1. INTRODUCTION

Theoretical studies in linguistics and pragmatics have suggested that some French verbal tenses have standard or temporal (also referential) usages on the one hand and non-standard or perspectival (also subjective) usages on the other;Footnote 1 in the latter case, they do not express their regular temporal reference (for example, past time for the Passé Simple (PS), the Passé Composé (PC) and the Imparfait (IMP)) but “imply a change in the perspective from which the eventuality can be grasped” (Saussure, Reference de Saussure, Jaszczolt and de Saussure2013: 46). For example, in the PS in (1), the reader has access to the character’s (Julien) thought; the apparent semantic incompatibility between the adverbial and the verbal tense is solved by perspective-taking.Footnote 2

-

(1) Le malheur diminue l’esprit. Notre héros eut la gaucherie de s’arrêter auprès de cette petite chaise de paille, qui jadis avait été le témoin de triomphes si brillants. Aujourd’hui, personne ne lui adressa la parole ; sa présence était comme inaperçue et pire encore. (Vuillaume, Reference Vuillaume1990 from Stendhal’s Le rouge et le noir),

‘Our hero had the awkwardness of stopping near this little straw chair, which once had witnessed such brilliant triumphs. Today, no one talked to him; his presence was unnoticed and even worse.’

According to Vuillaume, readers who read this type of sentence have the feeling both of being aware of a past event and of witnessing it at the very moment it takes place (Reference Vuillaume1990: 10). The first aspect of this dual understanding is due to the PS, while the second is due to the adverbial aujourd’hui. This is a typical example of a perspectival usage of a verbal tense. Perspective-taking, a phenomenon involved in this type of usage of a verbal tense, refers to the mechanisms by which language comprehenders take into account what another person knows, feels, thinks or believes. Perspective-taking is known to be one of the components of speaker’sFootnote 3 subjectivity, which may be defined as “the expression of self and the representation of a speaker’s (or, more generally, a locutionary agent’s) perspective or point of view in discourse – what has generally been called a speaker’s imprint” (Finegan, Reference Finegan, Stein and Wright1995: 1). Lyons (Reference Lyons, Jarvella and Klein1982) characterizes subjectivity as “the way in which natural languages, in their structure and their normal manner of operation, provide for the locutionary agent’s expression of himself and of his attitudes and beliefs” (p. 102), and he emphasizes that a speaker’s expression of self goes beyond “the assertion of a set of propositions” (p. 104). As highlighted by Finegan (Reference Finegan, Stein and Wright1995: 4), to investigate subjectivity, studies focused on three individual fields: a speaker’s perspective and perspective-taking (Langacker, Reference Langacker1990), a speaker’s expression of affect towards the propositions contained in utterances via the lexicon and grammar (Besnier, 1990), and a speaker’s expression of the modality or epistemic status of the propositions contained in utterances (Lyons, Reference Lyons, Jarvella and Klein1982). Nonetheless, subjectivity is a notion of “near ineffability” (Langacker, Reference Langacker1990: 34) and rare are the studies that approached it as a whole or its components empirically or experimentally.

In this study, we use experimental methods to investigate whether French verbal tenses, via perspective-taking, give access to speaker’s subjectivity, by which we understand the expression of the speaker’s personal point of view or perspective, her evaluation of a certain situation, her emotions and her psychological states. Thus, an utterance may be perceived as subjective, when it contains one or more subjectivity triggering elements, or an objective, when it does not contain any subjectivity triggering elements. Consequently, our research question in this article is whether verbal tenses are subjectivity – precisely, speaker’s point of view or perspective – triggering elements. We build on the assumption that perspective-taking is a component of speaker’s subjectivity (cf. Finegan, Reference Finegan, Stein and Wright1995) to test empirically whether annotators can identify the subjective usages of the PC, PS and IMP in corpus data (Study 1), and to test experimentally whether language users rely on subjectivity when they process the perspectival usage of the PS illustrated in example (1) (Study 2). In particular, in Study 1 we use an annotation task of two sets of corpus data: one in which annotators have access to the target verbal tense, and one in which we concealed the verbal tense. The annotators’ task was to categorise those corpus excerpts as subjective or non-subjective (objective). Our hypothesis was that if verbal tenses, via perspective-taking, express the speaker’s subjectivity, then there will be significant differences in how annotators categorise the corpus excerpts as subjective or objective. In Study 2, a self-paced reading experiment, we focus on the perspectival usage of the PS illustrated in (1), and test how native speakers of French process sentences with a perspectival PS when preceded by a subjective or objective context.

Our article is structured as follows. In section 2, we review the literature most relevant to our research question. In sections 3 and 4, we present our experimental studies. We discuss the results and draw conclusions in section 5.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Benveniste (Reference Benveniste1966) laid the foundations of the linguistic study of subjectivity by saying that the speaker is the centre of the communicative act, and languages are organised around the speaker: the first-person pronoun I, and the speaker’s now and here. With respect to speaker’s now, Benveniste argues that some verbal tenses (the simple past) should be excluded from subjective discourses, where others (the present, the past compound and the future) should not be used in objective discourses. However, other studies have argued that this claim is too strong (e.g. Banfield, Reference Banfield1982; Fleischmann, Reference Fleischman1990; Sthioul, Reference Sthioul, Moeschler, Jayez, Luscher, de Saussure and Sthioul1998, Reference Sthioul2000; Tahara, 2000; Reference Tahara2004; Saussure, Reference de Saussure, Jaszczolt and de Saussure2013; Moeschler, Reference Moeschler and Pavelin Lesic2014; Reference Moeschler2019), and that verbal tenses occurring in the non-prototypical type of discourse provide access to the speaker’s perspective. The question of the link between verbal tenses and speaker’s subjectivity has been widely debated from a variety of approaches. In this work, we focus on those carried out in literary criticism, for which the perspectival usages of verbal tenses are linked to the Free Indirect Discourse (FID),Footnote 4 and those within a linguistic and pragmatic framework, for which verbal tenses may have perspectival usages independently of FID.

Studies in literary criticism have drawn on the distinction between an experiencing self and a narrating self, illustrated by the pair of examples in (2) and (3). The difference between the PS in (2) and the IMP in (3) manifests in the objective character of the description of the seeing of the moon (with the PS) provided by a narrating self, compared to the subjective character of the description of the same event as experienced at a certain moment by an experiencing self (with the IMP) (Banfield, Reference Banfield1982; Fleischman, Reference Fleischman1990, Reference Fleischman, Fleischman and Waugh1991).

-

(2) Elle vit la lune.

‘She saw the moon.’

-

(3) Elle voyait la lune (maintenant).

‘She saw the moon (was seeing the moon now).’

For Banfield (Reference Banfield1982), in FID (containing represented speech and thought), sentences with the IMP are subjective and they integrate the consciousness of an experiencing character within the description of a series of situations. They express, thus, an individual’s evaluations, emotions, judgments, uncertainties, beliefs and attitudes. As Fleischman (Reference Fleischman1990) puts it, the simple past is non-experiential and entirely detached from the speaker. Nevertheless (as we will discuss below), scholars (Reboul, Reference Reboul1992; Vuillaume, Reference Vuillaume1990; Tahara, Reference Tahara2000) pointed out that verbal tenses may have subjective usages in discourse types that are not FID, such as in (4). In the following fragment, the italicized verbs are in the PS and they express the advancement of time seen from Emma’s point of view (she was terrified and exhausted). The last verb, étouffaient, which is in the IMP, completes the description of Emma’s subjective perceptions and feelings.

