Introduction

The personal and societal impact of dementia and driving is substantial. Drivers with dementia have significantly greater risk of accidents, injury and loss of life compared with age-matched drivers without cognitive decline (Dobbs, Reference Dobbs2005; Vaa, Reference Vaa2003). The transition to non-driving comes at significant personal cost, including restricted community mobility, increased risk of depression, anxiety, loneliness and isolation, identity loss, and grief (Byszewski et al., Reference Byszewski, Molnar and Aminzadeh2010; Liddle et al., Reference Liddle, Bennett, Allen, Lie, Standen and Pachana2013; Windsor et al., Reference Windsor, Anstey, Butterworth, Luszcz and Andrews2007), and possible premature institutional care placement (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Gange, Muñoz and West2006). Timing of the decision to stop driving is critically important. If the decision to cease driving is delayed, then loss of insight into declining driving abilities potentially exacerbates the challenges of stopping (Dubinsky et al., Reference Dubinsky, Stein and Lyons2000). While prior qualitative research has examined issues relating to dementia and driving cessation from the perspectives of people living with dementia and their family carers (Adler, Reference Adler2010; Byszewski et al., Reference Byszewski, Molnar and Aminzadeh2010), and health professionals (Liddle et al., Reference Liddle, Bennett, Allen, Lie, Standen and Pachana2013; Perkinson et al., Reference Perkinson2005), to date the perspectives of general practitioners (GPs; also known as primary care physicians or family practitioners) who play a key role in monitoring driver safety and retirement with their patients with dementia, are less well described.

In Australia, as with most other countries, primary care physicians are often the first medical professional approached to identify changes in functioning potentially impacting driving competence in their patients (Austroads, 2016; Hakamies-Blomqvist et al., Reference Hakamies-Blomqvist, Henriksson, Falkmer, Lundberg and Braekhus2002; Hawley and Galbraith, Reference Hawley and Galbraith2008; Hoggarth, Reference Hoggarth2013; Jang et al., Reference Jang2007; Sims et al., Reference Sims, Rouse-Watson, Schattner, Beveridge and Jones2012). Similar to other countries, system level issues exist which impact raising driving with patients with dementia and successful management of the process in primary care, such as constraints of time in consultation, competing priorities, and mandatory reporting guidelines that vary by location. Furthermore, with limited information and prior training about how to evaluate fitness-to-drive in primary care, it is a poorly resourced area of clinical dementia care.

GPs are often reluctant to raise the issue of driving with their patients with dementia because they fear the negative effects on the doctor-patient relationship (Hoggarth, Reference Hoggarth2013; Jang et al., Reference Jang2007; Sims et al., Reference Sims, Rouse-Watson, Schattner, Beveridge and Jones2012). Conversely, caregivers and family members may prefer that GPs deal with the issue, because they fear the conflict that arises from discussions about driving, or actively intervening in restricting the person with dementia’s driving (Adler, Reference Adler2010; Byszewski et al., Reference Byszewski, Molnar and Aminzadeh2010; Liddle et al., Reference Liddle2015; Perkinson et al., Reference Perkinson2005). GPs acknowledge that they lack confidence in managing driving issues with patients (Moorhouse et al., Reference Moorhouse, Hamilton, Fisher and Rockwood2011; Sims et al., Reference Sims, Rouse-Watson, Schattner, Beveridge and Jones2012). Family members and persons with dementia may lack insight into the effects of dementia on driving, and awareness that capacity for safe driving requires more than memory. It is necessary to identify effective strategies GPs might employ to navigate driving cessation with patients with dementia, to support them in their role as advocates for their patients’ health.

This difficult issue is further complicated by lack of access to consistent medical information and advice, such as evaluating driver safety and mandatory reporting responsibilities (Carr and Ott, Reference Carr and Ott2010; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Rouse-Watson, Beveridge, Sims and Schattner2012; Molnar et al., Reference Molnar, Patel, Marshall, Man-Son-Hing and Wilson2006; Rapoport et al., Reference Rapoport2018). Despite an existing body of research, a standardized approach to medical assessment of driving for patients with dementia remains an issue across many countries. The aim of this qualitative study was to explore the experiences of GPs in managing the issue of driving cessation with their patients with dementia, and to identify the strategies they report using to address the challenges or facilitate the process.

