INTRODUCTION

What can managers do to decrease employee deviance behavior that is detrimental to group functioning? We know from the previous literature that managers’ motivational leadership behaviors (e.g., charismatic leadership and ethical leadership) may induce positive exchanges with followers, thus reducing deviance (e.g., Brown & Treviño, Reference Brown and Treviño2006; Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes, & Salvador, Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009). We also know that disciplines and behavioral norms established by authorities can help to suppress potential deviant acts (Hollinger & Clark, Reference Hollinger and Clark1982; Marx, Reference Marx1981; Tittle & Rowe, Reference Tittle and Rowe1973). In the workplace, leaders serve as agents of organizations and have the power to influence employee behaviors (Yukl, Reference Yukl1989). We know little, however, about the specific leadership behaviors that help to reinforce discipline, thwart employee disobedience, and secure group solidary. Therefore, the primary purpose of this study is two-fold: (1) to identify the deterrence function of leaders in reducing employee deviance behavior; and (2) to examine the conditions under which the deterrence function takes place.

Specifically, we advance a new perspective of the leader's role in the workplace by proposing a deterrence function of authoritarian leadership, defined as leadership behaviors that assert absolute authority and control over subordinates and demand unquestionable obedience from them (Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang, & Farh, Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004: 81). We choose to focus on authoritarian leadership because the key feature of this leadership style is to secure employee conformity through reinforcing discipline and signaling punishment of disobedience (Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000). Drawing from deterrence theory (Lawler, Reference Lawler and Lawler1986; Morgan, Reference Morgan1983), which states that the threat of retaliation from high-power actors can prevent low-power actors from performing deviant acts, we suggest that authoritarian leadership may be an effective leadership style in deterring employee deviance.

Deterrence takes the strongest effect when: (1) there is no ambiguity of the possible sanctions from the actors, and (2) the targets have much to lose if being sanctioned (Hollinger & Clark, Reference Hollinger and Clark1983; Lawler, Reference Lawler and Lawler1986; Waldo & Chiricos, Reference Waldo and Chiricos1972). We therefore propose two moderators of the deterrence effect of authoritarian leadership. First, past studies have shown that an authoritarian leader is more likely to threaten employees if the same leader simultaneously exhibits low benevolence (Chan, Huang, Snape, & Lam, Reference Chan, Huang, Snape and Lam2013). Following this logic, we propose that the negative effect of authoritarian leadership on deviance is stronger when the leader unambiguously signals his/her deterrence power by exhibiting low, rather than high benevolence. Second, resource dependence theory (Salancik & Pfeffer, Reference Salancik and Pfeffer1980) has long suggested that when employees are highly dependent on their leaders to obtain important work resources (e.g., work information, training opportunities, and social support), the cost of disobeying the leader is prohibitive (Emerson, Reference Emerson1962; Molm, Reference Molm1989). Thus, we expect that the deterrence effect of authoritarian leadership is likely to be maximized when employees are more, rather than less resource dependent on their leaders.

This research makes three main contributions to the literature. First, we provide empirical evidence of the functionality of authoritarian leadership of deterring deviance behavior. By demonstrating the social function of authoritarian leadership, we provide empirical evidence to explain the phenomenon of the prevalence of this leadership style in organizations (De Hoogh, Greer, & Den Hartog, Reference De Hoogh, Greer and Den Hartog2015; Huang, Xu, Chiu, Lam, & Farh, Reference Huang, Xu, Chiu, Lam and Farh2015; Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2008). Second, we contribute to the deviance literature by theorizing specific sets of leadership behavior that can help to deter employee deviance. Third, by including the moderators of resource dependence and leader benevolence, we extend deterrence theory by showing the two key conditions for a deterrence effect to take place. Integrating resource dependence theory and deterrence theory also allows us to answer the call from Chen, Eberly, Chiang, Farh, and Cheng (Reference Chen, Eberly, Chiang, Farh and Cheng2014) to examine the conditions under which authoritarian leadership may be functional in the workplace.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

Deterrence Theory

Deterrence theory proposes that the threat of retaliation from one high-power actor can prevent another lower-power actor from initiating or stopping some course of action (Lawler, Reference Lawler and Lawler1986; Morgan, Reference Morgan1983). The key notion of deterrence theory is that human behaviors are rational to the extent that some deviant acts can be deterred by negative incentives inherent in sanctions (Wenzel, Reference Wenzel2004). The deterrence theory is highly influential in social sciences, because it provides the intellectual foundation for law enforcement, crime deterrence, and information security policies (Achen & Snidal, Reference Achen and Snidal1989; Delpech, Reference Delpech2012; Geerken & Gove, Reference Geerken and Gove1975; Nagin & Pepper, Reference Nagin and Pepper2012). Classic deterrence theory focuses on dynamics of formal sanctions and proposes that the higher costs of sanctions for a deviant act, the more individuals are deterred from that act (Gibbs, Reference Gibbs1975). More contemporary research extends the classic theory by including informal sanctions such as social-disapproval (e.g., socially-imposed embarrassment), and argues that both formal and informal sanctions can influence individuals’ decisions about engaging in deviant acts (Grasmick & Kobayashi, Reference Grasmick and Kobayashi2002; Pratt, Cullen, Blevins, Daigle, & Madensen, Reference Pratt, Cullen, Blevins, Daigle, Madensen, Cullen, Wright and Blevins2006). This proposition has been supported by group research in a management context. For example, the threat of formal group sanctions, has been found to reduce corporate fraud (Yiu, Xu, & Wan, Reference Yiu, Xu and Wan2014) and improve ethical decision making (Rottig, Koufteros, & Umphress, Reference Rottig, Koufteros and Umphress2011). Also, using a sample of Chinese respondents in a telecommunications company, Xu, Huang, and Robinson (Reference Xu, Huang and Robinson2017) demonstrated that experienced ostracism from other group members tends to deter the focal employees from free-riding and drive them to exhibit more helping behavior, especially for those employees who strongly identify with their group and have a longer tenure.

A deterrence perspective also suggests that leaders’ actions are required to deter group members from committing deviant behaviors (Raven, Reference Raven2008; Tepper et al., Reference Tepper, Carr, Breaux, Geider, Hu and Hua2009; Tyler, Reference Tyler2004; Warren, Reference Warren1968). For instance, Tyler (Reference Tyler2004) has suggested that it is a necessary element of leadership to control employee detrimental behavior. However, the empirical evidence to support this assumption is limited.

