Open-pit mining is a frequent source of controversy in the Arctic and beyond. Its invasive technologies disrupt landscapes, and, in turn, irreversibly alter conditions that sustain specific ways of living. Often, these controversies unfold where indigenous ways of interacting with landscapes are already under threat. However, as Li has noted (Reference Li2013, p. 401) political responses to mining “do not simply cohere as anti-mining social movements”, but can involve multiple demands and divergent knowledge encounters that do not have to be based on a common understanding of the world.

This article concerns extractivism in the making in an area that is already contested and marginalised, fraught with a colonial legacy that is, in some ways, still ongoing (Joks, Østmo, & Law, Reference Joks, Østmo and Law2020; Law & Joks Reference Law and Joks2019; Ween & Lien Reference Ween and Lien2012). By extractivism, I refer to processes by which industrial corporations undertake large-scale and irreversible extraction or removal of non-renewable inorganic matter, such minerals, coal, or oil. Extractivism denotes not only the material processes of extraction, but the ideology and the conceptual apparatus that supports this practice, which often involves a naturalisation of resources as there for taking (see, e.g. Hastrup & Lien, Reference Hastrup and Lien2020; Richardson & Weslkalnys, Reference Richardson and Weszkalnys2014).

Tracing the uneven unfolding of a possible future, a rumour, a prospect, or an interruption, I pay attention to the fragmented nature and affective dimensions of resource extractivism as it thickens around a proposed expansion of a quartzite quarry on the Varanger Peninsula, in Finnmark county, North Norway. I approach this quarry and the controversy that currently unfolds around the mountain Giemaš as an occasion for mustering various manifestations of the real. The article is also an experiment in ethnographic writing that explores multiple epistemic authorities (Brattland, Kramvig, & Verran, Reference Brattland, Kramvig and Verran2018).

I have chosen to write about Giemaš as an autoethnographic journey, sketching a process of knowing based on many different and somewhat contingent encounters. But the word journey is misleading, because rather than a journey with a beginning and an end, the encounters I describe are mostly unplanned, fluid, uneven, and still ongoing (negotiations take place as I revise this article in 2020).

I also draw on stories of other people’s encounters, but approach these as ethnographic moments in their own right, because it is precisely through such retelling of stories that the realities unfold. This approach is informed by current explorations of Sámi ways of knowing, and by material semiotics and anthropology. I draw on the idea that the real is not given in the order of things, but enacted, cultivated, or even forgotten in socio-material practices, hence it is multiple (see, e.g. Mol, Reference Mol2002). Just as there are many practices, there are many “reals”, some of which are systematically made absent (Law, Reference Law2004, p.161). In ethnographic practice, we are taking part in the enactment of partially overlapping propositions about the real. This means that any statement about the real is also political (Mol, Reference Mol2002), and, as I shall detail below, that ontological politics can be a risky affair. Furthermore, I draw on Joks et al. (Reference Joks, Østmo and Law2020) account of how Sámi practices allow relational and fluid ways of knowing, that defy common European binaries between nature and culture, or between the knower and the known. Rather than offering a coherent and fixed account about the ongoing controversy around Giemaš, I present an ethnographic travelogue, or a “pluriversal storytelling” that seeks to expand the space for different ontologies to enter academic discourse (de la Cadena & Blaser, Reference De la Cadena and Blaser2018; Guttorm, Kantonen, & Kramvig, Reference Guttorm, Kantonen and Kramvig2020, p. 149). Hence, I am attentive to subtle claims about relations, even those that defy the hegemonic dualism separating living bios from a presumed non-living geo (Lyons, Reference Lyons2020).

A distinct formation along the road

I’d always noticed the mountain for its distinct layers, tilting in the evening sun, like an upright sandwich, as if swaying, falling, and then it froze. But I’d never really seen its eastern slope, a sand-coloured meshwork of roads gnawing on its interior, not until that summer. Giemaš amongst Sámi speakers, I never even knew it had a name. Nobody told me, and I guess I never asked.

