INTRODUCTION

Close interactions between Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) and local institutions in the host country are an inevitable part of doing international business. Some of these interactions are expected and thus taken into consideration during the planning of an international expansion. This is usually the case when dealing with formal institutions such as government authorities and regulating bodies. On the other hand, interactions with informal institutions, such as civil society and community stakeholders, are usually unanticipated and may come as a surprise negatively impacting the MNE's ability to achieve its desired goals.

The role of institutions in the process of internationalization has been well covered in earlier research (Dunning & Lundan, Reference Dunning and Lundan2008). This has been done within the context of mitigating the Liability of Foreignness (LOF), defined as MNE's additional costs vis-à-vis local firms arising from various factors such as unfamiliarity with the local environment and discriminatory attitudes of local stakeholders (Hymer, Reference Hymer1976; Zaheer, Reference Zaheer1995). The Uppsala model (Johanson & Vahne, Reference Johanson and Vahne1977) proposed that firms follow a specific pattern of internationalization, starting from low-risk options and gradually increasing foreign market commitments and risk. This model was initially grounded in the theory of the firm (Cyret & March, Reference Cyret and March1963; Penrose, Reference Penrose1966), which viewed markets as a set of transactions. In the revised Uppsala model, Johanson and Vahne (Reference Johanson and Vahne2009: 1411) argue that the modern world has evolved, and now markets should be redefined as ‘networks of relationships in which firms are linked to each other in various, complex, and […] invisible patterns’. Accordingly, they introduce the notion of Liability of Outsidership (LOO), representing the costs related to the lack of connectedness of MNEs to the appropriate networks. This study is motivated by the need to uncover the nuances associated with the LOO under various institutional contexts.

We contribute to this discussion in three ways. First, in line with network theory, we propose an intermediary position, an agent representing the interests of the ‘outsider’ in cases when becoming an ‘insider’ is impossible due to certain institutional limitations. Second, within the context of Iran, we identify a specific informal network of merchants (bazaaries) who could play the role of such an intermediary. Third, we offer a series of propositions related to this subject. Our paper has theoretical implications, especially in relation to the liability of outsidership, in addition to several practical implications.

As we will explain later in this paper, the bazaaries’ network relationships are wide and dense and cover all strands of society, including powerful politicians. Accessing such a network becomes a vital strategic choice similar to the guanxi system in China (Farashahi & Hafsi, Reference Farashahi and Hafsi2009; Sheng, Zhou, & Li, Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011). Therefore, studying bazaaries network is motivated by both its relevance and importance to international business, and the paucity of management research explaining their role. We contribute not only to research addressing the role of this network in Iran, but also towards understanding informal social networks in other contexts such as guanxi in China or yongo in Korea.

Our article proceeds as follows. First, we present an overview of the theoretical background underlying this research. We then describe the specificity of the locational context in this article and its importance for international business. Next, we investigate the case of the informal network of bazaaries in both political and economic life in Iran. The penultimate part of our article provides conceptual development grounded in the Iranian case by offering a series of propositions. We conclude the article with a discussion of the practical implications for MNEs and suggest avenues for future research.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Institutions and International Management Research

