Introduction

The creation of Canadian Medicare almost 50 years ago, and the British National Health Service almost 70 years ago, makes 2018 an opportune moment to reflect upon where we have been, where we are heading and the role of nurses as change agents for better health care tomorrow. The purpose of this paper is to consider the role of history as a reference point for evaluating nursing policy today and future foci for change. First, it takes some radical ideas put forward for reform in the run-up to the National Health Service (NHS), and suggests these merit revisiting in reviewing the policy position of nursing and the prospects for nurses delivering a better future for health care. Second, it considers whether the policy trajectory set at the inception of the NHS has had an enduring influence on nurses’ capacity to influence policy within the NHS. It presents evidence on the current strength of education and the nursing workforce within England. Finally, it proposes the current policy trajectory needs a reset, since policy has failed to keep pace with many EU and Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries in medical workforce planning. Building a better educated workforce with the cognitive capability and know-how to make effective, evidence-based decisions delivers better health outcomes for patients, families and populations (Aiken et al., Reference Aiken, Sloane, Bruyneel, Van den Heede, Griffiths, Busse, Diomidous, Kinnunen, Kozka, Lesaffre, McHugh, Moreno-Casbas, Rafferty, Schwendimann, Tishelman, van Achterberg and Sermeus2014). The current policy turn in England to train an associate nurse as a second level nurse, moreover, runs counter to the evidence and (Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Ball, Murrells, Jones and Rafferty2016) and is therefore unlikely to succeed. Nurses need to be engaged in the design as well as the delivery of policy at every level in order in order to optimise their contribution to a better future for health care.

Nursing and the early NHS

Nursing is the largest workforce in health care, yet the nursing voice in policy-making has historically been weak. In the run-up to the NHS negotiations, the drama focused on getting the doctors on board (Webster, Reference Webster1998; Klein, Reference Klein2013) famously by ‘stuffing their mouths with gold’. In contrast, nursing was given scant attention in the negotiations which followed, the assumption being that nursing would adapt to whatever planning arrangements were made for it, not that it would contribute to the architecture of those arrangements (Dingwall et al., Reference Dingwall, Rafferty and Webster1988). Nursing entered the NHS in a state of crisis. The shortage of nurses after the Second World War was described by Aneurin Bevan, Minister of Health, as approaching a ‘national disaster’ (Rafferty, Reference Rafferty1996). Despite this, the rhetoric of crisis failed to translate into the participation of nursing in NHS advisory and policy-making machinery. In a speech to the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) Bevan was evasive on the question of consultation on policy matters, and was subjected to little external pressure from the RCN for greater nurse representation, in marked contrast to the assertiveness of the British Medical Association (BMA) leadership (Rafferty, Reference Rafferty1996).

The wartime emergency had revealed the scale of the workforce shortage and created an ‘enrolled nurse’ as a second level nurse in 1943, to supplement and support the registered nurse (RN). The establishment of the NHS with the anticipated expansion in facilities and demand for labour highlighted the need for a comprehensive review of the nursing position, and a Working Party on Nurse Recruitment and Training, under the chairmanship of Sir Robert Wood, was appointed in January 1946 (Ministry of Health et al., 1948). The task of the Working Party was to assess the nursing force required for the future health service and make recommendations as to how such a force could best be recruited, trained and deployed. But the deliberations of the Working Party proved divisive, splitting opinion between radical and moderate camps, on both the diagnosis of the ills of the situation and the remedies required to solve it. John Cohen, Secretary to the Working Party, broke from the main committee and produced his Minority Report which reflected his training as a psychologist deploying the language and methods of industrial psychology (Rafferty, Reference Rafferty1996). He argued that tackling the human relations aspects of hospitals and care processes was crucial to improving morale, boosting productivity and outcomes for nurses as well as patients. Cohen was one of the first to measure nursing care by using length of stay as an outcome measure of clinical effectiveness (Rafferty, Reference Rafferty1996) and to advocate the empirical study of the linkage between patient outcomes with skill mix. Many other of Cohen’s recommendations also appeared ahead of their time, asserting that training effectiveness and retention could be improved by enriching training and reshaping the division of labour. This bore the imprimatur of scientific management and the ‘efficiency movement’, which had infiltrated American and Canadian nursing before it had British nursing (Reverby, Reference Reverby1981; McPherson, Reference McPherson2003). Cohen’s cri de coeur was that nursing services needed radical treatment instead of ‘first aid’, and a scientific analysis of nursing work, in order to align the proper role of the nurse with the needs of a comprehensively planned health service (Rafferty, Reference Rafferty1996). He argued that improving human relations in hospital would have a similar effect by enhancing productivity as it had in factories, and by enriching training there would be a concomitant improvement in training effectiveness and retention of staff. Lack of attention to long-term planning, he contended, threatened to leave nursing and other services built upon inadequate foundations. Poor quality data were perceived as the major impediment to long-term reconstruction of nursing services, and statistical resources were condemned as ‘lamentably defective’ (Rafferty, Reference Rafferty1996: 171). Both Majority and Minority reports drew on social scientific methods of analysis, specifically job analysis and recommended methods of streamlining the nursing division of labour by reducing the training period from three to two years. The Minority Report in particular was highly critical of the inadequate supply of data on which to base central planning.

