Introduction

From a legal and economic perspective, the global financial crisis, terrorist attacks, wars, natural catastrophes, and COVID-19 all have one thing in common: they potentially count as ‘material adverse change’ events. Such events are unpredictableFootnote 1 and have severe consequences for the global economy. To help manage the fallout from such negative events, businesses in economically valuable and complex deals, such as debt financing or mergers and acquisition (M&A) agreements, include special contractual risk allocation provisions, called Material Adverse Change/Effect (MAC)Footnote 2 clauses.

In commercial debt financing agreements, MAC clauses typically give the lender (or multiple lenders in syndicated financing) two options.Footnote 3 First, they enable the lender to refuse to make further advances of finance to the borrower.Footnote 4 Secondly, MAC clauses allow the lender to cancel the commitment to lend (ie termination of the facility, though often not of the contract itself) and accelerate repayment.Footnote 5 They allow the lender to exercise both options without incurring damages, upon the occurrence of typically unforeseen events that significantly undermine the objective for entering into the transaction.

These rights of the lender – to refuse to lend further or to demand early repayment – allow the lender to renegotiate the financing agreement by waiving the potential breach of the MAC condition.Footnote 6 Such an option for the lender can be expressly included in the agreement. More often, however, the ability of the lender to renegotiate comes on the basis that it can threaten to exercise its rights if there is no negotiated agreement.Footnote 7 When the prospects for business are dark, these functions of MAC clauses are relied on to avert disaster.Footnote 8

The law-and-economics effects of MAC clauses in debt finance, however, have been largely overlooked both in law and in finance. The existing influential literatureFootnote 9 has predominantly focused on the use of MAC clauses in M&A agreements but has been silent on the important matter of the effects of MAC clauses in debt finance.Footnote 10 This paper is the first to examine the pre-contractual (ex-ante) and contractual (ex-post) law-and-economics effects of MAC clauses in commercial debt financing agreements. This paper aims to answer the following question:

Why, in addition to precisely drawn conditions and covenants, including financial covenants, would the lender need to rely on vague and uncertain MAC clauses in commercial debt financing agreements?

Thus, this paper studies the efficiency of MAC clauses in debt finance. The need for such research is illustrated by the fact that major financing agreements have an immediate impact not only on the contracting parties but also the other market participants, employees, customers, and society.Footnote 11 The importance of studying these effects of MAC clauses in debt finance is further reinforced by the COVID-19-driven crisis which – arguably as a material adverse change – has highlighted the significance of these clauses for debt finance and M&A.Footnote 12

1. Scope, methods and findings

This paper examines the effects of MAC clauses in debt finance with regard to their functions as a condition precedent to both initial and subsequent borrowing and as an event of default. The significance of MAC clauses can be explained by studying their role in commercial debt financing contracts. To investigate these, the paper proposes a novel Multifunctional Effect Approach of MAC clauses in debt finance (the Multifunctional Effects Approach), which relies on a combination of solution-based economic theories that aim to explain the potential effects of MAC clauses (as discussed later). The paper argues that, apart from acceleration of the credit facility, MAC clauses have various ex-ante and especially ex-post beneficial effects. This paper aims to explain the misunderstood and unrealised nature of MAC clauses in debt finance and emphasises their potential role in orchestrating financing deals and linked relations (ie those beyond the immediate financing deal).

The paper finds that it is the ex-post functions of MAC clauses that are most observable in practice. Of those functions, some overlap with covenants (in particular, with financial covenants), which, coupled with other creditor protection mechanisms, such as representations and warranties, show the tendency of lenders to overprotect. Often such overprotection is technical and sometimes it is also beneficial for the borrower, as it makes the loan cheaper. Such lender overprotection could also cause creditor opportunism. What really distinguishes MAC clauses from covenants is their adaptive nature and the opportunity to initiate an early intervention. Financial covenants are tested periodically, whereas MAC clauses have no such requirement. Moreover, compared to covenants, which primarily address moral hazard, MAC clauses also aim to address uncertainty – they do not necessarily protect the parties from the risk; rather, they help to manage the fallout.

The existence of relational finance, the lenders’ reputation in the market, risk-decoupling strategies (such as loan transfers, hedging risk exposure), and increased market competition amongst different types of lenders all combine to force both types of lenders to be careful before accelerating finance on the account of a MAC as an event of default. Lenders are concerned about their market reputation and ability to attract new customers. This important feature of debt finance is primarily what makes MAC clauses application in debt finance different from their application in M&A (as discussed later). This potentially also explains why during both the 2008 global financial crisis and the ongoing COVID-19 driven crisis there was a spark of MAC litigation in M&A agreements, but few, if any, in debt finance. The potential application of MAC clauses in debt finance has thus not yet been fully realised. This significantly undermines the role and efficiency of MAC clauses in debt finance, as lenders rely on other seemingly more efficient contractual protection mechanisms to offset the risks.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows: Part 2 studies the common pre-contractual and contractual problems of debt financing deals, by presenting the framework of commercial debt financing agreements that commonly rely on MAC clauses. Part 3 introduces the Multifunctional Effect Approach and outlines the proposed effects of MAC clauses in debt financing. Part 4 examines the potential role of MAC clauses as ex-ante screening devices. Part 5 investigates the ex-post effects of MAC clauses outside and during financial distress. The final section provides a brief conclusion.

2. Problems of financing deals

This part highlights the negative effects arising from the information asymmetry and uncertainty problems for the debt financing parties and the corresponding costs on society's general welfare. The following analysis establishes the framework on which Part 3 relies to explain how MAC clauses could contribute to solving both issues – information asymmetry and uncertainty. Prior to identifying these problems, a diagram illustrating the scope of this paper is introduced.