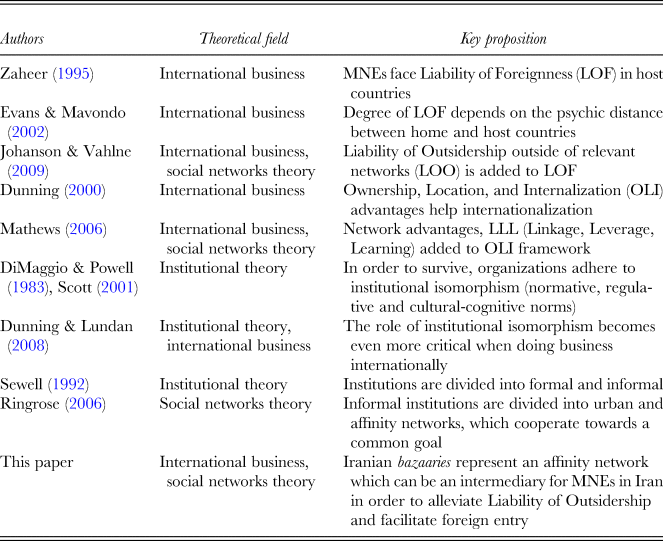

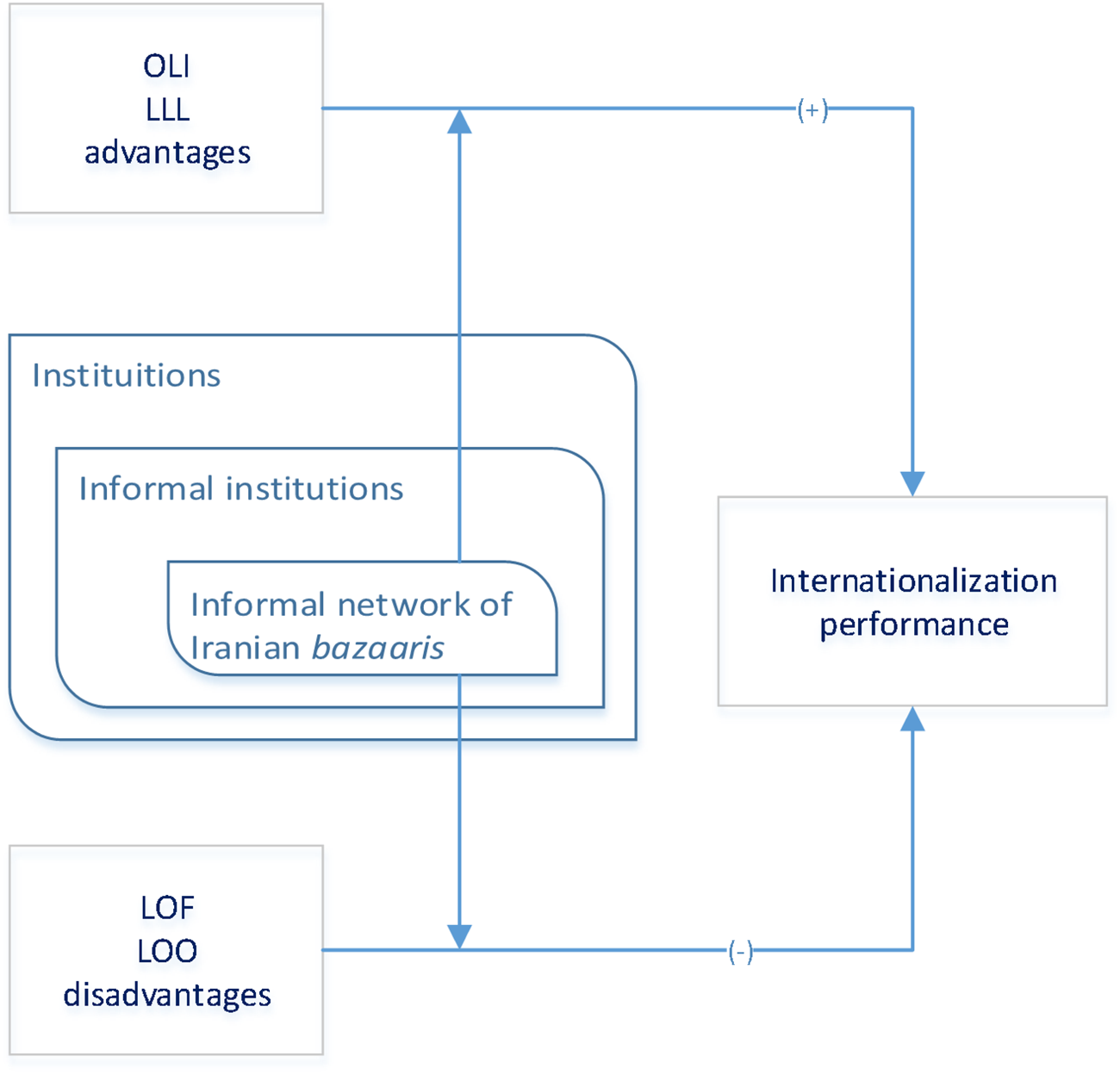

International management research deals with MNEs and exporting-importing firms, and problems encountered by them while pursuing their internationalization strategy (Ricks, Reference Ricks1991). In her review of international management research, Lu (Reference Lu2003) notes that the application of institutional theory to international business became quite popular in the 1990s (e.g., Davis, Desai, & Francis, Reference Davis, Desai and Francis2000; Khanna & Palepu, Reference Khanna and Paleku1997; Kostova & Zaheer, Reference Kostova and Zaheer1999). Dunning and Lundan (Reference Dunning and Lundan2008) have formally incorporated institutions in one of the main models of international management research, the OLI eclectic paradigm (Dunning, Reference Dunning2000). Table 1 and Figure 1 summarize the development of the related literature.

Table 1. Summary of Literature

Figure 1. Theoretical summary

Institutions refer to formal rules (e.g., constitutions, laws, and regulations) and informal constraints (e.g., norms of behavior, self-imposed codes of conduct) that define ‘rules of the game’ followed by organizations. An institutional system is complete only when formal and informal institutions are taken into account (North, Reference North1990; Van Gelderen, Shirokova, Shchegolev, & Beliaeva, Reference Van Gelderen, Shirokova, Shchegolev and Beliaeva2020). According to institutional theory (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983; Scott, Reference Scott2001), in order to survive, organizations adhere to institutional isomorphism, which can be further divided into normative, regulative, and cultural-cognitive norms. In the context of doing business internationally, the role of institutional isomorphism becomes even more critical (Dunning & Lundan, Reference Dunning and Lundan2008) as MNEs face Liability of Foreignness (LOF) (Zaheer, Reference Zaheer1995) in the host countries, which they have to overcome. Therefore, management scholars have started to explore how MNE subsidiaries in foreign countries seek to gain legitimacy within the context of values and institutions of the host countries in order to overcome the LOF.

Although the concept of LOF was introduced as early as Hymer (Reference Hymer1976), it became prominent in the international management research after its further conceptualization by Zaheer (Reference Zaheer1995), who classified the sources of LOF into spatial distance between home and host countries and specificity of both countries’ environments. Not all firms face the same degree of LOF (Miller & Richards, Reference Miller and Richards2002), and a concept of psychic distance between two countries was introduced into internationalization research to refine these differences. Evans and Mavondo (Reference Evans and Mavondo2002: 519) defined psychic distance as ‘the distance between the home market and a foreign market, resulting from the perception of both cultural and business differences’. Those differences include variations in customs, educational systems, language, religion, regulatory frameworks, economic contexts, and business practices (Evans, Reference Evans2010). Although the concept of psychic distance is relatively old (Beckerman, Reference Beckerman1956), its application to international business took off only after the work done at Uppsala University during the 1970s within the framework of the Uppsala Model. Johanson and Vahlne (Reference Johanson and Vahne2009: 1415) later grounded the model in network theory, and LOF was replaced by Liability of Outsidership, defined as a position outside of the relevant network within the international context. Thus, an outsider is the opposite of an insider, the latter being ‘a firm that is well established in a relevant network’. According to Coviello (Reference Coviello2006), ‘insidership’ in relevant networks developed before an entry into a new market is instrumental to successful internationalization as it would help the firm to gain legitimacy in the host market.

Given the rising prominence of emerging market MNEs (EMMNEs) in the internationalization process in the third millennium, Mathews (Reference Mathews2006) proposed to add to OLI a complementary framework of LLL (Linkage, Leverage, Learning) according to which internationalization of EMMNE proceeds incrementally through linkages and leveraging of important resources. These resources may include informal networks such as the guanxi system of social networks and influential relationships in China, which facilitate business and other dealings (Gold, Guthrie, & Wank, Reference Gold, Guthrie and Wank2002; Lin & Si, Reference Lin and Si2010). The bazaaries networks represent a similar vital network resource in Iran.

Theories of Structure and Social Networks

The theory of structuration addresses how social systems are created and reproduced (Giddens, Reference Giddens1984). Institutions are cognitive and normative frameworks that give structure and meaning to human interaction (Scott, Reference Scott2001). According to Sewell (Reference Sewell1992), institutions are stable, continuously reproduced structures that can be divided into formal and informal. Historically, formal institutions were state and religious orders that, although changed over time, were quite self-evident at any given moment. Informal institutions, on the other hand, were more flexible and less self-evident as they were founded on unwritten and customary laws. Examples of informal institutions include trade diaspora, urban networks, and extended families. Informal institutions shape the habits and expectations of the individuals within them, and form their interactions with others. Such institutions often have regional focus but also may operate over very long distances. They can exist on a very large scale or be quite small, with smaller structures nesting within the larger ones.

Behavioral modification through institutional regulation is needed in order to avoid anarchy, chaos, and unrest. At different times in history, various institutions played central roles in this process by regulating individual behavior through either formal or informal institutions depending on the power of the institution and the level of formality. The relative strength of both formal and informal institutions is quite dynamic and thus needs to be taken into consideration. In his in-depth study of formal and informal networks in the Middle East (Egypt, Lebanon, Iran), Denoeux (Reference Denoeux1993) concludes that the absence, or weakness, of the formal institutions in a country, gives rise and strengthens the informal networks, and allows them to reassert themselves through collective actions.

Social network theories examine the structure of relationships between social entities (Wasserman & Faust, Reference Wasserman and Faust1994). Ringrose (Reference Ringrose2006) refined the definition of informal institutions by dividing them into affinity networks – networks that are tied together through a web of informal links based on affection, belief, family devotion, and value systems (e.g., Jewish and Armenian diaspora, some social clubs, Catholic missionaries), and urban networks – networks that describe patterns created by many transactions of those who inhabit the affinity networks (Ringrose, Reference Ringrose2002). It is important to note that an affinity network only develops if people are able and willing to work together towards the accomplishment of a shared objective and cooperate towards a common goal. For example, the ‘guilds’ sought after by so many scholars, were not considered an affinity network in the Middle East until modern times because they did not represent a real association (formal or not) that was capable of an action in its interest (Apaydin, Reference Apaydin2015). By the same token, immigrants to a certain country would not constitute an affinity group until they become bonded together through a desire to reach a specific mutual goal. In medieval Spain, Andalusian composite group identity was developed as a result of the presence of various affinity networks driven by a certain level of group needs (Apaydin, Reference Apaydin2014).

Moreover, the nature of network association can change over time, allowing affinity networks to become formal institutions (e.g., the early Muslims started as an informal association and ended up as a cohesive civilization). However, formalization is not always a positive development for the affinity networks as it may carry the risk of losing the initial bonds that tied members together, as in the historical example noted by Apaydin (Reference Apaydin2016). In sum, such networks stay effective as long as they do not deviate from the original basis on which they were formed. The Jewish diaspora, for example, has thrived through the ages in its original informal configuration. In sum, having a common purpose is more important than transforming the network into an organized structure.

Although social network theory has a strong quantitative strait and a specialized journal (Social Networks), which studies structure of human relations and associations that may be expressed in network form using computer modeling, the scope of our article is more conceptual and qualitative, as case study research enables a deeper, more profound understanding of the nature of the phenomenon (Yin, Reference Yin1994). In the context of the Middle East, the following informal networks were identified by Denoeux (Reference Denoeux1993): patron-client, occupational, religious, and residential. We focus on two types of these networks as operated in Iran, bazaaries (local merchants) and ulama (religious scholars) and their interaction within the framework of commercial activities, referentially anchored at the location of a local bazaar. We explain the Iranian context before elaborating on the role that these networks have played drawing implications for international business.