Methods

Setting

In Australia, general practitioners are considered as medical specialists. They are the first point of contact with the health system in most cases. Over 80% of Australians visit their GP at least once per year. They can choose freely – there are no patient lists and patients sometimes see doctors from different practices. Referral to specialist practitioners and many allied health service providers requires a referral from the GP. Funding is via a universal health insurance scheme (Medicare). Most GPs see patients every 10-15 minutes, with longer consultation times possible for complex problems. There is provision for health checks, and complex care planning for vulnerable people, including older Australians.

Design

This qualitative study was informed by principles of interpretive description (Thorne, Reference Thorne2008), which aims to generate knowledge relevant for a clinical context of applied health disciplines (Thorne et al., Reference Thorne, Kirkham and O’Flynn-Magee2004). The method aims to facilitate understanding of the context in which a problem is being observed, going beyond averaging responses to capitalising on the interaction among perspectives and the shared experiences of respondents (Thorne, Reference Thorne2008). Therefore, data were collected through a series of dynamic focus group discussions with GPs working in busy primary care settings in metropolitan and regional areas to collect their views of the issues, including potential barriers and facilitators, relevant to managing driving cessation with their patients with dementia.

Recruitment

Purposive sampling techniques were used to recruit GPs from primary care settings in metropolitan and regional practices in South East Queensland, Australia. Potential participants were made aware of the study through their place of work. Primary Care settings that had a high likelihood of seeing older adults were first identified from a full list of Primary Heath Networks in the South East Queensland area. The Practice Principal and Practice Manager from each of these settings was emailed a Study Information Sheet and invitation to participate. If interested in the study, potential participants or their practice managers were asked to contact the investigator to arrange a suitable date and time to conduct the focus group discussion. The researcher followed up any non-respondents. Ten general practices were approached to participate, and five of those agreed. The reasons given for declining to participate were that the practice could not afford to release the GPs for the required time, or because of staff absences there were too few staff available for a focus group. There were no systematic differences between the participating and non-participating practices. That is, these were similar in terms of number of practicing GPs (range 4 – 13, M = 8), proportions of suburban and regional practices, or proportions servicing a greater number of older people. Five focus groups, involving 29 GPs, were conducted across participating practices, either before opening hours or during lunch breaks, and catering such as a light breakfast or lunch, was provided to participants.

