INTRODUCTION

Corporate social responsibility (CSR), defined as ‘actions that appear to further some social good, beyond the interests of the firm and that which is required by law’ (McWilliams & Siegel, Reference McWilliams and Siegel2001: 117), is gaining increasing attention from the public. Consequently, many corporations are now engaged in increasingly prosocial behaviors. The literature has examined CSR with reference to two main themes: specific CSR activities, such as donations (Brammer & Millington, Reference Brammer and Millington2008), environmental protection (Flammer, Reference Flammer2013), and fair treatment of and care for employees (Flammer & Luo, Reference Flammer and Luo2017); and CSR performance as rated by a third party (e.g., Kinder, Lydenberg, & Domini's rating; see Chin, Hambrick, & Treviño, Reference Chin, Hambrick and Treviño2013; Koh, Qian, & Wang, Reference Koh, Qian and Wang2014; Petrenko, Aime, Ridge, & Hill, Reference Petrenko, Aime, Ridge and Hill2016). However, the important topic of CSR disclosure, including firms’ public reporting of their economic, environmental, social, and governance performance, remains underexplored (Aguinis & Glavas, Reference Aguinis and Glavas2012).[Footnote 1] Although CSR disclosure reflects corporate accountability in supplying information to stakeholders and is strategically important, it is ‘fraught with uncertainty’ (Lewis, Walls, & Dowell, Reference Lewis, Walls and Dowell2014: 713) and incurs significant liabilities (Lyon & Maxwell, Reference Lyon and Maxwell2011). Therefore, knowledge of the kinds of firm that may decide to disclose their CSR activities is still limited.

Our understanding of CSR disclosure is further limited by a disproportionate focus on mandatory CSR disclosure in the literature. Indeed, relying on institutional theory (Luo, Wang, & Zhang, Reference Luo, Wang and Zhang2017; Marquis & Qian, Reference Marquis and Qian2014) or stakeholder theory (Donaldson, Reference Donaldson1999; Thijssens, Bollen, & Hassink, Reference Thijssens, Bollen and Hassink2015), researchers have tended to view CSR disclosure as a response to external pressure from governments, activists, and other important stakeholders (Reid & Toffel, Reference Reid and Toffel2009; van Aaken, Splitter, & Seidl, Reference Van Aaken, Splitter and Seidl2013). From this viewpoint, managers have a limited effect on CSR disclosure, which is determined mainly by external forces. However, CSR disclosure can be largely voluntary and therefore subject to managerial discretion. Upper echelons theory (Hambrick & Mason, Reference Hambrick and Mason1984) suggests that a firm's CSR disclosure is the manifestation of managerial preferences (Hemingway & Maclagan, Reference Hemingway and Maclagan2004) and depends on the freedom executives have to make their own decisions (Clarkson, Li, Richardson, & Vasvari, Reference Clarkson, Li, Richardson and Vasvari2008; Hambrick, Reference Hambrick2007). In line with this view, researchers have found growing evidence that the attributes of chief executive officers (CEOs), such as personal values (Agle, Mitchell, & Sonnenfeld, Reference Agle, Mitchell and Sonnenfeld1999), political ideologies (Chin et al., Reference Chin, Hambrick and Treviño2013), and hubris (Tang, Qian, Chen, & Shen, Reference Tang, Qian, Chen and Shen2015), significantly affect CSR performance. However, the effect of other top executives (or the top management team [TMT] as a whole) personal attributes on voluntary CSR disclosure has not yet been systematically examined.

To fill this gap, we propose a theoretical framework in which voluntary CSR disclosure is viewed as a reflection of top executives’ career experiences and ethical standards (Cho, Jung, Kwak, Lee, & Yoo, Reference Cho, Jung, Kwak, Lee and Yoo2015; Valentine & Fleischman, Reference Valentine and Fleischman2008). Specifically, we examine the influence of top executives’ academic backgrounds (e.g., university professorships) and argue that CSR disclosure involves the calculation of both costs and benefits (Verrecchia, Reference Verrecchia1983), which are uncertain and subject to managerial information processing (Clarkson et al., Reference Clarkson, Li, Richardson and Vasvari2008). Such information processing depends on managers’ attributes (Hambrick & Mason, Reference Hambrick and Mason1984). Compared with their non-academic counterparts, academic executives tend to have higher professional and ethical standards, and therefore are more likely to perceive CSR disclosure as an opportunity rather than a threat. Accordingly, we propose that firms with top executives who possess academic career experience are more likely to voluntarily initiate CSR disclosure than firms without academic top executives.

We test our framework by observing the voluntary CSR disclosure practices of publicly listed firms in China between 2008 and 2014.[Footnote 2] China's transitional market offers an ideal setting for testing our framework, for three reasons. First, CSR disclosure is a very important vehicle for information, enabling firms to differentiate themselves from others in an environment with poor CSR transparency. Firms that operate in such an environment tend to be criticized for their CSR reporting practices, such as low recognition, uneven levels of disclosure, and weak initiative and timeliness. Our study provides a timely examination of this important topic. Second, following China's policy of reform and opening up from 1978, a large proportion of listed firms in China have recruited top executives with academic backgrounds. For example, about 40% of the firms in our sample have top executives with academic experience. Third, although China is a large and complex transitional economy, Confucian culture has a strong legacy (Chan, Reference Chan2008; Ip, Reference Ip2009; Lam, Reference Lam2003), with professors and teachers traditionally serving as ethical role models. Compared with individuals in other professions, professors and teachers display higher levels of self-transcendence as a motivational value. This drives them to seek collective benefits for society at large (Li & Liang, Reference Li and Liang2015). In summary, the Chinese business environment allows us to observe many variations in the relationships between academic background and a firm's CSR disclosure.

Our empirical results provide strong support for our hypotheses. We find that firms with top executives with academic backgrounds are more likely to voluntarily disclose CSR activities than firms without academic top executives. The difference is smaller for firms that are state-owned, firms that are audited by large audit firms, and firms with more analyst coverage, indicating that the influence of academic executives is greater when factors strongly enforcing CSR disclosure, such as state ownership, big audit firms, and analyst coverage, are absent.

Our study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, it enriches the CSR disclosure literature by linking upper echelons theory with the literature on voluntary CSR, particularly in relation to executive academic experience. By demonstrating how top executives’ academic experience affects voluntary CSR disclosure, we advance the literature on the antecedents of CSR and explain why firms vary in their CSR voluntary disclosure activities. Second, we respond to Hambrick's (Reference Hambrick2007) call for more research on upper echelons theory and contribute to this theory by examining a rarely investigated but important type of career experience (academic experience) among top executives. As a significant number of Chinese firms have top executives with academic backgrounds, it is worth investigating whether the presence of top executives with academic experience influences corporate behaviors and outcomes. Third, we address the important topic of CSR voluntary disclosure in the context of China, which has recently seen a significant increase in firm misconduct, such as foodborne illnesses, environmental pollution, and product liability cases. We demonstrate that ownership design, audit firms, and analyst coverage are effective tools for improving the likelihood of CSR voluntary disclosure for firms with non-academic executives. In contrast, academic executives behave consistently in terms of CSR voluntary disclosure, reflecting their professional and ethical standards, irrespective of boundary conditions. Therefore, an academic TMT composition may serve as an alternative corporate governance tool for mitigating firms’ socially irresponsible activities. This may in turn offer a new direction for future research.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Review of Literature on CSR Disclosure

Although researchers have intensively investigated the antecedents and consequences of CSR activities and performance over the last two decades (for a review see Aguinis & Glavas, Reference Aguinis and Glavas2012; Mellahi, Frynas, Sun, & Siegel, Reference Mellahi, Frynas, Sun and Siegel2016; van Aaken et al., Reference Van Aaken, Splitter and Seidl2013), less attention has been paid to CSR disclosure. As producing and reporting information are expensive activities, firms may have many different motivations for disclosing CSR information. In addition, the regulations governing mandatory and voluntary CSR disclosure vary significantly between countries. Some countries mandate or specify certain aspects of CSR disclosure for corporations (e.g., Europe and India), whereas others have more flexibility on CSR disclosure (e.g., Brazil and China) (Wang, Tong, Takeuchi, & George, Reference Wang, Tong, Takeuchi and George2016). Therefore, firms have different degrees of discretion to disclose CSR information.

