Introduction

The present study investigates bilingual children's sensitivity to phonological and semantic cues in the acquisition of grammatical gender assignment in German. The acquisition of gender by bilingual children has been extensively studied over the past few years, focussing on a number of language combinations and a variety of topics, including acceleration and delay compared to monolinguals (e.g., Eichler, Jansen & Müller, Reference Eichler, Jansen and Müller2013; Egger, Hulk & Tsimpli, Reference Egger, Hulk and Tsimpli2018; Hulk & van der Linden, Reference Hulk, van der Linden, Guijarro-Fuentes and Domínguez2010; Kaltsa, Tsimpli & Argyri, Reference Kaltsa, Tsimpli and Argyri2019; Kupisch & Klaschik, Reference Kupisch, Klaschik, Blom, Cornips and Schaeffer2017; Kupisch, Müller & Cantone, Reference Kupisch, Müller and Cantone2002; Rodina & Westergaard, Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015, Reference Rodina and Westergaard2017), age of onset effects (e.g., Granfeldt, Reference Granfeldt2018; Meisel, Reference Meisel2018); and the role of input and language use at home (e.g., Gathercole & Thomas, Reference Gathercole and Thomas2009; Montanari, Reference Montanari2014; Rodina & Westergaard, Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015, Reference Rodina and Westergaard2017). It has further been shown that early bilinguals, who typically have fewer occasions to use the minority language than monolinguals, are more likely to deviate from monolinguals in their performance on gender assignment than on gender agreement (Bianchi, Reference Bianchi2013; Granfeldt, Reference Granfeldt2018; Kupisch, Akpinar & Stöhr, Reference Kupisch, Akpinar and Stöhr2013; Ruberg, Reference Ruberg2013; Stöhr, Akpinar, Bianchi & Kupisch, Reference Stöhr, Akpinar, Bianchi, Kupisch, Braunmüller and Gabriel2012; Unsworth, Reference Unsworth2013). What remains unclear, however, is what mechanisms early bilingual children rely on when assigning gender and whether these differ from the assignment mechanisms found in monolingual acquisition. The present paper addresses this question based on data from German–Russian bilingual children.

When assigning gender, monolingual children have been argued to make use of formal cues from a relatively early age, often from the moment they start producing their first articles; see Karmiloff-Smith (Reference Karmiloff-Smith1979) for French; Bottari, Cipriani and Chilosi (Reference Bottari, Cipriani and Chilosi1993/94) for Italian; Kuchenbrandt (Reference Kuchenbrandt2005), Pérez-Pereira (Reference Pérez-Pereira1991) for Spanish; Rodina (Reference Rodina2007, Reference Rodina2008) and Rodina and Westergaard (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2012) for Russian; Demuth and Weschler (Reference Demuth and Weschler2012) for Sesotho. Marinis, Chondrogianni, Vasic, Weerman and Blom (Reference Marinis, Chondrogianni, Vasic, Weerman, Blom, Blom, Cornips and Schaeffer2017) have further shown that bilingual children make use of (morpho-)phonological cues when assigning gender not only when the target system is transparent (Greek), but also when it is opaque (Dutch) (see also Keij, Cornips, van Hout, Hulk & Emmerik (Reference Keij, Cornips, van Hout, Hulk and Emmerik2012) for older children acquiring Dutch).

Children's increased sensitivity to formal cues also obtains when natural gender cues are available. For instance, nouns ending in the nasal [ã] are typically masculine in French, and children acquiring French are found to (non-target-consistently) use the masculine article le even with the noun maman fem ‘mother’−a noun ending in a nasal – which exhibits the strongest possible semantic cue for feminine. In Karmiloff-Smith's (Reference Karmiloff-Smith1979) nonce-word experiment with mismatched phonological and semantic cues, e.g., deux bicrons (mas) with a picture of female creatures, children up to the age of 10 were found to predominantly use the phonological cue when assigning gender to these nouns. Young Russian-speaking children have also been found to occasionally produce feminine gender with masculine nouns ending in -a (the main cue for feminine nouns), such as papa ‘daddy’ (Gvozdev, Reference Gvozdev1961). Rodina (Reference Rodina2007) obtained similar results in an experimental study with the nonce word obormoša (fem) used to refer to an animal with clear masculine characteristics. Further, in a study on the acquisition of noun classes in the Northeast Caucasian language Tsez, Gagliardi and Lidz (Reference Gagliardi and Lidz2014) showed that children are biased to use phonological over semantic cues, although predictive semantic cues are more frequent in child-directed speech. Finally, artificial language learning experiments show that, compared to adults, children are biased to attend to formal rather than semantic cues, also in cases where the semantic cues are more reliable (Culbertson, Gagliardi & Smith, Reference Culbertson, Gagliardi and Smith2017; Culbertson, Jarvinen, Haggarty & Smith, Reference Culbertson, Jarvinen, Haggarty and Smith2019).

Crucially, evidence for the primacy of formal rules has so far been restricted to languages in which formal cues are relatively transparent, including Romance, Slavic and artificial languages. It is a matter of debate whether or not children acquiring German – a language with comparatively less formal transparency – also prioritize formal over semantic cues (cf. Mills, Reference Mills1986a,Reference Millsb; Szagun, Stumper, Sondag & Franik, Reference Szagun, Stumper, Sondag and Franik2007; Wegener, Reference Wegener1995). According to Slobin's (Reference Slobin, Ferguson and Slobin1973) Semantic Primacy Principle, paradigms are acquired early if there exist grammaticizable notions for grammatical regularities. For example, if the German definite articles der, die and das can be assigned based on the meaning of nouns, then semantic rules will be acquired before formal cues. Wegener's (Reference Wegener1995) study of L1 Polish, L1 Russian and L1 Turkish children acquiring German as an early L2 seems to confirm these ideas. Wegener finds overgeneralizations and metalinguistic comments in the children's spontaneous speech, indicating that they pay attention to semantic gender. She argues that only after having discovered semantic gender did the children start categorizing nouns into the three gender classes.Footnote 1 Similarly, in a study of pronoun use, Mills (Reference Mills1986a, p. 94) reports that the saliency of natural gender on animate nouns is high and competes with grammatical gender in the production of younger children (5–8 years). Mills (Reference Mills1986b) provides experimental data showing that German children at the age of 3–4 years produce gender-marked pronouns at a very high performance level on the basis of the natural gender rule, contradicting earlier claims by Levy (Reference Levy1983) that the natural-gender rule is late acquired. At the same time, evidence from naturalistic data suggests that German-learning children are sensitive to formal cues from a very early age, i.e., around 2 years (Szagun et al., Reference Szagun, Stumper, Sondag and Franik2007). Also in Russian, monolingual children have been found to acquire the semantic principles for gender assignment relatively early, in addition to their early preference for formal cues. Accuracy rates with semantic cues are well above 90% around age 3;6-4 (see Rodina, Reference Rodina2008; Rodina & Westergaard, Reference Rodina and Westergaard2012). This suggests that sensitivity to formal and semantic cues may go hand in hand.