Procedure

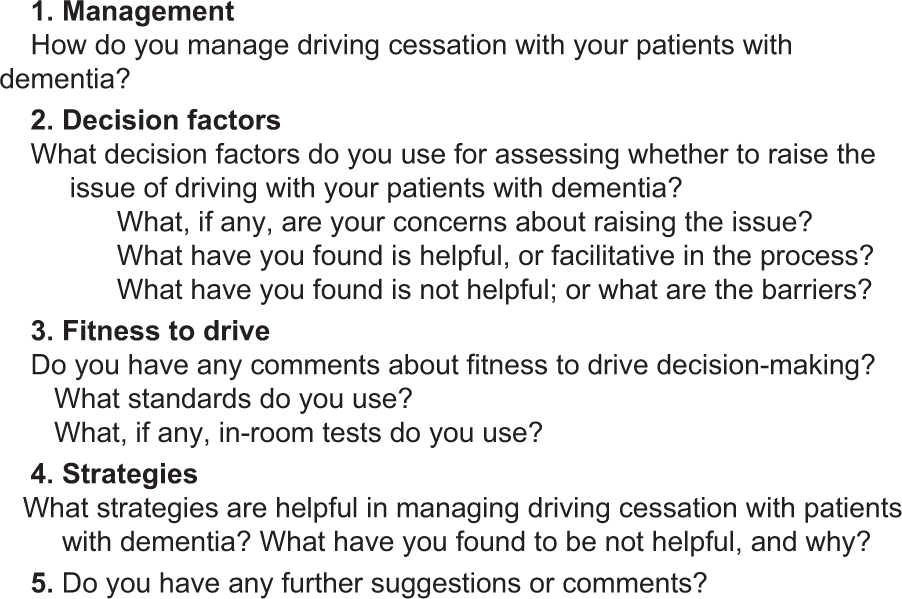

Focus groups followed a set of basic guide questions (Figure 1) that were intentionally left open because the aim was for the discussion to be guided by the participants, their experiences, and issues that they raised. To begin, the purpose and procedure of the study was briefly outlined, and informed consent was obtained – including permission to audio record the discussions. Demographic information such as gender, age, experience, and location, was collected from participants on a separate sheet. This was followed by a 90-minute moderator facilitated discussion. The audio-recorded discussions were transcribed verbatim, and thematically analysed. To enhance rigour, peer checking occurred throughout all stages of the analytic process, researchers contributed to the revision of concepts and themes and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Reflexivity was promoted through introspection and reflection on notes taken during the focus groups discussions.

Figure 1. Focus group discussion guide and prompt questions.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of The University of Queensland, Australia. To ensure confidentiality in the analysis of data, participants’ identities were concealed in the focus groups’ verbatim transcriptions by omitting participants’ names and other potentially identifiable characteristics, e.g., the practice address. Because anonymity was assured and because the focus groups’ discussions were dynamic, it was not possible to attribute particular quotes to individual participants in the text, e.g., P1, P2, etc. Furthermore, as none of the issues reported were related to urban or regional locations it was not necessary to identify these individually.

Analysis

Constructing an understanding of the data began with sorting the data into a manageable form through open broad-based coding of the transcripts, and concept mapping to explore patterns of relationships within the coded data (Thorne, Reference Thorne2008). Two researchers (T.S. and a research assistant) read the transcripts several times to get a conceptual impression of the discussions and developed a coding scheme based on the relevance of concepts to the research question, and the importance of any departures from it. The codes were then catalogued as conceptual themes by T.S. The concepts, themes and representative quotes were checked by J.L., which generated some amendments to themes and definitions, until consensus between coders was achieved. Credibility of the findings was derived through discussion and reflection between T.S. and G.M., a practising GP who contributed insights into the clinical practice issues and perspectives of GPs as well as client groups. That is, the generated themes were checked with other members of the research team who were not involved in the interviewing process, and any uncertainties or omissions about the thematic analysis were resolved through discussion.

Findings

Participants

The findings reflect the experiences of the 29 primary care physicians (F = 48%) who work with patients with dementia who are transitioning from driving to non-driving in metropolitan (41%) and regional (59%) practices in South East Queensland, Australia. Participants’ mean age was 48.6 years (SD = 13.3, mode = 30) and had a mean 20.6 years practice experience (SD = 14.4, mode = 15.0).

Overall, four main themes that illustrate practice approaches taken by GPs in managing driving cessation with patients with dementia emerged from the analysis. These included, (i) Considering the individual – taking a case by case approach; (ii) GP-patient relationships may hinder or help – drawing on positive relationships and knowing how to manage potentially detrimental relationships; (iii) Resources to support raising driver retirement – personal and professional experience, knowledge and practical supports; and (iv) Ethical dilemmas and ethical considerations – “what keeps us up at night,” under which nested several sub-themes, as shown in Table 1. Several issues that cut across these themes emerged from the focus groups discussions.

Table 1. Themes and example statements derived from the focus groups

Considering the individual – taking a case by case approach

In characterizing their approach and the support they needed, participants indicated that, although a standard approach would make things simpler, they recognized that there was “no one size fits all” when working with patients with dementia who must inevitably adjust to life without driving. While GPs have a sense of there being optimal ways of managing driving cessation they acknowledged that what works for one patient may not work for another. The complexities are highlighted in the theme “Considering the individual.”

