Introduction

Survivorship is emerging as an area of increased interest within the cancer sciences, with technological advances continuing to improve cancer survival rates. The importance of supporting patients’ post-treatment is recognised in national agendas with the NHS Achieving World-Class Cancer Outcomes: A Strategy for England 2015–2020 recognising living with and beyond cancer as one of their six key points to address to improve care for all patients diagnosed with cancer. 1 Prostate cancer (PC) is the fourth most prevalent cancer worldwide with 5-year cancer survival at 99% in 2009–2015, and therefore this cohort of patients contributes to a large population of cancer survivors. 2

Prostate cancer treatment options are dependent on the stage of the cancer, with the most common forms of treatment including radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy. Prostate cancer treatment often involves a combination of treatment modalities to control the disease and patients can develop a range of side effects. For example, radiotherapy is commonly associated with poorer bowel and urinary incontinence, whereas radical prostatectomy is commonly associated with sexual dysfunction. 3 This was proven from the research outcomes of the ProtecT trial, which compared side effect outcomes of different treatments for localised PC. 3

As survival rates have increased for PC, this has left survivors facing potential impact upon their psychological wellbeing. Traditionally, a biomedical model of care is used in the healthcare setting, rather than a holistic approach to care. The holistic approach supposes that mind and body are intertwined and should be treated as a whole, which is not the traditional medical view. There is increasing evidence demonstrating that health and illness are much more complex, which is illustrated by the biopsychosocial model. Reference Tripp, Verreault, Tong, Izard, Black and Siemens4 This has led to wider acknowledgement that patients whose psychological needs are met cope better with their illness.

Psychological symptoms can range from depression, adjustment disorder and anxiety. Reference Bruce5 In the most severe of cases, patients may suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Reference Bruce5 Other forms of psychological stress can present in the form of guilt, loss of control, anger, confusion, increased vulnerability and fear. Reference Chambers, Ng and Baade6 Side effects associated with PC treatment can also affect daily living such as continence issues and sexual dysfunction which can lead to relationship problems. Reference Thomas, Wooten and Robinson7

It is important to address the topic of understanding the psychological impact upon PC survivors to analyse how patient’s wellbeing may be affected post-treatment. The long-term physical side effects of prostate cancer treatments is currently understood; however the underlying impact this has on a patients quality of life (QoL) from a psychological perspective is not as widely understood.

The aim of this critical review is therefore to determine what impact PC treatments have upon the psychological wellbeing of patients with PC.

Method

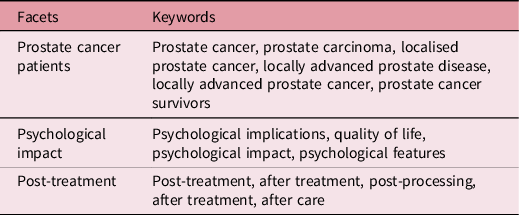

A search of electronic databases for the review including Science Direct, PubMed and PsychINFO was undertaken using the key search terms listed in Table 1.

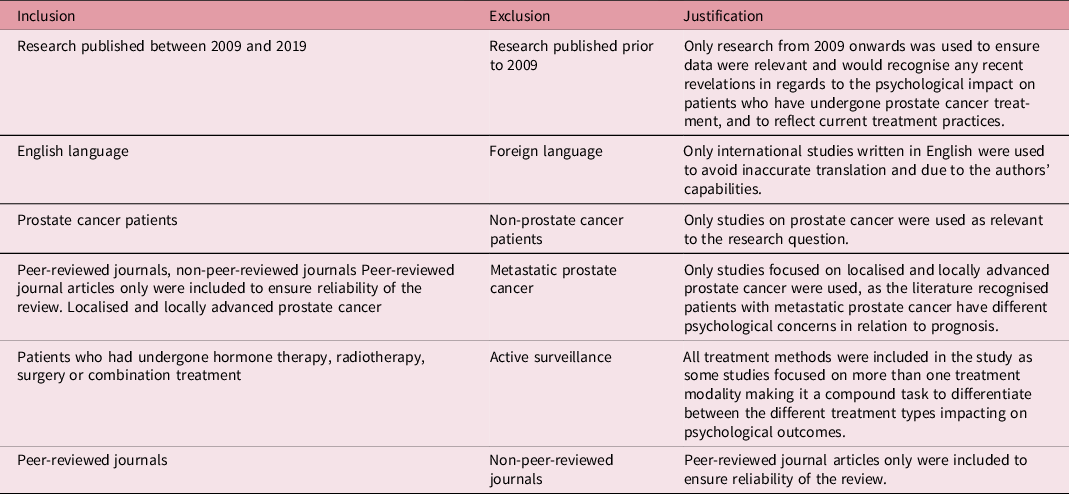

Table 1. A table representation of the critical review’s inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the articles found, to focus and determine the final articles for review.