Researchers have adopted several theoretical perspectives on CSR disclosure. For example, a number of studies have suggested that firms engage in CSR disclosure to increase their legitimacy as perceived by external stakeholders. Based on the notion of a ‘social contract’, institutional theory posits that an organization's activities are limited by boundaries set by society (Gray, Kouhy, & Lavers, Reference Gray, Kouhy and Lavers1995). Consequently, organizations continually seek to ensure that their activities are perceived as ‘legitimate’ by stakeholders in society. Luo et al. (Reference Luo, Wang and Zhang2017) recently found that compared with firms without such links, firms with institutional links to the central government issued CSR reports more swiftly and at a higher quality in response to the requirements of the central government. In addition, firms in China tend to issue CSR reports more slowly and at a lower quality in provinces in which the local government places a higher priority on economic growth. Zhang, Marquis, and Qiao (Reference Zhang, Marquis and Qiao2016) showed that firms with executives with bureaucratic connections were less likely to use donations to buffer governmental pressure than firms with politically connected executives. Research has also shown that firms are more likely to engage in CSR disclosure when they have greater social exposure. For example, Alsaeed (Reference Alsaeed2006) showed that a firm's visibility (as measured by firm size) affected the level of information provided in its non-financial reports. Branco and Rodrigues (Reference Branco and Rodrigues2008) found that companies with greater public visibility were generally expected to exhibit greater concern about improving their corporate image through social responsibility disclosure.

Stakeholder theory acknowledges the role of managers in deciding to engage in CSR. For example, Donaldson explained that ‘stakeholder theory is managerial in nature’ and that ‘managers [are] the subject of stakeholder theory’ (Reference Donaldson1999: 238). However, the theory still views CSR as a reaction to external pressure from various stakeholders. From this perspective, managers respond selectively to external demands rather than taking actions that reflect their genuine values and preferences. This may not be an adequate explanation in the social response context. The values and attitudes of top managers are extremely important to strategy formation, as they guide managers to take active or negative approaches to social demand. Ullmann (Reference Ullmann1985) suggested that a firm's key decision makers could have different views on social demands and initiate different modes of response to these demands. A positive stance reflects managers’ efforts to influence their organizations’ relationships with important stakeholders. A negative stance implies that a firm is neither involved in monitoring important stakeholders nor deliberately searching for an optimal stakeholder strategy.

Therefore, studies have ignored the important point that a firm's top executives are responsible for carrying out social practices, such as disclosing CSR to stakeholders. Drawing mainly on upper echelon theory (Hambrick & Mason, Reference Hambrick and Mason1984), which posits that top executives’ attributes influence their perceptions and ways of thinking, resulting in variation in information processing regarding CSR, a growing body of research has started to examine the effects of managerial background, values, and preferences on CSR activities and performance (see Appendix A1 for a detailed review). For example, Benmelech and Frydman (Reference Benmelech and Frydman2015) found that CEOs with military experience were less likely than their non-military counterparts to be involved in corporate fraud. Chin, Hambrick, and Treviño (Reference Chin, Hambrick and Treviño2013) found that certain political ideologies held by CEOs (e.g., liberalism versus conservatism) were positively related to firms’ level of CSR. In addition, Manner (Reference Manner2010) found that employing a CEO with a Bachelor's degree was positively related to exemplary corporate social performance. Other CEO attributes, such as confidence (McCarthy, Oliver, & Song, Reference McCarthy, Oliver and Song2017), retirement (Kang, Reference Kang2016), narcissism (Petrenko et al., Reference Petrenko, Aime, Ridge and Hill2016), hubris (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Qian, Chen and Shen2015), market ideology and beliefs regarding CSR (Hafenbrädl & Waeger, Reference Hafenbrädl and Waeger2017), and career horizon (Oh, Chang, & Cheng, Reference Oh, Chang and Cheng2016), have also been shown to significantly affect firm CSR investment and performance. In terms of TMT and board attributes, the literature has shown that board diversity (Harjoto, Laksmana, & Lee, Reference Harjoto, Laksmana and Lee2015), female board members (Galbreath, Reference Galbreath2016; McGuinness, Vieito, & Wang, Reference McGuinness, Vieito and Wang2017), board members with professorships (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Jung, Kwak, Lee and Yoo2015), TMT education diversity (Chang, Oh, Park, & Jang, Reference Chang, Oh, Park and Jang2017), and TMTs’ integrative complexity and decentralization of decision making (Wong, Ormiston, & Tetlock, Reference Wong, Ormiston and Tetlock2011) all have positive effects on firms’ CSR engagement or performance.

Researchers have only recently begun to explore the effects of managerial attributes on CSR disclosure, and such studies have mainly focused on CEO or board characteristics. For example, Lewis et al. (2014) showed that firms led by newly appointed CEOs and CEOs with Master of Business Administration (MBA) degrees were more likely to disclose information on carbon emissions than firms led by lawyers. Khan, Muttakin, and Siddiqui, (Reference Khan, Muttakin and Siddiqui2013) found that management ownership was negatively related and board independence positively related to CSR disclosure. In addition, they found that CEO duality had no effect on CSR disclosure. In extending this emergent stream of research, we take the whole of a firm's TMT into consideration. In particular, we examine a possible demographic attribute of top executives: academic experience.

CSR and CSR Disclosure in China

Economic development and growth have long been prioritized in all sectors in China. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Chinese firms were implicitly allowed to profit at the expense of environmental and social conditions. However, both the country and its firms have paid a large price for this development. For example, according to a Rand report in 2015, the policies implemented to address China's air pollution problem between 2000 and 2010 cost 6.5% of the country's gross domestic product each year (Crane & Mao, Reference Crane and Mao2015). Many Chinese firms have also incurred large losses due to corporate social irresponsibility. For example, in 2012, the drinks sold by one of the country's biggest liquor producers were found to contain plasticizers in quantities far exceeding the national standard. Plasticizers are linked to endocrine disruption, which causes reproductive and developmental disorders. The discovery resulted in an industry-wide scandal, with an estimated market value loss of nearly USD8 billion in just eight trading days (China Daily, 2012). Under such circumstances, voluntary CSR disclosure can provide valuable information to the market.

However, information is costly to produce, analyze, and report. Consequently, voluntary CSR disclosure has become a strategic issue for firms. CSR disclosure reduces information asymmetry between a firm and its stakeholders, including its investors, customers, and employees (Diamond & Verrecchia, Reference Diamond and Verrecchia1991; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Wang and Zhang2017). The information provided helps stakeholders to assess future risks facing the firm and therefore to lower the cost of capital (Cheng, Ioannou, & Serafeim, Reference Cheng, Ioannou and Serafeim2014; Verrecchia, Reference Verrecchia2001), gain insurance-like protection against environmental disasters or legal action (Godfrey, Merrill, & Hansen, Reference Godfrey, Merrill and Hansen2009; Koh et al., Reference Koh, Qian and Wang2014), and improve the firm's reputation and public voice (Lewis et al., 2014). However, when the external information environment is underdeveloped and contains a lot of information about poor firm behaviors, CSR disclosure may incur stricter scrutiny from stakeholders (e.g., activists) (Lyon & Maxwell, Reference Lyon and Maxwell2011; Marquis, Toffel, & Zhou, Reference Marquis, Toffel and Zhou2016), increased legal exposure (Cormier & Magnan, Reference Cormier and Magnan1997), and further regulatory constraints (Li, Richardson, & Thornton, Reference Li, Richardson and Thornton1997). For example, Ma, Wang, and Khanna (Reference Ma, Wang and Khanna2017) researched the Chinese infant formula industry and found that after several safety scandals, the disclosure of information on product quality had a non-positive or even significantly negative impact on consumers’ purchase decisions. In sum, we contend that voluntary CSR disclosure has become a critical issue in China, and that top executives must now address the strategic question of when to initiate voluntary CSR disclosure.