Preparation and timing were identified as critical in relation to managing driving cessation with patients with dementia, including when to raise the issue, to conduct an assessment of driver fitness, and to impose any limitations or restrictions to driving. However, there was also recognition that simply mentioning the future need was not sufficient in improving readiness. For some patients with dementia, coming to terms with stopping driving required a deliberate change in mindset about what their life would be like without driving and letting others do the driving, or using alternative modes of safe transport such as using friends or community transport support. Preparation was identified as key to facilitating the process. For example, one respondent framed retiring from driving as being similar to retiring from work, and informs patients that “there will be a time when you retire from driving and how do you think you’ll know when that time is.” According to this perspective, if a patient comes to an understanding early in the diagnosis process that retiring from driving is normalized and is something that they should plan and work towards, then it becomes easier for them to accept and act on their doctor’s advice.

Furthermore, while GPs recognize that raising the subject at an early stage with patients was central to a better transition, it was not always possible because of the difficulty of objectively identifying when an individual’s driving was likely to be impaired enough to warrant cessation. Lack of insight into disease progression on the part of the patient complicated the process even further, according to respondents. Education around the disease trajectory and its impact on driving safety were seen as key to patients accepting and following their GP’s advice, and to avoiding involuntary restrictions or licence cancellations.

Conversely, many of the GPs noted that when preparation was not done or not possible within the process, the transition was harder for patients and gave rise to a more crisis-driven approach. They identified that unprepared patients often reacted with the most grief or anger – emotions that are less likely to lend themselves to taking the advice of their GP. It was noted that there was no way to stop a patient going to another doctor after their licence was revoked by their GP. “We do lose patients when we decline licences, unfortunately they’ll think, oh, well, I’ve got another doctor who will give me a licence, but that can be really challenging as well.” Participants commonly mentioned ‘doctor shopping’ – seeking permission to drive from another doctor who was potentially unaware of their diagnosis – as part of a maladaptive response, especially if the patient did not have insight into their driving abilities. As one GP stated “I had a lady — she drove her car into the bank … and she came to me the next week to get her licence and obviously I didn’t give it to her, and the next day I got a call from another practice saying that she was transferring her general practice [care] to someone else.”

Making assessments relevant to the individual and the lack of in-office indicators of fitness to drive with patients with limited insight into their own driving abilities were discussed at length. When asked to report the tests that were being used, the majority reported using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and Clock Drawing task, as well as the Trails Making Test, and Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE). The problem with these paper and pencil tests, they stated, was that most lacked face validity with their patients. Some identified that tests played a role in patients understanding the driving recommendations and it was important they could perceive the relevance of the tests to driving, and also perceive their own performance accurately. In some instances because in the GPs opinion the patient was not fit to drive but had poor insight, participants mentioned using tests that they themselves devised to be impossible for the patient to pass, “I got my tendon hammer and I got them to hold it like that, and I dropped it and said, ‘You have to grab it before it falls,’” or they were using physical symptoms, such as vision tests, as reasoning for cessation. While GPs acknowledged the problems with these various tests, and that most were unreliable metrics of actual driving ability, they resorted to their use in the absence of objective off-road testing being available within the setting, and when it was their intention to cancel a licence and the GP wished to lessen the negative impact of the decision on the relationship, and could point to the “test result” as the reason.

GP-patient relationships may hinder or help — drawing on positive relationships and knowing how to manage potentially detrimental relationships

In framing their approach to managing driving issues, participants indicated relationships played a complex and pivotal role. Positive relationships facilitated management of and adjustment to driving cessation with patients with dementia and their family members. However, relationships could also be detrimental to the process. This theme was underpinned by emotional responses, balancing key people, families’ involvement with the patient and their GP, and other relational capital, such as having other health professionals support the GP’s recommendations to the patient.