Search strategy

Snowballing was used when papers were found through reference lists on other articles to ensure other applicable studies were not missed. This search was conducted from October 2018 to April 2019. The building-blocks technique was used to divide the query into facets to break up the research question into concept blocks (Table 2). The author scrutinised the titles, date and abstracts to identify eligible studies. The PRISMA flowchart was used to demonstrate the search process to improve the reporting of the critical review (Figure 1).

Table 2. A table showing the main facets behind the research question with relevant keywords that were used to conduct the literature search to ensure no relevant papers were lost

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart demonstrating the data selection process.

Articles that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were appraised using the appropriate Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklists relevant to the study design.

Results

In total 18 papers were identified as being eligible for the critical review, however, only 12 were selected that conveyed the common 3 themes identified; the 6 that were excluded focused on other psychological impact areas including fear of recurrence, PTSD and thoughts of suicide, which were mentioned less in the literature and thus this was not deemed a key theme to include in this review. A summary table can be found in the appendix for the included studies. The three key themes identified are discussed below:

Discussion

Masculinity

Masculinity can be defined as referring to the behaviours, social roles and relations of men within a given society as well as the meanings attributed to them. Reference Kimmel and Bridges8 Tsang et al. (2018) study demonstrated the words patients with PC most associated with masculinity were biologically based and included: sexual ability, sex drive and/or libido, being physically strong and maintaining bodily functions. Reference Tsang, Skead, Wassersug and Palmer-Hague9 This is alike to Chambers et al. (2017), Thomas et al. (2013) and Zaider et al. (2012) findings of association with the physical side effects of PC treatment, impacting on men’s perceptions of their masculinity. Reference Chambers, Ng and Baade6,Reference Thomas, Wooten and Robinson7,Reference Zaider, Manne, Nelson, Mulhall and Kissane10 . Both Chambers et al. (2017) and Zaider et al. (2012) recognised the impact of sexual dysfunction such as erectile dysfunction and loss of libido having the potential to impact on patients with PC having a lower perception of their masculinity. Reference Chambers, Ng and Baade6,Reference Zaider, Manne, Nelson, Mulhall and Kissane10 Men who perceive this lower masculinity in themselves could be at increased risk of experiencing distress due to changes in sexual functioning as a result of curative treatment. It is evident from the literature the importance men place on their ability to perform sexually to maintain their sense of masculinity, to the extent of influencing treatment choice because of the likelihood of erectile dysfunction post-treatment. Chambers et al. (2017) and O’Shaunessy et al. (2015) both recognised how some men chose radiotherapy over radical prostatectomy to preserve their sexual functioning, with men who did undergo radical prostatectomy having a deeper fear of sexual dysfunction post-treatment and thus impacting on patients psychologically. Reference O’Shaughnessy, Laws and Esterman11 Although much of the literature included in this study acknowledges the impact of sexual changes on men’s perceptions of their masculinity, this may be due to the resulting impact this can have on the individual’s personal relationships. Both Zaider et al. (2012) and O’Shaunessy et al. (2015) recognised the impact on adjustment in survivorship may rely on the quality of intimate relationships. Reference Zaider, Manne, Nelson, Mulhall and Kissane10,Reference O’Shaughnessy, Laws and Esterman11 Zaider et al. (2012) found the association between diminished masculinity and sexual bother was strongest for men whose spouses perceived low marital affection. Reference Zaider, Manne, Nelson, Mulhall and Kissane10 O’Shaunessy et al. (2015) addressed how men are conscious of how they are perceived by those they care about, and that men did not just view sex for pleasure, but as an expression of love for their partners. Reference O’Shaughnessy, Laws and Esterman11 Some men revealed in the interviews they felt a new appreciation of their relationships they may have previously taken for granted. Reference O’Shaughnessy, Laws and Esterman11 It could therefore be beneficial to reduce the threat to masculinity for clinicians to not just focus on improving the physicality of erectile dysfunction, but a focus around broadening perceptions of sexual relationships could help patients. Erectile dysfunction interventions should therefore incorporate masculinity in a holistic way due to masculinity perceptions framing how patients with PC interpret what is happening to them post-treatment, as suggested by Chambers et al. (2017). Reference Chambers, Ng and Baade6

