Populism––A Threat to Democracy?

The global rise of populism has aroused concern about democracy’s survival, even in the United States (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Mounk Reference Mounk2018). After all, populist leaders, whether rightwing or leftwing, have shown clear authoritarian tendencies. Several populist chief executives, such as Alberto Fujimori in Peru, Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Viktor Orbán in Hungary, and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey, have in fact strangled democracy (Carrión Reference Carrión2006; De la Torre Reference De la Torre2013; Levitsky and Loxton Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013; Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018; Weyland Reference Weyland2013).

As the populist wave has engulfed advanced industrialized countries, such as Italy and in 2016 the United States, these fears have extended to longstanding liberal-pluralist regimes. Are these democracies truly immune, as political science automatically used to assume, or are they also vulnerable to gradual suffocation justified with strong popular mandates? Most contemporary populists do not destroy democracy through open power grabs, such as Fujimori’s self-coup of 1992. Instead, they leverage their institutional attributions as chief executives and the mass support certified by their initially democratic election to dismantle liberal pluralism gradually in formally legal or at least para-legal ways (Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018).

In principle, democracy in the advanced West could “die” (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018) by being coaxed down this slippery slope as well. Constitutions and laws always leave room for discretion, and limited violations may not draw effective sanctions. Indeed, during the interwar years, elected leaders dismantled some European democracies from the inside; even fascist Hitler had considerable formal-legal cover for his resolute push toward mass-acclaimed dictatorship.

Because populist politicians can misuse democracy to abolish democracy, democratic institutions look vulnerable. As both presidential systems (in Peru and Venezuela) and parliamentary systems (in Hungary and Turkey) have fallen, and as chief executives with weak formal attributions have managed to move toward authoritarianism,Footnote 1 the framework of official rules and procedures may be rather defenseless. Perhaps savvy agency can escape from and overcome virtually any kind of institutional constraints?

As I argue, however, the concerns that even advanced democracies are vulnerable to populist leaders’ corrosive tactics seem exaggerated. Shocked by fascism’s rise during the interwar years and by prominent recent cases of populist moves toward authoritarianism, the burgeoning literature about threats to U.S. democracy overestimates the openness of institutions to legal transformations or forceful para-legal change (see especially Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018). Yet these tragedies affected only new, precarious democracies during the 1920s and 1930s in Europe and institutionally weaker polities in Latin America and Eastern Europe during recent decades. In the interwar era, the longstanding democracies of Northwestern Europe proved immune to fascism (Cornell, Møller, and Skaaning Reference Cornell, Møller and Skaaning2017) which bodes well for the longstanding democracies of the advanced industrialized world during the recent upsurge of populism.

In fact, even in the weaker institutional settings of contemporary Latin America and Eastern Europe, many populist leaders have failed with their authoritarian machinations. Observers are overly impressed and scared by the relatively few cases of undemocratic involution. They pay insufficient attention to the many more instances when populist efforts to undermine democracy were blocked; after all, non-cases are by nature less prominent. Yet while studies that examine only the outstanding cases of authoritarian regression can demonstrate “how democracies die” (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; similarly Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2019; Reference PrzeworskiPrzeworski forthcoming, 103-5), they cannot assess the actual likelihood of this tragic outcome and identify the conditions under which it occurs and when not. To overcome this skewed focus and offer a balanced, systematic assessment of the real danger facing liberal democracy, my analysis examines the regime impact of populist chief executives in a comprehensive set of cases from Europe and Latin America (for a somewhat similar effort, see recently Pappas Reference Pappas2019, chap. 4, 7).

This wide-ranging investigation shows that populist efforts to dismantle democratic institutions and promote authoritarianism succeed only under special conditions. Two sets of factors need to coincide. First, institutional weakness provides an opening for the populist suffocation of democracy. Second, a huge resource windfall or clear success in overcoming acute, severe crises gives populist leaders massive support and allows them to remove the remaining obstacles to authoritarian power concentration. When either one of these conditions is absent, populist machinations fail and democracy survives.

One crucial precondition for the populist strangulation of democracy is a weak institutional framework. Some types of institutions are, by configurational design, fairly open to change and thus enable pushy leaders to dismantle democracy in formally legal ways. Other frameworks lack firmness and resilience so that powerful chief executives can bend or break formal rules, override official institutional constraints, and destroy democracy para-legally (Levitsky and Murillo Reference Levitsky and Murillo2009; Brinks, Levitsky, and Murillo Reference Brinks, Levitsky and Murillo2018). My analysis shows that some kind of institutional weakness, as classified later, is a necessary condition for populists to smother democracy.

Yet even weak institutions hinder populists’ authoritarian machinations. Consequently, democracy succumbed only under a second precondition: when populist politicians won office in countries plagued by acute yet resolvable crises or blessed by huge hydrocarbon windfalls. The enormous benefits that populist leaders can provide as providential saviors from a looming catastrophe or as distributors of extraordinary wealth gave them huge mass support, which allowed them to override political opposition and push through institutional transformations to concentrate power and disable checks and balances. By contrast, populist executives who lacked such largely exogenous opportunities rarely obtained overwhelming backing; therefore, their authoritarian projects ran aground various obstacles, and democracy persisted. Thus, even in weaker institutional settings, democracy’s destruction is difficult and often fails. Populism’s regime impact is much more mixed than recent warnings suggest.

In sum, only a pernicious combination of institutional weakness, which makes democracy vulnerable to populist assaults, and conjunctural opportunities that give populist leaders overwhelming support for authoritarian projects, proves fatal for democracy. Where these conditions do not coincide, populist chief executives have not managed to strangle democracy. The frequency of blocked or failed efforts suggests that populism’s recent upsurge does not pose the grave risks that many observers dread.

In particular, the longstanding democracies of advanced industrialized countries like the United States seem rather safe. First, these nations boast considerable institutional strength, which fosters immunity to populist assaults. Indeed, with the passage of time, democracies achieve a substantial boost in immunity not only against coups, but also against “incumbent takeovers,” which includes suffocation by democratically elected populists (Svolik Reference Svolik2015, 730-34). Due to this significant leap in institutional solidity, liberal regimes that have lasted for about sixty years face only an infinitesimal risk of falling to any authoritarian tricks by elected chief executives. This resilience protects democracies in the West, including the United States. Second, advanced industrialized countries rarely suffer devastating crises (Wibbels Reference Wibbels2006), nor are their diversified economies flooded by huge resource windfalls. Therefore, populist leaders cannot garner overwhelming mass support and remove the institutional constraints protecting democracy.

To substantiate these arguments and derive inferences about the risks posed by President Trump, my comparative investigation of the conditions for populists’ asphyxiation of democracy focuses on Europe and Latin America. Among world regions, these areas are most similar to the United States, which facilitates lesson drawing (cf. Weyland and Madrid Reference Weyland and Madrid2019). Moreover, Europe and Latin America feature the most cases of populist chief executives. By the logic of “most similar systems” designs, these regions therefore allow for systematically assessing populism’s regime impact, which is harder to infer from the sporadic instances of populism in a heterogeneous continent like Asia.

To anchor the analysis, section two explains populism’s inherent threats to democracy. Then sections three to five discuss different types of institutional weakness, which are necessary conditions for populist leaders to overcome the constraints embodied in democratic institutions. Yet as section six highlights, populist chief executives can only move to authoritarianism if they also face exogenous opportunities arising from acute crises or huge windfalls that provide them with massive support. By scoring a wide range of populist experiences, section seven shows that only the combination of institutional debility and conjunctural opportunities proves fatal for democracy. Drawing inferences from this comparative investigation, sections eight and nine highlight the low likelihood that populism will bring an undemocratic involution in the United States. Instead, as section ten argues, President Trump’s populism may inadvertently spark a revitalization of U.S. democracy.

Populism: Inherent Tendencies toward Authoritarianism

Theoretically, there are good reasons for concern about populism’s threat to democracy, conceived here in standard “Dahlian” terms and therefore used interchangeably with “liberal pluralism.” This authoritarian danger is rooted in the very nature of populism. My analysis of the regime impact of populist leadersFootnote 2 defines populism “as a political strategy through which a personalistic leader seeks or exercises government power based on direct, unmediated, uninstitutionalized support from large numbers of heterogeneous followers” (Weyland Reference Weyland, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017, 59). Centered on the person of the leader and sustained by quasi-personal connections to masses of people, populism revolves around personalistic plebiscitarian leadership, rests on unbounded agency, and resists institutionalization. Because institutions would constrain the leader’s latitude and impede their quest for unchallenged predominance, populism stands in unavoidable tension with institutionalization as such.