LOCATIONAL CONTEXT

The Middle East and Islamic Asia regions have been relatively understudied in the past, which led some scholars to call for more extensive research on these regions (e.g., Carney, Reference Carney2013). With an increased globalization of the third millennium, both business practitioners and academics have started to turn to the region more and more. Hofstede (Reference Hofstede2007: 417) notes that management theories developed in the last century in the West reflected the prevalence of individualism over collectivism in those countries: ‘I know of no theories that deal with the role of family or ethnic loyalties in management and organization’. In this article, we are attempting to start filling this conceptual lacuna.

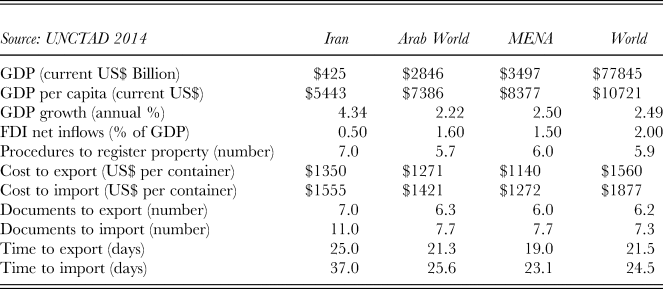

The Islamic Republic of Iran represents a particularly interesting context for our study. On the one hand, it has a large economy with a GDP of $461 billion (UNCTAD, 2017), and expected to increase – despite the US sanctions – to $518 billion in 2019 (EIU, 2019). On the other hand, until recently, it was also the most closed economy in the region. In fact, its 2011 FDI net inflows as a percentage of GDP (0.5%) was just one-third of the region average (1.5%). However, it increased to 1.17% in 2017 (UNCTAD, 2017). It is difficult to do business in this country as the main indicators of ease of doing business (days, time to register a company, number of documents to export/import, etc.) are worse than those of the region (See more detailed comparative statistics in Table 2). Nevertheless, economic reports show that some countries have been traditionally economically connected to Iran despite the abovementioned difficulties and sanctions against the country. The top five partners for Iran in 2017 were China, India, Turkey, Japan, and Taiwan (UNCTAD, 2017). Petroleum exports account for 80% of government revenues in Iran (Heritage, 2016), with China, India, Japan, and South Korea being the largest buyers of Iranian oil (Thomson Reuters, 2016).

Table 2. Comparative Business Indicators

Iran plays a significant geographic role for China as it represents a central segment of the trade route connecting China and the Middle East. In February 2016, a historic train journey from China's eastern province of Zhejiang to Tehran marked what could be considered the new ‘Silk Road’. Despite the US sanctions on Iran, China's crude imports from Iran have remained strong. In May 2019, for example, China took about 80% of Iran's liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) exports (Sundria & Murtaugh, Reference Sundria and Murtaugh2019). In 2018, China imported about $15 billion worth of crude oil from Iran (Workman, Reference Workman2019).

In return for oil, China supplied Iranian markets with inexpensive consumer goods and made investments in non-oil sectors such as manufacturing and construction (Bliler, Reference Bliler2015). In the oil business, China has been instrumental in developing and streamlining upstream and downstream production capacities for Iran. Moreover, Chinese technological know-how is used in construction, telecommunication, and defense (Harold & Nader, Reference Harold and Nader2012). This has led some authors to note that China may have become ‘an “insider” within the Iranian economy’ (Winand, Vicziany, & Datar, Reference Winand, Vicziany and Datar2015: 297). Iran's trade with China is expected, according to the Economic Intelligence Unit (EIU, 2015), to rise from USD 51.8 billion in 2014 to about USD 600 billion by 2026.

Iran was expected to register the fastest growth in the MENA region after the lifting of sanctions. However, because of the reinstated sanctions, the Iranian economy had been suffering. China's trade with Iran witnessed a substantial drop (35%) in the first five months of 2019 (Radio Farda, 2019). The economic performance of Iran will be dependent on the political outlook, especially in terms of the standoff with the US. If an agreement is reached, leading again tolifting sanctions, the Iranian economy would be expected to grow in a sizable manner.

Irrespective of the political stalemate that seems to be currently hovering over the region, Iran remains a country with significant potential. Under normal conditions, Iran represents an attractive market for MNEs. Limiting Iran from reaching its full economic potential could be attributed not only to political factors but also to structural issues within the Iranian economy. Twenty percent of Iran's GDP is in the hands of an organized religious establishment (Nichols, Reference Nichols2016). The economy is dominated by established institutions and networks, and newcomers have to work with complicated layers of formal and informal social networks embedded within a web of commercial, religious, and political interests. This specificity creates the institutional constraints for international business we mentioned in the introductory part of our paper.

Understanding the role of these networks is essential. Iran represents a context with an unstable institutional environment that impacts corporate strategies (Farashahi & Hafsi, Reference Farashahi and Hafsi2009). While various types of networks are well covered in historical and political research, their explicit conceptual analysis is still extremely scarce in management research. Lack of understanding of how these networks operate represents a significant information gap. Much of the critical market knowledge needed to survive in contexts like Iran resides in those networks, which makes access to such markets extremely challenging (Heirati & O'Cass, Reference Heirati and O'Cass2015).

At first glance, Iranian bazaaries (local merchants) may seem to be an innocuous, mostly irrelevant, loosely coupled group of individuals who typically would not be taken into consideration when contemplating an international expansion; this is especially true given the general passivism of similar groups in other Middle Eastern countries. However, modern Iranian political history made the country an anomaly in the region. In Iran, unlike other countries of the Middle East, the bazaar has been the mobilizer, the leader, and often the catalyst of political change with subsequent implications for economic activity. In other cases, such as many Arab countries (Egypt, for example), no such role was observed. The Iranian bazaar has strategically positioned itself historically in times of political turmoil to become a major economic force in present times. We elaborate below on how such a role has developed historically, and explain factors underlying the power of this network.

THE CASE OF IRANIAN BAZAARIES

The bazaar, as a physical entity, means ‘the marketplace’. However, it has often played a fundamental role in Muslim societies which extended far beyond its physical structure. While commercial activity was not very much appreciated in the Christian West until the renaissance (Nasr, Reference Nasr2004), the merchant class has been always well regarded in Islamic history partially because the prophet of Islam was, at one point in his life, a merchant himself. A significant portion of the commercial activity during the heyday of the Muslim caliphate (roughly from the 8th to the 13th century) occurred in several important cities of that pre-modern period which were strategically positioned at the crossroads of the converging commercial routes; these were towns like Siraf, Nishapur, and Narmasir in Iran, Daybul in Sind, Mahdia in the Sahel, Cairo in Egypt, and Cordoba in the Western Mediterranean (Banaji, Reference Banaji2007).

The bazaar is typically located in a vital part of the city. It is usually distinctive in terms of adjunct buildings, including commercial offices, a grand mosque, and other structures. It is often designed in a linear form, as this creates a flow of fresh air moving freely within such pathways, with shops situated on both sides. Sometimes, however, it would stretch over the city center. In addition to shops of various sizes, the bazaar hosts areas for worship, food, and other activities such as the public bath (Bonine, Reference Bonine1990). The mosque proximity to the bazaar facilitates communication between the commercial and the spiritual, an interaction that has played a significant role in Iranian history (Mozaffari, Reference Mozaffari1991).