In summary, although numerous studies have witnessed that young children rely heavily on formal cues when assigning gender, there is evidence that, at least in some languages, natural gender cues also play a role. For bilingual children, the issue is even more interesting, due to possible crosslinguistic influence (CLI) as well as reduced input and use of each of their languages compared to monolingual children. One goal of our study is therefore to investigate whether bilingual children are sensitive to phonological and semantic cues in the same way as monolingual children.

Background

Formal gender assignment systems come with different degrees of transparency across languages, and these different degrees are reflected in how fast children converge on adult-like assignment patterns. For example, Italian-learning children hardly make gender selection errors from the time they produce their first articles (e.g., Chini, Reference Chini1995; Kupisch et al., Reference Kupisch, Müller and Cantone2002), while Dutch-learning children continue make gender assignment errors until the age of seven (e.g., Blom, Polišenská & Unsworth, Reference Blom, Polišenská and Unsworth2008). Similarly, Spanish- and French-learning children appear to be sensitive to formal cues from early on, while children learning Norwegian, a language virtually without phonological cues, take considerably longer to produce gender-marking elements in a fully adult-like fashion. These observations are in line with the comparative transparency of formal assignment cues for gender marking: nouns in the Romance languages are often easily classifiable by means of their phonological endings (with French being less transparent than Italian, and Italian slightly less than Spanish), and the gender targets (e.g., articles and adjectives) often share these endings. Based on relevant research, both language acquisition studies (e.g., Szagun et al., Reference Szagun, Stumper, Sondag and Franik2007) and work on the validity of formal assignment cues (Köpcke, Reference Köpcke1982), we consider the German assignment system to be semi-transparent (see Figure 1 and below for more details).

Figure 1. Predictability of gender marking in selected languages.

We follow the cue-based approach to acquisition in Westergaard (Reference Westergaard2009, Reference Westergaard2014), which argues that children are sensitive to fine-grained distinctions in the input from early on (and not setting large-scale parameters). The cues – referred to as micro-cues in the model – are small pieces of morphosyntactic structure in the children's internalized grammar, showing how linguistic properties co-occur, e.g., a semantic feature or a particular ending on a noun corresponding with gender agreement on other targets such as determiners or adjectives.Footnote 2 Also relevant for our study is Bates and MacWhinney's (Reference Bates, MacWhinney, Bates and MacWhinney1989) Competition Model, a usage-based approach to acquisition with the notion of cue competition as its central concept. According to the model, cue strength is dependent on cue reliability and cue availability. Adults have been found to pay attention to cue reliability (e.g., in comprehension experiments), and this is also attested in older children (8–10 years), arguably because they have been sufficiently exposed to all cues by that age. However, at an early stage, children are predicted to be more influenced by cue availability than cue reliability (MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney, Kroll and De Groot2005), which resonates with Culbertson et al.'s (Reference Culbertson, Jarvinen, Haggarty and Smith2019) findings from artificial languages. We return to this issue below.

Gender marking in German

German has three genders, masculine, feminine and neuter. There is agreement marking on definite articles (e.g., der mas, die fem, das neu) and indefinite articles (e.g., ein mas/neu, eine fem) as well as on adjectives and various pronouns. However, interaction with number, case marking and definiteness as well as considerable syncretism in the paradigm make articles a somewhat unreliable indicator of gender (e.g., die is the plural article for all genders: die Katze fem ‘cat’, der Hund mas ‘dog’, das Kind neu ‘child’ but die Katzen fem ‘cats’, die Hunde mas ‘dogs’, die Kinder neu ‘children’).

The three genders are not distributed equally across nouns in the language. Neuter is the least frequent gender, while masculine has the highest frequency. For example, based on monomorphemic nouns in the CELEX corpus, Schiller and Caramazza (Reference Schiller and Caramazza2003, p. 171) established the following type-based frequencies: 19.2% neuter, 42.7% masculine, 38.1% feminine. However, the relative proportion of the three genders varies depending on corpus type; in some corpora that include basic vocabulary, masculine and feminine nouns are (almost) equally frequent (see Corteen, Reference Corteen2018, p. 41, for an overview of 10 corpus-based studies). Masculine is nevertheless considered the default gender for assignment because it is selected when no specific assignment rules apply, when assignment rules are in competition, or when loanwords are integrated into the language (Corteen, Reference Corteen2018; Steinmetz, Reference Steinmetz2006).

Köpcke (Reference Köpcke1982) has shown that there is a phonological basis for gender distribution in German, which can be described in terms of rules and regularities. Rules have no exceptions, e.g., noun compounds are assigned gender based on the gender of the last noun, e.g., Wein mas ‘wine’ + Flasche fem ‘bottle’ → Weinflasche fem. Regularities represent probabilistic tendencies that have exceptions, e.g., nouns in –e tend to be feminine, as in Flasche fem ‘bottle’; however, they can also be masculine, as in Hase mas‘hare’, or neuter, as in Auge neu‘eye’. The majority of phonological cues for gender assignment in German represent regularities, which means that they are reliable to different degrees. For instance, monosyllabic nouns with the onset cluster /ʃ/+C_ are associated with masculine gender 81% of the time, and monosyllabic nouns ending in _nasal+C are assigned masculine gender 70% of the time. According to the Consonant Cluster Principle (Köpcke, Reference Köpcke1982), the more consonants occur in the onset and coda of a monosyllabic noun, the more likely this noun is to have masculine gender. There are also considerable differences in the availability of these regularities, i.e., the number of nouns they apply to as well as the frequency of these nouns in the spoken language. For instance, 90% of disyllabic nouns ending in –e are feminine, and 95% of nouns ending in [ɛt] are neuter (Wegener, Reference Wegener1995, p. 93), but while there are numerous nouns ending in –e in German, only a handful of nouns end in [ɛt].

