Introduction

In October 2016, during a seminar at one of the universities in Almaty, students actively discussed the potential influence of the world order upon Kazakhstan. While examining the model of Kazakhstani national development, the lecturer shifted the focus of discussion to consider the enormous differences that exist between the north and the rest of the country, with the former being dominated entirely by the Russian language, culture, and mentality. As an example, the lecturer brought up an anecdotal story of an elderly Russian-speaking woman, an inhabitant of today’s Öskemen and former Ust’ Kamenogorsk, who wrote a letter of complaint to the president about the poor condition of the roads in that area. When asked which president she had written to, the old lady, according to the lecturer, proudly replied: “of course to the president of our country—Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin.” The students, in turn, appeared to be perplexed by the inability of the person to comprehend which country she lived in and where she truly belonged. In the same vein as the lecturer, the analyst from the Kazakhstani foundation “Civil Society,” Viktor Kovtunovskii, talks about the persistent desire among the Russian-speaking citizens of Kazakhstan to live in a bigger Russian state (Kalishevskii Reference Kalishevskii2014). The idea, however, that the territory of Kazakhstan, stretching from Oral to Öskemen along the border with the Russian Federation, is heavily Russified was voiced not only by several Kazakh academics and politicians. Russia’s intelligentsia has also often framed the territory of the north of Kazakhstan as inherently Russian lands. For example, the prominent Russian nationalist Aleksandr Solzhenistyn in one of his books openly disputed the “artificial” borders between Russia and northern Kazakhstan, and insisted on incorporating a historically defined “Russian zone” in the Russian Federation (Solzhenitsyn Reference Solzhenitsyn1995). In light of the crisis in Ukraine, another Russian politician, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, called upon Kazakhstan to join Russia as the “Central Asian Federal Region” (tengrinews 2014).

In general, Kazakhstan, which in 1991 gained its independence from the Soviet Union, represents an interesting case for the scholarly examination of a country’s various efforts at solving a “national situation,” marked by the co-existence of numerous ethnic groups on its territory. As a result of the Soviet national and economic development policies, by the time the Soviet Union collapsed, Kazakhstan was the only independent state where the titular nationality represented a minority, with Russians alone constituting 37.8% of the entire population (Peyrouse Reference Peyrouse2007, 482). The distinct “national situation,” however, did not arise only from demographics, but also from the geographical distribution of ethnic groups. While southern areas are predominantly populated by ethnic Kazakhs, the northern and the north-eastern regions are home to other ethnic groups like Russians and heavily Russified Ukrainians, Germans, and Poles. Such geographical concentration of Russian speakers along with several irredentist claims on parts of the country’s territory generated concerns about the territorial integrity of the newly independent state (Commercio Reference Commercio2004; Diener Reference Diener2016; Wolfel Reference Wolfel2002). The avoidance of potential conflicts and the formation of a unified nation out of its polyethnic and polyconfessional population represents, therefore, the major challenges for post-Soviet Kazakhstan (Kadyrzhanov Reference Kadyrzhanov2014, 8). Seeking to reconcile civic, ethnic, and transnational dynamics of national identity formation, Kazakhstan’s government balances out between transnational “Eurasian” cultural identity and a “Kazakhstani” civic identity, while simultaneously promoting the Kazakh ethno-nation (Diener Reference Diener2016, 132). According to outside observers and politicians mentioned above, despite such a multipronged identity project that promotes multinational country-based patriotism, people in the north-eastern regions of Kazakhstan still hold on to their Russianness, while resisting Kazakhness or, by the same token, transnationalism.

Amidst such discussion, what does Russianness and Kazakhness mean for specific individuals inhabiting this region? How are antagonistic national politics of Russia and Kazakhstan, but also the effects of the forces of capitalist globalization, reflected on a local level? How do Russian speakersFootnote 1 there feel in relation to the place they inhabit within a particular socio-political context? How do they negotiate between different national identity projects in their everyday lives? To answer these questions, I lived in Petropavlovsk from August until November 2016, a city of 217,205 people (Passport of North Kazakhstan Region 2016), which contains a large number of Russian and Russian-speaking population (roughly 70%). In this article, I draw on that experience to reflect on the ways Russian speakers make sense of the place they live. I study how ordinary people appropriate spaces though different symbolic practices to construct their sense of belonging and to negotiate their complex individual position between local and national, between Russian, Kazakh, and the often-neglected “global” aspect in their lives.

Following the “spatial turn” in anthropology, the concept of “place” has been increasingly brought to the fore as a constitutive dimension of social life (Lawrence and Low 1990). It refers to a physical location, both imagined and real, a product of interrelations representing a continuum of global to intimate interactions (Sen and Silverman Reference Sen and Silverman2014). Anthropologists have, furthermore, argued that “place” is essential for not only social organization and political processes, but also for social relations and personhood. When studying how places are produced and constructed, the researchers, however, far too often focused on the more obvious and the official, that is the national and the state level (for a critique see Edensor Reference Edensor2002). The abrupt socio-political reconfigurations in the countries of the former Soviet Union have prompted a lot of academic research into the elite schemes for ruling and transforming space and society (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996; Diener Reference Diener2016; Kolstø Reference Kolstø1998). In the context of Kazakhstan, special attention has been dedicated to the state- and nation-building strategies of the government (Cummings Reference Cummings2005, Reference Cummings2010; Schatz Reference Schatz2004).