Nursing exposed the weaknesses and fragility of the NHS planning apparatus. Statistical sources within the Ministry of Health were described by Cohen as pre-scientific, and nursing was used by Cohen to illustrate the flawed edifice of government policy-making. Shortages threatened the viability of the new service. Yet the crisis did not translate into a policy shift nor in nursing organisations pressing for change (Rafferty, Reference Rafferty1992). It was not exploited by nurse leaders into political capital to attract the resources necessary to provide a high quality service and long-term career. Rather, the history of the early NHS reveals that the traditional relationship between service and education remained intact in which long-term goals were sacrificed to short-term expediency (Rafferty, Reference Rafferty1996: 181).

Significantly, it was a Canadian nurse, midwife and health visitor, Gladys Beatrice Carter, a graduate in economics who produced a radical critique of, and alternative to, the status quo. Carter was one of a tiny minority of graduates in nursing at the time, an intellectual firebrand whose prose bears the hallmarks of a political pamphleteer inciting her readers to rise up and rebel. In her ‘New Deal for Nurses’, published in 1939, Carter produced one of the most trenchant analyses of nursing education, citing the cortege of official and semi-official committees throughout the 1930s which had opened the debate to publicise and improve conditions for nurses, yet failed to effect change (Carter, Reference Carter1939). Drawing on Roosevelt rhetoric, Carter’s manifesto mapped out a blueprint for reform including grants-in-aid to hospital; separating service from education and upgrading nursing education to better align with public health needs. These proposals demonstrated how in tune she was to the environmental forces and social dynamics that shape health in its broadest sense, including the health of nurses themselves. She argued that it was the conditions under which nurses were trained and educated, worked and had to pursue a living and their career opportunities which prevented them functioning to their full potential. It was not until some 20 years later that Carter would find the opportunity to put some of her ideas into practice and secure a platform to translate her view that a well educated workforce was an essential precondition for being effective as a nurse and delivering comprehensive care, an ambition which lay at the heart of the new NHS.

Carter is a shadowy character whose contribution to nursing history bears further scrutiny. Little is known of her activities in the intervening period but she resurfaces in the late 1950s when she arrived at the University of Edinburgh as a Boots Fellow in Nursing Research in 1959 (Weir, Reference Weir1996). Taking up the cause of university education for nurses, her relevance lies in her presentation of evidence to the university committees considering the case for establishing an undergraduate degree for nurses at Edinburgh in the 1960s. This drew on her knowledge and experience of Canadian experiments including that at the University of Toronto (Palmer, Reference Palmer2013). Her evidence confirms the benefits of investment in nurse education for public and population health. This was not accidental but strategic in the sense that the Rockefeller Foundation had strong interests in public health and it was its public health agenda which had spearheaded investment in its programme in the University of Toronto, the United States and across Europe (Rafferty, Reference Rafferty1995; Lapeyre, Reference Lapeyre2015). In Toronto, the programme in public health nursing was led by its charismatic leader, Kathleen Russel, herself a beneficiary of a Rockefeller Fellowship. It was also the Rockefeller Foundation which was being courted as the potential funder for the Edinburgh initiative.

The relationship with Rockefeller was nurtured by Professor Francis Crew, a man of expansive vision and interests in science and public health. Not surprisingly the Edinburgh course bore the imprimatur of its community medicine and public health origins; as students were dual trained both in acute and community nursing with the result that working in the community became the preferred destination of the Edinburgh graduates in follow-up studies of the early cohorts (Weir, Reference Weir1996). Graduates seemed to value the autonomy they experienced in the community where they could use their initiative, exercise their discretion, judgement and critical thinking in decision-making, rather than feeling hemmed in by the hospital. Carter’s own research into the numbers of graduates within the profession, and the need to educate the next generation of nurse tutors to graduate level, was also an important ingredient in crafting the case for change, though full graduate status for the profession had to wait almost 60 years. Both Cohen and Carter’s critiques were radical but remained marginal to the policy agenda which emerged in nursing and the NHS. But they anticipated research and policy changes which were to surface some 60 years later.