By contrast, liberal democracy relies on strong, firm institutions to prevent the abuse of power and protect individual liberty. This institutional framework is enshrined in law and therefore impersonal. The crucial foundation is a hard-to-change constitution that guarantees ample individual freedoms and political rights, keeps state coercion to the necessary minimum, and restricts the majority’s capacity to rule.

No wonder that populist leaders see liberal democracy as an enormous obstacle to their personalistic plebiscitarian strategy! To maintain and boost their leadership, they constantly need to prove and enhance their own preeminence. Because institutions hem in their willfulness, they disrespect or try to dismantle checks and balances. To achieve the extraordinary, “supernatural” feats that certify their outstanding position (Weber Reference Weber1976, 140), these often-charismatic politicians seek to augment their power as chief executives and attack or take over the other branches of government. Resting on mass admiration for its bold activism and lacking the organizational discipline that could guarantee reliable support, populist leadership can never stand still but feels compelled constantly to expand its latitude and clout. This innate dynamism systematically tries to corrode the institutional constraints essential for democracy, opportunistically taking advantage of any chance that arises.

For these reasons, populism poses serious threats to democracy. Personalistic plebiscitarian leadership is by nature antagonistic to liberal checks and balances and jeopardizes fair competitiveness, democracy’s core (Schmitter Reference Schmitter1983, 889-91). In recent decades, several populist leaders have indeed destroyed democracy. Fujimori, Chávez, Orbán, and Erdoğan, as well as Ecuador’s Rafael Correa and Bolivia’s Evo Morales (Levitsky and Loxton Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013; Weyland Reference Weyland2013),Footnote 3 stand out: They all obstructed effective opposition, squeezed civil society, controlled the media, abused government resources and power, and seriously skewed competition, practically guaranteeing their own hegemony. In these ways (cf. Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010, 5-13), they installed “competitive authoritarianism.”

Populist Agency versus Institutional Constraints

Because populism’s personalistic plebiscitarian leadership stands in inherent tension with the strength of the existing institutional constraints, populist chief executives are hobbled and cannot do lasting damage to democracy where checks and balances are tight and firm. Yet where institutions leave room for discretion; where they are easy to disrespect with impunity; or where they can be dismantled or transformed at will, there is a real risk of democratic involution. Thus, institutional weakness is a crucial permissive cause for authoritarian backsliding promoted by populist politicians; conversely, institutional strength and stickiness protect liberal pluralism. Of course, institutions are not fixed, and populist leaders ceaselessly work to loosen institutional constraints. But the very success of these illiberal efforts depends on the firmness of the pre-existing institutional framework. In the interconnected world of politics, where few causes are truly in-dependent variables, the institutional setup that populist leaders encounter upon taking office seriously conditions their power-concentrating and undemocratic machinations.

The openings that institutional structures leave for sneaky populists depend not only on institutional design and configuration (e.g., parliamentarism versus presidentialism), but also on the underlying strength of the institutional framework as such. As institutionalists have long emphasized (Huntington Reference Huntington1968; Mainwaring and Scully Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995; Elkins, Ginsburg, and Melton Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2009; Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring2018; Brinks, Levitsky, and Murillo Reference Brinks, Levitsky and Murillo2018), political systems vary greatly on this fundamental factor. Two dimensions of institutionalization seem particularly important: the degree of compliance that institutions can command, and their stickiness and endurance (Levitsky and Murillo Reference Levitsky and Murillo2009).

Accordingly, institutions are weak, first, where they cannot effectively shape behavior, but are commonly disrespected with impunity; if enforcement is lax and actors simply fail to follow the official rules, formal institutions lack relevance. Second, institutional weakness also prevails where institutions can be changed at will. Malleable institutions do not constrain current power holders; instead, they turn into instruments that incumbents can use to pursue their goals, including the concentration of power and curtailment of the opposition. The law then serves not as essential scaffolding of democracy, but as a building block for authoritarianism (Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018).

These two dimensions suggest a simple typology with three forms of institutional weakness, resulting from the possible combinations of easy changeability and weak compliance. Consequently, political regimes suffer from institutional weakness if they are highly susceptible to legal changes of formal rules; if there is widespread, unsanctioned disrespect of formal rules; or—in combination—if powerful actors can employ para-legal or illegal means and simply impose transformations of formal rules.

First, some institutional frameworks facilitate their own fully legal transformation through electoral rules that produce disproportionate majorities, and through regime institutions that create weak checks and balances and set low thresholds for revamping the constitution. Such weakness via easy changeability creates the biggest risk for democracy in advanced countries because it allows populist leaders gradually to dismantle and suffocate liberal pluralism through a sequence of perfectly legal measures, which are more difficult to oppose than open violations and forceful impositions.

A second type of institutional weakness prevails where violations of formal rules are common and do not draw effective sanctions. If rules lack bite and political actors get away with arbitrary measures, they can move toward authoritarianism while leaving a pristine set of democratic rules on the books. But such an open gulf between the legal framework and actual political practice is problematic by offering a wedge for domestic opposition and by provoking international criticism.Footnote 4

What is therefore much more common, for purposes of domestic and international legitimation, is the third, combined pattern, especially in sequence: Para-legal or illegal measures remove institutional obstacles to the transformation of the constitutional framework. Often, the initial breach entails the imperious convocation of a constituent assembly, which redesigns major regime institutions by augmenting the attributions of the chief executive, weakening mechanisms of horizontal accountability, and introducing direct-democratic procedures designed to engineer plebiscitarian acclamation. Thus, where powerful actors can disregard existing rules with impunity, they often—in a seemingly paradoxical but entirely logical fashion—use violations to impose a new institutional framework that fortifies their own position; then they enforce the new rules against the opposition.

What threats to democracy arise from these types of institutional weakness? The next two sections examine experiences in which populist leaders tried to pursue their authoritarian goals by taking advantage of the two most feasible avenues, namely easy legal changeability or the para-legal imposition of new institutions. With what likelihood and under what conditions did they succeed with their nefarious plans?

Openness to Institutional Change: How Much Risk for Democracy?

In their formal design, some institutional frameworks—especially Lijphart’s (1999, chap. 2) majoritarian “Westminster model”—are open to legal transformation because they facilitate the formation of lopsided majorities and stipulate low requirements for constitutional amendments. Other regimes, by contrast, make such alterations very difficult or proclaim basic principles as unalterable. The U.S. Constitution, for instance, is hard to reform because in addition to supermajorities in both houses of Congress, three-quarters of the states have to approve any change.

Due to comparatively weak checks and balances in its formal-institutional configuration and its low number of “institutional veto players” (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1995), parliamentarism is, as an institutional framework, more susceptible to legal rule changes than presidentialism.Footnote 5 If prime ministers can count on firm majority support in the legislature (see section six on the crucial role of economic crises), they can with relative ease overhaul infra-constitutional rules, including electoral laws. By exacerbating disproportionality, these changes in turn help engineer an overwhelming parliamentary majority, which can then allow for “taking over” the courts, approving constitutional amendments, or summoning a constituent assembly.Footnote 6

Parliamentarism’s greater openness to change enabled Viktor Orbán to effect a quick institutional transformation that pushed Hungary away from liberal democracy. In 2010, electoral rules that guaranteed the winner disproportionate seat shares gave his party Fidesz a 68% majority in the unicameral parliament. The populist leader used this predominance to take advantage of Hungary’s constitutional flexibility (Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018, 549-50). In 2011, he had parliament approve a new charter that increased prime-ministerial powers and weakened liberal safeguards (Körösényi and Patkós Reference Körösényi and Patkós2017, 324-25). Moreover, Fidesz eroded judicial independence and further skewed the electoral system, which then gifted the dominant party with lopsided majorities in 2014 and 2018 (Bozóki Reference Bozóki, Krasztev and Van Til2015, 16-21). Facing relatively weak checks and balances in Eastern Europe’s “most majoritarian” democracy (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2018, 1490), the Magyar populist thus advanced toward authoritarianism with ease. Given the perfect legality of his machinations, the European Union proved unable to stop this suffocation of democracy.