Depression and anxiety

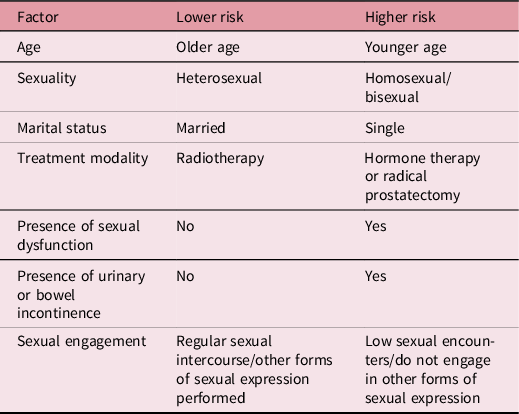

It is widely accepted across the literature that patients who have undergone treatment as a result of a cancer diagnosis are at greater risk of anxiety and depression, with Van Stam et al. (2017) comparing a general population sample of men of similar age with a population of PC survivors. Reference Van Stam, Van Der Poel and Rudd Bosch12 Fourteen per cent of males had mental health symptoms including anxiety, depression and distress in the PC survivor group, compared with 6% of the general population group. It is evident from the literature that there are a variety of risk factors that make patients who have undergone radical treatment to the prostate more at risk of developing psychological symptoms post-treatment. Albaugh et al. (2017) and Sharp et al. (2016), both identified anxiety and depression being reported in patients with sexual dysfunction and decreased sexual activity. Reference Albaugh, Sufrin, Lapin, Petkewicz and Tenfelde13,Reference Sharp, O’Leary, Kinnear, Gavin and Drummond14 Van Dam, Wassersug and Hamilton (2015) identified that different treatment modalities can impact on patients differently, causing differences in severity of anxiety and depression. Reference Van Dam, Wassersug and Hamilton15 Although all patients reported of mood worsening post-treatment in all modalities studied, those who had received Androgen deprivation therapy (ADTs) reported of greater negative mood changes. Reference Van Dam, Wassersug and Hamilton15 This could be due to the side effects attributed to ADT, such as hot flushes, gynaecomastia and weight gain, and this interlinks with the theme of masculinity, and how if this is impacted on, this can then lead to mental health changes in patients. Reference Van Dam, Wassersug and Hamilton15 Van Stam et al. (2017) and Sharp et al. (2016) also recognised the impact treatment side effects could have on patient’s mental health, and identified urinary dysfunction post-treatment as a risk factor for patients to go on to develop anxiety and depression. Reference Van Stam, Van Der Poel and Rudd Bosch12,Reference Sharp, O’Leary, Kinnear, Gavin and Drummond14 Age was additionally identified as a potential risk factor of anxiety and depression post-treatment, with younger patients at a heightened risk. Reference Letts, Tamlyn and Byers17 Other risk factors were being widowed, lower educational levels, lower general health perceptions, bodily pain, fatigue, insomnia and financial issues. Reference Van Stam, Van Der Poel and Rudd Bosch12,Reference Sharp, O’Leary, Kinnear, Gavin and Drummond14 These potential risk factors could be used in a predictive table, for side effects and sociodemographic information to be aware of that may put an individual more at risk of suffering psychologically post-treatment (Table 3). Watts et al. (2014) observed that prevalence of anxiety and depression is evident before treatment, reducing during treatment, before rising again post-treatment, which could be attributed to reducing during treatment as patients feel supported by healthcare professionals who they are seeing during their treatment. Reference Watts, Leydon and Birch16 Van Stam et al. (2017) and Watts et al. (2014) both recognise if attention is paid to modifiable factors that have been associated with increased risk of anxiety and depression, these mental health problems may be identified earlier and relevant support and treatment can be given. Reference Van Stam, Van Der Poel and Rudd Bosch12,Reference Watts, Leydon and Birch16 This could be in the form of an epidemiological investigation to screen for at risk of patients. Furthermore, treating and managing psychological distress should be a key clinical objective to enhance clinical outcomes and patient QoL. Van Dam, Wassersug and Hamilton (2015) advise for patients and partners to be made aware of the psychological implications before commencing treatments, for patients to be more aware of psychological side effects so appropriate help can be sought at its earliest opportunity. Reference Van Dam, Wassersug and Hamilton15