Fast forward to 2017 and much appears to have changed in the NHS; the entry level into practice is set at degree level; nurses have prescribing rights; advanced practice nurses are in the forefront of chronic disease management and expanding access to services, safely, with positive outcomes for patients and often more cheaply than doctors (Maier and Aiken, Reference Maier and Aiken2016). Nurses are running primary care practices, employing general practitioners, leading and shaping new models of care. Many of these changes have been led by nurses and deliver better outcomes for patients (WHO, 2015). Cohen’s contention on linkages between the nursing workforce and length of stay now has an evidence base in which better nurse staffing levels are associated with a series of organisational as well as patient outcomes including lower length of stay (Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Ball, Drennan, Jones, Reccio-Saucedo and Simon2014; Aiken et al., Reference Aiken, Sloane, Rafferty, Bruyneel, McHugh, Maier, Moreno-Casbas, Ball, Ausserhofer and Sermeus2017; McHugh et al., Reference McHugh, Rochman, Sloane, Berg, Mancini, Nadkarni, Merchant and Aiken2016). Cohen’s call for a scientific analysis of nursing work has yielded many excellent studies, some of the cross-national accounts linking more and better skilled nurses in acute care to better outcomes for patients and improved responses to patients needing life-saving interventions (Kane et al., Reference Kane, Shamliyan, Mueller, Duval and Wilt2007; Tourangeau et al., Reference Tourangeau, Doran, McGillis Hall, O’Brien Pallas, Pringle, Tu and Cranley2007; Shekelle, Reference Shekelle2013; Aiken et al., Reference Aiken, Sloane, Bruyneel, Van den Heede, Griffiths, Busse, Diomidous, Kinnunen, Kozka, Lesaffre, McHugh, Moreno-Casbas, Rafferty, Schwendimann, Tishelman, van Achterberg and Sermeus2014; Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Ball, Drennan, Jones, Reccio-Saucedo and Simon2014; West et al., Reference West, Barron, Harrison, Rafferty, Rowan and Sanderson2014; Neuraz et al., Reference Neuraz, Guerin, Payet, Polazzi, Aubrun, Dailler, Lehot, Piriou, Neidecker, Rimmele, Schott and Duclos2015).

Compared to the devolved countries within the United Kingdom, Europe and high income countries such as Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand, England has been comparatively late in embracing degree entry into practice in 2013. As a result, the number of graduates in the workforce in England remains one of the lowest in Europe, with an average of 28%, compared to 100%, even in countries such as Poland and Spain which have been significantly hit by austerity measures. This reluctance of England to embrace graduate entry has important antecedents: 7% of nurses held matriculation equivalence in 1948 at the outset of the NHS. Not until the 1960s was there any attempt to establish a university degree-based programme for nurses. While there had been post qualification diploma courses for nurses during the inter-war period (Brooks and Rafferty, Reference Brooks and Rafferty2010), undergraduate courses had to wait until the first course was established in 1966 at Edinburgh University.

Countering this trend, a broader set of historical and cultural forces in Britain may have played a role in delaying the move to a graduate policy. There is a strong public perception that nurses do not need degrees to be good nurses, they only need to be kind to care. It is worth considering whether these ‘natural’ emotional attributes like kindness, in a profession dominated by women, are the gendered ideas which lie behind the lack of engagement of nurses in strategy and policy-making. Periodically, the media condemns nurse graduates as being ‘too clever to care’ and ‘too posh to wash’. These charges seem to resonate with a section of public opinion that harkens back nostalgically to a ‘golden age’ of nursing (Gillett, Reference Gillett2014). Gladys Carter may have been right when she suggested in 1939 that what was needed in nursing education was a ‘high wind of criticism and a bonfire for prejudices…’, a theme that continues to influence debate. The next section of this paper therefore considers the policy trends leading up to the present policy position, the urgent need to tackle the ‘bonfire for prejudices’ and craft a strategy to facilitate the engagement of nurses in policy and decision-making.