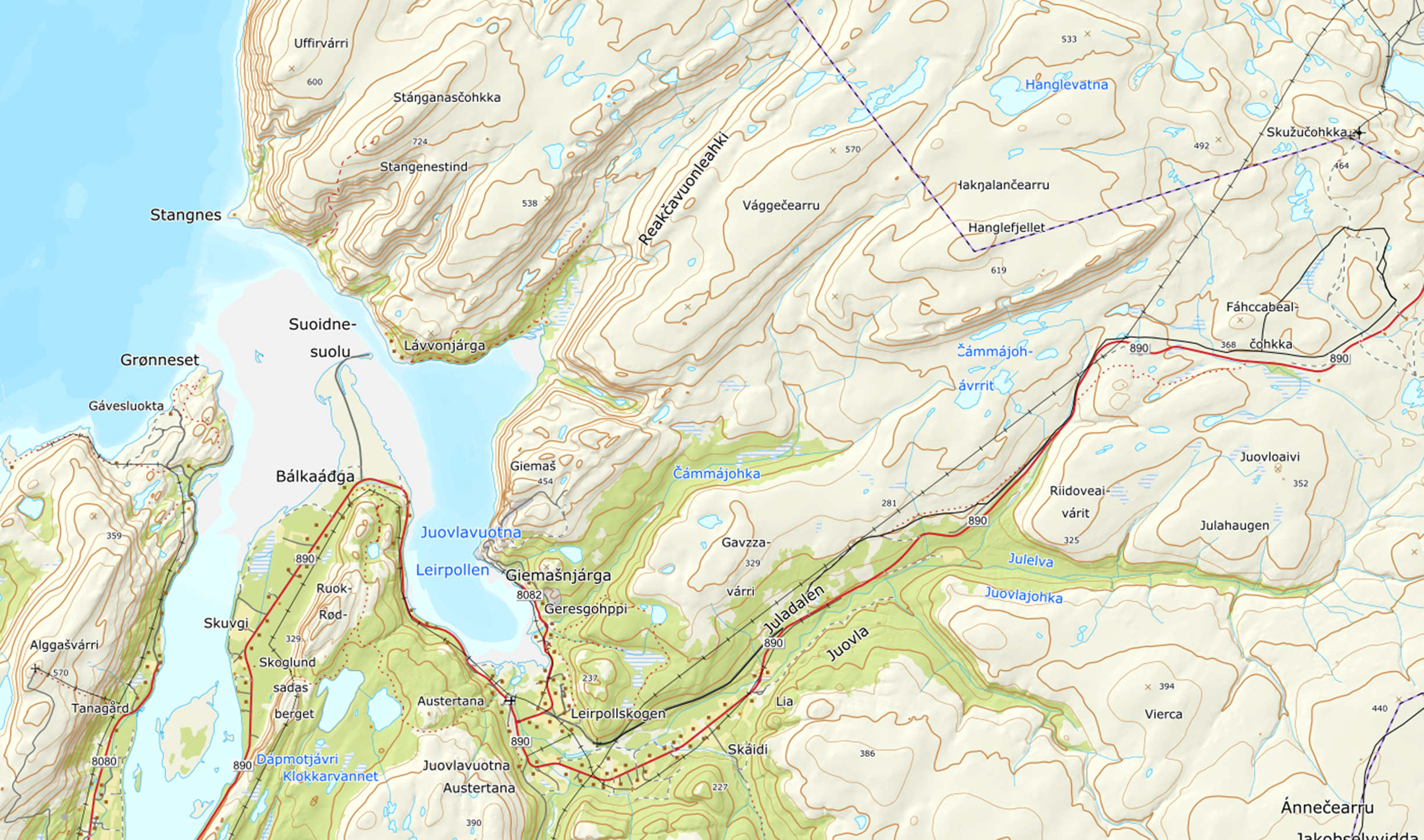

The mountain is easily remembered, as its steep layered shape forms a significant part of the scenery as you take the road, from the river Deatnu (Tana) and north across the Varanger Peninsula, towards the coast of the Barents Sea (see Fig. 1). Nested between the peninsula and the brackish river, it marks a steep transition between wetlands to the south and the mountain plateau to the North. For some, this is only a familiar sight along the road where the mountain drops steeply into the water below. For others, it is a place to make a living, as the river branches off to a narrow sound; a lively place for fishing, and the outskirts of a reindeer pasture needed along their route of seasonal migration. The quarry is situated in Juovlavuotna (Austertana), a village settlement of less than 200 inhabitants near the Deatnu river (see Ween, this issue). Deatnu/ Tana is the name of the river, as well as the municipality that encompasses the quartzite quarry (see Fig. 2).