Although within post-Soviet research there are several studies that go beyond the elite projects and explore the ways Russian speakers interact with places they inhabit, such studies not only draw conclusions about aggregate national or regional populations, but also remain fixated on the notion of territoriality bound solely to a national level (disregarding the idea that identification with places can be played on multiple scales) (for example, Barrington et al. Reference Barrington, Herron and Silver2003; Nimmerfeldt Reference Nimmerfeldt2011). However, following Edensor (Reference Edensor2002, 17), people’s sense of belonging and a meaningful relationship with the environment are not only displayed through official cultural assertions, but are also grounded in the “mundane details of social interaction, habits, routines and practical knowledge” (Edensor Reference Edensor2002, 17). According to Ryden (Reference Ryden1993, 37–38), place is based on symbolic meaning “which people assign to that landscape through the process of living in it.” The importance of focusing on everyday life in particular localities is also noted by Tanya Richardson in her ethnographic study of Odesan’s sense of place and their attempts to produce and re-produce Odesa as a distinct locality through the narration of histories (Richardson Reference Richardson2008).

It becomes clear that places are not only constructed from above, or, in Lefebvre’s sense, produced by structural forces such as the state. Rather places are also socially constructed and communicated daily through symbolic forms and practices (Low 2000, 127–128). There is, therefore, the need for more ethnographic studies that move beyond the exploration of the top-down projects aiming to transform state and society, to study how ordinary people experience places they inhabit and how they themselves negotiate their complex position within those states. While acknowledging the role of the state and country’s elites in producing space “from above,” this article is a contribution to the growing body of literature that seeks to approach the notions of place and belonging from the less visible everyday scale (Bissenova Reference Bissenova2017; Laszczkowski Reference Laszczkowski2016; Seliverstova Reference Seliverstova2017). Similarly to Bhavna Dave (Reference Dave2007), who has thoroughly examined the construction of nationhood in Kazakhstan, it challenges the understanding that the local population is a passive recipient of different national projects enacted by the elites and demonstrates how the meanings behind Russianness and Kazakhness are constitutive of daily practices in place among various individuals and groups.

In this article, the empirical material stems from 24 interview narratives collected in the Russian language.Footnote 2 To complement the data, this work relies also on a dozen unrecorded unofficial talks that took place particularly during walking tours or in the households of my collaborators, where I was often invited as a guest. The bulk of the knowledge of a local life, thus, largely derives from the ethnographic practices of “deep hanging out” (Geertz Reference Geertz, Clifford1998) with my participants: sharing with them the experiences of various places by strolling through the city, going shopping, visiting their homes, and having numerous conversations about life in Petropavlovsk. During walking tours and home visits I paid particular attention to symbolic practices such as language, food consumption, and certain familial traditions as well as the daily routines of my participants.

This study reveals the different ways Russian speakers interact with the socio-spatial environment around them, as well as imagine and perform their lives in Petropavlovsk. All conceptualizations of place and understandings behind the meanings of Russianness and Kazakhness stem directly from my collaborators. In the first strand, the city is framed as a “Russian-speaking space,” which is linked to the narratives of common Russian language, history, and specific mentality that connect people residing in the area. These personal narratives further intersect with antagonistic national narratives projected upon Russian speakers from both states—Russia and Kazakhstan. The second strand presented in this article uncovers the often invisible Kazakhness in the habits and everyday practices of the local population and argues that Russian speakers often adopt certain “Kazakh” ways of life in their mundane performances. The third strand goes beyond the simple binary to represent day-to-day Petropavlovsk as a “global” space, through which a link with the rest of the world is established. In particular, I examine how the forces of capitalist globalization and changes in economic and technological conditions are experienced by Russian speakers daily and how such forces feed into the creation of new cultural forms that transcend the typical “entrenched” divisions between Russianness and Kazakhness. All in all, the findings of this study challenge the much-cited research by David Laitin (Reference Laitin1998), who proposed the emergence of a conglomerate identity category among Russian speakers—“Russian-speaking nationality” – as an alternative to assimilation with the titular population or to mobilization as Russians (1998, 263). Instead it demonstrates how local, national, and global identities of people are mutually entangled and constitutive, as well as dynamically negotiated with relation to place and performance.

The “Northern Gates of Kazakhstan”

According to the geographers Newman and Paasi (Reference Newman and Paasi1998), borderlands are particularly suitable sites for analyzing the ambivalences in people’s construction of self and place. In the borderland areas, the local population often feels pushed away from the national center and is, instead, pulled toward the borderland inhabitants on the other side of the geographical boundary (Donnan and Wilson Reference Donnan and Wilson2001, 53). In this sense, according to Cheskin and Kachuyevski (Reference Cheskin and Kachuyevski2018) people on both sides of the geographical border may share “common cultural identity traits, which conflict with traditional views of the convergence of state and nation.”

The physical proximity of Petropavlovsk to the Russian border explains the significance of examining the relationship between people and their understanding of place in this particular town. Founded in 1752 by Tsarist Russia during the expansion of Russian settlement, Petropavlovsk was initially a part of a string of forts stretching across southern Siberia. The city was intended to defend the newly conquered territories of the Russian Empire and to facilitate trade with the local Kazakh and other Central Asian tribes. After the fall of the empire, Petropavlovsk was in 1925 included into the newly-established Kazakh Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic, which in 1936 was detached from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and made the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic (KSSR), a union republic within the Soviet Union (Ubiria Reference Ubiria2015, 124).