(a) Scope and diagram of the financing deal

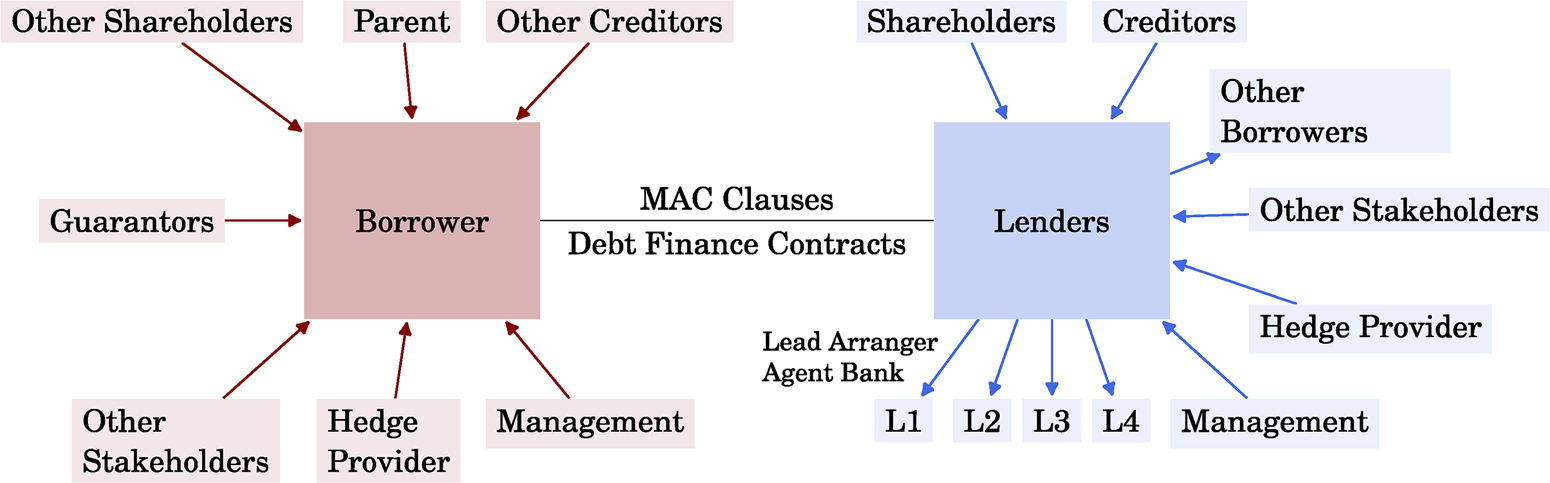

The analysis of MAC clauses in the context of commercial debt financing (term and syndicated loans) encompasses both non-investment grade borrower and an investment-grade borrower. On the lender's side, other than a typical example of a single lender, this network can additionally encompass a syndicate of lenders. Additional participants may include the borrower's parent company, its other shareholders, directors, guarantors, hedge providers, and other stakeholders. On the lenders’ side there may be the lenders’ shareholders, directors, its creditors, and the lenders’ or, typically, the lead manager/arranger, the agent bank, hedge providers, and other stakeholders. A diagram illustrating the relationships is supplied in Figure 1.

Figure 1. diagram of debt financing deal

Following the timeline of debt financing deals, problems that are relevant for the analysis of the effects of MAC clauses are shown in Table 1:

Table 1. timeline of the problems

Based on the types of problems of the financing deals, they could be presented as: (a) the main issues, between borrower and lender(s); and (b) the ancillary issues, between other corporate constituencies.

(b) Adverse selection costs and finance for lemons

The first issue that could be induced by information asymmetry is adverse selection (hidden information). In a debt financing deal, the information problem relates to the ability of the borrower to pay at the agreed date. This is an essential element for calculating the expected profitability of lending. From the perspective of the parties to the contract, adverse selection occurs if lenders do not possess essential borrower-related information.Footnote 13 From the market's standpoint, there can be a related ‘lemons’ problem. As a result of adverse selection, high-quality borrowers might be discouraged from obtaining financing, causing a potential collapse of such a market.Footnote 14

If we view lenders from the perspective of investors, the goal of a lender when evaluating the potential financing of a borrower is to calculate whether the borrower is a worthy investment. Often lenders succeed in gaining a sufficient amount of information to make a profitable investment decision. In many cases, however, lenders do not have enough information on applicant-borrowers. This could happen for several reasons, among which the most common is a borrower's reluctance to voluntarily disclose relevant information to the lender. Usually, it is in the borrower's interest to disclose information to achieve a low interest rate and less restrictive terms of financing. Yet such a full disclosure does not happen often. Potential reasons for not disclosing full information could result from the borrower's concern that the lender might: (i) not lend to it; or (ii) lend on more restrictive terms; or (iii) excessively monitor the borrower's activities; or (iv) later create hold-up problems for the borrower. Another question is whether the disclosed information is credible. Even in those situations when a lender investigates the borrower's stability and prospects, often lenders do not gain full access to information. This is not always efficient and practically possible owing to time restrictions and excessive transaction costs.

Adverse selection is equally important for those strong borrowers that are interested in dealing with established lenders.Footnote 15 This means that in situations where there is hidden information present, often strong borrowers will need an additional encouragement from reputational lenders to enter a business relationship with them.

(c) Moral hazard costs

The second issue that could be induced by information asymmetry is moral hazard (the agency problem or hidden action). Moral hazard more often arises at a contract performance stage.Footnote 16 The contractual parties often foresee the development of information asymmetries at an ex-post stage, even when at an ex-ante stage, they seem not to exist.Footnote 17

In a narrower sense an agency problem arises in a relationship or a contract that originates between two or more parties, where one party (the agent) acts for and on behalf of the other party (the principal or multiple principals).Footnote 18 Their relationship, therefore, requires a certain delegation of decision making to the agent.Footnote 19 In a wider sense an agency problem occurs in ‘almost any contractual relationship, in which one party (the “agent”) promises performance to another (the “principal”)’.Footnote 20

Opportunistic behaviour in a financing deal is more typically displayed by the borrower. Sometimes lenders will also have private conflicting benefits (eg whether to waive the borrower's default and renegotiate or not). This might cause the lenders to behave opportunistically (as discussed later). In debt finance, conflicts of interest issues are problematic not only for a wealth transfer from the lenders to the borrower but also since they generate overall efficiency losses as a result of potential borrower opportunism.Footnote 21 This adverse impact on the overall surplus should induce a unified interest of both the lenders and the borrowers to ex-ante prevent such opportunism.Footnote 22 As contractual counterparties outside the borrower's financial distress, the lenders face the problem of being disfavoured by the borrower due to its preference to act in the interests of its shareholders. Within financial distress, an additional problem arises for the lenders as to the conflict of interest and the wealth expropriation from one group of creditors to the other non-adjusting group.Footnote 23 This is the case when there is a conflict of interest between different types of creditors. These agency costs of debt are increased with the higher probability of the borrower's default.Footnote 24

If both adverse selection and moral hazard exist simultaneously, then lenders, as uninformed parties, face a challenge. If at least one of these issues is addressed at an ex-ante stage, arguably, the efforts of lenders with regard to contractual agency issues and, therefore, both ‘agency costs’Footnote 25 and ‘principal costs’Footnote 26 at contract performance stage will be minimised. This is because lenders will then have more information on how to tackle those. Although lenders might have an extensive market experience with regard to the type of the financing and the industry specifics, this will usually not solve all adverse selection problems. As argued in Parts 3 and 4, MAC clauses contribute to solving both issues.

(d) Endogenous and exogenous uncertainty

In a financing deal, it is important to stress the differences between the potential problems of moral hazard and adverse selection as a result of information asymmetry, and those problems resulting from endogenous and exogenous uncertainty. Uncertainty and systemic risks (both ex-ante and ex-post) do not necessarily imply opportunistic behaviour on the part of the borrower or the lender.Footnote 27 They are often caused by external market shock rather than internal deal-related borrower or lender opportunism.

The COVID-19 pandemic could be regarded as such an example, where it is the uncertainty in the financial markets and not (necessarily) moral hazard or adverse selection on the borrower's or seller's side that is the reason for potentially engaging MAC clauses, in debt finance and M&A agreements respectively. Although market uncertainty risks might arise both at the ex-ante and ex-post stages, for clarity, those will be analysed in the context of contract performance stage.