TMT: Academic Background and Professional Ethical Standards in China

All aspects of Chinese society have been reshaped by the extensive reforms that began in 1978. One of the most important reforms of this period is the privatization of state-owned sectors, allowing tens of thousands of cadres, professors in colleges and universities, and would-be entrepreneurs to move out of non-commercial occupations into private enterprises and entrepreneurship. This leap into the business world is popularly known as Xiahai, or ‘jumping into the sea’ (Dickson, Reference Dickson2007). The majority of Xiahai entrepreneurs are former teachers and professors from China's colleges and universities (Du, Reference Du1998). This tendency is so conspicuous that the slang phrase Wenren Xiahai, meaning intellectuals who dip their nets into the salty sea of avarice, has entered the Chinese vocabulary, bearing testimony to elites’ regard for the market economy. These intellectuals typically take managerial roles in big companies. Alternatively, they may form their own firms, which commonly provide access to state-managed resources or broker the resulting commercial transactions. About 40% of the publicly listed Chinese firms in our sample have top executives with academic experience.

Academic career experience differs from other demographic characteristics of top executives, such as level of education. Education reflects the development of executives’ individual knowledge and capability, whereas academic career experience is more closely related to professional discipline (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Jung, Kwak, Lee and Yoo2015). Top executives who have held the post of professor or teacher in a college or a university have at least three unique characteristics. First, due to their lengthy academic training, top executives with an academic background tend to be more rigorous than their non-academic counterparts, making them better able to process complex information. For example, Audretsch and Lehmann (Reference Audretsch and Lehmann2006) found that directors with academic backgrounds were more adept than non-academic directors at facilitating access to and promoting the absorption of external knowledge. Former academic researchers have been trained in processing and critically analyzing massive amounts of diverse information, and then integrating the insights gained to form workable conceptual models.

Second, because they are trained to think critically, top executives with academic backgrounds have a relatively good reputation for personal integrity and show a strong dedication to independent thinking. Consequently, they are less likely to be influenced by others when making decisions (Francis, Hasan, & Wu, Reference Francis, Hasan, Park and Wu2015; Jiang & Murphy, Reference Jiang and Murphy2007). They are also good communicators who can deliver information to others clearly and elicit agreement with their opinions. Communication skills honed during teaching, presenting in workshops and at conferences, and writing papers are critical in corporate settings. For example, they can facilitate the establishment of a consensus within a TMT (e.g., Combe & Carrington, Reference Combe and Carrington2015).

Third, top executives with academic backgrounds typically have higher professional and ethical standards than their non-academic counterparts. Teachers are expected to not only transmit knowledge but also assist their students in developing wisdom and trustworthiness. These characteristics are consistent with the key responsibilities and ethical standards of professors as described in the Western literature (Chickering & Gamson, Reference Chickering and Gamson1999; Tierney, Reference Tierney1997). Professors are held to even higher ethical standards in China, due to the country's longstanding Confucian culture (Chan, Reference Chan2008; Ip, Reference Ip2009; Lam, Reference Lam2003; Li & Liang, Reference Li and Liang2015). In traditional Confucian culture, teachers and professors are expected to serve as role models for personal morality. The Confucian doctrine of role transition for teachers and professors moves from ‘self-cultivation’ (becoming an ‘inner-focused sage’) to ‘regulation of the family’ (responsible for the development of one's marriage and family), to ‘bringing order to the state’ (taking care of one's country or region), and eventually to ‘preserving world peace’ (contributing to the common good or even universal harmony) (Li & Liang, Reference Li and Liang2015). To achieve this role transition or life career development, teachers and professors are commonly envisioned as possessing and seek to possess all of the cardinal virtues espoused by Confucianism, such as compassion or benevolence, ethical integrity, and a moral commitment to enhancing the welfare of others. As such, teachers and professors in China have more salient prosocial motives and higher ethical standards than individuals in other professions.

We contend that executives with academic backgrounds are well equipped to use their expertise and critical thinking skills and extend their ethical standards to their firms’ decision-making processes. They thus tend to promote higher levels of CSR disclosure than their non-academic counterparts.

TMT: Academic Background and CSR Disclosure

According to upper echelons theory (Finkelstein, Hambrick, & Cannella, Reference Finkelstein, Hambrick and Cannella2009; Hambrick & Mason, Reference Hambrick and Mason1984), the external stimuli acting on firms are so numerous, complex, and ambiguous that top executives must rely heavily on their personal attributes to determine corporate policy. They must apply their own values, preferences, and personality traits to distill and process the mass of information available from the environment, understand the reality of their strategic situation, and make strategic choices accordingly. Top executives thereby act as a prism through which information from the environment is refracted or differentially weighted within firms to form patterns that make sense to the firm's staff (Hambrick & Mason, Reference Hambrick and Mason1984; Lefebvre, Mason, & Lefebvre, Reference Lefebvre, Mason and Lefebvre1997).

Experience serves to shape people's values, beliefs, and cognitive models in ways that substantially affect their decision making and behavior (Hitt & Tyler, Reference Hitt and Tyler1991). Top executives’ professional experience is likely to influence their strategic approaches to social affairs. As previously mentioned, the academic profession has unique characteristics. Academics, such as professors in universities, are generally regarded by the public as socially responsible (Baumgarten, Reference Baumgarten1982). Baumgarten (Reference Baumgarten1982) argued that university teachers had a social obligation to help other citizens, both in and outside the classroom. Bowman (Reference Bowman2005) also argued that a teacher had to base his or her behavior on universal ethical principles, such as humility, honesty, trust, empathy, healing, community, and service. Indeed, 68% of the respondents in an ‘Image of Professions’ survey conducted by Roy Morgan Research (2016) rated university lecturing as the most ethical and honest profession.

We argue that professional and ethical standards are embedded in academic executives’ values and styles of cognition, which affect a firm's strategic choices through a three-stage filtering process. These standards first affect the TMT's field of vision (i.e., the directions in which they look and listen), selective perception (i.e., what they actually see and hear), and interpretation (i.e., how they attach meaning to what they see and hear). Specifically, compared with non-academic top executives, academic top executives possess a greater capacity to view voluntary CSR disclosure as an opportunity rather than a threat. First, academic executives are capable of dealing with the ambiguities and uncertainties related to voluntary CSR disclosure, and tend to pay less attention to the potential costs than the potential benefits of CSR disclosure because they think critically. Second, they are good at communicating with and persuading an audience due to their training in delivering clear and honest information. Consequently, academic executives tend to prioritize the benefits over the costs of voluntary CSR disclosure and view such disclosure as an opportunity to stand out in China's poor CSR context. Non-academic top executives are more likely to view CSR disclosure as a redundant, unnecessary, and costly activity.

In addition, the high professional and ethical standards conferred by an academic background drive top executives to broaden their fields of vision and incorporate more CSR activities into their firms’ behavior. These executives tend to attach more ethical meaning to voluntary CSR disclosure than non-academic executives, and selectively perceive such disclosure as a way to ensure their firms’ accountability and realize the Confucian doctrine of role transition from being an ‘inner-focused sage’ to ‘preserving world peace’ (Li & Liang, Reference Li and Liang2015). Therefore, they are likely to voluntarily disclose information on CSR activities. Non-academic top executives are likely to attach less ethical and moral meaning to CSR disclosure, and thus are less likely to engage in voluntary disclosure.