Policy by drift

The move towards university status with degree entry into practice was incremental, the product of professional advocacy, combined with the unintended consequence of the implementation of the Community Care Act 1986, which moved nursing into higher education en masse, but at diploma level. Evidence on how holding a bachelor’s degree prepared nurses to better understand patient outcomes, and specifically mortality, began to emerge in the United States in the early 2000s and has subsequently been added to with comparative data from across Europe (Aiken et al., Reference Aiken, Sloane, Bruyneel, Van den Heede, Griffiths, Busse, Diomidous, Kinnunen, Kozka, Lesaffre, McHugh, Moreno-Casbas, Rafferty, Schwendimann, Tishelman, van Achterberg and Sermeus2014). Two factors within the control of nurse managers, planners and decision makers are the basis on which they make recruitment decisions and the day-to-day management of clinical care. Investment in educational capacity as reflected in degree status by holding a bachelors degree and workload management have been demonstrated to impact outcome, and together to yield a double dividend for clinical and organisational outcomes in terms of reducing mortality across a range of surgeries. These include aortic aneurysm repair and survival from cardiac arrest as well as readmissions (McHugh et al., Reference McHugh, Rochman, Sloane, Berg, Mancini, Nadkarni, Merchant and Aiken2016). In a recent EU-funded study of nurse forecasting in 12 European countries (RN4Cast) deaths were significantly lower in hospitals with more bachelor’s educated nurses and fewer patients per nurse (Aiken et al., Reference Aiken, Sloane, Bruyneel, Van den Heede, Griffiths, Busse, Diomidous, Kinnunen, Kozka, Lesaffre, McHugh, Moreno-Casbas, Rafferty, Schwendimann, Tishelman, van Achterberg and Sermeus2014). Every one patient added to a nurse’s work load was associated with a 7% increase in deaths after common surgery. Every 10% increase in bachelor’s educated nurses was associated with 7% lower mortality. If all hospitals in the 12 countries in our study had at least 60% bachelor’s nurses and nurse workloads of no more than six patients each, more than 3500 deaths a year might be prevented (Aiken et al., Reference Aiken, Sloane, Bruyneel, Van den Heede, Griffiths, Busse, Diomidous, Kinnunen, Kozka, Lesaffre, McHugh, Moreno-Casbas, Rafferty, Schwendimann, Tishelman, van Achterberg and Sermeus2014).

Growing the graduate base with workload management has been shown to exert a multiplier effect upon patient outcomes, and is vital to generating an infrastructure for implementing evidence in practice and ensuring that patients gain access to effective interventions in a timely fashion. Data from the RN4Cast study indicate that both in terms of the investment in bachelors prepared nurses and workload the baseline position of nursing in England is in urgent need of improvement.

In terms of hospital rankings on nursing investments in education and workload-related practices in our EU study of 12 countries, nurses in England ranked at the lower end in many categories: 8th in education level; 7th in terms of staffing and resource adequacy; 10th in terms of skill mix; work environment quality; 11th in terms of burnout and high nurse intent to leave job, meaning they had amongst the highest levels of burnout of nurses across the EU apart from Greece, Poland and Spain (Aiken et al., Reference Aiken, Sermeus, Van den Heede, Sloane, Busse, McKee, Bruyneel, Rafferty, Griffiths, Moreno-Casbas, Tishelman, Scott, Brzostek, Kinnunen, Schwendimann, Heinen, Zikos, Strømseng Sjetne, Smith and Kutney-Lee2012). Similarly, compared to its peers in other high income countries outside of Europe such as Canada, the United States and Australia, England has been under-producing domestically trained nurses for the past decade relying instead on internationally recruited nurses, including an increasing proportion from the EU and agency nurses to fill skills gaps. Brexit threatens to add further pressure to the EU as a source of recruitment for the nursing workforce (Leone et al., Reference Leone, Bruyneel, Anderson, Murrells, Dussault, Henriques de Jesus, Seremus, Aiken and Rafferty2015). The United Kingdom has also lagged behind in terms of the OECD average in its recruitment profile according to the latest data in 2016 (OECD, 2016). The number of nurses has increased in nearly all OECD countries since 2000 from 8.3 million to 10.8 million in 2013. At a time when many of its peer countries such as Canada, the United States and Australia have been investing in educating more nurses to meet demographic demand and disease burden, the United Kingdom has remained stubbornly static, dipped or only made temporary adjustments to an unhealthy boom bust cycle of recruitment (see Figure 1).