3. Multifunctional Effect Approach

This part identifies the ex-ante and ex-post effects of MAC clauses in commercial debt financing agreements that will then form the basis of the proposed Multifunctional Effect Approach. This novel approach aims to explain the potential efficiency of MAC clauses in commercial debt financing agreements. This approach relies on solution-based economic theories (eg transaction costs, information asymmetry, incomplete contracting, relational contracting, penalty default theory) to explain the potential effects of MAC clauses.

The paper uses this approach to study both theoretical and practical effects of MAC clauses and to explain the function of these effects, how they differ from those of covenants and where do these effects overlap with those of covenants. This approach aims to answer the question whether there is creditor overprotection in those cases where these effects overlap and why this overprotection is a problem in law-and-economic terms. The subsequent analysis is organised around the effects of MAC clauses as shown in Table 2:

Table 2. ex-ante and ex-post effects of MAC clauses

The aim of this approach is to provide a comprehensive theoretical explanation of MAC clauses and their role in debt financing agreements. The original contribution of the Multifunctional Effect Approach is in the following. First, unlike the common misconception that MAC clauses in debt finance exist solely for the benefit of the lenders, this approach identifies and expounds the potential advantages (gains) of MAC clauses for the borrowers, shareholders of borrowers, and its other corporate constituencies. Secondly, on the lenders’ side, it provides a broader explanation of the benefits and constraints of MAC clauses, not only for lenders themselves but also for their shareholders, creditors, and other counterparties. Thirdly, it explains the effects of MAC clauses both within and outside financial distress. Fourthly, this analysis also addresses the reputational, financial, and legal effects of MAC clauses. Fifthly, the approach focuses both on deal-centric (immediate) and market-related (synthetic) implications of MAC clauses in debt finance. It illustrates that the effects of breaches and financial distress due to MAC event of default in debt finance have wide implications, not only for the parties to the deals themselves but also for market participants and overall economic stability. Sixthly, this approach provides an explanation for the less frequent litigation (actual trial) of MAC clauses in debt finance in practice. It predicts a continuation of the existing trend of litigation hold-up in the future, justifying this with the factors of lender market reputation, the notion of repeat interaction in the financing world (rare in M&A deals), and the establishment of relationship lendingFootnote 28 between financing parties. Finally, it highlights and explains, where appropriate, the different natures of MAC clauses in debt finance and M&A deals.

4. Quality warranty and insurance premium: ex-ante effect

This part explores the ex-ante effect of MAC clauses. One might be tempted to think that the sole objective of MAC clauses, especially in debt finance, is in their role and effects during financial distress. This would be both too simplistic and ignore the economic reality behind them. The discussion is formed around the screening effect of MAC clauses, which contributes to countering ex-ante adverse selection.

(a) Screening via self-selection

Screening mechanisms are implemented to identify the informed party (eg potential borrowers) by presenting them with alternative contract terms for specific transaction.Footnote 29 This allows the uninformed party (eg lenders) to extract information on the borrower, their preferences, and their limitations, and forces the borrower to disclose information at an early stage of negotiations. This process of extracting information by the uninformed parties (eg lenders) has been termed ‘screening via self-selection’.Footnote 30 The instruments used for screening are referred to as ‘screening devices’.Footnote 31 By choosing one of the offered options that contain different terms, the informed parties (eg borrowers) are sorting themselves into respective categories of risk-bearers. Screening devices have been used in economics from various perspectives (screening via price and quantity,Footnote 32 screening via price and collateralFootnote 33) as a tool for the uninformed party (eg lender) to filter the informed party (eg borrowers).

(b) The test of screening

This section examines how in a competitive credit market environment the uninformed lender could differentiate between non-risky and risky borrowers.Footnote 34 The ex-ante screening mechanism is employed in the context of borrowers’ self-selection due to the screening effects of MAC clauses.

Often it is the lender who sends the first draft of the contract with a MAC package to the borrower. More often, it is lenders who suggest the first initial framework. This is usually conducted in the form of a term sheet at an earlier stage of the process, alongside a mandate letter and followed by a first draft of a facility agreement at a later stage. Often, however, it is difficult in practice to distinguish who initiates a certain action, especially given the long-term nature and timing of the negotiation process and the relationship between the parties.Footnote 35 The challenge that arises for a strong borrower at an ex-ante stage is how to credibly prove its quality to the lender and be viewed as a worthy project.

Although screening by examining (eg lender's due diligence) is the most common, simple way to screen out the informed borrowers, it is rather costly.Footnote 36 Despite certain access to information by the lender, the information asymmetry is not fully eliminated. Often full inspection is practically impossible in real life. Self-sorting via screening, for instance, via MAC clauses, is an alternative, more cost-efficient mechanism, performing a screening function of risk-tolerance categories of the potential borrower-applicants.