A major concern for all participants was the potential negative impact of removing driving privileges on the doctor-patient relationship. Consequently they expressed a reluctance to raise the issue with their patients. This was in contradiction to the stated importance of preparation and readiness. Participants spoke of how removing a patient’s licence can have negative ongoing consequences for patients’ overall health, such that they stop coming to the GP for other health related issues, e.g. blood pressure examinations. For example, as one respondent said of having to revoke a patient’s licence, “people see that as an act of a motion of no-confidence in them – you don’t trust them anymore, [so] they don’t trust you.” In an “ideal world” it was suggested, driving cessation would be considered as a normal part of aging or a diagnosis of dementia, and someone else, other than the GP, would conduct assessments and make decisions about annual driving licence renewal.

Using positive relationships strategically while facilitating the transition reduced the emotional toll for everyone involved. Possessing more professional experience and using the long-term relationship with the GP could mean patients and family had more confidence that the person with dementia was considered in making driving decisions. As one respondent stated, if you have “known them [patient] for a long time and you have some collateral with them, and rapport and you maybe get a chance to ease it out.” While strategies involving the individual’s family and/or partner were noted as very important to the process, dependent upon certain factors family involvement could either help or hinder. For example, family support can “make the world of difference” as one GP expressed. However, families and partners were not always supportive of the person with dementia stopping driving, especially if family members felt that they would be inconvenienced because of a lack of alternative transportation options.

The majority of the respondents felt that drawing on a broader professional network and having multiple professionals expressing the same opinion was helpful in having the patient and family accept the outcome. Such a process would make the decision appear fairer and more objective. The consensus was that if there was an external, independent assessment of a patient’s driving ability that the doctor could point to and say “well based on this, we can’t allow you to continue driving,” then such assessments may seem more satisfactory to the patient and help to maintain the therapeutic relationship. In the absence of an external, third-party opinion, a successful strategy used by some was to engage the support of another GP within the same primary care practice and have that other GP provide the patient “with a second opinion,” informed by the full medical history, which may be absent in the case of doctor shopping.

Resources to support raising driver retirement – personal and professional experience, knowledge and practical supports

Participants identified resources that they drew upon, needed or wished were available, with this theme including knowledge, education, and supports. Knowledge related to an awareness of the mental health implications of driving cessation, available support services, dementia per se, driving legislation, and the research literature and evidence. Keeping abreast of the available resources, and in particular the available literature was identified as difficult for busy medical professionals working under pressure. Practitioners noted that, in a standard 10-15 minute consultation, it was often difficult to notice the functional deficits that may impact driving. While professional experience and a relationship with the patient were sometimes an advantage, participants expressed that fitness to drive decisions should not even be their responsibility, because they wished to be a patient advocate.

Identifying the problem relating to driving capacity was a major issue. While professional experience and knowledge may be of benefit to those who have dealt with a number of patients with dementia across many years, all GPs reported difficulties with beginning the ‘awkward’ conversation with patients — “the hardest thing for GPs to actually have to do.” There was some discussion around some recent media reports of an ‘imminent cure for dementia’ and driverless vehicles, along with an expressed hope by a few that consequently the issue might not exist in years to come, e.g., “with the cures that have been trialled for Alzheimer’s and with the automated cars… stuff’s changing.”

There was consensus that with more resources things could be done better. All GPs indicated that they lacked an objective way to determine when the disease had progressed to a degree that warranted addressing driving, and an objective way to predict driver performance. Discussion around testing driver fitness suggested that most respondents recognized that the gold standard was on-road assessment. However, the problem with on-road assessments according to respondents was that they were quite expensive, often requiring unviable out of pocket payment by patients.

Having knowledge of supportive infrastructure for patients who are considering retiring from driving and imparting that knowledge was facilitative in conversations with patients. Consequently, when the time came for the individual to cease driving, their independence might be maintained. For example, one GP noted that having their practice nurse go over local transport alternatives with their patients was helpful preparation. Having knowledge of local public and community transport alternatives as well as the individual’s social support networks, were identified as preparatory information to successfully raising the issue with patients. However, keeping up to date with changes in transportation alternatives and ensuring that patients were aware and accepting of these alternatives was outside of the scope of most GPs’ available resources.