The bazaar has also been at the center of social and political forces operating within Iranian society (Amineh & Eisenstadt, Reference Amineh and Eisenstadt2007). The bazaar basically represents the petit-bourgeois class of society (Mozaffari, Reference Mozaffari1991), including people involved in various trade activities such as retailers, wholesalers, dealers, currency brokers, and influential businessmen. It is worth noting that the bazaar does not represent random collections of disorganized merchants but rather an affinity network that, at various points in Iranian history, was instrumental in the process of social and political change (Ayazi, Reference Ayazi2003).

The relationship between the bazaaries and the ulama (religious scholars) is well documented (Ashraf, Reference Ashraf1988; Keddie, Reference Keddie1983). Shi'a ulama have historically been a fundamental force in Iranian political history (Moaddel, Reference Moaddel1986), and their relationships with bazaaries are characterized by mutual interdependency. The bazaar, which represents the economic interests of the merchants, traders, and their integrated networks, has long realized the ulama's power and, accordingly, a close association has existed between the two networks. The bazaaries operate according to a set of unwritten rules stemming from tradition, inherited customs, and Shi'a religious thought (Mozaffari, Reference Mozaffari1991). This explains how the bazaaries function, how they make deals and complete contracts, and how they settle disputes. The bazaaries have to depend on the ulama to offer them the moral legitimacy and guidance for the ways they conduct commercial transactions. The bazaaries also need the ulama to legitimize financial transactions and increase their financial credibility (Mansourian, Reference Mansourian2007). The ulama act as a sort of certifying agency for bazaaries to get credit for their commercial activities, and they would naturally give much credence to those who fulfill their religious obligations, such as the payment of religious taxes (Mansourian, Reference Mansourian2007). Because of their proper qualification in Islamic Law, the ulama are the most equipped to settle commercial disputes that inevitably emerge in day-to-day transactions (Skocpol, Reference Skocpol1982). The bazaaries care for their economic well-being but, in general, have tended to exhibit social attitudes that did not threaten the ulama. Likewise, the ulama care for the type of political and social systems that govern Iran, but at the same time are conscious of the importance of economic policies that do not threaten their finances. It is also evident that this interdependency was strengthened by social integration due to family ties (Amineh & Eisenstadt, Reference Amineh and Eisenstadt2007).

Throughout Iranian history, the conflict between the state and the bazaar seemed to escalate over many issues, including the desire to control Iran's markets, a conflict that often resulted in demonstrations, strikes, bazaar invasions, and arrests (Mazaheri, Reference Mazaheri2006). This was accompanied by two important societal changes which contributed to the growing importance of the bazaar, one demographic and the other economic. The first change related to the increased urbanization of Iranian society (Nashat, Reference Nashat1981). The second change was economic, as local and regional bazaars gradually came together into the semblance of a national market linked to markets beyond Iran's borders. This particular change was not exactly without precedent, as Iranian merchants had bought and sold in international markets for centuries. What was new was the depth of involvement in business activity that became global in nature. What was earlier a group of dispersed traders with varying interests and no clear economic or political agenda, developed into a capitalist class (Nashat, Reference Nashat1981) that was destined to significantly contribute to many future revolutions, changing the face of Iranian history. The bazaaries converged into a powerful network that was instrumental in effecting change in Iran's social and political space.

If one follows the sequence of events that led to the 1979 revolution, which replaced the monarchy with a religious rule, it becomes evident that the ulama, the most vocal of whom was Khomeini, were mostly opposed to the Shah. Although the bazaaries were not happy with all of the Shah's policies, they were nevertheless not as distressed at the beginning. The economic period from 1963 to the early 1970s was economically prosperous with increasing oil prices. GDP per capita grew tremendously, but this was not coupled with an improvement in the standard of living for the average Iranian household (Esfahani & Pesaran, Reference Esfahani and Pesaran2009). While some continued to reject the Shah's programs, others became more restrained, trying to play the new game by modernizing their operations (Bayat, Reference Bayat1998). It was not until the mid-1970s when inflation hit hard, and the Shah responded by ill-thought policies of price controls, that the bazaaries, one more time, aligned themselves with the opposition of the ulama.

The post-1979 system in Iran seems to stand on three pillars; political affairs are controlled by the ulama, the military space is possessed by the Revolutionary Guards, and the commercial space is led by the bazaaries (Mozaffari, Reference Mozaffari1991). The ulama, however, have the supreme authority in all spheres and their dependency on the bazaar that was present before the revolution is now subject to a different dynamic (Mansourian, Reference Mansourian2007). On the one hand, bazaaries are represented in the political structure in Iran (Mozaffari, Reference Mozaffari1991), which is a sign of increasing political influence. On the other hand, the religious class in Iran, which is very conscious of the potential destabilizing role played by the bazaaries, seems to keep an eye out for any increase of the bazaar's power that might impact another round of political change in Iran. While any disruptive political role for the bazaaries is for the future to reveal, what is clear is that the bazaar was, and still is, motivated primarily by economic interests.

The Uniqueness of Iranian Bazaar

The Iranian bazaar has been an exception in the Muslim world, where its contribution to change has manifested itself at several junctures in Iranian history. Within this context, one can understand the absence of the bazaar as a driving force for change in Sunni[Footnote 1] Muslim contexts, or in other Shi'a contexts such as Iraq and Azerbaijan. This was historically the case, and this has also been the case in the recent Arab revolts (2011–2012). While growing economic gaps, towering unemployment, widespread inflation, elevated economic scarcity, and the alienation of certain classes have prompted people to act (Amuzegar, Reference Amuzegar2012), Arab revolts were not masterminded or driven by a bazaar class. The Iranian bazaar is not only a socio-economic unit; it also represents a center for ‘autonomous sociopolitical opposition’ (Haghighi, Reference Haghighi2018). We explore below some factors that may have caused such an unprecedented role for the bazaar in Iran compared to other Muslim contexts.

The first factor is related to the bazaar's composition in addition to the economic role it played in the Iranian economy, as explained earlier. The state's inability, at least until 1979, to influence bazaar dynamics and networks, specifically its interaction with the ulama, positioned the bazaaries as a key player in Iranian politics. Other societal classes within Iran were not able to match the bazaar and its networks, a case without precedent in other Middle Eastern contexts. The Iranian bazaar has always been a homogenous group dominated by Shi'a Muslims (Keddie, Reference Keddie1983). This is in contrast to other bazaars in the region where non-Muslims played a significant economic role (Gilbar, Reference Gilbar2003). In Egypt, for example, two non-Muslim minorities were notably active during the nineteenth and early part of the twentieth century. First were the local Egyptian Jews and Christians who, though fewer in numbers than their Muslim counterparts, engaged actively in commercial life. The others were the local foreign minorities, the Greeks, Armenians, Italians, and other European nationals who immigrated to Egypt and became part of its fabric (Deeb, Reference Deeb1978). In a city like Alexandria, for example, the second half of the nineteenth century saw the presence of a very active non-Egyptian population (Reimer, Reference Reimer1988). In addition to Syrian and Lebanese Christians (Hourani, Reference Hourani1991; Reimer, Reference Reimer1994), Jewish merchants from Europe settled in Egypt in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and they assumed significant financial and commercial posts (Hathaway, Reference Hathaway1997). This heterogeneity of the Egyptian merchant class meant that Egyptian merchants as a social entity didn't represent an affinity network; they lacked cohesion, and were thus ill-prepared to engage in political action: ‘The preponderance of non-Egyptian communities in commerce emphasizes […] the weakness of the indigenous Egyptian merchant class’ (Reimer, Reference Reimer1994). On the contrary, because of its relative homogeneity in Iran, the bazaaries network was able to stand up as a formidable force continuously resistant to outside infiltration attempts. Other bazaars in the Middle East in cities like Cairo and Damascus were more tolerant of foreign competition, which was not true of the Iranian bazaar community.

