993). Centrist Prime Minister (PM) Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo appointed the first woman minister (culture) in 1981. During the Socialist Party (PSOE) governments of PM Felipe González (1982–96), the percentage of women ministers ranged from none to a high of about 19%.

When this study begins, conservative PM José María Aznar (1996–2004) of the Popular Party (PP) appointed 28.6% women ministers to his first government in 1996 (see Table 1), which declined to 18.8% at the outset of his second government in 2000. Women held portfolios such as justice, agriculture, environment, health, science and technology, and foreign affairs. Concurrently, women's representation in the Congress of Deputies was 22% (1996) and 28% (2000). Yet, the PP group in the Congress of Deputies lagged far behind the PSOE's in women's representation, as did the party's executive committee. The share of women subcabinet officials, examined in this study, was only 13% during the first government and 19% during the second.

Table 1. Women's Representation in Spain (%)

Sources: Verge Mestre (Reference Mestre T2007); Government of Spain, various years; author's data.

Notes: aAuthor's calculation at the start of the government. bAuthor's data. Refers to appointments throughout the government's tenure. MP data refer to initial composition.

Socialist PM José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero appointed parity cabinets in 2004 and 2008. He was also the first PM to appoint a woman deputy PM (vicepresidenta del gobierno). All subsequent governments, to date, have had a women deputy PM. Women held portfolios such as development, equality, housing, defence, and economy and the treasury. Women's presence in Congress reached 36% in 2004 and 2008, again with women holding a larger share of seats for the PSOE than in the conservative PP. The PSOE executive committee also reached parity, while women's presence on the PP executive committee hovered near 30%.

Important for our analysis, in 2007, the Zapatero government passed its signature Equality Law. Among its provisions, it legally mandated sex-based candidate quotas for all parties and elections, which took effect for the 2008 elections. For the Congress of Deputies, the law stipulates that individuals of each sex should make up a minimum of 40% of the ballot list.Footnote 3 If a party fails to do so, its ballot will not be put to the voters. Notably, in the earlier 2004 election, the PSOE's parliamentary delegation had 46% women compared with 28% of the PP's. The law also established voluntary sex-based quotas for publicly traded companies and set targets for representation in the public sector, which includes the subcabinet positions examined here. However, the provisions for representation in the public sector were extremely weak. The law did not specify to which specific positions (e.g. ministers, secretaries of state, etc.) or institutions the rule applies, and there was no punishment for non-compliance. Nonetheless, it defined equitable presence as neither sex being less than 40%. The share of women subcabinet officials increased from 25.5% during the 2004–8 period to 34.6% during the 2008–11 period.

Under the subsequent conservative PP governments of PM Mariano Rajoy, women's presence in cabinet declined to 31% in 2011 and reached 39% at the start of his 2016 government. Women held portfolios such as the presidency, health, development, defence, and employment and social security. Women's presence in subcabinet positions declined slightly to about 31%. Women's presence in the Congress stayed steady at 36% in 2011 and increased to 39% in 2016, and the gap between the two major parties narrowed.

Chain of political delegation and ministers’ political teams

It is important to demonstrate that subcabinet officials are politically consequential, and therefore worthy of study, and that ministers have a degree of autonomy regarding whom they select. After all, if they had no autonomy, they would not be the selectors. The chain of political delegation runs from voters to parliamentarians, from parliament to the PM and government, from the PM to ministers, and from ministers to subcabinet officials.

The PM in Spain is very powerful institutionally (Heywood and Molina Reference Heywood, Molina, Peters, Rhodes and Wright2000) vis-à-vis parliament and the PM's party. To form a government, the Congress of Deputies votes only on the candidate for PM. The PM has the authority to appoint and dismiss ministers (and deputy PMs). Parliament can remove the entire government in a constructive vote of no confidence, which requires an absolute majority to simultaneously censure the sitting government and select a new PM, as in Germany. Consequently, ministers owe their positions directly to the PM.

In practice, the PM and the government are more important than the party organization when it comes to political appointments and policymaking while in office (Rodríguez Teruel Reference Rodríguez Teruel2011: 96–97). During this period, governments in Spain were single-party ones, and therefore interparty bargaining over portfolios and appointments did not occur. The cabinet includes the PM, deputy PMs (if any), and the ministers. Between 1996 and 2018, the number of ministers at the start of the government ranged between 13 and 17.Footnote 4 Ministers do not need to be parliamentarians and, in practice, often are not.