After his electoral victory in 2002, Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan similarly took advantage of the openings provided by parliamentarism and a fairly flexible constitution (Yegen Reference Yegen2017). Interestingly, the Turkish populist first established the domestic and international legitimacy of his moderately Islamist government by initially promoting liberal pluralism. In this way, he sought to push back an overbearing military that had since Atatürk’s times exercised veto power over civilian governments to enforce secularism. Only after Erdoğan had broken the military’s stranglehold and consolidated his grip over Turkish politics did he resolutely spearhead an illiberal turnaround (Dinçşahin Reference Dinçşahin2012). He cemented his political hegemony and command over the state, coopted, divided, and combated the opposition, and put increasing pressure on the press and civil society. After a failed coup attempt in 2016, he further intensified his attack on liberal pluralism with large-scale purges and mass arrests. To seal his political predominance and bury democracy, he engineered a constitutional change, especially a switch from parliamentarism to presidentialism with himself as the all-powerful president (Aytaç and Elçi Reference Aytaç, Elçi and Stockemer2019, 93-101).

As these two experiences of democracy’s self-destruction show, parliamentarism with its attenuated separation of powers, especially when combined with unicameralism and constitutional flexibility, can in principle allow for perfectly legal institutional transformations that gradually establish authoritarianism (Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018).

This risk depends, however, on additional conditions that are not often fulfilled. After all, most parliamentary systems use proportional representation for elections, which fosters multi-party systems and creates several “partisan veto players” (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1995). Indeed, in Europe’s ever more complex and heterogeneous societies, parties have proliferated as the old catch-all parties have lost support to new contenders; yet those formerly predominant parties have not collapsed and continue to limit the space for newcomers, including populists. Therefore, one party, including a populist movement, can rarely win a clear majority, not to speak of a supermajority that permits the easy approval of constitutional amendments. The special conditions that allowed Orbán and Erdoğan to achieve this feat—namely, economic crises—are discussed in section six on the crucial role of exogenous opportunities.

The political obstacles arising from party fragmentation have hobbled populist leaders in several of Europe’s parliamentary systems. Vladimír Mečiar in Slovakia, for instance, pursued similar illiberal goals as Hungary’s Orbán, in a polity that allowed for easy constitutional change (Fish Reference Fish1999, 53-54). But because Mečiar’s party lacked a parliamentary majority, his efforts to establish political hegemony were weakened by his unreliable coalition partners. Trying to overcome these limitations through blatant power grabs, the Slovak populist provoked such revulsion in civil society that the opposition defeated him in the 1998 elections (Deegan-Krause Reference Deegan-Krause, Weyland and Madrid2019). Similarly, when the multi-party coalition government of Robert Fico in Slovakia trampled on liberal rights, this populist leader was unseated through opposition-led mass protests in 2018. Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš has also been hindered in his anti-pluralist machinations by the lack of a parliamentary majority (Hanley and Vachudova Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018, 277, 283, 289).

For similar reasons, liberal democracy survived Silvio Berlusconi’s populism in Italy (Taggart and Rovira Reference Taggart and Rovira2016, 351-52). As his Forza Italia never won a majority, he had to ally with obstreperous rightwing parties. Therefore, the condottiere’s governments were always precarious and lacked the clout to transform the institutional order (Körösényi and Patkós Reference Körösényi and Patkós2017, 319).Footnote 7 Intra-coalitional disagreements marred a major effort at constitutional reform, which sought to strengthen prime-ministerial power – a crucial step toward illiberalism. But because Berlusconi’s divergent partners insisted on various other amendments, the overall reform package was an incoherent, unwieldy Frankenstein. Differences among the allied parties also weakened their campaign for the constitutional referendum, which ended in defeat (Bull Reference Bull2007, 100-4, 107-9).

Moreover, Berlusconi’s autocratic tendencies were held in check by a judiciary that had emerged strengthened from the prosecution of massive corruption under preceding governments (Dallara Reference Dallara2015). Last but not least, the independent media and civil society eagerly exposed the prime minister’s personal and political scandals, which contributed to electoral losses and the defection of partisan allies, and finally forced Berlusconi’s resignation in 2011 (Fella and Ruzza Reference Fella and Ruzza2013, 39-42, 45, 48; Verbeek and Zaslove Reference Verbeek and Zaslove2016, 311-18).

Thus, even where populist leaders win power in parliamentary systems, they often face various obstacles that protect democracy. These difficulties are even more pronounced, and the political damage minimized, where populist politicians are junior partners in governing coalitions. Under these circumstances, the charismatic leader may not find room inside the cabinet, as happened to Austria’s Jörg Haider in 1999. From this awkward position, a populist movement cannot threaten liberal democracy; instead, it risks serious setbacks, which Haider’s party indeed suffered.

In conclusion, parliamentary systems are lacking in institutional veto players, but often compensate for this vulnerability with multiple partisan veto players (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1995). The resulting political friction creates obstacles for populist leaders, who cannot take advantage of parliamentarism’s institutional openness. Due to the broader institutional and political setting, parliamentarism’s easy susceptibility to rule changes often does not create the big risks to democracy that the formal-institutional design would suggest.

The Para-Legal Imposition of Change: How Grave a Danger?

In presidential systems, by contrast, some populist leaders have strangled democracy by simply imposing institutional transformations in para-legal or illegal ways. Overbearing chief executives claimed powers that they officially did not possess, such as the right to convoke a constituent assembly. Then they deterred other branches of government from challenging these arrogations or blithely disrespected desist orders, invoking the popular legitimacy arising from clear electoral victories and overwhelming mass support (cf. Linz Reference Linz1990, 53-54, 64-65). Predictably, the constitutional conventions summoned with these strong-arm tactics did the populists’ bidding: they boosted presidential powers, allowed for reelection, and undermined checks and balances, for instance by abolishing the upper chamber of Congress.Footnote 8 Thus, the initial breach of rules enabled the imposition of a new institutional framework with weak safeguards and strong majoritarianism, tailor-made for populist authoritarianism (Levitsky and Loxton Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013; Weyland Reference Weyland2013).

These efforts to force through institutional transformations are particularly common in Latin America, where institutionalization often reaches only middling levels (Levitsky and Murillo Reference Levitsky and Murillo2009; Brinks, Levitsky, and Murillo Reference Brinks, Levitsky and Murillo2018), yet where presidential systems with their officially strict checks and balances impede the fully legal transformation of the constitutional order that European parliamentarism permits. Populist leaders in particular, who rise through confrontation and polarization, cannot muster the voluntary consent of other branches of government that would be required for the formal approval of constitutional amendments, not to speak of a new charter. Instead, new populist presidents normally face strong, often majoritarian opposition in Congress and encounter courts full of judges appointed by the old “political class.” Their efforts at constitutional transformation are therefore bound to meet resistance from these veto players.

Undeterred by formalities, which they decry as illegitimate obstacles to realizing “the will of the people,” populist leaders simply try to impose their will by exploiting the lack of institutional strength. Chávez overrode legal prohibitions and convoked a constituent assembly by decree (Brewer-Carías Reference Brewer-Carías2010, 48-55). Ecuador’s Rafael Correa had the electoral authorities sack the majority of opposition deputies in Congress (De la Torre Reference De la Torre2013). Bolivia’s Evo Morales disregarded the qualified-majority rule for approving new constitutional provisions (Lehoucq Reference Lehoucq2008, 118-20). Most blatantly, Fujimori closed congress and the courts with a self-coup and then engineered a new charter (Carrión Reference Carrión2006).

Where these impositions went forward, the populist redesign of the constitution often turned into a continuous process as power-hungry leaders constantly sought to fortify and extend their hegemony further. For instance, the charters redesigned by Fujimori, Chávez, and Morales allowed for one consecutive reelection. But during their second terms, all these presidents pushed for prolonging their tenure through various tricks. Peru’s Congress approved an Orwellian “law of authentic interpretation of the constitution” that permitted Fujimori to run again. Chávez called a plebiscite to lift presidential term limits in 2007; after he lost, he simply organized another referendum in 2009 and finally won. Morales reneged on a compromise with the opposition, refused to count his first term, and ran for a second reelection. Then, to bid for yet another term, he held a referendum to allow for unlimited reelections. After he lost in 2016, he pushed the government-controlled courts to permit his renewed candidacy. Step by step, these populists thus trampled democracy to death.