Workplace Deviance

Workplace deviance refers to intentional behavior that violates organizational norms and is harmful to organizations and its members (Robinson & Bennett, Reference Robinson, Bennett, Sheppard and Bies1997). Much of the deviance research has investigated what factors motivate deviance (see a review by Bennett & Robinson, Reference Bennett, Robinson and Greenberg2003). Research has found factors such as injustice (Long & Christian, Reference Long and Christian2015; Michel & Hargis, Reference Michel and Hargis2017), psychological contract breach (Bordia, Restubog, & Tang, Reference Bordia, Restubog and Tang2008; Chiu & Peng, Reference Chiu and Peng2008), and workplace incivility (Andersson & Pearson, Reference Andersson and Pearson1999; Penney & Spector, Reference Penney and Spector2005) relate to higher levels of deviance behavior. Workplace deviance has been found to have high costs for both individuals and organizations (e.g., Detert, Treviño, Burris, & Andiappan, Reference Detert, Treviño, Burris and Andiappan2007; Needleman, Reference Needleman2008).

Bennett and Robinson (Reference Bennett and Robinson2000) have identified two types of workplace deviance: interpersonal deviance (i.e., being rude, playing mean pranks, and making fun of others), and organizational deviance (i.e., theft, absenteeism, and tardiness). These two types of deviance are related, but distinct constructs, which tend to be influenced by different factors (Giacalone & Greenberg, Reference Giacalone and Greenberg1997). Specifically, interpersonal-oriented factors better predict interpersonal deviance, while organizational-oriented factors better predict organizational deviance (Berry, Ones, & Sackett, Reference Berry, Ones and Sackett2007; Ilies, Nahrgang, & Morgeson, Reference Ilies, Nahrgang and Morgeson2007). Moreover, organizational deviance can be largely preceded by organizational punitive procedures (Manrique de Lara, Reference Manrique de Lara2006). Interpersonal deviance is more closely related to interpersonal dynamics among members, which are more likely to be affected by group leaders. For these reasons in this article, we focus on interpersonal deviance as opposed to organizational deviance.

Leadership has been identified as a key factor to influence employee deviance (Lian, Ferris, & Brown, Reference Lian, Ferris and Brown2012; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Mo & Shi, Reference Mo and Shi2017). Scholars have found that motivational forms of leadership are related to employees exhibiting lower levels of deviant behavior (authentic leadership: Erkutlu & Chafra, Reference Erkutlu and Chafra2013; ethical leadership: Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009). One often-invoked explanation of this effect of motivational leadership has been grounded in social exchange theory (Erkutlu & Chafra, Reference Erkutlu and Chafra2013; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009). The core argument is that if a leader treats employees well, followers tend to reciprocate by suppressing deviant acts that may harm the work group or the organization.

In addition to building positive social exchanges with followers, theory and research suggests that leaders may directly suppress deviant acts by employees through the use of sanctions and reinforcement of discipline (Litzky, Eddleston, & Kidder, Reference Litzky, Eddleston and Kidder2006; Neubert, Kacmar, Carlson, Chonko, & Roberts, Reference Neubert, Kacmar, Carlson, Chonko and Roberts2008). Surprisingly, we know very little about the leadership role in suppressing employee deviance. To advance our understanding of this leadership role, we draw upon deterrence theory to propose a functional utility of leader behavior (e.g., authoritarian leadership) in reducing employee workplace deviance and identify possible boundary conditions.

The Deterrence Effect of Authoritarian Leadership

Authoritarian leaders require their followers to obey their instructions completely, reinforce group norms through imposing strict discipline, and exercise sanctions on subordinates who fail to follow rules (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004). An authoritarian leadership style has been widely observed in various contexts, such as policing (Sandler & Mintz, Reference Sandler and Mintz1974; Wilson, Reference Wilson1978), the military (Geddes, Frantz, & Wright, Reference Geddes, Frantz and Wright2014), sport (Kellett, Reference Kellett2002) and organizations in Western and Eastern countries (Aycan, Reference Aycan, Yang, Hwang and Kim2006; De Hoogh et al., Reference De Hoogh, Greer and Den Hartog2015; Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000; Martinez, Reference Martinez, Elvira and Davila2003).

We propose that authoritarian leadership is likely to deter employee deviance behavior. This is because, according to deterrence theory, effective deterrence occurs when leaders have the power to drive employees to comply with group norms (Tyler, Reference Tyler2004). Authoritarian leaders signal to followers that disobedience is associated with potential sanction and therefore secure followers’ compliance to norms (Carmichael & Piquero, Reference Carmichael and Piquero2004; Grasmick & Bursik Jr., Reference Grasmick and Bursik1990; Williams & Hawkins, Reference Williams and Hawkins1986). Indeed, when theorizing the effects of authoritarian leadership, Farh and Cheng (Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000) explicitly argued that authoritarian leaders tend to ensure their subordinates’ behavioral compliance with group norms through threatening punishment for disobedience. Following this logic, we argue that authoritarian leadership has a deterrence effect and will suppress employee deviance behavior.

It is worth mentioning that authoritarian leadership may share some common features (i.e., initiating punishment) with other destructive leadership styles, such as abusive supervision (Tepper, Reference Tepper2000) and supervisory undermining (Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, Reference Duffy, Ganster and Pagon2002). However, authoritarian leaders devalue and humiliate followers to a lesser degree than leaders who engage in abusive supervision and supervisory undermining. For instance, an abusive supervisor may humiliate a follower and put this employee down in front of others (Tepper, Reference Tepper2000). Supervisory undermining includes behaviors such as belittling followers’ ideas and insulting them (Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Ganster and Pagon2002). Authoritarian leaders, in contrast, rather than degrading followers seek to safeguard order and discipline through utilizing their hierarchical power (De Hoogh et al., Reference De Hoogh, Greer and Den Hartog2015; Hwang, Reference Hwang, Chen and Lee2008). In this sense, authoritarian leaders who reinforce group hierarchy and threaten disobedience are inclined to focus on setting up group norms and achieving better group performance (Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000). Indeed, authoritarian leadership has been found to increase group functionality. For example, a study of service companies in Netherlands showed that authoritarian leaders motivate increased team performance through creating a psychologically safe environment (De Hoogh et al., Reference De Hoogh, Greer and Den Hartog2015). In a study of Chinese telecommunications companies, authoritarian leadership was found to outperform transformational leadership in increasing firm performance in harsh economic environments (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Xu, Chiu, Lam and Farh2015). In sum, we propose:

Hypothesis 1: Authoritarian leadership will be negatively related to interpersonal deviance.