-

(4) – Monsieur vous attend, madame, la soupe est servie. Et il fallut descendre! Il fallut se mettre à table! Elle essaya de manger. Les morceaux l’étouffaient. (Flaubert, Madame Bovary)

‘– Sir (Charles) is waiting for you, madam; the soup is served. And she had to go downstairs! She had to sit to the table! She tried to eat. The bites of food suffocated her.’

In linguistics, to explain the difference between the IMP and the PS, two types of accounts have been put forward: the semantic approach to the contextual values of verbal tenses (such as Desclés, Reference Desclés1990, Reference Desclés2017; Gosselin, Reference Gosselin1996, Reference Gosselin2005) and the perspective-taking approach (point de vue in French) to grammatical aspect (Comrie, Reference Comrie1976; Caenepeel, Reference Caenepeel1989; Fleischman, Reference Fleischman, Fleischman and Waugh1991, Reference Fleischman, Bybee and Fleischman1995; Smith, Reference Smith1991). In the first type of account, Desclés’ (Reference Desclés1990, Reference Desclés2017) semantic model provides fine-grained aspectual and temporal distinctions to describe the semantics of French verbal tenses and their contextual values (“effets de sens”). According to Desclés’ model, the semantics of the PC, PS and IMP needs to be described using the following components: lexical aspect (states, events and processes; cf. also Mourelatos, Reference Mourelatos, Tedeschi and Zaenen1981; Verkuyl, Reference Verkuyl1993, Reference Verkuyl2008), temporal frame of reference (the enunciator’s frame of reference vs. the speaker’s/external frame of reference vs. a narrative frame of reference), intervals and boundaries (open vs. closed situation boundaries) and semantic invariant (the aspectual and temporal semantic content, common to all contextual values that a verbal tense may have). As such, the IMP expresses a temporal differentiation (oriented towards the past) between an unaccomplished situation and the enunciator’s frame of reference while taking either a (stable) state value or an (evolutive) process value. The PS always expresses an event as disconnected from the enunciator’s frame of reference, and it is in contrast to the PC, which expresses either an accomplished event differentiated from the enunciator’s frame of reference or a (resultative) state successive to an accomplished event. In fact, according to Desclés’ model, the whole paradigm of the use of verb tenses in a text depends on the frames of reference. With the PS, for example, there is a change from the enunciator’s frame of reference towards the narrative frame of reference, knowing that the enunciator’s frame is detached from the speaker’s/external frame of reference.

In the second type of account, the distinction between the IMP and the PS comes from the fact that the former is an imperfective verbal tense while the latter is a perfective verbal tense.Footnote 5 According to this line of thought, imperfective verbal tenses which take an “internal perspective”, focusing on a sub-interval of an ongoing event, point to the speaker’s experiencing mind, and are therefore associated with subjective interpretations of utterances. Perfective verbal tenses, on the other hand, present the situation from an external perspective by offering a perception of the situation as a whole, and are thus associated with objective interpretations of utterances. According to Fleischman, the alternation PS/IMP has the pragmatic function to signal the change of perspective: “from an external perspective of the narrator to the inner speech and thoughts of the focalizing characters” (Fleischman, Reference Fleischman, Fleischman and Waugh1991: 35). Nevertheless, as Bres (Reference Bres2003) points out, this hypothesis of verbal tenses alternation is too general since in many cases the alternation PS/IMP does not involve a change of perspective, and changes of perspective may arise in the absence of the PS/IMP alternation. In fact, the predicted associations for perfective vs. imperfective verbal tenses and perspective have not found much support in the scant empirical studies to date (Trnavac, Reference Trnavac2006; Grisot, Reference Grisot2017). For Bres (Reference Bres2003), both the notion of grammatical aspect and of perspective have a role to play in how verbal tenses are used in the discourse. Precisely, grammatical aspect takes action at an early stage of the production of an utterance: it determines whether the eventuality is to be viewed as ongoing or as accomplished. The (subjective) perspective, which is optional, is built later and in interaction with the representation given by the verb itself, by grammatical aspect and tense, and by the context among others. As such, the notion of perspective is relevant with respect to the functioning of verbal tenses at the discursive level: it is a meaning effect or a contextual value drawing on grammatical aspect and on the context.

Pragmatic studies argued that most French verbal tenses have perspectival usages,Footnote 6 i.e. usages in which a subjective perspective is expressed, namely where there is a change in how they locate eventualities in time. Some of the best-known perspectival usages of French verbal tenses are the perspectival PS (1), futurate PC (5), future Présent (6), historical Présent (7) and narrative IMP (8).

-

(5) Demain j’ai fini mon article.

‘Tomorrow I will have finished my paper.’

-

(6) Je pars demain.

‘I am leaving tomorrow.’

-

(7) De 1917 à 1921 Jean Galmot vécut ses années les plus ardentes, les plus riches en péripéties, les plus dramatiques aussi. C’est l’ascension. On le laisse faire. Son succès surprend. (Moeschler, Reference Moeschler2019 from Jean Galmot)

‘Between 1917 and 1921 Jean Galmot lived his most intense years, the fullest of adventures, and the most dramatic. It is Holy Thursday. They let him do his job. His success was surprising.’ (our translation)

-

(8) Le lendemain, Paul partait. (Saussure, Reference de Saussure, Jaszczolt and de Saussure2013)

‘The next day, Paul left.’

In each of these four cases, there is a semantic tension between the temporal adverbial (a deictic expression) preceding the verb and the basic semantics of the verbal tense, a tension which is resolved semantically, textually or pragmatically depending on the scholars. According to scholars adopting the semantic answer, the solution would consist in a type of semantic accommodation of the semantics of verbal tenses in relation to the interval at which the situation is true (e.g. following Dowty’s Reference Dowty1979 proposal for futurate progressives, as in (6)). Scholars adopting a textual approach suggest that in opaque contexts (in the sense of Quine, 1960), in which there is an ambiguity relative to whose point of view is relevant in determining the truth-condition of a proposition (that of the speaker or of another person), temporal deictics signal a change of perspective: from that of the speaker to that of another person (called mediator, using Desclés and Guentchéva’s, Reference Desclés, Guentchéva, Monod-Becquelin and Erikson2000 term; cf. discussion in Apothéloz, Reference Apothéloz, Ferrari, Lala and Stojmenova2015). Finally, for scholars advocating the pragmatic answer, in these perspectival usages, there may be a shift of meaning of tenses under the pressure of linguistic and non-linguistic, contextual, information (as in Saussure, Reference de Saussure, Jaszczolt and de Saussure2013), or the meaning of verbal tenses is given by a core of semantic information (a basic configuration of the Reichenbachian coordinates moment of speech S, reference point R and event moment E; cf. Reichenbach, Reference Reichenbach1947) and a number of pragmatic features (as in Moeschler et al., Reference Moeschler, Grisot and Cartoni2012; Moeschler, Reference Moeschler2019). According to Saussure (Reference de Saussure, Jaszczolt and de Saussure2013), which builds on Sthioul (Reference Sthioul, Moeschler, Jayez, Luscher, de Saussure and Sthioul1998) and Saussure and Sthioul (Reference de Saussure and Sthioul1999; Reference de Saussure, Sthioul, Larivée and Labeau2005), the comprehender (referring to the reader or to the hearer) of the narrative IMP is prompted to change the reference point R (which is not perspectival in the regular usages of the IMP) for a perspectival point (Saussure, Reference de Saussure, Jaszczolt and de Saussure2013: 52).Footnote 7 With this perspectival reference point R, the comprehender interprets the eventuality expressed by the narrative IMP as ongoing from the point of view of a third party who perceives that action. For Saussure, this perspectival analysis is also supported by the fact that the narrative IMP cannot be replaced by a simple past when a marker of subjectivity (such as the adverbial déjà expressing the speaker’s surprise) accompanies the verb, as in (10) (as suggested by Sthioul, Reference Sthioul, Moeschler, Jayez, Luscher, de Saussure and Sthioul1998; cf. Saussure, Reference de Saussure, Jaszczolt and de Saussure2013: 52).