Once in office, ministers make many political appointments within their ministries. I focus on a subset of these appointments, which I term subcabinet offices. Subcabinet offices are filled through political appointments and the officials have a functional role in the ministerial hierarchy in altos cargos (high offices). This includes – from highest to lowest rank – secretaries of state, sub-secretaries (including general secretaries) and general directors (including technical general secretaries).Footnote 5 This study includes those offices that are part of the central state ministry located in Madrid.Footnote 6

Formally, ministers propose appointments to the full cabinet, which must then approve them. Interviews with former ministers indicate that they typically used their personal networks to generate referrals or directly identify candidates. Some consulted with the PM or deputy PM for suggestions, and others sought advice from ministers from previous governments. The ministers at times informally discussed their choices, particularly at the highest rank of secretary of state, with either the PM or the deputy PM of political affairs. Ministers only very rarely encountered resistance regarding individual appointees, and only rarely did a PM ask the minister to appoint a particular individual. Overwhelmingly, ministers thought they had substantial autonomy in appointments and dismissals.

The structure of each ministry varies, as does the number of subcabinet offices. Secretaries of state fall immediately below the minister in the ministerial hierarchy (Real-Dato and Rodríguez Teruel Reference Real-Dato and Rodríguez Teruel2016: 1). They report directly to the minister and are responsible for a policy area. There are no special legal requirements or limitations regarding who can serve as a secretary of state (Real-Dato and Rodríguez Teruel Reference Real-Dato and Rodríguez Teruel2016). While at a lower rank, general secretaries also tend to report directly to the minister and are responsible for a policy area. The law only stipulates that general secretaries be chosen from among those with management experience in the public or private sectors (Law 6/1997, Art. 16).

The other subcabinet offices are more technical, though they are filled through political appointments (Parrado Reference Parrado, Olmeda, Parrado and Colino2017: 88). Each ministry has a sub-secretary that directly reports to the minister and is responsible for managing the ministry. Ministers insisted that a good sub-secretary is essential for the functioning of the ministry, regarding policy design and implementation, advocating for the ministry's agenda, budgeting and spending, personnel and other matters. With a good sub-secretary, the ministry works; without one it stalls. Sub-secretaries are even more significant in ministries that do not have secretaries of state. The technical general secretary reports directly to the sub-secretary. General directors are responsible for a narrower policy area and typically report to a secretary of state, a secretary general or a sub-secretary.

Sub-secretaries, general directors and technical general secretaries must be chosen from among career civil servants of the central state, the regions or localities. They must have accreditation as ‘doctor, university graduate, engineer, architect or equivalent’ (Law 6/1977, Art. 15, 17, 18).Footnote 7 However, the law allows exceptions to the civil servant requirement for general directors, which governments use. Ministers also appoint a cabinet. This study only includes those with a rank of general director or above.

All of these subcabinet officers have management responsibilities, and they assist the minister throughout the policymaking and implementation processes. In interviews, ministers asserted that subcabinet officials, especially at higher ranks, are highly influential in the policy process. Ministers depend on their teams (which is the term ministers use) to transform broad ideas into concrete policies. Ministers also stressed the importance of the general committee of sub-secretaries and secretaries of state, known as the Consejillo (Little Cabinet). Chaired by the deputy PM, it meets prior to and prepares for the cabinet meeting (consejo de ministros).Footnote 8 While the Consejillo cannot formally make decisions for the cabinet (Parrado Reference Parrado, Olmeda, Parrado and Colino2017: 104), ministers note that, in practice, if the Consejillo reaches consensus on an agenda item, it is not normally debated extensively in cabinet. One minister quipped that the members of this committee ‘are the ones who are really in charge. To a certain point, they are more in charge than the government. Its role is very important.’Footnote 9 Another referred to the committee as the ‘heart of the government’, and yet another affirmed that if a ministry has a good representative on the Consejillo, that representative will fight for the minister and ministry. If not, a ministry's priorities may not make it onto the cabinet agenda.

Thus, ministers have a substantial degree of autonomy when they appoint their political team of subcabinet officials, who are important in the policy process in Spain.