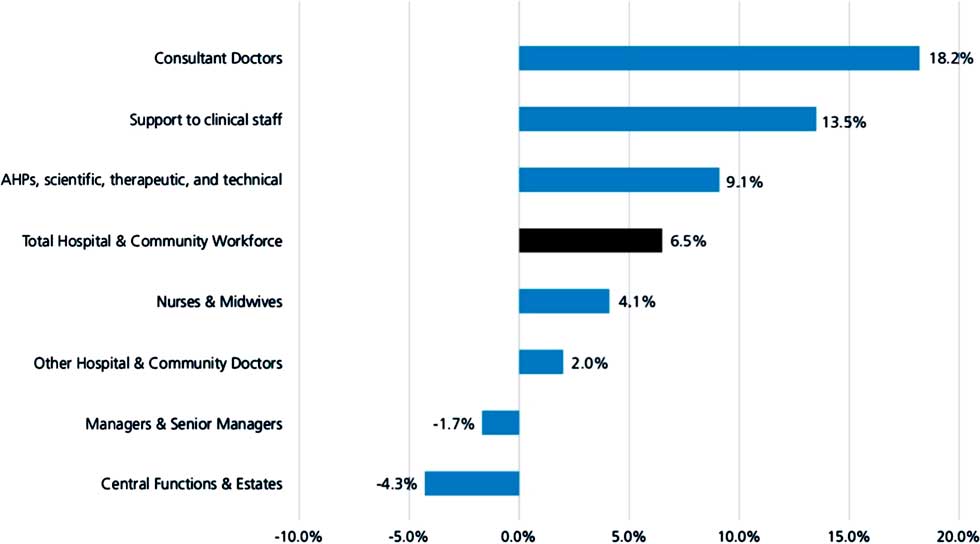

Figure 1 Percent increase of substantively employed staff by group, 2012–2017. Source: NHS Digital.

In times of austerity, nursing has tended to be been used as a ‘soft target’ for savings by managers and decision makers. The static position of nurse numbers over the past decade contrasts starkly with the position for doctors, whose numbers have been steadily climbing to meet growing demand and demographic pressures, and with plans to recruit a further 1500 doctors for training (Buchan et al., Reference Buchan, Seecombe and Charlesworth2016). While more doctors may meet growing demand they also generate demand, whose toll falls mainly on nurses. The tax on nurses can be seen in burnout, vacancy, turnover, agency and temporary staffing rates in Trusts. Last year’s decision by the Migration Advisory Committee to place nursing on the Shortage Occupation List in the United Kingdom was the culmination of years of poor workforce planning, pay restraint and weak decision-making on staffing issues (in 2015–2016 the vacancy rate was 10%). The supply of nurses has failed to keep up with this rapid growth in demand. National Statistics data revealed that in the NHS in England and Wales, between 2013 and 2015, there had been a 50% increase in nursing vacancies (from 12,513 to 18,714). The data also show that nearly three-quarters of NHS trusts and health boards were actively trying to recruit from abroad (Office of National Statistics, 2016).

Not only does this mismatch signal a lack of a joined up, multi-professional approach to planning at national and local levels, but also the different value that is placed on doctors and nurses within the service. Strategic failures in workforce planning over a protracted period of time have consequences for staff as well as patient experience and outcomes of care. Failure to invest adequately in the largest health care workforce is reflected in variations in retention, turnover, staffing levels and vacancies and consequently care outcomes for patients on a scale previously unseen in medicine. The figures show 96% of acute hospitals failed to provide the planned number of registered nurses to cover day shifts in October 2016 (Lintern, Reference Lintern2017). It is not only the position in acute care setting which gives cause for concern, but also nursing in the community, which has been allowed to deteriorate. Over the past 10 years, the number of district nurses has dropped by 28% to just under 6000, while the wider community nurse workforce had shrunk by 8% to 36,000 (Maybin et al., Reference Maybin, Charles and Honeyman2016) at a time when the workforce is ageing and the policy intent is to shift care into the community.

Policy has neither kept pace with growing demand, nor been driven by the available evidence. Rather it has been allowed to drift in a downward direction as finances have tightened. Furthermore, one of the main policy levers for recruitment, the bursary or state subsidy for nursing entrants, has recently been removed by the government leaving recruitment to the fate of student loans. At the time of writing we have more than a 20% drop in applications for nursing places at universities. While there are proposals to create degree apprenticeships by the Higher Education Funding Council for England this is as yet an unknown quantity. Brexit threatens to exacerbate the situation further. Recruitment shortages in 2010 were filled by nurses from the EU, upon which the United Kingdom has become increasingly reliant. The numbers of nurses from EU countries have dropped dramatically in the past year (Buchan et al., Reference Buchan, Seecombe and Charlesworth2016). Furthermore, cuts to post qualification training of up to 50% in some Trusts are likely to impact, too, on the EU recruitment and retention of nurses. Continuing professional development opportunities is a major incentive in the absence of such policies in countries such as Portugal, hit heavily by austerity (Leone et al., Reference Leone, Bruyneel, Anderson, Murrells, Dussault, Henriques de Jesus, Seremus, Aiken and Rafferty2015). When we add to this scenario caps on funding agency and temporary staff, Cohen’s contention that nursing reflected the flaws in the planning system seems to be compelling and starkly illustrated by the strategic failures of workforce planning described above.