Table 3. A table of potential risk factors of depression and anxiety based on the critical review findings. This is a general guide. More research is required to prove this statistically but the table could be used as a guide to help healthcare professionals identify potential at-risk individuals

Psychological impact with sexual functioning

The impact of PC treatments can have on a patient’s sexual functioning is well understood from a biological basis; however, it is still an area not commonly discussed with patients before, during or after treatments. Reference Thomas, Wooten and Robinson7 Analysing the literature revealed common themes to arise from patients with PC post-treatment regarding their experiences post-treatment in relation to sexual dysfunction. The importance of support was highlighted by Thomas et al. (2013) and Albaugh et al. (2017) with a strong focus on individual support with tailored advice being imperative to improve patient experience post-treatment from a psychological perspective. Reference Thomas, Wooten and Robinson7,Reference Albaugh, Sufrin, Lapin, Petkewicz and Tenfelde13 This support was suggested to be utilised through support groups, spousal support groups and understanding from healthcare professionals to help with the healing process; it is evident from the literature that men may not actively seek support such as communicating with their partners or seeking assistance for restoring sexual function unless it was via more private means such as obtaining Viagra prescriptions. Reference Letts, Tamlyn and Byers17 The importance of partners was another theme to emerge in relation to the psychological impact of sexual functioning. Reference Thomas, Wooten and Robinson7,Reference Albaugh, Sufrin, Lapin, Petkewicz and Tenfelde13,Reference Letts, Tamlyn and Byers17 The importance of maintaining intimacy did help some patients post-treatment in regard to their sexual relationships. Letts, Tamlyn and Byers (2010) conducted a comparison study comparing questionnaire results pre-PC treatment, which identified men were engaging regularly in sex and were satisfied in their relationships, with post-treatment interviews. Reference Letts, Tamlyn and Byers17 The interviews revealed most men reporting no change in sexual desire; however, they were negatively affected in the form of distress due to erection changes, orgasm consistency and sexual satisfaction. Most men felt their sex lives were over and some stopped engaging in sexual activities; it is therefore evident how this could negatively impact on relationships and thus patient’s psychological wellbeing by removing an intimate constituent of patient’s personal relationships. Despite this, men reported of no change in the amount of affection expressed in their relationships in this study, Reference Letts, Tamlyn and Byers17 ; however, Thomas et al. (2013) identified in their study focusing on gay and bisexual men with PC, how the majority of participants had no spousal support. Reference Thomas, Wooten and Robinson7 Without this form of support, it could be suggested men of gay or bisexual orientation may be more at risk of suffering psychologically post-treatment. Treating patients as individuals in response to their sexual dysfunction was highlighted across much of the literature analysed including Hoyt & Carpenter (2015). Reference Chambers, Ng and Baade6,Reference Letts, Tamlyn and Byers17,Reference Hoyt and Carpenter18 This is due to the individual being affected differently in each case in response to changes in their sexual functioning, as well as different severities of sexual dysfunction presenting post-treatment. For example, the level of distress varied depending on the value men placed on sex or their perceptions of masculinity. Reference Hoyt and Carpenter18 Sexual-Self Schema (SSS) was identified as a factor of how much sexual dysfunction affected people depending on their own SSS, with a higher SSS and poor sexual functioning leading to more depressive symptoms being observed in these patients. Reference Hoyt and Carpenter18 Sexual-Self Schema therefore may be an important difference in determining the impact of sexual morbidity on psychological adjustment. Reference Hoyt and Carpenter18 Thomas et al. (2013) highlighted the need for individual support for gay and bisexual men to tailor support for their needs, as gay sexual practice often has to alter in response to PC patients receiving treatment and these patients therefore need individual care plans. Reference Thomas, Wooten and Robinson7 A need for accurate information regarding side effects in relation to sexual functioning is clearly an area requiring development as highlighted in the literature. Reference Thomas, Wooten and Robinson7,Reference Albaugh, Sufrin, Lapin, Petkewicz and Tenfelde13,Reference Letts, Tamlyn and Byers17 Letts, Tamlyn and Byers (2010) reported unsatisfactory communication regarding sexual side effects from physicians, and Thomas et al (2013) thematic analysis identified a need for information around this subject, with preparation for treatment side effects being inadequate. Reference Letts, Tamlyn and Byers17,Reference Thomas, Wooten and Robinson7 Understanding the impact of anticipated side effects in relation to sexual functioning is imperative to treatment satisfaction. Reference Albaugh, Sufrin, Lapin, Petkewicz and Tenfelde13 Alongside patient information giving, the sensitivity of healthcare professionals is key, in addition to when clinicians are helping patients with erectile dysfunction to broaden patient perceptions of sexual relationships as a way to help patients feel more supported. Reference Albaugh, Sufrin, Lapin, Petkewicz and Tenfelde13,Reference Letts, Tamlyn and Byers17