Ministers’ sex and the appointment of women

Do women (or men) ministers appoint more women in Spain? This section presents the statistical evidence that they generally do not, and examines the conditions under which women accessed appointed office.

The analysis is based on a data set of ministers’ political appointments between 1996 and 2018.Footnote 10 I reconstructed the ministries’ structures and changes to determine the relevant subcabinet offices, and then collected the appointment information from the official state bulletin.Footnote 11 The unit of analysis is an appointed minister during a single tenure. For example, an individual minister who was appointed twice is two appointed ministers. A minister's tenure starts with the official appointment to a particular ministry and ends when the individual is officially dismissed from that same ministry or at the end of the government. The data set includes 135 appointed ministers, 47 (34.8%) women and 88 men.Footnote 12 There were no visible minorities among the ministers studied. While I refer to men and women for the sake of brevity, they are white men and women. Consequently, I cannot assess the effect of distinct intersections of race/ethnicity and sex.

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics about the ministers and subcabinet officials by government and overall. Women subcabinet officials is the percentage of women in subcabinet positions at the start of the minister's tenure. It is a snapshot measured at two months after the ministers’ official appointment.Footnote 13 This is an inductively derived cut-off, the time by which ministers have typically appointed their teams. Women senior cabinet officials is the percentage of women in subcabinet positions above the rank of general director. While general directors are political appointees, they are the least senior and must be civil servants, unless a policy exception is made. Each is used as a dependent variable in the statistical analyses. Between 1996 and 2018, women were 25.9% of subcabinet officials and 25.2% of senior subcabinet officials. In general women's presence in subcabinet office increased over time until 2011, when it levelled off. In particular, women's representation increased during the Zapatero governments, reaching nearly 35% in his second government, though it did not reach the parity that existed in the cabinet.

Table 2. Women in Executive Offices, Spain

Notes: *p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01. Refers to change from previous government. Outset: measured at the beginning of a new government.

Figure 1 presents the data on women subcabinet officials according to the sex of the minister for the entire period of study and for each government.Footnote 14 Men appointed women to 24.5% of the subcabinet positions, compared with 28.6% for women ministers. The shares are similar for senior subcabinet officials. The largest gap in the descriptive statistics occurs during the first Rajoy government, when women ministers appointed 39% women subcabinet officials compared with 28% for male ministers. Using ANOVA tests, there is no statistically significant difference (p < 0.10) between male and female ministers during any of the time periods.

Figure 1. Ministers’ Sex and Women Subcabinet Appointees, Spain, 1996–2018

Notes: In percentages. ANOVA tests showed no statistically significant differences (p < 0.10) between male and female ministers at any time.