Another reason for the bazaar's significance as a political force is related to the historic incapacity of any central government in Iran to infiltrate the bazaaries – ulama social networks. The 19th-century Qajar rulers were fundamentally weak and had to invite foreign interventions only to succumb later to internal pressures and revolts. The Shah's solid grip on the bazaar in the 20th century and his attempts to subdue the ulama met with fierce resistance, which eventually led to his overthrow. The dynamics of the relationship between the bazaaries and the ulama did not allow for any effective state control; both had an interest in weakening the state's position vis-à-vis the bazaar. Incomes of Shi'a ulama were mostly independent of the state as the bazaaries constituted an important, though not exclusive, alternative source of clerical finance. Shi'a ulama represented a social class that collected taxes, consolidated powers, and, in many ways, assumed roles normally belonging to the state. When the government became weak, which was the case in Qajar Iran, they grew even more powerful. When the state got stronger, and such was the case during Pahlavi's period, the ulama felt threatened by the state's attempts at compromising their economic or social powers, and they mobilized, resisted, and involved themselves directly in political action.

Sunni ulama, on the other hand, primarily depended on the state itself for financing and thus had no interest in weakening it. Sunni ulama in Egypt, for example, since the reign of Muhammad Ali (1805–1848) have been part of the state system, and it is the state, not the ulama, that has more control over waqf (religious endowments) and control of mosques (Moustafa, Reference Moustafa2000). Rulers often had to accommodate the religious requests from the Sunni ulama in terms of ensuring societal conservatism and keeping social relations in order. Those ulama, however, did not act as a substitute for the government or its institutions in such activities as collecting religious taxes or resolving commercial disputes. Moreover, Sunni ulama traditionally objected to rebellion against oppressive regimes: ‘Following a long tradition of political theory and practice, the ulama objected to rebellion against the rulers, even oppressive ones, and preached the doctrine of obedience, since “one day of civil strife (fitna) is worse than 40 years of tyranny”, as an old and well-known saying put it’ (Winter, Reference Winter2003: 107). This led Sunni ulama, in many other parts of Sunni Islam, to rarely rebel violently against their rulers. Rulers have thus habitually been able to co-opt an important sub-section of the religious structure that could have otherwise been more prone to political action. Grievances often targeted abusive governors or tax officials, but they would exclude the Sultan himself from such protests. ‘Though the ulama and merchant classes would resist the state, their long-term interest depended on the preservation of a stable military order’ (Lapidus, Reference Lapidus1984: 153). There is no indication that the ulama, in Sunni localities, depended on the merchant class for collecting religious taxes as was the case with Shi'a ulama in Iran. Thus, the bazaaries-ulama alliance characterizing Iranian social and political space did not repeat itself in other regional contexts.

Even in other Shi'a contexts, one does not notice the influential role that the bazaar played in Iran. In Azerbaijan, the Shi'a ulama had ‘neither the substantial financial autonomy its counterparts enjoyed in Iran nor the strong traditional ties with the bazaar’ (Nfa, Reference Nfa2014). In Iraq, the situation is a little bit different. Historically, the bazaar did not play a role that is similar to the one played in Iran. There was no powerful merchant class in Iraq to hold a reasonable alliance with the ulama, who in turn were significantly weaker compared to their counterparts in Iran. Finally, the merchant class in Iraq was not dominated by Shi'a as the most powerful merchants were not Shi'a (Cline, Reference Cline2000). In Bahrain, the politics of the country during the British presence, revolved around ‘a complex web of client-patron relations between the ruling family, the British, and the merchant class’ (DeGeorges, Reference DeGeorges2010). Later on, as some scholars assert, the political role of the merchant class almost completely disintegrated. Comparing such cases, the Iranian bazaar truly stands as an exceptional phenomenon even when compared with other Shi'a communities.

Contrary to the Iranian bazaar, the merchant class in many Muslim localities did not develop as a distinct social class or an affinity network with its own agendas and programs. Instances of protests or revolutions in a country like Egypt witness that the merchant class did not emerge as a homogenous force. In 1882, for example, the main driving forces of the Alexandria riots were the prosperous peasantry, the Egyptian officer corps, and a Muslim faction impressed by the rhetoric of Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, a famous non-Egyptian scholar residing in Egypt (Reimer, Reference Reimer1988). Likewise, the 1952 revolution was masterminded by a small group of soldiers, later known as the Free Officers, who mostly came from peasant backgrounds. Merchants seemingly have never had the chance to develop independently of the state. In many Muslim cities since the Middle Ages, merchants were very much reliant on the state in running their affairs (Lapidus, Reference Lapidus1984).

In sum, there has never been room for the bazaar to assume a political leadership role in Sunni Islam where the political authority of the state has been preeminent. In such contexts, strong central governments were frequently able to maintain order and monitor the bazaar, tax it, and control weights and measures. Besides, there is revulsion in Sunni Islam against political disorder and attraction to legitimizing authority. This is in contrast with Iran, where only in a few instances in history was the bazaar subordinated, and if done, it was only done for a short period and often met with stern resistance. The Iranian bazaar, because of its cohesion and network connections with religious leaders who refused to acknowledge any automatic legitimacy for an existing government, was well-positioned to assert itself in times of political and economic turmoil.

The historical case study presented in this section amply demonstrates the uniqueness of the Iranian bazaaries as a strong, cohesive informal affinity network which was able to exhibit its political and economic power time and time again. In the next section, we build on this historical evidence to develop a conceptual model and suggest a series of propositions regarding the role of the bazaaries in the context of international business.

CONCEPTUAL MODEL

The above description depicts the bazaaries as representing an influential and prominent player that MNEs need to account for. We thus proceed by presenting our conceptual model outlining a set of propositions grounded in the theories of international business (OLI and LLL) and social network theories.