Ethical dilemmas and ethical considerations – “what keeps us up at night”

A number of participants identified the complexity of ethical dilemmas and considerations in managing driving with patients with dementia. In terms of fitness to drive, professional responsibility was integral to decision making. GPs expressed uncertainty about their ethical and legal obligations. This theme also captured the emotional responses from GPs to dealing with driving issues with their patients with dementia.

Impact of driving cessation discussions on GPs

An awareness of the massive impact on the patient’s broader life and others of driving cessation decisions was a challenge for GPs. As one noted“It is one of the hardest interactions to have as a GP, especially with long-term patients, and it’s often a relationship breaker.” They acknowledged that the responsibilities and medico-legal implications of their decisions in balancing their duty of care to their patients as well as other road users, could be burdensome. For example, “… often you wake in the middle of the night and think, oh God I don’t know whether I should’ve given that person their licence, what if they kill somebody … the responsibility is very onerous and it’s really uncomfortable when you give somebody a licence and you’re a bit 50/50 either way.” The challenge of preserving their professional relationship with the patient, prolonging the patient’s right to drive, and safeguarding them and other road users was an overwhelming conflict which they felt that GPs, as a whole were not trained or resourced to deal with. For example, “it completely changes our role – it becomes one as an advocate for a community health issue and not the individual’s health.” According to respondents, if patients were not accepting of or angry about the removal of licence privileges by their GP some might ‘sack’ their doctor and not return, while others might return for medical check-ups and to rebuke the GP about having taken their licence. This had an emotional toll for many of the GPs, in particular where there had been a long-standing doctor/patient relationship.

Additionally, there was the ethical dilemma that some older patients visited multiple doctors to find one who will ‘sign off’ on their licence renewal. While locally there is no medical mandatory reporting, the potential for having to notify the Driver Licensing authority if they were aware a patient was still driving when they had assessed them as not being medically fit, or had subsequently been issued a licence renewal from another doctor was supported. Likewise, given the difficulties to detect functional deficits in a brief consultation with new patients and to address the problem of doctor-shopping, it was suggested that a system of record be put in place whereby doctors were able to be check who a new patient had visited previously, to ascertain the previous health professional’s judgement of their fitness to drive. However, a number of participants highlighted concerns for the privacy issues that would arise from such a register, and its effect on the right of a patient to seek a ‘second opinion’ of their medical fitness to drive.

Defining the point at which a patient should cease driving also served as an ethical concern for GPs. The majority of respondents did not support stopping someone from driving as soon as a diagnosis was given, in particular because this would deter most patients from coming back to see their GP for other health checks, or expressing any concerns regarding memory problems. GPs also did not support an arbitrary time point at which driving should stop, acknowledging that it was a matter of considering how variable the individual experience of dementia can be, and finding a balance between safety and unnecessarily depriving someone of transport and independence.

Discussion

The findings of this study highlight the complexities for GPs of managing driving cessation with patients with dementia in primary care settings. While respondents identified and implemented a number of workable strategies to facilitate transition to non-driving for their patients, many were very reluctant or did not know how to start the conversation. Community education and awareness about the impact of dementia on driving was identified as especially important for the person with dementia and their family members, to ensure acceptance of the decision to eventually cease driving. Future efforts in this area could focus on developing a user-informed approach to managing driving cessation in primary care, beginning with the perspectives expressed by persons with dementia who have transitioned to non-driving about how best to deliver the message.