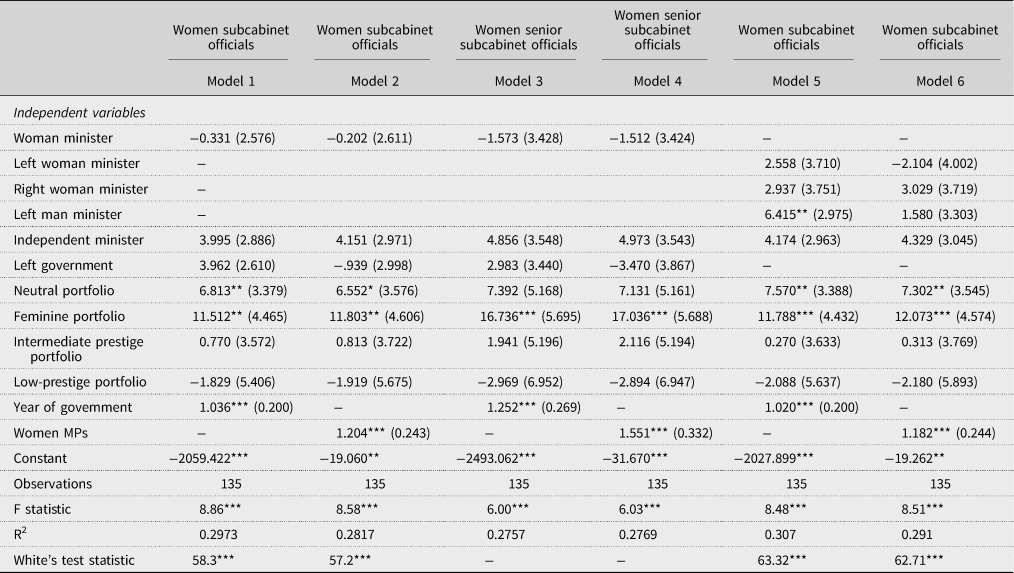

To further evaluate the relationship between the sex of the minister and political appointments and the conditions under which women access appointed office, I estimate linear regression models. The sex of the minister is the independent variable, measured using a dummy variable (woman minister = 1). The dependent variable is the percentage of women subcabinet officials (models 1 and 2), or the percentage of women senior subcabinet officials (models 3 and 4).

The models include a series of controls based on hypotheses in the literature on the appointment of women ministers. Much of the extant literature finds that left-wing governments appoint more women (Caul Reference Caul1999; Moon and Fountain Reference Moon and Fountain1997; Reynolds Reference Reynolds1999; Siaroff Reference Siaroff2000). I therefore include a dummy variable for left government (left = 1). Men are more likely to lead ministries associated with masculinity and those with higher prestige (Claveria Reference Claveria2014; Krook and O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012). I hypothesize that the same patterns hold for subcabinet offices, and control for the prestige and gendered nature of the ministry. To do so, I code Spain's ministries following the categorization of Mona Lena Krook and Diana O'Brien (Reference Krook and O'Brien2012). Ministries are coded as high-prestige portfolio (e.g. foreign affairs), intermediate-prestige portfolio (e.g. education) or low-prestige portfolio (e.g. culture). I also code them as masculine portfolio (e.g. foreign affairs), neutral portfolio (e.g. housing) or feminine portfolio (e.g. education). Because of the three-fold categorization of the gendered nature and prestige of the portfolio, I leave masculine portfolio and high-prestige portfolio out of the models. They are therefore reference categories.Footnote 15

Specialist (compared with generalist) recruitment patterns are also associated with the appointment of women ministers (Claveria Reference Claveria2014; Krook and O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012). Specialist ministers may have larger networks from which to recruit subcabinet officials in the relevant policy area and therefore foster women's representation. Thus, I include a dummy variable for independent minister (independent = 1), because independents are more likely to be tapped for their policy expertise in Spain.Footnote 16

Existing studies also control for time and the percentage of women in the legislature (O'Brien et al. Reference O'Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015; Reyes-Housholder Reference Reyes-Housholder2016). The logic underlying the former is that women's representation may increase with time, perhaps due to modernization or contagion processes. As an indicator, I use the year of government formation. The percentage of women in parliament is often used as an indicator of the supply of women from which to recruit or of the openness of the political system to women. I use the percentage of women MPs in the Congress of Deputies. However, these variables are highly correlated (r = 0.902). I therefore estimate alternative models that include one at a time.Footnote 17 Ideally, we would also control for the implementation of the Equality Law. However, because of collinearity with the year of government (and women MPs) variable, I estimate separate models. White's test shows evidence of heteroscedasticity in models 1 and 2. The results for these models therefore include robust standard errors.Footnote 18

The results in Table 3 show that there is no statistically significant difference in the appointment of women based on the sex of the minister in any of the models. Women ministers did not appoint more women than men ministers.Footnote 19 Turning to the control variables, the coefficient for independent minister is positive but not statistically significant. Contrary to expectations, the coefficient for left government is not significant. This may be because the models control for time (contagion).Footnote 20 Tània Verge (Reference Verge2015) argues that advances in women's parliamentary representation in the PSOE pushed the PP to do the same, as part of party competition in the two-party dominated system. In models 1 and 3, the coefficient for the year of government is positive, and the results are highly significant (p = 0.000), showing that women's representation increased over time. The same is true of the percentage of women MPs in models 2 and 4. I estimated the same models adding the control for the implementation of the Equality Law, which was non-significant. When the Equality Law control replaces the year of government variable (or women MPs), there were on average 14 percentage points more women subcabinet officials when the law was in place than when it was not (p = 0.000).Footnote 21

Table 3. Linear Regression Results, All Governments, Spain, 1996–2018

Notes: *p < 0.10; **p = < 0.05; ***p < 0.01. Standard errors in parentheses. The standard errors are robust for models 1, 2, 5 and 6.