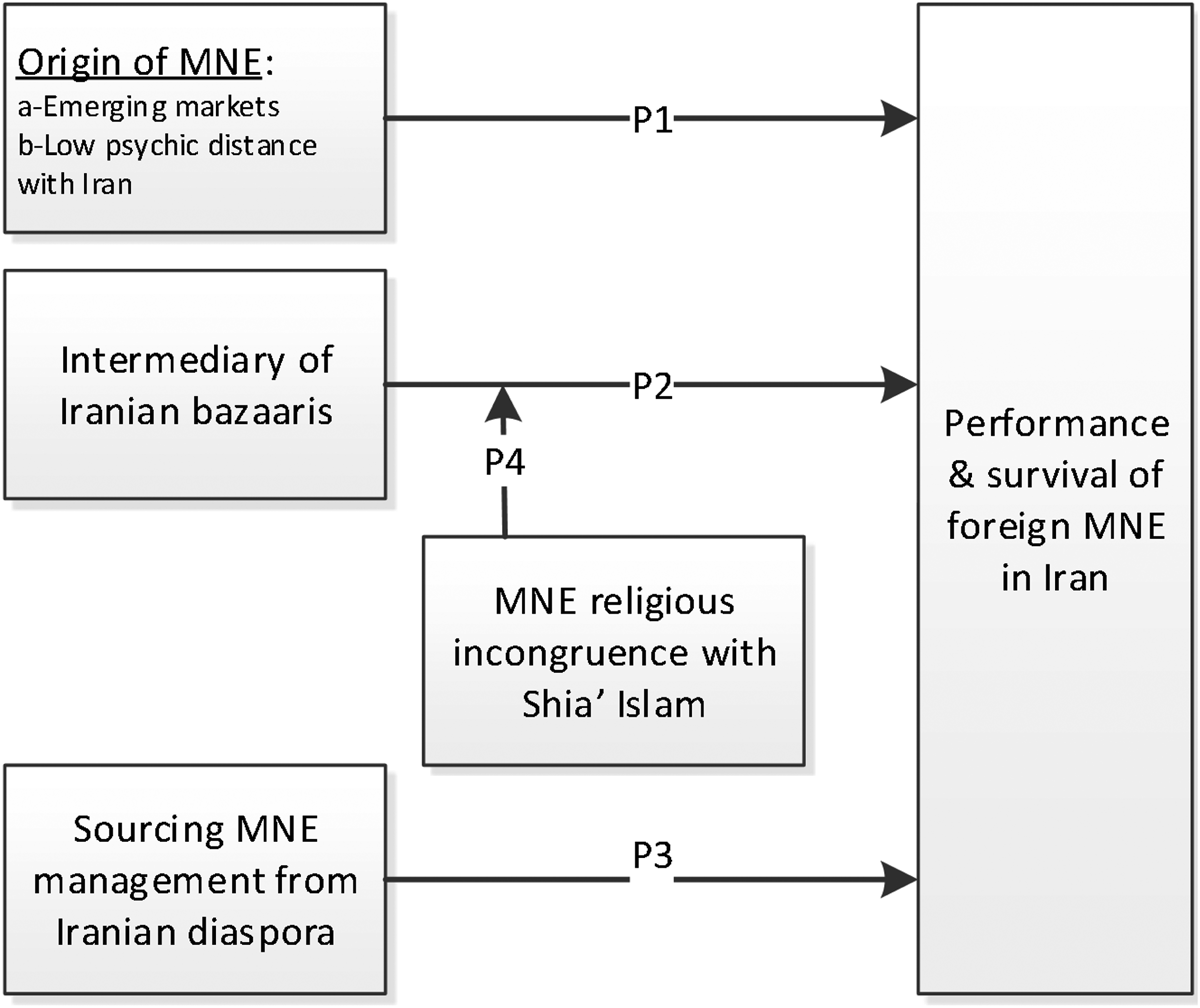

In order to provide continuity and build upon the extant theoretical base, we provide an introductory P1, which consolidates already established theoretical relationships between the origin of MNE and the success of its foreign entry in Iran. In doing so, we specifically focus on (a) the economic status of the country of origin (developed vs. emerging markets) and (b) the psychic distance between MNE home country and Iran. We then develop two new propositions (P2 and P3) grounded in the social network theories which constitute our contribution to this theory. The final proposition (P4) clarifies an additional aspect of the country of origin variable in the peculiar context of Iran's religious orientation explained in the case study section of this article. Our propositions are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Conceptual model

The theoretical and managerial implications of those propositions are then described in the final section of the article.

The Role of Country of Origin

The role of the country of origin of an MNE in the success of a foreign entry has been well established in the early studies in the international business field (Dunning & Lundan, Reference Dunning and Lundan2008; Hymer, Reference Hymer1976; Zaheer, Reference Zaheer1995) as described in the introduction. We want to highlight only two more recent aspects of this multi-dimensional construct, the degree of economic development of the home country and the psychic distance from Iran in order to provide continuity and the proper grounding platform for our main propositions that will follow.

MNEs from emerging markets (EMMNEs) represent a new phenomenon. Until 1980, the home country of an MNE was in North America, Western Europe, or Japan. However, recently we witnessed a rise of EMMNEs, first starting with South Korea, followed by China and other BRICs countries, and now about one-third of MNEs are from emerging markets (UNCTAD, 2013). EMMNEs represented 53% of all global M&A in 2013 (Demirbag & Yaprak, Reference Demirbag, Yaprak, Demirbag and Yaprak2016). These firms enjoy advantages because they learned to operate in underdeveloped environments of their own countries (Aharoni, Reference Aharoni, Demirbag and Yaprak2015).

Mathews (Reference Mathews2006) proposed that while developed countries MNEs have their international advantage grounded in OLI framework, EMMNEs build their advantage on a fundamentally different basis, which he calls LLL (Linkage-Leverage-Learning) framework. According to this argument, EMMNEs build linkages and leverage their and others’ resources and learn along the way. Consequently, they are better adjusted to the interlinked dynamic character of the modern networked economy. EMMNEs thus are better able, we suggest, operating in institutional contexts that require linkages to networks of influence such as the bazaaries of Iran. Trade evidence suggests that EMMNEs from the Arab Gulf countries have been able to establish a presence in Iran through leveraging those relationships. This is despite the political differences that would suggest the contrary. Therefore, we argue:

Proposition 1a: Foreign EMMNEs will have better performance and survival rates in Iran than developed market MNEs.

Understanding the development status of the MNE home country is important given that Iran itself is on the early emerging path. Yet what differentiates it from other emerging markets is another important well-established variable of psychic distance. Psychic distance refers to the distance between the home market and a foreign market, and includes both cultural and business differences. So, in addition to Hofstede's cultural dimensions, it includes business aspects such as legislation, politics, economic conditions, market structure, and business practices (Evans, Reference Evans2010). Since Hofstede's (Reference Hofstede1980) cultural values framework (CVF) was published, researchers have utilized it extensively in their cross-cultural studies. Although this CVF has been criticized for reducing culture to just a few dimensions, ignoring within-country cultural heterogeneity and the changing nature of the culture and limiting the sample to a single MNE (Sivakumar & Nakata, Reference Sivakumar and Nakata2001), researchers continued using it because of its clarity, parsimony, and resonance with managers (Kirkman, Lowe, & Gibson, Reference Kirkman, Lowe and Gibson2006). The meta-analysis conducted by these authors suggests that country differences exist due, in fact, to cultural values, and thus culture may be used as a mediator, but should be combined with other appropriate variables. Therefore, recognizing the limitations of CVF, we propose to use a more diversified psychic distance which includes not only Hofstede's CVF but also business and communication aspects.

Communication and cooperation between two low-context cultures, such as the USA and Germany are significantly easier than between two high-context cultures such as China and Iran because in low-context cultures details are explicit, while in the high-context culture details are culturally embedded and thus often may be misunderstood because of the large psychic distance. Usually, firms pursue internationalization in an incremental manner. They make first an attempt to penetrate markets that are psychically comparable before attempting to expand into more distant foreign markets (Evans, Reference Evans2010).

One example of the importance of psychic distance relates to the concept of high- and low-context cultures, which was first introduced by Hall (Reference Hall1976) and then extensively used in various country studies. Hall's theory is different from Hofstede's cultural dimensions as it focuses specifically and exclusively on communication styles, while Hofstede's framework addresses a larger range of individual behaviors and does not include communication aspects of the culture. In low-context cultures, communication is explicit, and words are important. In high-context cultures, small signs and behaviors are more important than words. Generally speaking, Western countries represent low context, and Asian countries, including Iran, – high-context environments. Cultural affinity has been theorized to be an essential aspect of psychic distance. Thus, an MNE from a developed low-context country needs to adapt to a higher-context host. Higher-context cultures expect small, close-knit groups, and reliance on these groups. Professional and personal lives often intertwine. Managers who are aware about high context cultures are more likely to try to work things out through taking time to develop the relationships needed to penetrate difficult markets. On the other hand, managers from a low-context country, even when they know that informal network support needs to be sought, would find that accessing such networks is difficult. For example, managers from China would be familiar with a guanxi concept (Li, Zhou, Zhou, & Yang, Reference Li, Zhou, Zhou and Yang2019) in their own country, and will be able to recognize the need to find a network of influence in another high-context country such as Iran.