-

(9) Le lendemain, Paul partait déjà.

‘The next day, Paul has already left.’

-

(10) *Le lendemain, Paul partit déjà.

‘The next day, Paul already left.’

Another example of perspectival usage of French verbal tense is the futurate PC, which Saussure’s (Reference de Saussure, Jaszczolt and de Saussure2013) model explains in terms of the instantiation of a perspectival future moment of speech S’ (p. 56). S’ is a future projection of S, from which the eventuality E is represented as past, as illustrated in example (5). So, it cannot be established that a deterministic pattern of the type PS or PC uniquely triggers objective interpretations, nor that IMP uniquely triggers subjective interpretations.

Notwithstanding the technical details which each of these approaches proposes, there is agreement that these non-prototypal usages are perspectival, in the sense that they express the speaker’s perspective (and knowledge) of the eventuality expressed, and that this is key to resolving the tension between the temporal adverbial and verbal tense. In other words, the comprehender is invited to take the speaker’s perspective when reading this type of perspectival usage of verbal tenses in order to interpret them.

3. STUDY 1: ANNOTATION TASK WITH CORPUS DATA

3.1. Hypotheses and predictions

The previous studies presented in section 2 give rise to a series of hypotheses, and their subsequent predictions for empirical testing.

The observations principally made by studies in linguistic literary criticism draw on the hypothesis that perfective verbal tenses, such as the French PC and PS, do not involve the instantiation of a subjective experiencing self and express a situation in an objective manner, whereas imperfective verbal tenses, such as the French IMP, present a situation in a subjective manner as experienced by a self (the speaker or a third-party). This hypothesis would predict that annotation tasks show evidence that these associations are statistically significant. By contrast, the observations made by pragmatic studies draw on the hypothesis that verbal tenses have basic usages (in which they have a primarily referential function), and interpretative or perspectival usages, which arise in specific co(n)textual conditions. In this case, annotation tasks would show corpus excerpts annotated as subjective and objective for each of the three verbal tenses tested. To test both hypotheses, we carried out an annotation task in which a group of annotators read corpus excerpts containing occurrences of the PS, PC and IMP, and annotated them as subjective or objective.

To investigate whether the subjective interpretation of an utterance arose primarily due to its verbal tense, we carried out the annotation task on two versions of the corpus data: a second group of annotators read exactly the same corpus excerpts, but with the verbal tenses concealed, and annotators seeing the verb in its infinitive form. Our working hypothesis is as follows: if it is the verbal tense of a sentence which gives access to the speaker’s subjectivity, the results for the first version of the data will be different from those for the second version of the data, as verbal tenses were concealed in the latter.

3.2. Material, procedure and participants

We used Grisot’s (Reference Grisot2015) corpus data, which contains texts from three stylistic registers in equal proportions: literature, journalism and discussions from the European Parliament. In this study, we randomly selected and used 214 corpus excerpts containing 65 occurrences of the PS, 72 occurrences of the PC and 77 occurrences of the IMP.

For our annotation task, we manipulated annotators’ access to verbal tense: in the first annotation task, one group of annotators read corpus data where the verbs were inflected, as in (11); in the second annotation task, another group of annotators read corpus data where the verbs were not inflected (i.e. were in their infinitive form), as in (12).

-

(11) Le principe des quatre cinquièmes des États membres figurait déjà dans les propositions initiales qui avaient été déposées par la Commission Prodi. [EuroParl]

-

(12) Le principe des quatre cinquièmes des États membres figurer déjà dans les propositions initiales qui avaient été déposées par la Commission Prodi. [EuroParl]

‘The principle of four fifths of the Member States was already included in the initial proposals which had been tabled by the Prodi Commission.’

All annotators received annotation guidelines, underwent a training phase with discussion of the annotation guidelines, and then annotated the data independently. The annotation guidelines provided a definition of subjectivity and a typical example from a literary text provided in (13), in which the author narrated a series of events in a subjective way. Here, Flaubert narrates a series of events (Emma Bovary had to go downstairs; she had to sit at the table; she tried to eat; the pieces of food choked her) in a subjective way: he gives the reader access to Emma’s subjective point of view.

-

(13) – Monsieur vous attend, madame, la soupe est servie. Et il fallut descendre ! Il fallut se mettre à table ! Elle essaya de manger. Les morceaux l’étouffaient. (Flaubert, Madame Bovary)

‘Monsieur is waiting for you, madame, the soup is served. And she had to go down! She had to sit at the table! She tried to eat. The pieces were suffocating her.’ (our translation)

Subjectivity was broadly defined in the guidelines as referring to the fact that speakers may communicate, via language, their personal points of view, evaluation of a certain situation, emotions and psychological states. Speakers may also communicate the points of view, evaluation, emotions and psychological states of a third party; these types of utterances are subjective utterances. In contrast, an utterance is objective when the speaker describes a situation or narrates a series of events in an objective way, thus without expressing her subjective point of view, evaluation, emotions or psychological states.

There were 66 participants, all native speakers of French. At the time of the experiment, they were 1st year Bachelor’s students at the Faculty of Humanities at the University of xxx. Their participation in the experiment took place during a linguistics class. It was the first time they had participated in this type of experiment. After the annotation guidelines had been shown, each participant received on paper the corpus excerpts to be annotated. One group of participants received the version of corpus data in which the verbs were inflected; the other received the version of the corpus data in which verbal tenses were concealed. The corpus excerpts were distributed in 22 sets (11 sets for each version of the corpus data); each annotator read only one set, and each set was annotated by three independent annotators. The task was performed in approximately 15 minutes.

3.3. Results

For each version of the data, we calculated the mean inter-annotator agreement rates by calculating the agreement rates for each pair of annotators (A1-A2, A2-A3 and A1-A3). The mean inter-annotator agreement rate was 68% for the version of data where verbs were inflected and 64% for the version where verbal tenses were concealed. Since these inter-agreement rates are not much higher than chance (0.5 in a binary categorization), we carried out further analyses on the corpus excerpts which had full agreement among the three annotators: 112 for the first version of the data, and 97 for the second.