The site of this controversy is about an hour’s drive from the Barents coast, where I have done fieldwork for decades (e.g. Lien, Reference Lien2020; Ween & Lien, 2012; Reference Ween, Lien, Head, Saltzman, Selten and Stenseke2017). Yet, even if quartzite has been extracted from this mountain for decades, I was not aware of these operations, and it was not a topic that drew a lot of attention. Not until 2016.

First encounters

Late evening sun is in my eyes as I am driving North. I pass Stjernevann (Nástejávri), a lake on the mountain plateau between Juovlavuotna and Båtsfjord, where the head of the reindeer siida in this region has his summer camp. Smoke comes out of his lavvo. I park the car, hoping to be able to go through some field notes from a previous visit. August is the time for marking the calves before the reindeer move towards their autumn pastures. With around four thousand animals, this siida is busy for several weeks. I had spent the day before watching them mark calves in the reindeer corrals. But today my interlocutor, Frode, who has just finished a day’s work wants to relax in the sun, and look after the fire.

- Don’t go inside, he says, you’ll smell of smoke afterwards!

Frode adds salix to the fire, says it makes the meat turn red. Says it’s the same calf I saw in the corral yesterday, wounded. I can taste it tomorrow. But now he wants to talk about something else. Frode tells me he is worried. It is about the quartzite quarry. It interrupts his sleep, he finds himself awake at night pondering what to do. Briefly, as we sit by the lavvo, he shares his concerns. I learn that there is a quartzite quarry in Juovlavuotna, it has been there for more than forty years, owned by a well-known company called Elkem. A few years ago, Elkem was bought by Chinese investors, and with new owners, they plan to expand. They claim that the quartzite available in the current open quarry will only last a few more years, so to secure a continuation of the quarry, they need to open up a vast new area for quartzite extraction. The planned expansion will bring the quartzite quarry right next to the area where the reindeer gather now, near the boundaries of the fenced area known as “the grazing garden”. Reindeer graze on non-domesticated plants, and move freely most of the time. The grazing garden is where they are gathered in late summer, while calves are marked and tagged. It is a vast area, and needs to be, in order to provide enough to eat for the reindeer for however long it takes before they can pass on to the autumn pastures, and then, a couple of months later, towards the sound where they can cross the Deatnu river to reach their winter pastures further south.

Frode details how the planned expansion of the quarry will create difficulties for the whole operation of sorting, grazing, and migration. This is what concerns him, and there is no doubt that he must try to prevent this, if he can. But preventing the expansion is also difficult in relation to kin, some who struggle to make a living locally in a village with few jobs available. These are people who are keen to hold on to whatever jobs there are, people who have lost touch more or less, he says, with reindeer herding as a subsistence practice. He worries that kin will be taking sides against one another, which is another way in which the quarry interrupts.

On the Varanger Peninsula, where coastal Sámi constitutes the majority of Sámi descendants, more than 13,000 reindeer migrate to the peninsula in spring, hence the Sámi siida depend on this area. A siida, also referred to as a reindeer herding assemblage, includes relatives of all ages, reindeer, and the affordances of the landscape that the reindeer graze upon, and where people can find materials and immaterial connectedness that is part of the reindeer herding practice (Sara, Reference Sara2011). Although Sámi practices are often associated with reindeer herding, many Sámi speakers, as well as descendants of Sámi speakers, never specialised in reindeer herding in the first place. Instead, they relied on small-scale farming and fishing, much the same way as the Norwegian-speaking inhabiting the coast. In spite of a revitalisation of Sámi identity and significant (Lien, Reference Lien2020) political shifts (see below), their situation is marked by the legacy of 20th-century state policies of assimilation and colonisation. Sámi descendants who are now in their 50s or older were often encouraged to speak Norwegian at home, as well as at school. Hence, for a significant part of the local population on mixed Sámi descent, the Sámi language was lost.