Consistent with studies of the appointment of ministers, feminine portfolio is associated with the appointment of women subcabinet officials compared with masculine portfolios (the reference category), and the difference is statistically significant across the four models. Gender neutral portfolios have more women subcabinet officials than masculine ones, though the difference is only statistically significant at the < 0.05 level in model 1. Turning to the prestige of the ministry, the coefficients for intermediate prestige and low-prestige portfolios (compared with high-prestige portfolios) are not statistically significant. Therefore, it appears to be the gendered nature of the portfolio that is associated with women's representation in subcabinet offices and not the portfolio's prestige.

The results for all women subcabinet officials and women senior subcabinet officials are similar. Even where ministers faced fewer legal constraints on their appointments (senior officials), there were no differences based on the minister's sex. However, there is a notable difference with regard to the gendered nature of the portfolio. Compared with the reference category of masculine portfolios, feminine portfolios are associated with an 11–12 percentage point higher share of women subcabinet officials. That increases to 16–17 points for women senior subcabinet officials.

Additionally, I examined each government, the governments of each PM, and right and left governments separately. There were no statistically significant differences between women and men ministers at any time. To test for the interaction of the minister's sex and the type of portfolio, I ran models with a three-category variable for the gendered nature of the portfolio and the prestige of the portfolio and introduced interaction terms with each and woman minister (not shown). There are no statistically significant interactions when all women subcabinet officials is the dependent variable, suggesting women ministers do not behave differently from men. However, calculating the marginal effects revealed that women ministers in feminine portfolios appoint more women subcabinet officials than women in masculine portfolios, while men ministers do not behave differently across masculine and feminine portfolios.Footnote 22 Models with women senior subcabinet officials as the dependent variable suggest one difference between female and male ministers: women ministers in feminine portfolios appointed more women to senior subcabinet positions than men ministers in feminine portfolios.Footnote 23

The statistical analyses thus far provide little evidence that women appoint more women. However, descriptive statistics suggest that men in right-wing governments may bring fewer women along. Using the indicator for the appointment of all women subcabinet officials, men in left governments (N = 30) appointed 31.1% women, women in left governments (N = 30) appointed 29.9%, women in right governments (N = 21) appointed 27% women, and men in right governments (N = 58) appointed 21%. The 10-point difference between left and right men is statistically significant at the < 0.01 confidence level.Footnote 24 I therefore estimated alternative linear regression models that include dummy variables for left woman minister, right woman minister and left man minister. Right man minister is the excluded and therefore reference category. White's test shows evidence of heteroscedasticity; the results therefore include robust standard errors. In model 5, the coefficient for left man minister is positive and statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level. Left men ministers are associated with 6 percentage points more women subcabinet officials than right men ministers. However, caution is necessary; model 6 does not show significant effects.Footnote 25

Political contexts and the appointment of women

While women ministers, as individuals, did not appoint more women than their male counterparts, women's presence and actions, more broadly, were important. This section examines ministers’ preferences and incentives, the changing (gendered) political context and barriers to women's representation. It highlights the key role of critical actors who incentivized men and women ministers to appoint more women. It also argues that distinctly gendered contexts stymied or helped advance women's representation in subcabinet office. Finally, it stresses that political action can transform political spaces, imbuing them with representational significance, which occurred with appointed ministerial teams.

The analysis draws on 30 interviews with ministers from the conservative PP governments of PM Aznar (1996–2004) and PM Mariano Rajoy (2011–18), and the socialist governments of PM Zapatero (2004–11). The interviews included 13 PP ministers and 17 PSOE ministers (17 men and 13 women).Footnote 26

Ministers’ preferences and incentives

When questioned about the characteristics they considered when making political appointments, overwhelmingly, ministers indicated that they valued substantive and policy area expertise, management skills, and personal and political trust. Ministers varied in the degree to which they valued political skills. Political skills tended to be more valued in higher-ranked officials, such as secretaries of state, and their importance depended on the political skill set of the minister.