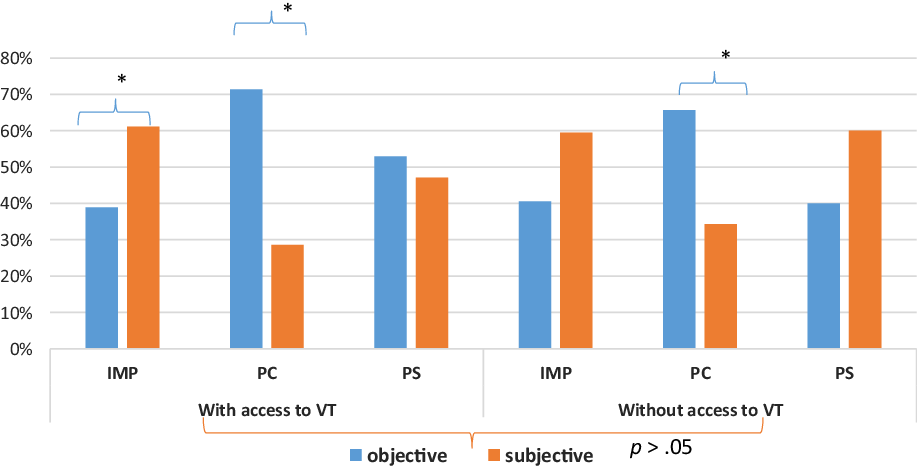

Figure 1 shows how annotators annotated the corpus excerpts containing an IMP, a PC and a PS as subjective or objective. The left-hand panel provides results for the first version of the data, where annotators had access to the verbal tense, while the right-hand panel shows how annotators annotated the corpus excerpts from the second version of the data, where initial occurrences of PC, PS and IMP were removed.

Figure 1. Results of the annotation task for the first vs. second version of the data.

The first series of results, from the first version of the data, is as follows: corpus excerpts where the IMP occurs were significantly more often annotated as subjective rather than objective; by contrast, those where the PC occurs were significantly more often annotated as objective rather than subjective. Finally, those where the PS occurs were annotated as subjective and objective with equal frequency (X2 (8.42), 2, p=0.0148).

The second series of results, from the second version of the data, is as follows: corpus excerpts with a concealed PC were significantly more often annotated as objective rather than subjective; those with a concealed IMP tended more often to be annotated as subjective than objective; finally, those with a concealed PS were annotated as subjective and objective with equal frequency (X2 (5.77), 2, p=0.0559).

The third result regards the comparison between the distribution observed in the first and second versions of the data: a chi-square test of independence showed that there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups of data points (X2 (0.5), 1, p=0.4795). In other words, corpus excerpts were annotated in the same way, whether or not annotators had access to the verbal tense.

3.4. Discussion

The results of Study 1 show that the three verbal tenses tested had subjective and objective uses. The IMP is used frequently in excerpts with subjective interpretations, whereas the PC is frequently used in those with objective interpretations. The PS occurs equally frequently in excerpts with subjective and objective interpretations. These results replicate those from Grisot (Reference Grisot2017) with respect to the PC and the IMP, but not the PS. In Grisot (Reference Grisot2017), we carried out the same task but only on the first version of the data (annotators had access to the verbal tenses), and with different annotators; we compared the results for French verbal tenses with those for the English Simple Past and the Serbian morphological marking of perfective vs. imperfective aspect. We concluded that French verbal tenses expressing past time do not seem to provide privileged access to speaker’s perspective; however, the IMP and PS are preferred when expressing the speaker’s subjective perspective, where the PC is preferred when describing a situation objectively.

The results from Grisot (Reference Grisot2017) and from the current annotation study only partially confirm the hypothesis defended by studies in linguistic literary criticism (section 3.1), according to which imperfective verbal tenses have subjective usages whereas perfective verbal tenses have objective usages. Indeed, we did not find supporting evidence regarding the PS. One possible explanation for the statistically significant association between the IMP and subjective interpretations is linked to its (grammatical) aspectual content. Precisely, while perfective tenses express most frequently events, imperfective tenses express in general states,Footnote 8 such as mental states (thoughts and opinions), and take action at the discursive level (Bres, Reference Bres2003). Thus, this type of subjective content is more likely to be expressed with the IMP than with the PS.Footnote 9 Another explanation of these results seems to come from the hypothesis defended by pragmatic studies, which predicts that the PC, PS and IMP have both subjective and objective usages. However, according to this approach, subjective usages correspond to perspectival usages which arise in very specific cotextual conditions, such as the semantic incompatibility between the temporal adverbial and the verbal tense, among others. If we look at examples annotated as subjective in both Grisot (Reference Grisot2017) and the current annotation task ((14) for the IMP, (15) for the PS and (16) for the PC), it is clear that they do not present the very specific cotextual conditions predicted by the pragmatic studies. In fact, in the 50 subjective excerpts from the set of data that received full agreement among the three annotators, we did not find any of the perspectival usages of verbal tenses discussed in section 2 (with semantic incompatibility between temporal adverbial and verbal tense).

-

(14) Or mon petit bonhomme ne me semblait ni égaré, ni mort de fatigue, ni mort de faim, ni mort de soif, ni mort de peur.

‘And yet my little man seemed neither to be straying uncertainly among the sands, nor to be fainting from fatigue or hunger or thirst or fear.’

-

(15) Sans résultat. Les catholiques, flairant le piège, se rallièrent autour de leur Souverain pontife, et quand on les contraignit à choisir entre leur foi et leur fidélité à l’Etat, penchèrent souvent en faveur de la première.

‘No result. Catholics scented another agenda, rallied round their Pontiff, and when forced to choose between faith and loyalty to the state, often chose the former.’

-

(16) C’est la raison pour laquelle nous avons vraiment préparé, en commission, cette deuxième lecture en un temps record, et nous l’avons présentée en session plénière afin d’avoir le temps de mener les négociations sur une base sérieuse avant la fin de cette année.

‘This means that only a conciliation procedure can resolve the problem, so, in the committee, we prepared the second reading and presented it to plenary in what really was record time, so that we would have enough time to conduct the negotiations, on a serious basis, before the year is over.’

Crucially, what the current annotation study adds to this picture is the fact that annotators annotated the two versions of the data (with and without access to verbal tense) in the same way. This means that annotators built the subjective interpretations of the corpus excerpts they read on the basis of linguistic cues other than verbal tenses. Grisot (Reference Grisot2019), which carried out a further corpus annotation task targeting the linguistic expression of the speaker’s subjectivity in French, found that evaluative lexicon (such as modal verbs and adverbs, and causal connectives in their epistemic usages), affective lexicon (such as adjectives, verbs, adverbs, nouns and expressives) and certain types of syntactic structure (such as cleft sentences) were the most frequent linguistic phenomena which speakers have at their disposal to express their subjectivity. On this basis, we believe it possible that annotators in Study 1’s annotation task built subjective interpretations of the corpus excerpts they read using the same types of linguistic cue as those found in Grisot (Reference Grisot2019), explaining the fact that they annotated the two versions of the data in a similar way.

In summary, the current study’s empirical results chime with those of Grisot (Reference Grisot2017, Reference Grisot2019), suggesting that verbal tenses do not themselves trigger the subjective interpretations of utterances, but that their subjective usages draw on subjective interpretations of utterances triggered by other types of linguistic cue, like the above-mentioned from Grisot (Reference Grisot2019). However, there is the outstanding issue of the perspectival usages of the verbal tenses tested, which arises in specific cotextual conditions: is perspective-taking responsible for the perspectival usages of verbal tenses? We investigated this issue in Study 2, which targeted the perspectival usage of the PS seen in Aujourd’hui, personne ne lui adressa la parole (‘Today, nobody talked to him’) (Vuillaume, Reference Vuillaume1990; section 1).