Throughout the Soviet period the city grew due to resettlement policies, Stalin’s deportations in the 1930s and 1940s, and the development of the virgin lands under Khrushchev. The forms and reasons for the movement of people were numerous and migration varied from being voluntary to being forced, from movements of the entire “nations in the echelons” to a movement of a single person in search for a better life (Shukurov and Shukurov Reference Shukurov and Rustam1999, 202). During the Virgin Lands Campaign alone, around two million mainly Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian “volunteers” surged to the territory of today’s Kazakhstan, considerably diluting the ethnic Kazakh population (Peyrouse Reference Peyrouse2008a, 2). Apart from the representatives of the aforementioned Slavic nations, a substantial number of other groups have found themselves on foreign territory—Germans, Tatars, Armenians. Being separated from their original homelands, these typically non-Russian people preferred to join the dominant Russian culture and language, which served as a lingua franca throughout the whole Soviet Union. Upon the collapse of the Soviet Union the majority of the Russian and Russian-speaking population was spread around the north and the northeast of Kazakhstan. Despite considerable outmigration to other countries, predominantly to Russia, the borderland cities like Petropavlovsk are still home to more than 50% of Russian speakers with ethnic Kazakhs constituting a minority there.

Nowadays Petropavlovsk, which is located close to Russia’s border, is commonly referred to as the “northern gates of Kazakhstan.” The region is characterized by significant cross-border interactions on both state and local levels. For example, the station along with the whole railway infrastructure in Petropavlovsk is still leased by the South Ural railway of Russia. Despite such cross-border activity and economic cooperation, it is rather difficult to speak of socio-political and cultural deterritorialization of the borderland. In fact, since Kazakhstan has gained its independence, the government has been relentlessly seeking to nationalize its periphery and to dilute the dominance of the Russian culture and language in the region by renaming the streets in the Kazakh manner.Footnote 3 The policy of linguistic and ethnic Kazakhization has been noticeable also in other fields: formalization of the Kazakh language, the decline of Russian in employment, along with the deterioration of education for the Russian-speaking students (Peyrouse Reference Peyrouse2007, 485). In turn, Russian speakers regarded such policies as discriminatory and expressed a feeling of unequal treatment by the state based on their ethnicity (Abdigaliev Reference Abdigaliev1995, 140).

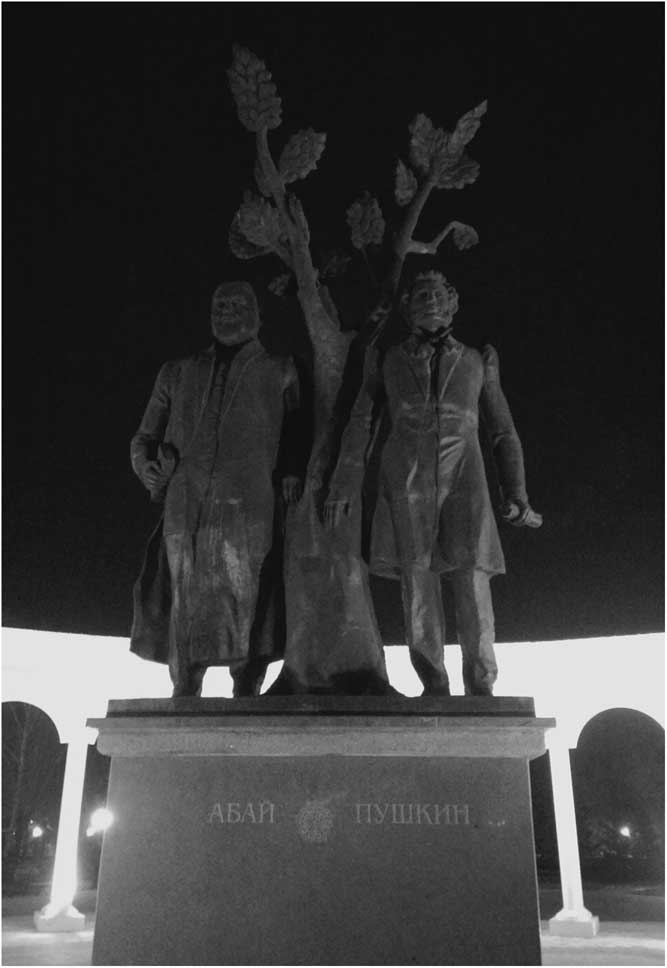

At the same time, however, a lot of effort is invested into constructing Petropavlovsk as a multicultural city. One such example is the erection of the monument in 2006 dedicated to two poets: Kazakh – Abay Qunanbayuli, and Russian – Aleksandr Pushkin. Two poets, representing different countries, cultures, and times, stand side by side to symbolize the friendship of people in the city and country in general (Figure 1). The different ways of constructing the city as Kazakh, on the one hand, and multicultural, on the other, arguably feeds back to Kazakhstan’s overall efforts to perpetually negotiate between ethnic and civic elements in its state- and nation-building processes and to combine jus sanguinis and jus soli (Diener Reference Diener2016, 134).

Figure 1 Pushkin and Abay monument. Source: Author’s photo, April 2015.