In an empirical study based on firm data from Standard and Poor's 1500 Index, Cho et al. (Reference Cho, Jung, Kwak, Lee and Yoo2015) found that firms with professor-directors on their boards received higher CSR ratings. As top executives’ personal perceptions and beliefs regarding professional ethics have a positive influence on CSR-related choices, and career experience has a strong influence on managers’ patterns of decision making (Benmelech & Frydman, Reference Benmelech and Frydman2015), we contend that firms with academic executives are more likely than firms without academic executives to take advantage of the opportunity for CSR disclosure (Lewis et al., 2014). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: Firms with top executives with academic backgrounds will be more likely to voluntarily disclose CSR activities than firms without academic top executives.

The characteristics of a TMT can only influence firm strategy if it has a relatively high degree of managerial discretion (Swanson, Reference Swanson2008). Managerial discretion exists in relatively unconstrained areas and areas in which the means of acting and the consequences of actions are highly ambiguous (Hambrick, Reference Hambrick2007). In other words, when multiple plausible alternatives exist, top executives generally have considerable freedom to choose and are therefore very likely to apply their personal values, preferences, and experiences to the decision-making process. Consequently, managerial discretion serves as the most important boundary condition for upper echelons theory. Research on CSR has also noted the role of managerial discretion. For example, Wood (Reference Wood1991) argued that managers were moral actors, and highlighted the role of managerial discretion as a driver of CSR behaviors. In addition, Swanson (Reference Swanson1999) placed managerial discretion at the top of a corporate structure determining social responsiveness and socially responsible outcomes. Discretion can emanate from several conditions, such as environmental factors (e.g., institutional pressure), organizational features (e.g., corporate governance), and individual executives’ personal qualities (e.g., tolerance for ambiguity). In this study, we focus mainly on the effects of corporate governance (e.g., firm ownership) and environmental monitoring pressure (e.g., from audit firms and analysts).

The Moderating Effect of Ownership

In the research context of China, a large proportion of firms are state-owned enterprises (SOEs). In China's transitional, centralized, socialist economic system, SOEs have a long history of taking social responsibility (Wang & Li, Reference Wang and Li2016). Even today, the government has considerable power over SOEs’ appointment of senior managers and business practices. In addition, SOEs are required to undertake social responsibility to help the government to maintain social stability and enhance social welfare. In 2008, the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission released a report entitled ‘Guidance on State-Owned Enterprises’ Social Responsibility Fulfillment’ to encourage SOEs to disclose their CSR information. Therefore, as Li and Zhang (Reference Li and Zhang2010) observed, the greater political interference experienced by SOEs compared with privately owned firms leads their top executives to make more effort to meet the government's expectations in areas such as social stability and other non-financial objectives of government policy.

Beyond the influence of the government, the legacy of China's socialist system has led to the ingrained expectation that SOEs cover all aspects of society, which continues to be ingrained in firm and managerial behavior (Kriauciunas & Kale, Reference Kriauciunas and Kale2006). Consequently, SOEs tend to have stronger or more stringent CSR norms than privately owned firms, which may serve as an informal force monitoring managerial discretion on CSR disclosure.

Academic top executives display more critical and independent thinking and have higher professional and ethical standards than their non-academic counterparts, and thus tend to self-monitor more closely. In addition, the decision on whether to disclose CSR information is made intrinsically. External monitoring and the requirement of CSR disclosure are relevant to the decision-making processes of academic top executives. An external environment that favors CSR disclosure may confirm their positive views on voluntary CSR disclosure. In summary, the academic executives of SOEs and private firms tend to show similar patterns of voluntary CSR disclosure.

In contrast, non-academic top executives are forced to positively interpret CSR disclosure by the government's demand for CSR information and the strongly held norm favoring CSR. The discretion available to non-academic executives to incorporate their personal values and preferences (i.e., less positive views on voluntary CSR disclosure) into decision making is significantly constrained. Non-academic executives in SOEs may experience greater pressure to participate in voluntary CSR disclosure than those in private firms. Therefore, state ownership serves as an additional pressure enforcing CSR disclosure, substituting for the influence of academic executives. The difference in CSR disclosure between academic executives and non-academic executives is smaller for SOEs than private firms. In the latter, academic executives still display high levels of voluntary CSR disclosure, but non-academic executives have more managerial discretion not to disclose CSR information, resulting in a larger difference in CSR disclosure between the two groups of executives. Based on these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2: The difference between the influence of academic executives and non- academic executives on voluntary CSR will be smaller for SOEs than for private firms.

The Moderating Effect of Audit Firms

The second factor affecting managerial discretion is the degree of means-ends ambiguity (Hambrick, Reference Hambrick2007). In particular, when a firm is audited by a small rather than a large audit firm, top executives have more leeway to exert their influence. Indeed, DeAngelo (Reference DeAngelo1981) documented that audit firm size affects audit quality because small audit firms tend to earn client-specific quasi-rents. Large audit firms have more skills, competence, and expertise than small audit firms. This helps them to monitor client firms and ensure transparency. They also have a stronger motivation to avoid ruining their reputation by becoming involved in clients’ accounting fraud (DeFond & Zhang, Reference DeFond and Zhang2014). Consequently, researchers have found that larger audit firms are able to more efficiently and effectively monitor manager misbehavior and better equipped to prevent firms from engaging in accounting and financial fraud (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Muttakin and Siddiqui2013; Lennox & Pittman, Reference Lennox and Pittman2010). In summary, we contend that larger audit firms have a stronger motivation to audit honestly and are better able to monitor management teams, which weakens managerial discretion to reduce transparency or even misreport information.

Whether they are audited by larger or smaller audit firms, academic top executives maintain high ethical standards and continue to view voluntary CSR disclosure as a reflection of their personal values. Audit firms do not constrain academic executives’ tendency to disclose CSR information, making the economic, social, and environmental performance of firms with these executives more transparent to the public. However, non-academic top executives are more likely to feel the monitoring effects of large audit firms. Large audit firms are likely to pay close attention to non-academic executives’ attempts to hide CSR-related information, which crowds out the executives’ discretion to incorporate their less positive views on voluntary CSR disclosure into their decision making. Small audit firms tend to place fewer constraints than large audit firms on top executives’ practices, such as specialized financial considerations. The lower levels of skill, competence, and expertise in smaller audit firms also give top executives more latitude to make the means and ends of financial decision making ambiguous. This increased discretion gives non-academic top executives who have less positive views on voluntary CSR disclosure a greater influence on decision making.

In summary, audit firms represent another force for CSR disclosure, and academic executives have a greater influence when audit firms are small rather than large. However, when firms are audited by large audit firms, those led by non-academic executives are also more likely to disclose CSR information. The difference in CSR disclosure between firms led by academic executives and those without academic executives is smaller when auditing is performed by a large rather than small audit firm. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3: The difference between the effect of academic executives and non-academic executives on voluntary CSR will be smaller in firms audited by big rather than small audit firms.

The Moderating Effect of Analyst Coverage.

Security analysts are certified industry experts who obtain private information on firms. Therefore, they are well placed to assess the implications of a firm's CSR information (Ivkovic & Jegadeesh, Reference Ivković and Jegadeesh2004; Luo, Wang, Raithel, & Zheng, Reference Luo, Wang, Raithel and Zheng2015). Security analysts can also serve as an external monitor, because they are properly trained, possess finance and accounting and industry knowledge, and are the primary audience for financial statements (Healy & Palepu, Reference Healy and Palepu2001). Indeed, researchers have found that firms manage their earnings less when they are followed by more analysts (Yu, Reference Yu2008). Irani and Oesch (Reference Irani and Oesch2013) provided strong evidence that reducing analyst coverage decreases financial reporting quality. From this perspective, the role of analysts in monitoring management teams is consistent with that of audit firms. Thus, we contend that analyst coverage is another force for CSR disclosure and tends to reduce top executives’ managerial discretion over CSR disclosure (Zhang, Tong, Su, & Cui, Reference Zhang, Tong, Su and Cui2015).