Conclusion

The results from this critical review illustrate the complexity of the psychological impact that treatments can have on PC survivors. The current treatments available for PC are advanced and impressive, but with such remarkable survival rates and prevalence, one must step back to evaluate the QoL in survivors. The physical side effects of PC treatment correlate strongly with the potential for a significant psychological impact in terms of altering self-image in relation to masculinity, depression and anxiety and psychosocial impact related to sexual functioning changes. Current research such as the ProtecT trial found differences in the side effects of radical prostatectomy in comparison with radiotherapy, with men undergoing surgery more likely to experience problems with sexual function and urinary incontinence, with men undergoing radiotherapy also having sexual functioning problems and bowel incontinence. Reference Bruce5 A future comparative study including ADTs should be conducted to help with patient treatment decision-making, and to tailor future information and advice for patients depending on the treatment chosen.

Throughout the literature, patients commented on how they would have felt better prepared for side effect presence if they had been given more comprehensive, tailored information and support. Sexual functioning side effects were commonly reported to have not been explained in a thorough manner, with limited information provided to patients. Appropriate information giving is therefore fundamental to ease the psychological burden of sexual dysfunction which can, in turn, lead to men’s changing perceptions of their masculinity, and lead to anxiety and depression. A suggestion could be for oncologists and healthcare professionals to take a more comprehensive information giving approach, as well as being open and honest when discussing sexual functioning changes post-treatment. Encouraging openness can also find out more from an individual, and as identified in the literature, the severity of psychological impact on patients vary from individual to individual, and an individually-tailored care plan would best support patients post-treatment. The treatment consent process could also inform patients of the heightened risk of psychological conditions developing as a result of the physical side effects that can persist post-treatment, so support can be accessed at a patient’s earliest opportunity, as well as raising awareness of the normality of experiencing such psychological changes such as anxiety and depression post-treatment.

Prostate cancer patients are more at risk of anxiety and depression than men of similar age, but it would be wrong to assume all PC patients will suffer from psychological symptoms. Although psychological changes were reported in all studies, not all survivors were negatively impacted by PC and treatment. Some patients had the ability to turn their journey into a positive experience, and much could be learned from these men to help others who may struggle post-treatment. It would be beneficial to do a form of qualitative research on this cohort such as a focus group to identify coping mechanisms or access to support to better understand how healthcare professionals can help support those who may be struggling. Future studies must investigate the exact prevalence of patients affected psychologically by treatment to fully understand the severity of these psychological side effects and to potentially reframe national agendas to ensure patients are fully supported.

Some of the literature interpreted their results as being potential predictors of those who may be most probable to suffer from depression and anxiety following treatment. A large comparative study of patient-reported outcomes would help reveal if different treatment modalities had differing psychological impacts to identify a treatment modality that makes survivors more at risk. Having predictors would give healthcare professionals an awareness to ensure patients have support in place to help manage potential psychological changes. Based on the studies reviewed, a checklist could be created to help identify at-risk individuals based on the summary of results included in Table 3.

The need for treating all patients as individuals has previously been highlighted, due to differing sociodemographic data and different treatment side effects and severity, this can impact on patients psychologically differently. The feasibility of assessing the psychological impact of all PC survivors is not realistic due to the overstretched NHS for budget and resources, thereby utilising the research, predictors of at-risk individuals are more representative to target specific PC survivors. Risk checklists could be a formative way to assess patients before they start treatment to highlight those at risk based on sociodemographic data, and post-treatment questionnaires should be used to assess side effect presence and severity; patients highlighted as at risk in each of these groups should be directed to relevant support. Support can take different forms, and with PC patients, it is important more research is conducted to see which support patients would most utilise, or a range of support options should be available to suit the individual.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Catherine Holborn, MSc, Sheffield Hallam University, for being my dissertation supervisor throughout the write up of this clinical review, as well as Heather Drury-Smith, MSc, Sheffield Hallam University, for her continued support transforming this dissertation into a publication.

Financial Support

No financial support, self-funded.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare none.

Appendix 1 Data Extraction Table