Policy by dilution

We have to ask ourselves: how has this situation been allowed to happen? Maybin and Klein (Reference Maybin and Klein2012) describe the different ways in which rationing health care can occur, one of which is dilution. Dilution itself can take different forms. Rationing by dilution refers to a situation where a service continues to be offered but its quality declines as cuts are made to staff numbers, equipment and so on. One of the consequences of understaffing is that care is compromised (Ausserhofer et al., Reference Ausserhofer, Zander, Busse, Schubert, De Geest, Rafferty, Ball, Scott, Kinnunen, Heinen, Strømseng Sjetne, Moreno-Casbas, Kózka, Lindqvist, Diomidous, Bruyneel, Sermeus, Aiken and Schwendimann2014; Ball et al., Reference Ball, Murrells, Rafferty, Morrow and Griffiths2014). Lower staffing levels are associated with higher levels of care left undone, particularly the ‘human touch’ of comforting or talking with patients and educating patients and their family. England was among the group with the highest levels of care left undone overall compared with other European countries, Switzerland, Belgium, Poland and Spain (Aiken et al., Reference Aiken, Sloane, Bruyneel and Van den Heede2013). Time-consuming activities, or psycho-social activities for which the required time-effort is difficult to estimate were more often omitted and seem to receive the lowest priorities. According to Ball et al. (Reference Ball, Murrells, Rafferty, Morrow and Griffiths2014) 78% of those in the best staffed environments (with 6.13 patient or fewer per RN) reported some care was missed on their last shift, compared with 90% of those with lower staffing levels (7.4 patients or more per RN). RN staffing level was significantly associated with missed care for eight of the 13 care activities. The effect of staffing was strongest for ‘adequate patient surveillance’, ‘adequately documenting nursing care’ and ‘comforting/talking with patients’ (Ball et al., Reference Ball, Murrells, Rafferty, Morrow and Griffiths2014). The study found a strong relationship between the number of items of missed care and nurses’ perception of quality of nursing care. This is essential not only for the quality and safety of care but the resilience and sustainability of the health system. As the so-called Swiss army knife of the NHS, many other workers rely upon nurses in order to operate effectively themselves. The Royal College of Physicians remarked upon the consequence of understaffing for medical work. The survey of doctors-in-training demonstrated that nursing shortages take their toll on both the workload of doctors and on patient care; nearly all trainees (96%) report that gaps in nursing rotas are having a negative impact on patient safety in their hospital (Royal College of Physicians, 2016). The nursing function cannot perform at its most efficient if there are too few staff to provide necessary care.

It is the dilution not only of qualified staff numbers, but also skill mix which matters. For the first time since 1943, the NHS in England is poised to implement a second grade of nursing associate to plug the skills gap in the shortage of RNs. This decision effectively reverses a policy in the 1980s to eliminate the enrolled nurse, the antecedent to the nursing associate, which was introduced during WW2 to deal with the acute shortage of RNs during the wartime emergency. The enrolled nurse was phased out on the grounds that this was an exploited role with poor career prospects. Incumbents were absorbed by conversion courses into the RN workforce in what was a silent but successful policy achievement in assimilating and upgrading the workforce to an all RN level. At the time of writing, the nursing associate role is being piloted, evaluated and a consultation launched. It is worth noting that England’s track record of adding new workers into the skill mix is poor. Assistant practitioners and physician assistants have limited progression opportunities, and though nursing associates may be able to transition into degree courses there is the danger that they will become the default grade in the longer term, diverting energy from building quality in the RN qualified workforce. The policy is also based on flawed foundations which ignore the available evidence on the risks of diluting skill mix which are associated with higher mortality for patients (Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Ball, Murrells, Jones and Rafferty2016).