We argue that academic top executives are more intrinsically motivated than their non-academic counterparts to initiate voluntary CSR disclosure. Therefore, regardless of the level of analyst coverage, academic top executives hold higher ethical standards and evaluate voluntary CSR disclosure more positively than non-academic top executives. Consequently, firms led by academic executives tend to display a similar probability of CSR disclosure under different levels of analyst coverage. Non-academic executives hold less positive views of voluntary CSR disclosure. When analyst coverage is greater, managerial discretion is reduced and managers are subject to more pressure to undertake CSR disclosure, because analysts’ predictions have a greater influence on investor opinion and firms’ market value (Chen, Luo, Tang, & Tong, Reference Chen, Luo, Tang and Tong2015; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Tong, Su and Cui2015). Under these conditions, firms led by non-academic executives must also participate in CSR disclosure. The difference in CSR disclosure between firms led by academic executives and those without academic executives is smaller when the level of analyst coverage is higher. With less analyst coverage, top executives have more discretion, making non-academic executives more likely to influence the decision-making process to reduce the disclosure of CSR information. Therefore, the difference in CSR disclosure between firms led by academic executives and those without academic executives is greater when the degree of analyst coverage is lower. In summary, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4: The difference between the influence of academic executives and non- academic executives on voluntary CSR will be smaller for firms’ subject to more analyst coverage than firms subject to less analyst coverage.

METHODS

Research Design

To determine whether academic executives affect firms’ voluntary CSR disclosure, we apply a logit regression procedure to estimate the following model:

where CSR is an indicator variable that equals 1 if the company voluntarily issues a CSR report and 0 otherwise. The key independent variable, Academic_TMT, is an indicator variable that equals 1 if any executive in the TMT[Footnote 3] has an academic background and 0 otherwise. Executives with academic experience are those who have taught in universities or colleges, engaged in research work, and/or worked as research fellows in research institutions or associations. Based on our research hypotheses, we predict that the coefficient of Academic_TMT (β 1) in Equation (1) will be positive and significant.

We control for a set of variables that studies have found to affect CSR disclosure behavior. These control variables are as follows: a controlling shareholder indicator variable (State), which equals 1 if the company is an SOE and 0 otherwise; an audit firm indicator variable (Big_N), which equals 1 if the company is audited by a ‘Big Four’ audit firm (with ‘Big Four’ firms identified according to the market share of their audit clients’ total assets each year) and 0 otherwise; firm size (Size), the natural logarithm of total assets; leverage (Leverage), the ratio of total debt to total assets; profitability (ROA), calculated by dividing earnings before interest and taxes by total assets; growth of sales (Growth), calculated by dividing the change in sales by lagged sales; the tangible assets ratio (PPE), which is calculated by dividing total fixed assets (of property, plant, and equipment) by total assets; free cash flow (FCF), which is determined by dividing the operating cash flow by total assets; and an earnings loss indicator variable (Loss), which equals 1 if the firm reports a loss and 0 otherwise. We then add firm age (Age) and analyst coverage (Coverage, coded as 1 if the number of analysts following the focal firm is above the industry mean and 0 otherwise) to the regressions. We also include two corporate governance variables: TOP1, the percentage of ownership held by the largest shareholder; and Indep, defined as the number of independent directors divided by the total number of board directors. Other TMT characteristics are also controlled for in the regressions. Size_TMT, Age_TMT, and Tenure are the average number, age, and tenure of executive members, respectively. All of these variables are defined in Appendix A2. We also include industry and year fixed effects, and use standard errors that are robust to heteroskedasticity and clustered at the firm level in all of the regressions.

Sample and Data

Our sample period begins in 2008 and ends in 2014. We use this period because data on the executives’ academic experience before 2008 are unavailable. Our initial sample includes all Chinese A-share companies listed on the Shenzhen and Shanghai Stock Exchanges. The financial, analyst coverage, and corporate governance data are obtained from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) database. Data on the executives’ academic experience and personal characteristics are also obtained from the CSMAR database. Any missing data are manually collected by checking the managers’ résumés in the database. As our analysis is focused on voluntary disclosure, we exclude firms that are legally required to disclose CSR reports.[Footnote 4] We delete any observations for which executive team data are missing and any observations for which the controlling shareholders cannot be identified. We also exclude listed companies in the financial industry. Our final sample consists of an unbalanced panel of 13,773 firm-year observations. To mitigate the influence of outliers, we winsorize all of the continuous variables at the top and bottom 1% of their respective distributions.

Table 1 presents the sample distribution and the descriptive statistics. Panel A presents the year distribution of the sample, which shows that our observations are distributed almost evenly across the sample period. Specifically, the sample of firms that have executives with academic experience (Academic_TMT) comprises 5,785 observations, accounting for about 42% of the total sample. Panel B reports the descriptive statistics for our main variables. The mean of CSR is 0.226, suggesting that about 22.6% of the sample firms voluntarily disclose CSR reports. On average, 48.5% of the sample firms are SOEs (State), and 27.5% of the sample firms are audited by Big Four audit firms (Big_N). The mean of firm size (Size) is 21.810 (about RMB 2, 964.58 million). The mean of ownership is 35.89%, suggesting that the ownership structure is highly concentrated in our sample. Each of the TMTs comprises 15 persons on average, whose average age and tenure are 47 and 3 years, respectively. In general, the values of these variables are reasonably distributed, and the descriptive statistics are comparable with those documented in prior studies.

Table 1. Summary statistics

Panel A: Sample distribution

Notes: Table 1 presents the sample distribution and descriptive statistics. Panel A presents the year distribution of our sample. Panel B reports the descriptive statistics of our main variables. Panel C reports the univariate tests between the firms with academic experience executives and that without academic experience executives. Panel D presents the Pearson correlation matrix. Correlation coefficients in bold indicate significance at the 0.05 level or better. See Appendix for variable definitions.

EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

Baseline Results

Panel C of Table 1 reports the results of univariate tests comparing firms that have executives with academic experience with firms with non-academic executives. The means of CSR in the subsamples of firms with and without academic executives are 0.253 and 0.206, respectively; the difference is significant at the 1% level. The univariate test results show that the average CSR disclosure in the subsample of firms with academic executives is significantly higher than that in the subsample of firms without academic executives, which supports our hypotheses. Panel D of Table 1 shows the correlation matrix for the variables used in the regressions. The results show a positive correlation between Academic_TMT and CSR disclosure, which provides preliminary support for our main effect.

Table 2 reports the regression results of Equation (1), which examines the effects of academic experience on a firm's voluntary CSR disclosure. Column (1) does not include fixed effects, whereas Column (2) includes year and industry fixed effects. The coefficients of Academic_TMT are both positive and significant at the 1% level (coefficient = 0.174, t = 3.63 in Column (1); coefficient = 0.176, t = 3.58 in Column (2)), which suggests that firms are more likely to disclose CSR reports when their top executives have academic experience. The influence of executives’ academic experience on corporate CSR disclosure is also economically significant. For example, the results in Column (2) indicate that a change in Academic_TMT from 0 to 1 increases the probability of CSR disclosure by 2.46%. As the unconditional probability of CSR disclosure is 20.6%[Footnote 5], a one-standard-deviation increase in Academic_TMT increases the probability of CSR disclosure by 11.94% (2.46%/20.6%).

Table 2. Baseline and moderation models

Notes: We report in parentheses z-statistics based on standard errors that are clustered by firm and are robust to heteroskedasticity. **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; +p < 0.10; two-tailed test.

The coefficients of the control variables are generally consistent with those found in prior studies (e.g., Cho et al., Reference Cho, Jung, Kwak, Lee and Yoo2015). For instance, larger firms and more profitable firms show a higher probability of CSR disclosure. In summary, the baseline results given in Table 2 support H1: firms led by academic top executives are more likely to disclose CSR activities than those without academic top executives.

MODERATING EFFECT ANALYSIS

Ownership

Next, we test the moderating effect of firm ownership. Specifically, we test the interaction between the SOE dummy and Academic_TMT, and put the interaction term into the regression. Column (3) of Table 2 shows the results, indicating that the coefficient of the interaction term (Academic_TMT* State) is negative and significant at the 5% level (coefficient = −0.130, t = −2.10). These results support H2: the difference between the influence of academic and non-academic executives on voluntary CSR is smaller for SOEs (probability difference of 0.012) than for private firms (probability difference of 0.029).