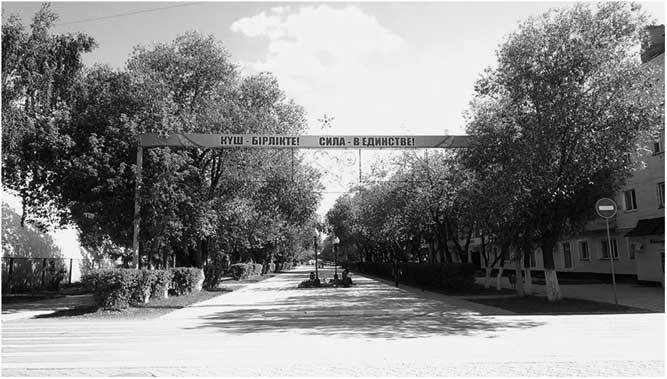

The necessity to promote a civic-based patriotism and to exhibit publicly the unity between people seems to have only grown, especially in light of the crisis in Ukraine. Politically and geographically speaking, Petropavlovsk, with its large number of Russian speakers, has been perceived as a potential security threat for the Kazakhstani nation-state. This is predominantly due to a belief that most of the population in northern Kazakhstan still looks toward Russia rather than toward its own country, as the story in the introduction revealed. At the same time, some politicians and thinkers from Russia’s side too have questioned the statehood of Kazakhstan, which was perceived as a warning by the latter (Kalikulov Reference Kalikulov2014). The fears of potentially disloyal citizens residing in the cities along the border with Russia have recently grown exponentially, leading to more proactive reactions at the Kazakhstani top governmental level. For example, to foster tolerance in the country and to prevent potential inter-ethnic clashes patriotic slogans by President Nursultan Nazarbayev were put up at the center of Petropavlovsk (Figure 2).

Figure 2 “Unity is power.” Slogan at the main pedestrian street, Konstitutsia, in, Petropavlovsk. Source: Author’s photo, August 2016.

The content that the Kazakh elites try to transmit via the use of public space is certainly important, as is important the discourse emanating from Russia, which arguably attempts to revitalize the links to its so-called Russian-speaking diaspora abroad.Footnote 4 While bearing in mind the structuring impact of the state and other external forces, it is vital to emphasize how places are continuously constituted and constructed as meaningful realities by people themselves. In the end, place is not merely an environment that exists independently of those who experience it. Rather it is lived by people and shaped by their activities and perceptions (Lyytikäinen and Saarikangas Reference Lyytikäinen and Saarikangas2013, ix). Seeking to describe our experiences of place, David Seamon (Reference Seamon1980) has introduced the concept of “time-space routines,” suggesting that places are performed daily through people living their everyday life. It is, according to him, through participating in these daily performances, though repeated bodily movement, language, narratives, and symbolization that we form a feeling of belonging to a place and thus become insiders of those places. In a similar vein, Paul Connerton (Reference Connerton1989) wrote about the concept of “habit memory” which emphasizes the difference between thinking of an urban “artefact” and living the same urban “artefact.” In other words, Petropavlovsk as perceived by outside observers, for instance the policy-makers or the lecturer mentioned in the introduction, will considerably differ from the experiences of those who “live” place and have appropriated it as one’s own.

The way the targeted groups negotiate their individual complex position between local and national but also the global thus has multiple possibilities and is “multivocal” (Rodman Reference Rodman1992). How Russian speakers reconstruct Petropavlovsk, live and perform their daily lives there as well as what habits, traditions, and preferences they have, is the focus of the rest of this article.

Petropavlovsk as a “Russian-speaking Space”

Strolling through the streets of Petropavlovsk and looking at the way the city is adorned—traditional Kazakh ornaments, predominantly blue and yellow colors from the national flag, visible on fences and flowerpots—leaves a clear impression that we are in Kazakhstan. Exploring further, one notices that all advertisements and names are written in two languages, all bus stops are first announced in Kazakh followed by the Russian version. The singing fountains at the main pedestrian street Konstitutsia are also accompanied by Russian and Kazakh songs, as well as by those from old Soviet films. In addition, at national public celebrations and concerts organized by the state, one can observe different ethnic groups representing their traditional music or dances to the audience. Petropavlovsk now seems multicultural.

Yet the people I spoke to in Petropavlovsk describe the city rather as a “Russian-speaking space.” Artem, a freelance photographer and a student in his thirties, whom I met by chance in a park, seemed to struggle to envision Petropavlovsk as a part of Kazakhstan:

A: Somehow, I usually forget that I live in Kazakhstan.

I: How come, where do you live then?

A: Well, in some kind of, I don’t know…In some kind of Russian-speaking space, I would say. I sort of understand, that it’s not Russia here, but Kazakhstan. But Russia is somehow more in my consciousness, Russian culture, Russian language, Russian people. Therefore, I somehow forget about it. (Artem, 30, from a personal interview in August 2016)

By invoking language and certain inherent Russian cultural traits, Artem here reconstructs his place of residence as Russian, as distant from Kazakh. The way he describes Petropavlovsk or his vision of it seems to be akin to the concept of Russkii Mir (Russian World), actively promoted by the Kremlin. Established in 2007 by the Russian authorities, the Russkii Mir Foundation seeks to popularize the Russian language and culture as a “crucial element of world civilization” (Cwiek-Karpowicz Reference Cwiek-Karpowicz2012). The top-down discourses furthermore place Russia at the core of this Russkii Mir, as a homeland to all those Russian speakers abroad. Importantly, while Artem expressed affection for Russian culture, his emotional and cultural ties did not seem to be necessarily associated with Russia as a country per se, but with an imaginary concept. The line was somehow drawn between the Russian Federation and the larger Russian world that transcends physical borders. It was the “Russian environment” that Artem was drawn to, not the country.