While ministers did not appoint individuals that represented other parties, party membership in the governing party was not consistently important. In the higher-level offices, ministers sought out individuals who at a minimum supported the party programme and/or were ideologically proximate. Yet, party affiliation was less important at lower levels of the ministerial hierarchy, and several ministers indicated that they did not seek out information about the party sympathies or affiliations of directors general. Ministers overwhelmingly reported that the governing party's organization had little to no influence on their appointments.

When asked about representational criteria (Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019), no ministers, of either party, referred to the representation of ethnic, racial or sexual minorities. Overwhelmingly, ministers referred to territorial considerations in the nomination of ministers but not in appointments within ministries.Footnote 27 There was a clear discrepancy by party with regard to gender. PSOE ministers, women and men, frequently referred to gender equality considerations, which was nearly absent among the PP ministers.

Fifteen of the 17 PSOE ministers interviewed noted that the PM or deputy PM for political affairs (Fernández de la Vega) emphasized that they should work towards gender equality in appointments. One Socialist minister said that the only instructions he received about forming his team, ‘which was a pleasure to fulfil’, was about gender equality. Some PSOE ministers stated that the appointment of women was an aspiration or recommendation, while others said it was a ‘directive’. According to another minister, ‘if anyone had brought four proposals for secretary of state that were all men, it would probably have generated a debate in the cabinet and I think it wouldn't have been approved’. The PM told one minister to appoint a specific woman to secretary of state because he did not have enough women on his team, which he accepted because he agreed with the goal.Footnote 28

Some ministers shared the government's commitment and referenced their personal support of gender equality. Others referred to its importance to the PM or the government as a whole. One minister explained that there was no explicit opposition within the government to advancing women's representation because it was a ‘leitmotif’ of the Zapatero governments. Ministers highlighted that not every minister equally believed in or advocated for women's inclusion. Several ministers of both sexes referred to themselves as feminists and pointed out that not all of the women (or men) ministers were feminists. However, they also noted that if anyone opposed PM Zapatero's gender equality policies and measures to foster women's representation, they would not have said so. Therefore, the evidence indicates that advances in gender equality during the Zapatero governments were a result, in part, of incentives that existed for men and women.

In contrast, none of the 13 PP ministers interviewed stated that they received instructions regarding women's representation in subcabinet offices from the party, the PM or the government generally. One (male) minister, unprompted, stated that appointing women was important to him personally, which manifested in his appointments.

The gendered political contexts

Incentives from above to appoint women clearly differed across parties. Additionally, the political context in which ministers operated changed with time, in particular the gender (im)balance in the political institutions and the centrality of women's equality as a political issue. Yet the context changed, in part because of purposive political action to advance gender equality, including in subcabinet offices.

As discussed previously, women's representation in Spain was meagre when democracy was re-established in 1977. By 1986, women were only 6.3% of the MPs in the Congress. In 1988, pushed by feminists in the party (Threlfall Reference Threlfall2007), the PSOE introduced party-level quotas that required a minimum of 25% women on candidate lists for elected and internal party offices. The party strengthened the quota in 1997, requiring that neither sex hold less than 40% of internal and public offices (Verge Mestre Reference Mestre T2007: 169–174). Advances of women's representation in the PSOE's parliamentary group account for a large share of the increased presence of women in parliament – but not all of it. Competitive pressures in the two-party dominant system pushed the PP also to advance women's representation, but without party quotas (Verge Reference Verge2015). Nonetheless, the PP lagged behind.

When the PP governed in 1996, for the first time there was no explicit party or governmental commitment to advance women's representation in subcabinet office. Additionally, interviews and the descriptive statistics (see Table 1) indicate that there were few women from the party to appoint. Women were 14% of the party's MPs and 12% of its executive committee. And women were 13.4% (1996–2000) and 19.0% (2000–4) of subcabinet officials. There were some advances in women's presence. PM Aznar appointed more women ministers in 1996 (28.6%) than his predecessor (16.7%) and backed the selection of women as speakers of the Congress of Deputies and Senate for the first time.

In contrast, there were strong and explicit party and governmental goals to advance women's representation during the leftist Zapatero governments (2004–11), including in subcabinet offices. Aided by the party's earlier advances in gender equality, it created similar, strong incentives for women and men ministers to appoint women in their ministries. The PSOE and PM Zapatero placed women's empowerment at the centre of the election campaigns and governing actions. The party's 2004 election manifesto included pledges of a cabinet with gender parity, the development of a quota law for elections, and advances in the representation of women in the public administration, among other provisions (PSOE 2004). When the Zapatero government took office, women were more than 45% of the PSOE executive committee and of its parliamentary group.