As for semantic cues, the natural gender rule determines that male human beings are masculine and females are feminine (Corbett, Reference Corbett1991; Köpcke & Zubin, Reference Köpcke, Zubin, Lang and Zifonun1996), although there are exceptions, e.g., Weib neu (old-fashioned word for) ‘woman’. In addition, male and female animate referents can be distinguished by means of certain suffixes, e.g., Lehrer mas-Lehrerin fem ‘teacher’, Krieger mas-Kriegerin fem ‘fighter’, although the rule is not entirely productive, e.g., Schuster mas-?Schusterin fem ‘shoemaker’. Furthermore, there are associations between particular semantic fields and a particular gender. For instance, colour terms are neuter; spices, large birds and alcoholic beverages tend to be masculine; sciences, musical instruments and insects tend to be feminine (Köpcke & Zubin, Reference Köpcke and Zubin1983). Experimental evidence has shown that these associations are part of native German speakers’ gender assignment systems (Schwichtenberg & Schiller, Reference Schwichtenberg and Schiller2004). Mills (Reference Mills1986a) provides examples that the natural gender rule also applies when German speakers choose nouns to refer to people: metaphorical terms used to refer to women tend to have feminine gender, e.g., die alte Schachtel fem /Schraube fem ‘the old box/screw’, die fleißige Biene fem ‘the diligent bee’, while those for men tend to have masculine gender, e.g., der alte Hund mas/Sack mas ‘the old dog/bag’, der schlaue Fuchs mas ‘the clever fox’. In the present study, we focus on the natural gender rule and disregard semantic fields.

In the acquisition of German, articles are the earliest gender targets occurring in child speech. Despite the complexities of the German article system, German children start using gender-marked articles very early, i.e., from around the second half of their second year (Szagun et al., Reference Szagun, Stumper, Sondag and Franik2007). Szagun et al. (Reference Szagun, Stumper, Sondag and Franik2007) show that error rates for gender marking decrease rapidly and drop below 10% by age 3;0. Based on diary data from monolingual children below age 4;0, Mills (Reference Mills and Slobin1985, pp. 155, 174–175) also reports that non-target production is rare; and, if errors are made, they typically involve the overuse of the feminine/plural article die. In an independent study with children aged 3;2-6;0, Mills (Reference Mills1986a, pp. 70–71) found evidence that they analyze phonological rules because a higher number of correct articles appears in the child data with nouns that are phonetically marked as feminine (i.e., disyllabic nouns ending in –e) than with feminine nouns that do not have this typical ending. Mills presents further experimental data from 7-to-8-year-olds, showing that the association of the –e ending with feminine gender (“schwa rule”) is the first rule to be learnt. Other rules are only acquired as the child's lexicon expands (p. 85), and the acquisition of gender is still in progress at the age of eight. This is at least partially contradictory to Szagun et al. (Reference Szagun, Stumper, Sondag and Franik2007), who found that even younger children (1;4 to 3;8) erred systematically in the direction of a rule or regularity, e.g., assigning masculine gender to feminine and neuter nouns that end in –el, -en, -er −endings typically associated with masculine. In terms of the three genders, most studies report earlier uses of feminine articles and late acquisition of neuter (cf. Binanzer, Reference Binanzer2017; Eichler et al., Reference Eichler, Jansen and Müller2013; Bittner, Reference Bittner2006; Müller, Reference Müller, Unterbeck, Rissanen, Nevalainen and Saari2000), but it is unclear whether this is due to the high token frequency and saliency of die or the reliability of feminine gender cues.

Several studies have investigated the acquisition of gender in German–Russian bilinguals. Dieser (Reference Dieser2009) compared German–Russian bilinguals in their two languages and found a higher amount of rule-based (cue-based) learning in Russian than in German, arguably because cues for gender assignment are more transparent in Russian. She specifically indicated that the children were sensitive to the schwa rule and the natural gender rule. Ruberg (Reference Ruberg2013) studied gender marking in German as an early L2 (L1s Polish, Russian and Turkish). The bilingual children in his study made use of morphophonological and semantic cues in the same way as monolingual children, as they assigned gender more often correctly to nouns following the schwa rule, to monosyllabic nouns (associated with masculine) and to nouns following the natural gender rule. In terms of assignment errors, both monolingual and bilingual children defaulted to masculine gender (monolinguals 76.9% and bilinguals 70.8% of the time). Thus, sensitivity to regularities and default assignment seem to co-exist. The L1 Turkish children did not seem to make use of cues to the same extent as the two other bilingual groups, possibly due to the absence of a gender system in Turkish (see also Wegener, Reference Wegener1995). Ruberg's study leaves open whether the children's sensitivity to phonological cues could be related to CLI, since the children's L1s differed.

Using eye-tracking, Lemmerth and Hopp (Reference Lemmerth and Hopp2018) demonstrated that simultaneous German–Russian bilingual children (age 8–9) can use gender marking on German articles or adjectives to anticipate upcoming nouns, regardless of gender congruency, i.e., whether or not the items share the same gender value in the two languages. However, successive bilingual children showed predictive gender processing only for lexically congruent nouns, arguably because L2 gender is first accessed through the L1 lexicon. This lexical congruency effect might be taken to imply that, although gender assignment is largely arbitrary, bilingual children, at least sequential bilinguals, create a link between the genders of individual nouns in their two languages, thus transferring lexical properties.

In summary, German-learning children, both monolingual and bilingual, have been shown to display early sensitivity to some phonological regularities as well as the natural gender rule, but it is not clear how systematic the children's knowledge is, how knowledge of phonological and semantic regularities interact and whether the nature of CLI is related to transfer of cues.

Gender assignment in Russian compared to German

Russian, the heritage language of the bilingual children investigated here, also has a three-way gender system with masculine, feminine and neuter, where masculine is argued to be the morphological default. Corbett (Reference Corbett1991) provides the following distribution of the three genders, calculated on the basis of a total of 33,952 nouns in dictionaries of modern Russian: masculine 46%, feminine 41%, and neuter 13%. While Russian does not have articles, gender surfaces as agreement on adjectives, possessives, demonstratives and verbs in the past tense. The gender system is highly transparent with three morphophonological cues that account for the vast majority of all nouns in the language: nouns ending in a consonant are typically masculine (e.g., sneg ‘snow’) and nouns ending in -a are most often feminine (e.g., luna ‘moon’), but when the final vowel is unstressed, it is pronounced as schwa (e.g., chashka ‘cup’). Nouns ending in -o are generally neuter (e.g., moloko ‘milk’); cf. Corbett (Reference Corbett1982, Reference Corbett1991) for further information on the Russian gender system. This means that formal assignment cues do not generally overlap with German, although there is a certain similarity between the two languages for nouns ending in schwa: such nouns are typically feminine in both German and Russian.