As it crystallized during further conversations with other research collaborators, the shared Russian language, traditions, and history, indeed help to strengthen cultural affinity with Petropavlovsk as a Russian-speaking space. Language especially was regarded as a vital and intimate dimension of belonging to a place and community, conceptualized not only as the ability to understand the words other people utter, but also the deep meaning behind them. The significance of language in the formation of person-place relations has been highlighted by numerous researchers across a range of disciplines (Di Masso, Dixon and Durrheim Reference Di Masso, Dixon and Durrheim2014; Low Reference Low1992). Such an approach treats the day-to-day linguistic practices as a process that actively creates both our lived experiences and the meanings we attribute to different places. Indeed, Roman, who works as an IT-specialist in one of the Internet companies, has described Petropavlovsk as a Russian city precisely due to the Russian language that dominates the everyday lives of people:

So, I consider, at least in the near future, Petropavlovsk to be a Russian city…Here you can easily speak Russian, and no one will look at you askance, unlike, for example, how it can be in the southern regions of Kazakhstan, as I was told. But I have a feeling that the local authorities are systematically trying to change it. For example, they rename the streets and other objects into Kazakh, provide quotas at a university for southerners, thus taking away the scholarships from the locals. The local population endures so many things. They show their resentment briefly online and that’s it. The local government does not consider our opinion. Perhaps, the only thing that the local population won’t allow to do is to rename the city, for example, into some Kyzyl Zhar. The city was named in honor of St. Peter and Paul. Yes, so far Petropavlovsk is a Russian city for me. Will it ever cease to be such? Probably, but for this, numerous years must pass. (Roman, 30, from a personal interview in September 2016)

In June 2011, President Nursultan Nazarbayev signed a state program for the development and functioning of languages in the country, seeking to “create a harmonious language policy and to ensure the full functioning of the state language as the most important factor in strengthening the national unity while preserving the languages of all ethnic groups” (Prime Minister of Kazakhstan, 2011). According to the program, 80% by 2017 and 95% by 2020 of the Kazakhstani adult population should be able to speak the Kazakh language. Despite the state attempts to bring more Kazakh into public spaces, Petropavlovsk remains dominated by the Russian language in the daily lives of its inhabitants. As the leader of the NGO “Last Hope,”Footnote 5 Ruslan Asaubaev, stressed, apart from the limited opportunities to practice Kazakh in northern Kazakhstan, there is also a poor distribution of the state fiscal resources dedicated to the acquisition of language proficiency, poor teaching methods used in schools and universities, outdated textbooks, and the lack of prestige of Kazakh in general. Bearing this in mind, a sense of resentment to the so-called Kazakhization, that is clearly noticeable in Roman’s words is therefore less surprising. The Kazakh language remains foreign to Roman and even sounds unpleasant “as if something is cutting through the ears.”

Overall, there seems to be a general discomfort with the attempts of the state to bring more Kazakhness into the city. When asking Artem why he sometimes feels uncomfortable in Petropavlovsk, he replied:

Well, there are moments, although I haven’t really experienced them much…well, but I also heard of them. There is for example foreign speech, well, other language. For example, you receive a text message from your provider in a different language or you see an advertisement only in one foreign language. It seems to be nonsense, I don’t even need this ad, but… (Artem, 30, from a personal interview in August 2016)

In a similar vein, Lyudmilla, a woman in her late twenties, who at the time of our conversation was on maternity leave, distanced herself from the Kazakh culture and expressed concern for the future of her child:

You know, we live in a country, where the Muslim society with different traditions dominates. So the language, I mean, I know that my child won’t be able to speak Kazakh. She won’t be able to understand it well at school and get a decent education. To get a good job here or anywhere in Kazakhstan, for example somewhere in the government, will be simply impossible. (Lyudmilla, 27, from a personal interview in September 2016)

The fear that the growing visibility of Kazakhness in the cityscape could diminish the significance of Russian frames certain responses to the urban landscapes in Petropavlovsk. Such feelings are further intensified by the context in which Russian speakers believe to be underprivileged on ethnic grounds and losing out to ethnic Kazakhs (Laruelle and Peyrouse Reference Laruelle and Peyrouse2007). Not feeling fully culturally represented in Petropavlovsk, could, however, weaken their meaningful relationship with that place. Thus, seeking to resist the changes perceived through the built environment, Russian speakers seem to hold on to and voice stronger cultural Russianness. The image of Petropavlovsk as a “Russian-speaking space” can be, in turn, understood as means to counter Kazakhness, projected upon them by the elites and neighboring Kazakhs.

Language and cultural norms, as this part demonstrates, certainly influence spatial perception, behavior, and use of space by the inhabitants. By narrating themselves as part of Russian-speaking Petropavlovsk, Russian speakers have strengthened their sense of belonging and understanding of this place. Yet to argue that Kazakhness remains at the margins of their lives, would be misleading at best.

Becoming Culturally Intimate with Kazakh

The term “cultural intimacy,” proposed by Michael Herzfeld in 1997, connotes “those aspects of cultural identity that are considered a source of external embarrassment but that nevertheless provide insiders with their assurance of common sociality” (Herzfeld 2005, 3). Cultural intimacy, which can be registered through numerous practices and aspects of everyday life, intensifies the connection to place and allows people to strengthen their sense of belonging not only to a locally rooted community but to the country in general. These practices and customs, however, due to their everyday familiarity and repetition often remain pre-reflective and beneath our conscious awareness. Borrowing the concept from Herzfeld, in this article cultural intimacy rather serves to emphasize those cultural traits and Kazakh traditions which Russian speakers often claim to be foreign in their conscious narration but those which are made permanent fixtures in their lives through regular performances and quotidian, unreflective everyday acts. This part, thus, focuses on the performativity aspect and examines how by performing certain rituals or by unconsciously acting, Russian speakers become culturally intimate with Kazakh. Performance here is a particularly useful term, as it signifies the notion of belonging as a dynamic process, as always being produced and re-produced.