In his first government (2004–8), in addition to appointing a parity cabinet and a woman deputy PM, PM Zapatero created a general secretariat of equality policy in the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, which was the first post in the area of equality. The minister appointed a well-known feminist sociologist, Soledad Murillo, to head it. The government passed a series of laws related to gender. Murillo and the ministry designed the government's Equality Law, which, along with other policies, ‘put Spain at the vanguard of gender equality policymaking in the European Union’ (Valiente Reference Valiente and Field2013: 177). As discussed previously, it legally mandated sex-based candidate quotas for all elections. It also set targets for women's representation in the public sector, which includes the subcabinet offices examined here. The provisions were weak, but the law moved the consideration of gender beyond the legislative and party arenas and flagged that (women's) representation was important in appointed offices. Article 52 states that the government will heed to the principle of the equitable representation of men and women in management bodies in the state administration and public organizations dependent upon them, and defined equitable presence as no sex being less than 40%. At the outset of his second government, PM Zapatero created a Ministry of Equality, and appointed Bibiana Aído to lead it, though she was not well-known in gender policy circles or a party heavyweight (Valiente Reference Valiente and Field2013: 184). Following the Equality Law, women's presence in subcabinet offices increased 9 percentage points, from 25.5% (2004–8)% to 34.6% (2008–11), though short of the level of women's representation in the PSOE's executive committee, parliamentary group and the cabinet.

In interviews, ministers stressed that the PSOE's internal party rules and party culture, developed over decades of gender equality advances, muted potential opposition to (also see Franceschet and Thomas Reference Franceschet and Thomas2015) and created additional incentives to support further gender equality measures – this time related to political appointments. Ministers recognized that there were disagreements within the party; nonetheless, they emphasized that the party had made a decision to ‘bet on equality’. This made it costly to manifest resistance openly. According to one minister, ‘you know that you need to choose a team where there are women, where there are men, and this, little by little, is inserted into the political culture of the party’. Another minister noted that advances in equality in the government went along with the evolution of the party, which consolidated during the Zapatero governments.

During the conservative governments of Mariano Rajoy (2011–18), women's presence in cabinet decreased compared to the previous Zapatero governments, though it was higher than under the conservative governments of PM Aznar. However, women's presence in subcabinet offices remained relatively constant (at about 31%). The ministers interviewed confirmed that there were no explicit instructions from the prime minister or anyone else to appoint women. When prompted about possible gender considerations, one minister affirmed that women's presence in the party came about ‘organically’ – stressing that the PP is not a ‘party of quotas’ or of ‘gestures’, emphasizing that individuals are appointed based on their skills. However, what might appear to be organic may not be. By 2011, the PP was a very different party organization from what it was when it last governed. While still lagging behind the PSOE, the PP had experienced a great degree of feminization, triggered in part by electoral and legal pressures. Women's presence on the party executive committee surpassed a third and hovered near 40% of the parliamentary group.

As had occurred with advances of women's representation in parliament, flagging gender equality considerations for political appointments during the Zapatero governments also appears to have imbued a new political sphere with representational significance. When the PSOE government of PM Pedro Sánchez took power in 2018, with a 65% majority women cabinet, Spanish newspapers reported on the gender composition of subcabinet political appointments, including the headlines: ‘Masculine dominance in Sánchez's inner circle and parity just barely in secondary levels’ (Romero Reference Romero2018) and ‘All the president's men: Sánchez's hard core in Moncloa [executive palace] suspends in parity’ (Castro Reference Castro2018), notably extending gender considerations to the PM's inner circle.

Falling short of sex-based equality in appointments in a favourable context

Even in the favourable context of the Zapatero governments, ministers fell short of parity in their appointments and of the minimum 40% target of the Equality Law. The interviews suggest several reasons.

The incentives were not fully consistent. The emphasis on gender equality varied by ministry. The minister of defence recognized that the expectation of gender equality was not as strong for her ministry as it was for others. While ministers noted that there was an attempt at equality in the ministries, it was also considered across the government. If one minister appointed several men, the next needed to appoint more women. In particular, one of the aspirations was that the Consejillo would have gender parity, as the cabinet did, though this was not achieved.