Semantic cues in Russian are very similar to those in German, because natural gender rules apply. As in German, there are derivational suffixes denoting professions for female referents like uchitel’ mas – uchitel'nica fem ‘teacher-F’, director mas – direktrissa fem ‘head (of school)-F’, avtor mas – avtorka fem ‘author’, although the masculine variants of these nouns can also be used. Furthermore, unlike German, Russian marks the natural gender of the speaker in certain contexts, e.g., on predicative adjectives, Ja golodnaja fem vs. Ja golodnyj mas ‘I'm hungry’, depending on whether the speaker is female or male. In certain noun classes, there can be a mismatch between the semantic and phonological cues, e.g., with hybrid or double gender nouns (see, e.g., Rodina, Reference Rodina2008). In these cases, there may be variation with respect to gender agreement, in accordance with the semantic hierarchy; i.e., the further away a target is from the noun, the more likely it is to have semantic agreement (Corbett, Reference Corbett1991).Footnote 3

Russian monolingual children have been shown to master the transparent gender system before age three, with a certain delay for the ambiguous noun classes (such as papa-type nouns mentioned above or nouns ending in a palatalized consonant, which may be either masculine of feminine); cf. e.g., Gvozdev (Reference Gvozdev1961), Rodina (Reference Rodina2008), and Rodina and Westergaard (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2012). Similar results have been found for bilingual children (speaking Russian as a heritage language) with sufficient and consistent input in Russian; see Mitrofanova, Rodina, Urek and Westergaard (Reference Mitrofanova, Rodina, Urek and Westergaard2018) and Rodina and Westergaard (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2017) for Norwegian–Russian children, and Schwartz, Minkov, Dieser, Protassova, Moin and Polinsky (Reference Schwartz, Minkov, Dieser, Protassova, Moin and Polinsky2015) for children learning Russian with English, German, Finnish or Hebrew as majority languages.

The similarities and differences between the German and Russian gender assignment systems and their acquisition are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Similarities and differences in gender assignment in Russian and German

Research questions

The literature review has shown that bilingual children display similarities as well as differences compared to monolingual children when acquiring grammatical gender. Differences are especially evident in gender assignment and might be a result of crosslinguistic influence (CLI) or simply less input and use. However, the precise mechanisms of CLI are not well understood. Does exposure to one language make children pay more (or less) attention to linguistically relevant evidence (cues for gender assignment) in the other language? What exactly do children pay attention to? In the present study, we compare sensitivity to phonological and semantic cues and discuss this in relation to CLI. More specifically, based on the properties of the German gender system and findings from the previous research outlined above, we formulate the following research questions:

-

RQ1: Do young children assign gender based on phonological and/or semantic cues in a language like German, where phonological cues are relatively non-transparent?

-

RQ2: Is there any evidence for CLI from Russian on the German gender system of bilingual German–Russian children?

Given previous findings on German, summarized above, we predict that German-learning children will be sensitive to both phonological and semantic cues (RQ1). We further predict that the children display differences in their ability to assign gender depending on cue-strength. This expectation is based on previous studies having attested earlier acquisition of more transparent gender systems. At the same time, even if the target language has very few reliable gender cues, children still show sensitivity to them (see, e.g., Marinis et al., Reference Marinis, Chondrogianni, Vasic, Weerman, Blom, Blom, Cornips and Schaeffer2017 for Dutch).

Regarding RQ2, it is possible that bilingual children are generally less sensitive to gender cues than their monolingual peers, or alternatively, more sensitive. Given indications in the literature that mastery of a more transparent system can speed up the acquisition of a less transparent system (e.g., Egger et al., Reference Egger, Hulk and Tsimpli2018; Kaltsa et al., Reference Kaltsa, Tsimpli and Argyri2019), we predict that the bilingual children will show increased sensitivity to formal cues in German as an effect of CLI, due to their experience with Russian, which has a system with more transparent cues. We further expect some sensitivity to natural gender cues, as this was also found in monolinguals, but no increased sensitivity as an effect of CLI because natural gender cues are equally present in Russian and German. Finally, there might even be transfer of phonological cues since both German and Russian have feminine nouns in [ə], a cue which is highly frequent. Based on these considerations, we designed an experiment involving nonce words and pictures of animate creatures with matching and mismatching phonological and semantic gender cues. In the next section, we describe the participants and methodology of the experiment.

Method

Participants

The participants were 45 German–Russian bilingual children, aged 4–11 years (mean age 6;8 years), who grew up in Singen or Stuttgart (Southern Germany). We included a relatively large age range because the bilingual children's language proficiency in German varied considerably. Two thirds of the bilingual children (n = 30) grew up with both parents speaking Russian at home, while a third (n = 15) had one German-speaking and one Russian-speaking parent. This means that age of onset to German varied (range 0–6 years, mean 2;1), with most children typically being first exposed to German at the age of three (when entering kindergarten). Nonetheless, there turned out to be no significant differences in the responses of bilinguals from families with one or two Russian-speaking parents.

Additionally, we tested 20 monolingual German-speaking children (age range 3–10 years, mean age 5;7). Note that the mean age of the monolingual children is lower than of the bilingual group. The reason for this is that we wanted to match the general proficiency of monolingual and bilingual children, and since most of the bilinguals were sequentially exposed to German, they had had comparably less exposure to German than the monolinguals.

Experiment

The experimental design was inspired by Karmiloff-Smith (Reference Karmiloff-Smith1979) and aimed at testing the relative impact of phonological vs. natural gender cues on nonce words. The phonological cues were based on Köpcke and Zubin (Reference Köpcke and Zubin1983) and selected on the basis of relative reliability. As our feminine phonological cue we selected disyllabic words in –e (associated with feminine gender 90% of the time, Wegener, Reference Wegener1995). The feminine stimuli were Bimpe, Brunke, Fruxe, Golme, Köke, Knumpe, Krumse, Puchte. Our masculine phonological cue was a combination of two tendencies for masculine gender, the onset cluster [ʃ]+C_ and the ending _nasal+C: Schnemp, Schränz, Schment, Schlömp, Schromp, Stinz, Spronk, Stönz. These stimuli represent Köpcke's (Reference Köpcke1982) Consonant Cluster Principle, and Köpcke and Zubin (Reference Köpcke and Zubin1983, p. 174) showed in an experiment that participants assigned masculine gender 78% of the time to a combination of the regularities /ʃ/+C_ and _nasal+C. In our experiment, we chose nonce words that formed no minimal pairs with existing words and piloted them with adults. In order to cue for natural gender, we designed images of friendly-looking monster-like creatures with attributes that biased them to masculine or feminine gender. Feminine monsters were mostly colored in red or pink and had ribbons, hearts, flowers or long eyelashes; male monsters were mostly colored in blue and they had baseball caps, moustaches or ties.