Populist presidents’ breach of formal rules carried political costs and serious risks, however. Even in relatively weak institutional settings, disrespect for existing laws and the illegal imposition of change face resistance, which has in recent decades increased with domestic modernization and the global diffusion of liberal principles and democratic norms. This legalization of politics has made forceful impositions, which used to be common in Latin America, more difficult.

Therefore, a number of Latin American populists did not succeed with para-legal machinations or open infringements of the institutional framework; others ceded to opposition and reluctantly abandoned such efforts. For instance, Guatemala’s Jorge Serrano, an outsider politician with populist features, saw his effort fail to follow Fujimori’s example by spearheading a self-coup in 1993 (Cameron Reference Cameron1998). Honduran conservative turned populist Manuel Zelaya, who like Chávez pushed in para-legal ways for a constituent assembly, fell in 2009 to a military intervention ordered by the Supreme Court and endorsed by the democratically elected Congress (Ruhl Reference Ruhl2010); soon thereafter, the country held new presidential elections and emerged from this irregular situation.

Moreover, Argentina’s neoliberal populist, Carlos Menem, had his crass overuse of decree powers reined in through constitutional reform in 1994, and his effort to run for another reelection was foiled by internal opposition in 1998–1999. Brazil’s Fernando Collor de Mello, unable to extinguish inflation, did not push through a constituent assembly, as his economically successful counterparts Fujimori and Menem did. Álvaro Uribe in Colombia respected a plebiscite defeat in 2003 and complied with a Constitutional Court ruling in 2010 that barred his plan of another reelection (Weyland Reference Weyland2013, 26). And when the entourage of Argentina’s Cristina Fernández de Kirchner floated the idea of lifting term limits in 2012, massive opposition protests and low popularity ratings blocked this move. Thus, numerous populist presidents in Latin America have not managed to force through power-concentrating institutional reforms that could have paved the way toward authoritarianism.

Populists’ frequent failure to concentrate power and destroy democracy is remarkable because many Latin American countries where personalistic plebiscitarian politicians won the presidency suffer from deficient institutionalization. While political science lacks a general measure of this important causal factor (Brinks, Levitsky, and Murillo Reference Brinks, Levitsky and Murillo2018, 51-64), certain indicators are instructive. For instance, do presidents manage to serve out their regular terms or are there extra-procedural evictions? Also, how durable have constitutions been (cf. Lutz Reference Lutz1994; Lorenz Reference Lorenz2005)? By these criteria, Latin American countries with populist presidents have not boasted great institutional strength; in fact, several cases where serious democratic backsliding occurred suffered from particular institutional weakness.

Indeed, Latin America’s recent wave of leftwing, “Bolivarian” populists who gradually suffocated democracy (Levitsky and Loxton Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013; Weyland Reference Weyland2013) emerged in countries of especially high instability. During the decade before the election of Morales and Correa, mass protests had driven two presidents from power in Bolivia, and three in Ecuador. Moreover, Ecuador had adopted a new constitution in 1998, a mere decade before Correa pushed through another charter; and Bolivia had enacted a major constitutional reform in 1994, twelve years before Morales initiated his own overhaul (cf. Brinks, Levitsky, and Murillo Reference Brinks, Levitsky and Murillo2018, 50, 62). Venezuela, in turn, had since national independence gone through twenty-six constitutions, the third-highest number in the world (Elkins, Ginsburg, and Melton Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2009, 23, 26). The decade before Chávez’s election had been rocked by two dangerous coup attempts in 1992, which triggered a politicized presidential impeachment in 1993. Such battered, fragile democracies were especially vulnerable to the para-legal imposition of change and offered little resistance to populist power grabs.

Other Latin American countries, by contrast, scored higher on those two indicators of institutional strength. Argentina, for instance, revived its 1853 constitution upon re-democratization in 1983. After Menem’s election, his predecessor stepped down a few months early, but in voluntary resignation. When Brazil emerged from military rule, the country adopted a new charter in 1988, but during the two decades preceding Collor’s election in 1989, every one of his predecessors—even the generals in power until 1985—had served out their full official terms. And in Colombia, which replaced its 1886 constitution in very participatory and consensual ways in 1991, no chief executive since re-democratization in 1958 had suffered a premature eviction, despite a worsening drug war and persistent guerrilla challenges.

This greater institutional strength helps explain why democracy survived the undemocratic machinations of populist leaders. At the middling levels of institutionalization prevailing in much of Latin America, however, this relative advantage is not alone decisive. Before Fujimori’s takeover, Peru showed surprising institutional resilience as the three presidents governing from 1975 to 1990 served out their full terms, despite drastically worsening economic and security problems, especially under Alan García (1985–1990); but even that inept president avoided a premature ouster. The next section highlights the crucial conjunctural opportunities that enabled some populist chief executives to override existing institutional constraints and strangle democracy––something other personalistic plebiscitarian leaders could not do.

Before examining the impact of these conjunctural opportunities, however, it bears summarizing the main points of the analysis so far, which have distinguished three types of institutional debility. First, the preceding section discussed the comparatively easy changeability of European parliamentary systems. The present section then examined two levels of institutional weakness in Latin America, namely the vulnerability of many presidential systems to para-legal change; and, more dangerous than this middling level of institutionalization, the high instability afflicting some polities, as indicated by irregular evictions of presidents.

The Crucial Role of Exogenous Opportunities: Acute Crises or Huge Windfalls

While the three types of institutional weakness create vulnerabilities, these debilities alone do not condemn democracy to death, as the very mixed success of populist power grabs shows. Even institutions of limited resilience hinder the dismantling of checks and balances and the imposition of undemocratic hegemony. Populist chief executives managed to overcome these institutional constraints and move toward authoritarianism only if they benefited from exogenous opportunities that greatly boosted their mass support and allowed them to legally disassemble or para-legally override and deform the established liberal-pluralist framework.

My inductive research suggests that the three types of institutional weakness were vulnerable to populist assaults boosted by different kinds of conjunctural opportunities. While in their quest for power concentration, populist leaders took advantage of any opportunity they encountered, there was an interesting pattern: The greater the institutional debility, the lower the exogenous impetus that populist chief executives needed for destroying democracy. Accordingly, in polities of particular institutional weakness, namely in parliamentary systems or cases of high instability, a single shock––though of two different kinds––allowed populist leaders to move toward authoritarianism. By contrast, in polities of intermediate resilience, namely presidential systems susceptible to para-legal change, only the unusual coincidence of two grave challenges permitted the suffocation of democracy.

In Latin America’s presidential systems of middling institutional strength, liberal pluralism fell to populist power grabs only under exceptional circumstances, in the single case of Peru. Upon taking office, Fujimori faced both disastrous hyperinflation (3,400% in 1989) and a dangerous guerrilla war: The brutal Shining Path inflicted mass terror while police and military responded with equal cruelty, causing a combined death toll of 69,000 citizens. No wonder that this populist leader won 80–85% approval when closing Congress and the courts with the claim that only unrestricted presidential predominance could effectively combat those two grave challenges (Carrión Reference Carrión2006). Thus, a severe double crisis allowed Fujimori to prove his bold agency, bring drastic relief, and garner the overwhelming popularity required for imposing constitutional change.

Among polities of intermediate institutional strength, Peru’s descent into populist authoritarianism was unique. Like Fujimori, Brazil’s Collor won the presidency during a hyperinflationary surge, but contrary to his Peruvian counterpart, he did not manage to resolve this economic crisis. Therefore, the Brazilian populist suffered striking political failure, culminating in ignominious impeachment (Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Rovira Kaltwasser, Weyland and Madrid2019, 43-45).