Moderating Roles of Leader Benevolence and Employee Resource Dependence

There may be instances in which authoritarian leaders may be perceived as less of a deterrent, and consequently will be less effective in inhibiting employee deviance. Research on deterrence theory suggests that two key conditions determine the extent to which an effective deterrence effect can be maximized (D'arcy & Herath, Reference D'arcy and Herath2011; Grasmick & Kobayashi, Reference Grasmick and Kobayashi2002; Hollinger & Clark, Reference Hollinger and Clark1983). First, the perceived certainty of sanctions should be made clear. The high-power actor needs to send clear signals about the consequences of disobedience. Second, the perceived severity of sanctions should be made clear, in that punishment will inflict substantial losses for the low-power actor. As noted by Ehrlich (Reference Ehrlich1975), the deterrence process is best viewed as a combination of certainty and severity of sanctions. For example, increasing the certainty of punishment is less likely to deter deviant acts when the severity of sanctions is low. And vice versa, a high severity of punishment is less likely to act as a deterrence when the probability of receiving sanctions is low (Grasmick & Kobayashi, Reference Grasmick and Kobayashi2002). Extending this logic to the context of authoritarian leadership, we propose that the optimal deterrence effect of authoritarian leadership will be the strongest when the two conditions are both met: first, under conditions of low leader benevolence which sends a strong deterrence signal to employees, in that it is more certain that the leader will initiate sanctions, and second, when the employee has high resource dependence on the leader and is exposed to suffering severe losses.

Specifically, in terms of leader benevolence, past research has suggested that authoritarian leadership can be coupled with both high and low levels of leader benevolence (De Hoogh et al., Reference De Hoogh, Greer and Den Hartog2015; see paternalistic leadership as a pattern of high on both, Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2008). Leader benevolence refers to leaders’ individualized and holistic concern about employees’ personal and familial well-being (Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000). Researchers have found that authoritarian leaders may sometimes exhibit benevolence to their subordinates, which tends to mitigate the negative effects of authoritarian leadership on employee job satisfaction (Farh, Cheng, Chou, & Chu, Reference Farh, Cheng, Chou, Chu, Tsui, Bian and Cheng2006), organizational-based self-esteem, job performance, and organizational citizenship behavior (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Huang, Snape and Lam2013).

We suggest that, from a deterrence perspective, when a leader exhibits high authoritarianism and low benevolence, such behavior conveys a clear signal to employees that not conforming to the leader's orders will not be forgiven and will invoke sanctions. As a result, employees are less likely to exhibit behaviors that violate the behavioral norms imposed by the leader. Leader benevolence has been found to buffer the negative effects of authoritarian leadership on employee positive work outcomes (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Huang, Snape and Lam2013). As such, an authoritarian leader who is also seen as high in benevolence may send mixed messages to employees about the consequences of deviant behaviors in that they may feel that these negative behaviors might be forgiven or the leader will be less likely to impose harsh sanctions on them. As a result, we argue that low benevolence serves as an important condition to trigger the deterrence effect of authoritarian leadership.

Second, resource dependence theory has been utilized to explain the relationship between leaders and employees (see a review by Hillman, Withers, & Collins, Reference Hillman, Withers and Collins2009). When leaders have the power to allocate important resources to followers, they have the power to influence their behavior (Chou, Cheng, & Jen, Reference Chou, Cheng and Jen2005). We propose that when an employee has high resource dependence on their leader, punishment from the leader will potentially incur a greater level of loss of work resources for the employee. Under this condition, authoritarian leadership is more effective in deterring deviance, as the cost of disobedience by the employee is prohibitive. In contrast, an employee with a lower level of resource dependence is less likely to be deterred by an authoritarian leader, because the potential for a loss of resources is low.

In sum, we propose that authoritarian leadership will have the strongest instrumental function in deterring employees from deviance behavior when the leader exhibits a low level of benevolence, and when employee is highly dependent on the leader to obtain important work resources. Taken together, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 2: Benevolent leadership and resource dependence will jointly moderate the link between authoritarian leadership and interpersonal deviance, such that the negative relationship between authoritarian leadership and interpersonal deviance is the strongest when leader benevolence is low and employee resource dependence is high.

METHODS

We tested the proposed hypotheses in two independent samples. In Study 1, we collected data from a Chinese state-owned enterprise and used an indigenous Chinese measure for employee interpersonal deviance behavior developed by Farh, Earley, and Lin (Reference Farh, Earley and Lin1997). To examine whether our model can be generalized to broader deviance behaviors, Study 2 was designed to replicate the findings in Study 1, but used a well-established measure of workplace interpersonal deviance (Bennett & Robinson, Reference Bennett and Robinson2000). To increase the generalizability of our findings, we conducted Study 2 in a different setting of a private insurance company in China.

STUDY 1

Sample and Procedures

We conducted Study 1 in a state-owned power station in a southeastern city of China. Respondents were front-line employees and their immediate supervisor. Their job responsibilities include mechanical engineering, chemical engineering, operational maintenance, and so on. Pencil and paper surveys were distributed and collected during working hours by the first author and two research assistants from the HR department. At Time 1, employees were invited to respond to a survey assessing their supervisor's authoritarian and benevolent leadership and their own levels of resource dependence on their supervisor. We also collected demographic variables at Time 1. Each employee received a cover letter explaining the purpose of the study, a survey, and a self-sealing envelope. To assure confidentiality, respondents had the option of handing their completed sealed survey directly to the research assistants on site or returning their sealed surveys to a central location in the power station. At Time 2 (three weeks later), employees were asked to rate the quality of their relationship with their leader, and supervisors were asked to evaluate each follower's interpersonal deviance behavior. To match followers’ responses with supervisors’ evaluations, each survey was coded with a research-assigned identification number.

We invited 450 employees to participate in this study. We finally received 320 follower responses reporting to 40 immediate supervisors, with a response rate of 71.1%. The average number of employees per supervisor was 8. In the follower sample, 73.4% were male, 73.8% received a high-school education, and 84.5% were married or living as married. The average age and tenure with supervisors were 40.2 and 4.4 years, respectively.

Measures

All of the scales used in Study 1 were available in Chinese. For convenience, the English versions of the scales used are shown in the Appendix I. All items used a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree.