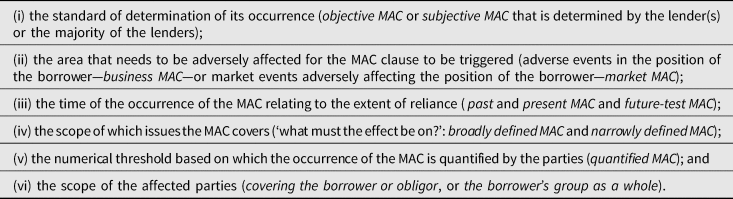

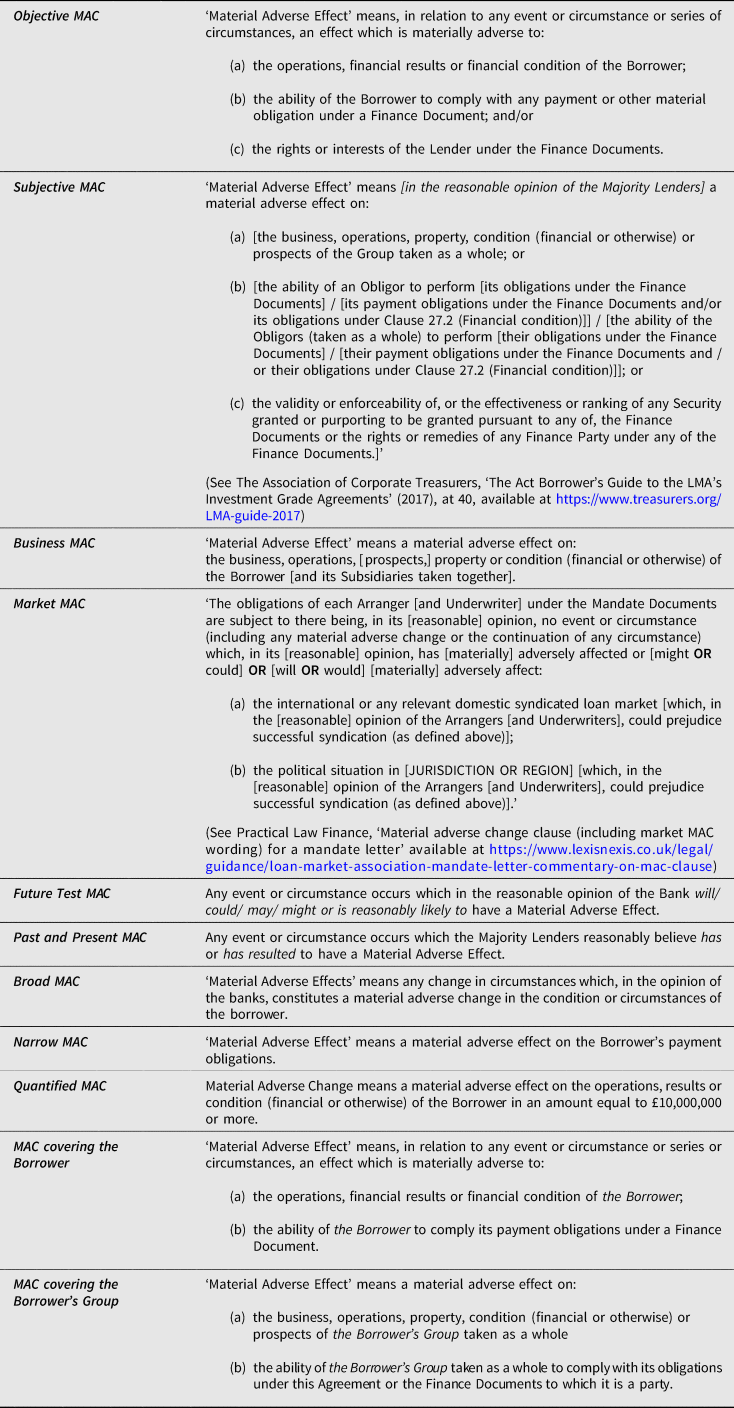

In financing agreements, the taxonomy of MAC clausesFootnote 37 that can be used for screening the different categories of borrowers can be presented as shown in Table 3 below. Some examples of MAC clauses are set out in Table 4.

Table 3. Taxonomy of MAC clauses in debt finance

Table 4. Examples of MAC clauses in debt finance

Taking the example of negotiating the test of determining the occurrence of MAC (eg subjective or objective) and the likelihood of its occurrence (eg future test MAC or past and present MAC), lenders could screen out different types of borrowers at the ex-ante negotiation stage. Usually, the MAC definition including a subjective determination test by the lender, or the majority of lenders, may be more favourable for the lender than the borrower. On the other hand, should the borrower find itself in an adverse position, it could be favourable for the borrower from the perspective that such a subjective decision shall be approved by the majority of the lenders of a consortium. Since there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach for the definition of the MAC, the riskier borrower will try to negotiate it as narrowly as possible, preferring the material adverse effect to be on the ‘financial condition’. Such a narrow definition arguably restricts the lenders’ discretion in determining what the ‘material adverse change’ may be.Footnote 38 The lender, in its turn, will opt for a broader category, insisting on terms ‘prospects’ or ‘condition’. If the provision of MAC as an event of default already includes an element of subjectivity, the borrower's objection to the inclusion of the subjectivity element in the definition of the MAC itself will be more successful. Moreover, in financing agreements, from the borrower's perspective, the higher the likelihood that the MAC will occur before the event of default is triggered, the better.

Hence, categorising and ordering the MAC in terms of the likelihood of a MAC, from the most favourable to the least favourable from the perspective of the risky borrower, could be as follows: ‘has’ → ‘will have’ → ‘is reasonably likely to have’→ ‘could be/have’ →‘may be’ → ‘might be/have’ a Material Adverse Change. From the lender's perspective the order would be the inverse: most likely is least favourable, least likely most favourable. Such self-selecting screening could be used to acquire information about the risk-tolerance of the borrower. In particular, as a result of screening borrowers’ types with MAC a separating equilibrium could be achieved, when the different types of borrower-applicants will interpret the screening function of MAC in a different way. In other words, the riskier borrowers will opt to negotiate both the definition of the MAC and its determination test differently from stronger borrowers. Such a distinction may help lenders to address some aspects of the adverse selection problem at a pre-contractual stage.

5. Debt governance: ex-post effects

This part analyses the potential effects that MAC clauses have at a contract performance stage both outside and during financial distress of the borrower. It does so by relying on the notion of debt (creditor) governance.

Unlike traditional corporate governance, debt governance has not been at the centre of attention for a long time.Footnote 39 With the introduction of innovative mechanisms (such as securitisation, and credit default swaps), the rise of professional expertise, intensified lender-competition, and an increased number of alternative credit providers, the situation has gradually changed. Debt governance, as a ‘missing lever’Footnote 40 of private corporate governance, has become essential not only for the private parties to the financing deals but also for the wider market participants and the overall policymaking.

Interactive debt governance theory illustrates the ability of lenders to monitor and detect managerial shirking.Footnote 41 It also demonstrates the beneficial role of the lender's exit decisions (via signal-exchange and collaboration on penalising management) for the other stakeholders.Footnote 42 In contrast to studies on debt governance that primarily focus on financial distress, those principally studying the lenders’ influence on debt governance outside of the borrower's distress suggest that private lenders overall demonstrate better information, incentives, expertise, and enforcement powers than the shareholders and thus better address managerial agency costs of debt.Footnote 43

The creditor's significant active role outside of the borrower's financial distress has also been tested empirically. Evidence from these studies indicates that efficient creditor control can promote equity-focused corporate governance or even replace it.Footnote 44 In the context of what constitutes debt governance, it is not only monitoring that is crucial, but also the concessions granted by the lender to the borrower.Footnote 45 Effective creditor protection and governance are also important for a lower cost of credit. It can also contribute to a greater accessibility to finance, increased creditor recovery, and to alleviating investor risk. The last of these, inter alia, also promotes greater financial stability.Footnote 46

Active debt governance, nevertheless, is not without its shortcomings. Excessive creditor control might aggravate conflicts of interests between shareholders and creditors.Footnote 47 Debt governance might also have a ‘hold-up effect’ on the borrowers.Footnote 48 This typically happens when creditors attempt to extract surplus value from the borrower by granting waivers and requesting monetary compensation (amendment fees) or when they increase the charges above the initially agreed interest rate. The benefits and drawbacks of debt governance and its relevance to MAC clauses form the discussion basis of the following sections (a)–(g).

(a) Bonding, incentivising, and disciplining the borrower

This section identifies the bonding (restricting), incentivising, and disciplining functions of MAC clauses in debt finance. First, it examines how MAC clauses potentially contribute to solving information asymmetry problems between the borrowers and lenders. Secondly, it investigates how MAC clauses could be useful to borrowers’ other corporate constituencies, for instance, borrowers’ guarantors or other creditors. It thus mainly focuses on the moral hazard by the borrower and the relevance of MAC clauses in countering the borrower's potential shirking and value-reducing behaviour.