Remarkably, even presidents who managed to resolve one grave challenge did not win the massive clout required for strangling democracy. Like Fujimori—and different from Collor—Argentina’s Menem defeated hyperinflation, but did not manage to perpetuate himself in power and asphyxiate democracy; and like Fujimori, Colombia’s Uribe successfully fought large-scale guerrilla insurgencies, but saw his bid for further reelection blocked like Menem. Consequently, success in overcoming one grave crisis does not seem sufficient for producing the steamroller of support that enables a populist leader to push aside medium-strong institutional constraints. Fujimori only gained this blank check by successfully combating two severe crises, an economic crisis (operationalized as inflation above 50% per month or GDP drop worse than –5% per year) and a security crisis (armed challenge by more than 5,000 insurgents). Only an unusual cumulation of acute, grave, yet resolvable problems enabled populists to destroy democracy in Latin America’s presidential systems of intermediate institutional strength.

While populist leaders deliberately highlight and even exaggerate crises, the problems plaguing Peru had clear objective urgency and inflicted concrete, painful losses on broad population sectors. Thus, populists may “perform” crises (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016, chap. 7), but they cannot invent them; and to avoid blame, they cannot engineer crises either. Instead, crisis is mostly an exogenous factor. Acute, severe problems are largely “given” conditions that allow some personalistic plebiscitarian leaders to win massive backing; the absence of such challenges precludes this chance for others.

By contrast to presidential systems of middling institutional strength, it did not take a Peruvian-style double shock for democracy to succumb to populist machinations under conditions of great institutional debility and high instability. In Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, a largely exogenous windfall of benefits allowed personalistic plebiscitarian leaders to dismantle liberal pluralism. In line with the ample literature on the resource curse (Ross Reference Ross2015, 243-48), the oil and gas price boom of the 2000s gifted Chávez, Morales, and Correa enormous extra revenues.Footnote 9 These populist presidents could practically “buy” support with generous social programs for the broader population, juicy contracts for businesspeople, and the general bonanza created by the hydrocarbon windfall. Majoritarian backing allowed these “Bolivarian” leaders to override institutional constraints, establish unchallengeable hegemony, and suffocate liberal democracy.Footnote 10

The manna from heaven was especially crucial for the political survival of Chávez, who was projected to lose an opposition-demanded recall referendum in 2003. But by stalling for months, Venezuela’s savvy populist managed to take advantage of drastic oil price rises: He rapidly rolled out major social benefit schemes and thus engineered a victory when the vote was finally held in 2004. By contrast, Lucio Gutiérrez, who followed Chávez’s “Bolivarian” populism to win Ecuador’s presidency in 2002, but governed right before the huge hydrocarbon windfall, ruined his political chances by imposing economic adjustment. Deprived of support, he was driven from office in 2005, and democracy survived.

Recent developments in Ecuador confirm the exogenous roots of this resource curse, “in reverse.” The oil price collapse of 2014 quickly caused serious economic problems and triggered mass protests, which induced autocratic incumbent Correa to forego another reelection in 2017. Interestingly, his handpicked successor Lenín Moreno, tasked with cleaning up the mess and then allowing for the undemocratic populist’s return in 2021, broke with Correa and blocked his future reelection. To sustain this dramatic rupture, Moreno reached out to the partisan opposition and civil society, initiating a determined re-democratization (De la Torre Reference De la Torre2018; Pappas Reference Pappas2019, 257). This salutary outcome corroborates the impact of hydrocarbon booms and busts on the political fate of populist leaders and on the fate of liberal pluralism under conditions of particular institutional debility and high instability.

Turning to the third type of institutional weakness (discussed first in section four on openness to institutional change), the comparatively easy changeability of European parliamentarism allowed populist leaders to dismantle democracy if they received a popularity boost from antecedent economic crises. Interestingly, in these polities, which are fairly open to legal transformations, an economic crisis was sufficient, rather than the double-catastrophe that empowered Fujimori to impose authoritarian change in Peru’s medium-strong presidential system. Specifically, these economic crises enabled European populists to win parliamentary majorities. This unusual electoral success eliminated partisan veto players (cf. Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1995), which often obstruct nondemocratic transformations under parliamentarism.

Accordingly, Hungary’s Orbán benefited politically from the global collapse of 2008. The GDP drop of -6.6% in 2009 discredited the then-governing socialists and allowed the Magyar populist to win a resounding election victory in 2010 (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2018, 1490-91).Footnote 11 In similar ways, Erdoğan in Turkey was helped by “the worst economic and financial crisis in modern Turkish history,” which depressed GDP by –6% in 2001 (Özel Reference Özel2003, 82). Both leaders then used their parliamentary majorities to suffocate democracy, sooner or later. Thus, formally legal efforts to dismantle relatively changeable institutions in parliamentary systems also depend on special circumstances, namely economic crises. Conversely, Italy’s Berlusconi, Slovakia’s Mečiar, and Czechia’s Babiš, who did not encounter such exogenous crises, did not win parliamentary majorities for their parties––and did not do grave, lasting damage to democracy.

In sum, while institutional weakness is necessary for letting populist attacks on democracy proceed, this permissive cause is not sufficient on its own. Instead, liberal pluralism “dies” only if the different types of institutional weakness intersect with specific conjunctural opportunities that provide populist leaders with the levels of mass support necessary for overriding the remaining institutional obstacles.

A Comprehensive Examination of Populist Assaults on Democracy

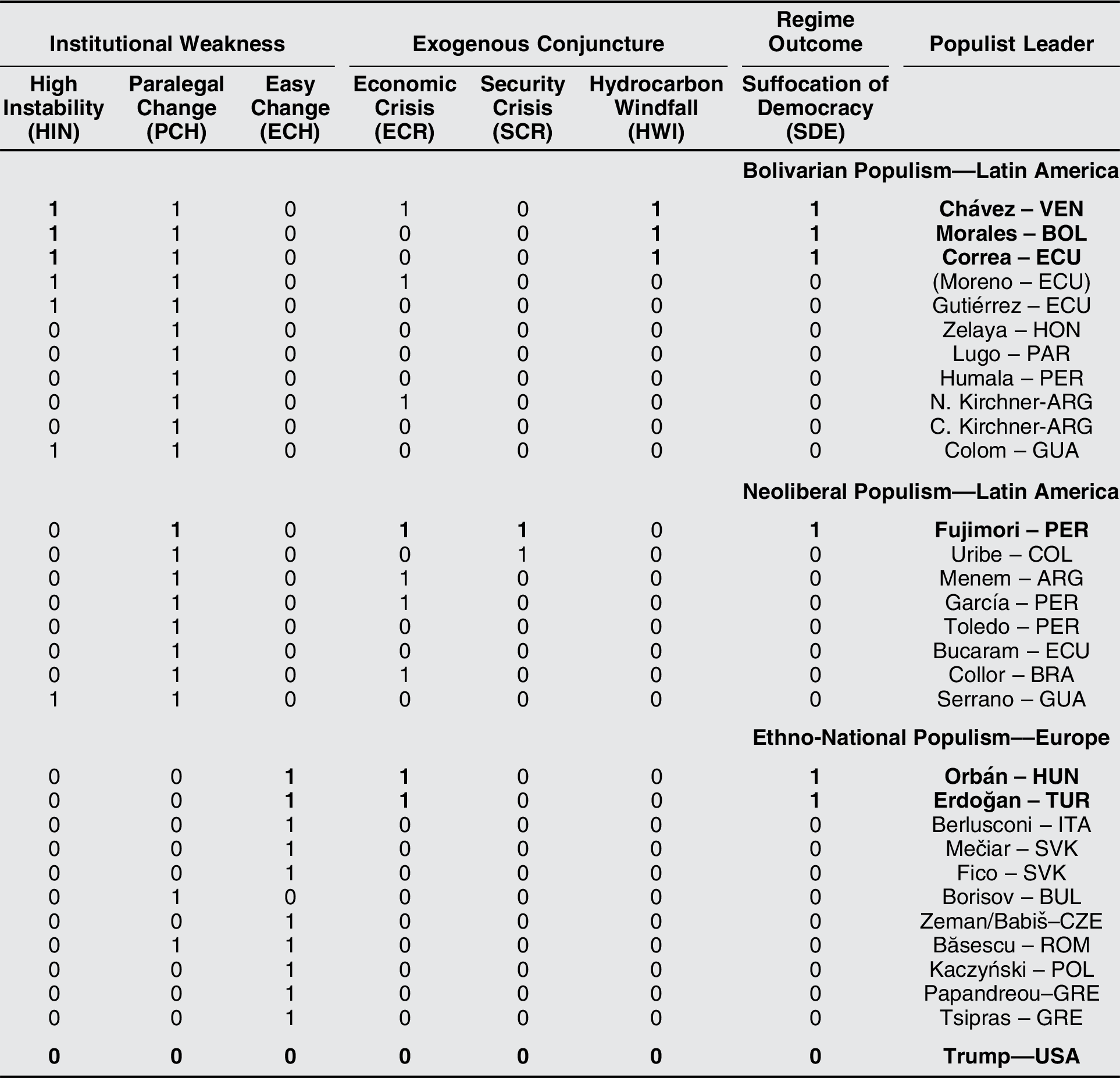

These interactive combinations of institutional debilities and exogenous opportunities align in three distinct paths of populist strangulation of democracy. Because, in their opportunistic efforts to establish political hegemony, personalistic plebiscitarian leaders exploit any institutional opening and conjunctural opportunity they encounter, populist assaults on democracy do not advance in one common, general pattern, but along three different avenues. The systematic scoring of populist experiences in Latin America and Europe summarizes these inductive findings and shows the three paths in table 1 (the online appendix explains the specific measures).