Authoritarian leadership

Authoritarian leadership was measured using a 9-item scale developed by Cheng et al. (Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004). Sample items are ‘my immediate supervisor asks me to obey his/her instructions completely’, ‘my supervisor determines all decisions in the team whether they are important or not’, and ‘my supervisor always has the last say in meetings’. The Cronbach's alpha in this sample was 0.86.

Benevolent leadership

Benevolent leadership was measured using an 11-item scale developed by Cheng et al. (Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004). Sample items are ‘my supervisor takes very thoughtful care of subordinates who have spent a long time with him/her’, ‘my supervisor devotes all his/her energy to taking care of me’, and ‘beyond work relations, my supervisor expresses concern about my daily life’. The Cronbach's alpha was 0.96.

Resource dependence

We used Farh et al.’s (Reference Farh, Cheng, Chou, Chu, Tsui, Bian and Cheng2006) six-item scale to measure resource dependence. Sample items are ‘whether I can get necessary working resources depends on my supervisor's decisions’, ‘my promotion largely depends on my supervisor’, and ‘I need my supervisor's support to finish my work’. The Cronbach's alpha was 0.95.

Interpersonal deviance

Interpersonal deviance was measured using a 3-item scale adapted by Hui, Law, and Chen (Reference Hui, Law and Chen1999) from a scale originally developed by Farh et al. (Reference Farh, Earley and Lin1997). The original scale consisted of four items to measure indigenous Chinese OCB of interpersonal harmony in a Taiwanese sample. Hui et al. (Reference Hui, Law and Chen1999) simplified and revalidated the scale by deleting one item that was judged to be inappropriate for employees working in Mainland China. While Farh et al. (Reference Farh, Earley and Lin1997) suggested that the scale represented maintaining interpersonal harmony, it more recently has been argued that this measure does not reflect the original intended definition of interpersonal harmony, but instead measures interpersonal deviance (Zhao, Wu, Sun, & Chen, Reference Zhao, Wu, Sun and Chen2012). The items were ‘often speaks ill of the supervisor or colleagues behind their backs’, ‘uses illicit tactics to seek personal influence and gain with harmful effect on interpersonal harmony in the company’, and ‘takes credit, avoids blame, and fights fiercely for personal gain’. The Cronbach's alpha was 0.96.

Control variables

As past research has suggested that demographic variables may influence employee work performance (Van Knippenberg, Van Knippenberg, De Cremer, & Hogg, Reference Van Knippenberg, Van Knippenberg, De Cremer and Hogg2005; Vandenberghe et al., Reference Vandenberghe, Bentein, Michon, Chebat, Tremblay and Fils2007) and deviance (Aquino & Douglas, Reference Aquino and Douglas2003), we controlled for employee gender, age, and tenure with supervisor. In addition, we followed other researchers (Stouten, van Dijke, Mayer, De Cremer, & Euwema, Reference Stouten, van Dijke, Mayer, De Cremer and Euwema2013; Tims, Bakker, & Xanthopoulou, Reference Tims, Bakker and Xanthopoulou2011) and controlled for employee educational level and marital status, because these variables have been suggested to influence employee reactions toward leadership behaviors. Further, since authoritarian leadership and benevolent leadership have been theorized as two dimensions of the paternalistic leadership construct (Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000), we also controlled for the third dimension of moral leadership in the analysis.

Finally, we suggest that a social exchange perspective offers an alternative explanation for the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee deviance. The social exchange perspective posits that followers may tend to reciprocate to negative exchanges with their leader through increasing their deviant behaviors (see Xu, Huang, Lam, & Miao, Reference Xu, Huang, Lam and Miao2012 for an example of abusive supervision). Because authoritarian leaders disregard employees’ suggestions and discount their contribution (Aryee, Chen, Sun, & Debrah, Reference Aryee, Chen, Sun and Debrah2007), one would expect that authoritarian leaders will have negative exchanges with employees who will therefore engage in higher levels of deviance behavior. Therefore, to take a social-exchange perspective into account we controlled for leader-member exchange (LMX) in our model. We measured LMX using the LMX-12 scale (Liden & Maslyn, Reference Liden and Maslyn1998) at Time 2. Sample items are ‘I like my supervisor very much’, ‘My supervisor would defend me to others in the organization if I made an honest mistake’, ‘I admire my supervisor's professional skills’, and ‘I do not mind working my hardest for my supervisor’. The Cronbach's alpha was 0.93.

Statistical Analytical Methods

Given that employees were nested within groups (reporting to the same supervisor), we considered the possibility of data homogeneity due to the same supervisor’ assessment of employee deviance. We calculated Intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC1) for dependent variables to examine whether there were supervisor effects on the nested data. ICC values were high (> 0.10: Bliese, Reference Bliese, Klein and Kozlowski2000) for interpersonal deviance (ICC1 = 0.57), indicating a significant portion of the variance generated by the same-supervisor effect in the outcome variable. We therefore followed the recommendation of Janssen, Lam, and Huang (Reference Janssen, Lam and Huang2010) and employed linear mixed modeling to decompose the total observed variance into individual- and group-level variances. As the hypothesized model (Figure 1) only focuses on individual-level relationships, we controlled for possible group-level variance in the analyses. Before creating the interaction term, following the recommendations of Aiken and West (Reference Aiken and West1991), the independent variable and the moderators were grand mean-centered.

Figure 1. Conceptual model

RESULTS

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Before testing the hypotheses, using Mplus 8 we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) to examine the validity of our measurement model. According to Kline (Reference Kline2015), estimation methods for continuous model variables are not the best choice when the indicators are Likert-scale items. Kline suggested several ways to deal with this issue including item parceling. In this study, we followed Kline's suggestion and formed three parcels for both authoritarian leadership and benevolent leadership. Each parcel was formed from three to four randomly assigned items. As Shown in Table 1, the four-factor model (authoritarian leadership, benevolent leadership, resource dependence, and interpersonal deviance) showed an acceptable fit to the data (χ2 (84) = 302.39, root mean square of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.08, comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.95, Tucker–Lewis Index [TLI] = 0.93, standardized root mean square residual [SRMR] = 0.05), and all indicators loaded significantly on the intended factor (p < 0.001). This result supports the distinctiveness of the constructs used in this study.