4. STUDY 2: SELF-PACED READING EXPERIMENT WITH THE PS

4.1. Hypotheses and predictions

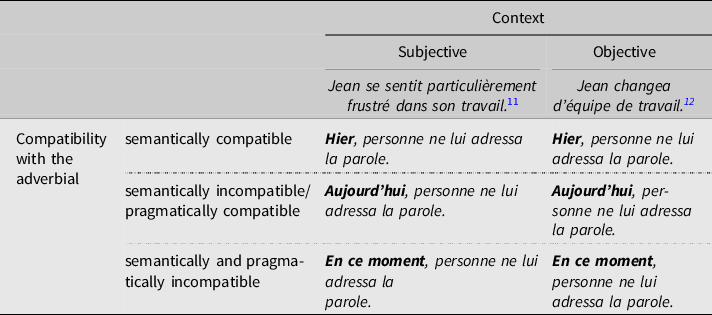

To investigate whether perspectival usages of verbal tenses lead to subjectivity, we carried out a self-paced reading experiment with a 2x3 within-group design, with two variables: the type of context, with two levels (subjective and objective); and the compatibility with the adverbial status, with three levels (semantically compatible with hier ‘yesterday’, semantically incompatible but pragmatically compatible with aujourd’hui ‘today’, and semantically and pragmatically incompatible with en ce moment ‘in this moment’), as in Table 1.Footnote 10 We explain the two variables and the predictions we make below.

Table 1. The 2x3 experimental design

The hypothesis is that if perspective usages are subjective, we would expect a facilitation effect regarding the processing of sentences like Aujourd’hui, personne ne lui adressa la parole when they are preceded by a subjective — rather than objective — context. We expect that perspective-taking, as one of the components of subjectivity, will be facilitated in a subjective context. Therefore, we predict longer reading times when the target sentences are read in an objective context than when they are read in a subjective context.

Furthermore, the perspectival usage of the PS is characterised by a semantic incompatibility between a present time adverbial (aujourd’hui ‘today’, which situates an eventuality E as simultaneous to the moment of speech S) and a past time verbal tense (which situates E as preceding and completely Footnote dissociated from SFootnote 13 ). According to the pragmatic studies discussed in section 2, this semantic incompatibility is resolved pragmatically by perspective-taking: the comprehender is invited to take the speaker’s perspective on the eventuality expressed by the verb. At the same time, there is no semantic incompatibility between a past time adverbial, such as hier ‘yesterday’, and the PS, where the PS has a regular, referential, usage. We expect an interaction effect between the type of context (subjective vs. objective) and the compatibility status with the adverbial variable, according to which — in objective contexts — sentences with semantic incompatibility between verbal tense and adverbial are harder to process than sentences with no such incompatibility (such as hier, personne ne lui adressa la parole), due to the lack of the facilitating effect of the subjective context. Finally, we established a control condition, in which the PS co-occurs with a different type of present time adverbial (en ce moment ‘in this moment’, which situates E as coinciding with S). This type of semantic clash is not resolvable either semantically nor pragmatically, as is the case with the adverbial aujourd’hui (which is the perspectival usage of the PS). We expect to find significantly longer processing times for en ce moment than for hier and aujourd’hui.

4.2. Participants

Participants in this experiment were 41 students from the University of XX, Faculty of Humanities (18 females, mean age: 22.75, range 18–32). All participants were native speakers of French. Their participation in the experiment was paid, and voluntary.

4.3. Material and procedure

Two of the experimental conditions shown in Table 1 are illustrated below: the subjective and semantically compatible condition in example (17); and the objective and semantically incompatible but pragmatically compatible condition in (18).

-

(17) Context sentence: [Jean fut embauché 1] [dans une grande banque privée. 2]

Biasing sentence: [Il se sentit 3] [particulièrement frustré. 4]

Target sentence: [Hier,5] [il se disputa avec un collègue 6] [du bureau. 7]

‘John was hired by a big private bank. He was feeling particularly frustrated. Yesterday, he quarreled with a colleague from the office.’

-

(18) Context sentence: [Jean fut embauché 1] [dans une grande banque privée. 2]

Biasing sentence: [Il changea d’équipe 3] [de travail. 4]

Target sentence: [Aujourd’hui,5] [il se disputa avec un collègue 6] [du bureau. 7]

‘John was hired by a big private bank. He changed. Yesterday, he quarreled with a colleague from the office. He changed the work crew.’

Each experimental item consisted of three sentences: the context, the biasing sentence and the target sentence. The context sentence was identical in all six conditions; its role was to set the context. The biasing sentence oriented comprehenders towards a subjective (17) or objective (18) interpretation of the short narrative. The subjective biasing sentences were created by using affective linguistic cues of subjectivity; the objective biasing sentences were created by avoiding any of the known linguistic cues of subjectivity related to the three components of subjectivity.

The three sentences were divided into several regions, as shown in examples (17) and (18).Footnote 14 Reading times were measured for all seven regions, but the three regions of interest were in the target sentence: region 4 (the adverbial), region 5 (the subject-verb-complement) and region 6 (the adjunct).

The material was pre-tested to check for the subjective and objective interpretations of the biasing sentence, and to keep constant the type of discourse relation in such a way that the target sentence was always an explanation of the biasing sentence. Controlling for discourse relation was important, since it is well known that different discourse relations are not processed with equal speed (Kuperberg et al., Reference Kuperberg, Paczynski and Ditman2011). All biasing sentences were confirmed to have a subjective or objective interpretation by three independent coders. In terms of the second issue, by inserting the connective parce que ‘because’ we checked that all target sentences were explanations for the preceding biasing sentences. Moreover, the coders equally accepted the sentences in which the PS co-occurs with the adverbial hier and with the adverbial aujourd’hui, and did not signal grammaticality issues.

The 30 experimental items had a variant in each experimental condition, resulting in 180 variants of the experimental items. Twenty-four fillers, having the same structure as the experimental items, were also used in the experiment. The resulting 180 versions of the experimental items were distributed in six lists, and within each list, in eight blocks. Each participant only saw one list consisting of 54 short narratives (30 items and 24 fillers) and read experimental items from all six conditions. The order of presentation was randomised. A total of 24 yes/no comprehension questions (three per block) appeared randomly within each list to assess the participants’ level of attention. Participants could answer by pressing a key for yes or for no, according to their choice. For example, the experimental item from (17) and (18) would be followed by this comprehension question, and would require a no answer:

-

(19) Jean, a-t-il été embauché dans un cinéma ?

‘Was John hired by the cinema?’

The experiment was designed with the E-prime software (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Eschman and Zuccolotto2012) as follows. Each session began with written instructions displayed on the screen, followed by a training phase, in which the participants saw two short narratives similar to the items and three short narratives similar to the fillers. At the end of the training phase, the participants were given the opportunity to ask questions of the experiment’s coordinator before the actual experiment started. Each series of regions began with a fixation cross in the middle of the screen for 1000ms. On pressing the space bar, the different regions appeared consecutively on the screen, and remained on the screen as the readers went on to the next region.Footnote 15 There was no time constraint imposed for the task, and each participant completed the experiment within approximately 15 minutes.