Fig. 1. View of the Giemaš from road 890, across the sound. The quartz quarry is clearly visible on the mountain slope descending on the right.

Photo by the author.

Fig. 2. Map Austertana/Juovlavuotna and Giemaš.

©kartverket/norgeskart.no.

Uncanny stones and broken stories

Driving back from the lake, I recall snippets of other conversations when the same quartzite quarry came up. One elderly woman had mentioned an incident in 1973 when they shot dynamite near Giemaš. A huge rock came rolling down, and buried the foundation of the crushing plant. Old folks said that that they should not have been doing this so close to the sieidi. I suddenly recall how the woman looked at me as if to make sure I understood that this was not about the risk of using too much dynamite. It was the sieidi itself that interrupted the planned construction of the quarry.

During the following weeks, the mountain’s presence in my field notes expanded. I learned that its name was Giemaš, and the next time I passed it with a friend from a coastal village, we drove as far as we could in the direction of the quarry. A short walk from the nearest parking lot we explored the huge hollow pit, as if a giant creature had taken a bite of the landscape. We saw the idle heavy machinery up close, and gravel roads that crisscrossed the greater part of the slope facing East. So this was the quartzite quarry: so hidden from plain sight for those who stay on the main road, and so much bigger than we thought.

A few days earlier, the issue of the quartzite quarry had come up again. My friend shared that she had heard that once there was an accident, a large boulder had come down and fallen into the water. She had heard it said that an old Sámi man had predicted that it would happen. But she did not know much about it and suggested that I speak with someone else, – perhaps Frode would know?

These conversations were my first encounters in this region that enacted sieidi as a relational force in the present, and agential entity that could potentially interfere in the course of the events. Sieidi is well-known figures of Sámi religion. Known as Sámi sacrificial stones, they are found in many places in Northern Scandinavia. Many are forgotten, but quite a few remain as remnants of a time when the earth was alive with forces that exceed ontological assumptions that constitute the real in common public discourse. Often classified as “heritage”, these stones are, however, more than relics of the past. Based on maps, as well as written and oral sources Myrvoll (Reference Myrvoll, Heinämäki and Herrmann2017) has identified more than twenty in the inland region of Troms and Nordland counties. Tracing memories through explorative engagements Kramvig and Verran (Reference Kramvig, Verran, Henriksen, Hydle and Kramvig2020) have described what we might tentatively think of as a reacknowledgement, or even revival of some such stones, while Reinert (Reference Reinert2016) recounts stories of a sieidi’s revenge when obligations of respect were not done properly in connection with the building of a new road near the town Hammerfest in the 1950s. According to this story, the chief engineer intended to blow up the stone to make way for the planned new road, but died in a brutal traffic accident. An old saying that “whoever blows me up will lose his head” was thus confirmed, and the road itself was placed further inland (Reinert, Reference Reinert2016, pp. 98–99). More recently, the significance of other-than-human relations has become relevant in controversies around a planned copper mine in the same area, called Nussir (see also Dannevig & Dale, Reference Dannevig, Dale, Dale, Bay-Larsen and Skorstad2018). As Reinert puts it, the sieidi occupies both human and non-human timescales:

“echoing a time before Christianity and colonization, foreshadowing (perhaps) remote futures beyond the human –but capable of acting, then as today, within the span of individual human lives” (Reinert, Reference Reinert2016, p. 100).

But the trajectories of the sieidi themselves have been interrupted. Broken by more than a century of harsh assimilation policies towards the Sámi population, along with a massive violence and denial in relation to what would then be seen as “indigenous” or “heathen” belief, their presence in the landscape is unclear, concealed, and for a large part forgotten (Oskal, Ijäs, & Bjørklund, Reference Oskal, Ijäs and Bjørklund2019).