Table 1 Conditions for the suffocation of democracy by populist leaders

As regards institutional weakness, sections four and five (on openness to institutional change and on the para-legal imposition of change) have distinguished three types (listed in the three left columns of table 1), namely:

1. high instability (HIN), as in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela;

2. susceptibility to para-legal change (PCH), as in many presidential systems in Latin America; and

3. comparatively easy changeability (ECH) in European parliamentarism.

As for conjunctural opportunities, the three types discussed in section six (listed in the three middle columns of table 1) are:

1. huge hydrocarbon windfalls (HWI);

2. the coincidence of economic crisis (ECR) and security crisis (SCR); and

3. economic crisis (ECR).

In contemporary Latin America and Europe, these two sets of factors align to form three narrow paths toward the populist strangulation of democracy. The three deleterious combinations are:

1. Hydrocarbon windfalls (HWI) in presidential systems suffering from high instability (HIN),Footnote 12 which enabled Venezuela’s Chávez, Bolivia’s Morales, and Ecuador’s Correa to move toward authoritarianism.

2. The coincidence of an antecedent economic crisis (ECR) and a security crisis (SCR) in a presidential system susceptible to the para-legal imposition of change (PCH), which allowed Peru’s Fujimori to destroy democracy.

3. Economic crisis (ECR) in parliamentary systems of comparatively easy changeability (ECH), which permitted Hungary’s Orbán and Turkey’s Erdoğan to establish undemocratic hegemony.

The following formula in Boolean notation à la Charles Ragin summarizes these inductive findings and shows the three paths toward the suffocation of democracy (SDE) by populist leaders. Ragin’s approach to medium-N analysis helps identify these different paths, which arise from populist leaders’ exploitation of different types of opportunities and which a general, statistical investigation would have difficulty capturing as clearly (Ragin Reference Ragin1987, 61-67). In this Boolean formula, logical “and” (∧) stands for a combination (intersection) of necessary conditions, while logical “or” (∨) indicates the three different paths: each of these three combinations is sufficient for producing the SDE outcome.

$$\scale 81%{\rm{SDE = \left( {HWI \wedge HIN} \right) \vee \left( {\left\{ {ECR \wedge SCR} \right\} \wedge PCH} \right) \vee \left( {ECR \wedge ECH})$$

$$\scale 81%{\rm{SDE = \left( {HWI \wedge HIN} \right) \vee \left( {\left\{ {ECR \wedge SCR} \right\} \wedge PCH} \right) \vee \left( {ECR \wedge ECH})$$

These three paths are substantively meaningful by describing, first, Latin America’s leftwing, “Bolivarian” populists; second, the region’s rightwing, neoliberal populists; and third, Europe’s mainly rightwing, ethno-nationalist populists. As stressed in section six on the crucial role of conjunctural opportunities, where institutions are particularly weak (HIN) or easy to change (ECH), one exogenous factor––a hydrocarbon windfall (HWI) or an antecedent economic crisis (ECR), respectively––allows populist leaders to smother democracy. By contrast, where institutions have somewhat greater resilience (PCH; yet not HIN), only the unusual coincidence of two types of crisis, namely grave challenges to the economy as well as to public safety (ECR ∧ SCR), predicts a populist descent into authoritarianism. Moreover, the three paths are also theoretically meaningful in capturing the deleterious impact of the resource curse (HWI ∧ HIN) and the long-noted effect of crises, which depends on institutions’ openness to formal-legal change––higher in ECH than in PCH.

As the scoring of populist governing experiences in table 1 shows, only these three combinations of conditions led to the destruction of democracy; under other permutations, liberal pluralism survived in many countries. Thus, in the numerous cases where institutional weakness did not coincide with a specific conjunctural opportunity, democracy proved resilient to the illiberal and authoritarian machinations of populist leaders or recovered fully after some temporary deterioration.

The main finding of this analysis concerns the very mixed record of populist assaults on liberal pluralism. Democracy does not die easily! Authoritarian involutions are not nearly as frequent as recent concerns suggest. Even in polities that suffer from some kind of institutional debility, liberal pluralism often escapes from the subversive efforts of personalistic plebiscitarian leaders. Only in the comparatively few cases in which specific conjunctural opportunities enable populist chief executives to exploit distinct institutional weaknesses can these leaders suffocate democracy and cement their authoritarian predominance.

This wide-ranging comparative analysis thus offers reassurance. The dire warnings about populism’s threat to liberal democracy seem to overestimate the risk. Observers are overly impressed by the emblematic cases in which populist leaders managed to asphyxiate democracy; the many instances in which such efforts failed draw much less attention. The disproportionate salience commonly attributed to negative news has skewed assessments of populism’s regime impact. For understandable, yet methodologically problematic reasons, personalistic plebiscitarian leaders who destroy democracy stand out much more than authoritarian projects that are abandoned, quickly defeated, or soon reversed. The antidemocratic triumphs of Fujimori, Chávez, and Orbán are cognitively “available,” whereas the similar, yet blocked or aborted efforts of Serrano, Gutiérrez, and Mečiar are largely forgotten. This unconscious selection effect, a form of the dreaded “selection on the dependent variable,” inspires excessive anxiety, which is not justified by the actual empirical scoreboard.

Prospects for U.S. Democracy in the Global Wave of Populism

What does the preceding comparative analysis suggest for the prospects of U.S. democracy under President Trump, the first populist in the White House in 180 years? Because this personalistic, plebiscitarian leader has clear autocratic tendencies and has shown deliberate disrespect for liberal tolerance and pluralist civility, there certainly are reasons for concern. After all, two-fifths of the U.S. population have maintained strong loyalty to the willful president despite his violations of longstanding norms. Depending on his own political savvy and the Democratic opposition’s, Trump may therefore win reelection. Consequently, can the headstrong populist do lasting damage to U.S. democracy, as many observers warn (Dionne, Ornstein, and Mann Reference Dionne, Ornstein and Mann2017; Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Mounk Reference Mounk2018; Sunstein Reference Sunstein2018)?

My comparative investigation suggests that fears of an authoritarian turn in the United States may be exaggerated, as the bottom row of table 1 indicates. It seems unlikely that Trump could undermine democracy (Madrid and Weyland Reference Madrid and Weyland2019). The United States’ great institutional stability (HIN = 0) helps block populist sneak attacks. The checks and balances system and the stringent requirements for constitutional amendments hinder democracy’s dismantling through formal/legal channels (ECH = 0). Moreover, efforts to override formal rules and para-legally impose change are likely to fail (PCH = 0). The litigiousness of political forces and a vibrant civil society expose infringements to immediate judicial challenges, and the continuing strength and deep polarization of the two-party system limit Trump’s popular support and guarantee intense opposition.Footnote 13

As regards the exogenous conjunctures that allowed some populist leaders to override institutional constraints, Trump did not encounter the golden opportunity provided by an acute yet resolvable crisis; unlike Fujimori, and unlike Orbán and Erdoğan, he cannot win overwhelming popular backing and push through constitutional overhauls (ECR, SCR = 0). Nor has the U.S. president benefited from a hydrocarbon boom, which exposed Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador to the resource curse (HWI = 0). As none of the risk factors unearthed by the comparative analysis prevail in the United States, democracy seems safe (SDE = 0).