4.4. Analysis

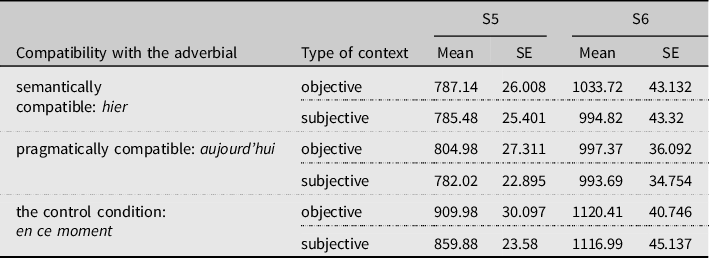

All answers to the comprehension questions were checked. Two participants had a success rate of less than 70% and were removed from the data set. For the remaining 39 participants, the general level of success in the comprehension questions was 86%. Before conducting the analysis, the data were cleaned in two phases. In the first phase, extreme values were removed by deleting observations under 50ms. and over 4000 ms. measured for all the segments starting with the biasing sentence, as these reading times are not considered in the literature to represent normal reading times for short segments like those used in our experiment (cf. Zufferey, Reference Zufferey2014). Then, outliers were removed from the data by removing all observations above and below three standard deviations from the subject’s mean values for each of the three main target regions (adverbial, subject-verb, and complement of the target sentence). This corresponded to a total of 86 observations (8% of the data). The mean reading times (standard errors SE between parentheses) for the two target regions (as illustrated above in examples (17) and (18) in each of the six experimental conditions) are reported in Table 2.

Table 2. Mean reading times and standard errors (ms.) for the target regions

Data were analysed by fitting linear mixed-effects models using the R software (R Development Core Team, Dalgaard, Reference Dalgaard2010, version 3.1.2). This lets both participants and items be included as random factors in all analyses, therefore avoiding the “language-as-fixed-effect-fallacy” by separating F1 and F2 analyses (Brysbaert, Reference Brysbaert2007; Clark, Reference Clark1973). Models were tested using the lmer() function of the lmer4 package of R, and model comparisons were assessed using the anova() function, which calculates the chi-square value of the log-likelihood to evaluate the difference between models, following Baayen’s (Reference Baayen2008) procedure.

Following Field et al. (Reference Field, Miles and Field2014), we built the models by going from the simplest model to the one of interest. In the first analysis, for each of the two target regions, we first tested a model that only encompassed items and participants as random factors (i.e. random intercepts). We then compared this model to one including the compatibility with the adverbial status as a fixed factor, and finally one that incorporated both compatibility status and type of context (and their interaction) as fixed factors.

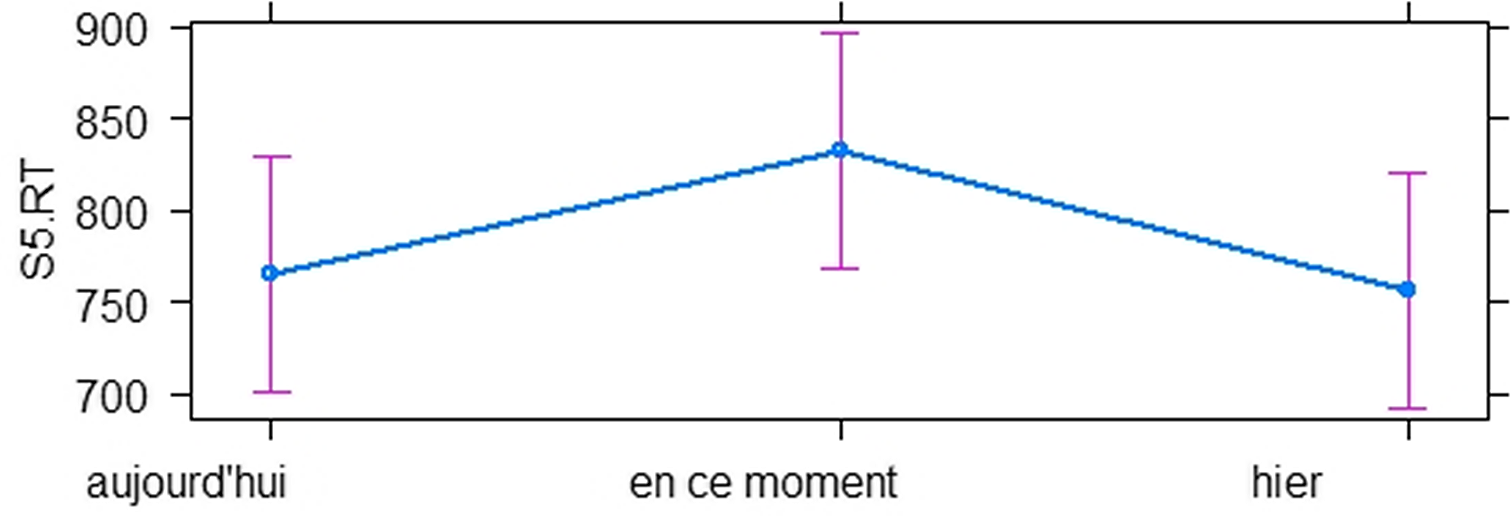

4.5. Results

In the adverbial region of the target sentence (region 5), adding the compatibility with the adverbial variable to the simplest model (which only included items and participants as random effects) significantly improved the model (Δχ2 = 23.41, Δdf = 2, p < .001). As expected, reading times in the control condition with en ce moment (the semantically and pragmatically incompatible condition) were significantly longer (M = 884.58, SE = 19.07) than those recorded with hier (the semantically compatible condition; M = 786.30, SE = 18.11), as well as those recorded in the target condition with aujourd’hui (the semantically incompatible but pragmatically compatible condition; M = 794, SE = 17.95). This result, shown in Figure 2, confirms that our experiment functioned correctly. Furthermore, the processing times in the hier and aujourd’hui conditions were similar (M = 786.30, SE = 18.11 and M = 794, SE = 17.95 respectively), indicating that the semantic incompatibility from the target condition (aujourd’hui) was pragmatically resolved.

Figure 2. Mean reading times for S5 (the adverbial region).

However, adding the type of context did not further improve the model’s fit (Δχ2 = 1.58, Δdf = 1, p > .05, ns.), as the processing time of the adverbial region did not vary with respect to the type of context. In section 4.1, we formulated the prediction that a subjective context will facilitate access to the perspective-taking component. As such, we expected longer reading times when the target sentence was read in an objective context than in a subjective context. This prediction is not confirmed by our results, as the reading times measured for the adverbial aujourd’hui in the objective context (M = 804.98, SE = 27.31) were similar to those measured in the subjective context (M = 785.48, SE = 25.40). In addition, we predicted an interaction effect according to which — in objective contexts — sentences presenting the perspectival usage of the PS with aujourd’hui would be harder to process than sentences presenting a regular usage of the PS with hier, because the facilitating effect of the subjective context is lacking. Again, our results did not confirm this prediction, as we found similar reading times for the adverbial region in the objective context when the adverbial was aujourd’hui (M = 804.98, SE = 27.31) as we did when it was hier (M = 787.14, SE = 26.00).