There were implementation challenges. Some highlighted the masculine nature of some ministries, which made it difficult to find women. For example, a minister noted that there were few women in the echelon of or with knowledge of the armed forces. However, other ministers questioned that qualified women could not be found, or that distinctly qualified men were appointed to such positions. One minister stated: ‘If you don't ask for women's CVs, you don't get women's CVs, even if they are equally as good or better than other professionals whose CVs do make it to you.’ In other words, ‘There has to be the will to incorporate and find them.’ Another minister frankly noted that appointing a woman could cause a backlash in certain areas: ‘If you are going to appoint a woman general director of the police, you have to think twice.’

There were also monitoring challenges. Ministries periodically submitted data on the sex composition of their ministries. However, appointments are not all made simultaneously. Some ministers start at the beginning of the government's tenure, while others come in with a reshuffle. Subcabinet officials are also, at times, replaced individually. The Gender Equality Law (2007) did not establish a quota for political appointments that was specific to each rank and did not sanction non-compliance, in contrast to the election list quotas. Furthermore, the equality minister, after 2008, monitored but could not impose gender parity on other ministers. Subsequently, the Ministry of Equality was disbanded and its responsibilities transferred to a secretariat of state in 2010, in response to the Great Recession. Also, some ministers noted that secretaries of state and general secretaries influenced appointments in their functional areas because general directors would be under their direct supervision. Ministers did not always closely monitor these suggestions for their equality implications.

Conclusion

This study finds little evidence that women ministers, as individuals, appointed more women than men ministers in Spain. This precise finding is not meant to be generalizable to distinct contexts because the larger takeaway is that political contexts matter. We therefore should not expect to find, consistently, that women insiders behave differently from men. It provides evidence that incentives to appoint a more gender-balanced team and more gender-balanced political contexts can lead both women and men to bring more women along.

This study suggests additional lessons. The first is that political actions can transform political spheres and give them representational significance. This is in line with much of the literature on women's representation. Yet, we should also consider the degree to which environments are resistant to representational claims. The link between representation and elected legislatures is clear. That representational link is comparatively less obvious conceptually and less visible in practice when it comes to political appointees. Nonetheless, political action in Spain brought (gender) representational qualities to subcabinet appointments. Further demonstrating the importance of political action, while there has been significant, persistent political action to advance gender equality in Spain, the same has not occurred in this increasingly diverse country with regard to the representation of ethnic or racial minorities, in legislative or executive offices. And there are hardly any minority representatives in office (Vintila and Morales Reference Vintila and Morales2018).

Second, it provides further evidence that election mandates for public commitments to advancing women's presence in office matter (Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Reyes-Housholder Reference Reyes-Housholder2016). In this study, the PSOE, led by a male PM, made a public commitment to advance women's political equality. Third, it finds that selectors’ incentives matter (O'Brien et al. Reference O'Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015). Men and women can indeed face distinct incentives in different environments. This article shows that critical political actors can create (or not) incentives for men and women to advance women's representation. Socialist PM Zapatero and the PSOE sent a strong message to ministers to advance women's representation, and political institutions reinforced the incentives. Spain's powerful office of the PM and single-party governments aided the inclusion of women, when the PM prioritized it. Institutionally weaker PMs or those who need to bargain across parties could see their directives sidestepped or watered down. Nonetheless, the analysis also suggests that over the longer term incentives can become norms.

Supplementary information

To view the supplementary information for this article, please see https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2020.10.

Acknowledgements

I thank the ministers who generously agreed to be interviewed, and Anamaria Ballesteros, Patricia Puig and Lourdes Solana for research assistance. I gratefully acknowledge funding from Spain's Hispanex Program, the American Political Science Association, the Valente Center for Arts and Sciences, and Bentley University. For diverse reasons, thanks to Kristin Anderson, Louise Davidson-Schmich, Susan Franceschet, Jeff Gulati, Alison Johnston (especially), Irene Martín, Diana Z. O'Brien, Jennifer Piscopo, Charles Powell, Juan Rodríguez Teruel, Tània Verge, Georgina Waylen, and the thoughtful anonymous reviewers.