By contrast to the countries where liberal pluralism succumbed to populist attacks, the United States is a paragon of institutional strength, as the survival of a sanctified constitution for more than 230 years—a unique feat in world history—and the limited number of constitutional amendments show. Democracy’s resilience rests in part on this normative “veneration” (Elkins, Ginsburg, and Melton Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2009, 20-21, 29, 65).

Liberal pluralism also gains sustenance from the clear, strong interests of a wide range of political groupings, partisan forces, and societal sectors. While Trump’s most fervent followers show firm devotion to their outspoken leader and may go along with infringements, his core base constitutes a clear minority. Even Republican politicians keep their distance from this volatile, unpredictable leader and offer little support for truly undemocratic initiatives. Democrats and many centrists abhor Trump’s populism. Due to the institutional strength of U.S. democracy, opposition forces direct most of their energies toward formal-institutional channels, especially the electoral arena, as the exceptional participation in the 2018 midterm elections shows. Thus, most of Trump’s adversaries have avoided the populist trap, refusing to respond to his provocations in kind. They have refrained from confronting his confrontational tactics with open contention, such as rowdy protests, political mass strikes, or civil disobedienceFootnote 14––which would only play into Trump’s efforts to boost his core support by denigrating his opponents as dangerous troublemakers.

The Likely Resilience of U.S. Democracy

With its strict separation of powers and high hurdles to constitutional reform, the United States ranks low on changeability (ECH = 0). The intricate system of checks and balances, which requires cooperation and compromise among different veto players for significant change to pass, protects democratic rules against populist efforts at curtailment (Madrid and Weyland Reference Madrid and Weyland2019, 158-63). While party polarization has caused some erosion in these institutional constraints, such as the filibuster’s suspension in Senate appointment processes, it has intensified the political motivation for all groupings to use their institutional attributions to the maximum, causing worsening gridlock in this evenly divided polity (Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz2013). The prevalence of “insecure majorities” (Lee Reference Lee2016) and “unstable majorities” (Fiorina Reference Fiorina2017) has exacerbated obstruction and conflict in the increasingly “dysfunctional Congress” (Binder Reference Binder2015), aggravating “political stalemate” (Fiorina Reference Fiorina2017). As political scientists’ calls for strengthening the presidency suggest (Howell and Moe Reference Howell and Moe2016), and as Trump’s meager legislative record confirms (Nelson Reference Nelson2018, 82, 100, 148; Lee Reference Lee2018), the main problem plaguing U.S. democracy is not excessive openness to change, but “high-energy stasis” (Foley Reference Foley2013, 354) with great difficulty of passing any reforms.

Among written constitutions, the U.S. charter is by far the oldest. With its demanding, cumbersome amendment process, which requires approval by three-quarters of states, it is one of the most difficult to change (Lutz Reference Lutz1994, 362-64; Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999, 220-22; Elkins, Ginsburg, and Melton Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2009, 101, 162). Moreover, its susceptibility to reinterpretation is constrained by the inertial force of judicial precedent. The U.S. Constitution’s rigidity diverges from the relative flexibility of Hungary’s charter (Lorenz Reference Lorenz2005, 358-59), which Orbán revamped quickly. It precludes democracy’s dismantling in formally legal ways (ECH = 0). After all, while populist attacks on democracy can start with ordinary legislation, they make real headway only through constitutional overhauls. But a package of illiberal amendments or the convocation of a constituent assembly that would promote an authoritarian involution is hard to imagine in the United States.

Could populist Trump, frustrated by this dense web of institutional obstacles, simply override these constraints, arrogate power, and coercively impose illiberal and eventually authoritarian transformations, as some personalistic plebiscitarian leaders in Latin America did? The political cost and risk of such a para-legal scheme, which holds significant danger even in Latin America’s institutionally weaker settings, would be prohibitive in the United States. A wide range of politicians in Congress, at the state level, and even some in the president’s own party would resist having their influence abridged; courts would insist on upholding the law; and numerous civil-society groupings would defend their interests, needs, and causes. Thus, para-legal efforts to impose undemocratic change would provoke a huge backlash from liberal pluralism’s many stakeholders (PCH = 0).

Even in polities at middling levels of institutionalization, such assaults advanced only under conditions of severe double crisis (ECR ∧ SCR). Yet when President Trump was inaugurated, the United States was not suffering from acute grave challenges (ECR = 0, SCR = 0).Footnote 15 My comparative analysis suggests what a serious limitation this absence of crisis created for Trump—something the standard logic of American Politics misses. Presidency specialist Michael Nelson (2018, 1, 31), for instance, stresses how “fortunate” Trump was in not facing an economic or political crisis. But from the logic of populism, this was a disadvantage. After all, antecedent crises can offer a unique opportunity for a profound institutional overhaul. Foreclosing this opportunity, the favorable economic conditions under which the real estate tycoon assumed office prevented him from winning the overwhelming support that allowed Peru’s Fujimori to gain political predominance and dismantle democracy (Madrid and Weyland Reference Madrid and Weyland2019, 171-74).

This fortunate lack of crisis was no accident. In general, advanced industrialized countries like the United States are less exposed to economic shocks than economically weaker Latin America and Eastern Europe; and their higher borrowing capacity can smooth out downturns (Wibbels Reference Wibbels2006, 443-452). Remarkably, even the global crisis of 2008, which originated in the United States, hurt this country significantly less (-2.9% growth in 2009) than Hungary (-6.6%), for instance. Other grave challenges, such as large-scale attacks by foreign terrorists, are unlikely in the United States as well; 9/11 was the first strike on the U.S. mainland in nearly 200 years and has not been followed by similar assaults. And what country in the world would dare to defy the global superpower by declaring war? Conversely, a war started by notorious hothead Trump may not produce a significant, lasting “rally around the flag” effect, but instead fuel criticism and conflict in this highly polarized society. For these reasons, the chances for the U.S. leader to win the overwhelming mass support that allowed some populist chief executives in Latin America and Eastern Europe to sweep away liberal safeguards, concentrate power, and march toward authoritarianism seem low.

Even if some accidental crisis were to boost Trump’s approval ratings, democratic backsliding would be unlikely in the United States. After all, the vigilance of a well-organized, resource-endowed civil society and the litigiousness of the citizenry, which has ample opportunities to invoke diffuse judicial review, sustain compliance with formal institutions and block or limit efforts to override constitutional rules. Populist attempts to grab power, weaken checks and balances, restrict freedom of the press, and squeeze the opposition run into a web of obstacles and incur substantial political costs in this evenly divided polity. All of Trump’s controversial policy measures that have threatened to damage liberal democracy have immediately provoked a withering barrage of court challenges, initiated by a great variety of citizens, NGOs, state-level agencies, and city governments; and interestingly, Trump has been unusually respectful of judicial rulings (Peabody Reference Peabody2018). In line with voter preferences, many cities and states have also used administrative mechanisms to hinder the billionaire’s populist initiatives (Whittington Reference Whittington2018, 4), for instance by refusing to cooperate with his attempts at tightening immigration enforcement (“sanctuary cities”).

Thus, societal organizations, voter groupings, and their elected representatives—including Republicans (Nelson Reference Nelson2018, 9, 50, 85-89, 140; Lee Reference Lee2018, 1-8; Woodward Reference Woodward2018, 206, 215, 317, 320-21)—have used all institutional arenas in the United States’ federal system of checks and balances, with its multiple access points for veto players, to contain the headstrong populist. Remarkably, even Trump appointees and close aides have deliberately sabotaged his initiatives (Anonymous 2018; Woodward Reference Woodward2018, xviii-xxii, 141-43, 147, 158, 163). This multi-faceted, determined resistance has foreclosed a breach in the institutional framework of liberal democracy and has made attempts to break existing rules and push through a para-legal overhaul virtually unthinkable. Not even Trump’s tweet storms have mentioned the idea of convoking a constituent assembly––the main mechanism through which some populist leaders have leveraged their plebiscitarian mass acclamation for dismantling democracy.