Audit Firms

Next, we test for the moderating effect of audit firm size on the contribution of academic experience to a firm's CSR disclosure. Following Lennox (Reference Lennox2005), if an audit firm is ranked by market share (according to the total assets of the firm's annual clients) among the top four in the market, we treat that audit firm as a big audit firm; otherwise, we treat it as a small audit firm. We then test the interaction between the audit firm size dummy and Academic_TMT and put the interaction term into the regression. The results are reported in Column (4) of Table 2, which shows that the coefficient of the interaction term (Academic_TMT* Big_N) is significant in the predicted direction at the 5% level (coefficient = −0.120, t = −1.97). These results support H3: the difference between the influence of academic and non-academic executives on voluntary CSR is smaller for firms audited by big audit firms (probability difference of 0.011) than those audited by small audit firms (probability difference of 0.026).

Analyst Coverage

Next, we test the monitoring effect of analyst coverage on the relationship between academic experience and a firm's CSR disclosure. Following prior studies, we partition the firms by their year-median values of analyst coverage. We then test the interaction between the analyst coverage dummy and Academic_TMT and put the interaction term into the regression. The results are reported in Column (5) of Table 2. The coefficient of the interaction term (Academic_TMT* Coverage) is significant in the predicted direction at the 1% level (coefficient = −0.172, t = −4.41). These results support H4: the difference between the influence of academic and non-academic executives on voluntary CSR is smaller for firms’ subject to greater analyst coverage (probability difference is 0.011) than for firms subject to less analyst coverage (probability difference of 0.035).

To further illustrate the moderating effects, we plot the interaction effects in Figure 1. As shown in Figures 1(a), 1(b), and 1(c), the difference in the probability of voluntary CSR disclosure between firms led by academic executives and those without academic executives is smaller for firms that are state-owned rather than privately owned, audited by large rather than small audit firms, and subject to less analyst coverage. These results further support our hypotheses and consistently show that academic executives have a greater influence when strong forces for CSR disclosure, such as state ownership, big audit firms, and high levels of analyst coverage, are absent.

Figure 1. Interaction plots.

Endogeneity Concerns

Although the results of the previous tests cast light on the effects of executives’ academic experience on firms’ CSR disclosure, they are cross-sectional in nature and thus raise endogeneity concerns. Specifically, there can be a selection issue for firms with TMT with managerial academic experience or some omitted variables which can affect both the choice of the TMT with managerial academic experience and CSR disclosure. In this section, we address the selection of managerial academic experience in two ways: first, we apply a Heckman two-stage estimation using instrumental variables; and second, we use a propensity score matching (PSM) approach to control for the observable firm characteristics. In the next section, we use the firm fixed effect method to deal with the omitted variable issue.

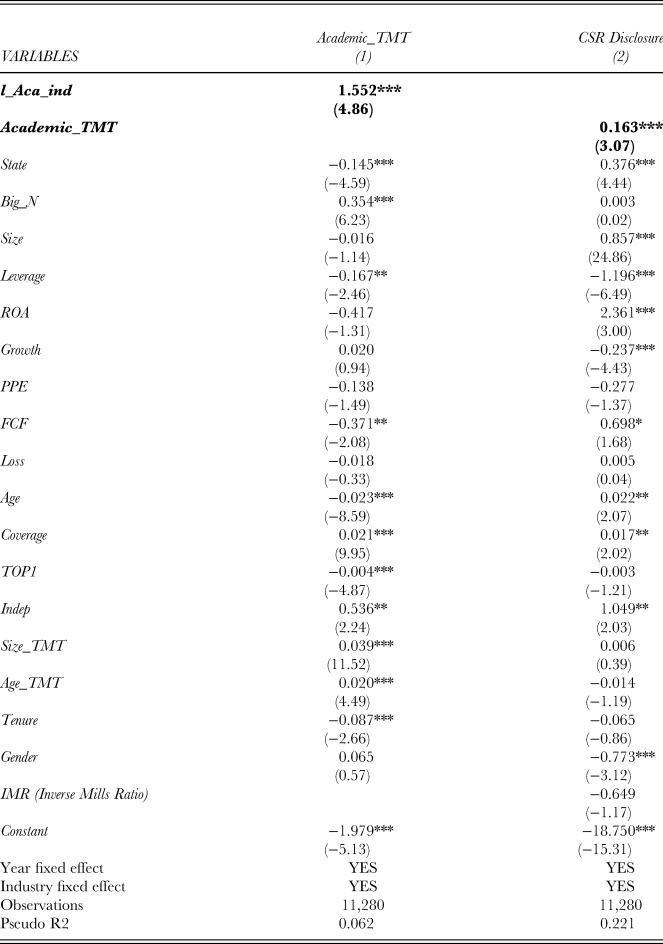

Srinidhi, Gul, and Tsui, (Reference Srinidhi, Gul and Tsui2011) found that a firm's probability of hiring a female board director was affected by whether a peer company in the same industry had hired a female director. Following Srinidhi et al. (Reference Srinidhi, Gul and Tsui2011), we use the proportion of executives with academic experience in other companies in the same industry in the previous year (l_Aca_ind) as the instrumental variable in the first-stage probit model. The assumption is that the proportion of executives with academic experience in other companies can only affect the CSR disclosure of a given firm through the firms’ appointment of a TMT with academic experience. We then add the Inverse Mills Ratio, as estimated from the first stage of the regression, to the second-stage regression equation. Table 3 reports the Heckman two-stage results.

Table 3. Heckman-two stage

Notes: Table 3 reports the Heckman two-stage results. Columns (1) and (2) show the results of the first-stage and the second-stage estimates, respectively. We use the proportion of academic experience executives in other companies within the same industry of the previous year (l_Aca_ind) as the instrumental variable in the first-stage Probit model, and add the Inverse Mills Ratio to the second-stage regression equation. We report in parentheses z-statistics based on standard errors that are clustered by firm, and are robust to heteroskedasticity. **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; +p < 0.10; two-tailed test.

Column (1) shows the results of the first-stage estimates, with a positive and significant coefficient of l_Aca_ind (1.552, t = 4.86 in Column (1)). This result indicates that the proportion of other companies that have executives with academic experience in the same industry does affect the likelihood of a firm's appointing executives with academic experience. Column (2) shows the results of the second-stage estimates. The coefficient of Academic_TMT is positive and significant at the 1% level (0.163, t = 3.07 in Column (2)), which suggests that the positive correlation between executives with academic experience and the firm's CSR disclosure still holds after considering the endogeneity problem.

We use PSM to verify that the relationship between firms that have executives with academic experience and CSR disclosure is not driven by observable firm characteristics. Following Bertrand and Mullainathan (Reference Bertrand and Schoar2003), we use PSM to construct a treatment group and a control group, and then conduct the analysis within the PSM sample. We first estimate a logistic regression using Academic_TMT as the dependent variable, and include all of the control variables used in the baseline regression of Equation (1). The logistic regression estimates the likelihood that a firm will appoint executives with academic experience. Using the predicted propensity score from this logistic regression, we then pair each treatment firm (a firm with Academic_TMT = 1) with a matched firm (another firm with Academic_TMT = 0) using the closest propensity score. This enables us to identify 5,785 matched pairs of firms to form the PSM sample.

We present the results of the PSM method in Table 4. Panel A shows the efficiency of the matching. We report the results of the logistic model for the pre- and post-match samples in Columns (1) and (2), respectively. As shown in Column (2), no significant difference in key firm characteristics is found between firms in the treatment and control groups, which suggests that the matching process is efficient. Panel B presents the results of estimating Equation (1) using the matched sample. Column (1) does not include fixed effects, whereas Column (2) includes both year and industry fixed effects. We find that the coefficients of Academic_TMT are both positive and significant at the 1% level (coefficient = 0.200, t = 3.97 in Column (1); coefficient = 0.191, t = 3.71 in Column (2)). For the control variable, the estimated coefficients are qualitatively similar with the results in Table 2. These findings confirm our previously described results regarding the endogeneity of firm characteristics.