The Iranian context provides an interesting example of how the psychic difference can be successfully managed by MNEs. Some MNEs hire managers who are able to bridge the distance between an MNE and its operations in Iran. Companies, for example, have found it advantageous to capitalize on the Lebanese talent to access Iran (Abdel-Sabbour, Reference Abdel-Sabbour2014). Not only both countries are considered to have high-context cultures, the psychic distance between Lebanon and Iran is smaller compared to other countries. While the two countries differ in terms of ethnicity and political systems, they share other aspects of their cultures that reduce the psychic distance, such as some traditions, political orientations, and economic interests. Accordingly:

Proposition 1b: The degree of the psychic distance between foreign MNE's home country and Iran will have a significant negative effect on the performance and survival of a foreign MNE in Iran.

Development of Network Affiliation

Theory development in social sciences tends to progress from general to more specific. For example, in the context of international management research, the notion of LOF was first introduced as a conceptual idea (Hymer, Reference Hymer1976), and then its dimensions (sources of foreignness) were developed and refined (Zaheer, Reference Zaheer1995). Later, it was proposed that MNEs may face different degrees of LOF depending on the psychic distance between host and home countries (Miller & Richards, Reference Miller and Richards2002), and that the degree of LOF influences the mode of entry decisions (Chen, Griffith, & Hu, Reference Chen, Griffith and Hu2006). Finally, LOO (Johanson & Vahne, Reference Johanson and Vahne2009) was introduced to take into account the networked nature of the modern business environment.

Similarly, while institutional theory required local isomorphism (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983) to gain legitimacy and face LOF, later research (Yildiz & Fey, Reference Yildiz and Fey2012) proposed alternative mechanisms to gain legitimacy. Following their lead, and building on a more contemporary concept of LOO, we propose to refine the Uppsala model, which recognizes either outsidership or insidership, by introducing a position of an ‘intermediary’ – a proxy network position which facilitates the relationship between an outsider and an insider for cases when formal insidership is not possible due to the institutional constraints discussed above.

Generally, network-based discussions are still relatively new in international management research, so the positions are generally assumed to be binary (in or out). Recall Johanson and Vahlne's (Reference Johanson and Vahne2009: 1415) definitions: an insider is ‘a firm that is well established in a relevant network’, while outsider is ‘a position outside of the relevant network’. If a firm attempts to enter a foreign market where it has no relevant network position, ‘it will suffer from the liability of outsidership and foreignness, and foreignness presumably complicates the process of becoming an insider’.

Moreover, the Uppsala model implicitly assumes that transformation from ‘out’ into ‘in’ is, although difficult, still possible. Hohenthal (Reference Hohenthal2001) warns us that it may take time, as long as five years of managerial effort, to create new working relationships, and many attempts fail. We would like to explore the boundary conditions of those assumptions based on the findings of the empirical case of the Iranian context presented in this paper. As explained in the case, Iranian bazaaries, unlike similar groups in the other part of the Middle East, represent a cohesive homogeneous group of Shi'a merchants historically proven to be capable of an economic or even political action. As such, they are de facto the main actors and the gate-keepers of the economic activity in Iran, a position which they enjoy under the patronage of the country religious authority of the ulama received in exchange for the financial benefits. Accordingly, we argue that, given that commercial and religious interests in Iran are so firmly and intrinsically intertwined, it would not be possible, for a complete ‘outsider’ to obtain insidership in Iran unless going through the intermediary of the bazaaries.

While we use the Iranian case as a starting point, our discussions and conclusions do not only pertain to this specific context. We argue that the implications of our discussions extend beyond the specific case of Iran that would explain implications of informal network dynamics in a variety of situations in the Asia region in general, where similar types of informal networks have been historically quite active. So MNEs have to consider the possibility that, in some contexts where local networks have strong and intertwined interests, it may be challenging, if not impossible, for a complete ‘outsider’ to obtain insidership in any way other than by going through the intermediary of those networks.

The Role of Informal Networks in Unstable Institutional Environment

Until recently, the majority of the early internalization studies were conducted in developed markets and only occasionally in the emerging economies (Farashahi, Hafsi, & Molz, Reference Farashahi, Hafsi and Molz2005). One of the underlying assumptions in such studies was an alignment between firm interests and institutional structures. However, these assumptions are inadequate in emerging or developing contexts in which cause-effect relationships are not clear, and economic norms are uncertain (Newman, Reference Newman2000). In such environments, managers mostly rely on informal relationships with authorities and engage in political deals to increase their chances of survival (Hillman & Hitt, Reference Hillman and Hitt1999) in addition to strengthening their relationships with other market players to gain valuable market knowledge (Prashantham, Zhou, & Dhanaraj, Reference Prashantham, Zhou and Dhanaraj2020). These network relationships become imperative for success (Peng & Heath, Reference Peng and Heath1996; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Peng, Reference Peng2003: Peng & Zhou Reference Peng and Zhou2005). Moreover, political connections affect firm profitability in such economies (Tian, Hafsi, & Wu, Reference Tian, Hafsi and Wei2009).

The Iranian bazaar presents an excellent illustration of this point. For example, Farashahi and Hafsi (Reference Farashahi and Hafsi2009) studied the textile industry, the second largest after the oil sector in Iran. They identified four types of managers in this industry, with bazaaries being specifically a distinct leading category enjoying high reputation and high behavioral consistency. They were more concerned with international competitiveness than managers of other categories, and their firms boasted better performance than those of their competitors. In general, the bazaaries are aware of their role in facilitating access to international firms, and they resist attempts aiming at compromising such a role. When the Shah of Iran tried to change the impact of the bazaaries, they joined forces with other factions of the opposition, and they were able to overthrow him. Later, their power persisted, although the current political forces have been largely successful in co-opting them and infiltrating their networks. Accordingly, unless they are able to get through the right networks, foreign MNEs entering Iranian market will have a significant disadvantage vis-à-vis local firms. We suggest that such a disadvantage can be offset by affiliation with an appropriate insider network of bazaaries.

To elaborate on the mechanism underlining this proposition, consider that Iranian bazaaries, as explained in the preceding section, represent the main commercial network of the country with power vested in them by the religious authorities financially benefiting from bazaaries’ commercial activities. Moreover, the bazaaries are fully aware of their role in facilitating access to international firms, and they resist attempts aiming at compromising such a role. Therefore, on the one hand, they would try to obstruct independent internationalization attempts by foreign MNEs using their patrons’ power; and on the other hand, they would welcome an opportunity to become an intermediary of foreign MNEs as it would help them to prosper and reaffirm their gate-keeping position. In summary, while Iranian bazaaries represent a barrier to independently entering MNEs, they are also enablers for those willing to use their services.

Proposition 2: Foreign MNEs accessing the Iranian market through the intermediary of the Iranian bazaaries will have better performance and survival than MNEs without such intermediary.

The Role of Iranian Diaspora

A diaspora is an ethnically based affinity network (Ringrose, Reference Ringrose2006) held together by informal bonds of affection, belief, family loyalty, and common purpose, which is located away from its original place of settlement (e.g., Jewish and Armenian diasporas). According to Contractor (Reference Contractor2013), a diaspora can constitute a competitive advantage for MNEs in the country of their origin. Not only diaspora members can act as network agents, they also can provide talented employees and capital. The Iranian diaspora has developed closely-knit networked communities based on dearly shared values related to homeland and identity which impacts business opportunities (Ghorashi & Boersma, Reference Ghorashi and Boersma2009).

Iranian diaspora is one of the largest in the world (after Chinese and Indian) with an estimated 4–5 million people living outside Iran; some 1–2 million in the USA and half-million in Turkey and UAE each, in addition to other countries (Hakimzadeh, Reference Hakimzadeh2006). Iranian diaspora emergence is usually associated with the 1979 Islamic revolution. Its combined net worth was $1.3 trillion in 2006. Iranian expatriates had invested between $200 and $400 billion in the United States, Europe, and China, but almost nothing in Iran. In Dubai, Iranian expatriates have invested an estimated $200 billion. However, it is expected that the situation would reverse if sanctions are lifted (Finn & Jewkes, Reference Finn and Jewkes2016). Therefore, we propose that:

Proposition 3: Foreign MNEs owned/managed by Iranian diaspora will have better performance and survival rates in Iran than those without the diaspora component.