The opportunistic behaviour of borrowers can be present at the ex-ante stage. This typically happens when the low-quality borrower is induced to misrepresent its quality. It can also arise at an ex-post stage, when the borrower tries to behave opportunistically. In rare cases complete monitoring by lenders could be possible, offering a ‘first-best solution (entailing optimal risk sharing)’.Footnote 49 Very often, however, full information on actions of the borrower is difficult or impossible to identify, and monitoring costs may contribute to this problem.Footnote 50 Compared to non-bank lenders, such as alternative credit providers, commercial banks have more expertise in collecting relevant information and monitoring borrowers. Thus, when the borrower has both types of lenders, non-bank lenders free ride (rely) on these less costly interaction-abilities of banks for monitoring and renegotiating.Footnote 51

As a contingency in the financing agreements, MAC clauses have a direct effect on the renegotiation design. They impact the outcome of renegotiation due to their influence on the default outcome and the allocation of bargaining power. MAC clauses could be relied on as a threat of exit to intervene in the borrower's governance as mechanisms for refusing to lend further or accelerating financing. These threat-of-exit or governance (voice) functions of MAC clauses could be used ‘not only to redress slack but also to obtain a favourable renegotiation of the lending terms’.Footnote 52

Renegotiating the terms of financing by relying on a MAC event could also be a useful signal to other stakeholders, such as company's guarantors or other business counterparties. It also contributes to the dynamic completion of the financing agreement and allocation of the control rights ex-post.Footnote 53 As a result, such renegotiation has implications on the adverse incentives of the borrower and influences the contract security design. MAC clauses also represent the borrower's promise made to the lenders not to undertake value-reducing actions or enter into debt diluting transactions to a significant extent. These effects constitute the restricting-bonding function of MAC clauses. By prohibiting itself to exercise value-reducing actions ex-post, the borrower decreases its default probability and increases its borrowing capacity ex-ante.

Additionally, four kinds of disciplining effects of MAC clauses can be distinguished. First, the threat of refusing to lend (or to lend further) or exercising a MAC event of default, as a ground for renegotiating or accelerating the financing agreement, constitutes a broader de facto transfer of control rights in favour of the lender.Footnote 54 Secondly, MAC as an event of default could have a negative effect on the borrower and could be used as a penalising element in its future dealings or even pose a threat to the existence of the company.Footnote 55 The empirical evidence suggests that when the creditors share default information about their clients it has a strong adverse effect on the borrower, acting as a disciplinary device.Footnote 56 The borrowers in this scenario will be more incentivised not to breach, in contrast to the situation where creditors share not only the relevant default information but also all the characteristics of the borrower. Since the implications of default sharing are negative even for technical defaults, the penalising force of such an information-revealing regime is, thus, stronger for MAC clauses. Thirdly, the disciplining effect of MAC clauses also helps to build a reputation. This in turn requires less monitoring effort from the lenders. Finally, the existence of the potential MAC as a cross-default is an important factor in the MAC's nature of revealing information and incentivising cooperation between the lenders and the borrower. The danger of such a cross-default or cross-acceleration is that it might have a domino effect in the market. Not only do MAC clauses have an impact on the effective or excessive creditor governance, but they also have a significant influence on the value of renegotiation and trust-building between the lenders and the borrowers.

(b) Tackling uncertainty and filling in gaps

One of the important effects of MAC clauses in debt finance is their function to tackle uncertainty, particularly to manage the economic fallout arising from uncertainty. This feature of MAC clauses is what also makes them different from precisely drafted financial covenants.

In a debt finance context especially, MAC clauses are drafted more commonly in the form of a standard, as opposed to rule, that requires ex-ante drafting efforts.Footnote 57 In this respect, they could be contrasted with those in M&A, where the trend of drafting MAC clauses with carve-outs (exceptions to the definition of MAC) and often also carve-outs to the carve-outs (exceptions to those exceptions) has assigned them some rule-like characteristics. The standard-like attributes that MAC clauses have in debt finance provide a response in filling the gaps and countering contractual incompleteness.Footnote 58

In many cases, the borrowers and the lenders are unable to describe all the possible future situations of their relationship and how it will be affected. This is the notion of incomplete contracting. Contracting parties may rely on a vague language or accidentally overlook a problem due to bounded rationality.Footnote 59 They do not write complete contracts because of transaction costsFootnote 60 or because of the difficulty of predicting future events. A contract could also be incomplete because of information asymmetry between the parties.Footnote 61 In certain cases, writing a complete contract is precluded because of the parties’ anonymity (pooling).

In the context of incomplete contracts, MAC clauses offer both ex-ante and ex-post contractual protection. In a financing agreement they help manage the fallout from negative events caused by uncertainty. These effects of MAC clauses are different from their effects with regard to moral hazard and adverse selection. The example of COVID-19 illustrates that the negative events affecting companies were often caused by market uncertainty. In many cases it involved neither moral hazard nor adverse selection by the borrowers. Rather, the economic fallout of many companies was due to unforeseen exogenous market risks beyond the control of either of the parties. Unlike financial covenants, which are tested periodically, MAC clauses, with their adaptive nature, provide lenders with the opportunity to react to unforeseen events quickly and, if necessary, to initiate a dialogue with the borrower.

In case of uncertainty, the problem for the parties arises not necessarily because of the borrower's opportunism, but instead because of the absence or insufficiency of important information at the initial contracting stage of the financing. MAC clauses aim to address those future events that are either impossible to foresee or too costly to estimate because of transaction costs. This function is especially helpful at a contract performance stage, prior to renegotiating the agreement.

The importance of addressing uncertainty through MAC clauses also has interesting implications for the parties’ incentives and contractual renegotiation design. Goshen and Hannes find that when the principal is competent, it becomes less efficient to rely on courts to address the incompleteness problem as compared to extra-judicial conflict resolution techniques.Footnote 62 This finding could also explain the infrequency of MAC litigation in debt finance. In general, lenders, as principals, are competent and have the expertise and reputation to handle problematic situations.

In short, first, MAC clauses fill in the gaps in incomplete contracts – a function that also distinguishes them from covenants, due to their adaptive nature. Secondly, because of their evolving nature, and unlike financial covenants, which are commonly tested periodically, MAC clauses provide the lender with the opportunity to initiate renegotiation or refuse to lend further to the borrower earlier than might happen when relying on financial covenants. Thirdly, by addressing the uncertainty, MAC clauses facilitate renegotiation of the contract and efficient allocation of decision rights ex-post. Such an assignment of decision rights helps to solve problems of incompleteness.

(c) Restructuring function of MAC

When the defaulted borrower company is cash-flow insolventFootnote 63 but is still economically viable, rehabilitating the borrower is typically more desirable not only for the borrower itself but also for its creditors and usually society.Footnote 64 In such cases, a contractual settlement could be the optimal solution. It is submitted that MAC clauses in financing agreements have a private (contractual) restructuring function. MAC clauses function as a de facto private (contractual) debt restructuring regime bargained for by the parties. Unlike financial covenants, they provide an opportunity to initiate the contractual restructuring earlier, if needed. This is because, unlike with financial covenants, there is no periodic testing timeframe for MAC clauses.