There were four experimental conditions with four stimuli in each condition. In two of the conditions (FF, MM), the phonological and the semantic cue were matched; in the other two conditions (FM, MF) there was a clash between the phonological and the semantic cue. The four conditions are illustrated in Table 2 with the first letter representing the phonological cue.

Table 2. Conditions

Procedure

Children listened to a story about Martians who came to earth to explore the territory and then returned to their spacecraft to fly back home. The children were introduced to the names of the creatures by means of a PowerPoint presentation, showing two monsters (one big, one small) on each slide. The pictures were also printed onto memory cards and the interior of the spacecraft was printed on cardboard, so that, throughout the experiment, the children could select the respective memory cards and put them onto the seats of the spacecraft. The children were asked to help the Martians find seats, making sure that boys would sit next to boys and girls next to girls. This was done to raise awareness of their natural genders. When everyone was seated, the children were asked to tell the experimenter which of the Martians were boys and which were girls in order to ensure that they had perceived the natural gender cue. The children never failed to identify the intended gender (though occasionally pointing out that the creature was an Opa ‘grandfather’ rather than a boy).

When introducing the Martians, the experimenter used the terms ‘Martians’ and ‘monsters’ as well as ‘creatures with Martian-like/monster-like features’, in order to avoid the use of singular articles. This was done to preclude a gender bias in the pre-experimental phase – the German noun for monster (Monster) has neuter gender and the noun for Martian (Marsmensch) is masculine. Care was also taken to vary between the question word Was ‘what’ (a gender-neutral question word to refer to objects and things) and Wer ‘who’ (a question pronoun to refer to persons). The standard discourse for an individual trial is given in (1) (relevant genders are indicated and elements of interest highlighted). As the example shows, this procedure would elicit two indefinite DPs and one definite DP. The experimenters were native speakers of German, and they were carefully trained to ensure consistency in the experimental procedure.

(1) Experimenter: Was du hier siehst, heißt Krumse. Was siehst du?

‘What you see here is called Krumse. What do you see?’

Child: Einefem großefem Krumse und einefem kleinefem Krumse.

‘A big Krumse and a small Krumse’

Experimenter: Und wer ist verschwunden und sitzt in der Rakete?

‘And who has disappeared and sits in the spacecraft?’

Child: Diefem kleine Krumse.

‘The small Krumse.’

Analysis

Each child response was coded in terms of the assigned gender based on the three realizations (see example 1). In the definite condition, the article indicates the assigned gender, while the adjective form does not differ across genders; cf. der mas rote Spronk, die fem rote Krumse, das neu rote Stönz ‘the big X’. In the indefinite condition, the combination of article and adjective indicates the assigned gender, since the indefinite article alone is insufficient to tease apart masculine and neuter; cf. einmas/neu großer mas Spronk ‘a big spronk’, einefem große fem Krumse ‘a big krumse’, einmas/neu großes neu Stönz ‘a big stönz’. We excluded DPs in which the nouns were changed, unless the cue had been retained; e.g., Stönz as Stenz was included, but Puchte as Pucht was excluded. Moreover, we excluded the following cases, as it is unclear which gender had been assigned, or whether any gender had been assigned at all:

(i) DPs in which gender marking was inconsistent between the article and the adjective, e.g., eine fem grünes neu Fruxe ‘a green fruxe’;

(ii) DPs with omitted articles and/or uninflected adjectives;Footnote 4

(iii) Instances of inconsistent gender assignment over the three elicited DPs (e.g., eine fem grüne Fruxe-der mas grüne Fruxe);

Inconsistent gender assignment of the type in (iii) occurred 14% of the time in both groups, while the bilinguals omitted articles more frequently (28%) than monolinguals (15%).Footnote 5

Results

Monolingual children

Figure 2 illustrates gender agreement by condition in the monolingual group. Here and in the following figures, the gender-clash conditions (FM, MF) are represented by the columns in the middle, and the congruent conditions (FF, MM) by the leftmost and rightmost columns, respectively. The phonological cue is represented by the first letter in the name of the condition, the natural gender cue by the second letter.

Figure 2. Monolingual children, gender assignment by condition.

Going from FF to MM (left to right in Figure 2), the proportion of feminine gender decreases, and the proportion of M increases, which indicates that both types of cues might play a role. When phonological and semantic cues coincide (FF and MM), the target gender is cued more strongly compared to the conditions where the two types of cues clash (FM and MF). A visual comparison of the FM vs. MF conditions indicates that the phonological cue is stronger than the natural gender cue (29% vs. 19% F, and 29% vs. 36% M, respectively). When we compare the MF with the MM condition and the FF with the FM condition, we see that the natural gender cue might also have an effect (masculine is used more in the FM than in the FF condition, and feminine is used more in the MF than in the MM condition). Furthermore, there is a considerable proportion of neuter responses in all conditions.

The high proportion of neuter responses was quite unexpected because the experimental items provided neither semantic nor phonological cues for neuter gender. We therefore suspected that some children might have picked up a cue for neuter in the instructions or used neuter by default. If this were the case, we would expect the proportion of neuter assignment to be unevenly distributed across the monolingual participants, predominating in some of the children. Indeed, when we looked at the proportion of neuter used by individual participants, a clear pattern emerged: half of the children (n = 10) almost never used neuter (overall less than 10%), and half of the children (n = 10) used neuter in 50% or more of their responses. In the latter group, 6 children used neuter 80–100% of the time, while 4 children used it between 50 and 70% of the time. We therefore divided the children into groups of “neuter-defaulters” (assigning neuter 50% or more) and “non-neuter-defaulters” (assigning neuter less than 10%). The two groups were equal in size (n = 10), with the defaulters being overall around 1;5 years older than the non-defaulters (mean age 6;5 vs. 5;0 years). Figures 3a and 3b make it evident that the children in the neuter-defaulter group (Figure 3a) used neuter gender almost exclusively, while non-defaulters (Figure 3b) hardly ever used it, confirming the above prediction. Note that in both groups, we still see the step-wise increase in masculine gender across the four conditions.

Figure 3a. Monolingual children with overall >50% neuter responses (n = 10): Gender used across conditions.

Figure 3b. Monolingual children with overall <10% neuter responses (n = 10). Gender used across conditions.