Table 4. PSM tests

Panel A: PSM effectiveness test

Notes: Table 4 presents the results of PSM approach. Panel A shows the efficiency of the matching. Panel A shows the regression results. Panel B presents the estimation results using the matched sample. We report in parentheses z-statistics based on standard errors that are clustered by firm, and are robust to heteroskedasticity. **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; +p < 0.10; two-tailed test.

Robustness Checks

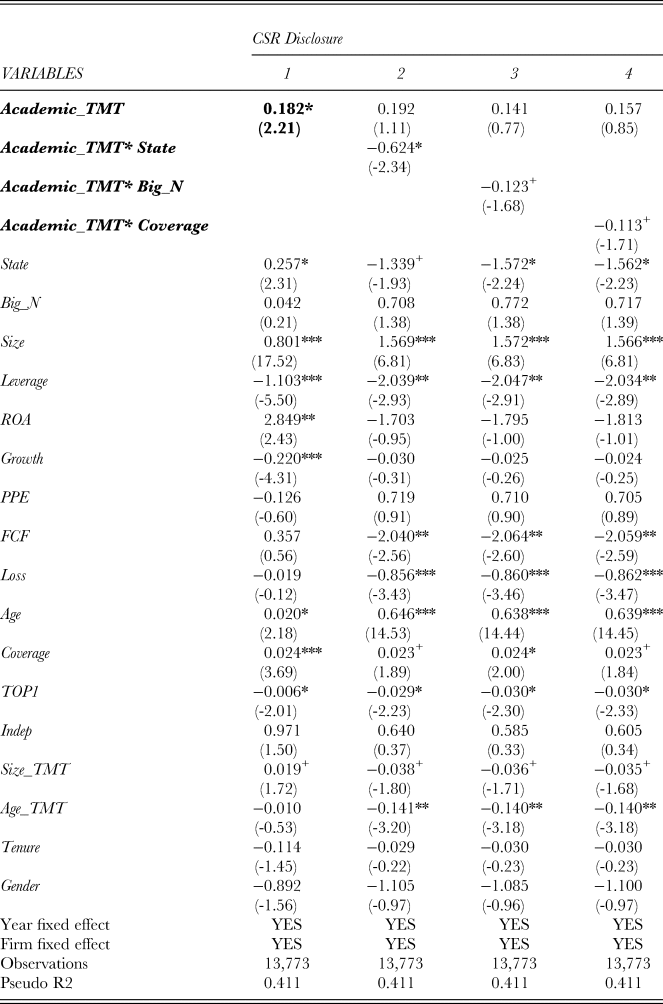

We also conduct a battery of sensitivity tests to determine whether the results are robust. First, although the baseline specification model includes a list of common determinants of firms’ CSR disclosure activities, it may omit unknown firm characteristics that are responsible for the observed results. To minimize this concern, we run firm fixed-effect regressions to control for the influence of unknown firm-level factors. We report the results of controlling firm fixed effects in Table 5. The results are consistent with those obtained using the baseline specification model shown in Table 2. In particular, the coefficient of Academic_TMT is significantly and positively related to CSR at the 5% level (0.182, t = 2.21 in Column (1)). For the economically magnitude, similar with Table 2, the results in Column (1) indicates that a one-standard-deviation increase in Academic_TMT increases the probability of CSR disclosure by 12.28%. For the moderation results in Columns (2) to (4), the interaction terms are all significantly negative in the prediction direction (-0.624, t = −2.34 in Column (2); -0.123, t = −1.68 in Column (3); -0.113, t = −1.71 in Column (4)). The results in Table 5 suggest that the baseline regression results in Table 2 are not affected by serious omitted firm-level factors. In addition, compared with the year fixed effect and industry fixed effect models (Models 2–5 in Table 2), when we included firm fixed effects into the models (Models 1–4 in Table 5), the variance explained (i.e., R2) increased from 0.22 to 0.41, indicating that our models have captured a large amount of variance for the data. We also examine the effect of one year lagged academic experience on CSR disclosure to mitigate concerns about reverse causality. The untabulated results show that our results still hold. In addition, we also run the reverse model in which CSR disclosure predicts academic TMT. The results show that CSR disclosure has no significant effect on managerial academic experience (β = 0.006, t = 0.51, R2 = 0.035), further mitigating the concerns of reverse causality.

Table 5. Robustness check: firm-fixed effects

Notes: Table 5 presents the results of firm fixed effect. We report in parentheses z-statistics based on standard errors that are clustered by firm, and are robust to heteroskedasticity. **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; +p < 0.10; two-tailed test.

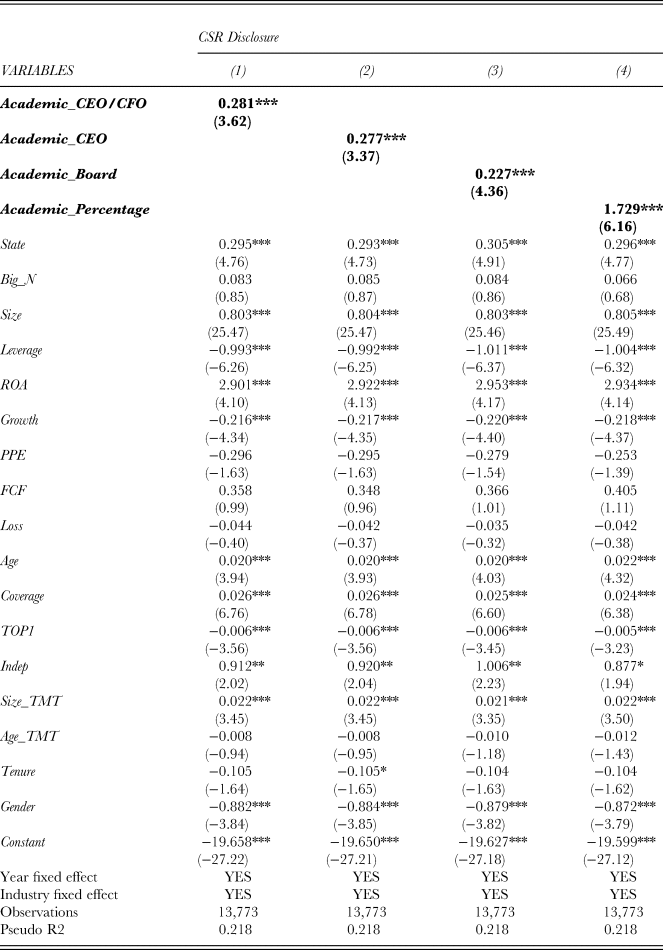

Second, we use the following alternative definitions of ‘top executives’: (1) the CEO and chief financial officer (CFO), (2) the CEO only, (3) the set of executives who are also on the board of directors, and (4) the percentage of executives in the TMT with academic experience. Table 6 reports the regression results using these three alternative definitions of firm executives with academic experience. The coefficients of Academic_CEO/CFO, Academic_CEO, Academic_board, and Academic_Percentage are all positive and significant at the 1% level (0.281, t = 3.62 in Column (1); 0.277, t = 3.37 in Column (2); 0.227, t = 4.36 in Column (3); and 1.729, t = 6.16 in Column (4)). The results shown in Table 6 indicate that our main conclusions are not affected by differences in the definition of firms’ executives. We obtain similar results when one-year-ahead disclosure is used to address the potential timeline problem.

Table 6. Robustness check: Alternative academic executives measures

Notes: Table 6 reports the regression results using alternative executives with academic experience measures. Specifically, we redefine the executives by the following definitions: (1) CEO and CFO; (2) CEO; (3) executives who are dually on the board of directors; and (4) the percentage of executives with academic experience in the team. The moderation effects were robust across the four types of measures. To save space, we did not report the moderation results. Details are available upon request. We report in parentheses z-statistics based on standard errors that are clustered by firm, and are robust to heteroskedasticity. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; two-tailed test.