Among the motivations for considering a private resolution mechanism (as opposed to mandatory state-dictated procedures) after the occurrence of financial distress, are the following: (i) the ban on contractual bankruptcy regime aggravates underinvestment, unlike a bankruptcy contract, which could potentially mitigate underinvestment;Footnote 65 (ii) although there are many lenders who might have heterogeneous preferences and who do not necessarily lend simultaneously, the contracting parties could organise their bankruptcy contracts;Footnote 66 (iii) additionally, when drafting legal rules legislators should consider the parties’ competence to contract on bankruptcy matters.Footnote 67

The ex-ante stage in the lending process represents the contractual bargaining and the ex-ante costs of insolvency. By being permitted to privately contract due to a MAC event of default, as opposed to using those procedures presented by the state, the parties to debt financing agreements could alleviate two ex-post agency costs of debt: (i) inefficient delay of insolvency of an insolvent firm, and (ii) adopting the procedure in favour of managers of the company rather than optimising returns to creditors.Footnote 68 In this regard, MAC clauses are connected to the Creditors’ Bargain theory,Footnote 69 viewing bankruptcy through the lens of bargaining between the lenders and the borrower.

MAC clauses in debt finance offer four perspectives to the contractual versus state-supplied insolvency regime discussion. First, they could be viewed as an early warning signal (protection) for creditors. Other, weakly adjusting, or non-adjusting, creditors could free ride on the contractual effects and protection offered by MAC clauses. This will also save on their monitoring costs.

Secondly, should things go wrong on the borrower's side, the lenders have an option to leverage the borrower into renegotiating the financing agreement. This solution, offered by MAC clauses, generates a private restructuring impulse for those borrowers who are in financial trouble, but fall short of insolvency. By including MAC clauses in the financing agreement, the parties contractually create an incentive for a rehabilitation procedure that could be beneficial ex-post and induce the borrower to choose efficiently. By choosing to renegotiate rather than terminate the loan on the occurrence of a MAC event of default both the lender and the borrower benefit. For the borrower, such a contractual restructuring could save it from potential cross-defaults or cross-acceleration under other financing arrangements. For the lender, the advantages of renegotiation in reliance on a MAC clause are twofold. It provides strong leverage over the borrower because the lender exercises its voice (ie the lender ‘forgives’ such a default) rather than using it to exit the relationship. This, arguably, incentivises the borrower to facilitate its recovery. This restructuring option could potentially have a beneficial impact also for other lenders who choose to restructure instead of racing to collect. Furthermore, the non-adjusting (involuntary) creditors can free ride on the functions performed by strong creditors and rely on the latter's decision to renegotiate via a MAC clause as an information screen. This will result in positive externalities for the non-adjusting creditors. On the other hand, such a private restructuring could be to the disadvantage of certain types of creditors (negative externalities).

Thirdly, if the private restructuring regime proves to be sub-optimal, the lenders have the option to rely on the MAC as an event of default and accelerate the facility. This termination might adversely affect not only the borrower but also the lenders and their market reputation. The mere occurrence of a MAC as an event of default in financing agreements does not necessarily entail insolvency proceedings. However, given the reputation concerns and the market expertise of the lender, an acceleration of the loan on the account of the MAC as an event of default can be a potential signal for the borrower's insolvency or severe financial distress.Footnote 70 This signal of MAC could be alarming not only for sophisticated lenders but also for involuntary creditors.

Fourthly, the cross-default effect of MAC clauses should be considered. Unlike a cross-default of technical defaults (eg maintenance covenants), cross-default on the account of the MAC acts as a nuclear weapon for the creditors’ race to collect. This is because the high threshold for proving MAC, coupled with its deal-centric implications (legal, financial, reputational risks) and market-centric implications (cost of finance, lender competition, contract drafting, enforcement) makes such a cross-default option a weapon of last resort. The possibility of cross-default affects the conversation between the lender and the borrower, and especially the borrower's incentives.

This restructuring function of MAC clauses is also different from technical or manufactured defaults related to covenant provisions. Although the latter could motivate the contractual parties to amend the terms of financing, they do not amount in their essence and magnitude to the substantial rehabilitation of the on-the-edge borrower. Moreover, the contracting-about-distress function of MAC clauses also potentially explains the prevailing absence of litigating debt financing agreements based on the MAC as an event of default.

(d) Countering creditor opportunism, solving overprotection, or stimulating balance?

MAC clauses contribute to countering borrower opportunism and also, in certain instances, to creditor opportunism. This section identifies the relevant patterns of creditor opportunism and overprotection and investigates the role of MAC clauses in addressing these issues. By doing so it also aims to highlight the beneficial role of MAC clauses for the borrower and other corporate constituencies, as distinct from their more typical role of favouring lenders in financing agreements.

One explanation for the infrequency of MAC litigation, especially in debt finance, could be the lenders’ diversification of risks and monetary satisfaction from the borrowers’ default via the credit default swaps (CDS).Footnote 71 Such risk-decoupling by lenders is in addition to their extraction of wealth from the borrowers via the contractual waiver mechanism for breaches.

On the one hand, there could be a clash between the renegotiation route through a potential MAC event of default and the lender's private benefits arising from CDS. This is because it could be socially optimal to renegotiate the financing agreement on account of a potential MAC event of default, especially in situations that do not necessarily involve borrower-opportunism but where the renegotiation is mandated by uncertainty in the markets. In these situations, overprotected, less incentivised lenders (‘inefficient empty creditors’)Footnote 72 often refuse to renegotiate with borrowers to collect their CDS payments, even when renegotiation via contractual out-of-court restructuring would be the socially beneficial alternative.

On the other hand, MAC clauses and CDS are creditor protection mechanisms against the borrower's default. Both require a charge of an insurance premium and play an important role in times of borrower financial distress. Despite this, there are several differences between them. First, MAC clauses in debt financing agreements involve a private borrower/lender (direct) relationship. In contrast, despite its contractual nature, CDS is of a more public nature. It covers a lender/hedge-provider relationship and, in the case of a ‘naked CDS’, a hedge-provider/speculator (synthetic) relationship.

Secondly, unlike MAC clauses, CDS does not have an important role outside the borrower's financial distress. The exception to this could be the signalling function of the hedging prices of the borrower when the borrower hedges its economic risk. It is argued that lenders could rely on the hedging mechanism (eg the borrower's hedging prices) to monitor the borrower's situation. The contract specifications of borrower's hedging could be used as an information revelation mechanism for the lender. It could be used as a precaution on its own but could also be an early warning signal for either renegotiation of the financing agreement on the grounds of a potential MAC event of default or contribute to the establishing of the actual MAC event of default. Often hedging agreements, in particular the borrower's hedging price, will be more important in terms of a lender's ability to monitor moral hazard by the borrower than some of the information covenants that the borrower provides the lender in the covenant-lite agreements. Derivatives are additional monitoring mechanisms that could act as an early signalling tool for the lender in establishing a MAC as an event of default or as a potential event of default for renegotiating the terms.