Table 1. Study 1: Fit comparisons of alternative factor models

Notes: Model A: 3-factor model combining authoritarian leadership and benevolent leadership; Model B: 3-factor model combining authoritarian leadership and resource dependence; Model C: 2-factor model combining authoritarian leadership, benevolent leadership, and resource dependence as a factor; and Model D: 1-factor model combining all variables. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Descriptive Statistics

Means, standard deviations, and the correlations among variables are shown in Table 2. Authoritarian leadership was positively related to benevolent leadership (r = 0.13, p < 0.05) and resource dependence (r = 0.42, p < 0.01). Authoritarian leadership was positive related to interpersonal deviance (r = 0.19, p < 0.01).

Table 2. Study 1: Variable, means, standard deviations, and correlations

Notes: Tenure and age were coded in years. Gender was coded as 0 = male, 1 = female. Education was coded as 0 = below high school, 1 = above high school. Marital status was coded as 0 = single, 1 = married or living as married, 2 = separated/divorced/widowed. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

Hypotheses Testing

Hypotheses 1 predicted a negative relationship between authoritarian leadership and interpersonal deviance. As shown in Table 3, we entered control variables in Model 1. We then regressed authoritarian leadership, benevolent leadership, and resource dependence on interpersonal deviance in Model 2. We found authoritarian leadership was not significantly related to interpersonal deviance (b = 0.08, p > 0.05). Therefore, Hypotheses 1 was not supported. In Model 3, we regressed all two-way interactions on interpersonal deviance and found none of them to be significant.

Table 3. Hierarchical multilevel analyses for the hypothesized three-way interaction in Study 1

Notes: Unstandardized regression coefficients are shown. *p < 0.05;**p < 0.01.

To test the proposed three-way interaction we entered the three-way interaction term of authoritarianism, benevolence, and resource dependence in the regression in Model 4. In this model the three-way interaction term was found to be positively related to interpersonal deviance (b = 0.23, p < 0.01).

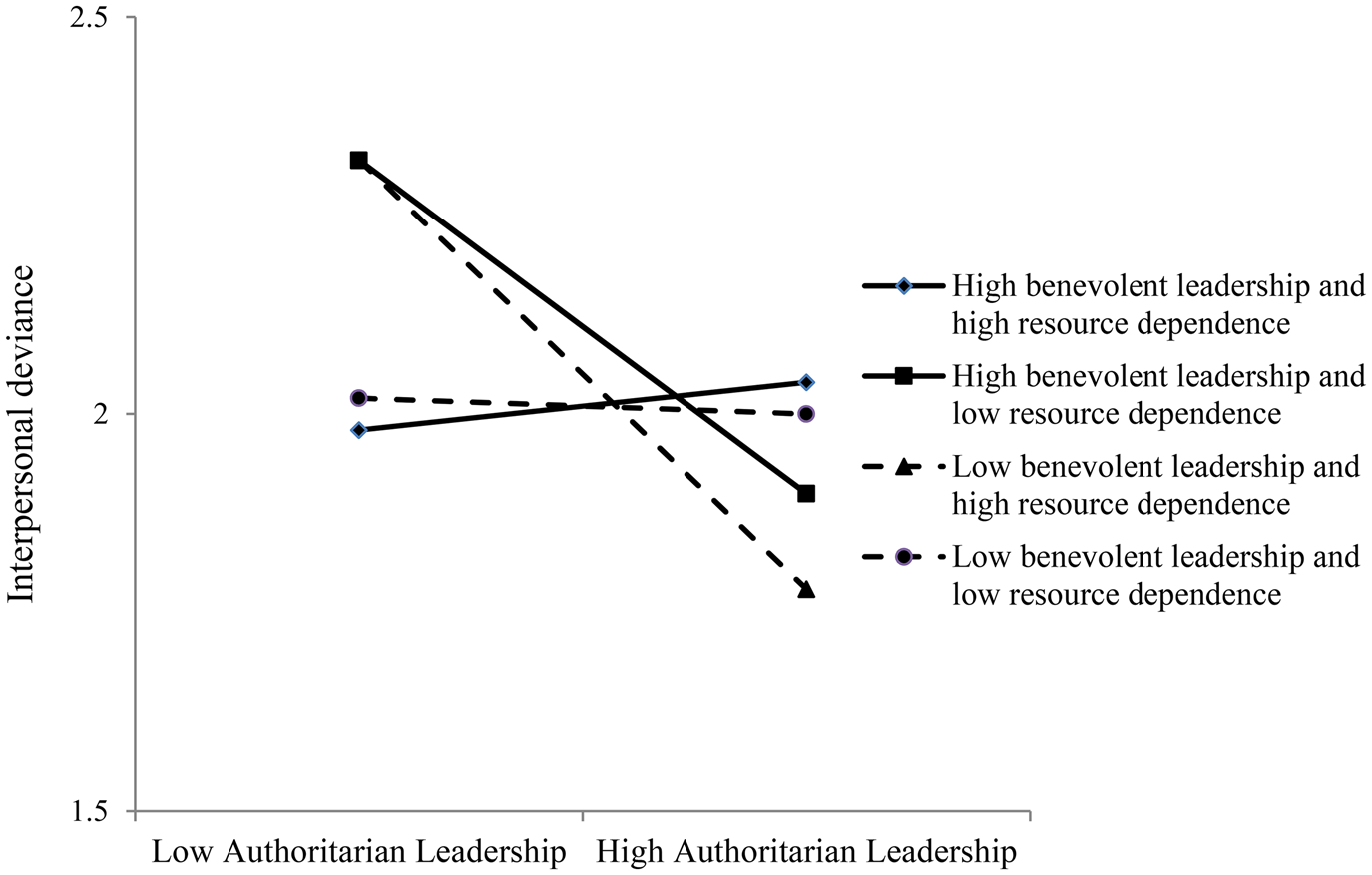

To assist with interpretation, we followed the procedures outlined by Aiken and West (Reference Aiken and West1991) to plot the three-way interaction (see Figure 2). Consistent with our expectation, simple slope tests showed that authoritarian leadership reduced interpersonal deviance only when benevolence is low and resource dependence is high (simple slope = −0.38, p < 0.05). Furthermore, the relationship between authoritarian leadership and interpersonal deviance is not significant when benevolence is high and resource dependence is low (simple slope = 0.04, n.s), and when benevolence is high and dependence is high (simple slope = 0.10, n.s.). But, we found a positive relationship when benevolence is low and resource dependence is low (simple slope = 0.48, p < 0.05). We also performed a simple slope difference test to examine whether differences between pairs of slopes were significantly different from zero (Dawson & Richter, Reference Dawson and Richter2006). The analysis confirmed that the slope for low benevolence and high resource dependence is more negative than for high leader benevolence and high resource dependence (t = −2.45, p < 0.05). This is also the case for when leader benevolence is high and resource dependence is low (t = −1.91, p = 0.06), and when leader benevolence is low and resource dependence is low (t = −3.25, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 2 thus was supported.