When I arrived in Petropavlovsk, Pavel,Footnote 6 a supervisor in his mid-twenties working in a factory, agreed to accommodate me for the whole period of my stay. Pavel introduced me to his friends and family members, took me out to different parties and events in the city and was in general very kind to share his daily experiences and thoughts over dinner. Living in a flat with him and carrying out the daily routine together allowed me to have exceptionally deep insights into his life, his rituals, and interactions with the socio-political environment around him. Throughout the whole time, despite having German nationality indicated in his Kazakhstani passport,Footnote 7 Pavel claimed his Russianness on several occasions by emphasizing the richness of Russian history of which he is a part, by drawing boundaries between Russians and Kazakhs, and by often diminishing Kazakhs and calling them mambety (a derogatory term, meaning poor, uneducated and often predisposed to crime).Footnote 8 He furthermore emphasized his love for the Russian “kitchen.” Interestingly, according to Boym (Reference Boym1994, 147), during the Soviet times kitchens were actively used by people as sites of rituals of private conversation about the most important matters of public concern. While the tradition of long kitchen conversation seems to have its afterlife in the post-Soviet period, the meanings of it have shifted:

I mean the abstract understanding of it, where we have vodka, where the secrets are held, where the new thoughts are born. Particularly the “Russian kitchen,” and not the one where Beshparmak [Kazakh traditional dish] is being cooked, a kitchen that symbolizes Russian spirit and culture. (Pavel, 26, from a personal conversation in October 2016)

Disregarding the numerous moments when through active narration Pavel represented himself as a Russian,Footnote 9 he nevertheless unconsciously incorporated Kazakh rituals that with time and repetition, as I argue, became inscribed into his body. Perhaps the most exemplary would be the celebration of Kurban Bairam, a Muslim holiday, that took place in Kazakhstan between 10-12 September 2016. Already a week in advance Pavel announced that he would be making beshparmak for the weekend. On the actual day, he got up early and rushed to purchase horse meat (a key ingredient) at the market. After standing hours in a queue and spending even more hours in the kitchen, Pavel proudly called his guests to the table. This was the day when everyone in Petropavlovsk seemed to celebrate Kurban Bairam, both publicly while accompanied by the state-organized concerts and at home like us with beshparmak. I observed a very similar situation during Nauryz at the end of March 2017, while following the posts of my local friends online: people posted numerous photographs with Kazakh traditional food, sent regards to each other “Nauryz meiramy kutty bolsyn!” (congratulations on the holiday of Nauryz), and seemed in general very keen to follow the spirit of the public celebration communicated to them by the government.

Such conduct by Pavel and other collaborators could be described as an “incorporating practice,” by which groups or individuals transmit messages and reproduce socially habitual memory of past events through disciplined bodily performance (Connerton Reference Connerton1989, 72). According to Connerton (Reference Connerton1989, 13), in a ritual performance or everyday practices we tend to think and act following what is automatically incorporated into our bodies as a habit. Such practices and rituals are, thus, usually shaped by unreflective assumptions and dispositions. This becomes particularly visible through the discussion that took place between myself and Pavel on the messenger service WhatsApp, when I tried to understand briefly why we celebrated Kurban Bairam:

I: What was it again that we celebrated back then with Beshparmak?

P: Hi :) this was Kurban Bairam :) why? Do you want finally to try some horse meat? This is the main Muslim celebration.

I: I just remembered it, but couldn’t quite recall how it was called. Do you always celebrate it?

P: :) Of course not. In the end I am Russian.

I: Why did we celebrate it then?

P: I just wanted to eat Beshparmak that’s all

I: Why not on the other day then?

P: Horse meat is expensive, it is a “celebratory food” you know

I: And on that day they had a discount?

P: No… (Pavel, 26, from a WhatsApp conversation in December 2016)

The conversation demonstrates precisely the unreflective manner of the way certain performances are enacted. Being used to celebrating holidays alongside neighboring ethnic Kazakhs, the act gets so cemented in the habitual bodily enactments that it becomes practically an invisible part of the everyday life of Russian speakers. This argument contrasts with the accounts of Peyrouse (Reference Peyrouse2008b) and Laszczkowski (Reference Laszczkowski2016), who argue that Russian speakers often see themselves as losing out to ethnic Kazakhs in state national projects and are therefore reluctant to engage with Kazakh celebrations and traditions. While we might of course wonder whether Pavel was not simply playing “Kazakh,” play and real life should not be considered as distinctly separate realms. For example, Omasta and Chappel (Reference Omasta and Chappell2015) claim that play is a mimesis of a real life. In other words, through becoming the other in a timely limited act of play, the performer learns what it means to be the other and makes choices about one’s identity-in-role, and those choices become visible in the bodily actions and practices.

It is mostly through confrontation with different cultural codes in unfamiliar contexts that, according to Edensor (Reference Edensor2002, 89), such habitual performances, practical actions, sensations, and embodied habits become revealed to people. When Stepan, a beekeeper in his late thirties, found himself outside his everyday community by travelling to Russia, he sensed the longing for Kazakhstan and the Kazakhs:

I am so happy when I come back from Russia and see rodnikh [our dear] Kazakhs. I have two episodes. Once we went to the theater in Omsk and I started looking around – only Slavs, only pale Slavs. I was looking and looking. Then I found a Uyghur – a rodnoe [dear] face and clung to him the whole evening. Why did I do that? Rodnye [our dear] Kazakhs. Oh, and how much I love the dombra. I always put it to play at work or in the car. The second episode, I am on a metro in Ekaterinburg and again I look around – only Slavs, only Russians. I felt uncomfortable… (Stepan, 38, from a personal interview in August 2016)

Particularly interesting is the way Stepan employed the word “rodnoi” (our, dear, endemic), which in the Russian language stems from the root word “rod” (origin, species) and connotes familiarity, proximity and a sense of ownership. Sharing everyday lives with the Kazakh people became a habit for Stepan, a familiar milieu through which the affective and cognitive links with the Kazakh cultural community were strengthened. A similar situation was depicted by Iulia, who moved to Russia to acquire higher education:

Here, I miss the Kazakh mentality. I am so used to the ads in two languages, to tea with milk and beshparmak during every celebration. Petropavlovsk is a Russian-Kazakh city. Two cultures are entangled here. There is a lot of Russian habits in the lives of Kazakhs and in the lives of Russians– Kazakh. My mother drinks only Kazakh tea. She can even tell a Kazakh off for preparing it in a wrong way and teach him how to make the right one.Footnote 10 (Iulia, 21, from a personal interview in September 2016)

Such statements by my collaborators only strengthen the idea that Kazakhness is not only brought into the cityscape of Petropavlovsk and forcefully constructed top-down through the elite-level projects that seek to dilute the dominance of Russian culture, but is incorporated and re-enacted by people in their everyday lives and customs. While seemingly devaluating the cultural traditions of the dominant nation through the narratives of otherness, as demonstrated through the story with Pavel, they simultaneously become a source of unreflected pride to Russian speakers. Pride that differentiates them from other Russians in Russia and reinforces their sense of belonging to Petropavlovsk not as a “Russian-speaking space” but to Petropavlovsk as a multicultural Kazakhstani space, where Russian and Kazakh cultures are entangled.

Global Petropavlovsk

With recent migration trends, heightened interactivity between people and the reevaluation of the meanings of boundaries between nations and groups, there is a growing scholarly research agenda on the phenomenon of transnationalism and the aspects of “global” in people’s everyday lives. Indeed, according to Ulrich Beck (Reference Beck2002, 17), in the 21st century we can no longer understand the human condition nationally or locally, but only globally. Globalization as a dialectic process between the “global” and the “local” transforms and cosmopolitanizes nation-state societies from within by significantly changing everyday consciousness, experiences, life-worlds, and identities of people (Beck Reference Beck2002, 17–23). This part goes, therefore, beyond the simplistic binary representation of Petropavlovsk as a Russian or a Kazakh space. It adheres to the more recent trends in anthropology and examines how capitalist globalization and the changes in the technological and economic conditions, brought about by the latest phase of modernity, feed into the creation of new cultural forms and lifestyles of Russian speakers in this borderland city. In particular, it examines how forces from various metropolises are integrated locally and how such new urban conditions are experienced by people daily.

The “global” and the “local,” however, should not be perceived as cultural polarities. Rather these two concepts should be treated as dynamic processes, existing in an interactive relationship with each other (Appadurai Reference Appadurai1996; Hannerz Reference Hannerz.1996). Such entanglement is best observed in specific places: it can be cities, which according to Hannerz (Reference Hannerz.1996, 12) “have a major part in ordering transnational connections;” or it can be particular buildings, specific for the age of “globalization” (Laszczkowski Reference Laszczkowski2011, 86). While in this section I will briefly mention the overall attempts of the local authorities to modernize and to catch up with the pace-setting cities in Kazakhstan, Almaty and Astana, the major focus here is on specific places like cafes and bars, which through their form and content represent cosmopolitan transnational connections. By visiting such places, as I argue below, Russian speakers redefine Petropavlovsk as modern and themselves as subjects of urban geographies, as “cosmopolitan”Footnote 11 citizens.

Overall, there is a rather limited amount of studies that focus on, what Beck calls, “internalized globalization” in the cities of Kazakhstan. The latest research scrutinizes different ways how the ideas of modernity and progress are being used by the elites as a strategy to legitimate the regime (Koch Reference Koch2010) or as a frame of reference for national policy-making and planning (Bissenova Reference Bissenova2014). Laszczkowski (Reference Laszczkowski2016), furthermore, thoroughly examines how the meaning of urbanity is contested and negotiated by the individual actors who seek to establish themselves in the new emergent social configuration of Astana. The focus of such studies remains, however, on the major cities of Almaty and Astana. That being said, there is no single fixed standard of the “global.” While certain models and ideals travel across cities and countries, each site of urban transformation should be handled as “particular engagements with the world” (Ong Reference Ong2011, 2). Since the state modernization projects are unevenly distributed between cities, the idea of global and urban varies even within one country.Footnote 12

As Bissenova (Reference Bissenova2017, 4) notes, the continued urbanization of Astana and Almaty has been occurring at the “expense of de-urbanization and de-industrialization in many places” in Kazakhstan. Following post-Soviet restructuring policies and considerable depopulation due to outmigration, which continues today, cities like Petropavlovsk have been struggling to catch up with the pace of more progressive and successful urban centers. Yet it does not mean that the already mentioned “internal globalization” has bypassed Petropavlovsk. In fact, there are currently a variety of projects by the local authorities to improve the condition and standing of their own town vis-à-vis the others: ameliorating infrastructure, modernizing the central park by adding Japanese and English park-zones (the reconstruction works started in late summer 2017), renovating historical building complexes, and building malls and entertainment centers. As one of my respondents noted:

Our city improves yearly. You can see how they build roads, parks, they really build lanes, public squares. In the past year, they rolled (perekatali) almost half of the city. The situation here changes…Jokes that our city is grey, and the roads are bad no longer work. The city is being improved. It is good to live here, it is getting better locally and aesthetically. (Sergei, 25, from a personal interview in September 2016)