Bilingual children

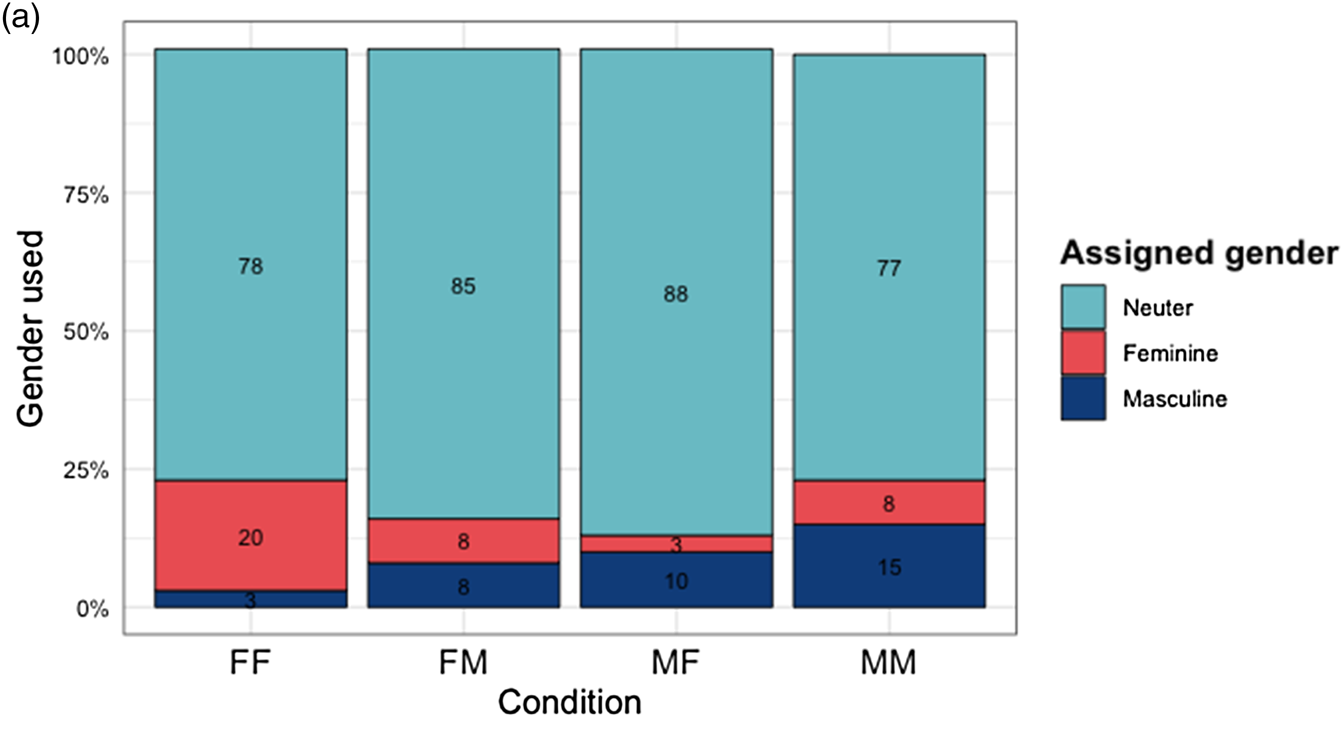

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of responses across the four experimental conditions in the bilingual data.

Figure 4. Bilingual children, gender assignment by condition

The figure shows that the bilingual children use neuter rarely (especially in the FF and FM conditions), thus behaving like the group of (younger) monolinguals who did not default to neuter (see Figure 3b). The results further show that the bilinguals use more feminine than masculine overall. As in the monolingual group(s), the proportion of assigned feminine decreases and the proportion of masculine increases from left to right (FF to MM), indicating cue sensitivity.

Statistical analysis

To maintain the possibility of a binomial test, we fit three generalized linear mixed effects models to predict the probability of using masculine, feminine and neuter. ANOVA model comparison was applied to choose the winning model. In the final analysis, the probability of using masculine (model 1), feminine (model 2) and neuter (model 3) was estimated based on two predictors: condition (FF, FM, MF and MM) and group (bilinguals vs. monolinguals), and their interaction. Model comparison revealed that including age (continuous) as a fixed effect did not significantly improve model fit for any of the three modelsFootnote 6. The variables were dummy-coded, and participants and items were included as random intercepts. To estimate the contrasts between individual groups within conditions and individual conditions within groups, we additionally ran post-hoc pairwise comparisons for each model. All generalized linear mixed effects models were fit using the lme4 package (Bates, Maechler, Bolker & Walker, Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015) of the software R version 4.0.2. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were run using the R package emmeans (Lenth, Singman, Love, Buerkner & Herve, Reference Lenth, Singman, Love, Buerkner and Herve2020) with adjusted alpha levels (Tukey's method to control for multiple comparisons).

Model 1 predicted the use of masculine as an interaction of two fixed effects, condition and group (see Table A1 in the Appendix, Supplementary Materials). The analysis did not reveal any significant differences between the mono- and bilinguals in the use of masculine. The effect of group was not significant, and there were no significant interactions of condition and group. Pairwise comparisons of groups within conditions with adjusted alpha-levels yielded the following results: in the FF condition p = 0.33, the FM condition p = 0.5, in the MF condition p = 0.75, and in the MM condition p = 0.8 (see Table A2 in the Appendix, Supplementary Materials). At the same time, the results revealed a significant effect of condition. The probability of using masculine was significantly lower in the FF condition when compared to the FM (p = 0.04), MF (p < 0.001) and MM (p < 0.001) conditions. Pairwise comparisons of conditions within groups revealed a similar pattern in both groups. There were significant contrasts in the use of masculine between the FF and MF conditions (p = 0.001 for the bilinguals and p = 0.04 for the monolinguals), between the FF and MM conditions (p < 0.001 for both groups) and between the FM and MF conditions (p = 0.001 for the bilinguals and p = 0.02 for the monolinguals). No other contrasts were significant (see Table A3 in the Appendix, Supplementary Materials). This result confirms a significant effect of the phonological cue for both mono- and bilinguals, whereas the effect of the natural gender cue was not statistically significant (no significant differences were observed within individual groups between conditions that differed only in the natural gender cue, i.e., FF vs. FM and MF vs. MM).