Thirdly, while the lenders could rely on technical defaults (eg financial covenants) to trigger the benefits of the CDS, they cannot as easily seek to rely on the MAC event of default as an opportunity to gain private benefits. Relying wrongly on a MAC event as a basis for leveraging to renegotiate or terminate could be disastrous for the lenders themselves. This is because the risk of high reputation damage because of wrongful acceleration on the account of the MAC event of default might stop opportunistic lenders and incentivise them to renegotiate – preventing the inefficient liquidation of the borrower. This effect of MAC clauses could be beneficial in the context of addressing ‘faux defaults’ (artificially manufactured technical defaults).Footnote 73 Faux defaults benefit the lender, which can subsequently extract benefits from its CDS arrangement because of the borrower's default. In some cases, the manufactured technical defaults could also be a result of a dishonest arrangement between the contracting parties, whereby the borrower, for instance, agrees to intentionally default, subject to receiving more funding from the lender.

The problem associated with opportunistic lender behaviour due to the risk-decoupling effects of CDS is not only that it creates negative implications for the borrower company – by not allowing it to renegotiate or by forcing it into inefficient liquidation – but also that ineffective liquidation often causes negative externalities on the financial system as a whole.Footnote 74 The difficulty in preventing faux defaults, due to the fact that they are speculative and can be played by deceitful lender-borrower cooperation, does not apply to the MAC event of default. Arguably, MAC clauses could help to solve this empty creditor problem and thus facilitate a market for debt governance. The risk and the cost of wrongful acceleration in reliance on MAC clauses with their negative implications should discourage opportunistic lenders from pursuing the CDS route as a way of earning money. Overall, the features of MAC clauses in debt finance and their connection to CDS and risk decoupling differentiate them from MAC in M&A.

Nevertheless, CDS also has advantages: it helps those riskier firms that would otherwise not have received finance to get access. CDS makes the financial markets more efficient and thus enhances capital allocation.Footnote 75 It provides a creditor with the opportunity to protect against the borrower's default with fewer transaction costs and more accuracy. The relationship between the CDS and MAC could also be viewed as one complementing the other, where MAC clauses help to balance the benefits of the CDS while simultaneously also preventing creditor opportunism.

The second explanation for the infrequency of MAC litigation in debt finance is the ability of lenders to transfer loans.Footnote 76 When making financing decisions lenders provisionally calculate the riskiness of the borrower in their cost of finance. Lenders interested in minimising their risk exposure from the default of an individual borrower might look for techniques to transfer their loans and diversify their risk.

Unlike CDS, which allows lenders to hedge their economic exposure, some loan transfer mechanisms (eg assignment or novation) – but not all (eg sub-participation)Footnote 77 – enable lenders to cease their relationship with the borrower.Footnote 78 Such a risk diversification strategy might affect lenders’ incentives and the extent of involvement in monitoring the borrower.Footnote 79 In the context of the application of MAC clauses, this additionally raises the question of socially optimal renegotiation of the financing agreement in reliance on a MAC event and lenders’ incentives to transfer the loan. This also touches upon an important tension between ‘the right of the borrower to prevent or limit the transfer of the debt and the right of lender to alienate its own property, namely the debt or the proceeds’.Footnote 80

(e) Establishing relationship lending

By facilitating debt governance both within and outside the borrower's financial distress, MAC clauses contribute to establishing relationship lending between the lenders and the borrower.

Compared to transactions, among the characteristic attributes of relations are their: (i) internal capacity for growth and change; (ii) dependence on further cooperation and continuous further planning of substantive activities; and (iii) consideration of trouble as expressly or tacitly demonstrated as an aspect of normal life.Footnote 81 Relational contracts are used when, for various reasons, ‘writing a complete, state-contingent contract is either impossible or impractical’.Footnote 82 They regulate a continuing relationship.Footnote 83 In relational contracts the imposition or threat of enforcing relational or informal sanctions, such as termination of financing or discontinuation of business relation or trade, induces promise-keeping.Footnote 84 The effectiveness of these sanctions has been explained on the basis that legal sanctions ‘form the information basis for unleashing relational sanctions’.Footnote 85 Relational finance concentrates specifically on the essence of the debtor-creditor relationship. It incentivises the creditor to ensure beneficial financial coordination and control, with the derived gains accumulating to all stakeholders.Footnote 86

The information-revealing effects of MAC clauses incentivise the borrower to act in a value-maintaining manner, while simultaneously holding back the opportunistic lender from damaging the ongoing relationship. They also help to build trust between the parties and provide both with the opportunity to either establish or improve their market reputation. Trust in a lending relationship provides the possibility to access financing at a cost that is not affected by prior defaults.Footnote 87 Although a term loan (or a syndicated loan) might seem to fall into the transactional category, the long-term nature of the loan might cause various relational aspects to emerge.Footnote 88

These relational effects of MAC clauses are beneficial both for the lenders and for the borrowers. Lenders are attracted to investing in relationship lending and collecting client-related valuable data, as this will put them ahead of their less-informed competitors. It also enables them to continue lending to those firms with which they have established a relationship, despite having previously lent a large amount of money, since lenders can limit their risk through various risk-diversification techniques (eg CDS).Footnote 89 This relational aspect is especially true in private debt agreements, which are often structured based on the previously existing lender-borrower relationship.Footnote 90

For borrowers, it is beneficial to work with a relationship-lending partner due to such lender's better knowledge of the specifics of its business. Relationship lending helps parties to overcome information problems and minimise the social costs that are connected to financial distress. It also helps to reduce moral hazard, as with the repeat of the situation the ‘dysfunctional behavior is more accurately revealed’.Footnote 91 The potential problem in establishing relationship lending is that it also produces informational monopoly that might have a hold-up effect on the borrower. This is because a relational lender will be able to offer financing on better terms than other potential new lenders.

This feature of MAC clauses in financing agreements is not present in their application in M&A agreements. Compared to financing agreements, M&A transactions are typically one-off transactions. Such a difference is one more example of the different applications of MAC clauses in debt finance and M&A.

(f) Serving as a penalty default rule?

From a functional perspective MAC clauses potentially operate as a penalty default rule. By incorporating them in financing agreements, the objective is to incentivise parties (typically the borrowers) to reveal information and to take precautions against risks.

The penalty default rule theory – describing how courts and legislative bodies should develop default rules – was coined by Ayres and Gertner.Footnote 92 According to this theory, instead of incorporating default rules that the parties would have preferred had they had time and money to draft a complete agreement, in certain circumstances the penalty default rules should be more appropriate.Footnote 93 Penalty default rules are those default rules that the parties would prefer to refrain from using, due to their penalising nature.

From a functional perspective, the notion of the penalty defaults best explains the role and implications of MAC clauses in debt finance.Footnote 94 Unlike immutable rules which cannot be contracted upon, MAC clauses as default rules are incorporated into the agreements to govern the contractual relationship, unless the parties contract around them.Footnote 95 Such information-forcing rules are useful and reasonable in the presence of information asymmetry. MAC clauses act as a penalty default rule in financing agreements for the more informed party, typically the borrower, by incentivising it to reveal information to the uninformed party, usually the lender. When the objective of the MAC penalty default rule is to inform the ‘relatively uninformed contracting party [the lender], the penalty default should be against the relative informed party [the borrower]’.Footnote 96 MAC clauses also encourage both the borrower and the lender to reveal already known information to third parties, for instance the courts.