There are also numerous efforts by local businessmen to bring in a new urbanized lifestyle into Petropavlovsk, dictated, on the one hand, by the reach of the “global” forces of consumer capitalism, but also by the desire to create new places to go, on the other. In the past several years, the inhabitants of Petropavlovsk have witnessed the opening of several fitness studios that promote healthy lifestyles, cafes that disseminate the idea of coffee consumption as a style for a modern society, as well as restaurants and bars. Most of them are named in English or in other foreign languages (for example, Huston, Irish pub, Friends, Piccolino) and have an interior design which many readers would recognize as rather familiar. One of such places is a grill and bar “Marinad,” where some of my respondents took me while showing me around the city. “Marinad,” according to its website, seeks to break the stereotypes about the usual perception of a restaurant in Petropavlovsk, while its primary goal is to promote a new philosophy of eating – “sharing is caring” (the English phrase is used in the original Russian text). Following the words of my respondent Artem, this place is “branded (brendovoe), and corresponds to the very high standards due to its uncommon but tasteful interior and more expensive furnishing.” In “Marinad,” but also in other cafes and restaurants in Petropavlovsk, the idea of “worldliness”Footnote 13 finds precisely the expression in their references to and simulation of the diverse designer styles and architectural traditions stemming from foreign countries. The visitors come here for comfort, to eat steaks and pastas, to drink cocktails, to taste wine, and to socialize, while being served by very hip-looking waiters and waitresses. Although the prices are not the most democratic, especially for local inhabitants, the place is always filled with the guests.

According to Laszczkowski (Reference Laszczkowski2011, 98), as a part of a new urbanized lifestyle, places like malls, cafes, and restaurants become sites for negotiating identities, hierarchies of value as well as for expressing personal desires for affluence and advancement. Irina, a woman in her late thirties, who grew up in a nearby village and then moved to Petropavlovsk following her husband, talked to me about the importance of being financially stable and having the opportunity to go to places like “Marinad:”

I love earning money, and I am not ashamed of telling you this… For me to feel myself comfortable and calm at any place, I need money. Maybe I think this way, because for a very prolonged time I had serious financial problems. Maybe because of this… I need a sufficient sum, so that I could visit any places I like or buy any presents I want. (Irina, 38, from a personal interview in September 2016)

For Irina, Artem and my other respondents, cafes and bars often offer space to demonstrate their self-realization, as people who have made it in the global economy. Such socially situated practices of self-making come, of course, with the alignment with people, who share similar signifiers of a “cosmopolitan” lifestyle (such as clothes, consumables, music), against others, who represent a more traditional way of life. By coming together as people who can afford the new aspirational lifestyle, Russians and Kazakhs alike reevaluate the meaning of traditional boundaries between nations and cultures. However, while seemingly overcoming the old divisions between “Russianness” and “Kazakhness,” places like “Marinad” create new ones – between those who can afford such a lifestyle and those who are excluded from the joys of aspirational Petropavlovsk:

“Marinad” became too expensive and only more wealthy people go there now. They have wine tasting nights with a sommelier, can you imagine. We don’t go there anymore, it’s too expensive for us (Natasha, 19, from a WhatsApp conversation in October 2017).

Furthermore, similarly to what Bissenova (Reference Bissenova2017) and Laszczkowski (Reference Laszczkowski2016) note for Almaty and Astana, also in Petropavlovsk the ongoing outmigration of Russian-speaking urbanites to Russia and the arrival of Kazakhs from the southern countryside might in the future cause even more imbalances and divisions between the urban and rural population, between those regarded as modern and those regarded as backward elements of society. Such a situation might then lead to further contestation and renegotiation of the meaning of urbanity in Petropavlovsk.

Conclusion

By drawing upon mundane details of social interaction, habits, and routines in the daily lives of Russian speakers, this article provides some insights into the ways people differently construct the place they inhabit. The examples used here demonstrate how Russian speakers residing in the city of Petropavlovsk, close to the border with Russia, negotiate their complex individual position between various national, urban, and global cultural forms as well as their own understanding behind the meanings of Russianness and Kazakhness. The narratives from the interviews and close observations of symbolic practices show clearly that local, national, and global identities of Russian speakers are mutually entangled and are dynamically negotiated by individuals in place. While my respondents often framed the city as a “Russian-speaking space,” linked to the narratives of common Russian language, shared culture, and Russian mentality, I have demonstrated how local Russian speakers simultaneously adopt Kazakh cultural traditions in their mundane performances. Going beyond the simple dichotomy between Russian and Kazakh, this article has also depicted clearly how the everyday lives of Russian speakers are increasingly linked to the experiences of so-called “internalized globalization,” which arguably challenged the traditional national and cultural boundaries among my respondents. By frequenting cafes, bars, and restaurant, local Russian speakers not only sought to reinstate their self-realization and self-value as people who can keep up with the global economy, but in this process, they also aligned themselves with ethnic Kazakhs who shared with them similar signifiers of a modern lifestyle.

Overall, by conducting ethnographic research in Petropavlovsk, this study demonstrates how social processes within one country can differ, how meanings of Russianness and Kazakhness can change when travelling from one locality to another, from the capital to the periphery. Despite numerous antagonistic national projects by Kazakhstan, on the one hand, and by Russia, on the other, an overreaching sense of nationhood and national idea is highly contradictory when viewed from a particular locality. Instead, various mutually constitutive and at times contesting forms of urban, national, and global emerge through performances by people in place. This article, therefore, invites future research to consider these variances. Furthermore, rather than studying entanglements of the “global,” “national,” and “local” in the usual “global” capitals, to affirm the diversity in people’s experiences in place, more nuanced analysis should be conducted in the so-called “marginal” places and peripheries, which have so far received limited academic attention.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Bernardo Teles Fazendeiro and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on the drafts of this article.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the thematic DAAD-Netzwerk “Kulturelle Kontakt- und Konfliktzonen im östlichen Europa” at Justus Liebig University Giessen in cooperation with Herder Institut (Marburg).