Reluctance by health professionals to become involved in driving conversations and decisions and to have someone without a key role in patient’s care play the “villain” has arisen in other driving management research in several countries (Friedland et al., Reference Friedland, Rudman, Chipman and Steen2006; Hoggarth, Reference Hoggarth2013; Jang et al., Reference Jang2007; Johnson, Reference Johnson2000; Rapoport et al., Reference Rapoport2018). While many felt that final judgement of a patient’s fitness to drive should lie elsewhere, there was recognition that what may be lost in such a process would be the GP’s insights from their relationship with the patient, and the patient’s trust that is leveraged from the relationship. A compromise model such as that proposed by Fildes et al. (Reference Fildes, Charlton, Pronk, Langford, Oxley and Koppel2008) gives the relevant licensing authority principal responsibility for determining a patient’s fitness to drive, while the health professional assists in the referral and screening process; such a process may help to resolve these issues. Alternatively, working in combination with a GP within the practice or a nearby practice to conduct assessment, or to communicate a ‘second opinion’ of patients with dementia, may resolve the conflict somewhat.

A lack of screening and assessment measures suitable for indication of medical fitness to drive in the primary care setting has been identified in earlier research (Dickerson et al., Reference Dickerson2007; Molnar et al., Reference Molnar, Patel, Marshall, Man-Son-Hing and Wilson2006) and remains a current issue for GPs. While a number of off-road tests were being used, many of these are documented as lacking sensitivity and specificity in terms of identifying drivers who may be unsafe (Molnar et al., Reference Molnar, Patel, Marshall, Man-Son-Hing and Wilson2006; Rapoport et al., Reference Rapoport2018), however these were commonly in use due to lack of alternatives. It is difficult for GPs to explain their reasons for removing a licence, when the decision is made somewhat subjectively. Furthermore, identifying the critical time at which to begin the process of transitioning a patient to non-driving was even more challenging without the resources of objective measures and cut-off scores. Using memory tests alone, which are not validated against on-road driving performance, may impart the wrong message to patients that safe driving requires only memory. In the absence of a standardized approach to determine at-risk drivers, the GP might ideally employ a composite of behavioral and verbal measures, such as interview, reaction time, useful field of view, contrast sensitivity, etc.

The findings are consistent with prior studies showing that the process of managing driving cessation and fitness to drive altered long-standing relationships for physicians and their patients (Jang et al., Reference Jang2007; Rapoport et al., Reference Rapoport2018; Sims et al., Reference Sims, Rouse-Watson, Schattner, Beveridge and Jones2012). To preserve this relationship, GPs felt that it was better to have someone else make the difficult decision, for example another health professional within the practice such as a practice nurse, or external to the practice, such as a specialist driving assessor, occupational therapist, or optometrist.

Consistent with findings reported in studies from the UK, USA, Canada, NZ, Sweden, and Finland, GPs feel insufficiently trained to assess fitness to drive (Hakamies-Blomqvist et al., Reference Hakamies-Blomqvist, Henriksson, Falkmer, Lundberg and Braekhus2002; Hawley and Galbraith, Reference Hawley and Galbraith2008; Hoggarth, Reference Hoggarth2013; Jang et al., Reference Jang2007; Ott et al., Reference Ott2005; Perkinson et al., Reference Perkinson2005). GPs who reported lengthier experience described more proactive approaches to tackle the issues with their patients, and sooner rather than later. However, even for very experienced GPs, a paradox exists in finding a balance. That is, GPs are reluctant to act, to raise the issue of driving and stopping driving with patients, aware that preparation is key, but also aware of the devastating effect that removing a patient’s licence has on the individual and their family members, and consequently not wishing to upset what might be currently working for families. This paradox is consistent with previous findings (Adler, Reference Adler2010; Friedland et al., Reference Friedland, Rudman, Chipman and Steen2006; Jang et al., Reference Jang2007; Perkinson et al., Reference Perkinson2005; Sims et al., Reference Sims, Rouse-Watson, Schattner, Beveridge and Jones2012) and highlights a need for decision aids to assist GPs in making a difficult judgement.