Boundary Condition of Congruence

The studies of formal and informal networks in the Middle East (Denoeux, Reference Denoeux1993) have demonstrated the incompatibility of some of the networks based on their religious or sectarian affiliation. Interestingly, this incompatibility is sometimes more acute among the sub-groups within the same religious doctrines (Islam, Christianity) than among groups of different doctrines. For example, the relationship between two Muslim groups of Shi'a and Sunni may exhibit more animosity with each other than either of them with Christian groups. In multi-sectarian Lebanon, different strains of Shi'a Islam have made associations with some groups of Christians (Aoun's Free Patriotic Movement), while Sunni forged affiliations with others (the Lebanese Forces and Kataeb parties).

Therefore, we propose to generalize this tendency by categorizing networks into ‘congruent’, ‘incongruent’, and ‘neutral.’ Congruent networks will have the same religious-sectarian affiliation, and incongruent will have the opposite. The neutral network will represent non-religious network and thus has no affiliation. These neutral networks are therefore well-positioned to serve as an intermediary of the incongruent relationship.

In the context of Iran, the formal institutions adhere to Shi'a Islam, and thus it would be challenging, if not impossible, for a Sunni-affiliated MNE (e.g., from Saudi Arabia) to gain an ‘insider’ position in such context. On the other hand, bazaaries, a merchant class of the country, generally hold economic and not religious interests. Therefore, they can potentially serve as an intermediary of an ‘incongruent’ MNE's internationalization efforts. We formalize this theorizing in the following proposition, which can be further explored in future research:

Proposition 4: The intermediary role of the Iranian bazaaries will have a more significant effect on the performance and survival of a foreign MNE in case of incongruence between MNE's religious affiliation and Shi'a Islam, than in the case of congruence.

DISCUSSION

Our article discussed how informal social networks can assist multinational firms in their internationalization strategy. We proposed a refinement of the Uppsala internalization model (Johanson & Vahne, Reference Johanson and Vahne2009) grounded in the network theory, to help mitigate the Liability of Outsidership (Johanson & Vahne, Reference Johanson and Vahne2009), a replacement of the Liability of Foreignness (Hymer, Reference Hymer1976; Zaheer, Reference Zaheer1995) in the modern networked business world. We contribute to the theory in three ways. First, in line with network theory, we propose an intermediary position, an agent representing the interests of the ‘outsider’ in cases when becoming an ‘insider’ is impossible due to certain institutional limitations. Second, within the context of Iran, we identify a specific informal network of merchants (bazaaries) who could play the role of such an intermediary. Third, we offer a series of propositions, which explain the role of proposed social network agents. In addition to re-affirming the importance of the MNE country of origin (emerging markets, and low psychic distance with Iran), we propose that an intermediary of the Iranian bazaaries will have a positive impact on performance and survival of the MNE's subsidiary in Iran, especially in the case of incongruence of MNE's leadership with Shi'a Islam. Additionally, we suggest that employing the Iranian diaspora may also improve subsidiary performance and survival. We contribute not only to research addressing the role of bazaaries’ network in Iran, but also towards understanding informal social networks in other contexts such as guanxi in China or yongo in Korea. Therefore, our article has several theoretical contributions, especially in relation to the Uppsala model, which we enhance by suggesting that liability of outsidership variable is not binary but may include an ‘intermediary’ position between an insider and an outsider.

Implications for Doing Business in Iran and Asia

In addition to the theoretical contributions, our article has significant practical implications. The uniqueness of the Iranian affinity network of bazaaries has a long-ranging implication for foreign agents in the country, be it individual traders and entrepreneurs, foreign companies, or MNEs. As this article amply demonstrated, bazaaries are an important political force which has inherent economic interests. Thus, it is generally advisable to seek their formal or informal affiliation and support, especially at the initial stages of internationalization, and especially for MNEs which have incongruent religious valence vis-à-vis Shi'a Islam. Moreover, the bazaaries’ network can be particularly useful in the preliminary environmental scanning of the market and identification of the success factors. Furthermore, given the bazaaries’ strong political influence, they may provide access to regulators and government officials in the country. On the other side, should MNE activity be perceived going against bazaaries’ interests, it might provoke fierce retaliation not only informally, but also formally if escalated up to the decision-makers at the government level.

Iran has passed over the past few years with phases where sanctions were enforced, then lifted, then enforced again recently by the Trump administration. When sanctions were earlier lifted, several professional syndicates and trade journals issued advice on how to ‘do business in Iran’. Many advised about the way to understand which sanctions were lifted and which remained, while others talked about the importance of doing proper due diligence (e.g., Spivack, Reference Spivak2016). Very few addressed the importance of the local networks in having successful ventures, although some address the importance of identifying the right ‘local partners’ (Spivack, Reference Spivak2016). The importance of the bazaaries network still seems to be neglected or at least,under-estimated. The post-1979 era has witnessed an increased blurring of the lines between the bazaaries and the ulama as more ulama became involved in the commercial bazaar activities. This only reinforces the point that the bazaar is still a force that needs to be taken into consideration when conducting international business. The best route is to look for local partners from within the bazaar elements as they best understand the delicate context and would thus help in the desired market penetration. Another way to improve the performance of MNEs in Iran is to source subsidiary management from the Iranian diaspora. Although their local connections may not be as strong as bazaaries’, yet their understanding of the local culture may prove to be an invaluable asset.

While the role of Iranian bazaaries is quite unique as compared to similar groups in the Middle East, it has striking similarities with informal social networks in East Asia. They are both egocentric-vertical and horizontal, mostly instrumental and purpose-based but sometimes sentimental and cause-based. It has its dark side of bribery, cronyism, and corruption and the positive side of loyalty, cooperation, and teamwork. Therefore, we suggest that some of the propositions that we offer for the network of Iranian bazaaries may be generalizable to other informal social networks in the region such as guanxi in China or yongo in Korea.

Limitations and Future Research Implications

Our research in this article is based on a qualitative case study of the historical role the network of Iranian bazaaries played in the political and social life of the country, and thus, no quantitative data were collected. We argued that given their increasingly important role over several centuries, we expect the bazaaries to become important players in international business activities. Nevertheless, this case approach helps in furthering our understanding regarding the roles of such networks in Iran and other similar contexts. Going forward, more quantitative research of the actual involvement of this network in international business activities is in order to test our suggestions. The propositions we developed in this article are based on previous conceptual frameworks and limited empirical research on bazaaries that exists in the literature. The development of testable hypotheses based on these propositions will undoubtedly shed more light on the issue of the roles of the bazaaries network in international business activities.

A fruitful avenue for future research may be a further comparison between bazaaries and other informal social networks in the region such as guanxi in China, yongo in Korea or jinmyaku in Japan. Given the uniqueness of Iranian bazaaries in the Muslim world on the one hand, and their similarity with East Asian social networks on the other, research may want to explore the influence of geographical proximity on evolutionary and developmental dynamics of social ties in the region.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we attempted to develop a series of propositions, generalizable for the region, about the role of informal social networks in facilitating the internationalization process in their home countries. We used the case analysis approach to explain the underlying causes of the phenomenon of Iranian bazaaries and exemplify the manifestation of this influence throughout the recent modern history. In times of political turmoil, these affinity networks mobilize towards the common goal and produce impactful and often irreversible results. Therefore, we may expect this trend to be prominent not only in the political but also in the economic sphere. Governments, MNEs, and other stakeholders should pay close attention to these affinity networks and include them in their consideration set while deciding to be proactively involved in such localities.