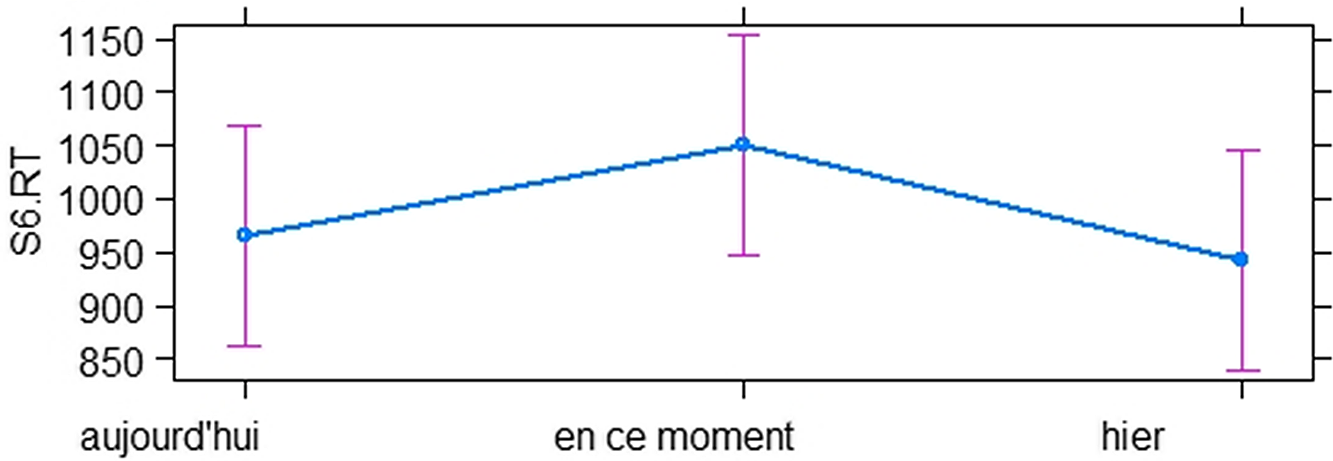

In the subject-verb region of the target sentence (region 6), we found similar results to those found in the previous region. Adding the compatibility with the adverbial variable to the simplest model (which only included items and participants as random effects) significantly improved the model (Δχ2 = 20.94, Δdf = 2, p < .001). As expected, reading times in the control condition with en ce moment (the semantically and pragmatically incompatible condition) were significantly longer (M = 1118.68, SE = 30.40) than those recorded with hier (the semantically compatible condition; M = 1014.05, SE = 30.54), as well as those recorded in the target condition with aujourd’hui (the semantically incompatible but pragmatically compatible condition; M = 995.61, SE = 25.08). This result is shown in Figure 3. As with the previous region, the processing times in the hier (M = 1014.05, SE = 30.54) and aujourd’hui conditions are similar (M = 995.61, SE = 25.08), suggesting that the semantic incompatibility from the target condition (aujourd’hui) was pragmatically resolved.

Figure 3. Mean reading times for S6 (the subject-verb-complement region).

However, adding the type of context did not further improve the model’s fit (Δχ2 = 0.01, Δdf = 1, p > .05, ns.), as the processing time of the subject-verb-complement region did not vary with respect to the type of context. As with the previous region, our results show that the reading times measured on the subject-verb-complement, when it was preceded by the aujourd’hui adverbial, were similar in the objective context (M = 997.37, SE = 36.09) and the subjective context (M = 993.69, SE = 34.75). As for the interaction effect that we predicted, the results show that — in the objective context — reading times when the subject-verb-complement region was preceded by adverbial aujourd’hui (M = 997.37, SE = 36.09) were similar to those when it was preceded by the adverbial hier (M = 1033.72, SE = 43.13).

4.6. Discussion

The results of our experiment raise two issues. The first issue regards the behaviour of the PS, which locates by its semantics the E as simultaneous with R, which precedes and is completely dissociated from S, when it co-occurs with one of the three adverbials tested. A few words should be said about these temporal adverbials. They are deictic linguistic units, called shifters in Jespersen’s and Jakobson’s terminology (in French embrayeurs) whose meaning obligatorily involves reference to the uttering situation to find the referred moment (Kleiber, Reference Kleiber1986; Jollin-Bertocchi, Reference Jollin-Bertocchi2003). Like the adverb maintenant (‘now’) (Klum, Reference Klum1961), the adverb en ce moment expresses contemporaneity of its referred moment and the moment of speech, as well as the negation of an anterior interval (Vuillaume, Reference Vuillaume1990; Jollin-Bertocchi, Reference Jollin-Bertocchi2003). Both adverbials express a punctual present time moment and frequently co-occur with the Présent or the lexical paraphrase être en train de (‘be +ing’). The adverb aujourd’hui also expresses contemporaneity of its referred time, which is not punctual (as with en ce moment) but indicates an interval of time, with S. Finally, the adverb hier expresses that its referred time is an interval of time which precedes S.

So, the PS is completely incompatible with the adverbial en ce moment, which expresses a strong coincidence between the referred moment and S, and at the same time negates any interval of time anterior to S. As such, the semantics of this adverbial is both semantically and pragmatically incompatible with the semantics of the PS, which locates an event as dissociated and previous to S. The semantic incompatibility of the PS with the adverbial aujourd’hui is questionable: it holds with respect to the fact that aujourd’hui expresses a referred time that is contemporaneous with S, but does not hold with respect to the fact that aujourd’hui expresses an interval of time which consists of at least three sub-intervals of time (the first is previous to S, the second is contemporaneous to S, and the third is subsequent to S). As such, it is plausible that participants understood the sentence aujourd’hui, personne ne lui adressa la parole as locating the situation in the first sub-interval of time denoted by the adverbial aujourd’hui. In this case, one cannot speak of a semantic incompatibility which is resolved pragmatically by perspective-taking, but of a semantic compatibility by narrowing the semantics of the adverbial to one of its sub-intervals (that which precedes S). It may be that perspective-taking is restricted to this narrowing move. Finally, the PS is semantically compatible with the adverbial hier, and the participants’ processing times confirm that they did not encounter any difficulties when they read the PS co-occurring with this adverbial.

The second issue regards perspective-taking as a component of speaker’s subjectivity. In this experiment, we expected the objective vs. subjective manipulation of the context to have an effect on the processing of the perspectival usage of the PS co-occurring with a present time adverbial. We built this prediction according to the assumption that perspective-taking is a component of speaker’s subjectivity, and that this perspectival usage of the PS is a subjective usage (studies cited in section 2). The results of our experiment do not support this hypothesis, as we found similar reading times measured for the region of the adverbial aujourd’hui in the objective and subjective contexts. The same result was found for the subject-verb-complement region of the target sentence. Similarly, we did not find the predicted processing difficulties of the adverbial region, nor of the subject-verb-complement region, of the target sentence in the semantically incompatible but pragmatically compatible (i.e. aujourd’hui) condition compared to the semantically compatible (i.e. hier) condition in the objective context. We believe that there may be two explanations for this finding related to the status of perspective-taking as a potential component of speaker’s subjectivity. We develop this issue in section 5.

5. GENERAL DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The research question we explored in this article is whether French verbal tenses give access to speaker’s subjectivity via perspective-taking. To answer this question, we carried out two studies: an annotation study, and a self-paced reading experiment.