Being aware of local transportation alternatives helped GPs facilitate the driving cessation conversation to some extent. Conversely having an awareness of limited local transportation alternatives made it harder to make an objective judgement about a patient’s driving cessation because the GP was acutely aware of the potential cost to their patient’s independence. Given constraints of time and resources, keeping up to date with relevant information, and highlighting alternatives to driving, might be outside of the scope of a GP’s practice, and could be managed by other community health professionals such as registered nurses (RNs), occupational therapists and psychologists. In addition, RNs working in GP practice settings could be trained to conduct assessment of driver fitness, and to discuss viable local transport alternatives with retiring drivers with dementia.

GPs acknowledged how distressing the process of transitioning a patient with dementia to non-driving status was for them, the individual and their family members. This is a common experience for a range of health care professionals who work with older persons around the issue of driving cessation across many countries (Dickerson, Reference Dickerson2014; Friedland and Rudman, Reference Friedland and Rudman2009; Jett et al., Reference Jett, Tappen and Rosselli2005; Johnson, Reference Johnson2000; Liddle et al., Reference Liddle, Bennett, Allen, Lie, Standen and Pachana2013). There was also an expressed hope, or what may be termed “wishful thinking,” that in future a cure for dementia will be found, or that with the introduction of driverless vehicles, the “problem” would cease to exist. While autonomous vehicles have the potential to prolong independent living and mobility for older adults, it has been acknowledged that there are numerous technical, ethical, and legal issues yet to be addressed before fully automated vehicles are the accepted standard mode of transport (Abraham et al., Reference Abraham2016; Musselwhite and Haddad, Reference Musselwhite and Haddad2007; Nunes et al., Reference Nunes, Reimer and Coughlin2018), in particular for people with special mobility needs. In addition, many older people with dementia who are told that they can no longer drive are vulnerable to a number of negative impacts (Pachana et al., Reference Pachana, Jetten, Gustafsson and Liddle2016), not just transportation.

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

The focus groups methodology was chosen for this exploratory study for several reasons, including that we wished to capitalize on the dynamic discussion between participants to explore the issues that they raised, and because GPs are very time poor in their professional practice. This methodology has its limitations, however, including the potential bias inherent in purposive sampling, and the extent of generalization given the limited number of participants possible in focus group studies. Consequently, our results should be interpreted with caution. A strength of our study was that we were able to include data from GPs from metropolitan and regional practices. However a limitation may be that we do not have data from practices that did not participate in the focus groups. To this end, future studies might look at deriving questions from the focus groups data to develop a comprehensive survey for widespread distribution to GPs. Future research might also look closer at the beliefs and attitudes that underlie practice discussions and behaviors in relation to driving cessation with patients with dementia and the interplay between GP factors and patient factors in constructing comprehensive models for understanding the transition process.

Conclusions

GPs may not wish to be in control of the process of evaluating capacity to continue driving, however the demands on them to deal with the issues and to assess fitness to drive appear to be growing with population ageing, not decreasing. These issues have relevance for practitioners in many other countries where similar system level issues exist, such as limited time and resourcing and no clear consensus on assessing medical fitness to drive. The challenges of managing this issue while universal may be approached differently depending upon cultural mores such as the degree of personal autonomy vs. family decision-making, and the cultural standing of older people (infallible/wise/not to be contradicted). Our findings suggest a need for community education and awareness around dementia and its effects on driving, reducing stigma around stopping driving, and aiding families to become proactively involved. Regarding identification and assessment of fitness to drive, upskilling GPs to start the conversation early and encourage their patients who are living with dementia to plan for the time when they will eventually cease driving is needed. Learning from these conversations with primary care practitioners can in turn inform the wider health care network to support best practice in clinical dementia care.

Conflict of interest

None.

Description of authors’ roles

T. Scott, J. Liddle, N. Pachana, E. Beattie, and G. Mitchell were involved in application for and achievement of funding, writing and editing the manuscript. T. Scott and G. Mitchell completed study design. T. Scott conducted focus groups. T. Scott, J. Liddle, and G. Mitchell completed data analysis. All authors contributed to revisions of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the Australian Research Council grant (# 1105924). The authors gratefully acknowledge the participants in this study and research staff member Donna Rooney for her assistance with analysis.