So far England is alone of the devolved administrations in taking this step to solve the shortage, with Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland preferring to concentrate on building a graduate pathway and career structure. At present, the shape of the career structure for nurses is heavily concentrated in lower grades, band 5 and 6, with only a narrow canal of advanced and senior roles. In the current environment there are too few prospects for promotion to senior grades, which is demotivating, not only for those in the system but also for the next generation seeking opportunities. It is clear that there is a need to produce and promote advanced practice nurses to meet growing demand for long-term conditions (Rafferty et al., Reference Rafferty, Xyrichis and Caldwell2015). Advanced practice nurses have also proven effective substitutes for doctors in taking on certain routine tasks and investigations, such as endoscopy, achieving comparable and in some cases better results (Limoges-Gonzalez et al., Reference Limoges-Gonzalez, Mann, Al-Juburi, Tseng, Inadomi and Rossaro2011). Senior nurses provide an essential leadership function and role models for more junior staff in nursing as well as strategic and operational support for health care organisations. There is a need to grow this cadre of nurses. Inadequate investment in producing our own nurses has forced us into the vicious circle of falling back on internationally recruited nurses and agency, which have poorer outcomes in terms of patient satisfaction and ultimately satisfaction with the NHS (Aiken et al., Reference Aiken, Sloane, Rafferty, Bruyneel, McHugh, Maier, Moreno-Casbas, Ball, Ausserhofer and Sermeus2017). Other high income OECD countries have been investing in their domestic supply of nurses, growing their graduate population, and the United States, which had one of the major shortages, has brought its workforce into balance. Evidence demonstrates even small deviations in planned to actual nurse to patient ratios impact patient safety (Needleman et al., Reference Needleman, Buerhaus and Pankratz2011). The recommended 1:8 compares in England unfavourably with Australia and the United States ratios of 1:6 and 1:4, even though these are crude metrics. Wales has been successful in changing its workforce policy by enacting staffing legislation providing a natural experiment with which to compare with England. This significant policy development demonstrates the importance of effecting a policy shift with a strong lobbying platform, a well-orchestrated campaign to mobilise support beyond nursing (especially with the public) and a strong evidence base.

While we have made significant strides in generating evidence in key workforce domains, this is not being put into practice. Significantly, the current nurse staffing policy in England uses the currency of care hours per patient day, which effectively combines the inputs of registered and non-registered staff (NHSI) by passing evidence on skill mix and patient outcomes. Lord Carter’s productivity review (Carter, Reference Carter2016) argues that conventional measures such as whole-time equivalents or staff–patient ratios did not reflect varying staff allocations across the day, and proposes the use of care hours per patient day, calculated by adding the hours of registered nurses to those of health care support workers, and dividing the total by every 24 hours of inpatient admissions. The new metric adopted from other countries such as the United States and Australia has never been trialed in the UK NHS. One concern is that it will dilute the registered nurses’ contributions to care, so that such a merger may be a ‘fatal flaw’ in patient safety (Merrifield, Reference Merrifield2016).

Leading change for better health care tomorrow?

Where then does this leave nurses as change agents for better health care tomorrow? The role of change agent can take many forms. Nurses have been active in generating much of the evidence to underpin workforce policy. History tells us though that one of the key conditions for change to be effected has been the convergence between the interests of the profession and those of the state (Rafferty, Reference Rafferty1996; Traynor and Rafferty, Reference Traynor and Rafferty1998). Often change has emanated from a campaign or lobbying effort to mobilise and make the change happen. This is one way of trying to halt the politics of drift. The development of nurse prescribing was only won after a battle with the BMA and a campaign and lobbying effort countering medical opposition (Shepherd et al., Reference Shepherd, Rafferty and James1999). Securing the state registration of nurses in the United Kingdom in 1919 was a battle lasting almost 30 years and the product of significant and sustained lobbying activity, campaigning and political leadership on the part of nurses. But it was also part of a convergence of interests between the profession and the state in providing mobility within the labour market, and a standardised qualification in the light of proposed health reform (Rafferty, Reference Rafferty1996).

The expansion in universalising access to care has been a stimulus to nurse recruitment, education and expanding graduate pathways to advanced practice in the United States. Again this process and effort has been underpinned by a campaign in the US supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Institute of Medicine and, significantly, the Associated of Retired Persons, arguably the most powerful NGO in the United States. Targets have been set to increase the numbers of graduates in the workforce and advanced practice nurses (Institute of Medicine, 2010). The campaign which resulted from these changes has not been mirrored in the United Kingdom even although we have spiralling demand for health care services. There is no corresponding workforce policy being formulated to meet growth in the demand for care volume and complexity in England. Rather, there are signs of movement in the opposite direction with the reintroduction of degree apprenticeships that muddies the different routes to registration and strengthens the hand of employers over education.