The idea behind including MAC clauses in financing agreements is to encourage the party that does not want to reveal information (ie the borrower), to reveal it for strategic purposes. Although the penalty default is usually employed in this context against the borrower, sometimes it will be possible to implement the MAC penalty default rule against the lender, specifically to force the lender to reveal the risk to the borrower or to take precautions against it. This is because the lender is in the best position to protect itself from foreseeable risks. The incorporation of MAC clauses, with their information-forcing function, allows the less informed party (typically the lender) to take precautions by more engagement with the borrower. These preventive measures will also be beneficial to other lenders of the borrower, and in this way, arguably, also for society more generally.Footnote 97

Although MAC clauses are not statutory mechanisms, from a functional perspective they could still be regarded as an example of penalty default rules for the following reasons. First, the notion of penalty default rules applies not only to statutes but also to common law developed default rules.Footnote 98 As illustrated by the case law on MAC clauses, judges interpret MAC clauses functionally similarly to penalty default rules.Footnote 99 Secondly, for the ‘stickiness’ argument of penalty default rules MAC clauses are usually the norm rather than the exception. They are often incorporated in the LMA standard documentation. This almost mandatory incorporation of MAC clauses in financing agreements is often true even in the case of covenant-lite leveraged credit agreements. Incorporation and contracting around penalty default MAC clauses give rise to different types of contractual pooling and separating equilibria, therefore minimising the inefficiency of strategic pooling.Footnote 100

Developing the MAC penalty default rule with case law will be the optimal route. Only upon a sufficient advancement of case law could the transformation of MAC clauses into statutory form be an option. Nevertheless, even without the incorporation of the MAC penalty default in the legislation, the business practice of relying on MAC clauses is the norm; the recent developments of COVID-19 will make the application of MAC clauses even stickier. The penalty default rationale of MAC clauses has been developed through case lawFootnote 101 and is still in its initial stage. More MAC-related litigation is needed to better develop this rule. This does not mean, however, that one cannot develop the penalty default rationale of MAC clauses through precedents, then make it statutory and further continue its development through case law.

(g) Exit: signalling with acceleration

Having examined the ex-post effects of MAC clauses outside of the borrower's severe financial distress, this section focuses on analysing the ex-post effects of MAC clauses during the borrower's severe financial distress.

As examined in Part 3, MAC clauses have ex-ante screening effect. From a different angle, MAC clauses also have ex-post signalling effects in times of borrowers’ financial distress. A lender's ex-post decision to accelerate a loan due to a MAC as an event of default could be analysed as a strong signal to the market that there is something wrong with the borrower.

The famous practical example of such an acceleration based on a MAC event of default under English law is BNP Paribas v Yukos Oil. Footnote 102 In this case the multi-million dollar syndicated facility was accelerated by the agent bank on the ground that there had been a MAC event of default (among other defaults) by the borrower. Shortly after the acceleration by the syndicate, insolvency proceedings were initiated against the borrower, resulting in the liquidation of the company.

Given the significant transaction costs, as well as the reputational, legal, and financial risks arising as a result of the uncertainty and the high threshold involved in litigating a MAC event of default, the borrower's decision to litigate could also be interpreted as a signal of the borrower's strong quality. Arguably, it is often a courageous borrower who would make the alleged position of its materially adverse financial distress public, were it not confident that the lender had wrongfully terminated financing. Looking at the experience of buyers or sellers in litigating MAC in the context of M&A deals in the majority of litigated US and English cases, those sellers that have litigated a MAC were successful in proving its non-occurrence. By litigating the occurrence of a MAC event, a strong borrower might also achieve a renegotiation of the financing terms.

Conclusion

The pre-contractual (ex-ante) and contractual (ex-post) effects of MAC clauses in debt finance have been largely overlooked, both in law and in finance. This paper is the first to study these law-and-economics effects of MAC clauses in commercial debt financing agreements. To this end it proposed a novel Multifunctional Effects Approach of MAC clauses in debt finance. The paper relied on this approach to explain that apart from the termination of facilities MAC clauses have various other effects.

First, the paper argued that MAC clauses have beneficial ex-ante and ex-post effects that could be relied on not only by lenders but in certain circumstances also by borrowers and other corporate constituencies. It studied the ex-ante screening effects of MAC clauses in debt finance. Secondly, the paper argued that MAC clauses also have various contractual effects that should not be limited to the information asymmetry problem: the paper suggested that MAC clauses also play an important role in improving governance, decoupling debt, providing restructuring impulses, countering uncertainty, potentially, having the effect of a penalty default rule, and having signalling effects.

The paper concludes that it is the ex-post functions of MAC that are more observable in practice. From those functions, some overlap with covenants, which, coupled with other creditor protection mechanisms, show the tendency of lenders to overprotect themselves. Often such overprotection is technical, but in certain cases it could cause creditor opportunism. What really distinguishes MAC clauses from covenants is their adaptive nature. Compared to covenants, which primarily address the renowned moral hazard issue, MAC clauses also aim to address uncertainty – they do not necessarily protect the parties from the risk, rather they help to manage the fallout. They initiate renegotiation and, in this way, help to reduce both the costs to the parties and the social (welfare) costs to society. Additionally, covenants do not address creditor opportunism, unlike MAC clauses.

The existence of relational finance, the lenders’ reputation in the market, risk-decoupling strategies, and increased market competition amongst institutional and non-institutional lenders force both types of lenders to be careful before accelerating finance on account of a MAC as an event of default. This important feature of debt finance is primarily what makes MAC clauses in debt finance different from their application in M&A. This potentially also explains why during both the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 crisis there was a spark of MAC litigation in M&A agreements, but none, to the best of our knowledge, in debt finance.

Thus, the potential of MAC clauses in debt finance is not fully utilised, due to the unique characteristics of debt finance (market reputation, risk diversification techniques, domino effect as a result of cross-default, etc). This significantly undermines the role and efficiency of MAC clauses in debt finance, as lenders rely on other contractual protection mechanisms to offset the risks more efficiently. However, it would be oversimplistic to conclude that because of this MAC clauses in debt finance are inefficient. Rather, their role in debt finance should be more important for the renegotiation of debt finance and less so for termination. Based on the litigation of MAC in COVID-19-related M&A deals, it seems that the same trend is developing for MAC in M&A, where the threat of termination in reliance on a MAC clause is used to initiate conversation between the parties and to reduce the acquisition price.Footnote 103

Whether tactical renegotiation on the account of MAC should be allowed is a separate question. From an efficiency point of view, based on transaction costs and the inherent incompleteness of contracts, the answer should be yes. Moreover, MAC clauses are also unique in that they are incorporated only in high-profile financing and M&A deals, typically involving sophisticated commercial parties who can calculate their risks and modify their contractual language accordingly. The threat of renegotiation and termination can also have a positive effect on the incentives of the parties.