Finally, we control for the executives’ educational background in our regression estimate model. Following Bamber, Jiang, and Wang, (Reference Bamber, Jiang and Wang2010), we construct an education background indicator variable (Education_TMT), defined as the average level of the educational degrees held by the TMT members. Specifically, we code a Ph.D. (including an honorary doctorate) as 5, a Master's degree (including an MBA) as 4, a Bachelor's degree as 3, a college degree as 2, and a technical secondary certificate or below as 1. Our results still hold after controlling for the executives’ educational backgrounds. All of the results are available upon request.

DISCUSSION

A substantial body of research has been conducted on CSR activities and CSR performance. The results of this stream of research show that firms operate in a nexus of stakeholders and seek to guarantee their legitimacy in the eyes of stakeholders through CSR activities. CSR disclosure is an important yet underexplored topic. In addition, ‘the conceptual determinants of [CSR] … remain relatively under-developed’ (Brammer & Millington, Reference Brammer and Millington2008: 1326). Although institutional and stakeholder theory have enlarged our understanding in this stream of research, the literature has paid limited attention to top executives’ intrinsic values and preferences regarding social issues. It has also failed to explore the reasons why different firms form different strategic postures and engage in different degrees of voluntary CSR disclosure.

In this study, we draw on upper echelons theory to propose that a TMT's characteristics (specifically academic background) influence its firm's strategic stance on social issues, and thus have specific effects on voluntary CSR disclosure. Based on a sample of listed firms in China, we find strong evidence that firms led by academic top executives are more likely than those without academic executives to voluntarily issue CSR reports on their economic, social, and environmental performance. State ownership, audit firm size, and analyst coverage are found to moderate the main relationship. These findings contribute to the literature in several ways.

First, we address the puzzle of why firms subject to similar external pressures from their stakeholders make different choices regarding CSR activities, such as CSR disclosure. Studies have examined the influence of various organizational characteristics, such as firm ownership, external pressure, and industry risk, on a firm's CSR behaviors (Delmas & Toffel, Reference Delmas and Toffel2008; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Wang and Zhang2017; Marquis & Qian, Reference Marquis and Qian2014; Reid & Toffel, Reference Reid and Toffel2009). However, we demonstrate that a firm's CSR behaviors can also be explained by the characteristics of its TMT. Thus, by offering new insights into the relationship between managerial characteristics and CSR disclosure, we extend the scope of prior literature from mandatory to voluntary CSR disclosure and highlight the importance of TMT career experience.

Second, by examining the effects on firms’ behaviors of academic background, a little-investigated aspect of top executives’ career experience, we follow the recent trend of focusing on the characteristics of top executives and contribute to understanding of the role of managers in firms’ strategy making (Hambrick, Reference Hambrick2007). The literature has examined executives’ career experience in terms of military service (Benmelech & Frydman, Reference Benmelech and Frydman2015; Malmendier, Tate, & Yan, Reference Malmendier, Tate and Yan2011), education (Lewis et al., 2014), career variety (Crossland, Zyung, Hiller, & Hambrick, Reference Crossland, Zyung, Hiller and Hambrick2014; Custódio, Ferreira, & Matos, Reference Custódio, Ferreira and Matos2013), and early-life experiences of disaster (Bernile, Bhagwat, & Rau, Reference Bernile, Bhagwat and Rau2017). Our study shows that academic background deserves more attention in future research. Given the prevalence of firms led by academic top executives in China and the unique characteristics of the academic profession, it is practically relevant and worthwhile to investigate whether academic TMT members have a predictable influence on firms’ strategies and their outcomes in China.

Third, the finding that academic executives behave consistently regarding CSR voluntary disclosure, irrespective of boundary conditions such as ownership, audit firm size, and analyst coverage, may contribute to the corporate governance literature by offering an alternative method of mitigating a firm's socially irresponsible activities. Similarly, Cho et al. (Reference Cho, Jung, Kwak, Lee and Yoo2015) found that firms with professor-directors on their boards received higher CSR ratings. We further demonstrate that TMT executives with professorships improve CSR disclosure and that their tendency to maintain a high level of CSR disclosure is not affected by external monitoring. This finding strongly supports Li and Liang's (Reference Li and Liang2015) argument that as their careers develop, academic TMT executives tend to have stronger prosocial motives and engage in more prosocial behaviors to realize their expected role transition. These behaviors are intrinsically motivated and not easily affected by external forces. Future research may gain more insight by examining the governance effect of academic TMT composition and its potential to reduce firms’ agency problems.

Finally, we specify the external contingencies that limit managerial discretion, supporting a branch of upper echelons theory and previous research on the monitoring effects of audit firms and analysts. For example, the results of our analysis clearly show that the moderating effect of state ownership may not be as negative as the literature has assumed. Researchers have tended to equate state ownership with lower efficiency and reduced managerial incentives (e.g., Ramamurti, Reference Ramamurti2000; Zhou, Gao, & Zhao, Reference Zhou, Gao and Zhao2017). However, we show that state ownership can foster a strong tendency to favor CSR, and thus effectively constrain non-academic executives’ tendency to suppress CSR disclosure. Future research should extend these findings to other relationships to examine the robustness of state ownership as a tool for constraining managerial discretion. In terms of the moderating effects of audit firm size and analyst coverage, we provide more empirical evidence in the CSR context that audit firms and analysts serve as external monitors for managers (e.g., Healy & Palepu, Reference Healy and Palepu2001; Lennox & Pittman, Reference Lennox and Pittman2010; Yu, Reference Yu2008). They thus offer an effective means of constraining non-academic executives’ attempts to avoid CSR disclosure.

Our study also has implications for business practice. We show that senior managers do affect a firm's disclosure of CSR. People with higher ethical standards and a stronger spirit of service, such as university professors, are more likely to make CSR information publicly available. To promote social responsibility, we thus suggest that firms reconfigure their TMTs to incorporate members with an academic background, such as university professors. If firms lack academic executives, they should consider making other arrangements to safeguard their social responsibility, such as hiring large audit firms. In terms of public relationships, we recommend that the role of information intermediaries, such as analysts, be enhanced to more effectively monitor the behaviors of firms and their managers. This would limit the agency of managers who hold less socially responsible views, values, and preferences and thus increase the possibility of firms’ engaging in socially responsible activities, such as voluntary CSR disclosure. Such safeguards are especially important in China and other developing economies. As China moves toward a market-based economic system, the importance of state ownership as a force for CSR disclosure is decreasing, and although market forces such as auditing players and information intermediaries are still developing, they are becoming weaker; therefore, firms need another force to ensure that they remain socially responsible. Our study demonstrates that academic executives provide a critical candidate to fill the vacuum in governance mechanisms during this transition.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Like any other empirical study, ours has a number of limitations that provide opportunities for future research. First, our sample consists of companies listed in Chinese stock markets. Therefore, as institutional contexts and market environments differ between countries, the generalizability of our findings is to some extent limited. Future studies could re-examine our arguments in various countries to extend our findings. For example, researchers could examine country-specific factors such as national culture to capture cross-country effects. In addition, although the quality of CSR reports varies greatly, in this study we test only the relationship between TMT members with academic experience and voluntary CSR reporting. We do not seek to determine whether firms whose TMT members have academic experience also issue higher-quality CSR reports. Finally, archival data are the sole source of the study's quantitative empirical findings. We thus fail to investigate the processes or mechanisms by which TMT members with academic experience may promote firm CSR disclosure. In the future, scholars could pursue more qualitative exploration to gain insight into how TMT members with academic experience influence management teams to engage more fully in socially responsible practices.

APPENDIX I. A Review of Representative Studies on CSR in the Literature

APPENDIX II. Variable Definitions