The body responsible for workforce planning, Public Health England (2017), has presided over one of the most fiscally stringent periods in the recent history of health care following from the financial crash of 2008, but has failed in its mandate to deliver a multi-professional workforce plan. We are struggling to meet growing demand from an ageing population with multi-co-morbidities, the crisis in social care, rising public expectations, increasing use of technology, slow to no growth in budgets and cuts in many places cuts to nursing numbers. Numbers of nurses should be rising in line with doctors to meet demand, and yet we seem to be caught in a historical holding pattern preventing us from moving forward in capacity building and adding much needed strength to where areas of highest need, e.g. district and community nursing. If the largest segment of the workforce falters, the rest of the system will be vulnerable too.

There is ample evidence to suggest that women are disproportionately impacted by austerity cuts (Bennett, Reference Bennett2015). As a female dominated profession, nursing in England seems to be shouldering an undue burden of austerity. The workforce metrics for the two largest segments of the health care workforce, doctors and nurses, indicate a growing divide and marked misalignment in growth rates over the past decade at a time when demand has been rising steeply. Ensuring the participation of nurses in the design of policy will release frontline expertise and know-how into the system. This is not only about good employment practice (West et al., Reference West, Maben and Rafferty2006) but the need for shared governance to be scaled up. The magnet hospital model offers the best evidence-based approach to achieve key policy goals simultaneously: better retention of nurses through positive practice environments, better outcomes for patients, and shared governance for frontline nurses. Many other industries recognise the utility of the providers of frontline delivery are best placed to redesign and improve systems, yet in health care we often ignore or squander the opportunity. This has to be a priority for any change strategy moving forward and written into the governance frameworks of organisations (Aiken et al., Reference Aiken, Clarke, Sloane, Lake and Cheney2008).

On the campaigning front, nurses have been active as a pressure group, formulating a change agenda through a safe staffing alliance representing a coalition of unions, professional associations, the Patients’ Association, senior nurse leaders, academics and activists. This alliance has been campaigning for a more rigorous, evidence driven approach to workforce planning (www.safestaffingalliance.org.uk). Within the United Kingdom the devolved countries have responded differently to workforce and staffing pressures. As with some jurisdictions in the United States such as California and Australia, notably Victoria and now Queensland, staffing legislation has been implemented to mandate staffing ratios in terms of limiting the number of patients nurses can care for in the course of a shift. Some evaluation of the impact of the legislation on patient safety has been undertaken within California (Aiken et al., Reference Aiken, Sloane, Cimiotti, Clarke, Flynn, Seago, Spetz and Smith2010) and Queensland, with a pre- and post-test evaluation study design. At the time of writing, it is too early to comment on outcomes. Within the UK Wales has passed nurse staffing legislation, which is in the process of being implemented. The campaign led by the Royal College of Nursing in Wales was orchestrated with a clear strategic plan and executed with military precision. We now have an interesting ‘natural experiment’ in which two jurisdictions within the same country have adopted different approaches to staffing in acute general medical and surgical care, the setting where the evidence base is strongest. Learning from positive practice models and scaling up could be a helpful intervention (Kroezen et al., Reference Kroezen, Dassault, Craveiro, Dieleman, Jansen, Buchan, Barriball, Rafferty, Bremner and Sermeus2015).

Conclusion

Nursing is a major part of the solution to building a better future in health care. Future policy options need to consider scaling up the participation of nurses in designing future policy, rather than just being expected to implement it. There are many policy interventions that will improve health outcomes for the population but they need support to make change happen, and to do so means embedding the nursing voice in decision-making at every level of the system. Garnering the lessons from safe staffing initiatives, such as those which have translated into legislation in California, Victoria and Queensland in Australia, and now Wales in the United Kingdom, will provide further case studies of nurses leading change. Leveraging the lessons from these campaigns and strategising across health jurisdictions will provide a policy option for Canada and elsewhere. Within Canada, there is growing concern about nursing workloads (MacPhee et al., Reference MacPhee, Kramer, Brewer, Halfer, Hnatiuk, Duchscher, Maguire, Coe and Schamlenberg2017). Momentum is building to debate staffing legislation in British Columbia. Nurses have managed to make changes, expanding prescribing powers and scope of practice in increasing access to services, and breaking the link between the economic needs of hospitals and nurse training. Investing in a better educated workforce, in sufficient numbers able to work at the full scope of practice, will enable an enhanced value proposition for the profession and public and secure a better future for health care.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the editors, peer viewers and Olga Boiko, Julie Hipperson and Fay Bound Alberti for their helpful comments.