The mass support for the values of liberal pluralism (recent data in Drutman Reference Drutman2018), rooted in the United States’ definition of national identity (Huntington Reference Huntington1981, chap. 2), provides a solid foundation for widespread aversion to the transgressive populist in the White House. Even more deeply entrenched, the self-interests and political commitments of citizens and politicians drive this alertness to potential violations and the determination to prevent infringements. Longstanding democratic experience and high levels of education and political sophistication have made many people, social movements, and party leaders aware of the stakes of institutional changes (cf. Przeworski forthcoming, 109). They understand the political repercussions, policy impact, and distributional consequences of even seemingly minor technical measures, such as voter ID laws.

Interests thus provide the fundamental base of sustenance for liberal pluralism in the United States. As Weber (1976, 15) highlighted, interests constitute a more solid foundation for action than norms and values. A vigilant, active citizenry and a vibrant civil society reliably sustain U.S. democracy. The country’s constitutional system continues to be reasonably successful in fulfilling its main purpose, namely to prevent the abuse of the government’s coercive power by submitting personalistic will to institutional constraints and by ensuring the rule of law. The inherent limitations that the web of checks and balances in a federal system imposes on populist leadership have a firm base.

For these reasons, the concerns and fears that President Trump’s illiberal rhetoric and autocratic leanings have evoked are unlikely to come true. U.S. democracy will probably survive this bout of populism (SDE = 0).

Unintended Consequences of Trump’s Populism: Democratic Mobilization and Re-Equilibration?

Precisely because it poses a potential threat to liberal pluralism, President Trump’s populism has provoked a powerful allergic reaction, which has started to revitalize and energize the United States’ longstanding yet exhausted democracy. The president’s flagrant violations of liberal norms and transgressive institutional efforts have stimulated intense and widespread counter-mobilization. For many years, Americanists complained about political apathy; electoral participation, for instance, is significantly lower than across the advanced industrial world. Even fierce partisan competition did not prompt great mobilizational efforts because party elites feared that drawing additional population sectors into the electoral arena could weaken their own position (Ginsberg and Shefter Reference Ginsberg and Shefter2002, 43-45).

But the electoral victory of a strong-willed populist upended this low-level equilibrium. By mobilizing a fervent mass base on the ideological right, Trump has induced ample sectors on the left and center to join the fray as well. Groups that his insults and attacks have disparaged have been especially motivated (Putnam and Skocpol Reference Putnam and Skocpol2018). Inadvertently, the transgressor-in-chief has given a strong boost to political participation; he may even have prompted a reassertion of democratic values (Drutman Reference Drutman2018, 1). While his resentful electoral appeals, intemperate pronouncements, and ill-prepared policy measures have exacerbated polarization and further hindered democratic deliberation of crucial issues that the United States has long failed to resolve, such as the dysfunctional immigration system, his populism has also had the beneficial effect of stimulating “resistance” of various kinds. Given the innumerable access points that the institutionally strong framework of liberal democracy offers, this bottom-up energy has predominantly found expression through regular institutional and electoral outlets––and has thus strengthened these institutions (Putnam and Skocpol Reference Putnam and Skocpol2018, 8, 11).

This positive backlash dynamic became obvious in the midterm elections of November 2018. The Democratic Party benefited from a striking emergence of new candidates, disproportionately women and minorities. High-profile campaigns, such as “Beto” O’Rourke in Texas, elicited enormous excitement, nation-wide attention, and massive donations of time and money. These intense mobilizational efforts, which contributed to an unusually high midterm turnout not witnessed since 1914, gave the Democrats the biggest seat gains in the House of Representatives since the times of another transgressive president, namely right after Richard Nixon’s resignation in the Watergate scandal (1974). Certainly, however, Trump’s confrontational counter-mobilization (“the migrant caravan”) energized his core constituency, limited the impact of this “blue wave,” and helped the Republicans strengthen their Senate majority.

By awarding the opposition control over one house of Congress, this constructive response to Trump’s populism has reinforced checks and balances and perhaps initiated a move toward democratic re-equilibration (see Linz Reference Linz1978, 87-90). Contrary to the fears of historical institutionalists, who in their linear way of thinking (“path dependency”) tend to extrapolate current trends into the future and therefore predict continuing deterioration, democratic pluralism can unleash powerful forces for recovery (Madrid and Weyland Reference Madrid and Weyland2019, 181-83). Through its participatory opportunities and competitive mechanisms, liberal democracy in an institutionally strong setting mobilizes and channels the energies of active citizens and civil society organizations into a pro-democratic upsurge. Problems therefore do not necessarily persist and worsen; instead, they can unleash efforts at repair and renewal. When decline stimulates counterforces, political development can have cyclical turnarounds. Precisely by threatening to undermine liberal democracy, Trump’s populism may unintentionally—through its deterrent effects—end up strengthening this rusty system and fuel attempts to ameliorate its many problems (on those, see Lieberman et al. Reference Lieberman, Mettler, Pepinsky, Roberts and Valelly2019).

Conclusion

This comparative investigation shows that populism’s threat to democracy depends on a polity’s institutional strength. Therefore, this danger is distinctly limited in advanced industrialized countries, especially the United States with its firm checks and balances. Even in the weaker institutional settings of Eastern Europe and Latin America, personalistic leaders sustained by plebiscitarian mass support do not have free rein. Because efforts at authoritarian transformation encounter obstacles and provoke opposition, they succeed only under special conditions: when severe crises offer an unusual opportunity for establishing heroic leadership; or when huge windfalls “buy” massive support. Many populist attempts to suffocate democracy fail. Recent writings on democratic backsliding do not sufficiently consider this mixed record; their fears are derived too much from the few outstanding cases of populist “success.” This literature highlights deleterious possibilities. But the probability of undemocratic outcomes is limited, and low in institutionally strong polities.

To rectify this imbalance, my wide-ranging investigation examined under what conditions populist assaults on democracy achieve their goals––and when not. This analysis demonstrates that populist paths toward authoritarianism are narrow and uncertain: Only when specific institutional weaknesses coincide with extraordinary, largely exogenous conjunctures can populist leaders destroy democracy. Consequently, authoritarian backsliding in the United States with its firm institutionalization is unlikely. Notorious gridlock in Congress and a rigid, age-old constitution impede the formally legal dismantling of democracy that Hungary’s Orbán engineered. And the participatory energy of citizens, the litigious activism of civil society, and the intensity of partisan competition contain rule violations and prevent the para-legal transformations that abolished democracy in Peru, Turkey, and Venezuela.

The populist in the White House has encountered a dense web of institutional constraints and has seen most of his attacks on liberal rules and principles blunted and blocked. President Trump lacks the political strength to override these obstacles and forcefully push toward democratic involution. Neither in 2016 nor 2018 did he and his party win a plurality of the popular vote, not to speak of the massive majorities that gave Fujimori, Chávez, and Orbán unchallengeable popular mandates. The absence of an acute crisis that Trump could have resolved upon taking office prevented the U.S. populist from garnering the overwhelming support that enabled some––though few––of his counterparts in Europe and Latin America to advance resolutely toward authoritarian rule.

In sum, the man from the golden tower has faced an iron cage of institutional impediments and lacked the golden opportunity to strip away these restrictions. Therefore, Trump cannot follow the populist script, establish his supra-institutional predominance, and suffocate liberal pluralism. Comparative analysis suggests that in the United States, especially, “democracy trumps populism” (Weyland and Madrid Reference Weyland and Madrid2019).

Trump’s opponents need to absorb this reassuring conclusion in order not to respond to his populist provocations with equally hostile countermeasures, such as fierce, contentious resistance to “fascism,” a striking mischaracterization of the recent crop of non-ideological, largely non-violent right-wing populists (Eatwell and Goodwin Reference Eatwell and Goodwin2018, 47-48, 64-67). With their confrontational tactics, populist leaders deliberately tempt their adversaries to join the mud wrestling. But nobody emerges unsullied from such a nasty contest. Shrill counterattacks backfire and discredit the opposition. Given the United States’ institutional strength, the much more promising path is calm, systematic, patient usage of the regular checks and balances to contain the enfant terrible in the White House—and active, widespread electoral participation to defeat him in 2020.

Supplementary Materials

Cases, Measures, and Scores in Table 1

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719003955