Figure 2. The relationship between authoritarian leadership and interpersonal deviance under conditions of low and high benevolence leadership and resouce dependence in Study 1

STUDY 2

Sample and Procedures

The primary goal of Study 2 was to replicate the pattern of the deterrence effect shown in Study 1, but using a universal measurement of interpersonal deviance. We collected the data for Study 2 from an insurance company in a northeastern city in China. We followed the same procedure as in Study 1. At Time 1, followers were invited to rate their supervisors’ authoritarian and benevolent leadership, and their own resource dependence levels. At Time 2 (two weeks later), followers were asked to rate their LMX, and supervisors were asked to evaluate their followers’ interpersonal deviance.

We distributed paper-and-pencil surveys to 360 employees and their immediate supervisors. The final sample consisted of 262 employees reporting to 53 supervisors, representing a response rate of 72.7%. The average number of followers per supervisor was 5. In the follower sample, 30% were males, and 32.8% received a high-school education. The average age and tenure with supervisor were 39.60 and 3.10 years.

Measures

Authoritarian leadership, benevolent leadership, and resource dependence

We measured these three scales using the same measurements as those we used in Study 1. Considering the survey space and feedback from the insurance company on the lack of applicability of specific items, we excluded several scale items. For the benevolent leadership scale, we excluded one item: ‘my supervisor is like a family member when he/she gets along with us’. For the resource dependence scale, we excluded two items: ‘my pay increase is largely influenced by my supervisor’ and ‘the welfare I can get depends on my supervisor's decisions’. The Cronbach's alphas were 0.83 for authoritarian leadership, 0.91 for benevolent leadership, and 0.69 for resource dependence.

Interpersonal deviance

We adapted items from Bennett and Robinson's (Reference Bennett and Robinson2000) measure that included 5 interpersonal deviance items.[Footnote 1] This measure used a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The Cronbach's alphas was 0.94. The items are shown in Appendix II.

Controls

We controlled for employees’ gender, age, tenure with supervisor, and education level. We also controlled for LMX in our model. LMX was measured by the LMX-7 scale (Graen & Uhl-Bien, Reference Graen and Uhl-Bien1995). Sample items were ‘my supervisor recognizes my potential’, ‘I have an effective working relationship with my supervisor’, and ‘I usually know where I stand with my manager’. The Cronbach's alpha of this scale was 0.84.

RESULTS

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

As shown in Table 4, similar to Study 1, using item parceling (three parcels for both authoritarian leadership and benevolent leadership), the hypothesized four-factor model was found to fit the data very well (χ2 (84) = 220.64, RMSEA = 0.08, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.91, SRMR = 0.06). This four-factor model also produced a superior fit than the alternative models examined.

Table 4. Study 2: Fit comparisons of alternative factor models

Notes: Model A: 3-factor model combining authoritarian leadership and benevolent leadership; Model B: 3-factor model combining authoritarian leadership and resource dependence; Model C: 2-factor model combining authoritarian leadership, benevolent leadership, and resource dependence as a factor and two behavioral deviance dimensions as a factor; and Model D: 1-factor model combining all variables. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

Descriptive Statistics

Table 5 shows the descriptive statistics and inter-correlations among the study variables.

Table 5. Study 2: Variable, means, standard deviations, and correlations

Notes: Tenure and age were coded in years. Gender was coded as 0 = male, 1 = female. Education was coded as 0 = below high school, 1 = above high school.

*p < .05; **p < .01

Hypotheses Testing

The ICC1 values of interpersonal deviance (ICC1 = 0.74) was high, and therefore, as in Study 1, we used linear mixed modeling to test our hypotheses.

Table 6 presents the results of the regression analyses. We again entered the control variables in Model 1. We then entered authoritarian leadership, benevolent leadership, and resource dependence in Model 2 and we found that authoritarian leadership was not significantly related to interpersonal deviance (b = −0.09, p > 0.05). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was not supported. In Model 3, we entered all two-way interactions and none of these were significant. In Model 4, the three-way interaction was significantly related to interpersonal deviance (b = 0.13, p < 0.01).

Table 6. Hierarchical multilevel analyses for the hypothesized three-way interaction in Study 2

Notes: Unstandardized regression coefficients are shown. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Next, we plotted the significant three-way interaction of authoritarian leadership, benevolent leadership, and resource dependence on interpersonal deviance. As shown in Figure 3, consistent with Study 1, the relationship between authoritarian leadership and interpersonal deviance was only negative when leader benevolence is low and resource dependence is high (simple slope = −0.32, p < 0.05). The authoritarian leadership – interpersonal deviance relationship was not significant when benevolence is high and dependence is high (simple slope = 0.02, n.s.), and when benevolence is low and dependence is low (simple slope = 0.00, n.s.), and when leader benevolence is high and resource dependence is low (simple slope = −0.19, n.s). The simple slope difference test supported that the slope under low benevolence and high resource dependence was significantly different from high leader benevolence and high resource dependence (t = −2.14, p < 0.05), and low leader benevolence and low resource dependence (t = −2.01, p < 0.05), but not different from the slope under high leader benevolence and low resource dependence (t = −0.70, p > 0.49). This result suggests that high leader benevolence and low resource dependence may form another possible situation for authoritarian leaders to decrease interpersonal deviance. This finding is consistent with the extant literature from a social exchange perspective. Detailed discussion will be provided in the next section. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was partially supported.

Figure 3. The relationship between authoritarian leadership and interpersonal deviance under conditions of low and high benevolence leadership and resouce dependence in Study 2

Post-Hoc Power Analyses

Following recommendations from Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, and Buchner (Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007), we calculated the statistical power of the proposed three-way interaction for two studies. We set the sample size at 320 for Study 1, and 262 for Study 2, and the alpha level at 0.05. The results showed a sufficient statistical power for both studies (Study 1 = 0.99, Study 2 = 0.91), which are above the acceptable level of 0.80.