In the annotation study, our aim was to examine predictions made by two groups of studies (the first in linguistic literary criticism and the second from a pragmatic approach) regarding the possibility of a deterministic relation between perfective vs. imperfective verbal tenses and objective vs. subjective interpretations of utterances. For the linguistic literary criticism approach, this relation is deterministic, in the sense that perfective verbal tenses give rise to objective interpretations where imperfective verbal tenses give rise to subjective interpretations. For the pragmatic approach, this relation is not deterministic, since verbal tenses have both prototypical and non-prototypical usages, the latter being the subjective ones. The results of the annotation task do not favour this kind of deterministic relation, as we found that the three verbal tenses tested (PC, PS and IMP) have both subjective and objective usages. At the same time, we did find that sentences in which the IMP occurs are significantly more frequently understood as subjective, whereas sentences in which the PC occurs are significantly more frequently understood as objective. The same study also showed that annotators interpreted the corpus excerpts when they had access to verbal tense (the first group of annotators) in the same way as they did when verbal tenses were concealed (the second group of annotators). This finding is important, as it indicates that the subjective interpretations of the corpus excerpts in which the PC, PS or the IMP occur are not triggered by the verbal tense itself, or at least not only by the verbal tense, but principally by other cues. Building on the results from Grisot (Reference Grisot2019), we suppose that the subjective interpretations most probably drew from linguistic cues such as the affective and evaluative lexicon, and non-canonical syntactic structures (like cleft sentences and other types of fronted phrases) which were found to be the most frequent categories of linguistic cue of the speaker’s subjectivity. For example, the literary corpus excerpt from (20) (from Grisot, Reference Grisot2019: 31) was annotated by three independent annotators as expressing the speaker’s subjectivity. According to these annotators, this interpretation draws on the following linguistic cues: the affective-evaluative lexicon profiteur ‘profiteers’, spéculateurs ‘speculators’, nouveaux riches ‘the nouveau riche’ and des douzaines ‘dozens’, as well as the fronted syntactic structures comme tous les profiteurs [.] ‘like all profiteers’, on en attribuait […] ‘people thought’.

-

(20) Comme tous les profiteurs, les spéculateurs, les nouveaux riches de France achetaient des châteaux, on en attribuait des douzaines à Galmot. (B. Cendrars, Rhum) [BC025]

‘Like all profiteers and speculators, the nouveau riche of France bought castles, and people thought Galmot had dozens.’ (our translation)

Another example is the journalistic corpus excerpt from (21) (from Grisot, Reference Grisot2019: 33), also annotated by three annotators as subjective, an interpretation which they attribute to the following linguistic cues: the cleft sentence c’est […] que […] ‘it is […] that […]’, the pronouns leurs ‘their’ and nos ‘our’, the lexicon journal de reference ‘benchmark newspaper’, and the future time verbal tense continuera ‘will continue’.

-

(21) C’est grâce à leurs talents, leur expertise et l’acuité de leur regard que Le Monde continuera à répondre à votre légitime exigence et restera le journal de référence que vous lisez sur tous nos supports, papier et digitaux. (Le Monde, year 2012) [LM031]

‘It is thanks to their talents, their expertise and their keen eye that Le Monde will continue to meet your legitimate requirements and will remain the benchmark newspaper that you read on all our media, paper and digital.’ (our translation)

In the self-paced reading experiment, we tested a very specific type of perspectival usage of verbal tenses: the usage where the PS co-occurs with the present time adverbial aujourd’hui, as in aujourd’hui, personne ne lui adressa la parole. We manipulated the context (as objective or as subjective) and the adverbial (hier, aujourd’hui and en ce moment) to test whether the processing of this perspectival usage of the PS is facilitated by subjective contexts built with affective linguistic cues. Our results did not support the thesis that this perspectival usage of the PS is subjective, in the sense of giving access to the speaker’s subjectivity.Footnote 16 We identify two possible explanations of this result.

The first possible explanation which would allow us still to consider perspective-taking as a component of speaker’s subjectivity is the following. Perspective-taking involves two phases: a first phase, in which the comprehender is invited to take the temporal perspective of the speaker (in example (1), it is Julien’s aujourd’hui); and a second phase, in which the comprehender is able further to infer information about the speaker’s thoughts, emotions and psychological states once he has taken in the speaker’s temporal perspective. This explanation draws on the incremental and expectation-based models of language processing (Altmann, Reference Altmann1988; Crain and Steedman, Reference Crain, Steedman, Dowty, Karttunen and Zwicky1985; Kehler and Rohde, Reference Kehler and Rohde2017), according to which, at each step of processing a discourse, comprehenders anticipate the next part by leaning on linguistic cues. In the case of perspective-taking, when coming across the adverbial aujourd’hui, the comprehender anticipates the possibility of taking the speaker’s perspective: he can infer information about the speaker’s thoughts, emotions and psychological states. This account is compatible with the theories of perspective shift suggested in the case of FID (Banfield, Reference Banfield1982; Schlenker, Reference Schlenker2004; Reboul et al., Reference Reboul, Delfitto and Fiorin2016). One of the most striking particularities of FID is that indexicals do not belong to the same context: tenses and pronouns depend on the context of speech (or the context of utterance, in Schlenker’s Reference Schlenker2004 terms), where other deictics (temporal adverbials and demonstratives) belong to the context of thought, in which the speaker’s or narrator’s thoughts are expressed (Schlenker, Reference Schlenker2004). In FID, there is a frequent shift between the context of utterance, which is the actual context of the story, and the context of thought. In cases like Aujourd’hui, personne ne lui adressa la parole, the adverbial aujourd’hui belongs to the context of thought, whereas the PS belongs to the context of utterance. So, this type of utterance is not contradictory, as the comprehender shifts between the two types of context. It is possible that participants in our experiment performed the first phase of perspective-taking but did not go on to the second phase, where they would have been able to infer the character’s thoughts, emotions and psychological state. In other words, they did not shift between the two contexts. It might be the case that the second phase (i.e. the shift from the context of utterance to the context of thought) is easier and more naturally accepted in the case of longer narrative stories or novels. Nevertheless, our current design does not allow us to distinguish between the two phases, so a further experiment is necessary to determine whether this is the case.

The second possible explanation is that perspective-taking is not a component of subjectivity. Recall how our results indicate that the PS might not be semantically incompatible with the adverbial if it is understood to refer to a generic or atemporal period of time (which encompasses sub-periods of time previous, simultaneous and posterior to S) rather than a restricted period of time which is uniquely simultaneous to S. Another point is linked to the presumed semantic incompatibility between the PS and aujourd’hui, predicted to be resolved pragmatically by perspective-taking. Our results seem to indicate that perspective-taking might not be a component of speaker’s subjectivity, but a different type of phenomenon. This proposal is supported by the previous theoretical distinction made by Kerbrat-Orecchioni (Reference Kerbrat-Orecchioni2004) between deictic subjectivity (expressed through a broad class of deictic elements, such as personal pronouns, demonstratives, verbal tenses, grammatical aspect and temporal adverbs, among others) and affective-evaluative subjectivity (referring to “the individual usages of the common [language] code”, and mainly expressed through the evaluative and affective lexicon) (p. 80). For Kerbrat-Orecchioni (Reference Kerbrat-Orecchioni2004: 165), deictic elements are not subjective, as they may not receive different assessments from one person to the next. By contrast, the use of affective and evaluative words and expressions may be questioned because they depend on the individual judgment made by each person. According to this proposal, perspective-taking (deployed for deictic subjectivity) would therefore not belong to speaker’s subjectivity, which might be restricted to its affective and evaluative components (cf. proposal made in Grisot, Reference Grisot2019, as well as in Blochowiak et al. Reference Blochowiak, Grisot and Degand2020, with respect to French causal connectives). As such, the perspectival usage of verbal tenses — including the PS co-occurring with aujourd’hui investigated here — should not be considered as authentic subjective usages (i.e. giving access to speaker’s subjectivity). In order to test this novel idea, that speaker subjectivity consists of two components (speaker emotions and speaker epistemic evaluation of propositions), we need to conduct further experimental research.