The results of model 2 that predicted the use of feminine as an interaction of two fixed effects, condition and group are illustrated in Table B1 in the Appendix (Supplementary Materials). The results show that the bilinguals were significantly more likely to use feminine than the monolinguals overall (p < 0.001) and in individual conditions (p < 0.001) for each of the four conditions, as indicated by post-hoc pairwise comparisons of groups within conditions (see Table B2 in the Supplementary Materials), suggesting a general preference for feminine in the bilinguals. At the same time, the results also revealed cue-sensitive behavior in both groups (see Table B3 in the Supplementary Materials). Feminine was used significantly more often in the FF than in MF and MM conditions by both groups (p < 0.001 in both pairwise comparisons for the bilinguals, and p = 0.02 and p < 0.001 for the monolinguals). Moreover, participants from both groups were significantly more likely to use feminine in the FM than in the MM condition (p < 0.001 for the bilinguals and p = 0.04 for the monolinguals). Finally, bilinguals were significantly more likely to use feminine in the FM than in the MF condition (p = 0.001). This again shows strong sensitivity to the feminine phonological cue by both bilinguals and monolinguals. The effect of the natural gender cue on the use of feminine was less pronounced (for both groups the contrasts between the FF and FM conditions, and between the MF and the MM conditions were not significant).

Finally, the results of model 3 that predicted the probability of neuter use based on an interaction of two fixed effects, condition and group, are illustrated in Table C1 in the Appendix (Supplementary Materials). The analysis revealed that monolinguals were significantly more likely to use neuter overall (p < 0.001) and in individual conditions (p < 0.01 for each of the four conditions, as indicated by the post-hoc pairwise comparisons; see Table C2 in the Appendix, Supplementary Materials). There were no differences in the use of neuter between individual conditions for the monolinguals (see Table C3 in the Supplementary Materials). At the same time, bilingual children used significantly less neuter in all conditions with the feminine phonological cue, as compared to conditions with the masculine cue (FF vs. MF p = 0.003; FM vs. MF and FM vs. MM p < 0.001). No other contrasts were significant.

In summary, we found a significant effect of phonological cues for both groups and a numerical trend for natural gender cues. Moreover, both monolingual and bilingual children were most successful in assigning feminine gender when nouns had a feminine phonological and/or natural cue, and least successful when nouns had the respective masculine cues. Recall that the phonological masculine cue in our experiment had a weaker cue reliability than the feminine cue. In this respect, the children's behavior is consistent with the reported cue strength for phonological regularities in German.

Discussion

We set out to explore two questions related to cue sensitivity in the German of monolingual and bilingual (German–Russian) children, repeated here:

RQ1: Do young children assign gender based on phonological and/or semantic cues in a language like German, where phonological cues are relatively non-transparent?

RQ2: Is there any explicit evidence for CLI from Russian on the German gender system of bilingual German–Russian children?

Sensitivity to phonological and semantic cues in mono- and bilingual German

With respect to cue sensitivity in German (RQ1), we found a significant effect of the phonological cues for both groups and only a numerical trend for the natural gender cues. This suggests that both monolingual and bilingual children are more inclined to pay attention to phonological cues than to natural gender cues, replicating findings from previous studies of monolinguals learning other languages, e.g., Karmiloff-Smith (Reference Karmiloff-Smith1979), Rodina (Reference Rodina2007), Szagun et al. (Reference Szagun, Stumper, Sondag and Franik2007), Gagliardi and Lidz (Reference Gagliardi and Lidz2014) and Culbertson et al. (Reference Culbertson, Gagliardi and Smith2017, Reference Culbertson, Jarvinen, Haggarty and Smith2019). This is the case even though phonological cues in German have a relatively low reliability. Although not significant, the numerical tendency for the semantic cue to increase performance lends weak support to earlier claims by Mills (Reference Mills1986a,Reference Millsb) and Müller (Reference Müller, Unterbeck, Rissanen, Nevalainen and Saari2000), suggesting that children pay attention to both formal and semantic gender cues. By contrast, our results are inconsistent with the Semantic Primacy Principle and the idea that the acquisition of semantic rules in German is a precondition for the formal classification of nouns into the three gender classes, as proposed by Wegener (Reference Wegener1995). More generally, our data raise the question why all children showed comparatively little sensitivity to natural gender cues, though clearly recognizing what sex the depicted animate objects had.

The answer to this presumably lies in the relative cue strength of phonology vs. semantics, more specifically the distinction between cue availability and cue reliability. As argued by MacWhinney (Reference MacWhinney, Kroll and De Groot2005), young children, who have been exposed to considerably less input than adults, should be paying attention to the more available cues first. Only around the age of 8–10 would children's preferences be similar to those of adults, as all relevant cues should have been sufficiently encountered in the input by then. The ubiquitous nature of phonological cues would thus explain why young children tend to choose phonological over semantic cues when assigning noun class gender. Culbertson et al. (Reference Culbertson, Jarvinen, Haggarty and Smith2019) have also attested that early availability is an important factor, as adults exposed to semantic before phonological cues in an artificial language learning experiment more or less consistently preferred the semantic cue. A similar effect was found for children; i.e., early exposure to semantic cues increased the likelihood of children preferring these cues. But experimental contexts where phonological cues were available first were no different from contexts where the two types of cues were presented simultaneously. This indicates that early availability is not the full answer and that young children generally have a higher sensitivity to phonological than semantic cues, beyond the early availability of the former in the input. Although we did not include early vs. late availability as a factor in our study, our findings from nonce words in a real natural language clearly mirror the experimental effects found in Culbertson et al. (Reference Culbertson, Jarvinen, Haggarty and Smith2019): German-speaking children display a high sensitivity to phonological cues, even when these cues are unreliable, while semantics plays a relatively minor role.

While we found that both groups of children were sensitive to phonological cues, with no differences in the use of masculine across the mono- and bilingual children, the two groups showed an unexpected difference in their defaulting strategies: while the monolinguals defaulted to neuter, the bilinguals were more likely to use feminine across all conditions. We discuss possible explanations for this in the next section, some of which we will exclude.

With respect to RQ2, there are several ways in which Russian could have influenced the bilinguals’ performance in German. One way is in their treatment of the feminine cue, i.e., the schwa ending. Recall that Russian nouns ending in schwa tend to be feminine, which corresponds with the feminine cue we used in our German experiment. Bilinguals show clear sensitivity to the schwa ending, which manifests itself in significantly higher proportions of feminine assigned in conditions with this cue, as compared to conditions with the masculine phonological cue. Thus, cross-linguistic cue influence seems plausible. However, it would not account for the overuse of feminine in conditions with the masculine phonological cue. The children in our sample participated in similar experiments on Russian gender and were found to be more advanced in their acquisition of gender cues in their heritage language. If their behaviour were primarily guided by transferring cue knowledge from Russian, we would have expected them to refrain from overusing feminine with consonant-final nouns, which are masculine in Russian and also in our German test items. We therefore suspect that the use of feminine in conditions with the masculine phonological cue might be an artefact of self-priming. At the same time, our results show that the bilingual children used significantly less neuter in conditions with the feminine phonological cue as compared to conditions with the masculine phonological cue, suggesting that they are sensitive to the absence of the feminine cue as well. Therefore, it remains difficult to tease apart possible cue transfer from defaulting to feminine as an unmarked form, as we discuss in the next section.