DISCUSSION

In two independent studies from different industries with multi-sourced data collection designs, we found that authoritarian leadership has a deterrence effect in reducing employee interpersonal deviance under two conditions: low leader benevolence and high employee resource dependence. This finding not only supports Tyler's (Reference Tyler2004) assertion that a deterrence function can be an important outcome of leadership through its effects on limiting employee deviance, but also provides clear evidence of the two key conditions for a leader to initiate this deterrence effect.

Theoretical Implications

This study has several theoretical implications. Firstly, we contribute to the workplace deviance literature by linking it with deterrence theory. We theorized and demonstrated that leaders are able to deter employee workplace interpersonal deviance behavior. In addition to past research that has provided substantial knowledge of how positive leadership styles can decrease employee deviance through the social exchange process (Lian et al., Reference Lian, Ferris and Brown2012; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009), this study is the first study known to us, to theorize an impact of leadership on employee deviance from a deterrence perspective. Specifically, we demonstrate that an authoritarian leadership style, which emphasizes discipline and unquestioned obedience from employees, has a deterrent role that reduces employee interpersonal deviance. Further, by including LMX in our model, our study demonstrates the unique role of a deterrence process in explaining the functionality of authoritarian leadership on deviance.

Second, we contribute to the authoritarian leadership literature by demonstrating the deterrence function of authoritarian leadership and investigating boundary conditions. Authoritarian leadership has been of interest to social scientists for more than half a century (Bass & Bass, Reference Bass and Bass2008; De Hoogh & Den Hartog, Reference De Hoogh and Den Hartog2009; De Hoogh et al., Reference De Hoogh, Greer and Den Hartog2015; Lippitt, Reference Lippitt1940; Weber, Reference Weber1947). Most empirical studies of authoritarian leadership have shown its undesirable impacts on employee well-being and performance. The key assumption of the original authoritarian leadership theory made by Farh and Cheng (Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000), which proposed that authoritarian leaders enforce employee behavioral compliance through group norms has not been supported by sufficient research evidence. Our development of a deterrence perspective complements the existing literature and offers an insightful theoretical framework to illustrate the functionality of authoritarian leadership. Further research to explore other positive outcomes of authoritarian leadership or other types of controlling leaderships may prove useful.

Furthermore, we extend deterrence theory by investigating possible conditions of when the deterrence function of an authoritarian leader can be maximized. In general, deterrence theory proposes that perceived certainty and severity of sanctions are two essential conditions that compel people to regulate their deviant behaviors (Hollinger & Clark, Reference Hollinger and Clark1983; Waldo & Chiricos, Reference Waldo and Chiricos1972). This assumption received support in this research. In two independent studies, we found that authoritarian leadership poses a stronger deterrence effect on employee interpersonal deviance when the leader sends clear signals of punishments (i.e., low benevolence), and when the employee feels high vulnerability to punishment (i.e., when they are highly dependent on the leader for resources).

Another interesting discussion is that we did not find authoritarian leadership to be negatively related to interpersonal deviance (Hypothesis 1). It is possible that in addition to a deterrence perspective, other mechanisms may account for variance in interpersonal deviance due to authoritarian leadership. For example, Jiang, Chen, Sun, and Yang (Reference Jiang, Chen, Sun and Yang2017) found that authoritarian leadership has adverse impacts on employees’ psychological contract with their organization, which led to higher levels of employee organizational cynicism and deviant behaviors. Furthermore, research by Conway III and Schaller (Reference Conway and Schaller2005) also found that commands by an authority figure may lead to deviant behavior as individuals attribute the command to the social power of the authority figure, rather than to the real intention of the command. This attribution undermines the influence of the command, which then leads to individuals making deviant decisions. Thus, we do not discount the harmful effects of authoritarian leadership on employees; instead, our study adds to the existing literature by proposing a novel situation that authoritarian leadership can effectively suppress employee deviance. The implication of this finding needs to be interpreted with great caution. On one hand, authoritarian leadership can be functional especially under serious situations when obedience and group solidary matter most. From the other hand, it is important for leaders to be aware that an authoritarian style generally harms employees’ motivation towards discretionary effort (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Eberly, Chiang, Farh and Cheng2014; Schaubroeck, Shen, & Chong, Reference Schaubroeck, Shen and Chong2017; Zhang, Huai, & Xie, Reference Zhang, Huai and Xie2015).

In addition, though the proposed deterrence effect under low leader benevolence and high resource dependence was supported across two studies, the moderating pattern under the condition of low resource dependence was different. In Study 1, for low resource dependent employees we found a significant positive effect of authoritarian leadership on interpersonal deviance when the leader exhibited low leader benevolence to the employee (Figure 2). Although not expected, this positive relationship is consistent with both the deterrence perspective and a social exchange perspective. From a deterrence perspective, authoritarian leaders who exhibit low benevolence signal to employees the certainty of them receiving punishment if they engage in interpersonal deviance. Employees who have low levels of resource dependence on their leader are however less likely to be deterred from deviance behavior due to the low level of cost they may suffer. Under this situation, consistent with a social exchange perspective, employees may choose to retaliate due to their experience of receiving negative exchanges with the leader. Further, previous research has shown that in response to poor treatment from their leader, an employee may engage in deviant behavior targeted at different foci such as their leader, the organization, or their coworkers (Kluemper et al., Reference Kluemper, Mossholder, Ispas, Bing, Iliescu and Ilie2018; Mitchell & Ambrose, Reference Mitchell and Ambrose2007; Tepper, Henle, Lambert, Giacalone, & Duffy, Reference Tepper, Henle, Lambert, Giacalone and Duffy2008). A possible reason as to why the positive relationship between authoritarian leadership and interpersonal deviance under conditions of low benevolence and low resource dependence was not found in study 2 may be that employees can choose to retaliate against other targets rather than coworkers. Future studies are encouraged to include different forms of deviance behavior to further investigate in this issue. A social exchange perspective may also explain why in Study 2 we found a second situation where authoritarian leadership acts to decrease employee interpersonal deviance (when leader benevolence is high and resource dependence is low). That is, when employees are treated well and have low resource dependence, they will tend to reduce their interpersonal deviance behavior to achieve more positive exchanges with their leader.