Unexpected defaulting strategies

Since masculine is considered to be the default for gender assignment in both Russian and German (Corbett, Reference Corbett1991; Steinmetz, Reference Steinmetz2006), the fact that monolinguals defaulted to neuter and bilinguals to feminine is entirely unexpected.

For the monolingual children's defaulting behavior, we see two possible explanations, both related to potential cues in the instruction. One possible explanation is related to the nouns used to introduce the animate objects, i.e., Marsmensch mas ‘Martian’ and Monster neu ‘monster’, which were both used. From a semantic perspective, children might have assigned neuter because they perceived ‘Martians’ or ‘monsters’ as having no biological gender, while from a grammatical perspective, they could have retrieved the gender of Monster neu ‘monster’, although the noun was introduced in the plural, where gender is not marked. However, all the children correctly classified the Martians into girls and boys, suggesting that the intended natural gender was obvious to them. We also ran another experiment with nonce words with the same monolingual children, where no possible semantic cues for neuter gender were provided, and the monolingual children nevertheless defaulted to neuter. Yet another possible explanation could be that the children associated the question pronoun Was ‘what’ with neuter (when we asked Was siehst Du? ‘What do you see?’), interpreting it as a “syntactic” target linked to the name of the depicted object. The question pronoun Was is not specifically marked for neuter gender (it is the pronoun asking for things as opposed to persons), but it has the –s ending that is typical of neuter forms, e.g., das (definite article, neuter), rotes (adjective, neuter), eines (indefinite article, neuter/masculine, genitive case). It has indeed been proposed for German that while masculine gender is the default for gender assignment, neuter gender might be the default on the sentential level (Köpcke & Zubin, Reference Köpcke, Zubin, Hentschel and Vogel2009, p. 148ff; Corbett & Fraser, Reference Corbett, Fraser, Unterbeck and Rissanen2000, p. 69f). Of course, if this explanation is on the right track, it raises the question why only the monolinguals but not the bilingual children interpreted Was as a cue for neuter, although the instruction was the same for them. One possible explanation is that sensitivity to structural cues increases only gradually with age (cf. Mills, Reference Mills1986a; Karmiloff-Smith, Reference Karmiloff-Smith1979). This is plausible, considering that with more experience in languages like French and German, children will realize that there are many exceptions to phonological cues, while syntactic cues are very reliable. In our data set, it was indeed the older children that were more inclined to default to neuter gender. The bilingual children in our study were older than the monolingual controls, but they had had less exposure to German and were therefore potentially less sensitive to this type of cue than the older monolingual children.

With respect to the defaulting to feminine gender in the bilingual group, one possible explanation is the frequency of the form die ‘the’ in the input (recall that it is the plural form for all genders), which may have resulted in the bilinguals overusing this form. However, we think that this explanation is weakened on the grounds that bilinguals also overused the indefinite article eine, which is less frequent than its masculine/neuter counterpart ein. In other words, if the overuse of feminine gender in our data were due to the token frequency of the article die, we would have expected an analogous overuse of the masculine/neuter indefinite article ein. Recall that we elicited two instances of indefinite DPs and one definite DP in our experiment; see example (1). When we looked for inconsistently assigned gender across the three realizations, we found very few switches (n = 41), and switches from ein mas to die fem (n = 20) were as frequent as from eine fem to der mas. If the behaviour of the bilingual children were simply due to frequency, we would have expected more switches of the former type, since ein and die are the most frequent article forms.

A second possible explanation is the existence of surface rhyming between the indefinite feminine article eine, the adjective in the feminine condition, and nouns ending in schwa, e.g., eine fem kleine fem Puchte (fem) ‘a small Puchte’, which might have affected younger children, who are known to be very sensitive to phonological properties when acquiring morphology (e.g., Bottari et al., Reference Bottari, Cipriani and Chilosi1993/94). However, a factor that speaks against surface rhyming as (the sole) explanation is that the children also overused the feminine on definite DPs, where the article does not end in the same vowel as the adjective and noun (e.g., die fem [diː] rote fem Fruxe (fem) ‘the red Fruxe’).

A third possible explanation is self-priming in combination with high sensitivity to the formal cue: the feminine gender cue we used in our experiment covers a large range of nouns and is extremely reliable. Like the monolinguals, the bilingual children are aware of this highly reliable cue, and it is plausible that they also acquire it prior to other cues, as suggested by Mills (Reference Mills1986a). However, this raises the question, discussed above, why the children used feminine also in the absence of the cue. We suspect that overuse of feminine (where it is not cued) might be related to priming: the children were primed by their own responses when they knew which gender should be used and tended to use the same gender in situations where they were unsure.

A final possible explanation involves the feminine as the unmarked form: in indefinite DPs, the strong declension of a feminine adjective ends in -e (e.g., eine fem kleine fem X ‘a small X’), and this could be said to be unmarked in comparison with masculine -er and neuter -es (ein kleiner mas X, ein kleines neu X ‘a small X’). Thus, when children are unsure of the gender of a noun, they may simply default to the unmarked form, producing a schwa as a placeholder for a gender exponent. This unmarked form of the adjective also corresponds to the adjective form in the weak declension, which is found with all genders in the nominative (der mas/die fem/das neu kleine X ‘the small X’), making this the most frequent adjective form. Based on the available evidence, we cannot tease apart the four alternative explanations, and it is possible that they are jointly at play, but for the aforementioned reasons we consider the latter two most plausible.

Conclusion

Bilingual German–Russian children are sensitive to gender assignment cues in the same way as monolingual children, showing priority of phonological over natural gender cues. There is no evidence that the simultaneous exposure to Russian slows down the acquisition of gender assignment in German. Although it is plausible that the children develop increased awareness to phonological cues in German owing to their knowledge of Russian, it is difficult to tease apart cue transfer from other potentially interfering factors, especially self-priming and overuse of an unmarked form.

Supplementary Material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000921000039

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Miriam Geiss, Nadine Kolb, Ksenia Mack and Simone Waitz for invaluable help in collecting the data. This research was supported by a grant from the Research Council of Norway for the project Microvariation in Multilingual Acquisition & Attrition Situations (MiMS), project code 250857. The paper was completed while the authors were fellows at the Centre for Advanced Study at the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters in Oslo during the academic year 2019–2020, working on the research project MultiGender.