The different context between the two studies (a state-owned organization in Study 1 versus a private company in Study 2) may explain the findings in the two studies for the two different moderation effects for the low resource dependence condition. State-owned organizations provide employees with high job security and distribute bonuses based more on group performance and promotion based on seniority than individual performance (Unger & Chan,Reference Unger and Chan2004). Under these conditions, employees are more likely to retaliate using a wide range of deviance behavior if they are resource independent and their leaders are less benevolent. In the private sector, organizations face fierce market pressure to improve profit and employees are more task-oriented and take greater personal responsibility for their performance (Khuntia & Suar, Reference Khuntia and Suar2004). When leader benevolence is high, employees will be more likely to be provided with constructive feedback which will help them to develop their skills. As private sector employees take more responsibility for their own performance and their job security and personal development is dependent on their skill level, this feedback is likely to be more appreciated in this context rather than that of Study 1. We speculate might be the reason why we found that for resource independent employees, the beneficial impact of high benevolence in helping authoritarian leadership reducing interpersonal deviance is stronger in Study 2. Further research is needed to explore these contextual issues.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

There are several limitations of this article. First, we used Chinese samples in both studies. This means that the generalizability of our findings to other cultures may be limited. Although we did not use a cross-cultural sample, we replicated the findings in two different industries and used a measure for deviance in the second study that has been used in a wide range of studies in different cultural contexts. We are encouraged by a recent study of authoritarian leadership in a Western context (De Hoogh et al., Reference De Hoogh, Greer and Den Hartog2015), which found a positive influence of authoritarian leadership on group performance. This suggests that the benefits of authoritarian leadership may not be unique to an Eastern context. We recommend future research to replicate the current findings in other cultural samples.

In addition, not everyone we invited to participate responded to our survey. This may raise concerns about self-election bias. The relatively high response rates (71.1% for Study 1 and 73.4% for Study 2) and the fact that the main deterrence hypothesis has been replicated across two studies provides a level of mitigation against this concern. Causality is another concern. In our data, only employee deviance was measured at Time 2, whereas all other main variables were measured at Time 1. Without cross-lagged data, our results cannot completely rule out concerns of causality. A reversed argument – a high level of employee deviance results in leaders applying an authoritarian leadership style, is also possible. This perspective is supported by the abusive supervision literature, where employee deviance has been found to predict high abusive supervision (Lian et al., Reference Lian, Brown, Ferris, Liang, Keeping and Morrison2014). In our case, we suspect that witnessing employee exhibiting deviance behavior may result in leaders becoming more authoritarian in style to reduce these negative behaviors. We encourage future studies to include cross-lagged data to investigate the direction of the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee deviance.

Further, we argue that benevolent leadership and resource dependence are two key conditions for the deterrence effect of an authoritarian style. Investigating the psychological mechanisms for the deterrence function of authoritarian leadership is a promising avenue for future research. For example, according to Cheng et al. (Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004), an authoritarian leadership style refers to fear-inspiring behaviors. It might be that authoritarian leadership results in high levels of fear of sanctions in employees, which then deters them from deviance behavior. In addition, it is possible that the deterrence effect of authoritarian leadership triggers a prevention focus in employees, increasing their felt need for security and safety and desire to fulfil their duties and obligations through responsible behavior (Higgins, Shah, & Friedman, Reference Higgins, Shah and Friedman1997) leading to lower levels of deviance behavior.

Finally, because the effect sizes of the deterrence effect are relatively low across the two studies, practical implications for managers are limited. We encourage future studies to continue to investigate the deterrence effect of authoritarian leadership on employee deviant behavior, and to provide more evidence about the functionality of authoritarian leadership for the deterrence of employee deviant behavior.

CONCLUSION

The role of leaders in decreasing workplace deviance has been studied for decades. The unanswered question as to whether leaders can deter employee deviance, however, indicates that this line of research needs further investigation. Our study adds new insights regarding the positive function of authoritarian leadership on reducing employee deviance under certain conditions. That is, we theorize that when the leader is low on benevolence and when followers have high resource dependence on the leader, authoritarian leadership is more likely to have a deterrent effect. By illustrating an important positive effect of authoritarian leadership, we hope to encourage future studies of the deterrent role of leaders and the impact on individuals, teams, and organizations.

APPENDIX I

English Version of Measures Used in Study 1 and Study 2

Authoritarian and Benevolent Leadership (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004).

Authoritarianism

1. My supervisor asks me to obey his/her instructions completely.

2. My supervisor determines all decisions in the team whether they are important or not.

3. My supervisor always has the last say in meetings.

4. My supervisor always behaves in a commanding fashion in front of employees.

5. I feel pressured when working with him/her.

6. My supervisor exercises strict discipline over subordinates.

7. My supervisor scolds us when we can't accomplish our tasks.

8. My supervisor emphasizes that our group must have the best performance of all the units in the organization.

9. We have to follow his/her rules to get things done. If not, he/she punishes us severely.

Benevolence

1. My supervisor is like a family member when he/she gets along with us.

2. My supervisor devotes all his/her energy to taking care of me.

3. Beyond work relations, my supervisor expresses concern about my daily life.

4. My supervisor ordinarily shows a kind concern for my comfort.

5. My supervisor will help me when I am in an emergency.

6. My supervisor takes very thoughtful care of subordinates who have spent a long time with him/her.

7. My supervisor meets my needs according to my personal requests.

8. My supervisor encourages me when I encounter arduous problems.

9. My supervisor takes good care of my family members as well.

10. My supervisor tries to understand what the cause is when I don't perform well.

11. My supervisor handles what is difficult to do or manage in everyday life for me.

Resource dependence (Farh et al., Reference Farh, Cheng, Chou, Chu, Tsui, Bian and Cheng2006).

1. My promotion largely depends on my supervisor.

2. My pay increases are largely influenced by my supervisor.

3. The welfare I can get depends on my supervisor's decisions.

4. Whether I can get the necessary work resources depends on my supervisor's decisions.

5. My work is distributed by my supervisor.

6. I need my supervisor's support to finish my work.

Chinese Interpersonal Deviance (Hui et al., Reference Hui, Law and Chen1999).

This employee…

1. Often speaks ill of the supervisor or colleagues behind their backs.

2. Uses illicit tactics to seek personal influence and gain with harmful effect on interpersonal harmony in the company.

3. Takes credit, avoids blame, and fights fiercely for personal gain.

Deviance Measures Adapted from Bennett and Robinson (Reference Bennett and Robinson2000) Used in Study 2

Interpersonal Deviance

This employee…

1. Said something hurtful to someone at work.

2. Cursed at someone at work.

3. Played a mean prank on someone at work.

4. Acted rudely toward someone at work.

5. Publicly embarrassed someone at work.