Secular lutheranism and indigenous cosmopolitcs

The Varanger Peninsula bears little resemblance to the Andean worlds described in accounts of cosmopolitics in relation to other-than-human presences evoked as part of mining controversies, such as for instance those described by de la Cadena (Reference De la Cadena2015) and Li (Reference Li2013). Yet, the association between sacred rocks and indigeneity is a potent one. The attribution of agency to seemingly inert materials such as rocks is no small matter (Povinelli, Reference Povinelli1995). As Kristina Lyons reminds us, this has been “the grounds on which to dehumanize colonized and enslaved peoples for their so-called pre-modern mentalities” (Lyons, Reference Lyons2020, p. 42). My interlocutors in North Norway are rather cautious about evoking what might be thought of as superstition, and so am I. Inculcated in a “modern” way of perceiving the world, we have learned that matter is essentially inert, and that alluding to anything else is “‘myth’ or ‘superstition’”.

Hegemonic discourse in Norway is informed by a Lutheran Christianity (until 2012, the public religion of the nation state). Around 70% of the population belong to the Church of Norway, which still obtains financial support from the state of Norway, along with many hundreds of religious congregations that are entitled to state support, based on their membership numbers. These include a few small neo-pagan and shamanistic congregations, but the majority by far are Christian and Islamic congregations (Source: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/tema/tro-og-livssyn/tros-og-livssynssamfunn/innsiktsartikler/antall-tilskuddsberettigede-medlemmer-i-/id631507/).

Compared to most other versions of Christianity, Norway’s protestant Lutheran church is a relatively “secular” institution, with few and simple rituals and an emphasis on individualised and personal belief in Christ. Hence, there has traditionally been no room for attributing sacredness to material things, including landscapes; on the contrary, Norwegians learn to appreciate environmental surroundings through the lens of scientific realism.

While on some level, this affects Norwegian and Sámi alike, the implications are different. Christian mission and the assimilation policy in Sápmi was particularly harsh towards Sámi beliefs and religious practices. The eradication of Sámi place names on official maps further severed the connection between what Sámi scholar Marit Myrvoll calls the “connection between the visible and the invisible reality” of landscapes (Myrvoll, Reference Myrvoll, Heinämäki and Herrmann2017, p. 114). While there has been an important resurgence of shamanistic practices inspired by Sámi belief, including what may be called neo-shamanism (not least within music), often incorporating a “panindigeneous spirituality” (Kraft, Reference Kraft2010, p. 54), such practices remain fairly marginalised in many coastal communities in Varanger. Hence, it is far from evident that a self-named shaman practitioner would be recognised as such within the local community.

Furthermore, being Sámi in coastal Finnmark has been a risky choice, something that many sought to hide, or shed altogether (Eidheim, Reference Eidheim1971; Østmo & Law, Reference Østmo and Law2018). For many people, a Sámi identity was never really an option, because the deliberate shift from a Sámi to a Norwegian identity had been taken on by the previous generation. Hence, reclaiming Sáminess can be experienced as revealing family secrets, or having to choose between one side of the family and another (see Lien, Reference Lien2020; Ween & Lien, Reference Ween and Lien2012).

The recognition of Sámi as an indigenous people, and the creation of the Sámi parliament in 1989 was a late response to more than a century of colonisation of Sámi people and practices by Norwegian state authorities. The revitalisation of Sámi ethnic identity and language has made it easier for the younger generation to identify as Sámi, but has not necessarily challenged the dominance of a secular, modern logic of reasoning, especially in public discourse. Rather, it can be argued that the political efforts that curbed the most intensive assimilation were based on an idea of “equality as sameness” (Gullestad, Reference Gullestad1992) through dichomotisation and complementarisation of ethnic emblems (Eidheim, Reference Eidheim1971 p. 75). Sámi revitalisation was achieved through the establishment of numerous institutions that mimic those of the Norwegian nation (a Sámi parliament, a Sámi national day, a Sámi flag and the like), but rarely questioned the secular, scientific foundation that underpins Norwegian (and hence also Sámi) political discourse. Rather than forging ontological difference, what de la Cadena and Blaser (Reference De la Cadena and Blaser2018) refer to as the pluriverse, Sámi ways of conceptualising and practicing their world have thus not only been ignored, but are “made unintelligible and unimaginable as possibly appropriate descriptions of reality” (Østmo & Law, Reference Østmo and Law2018, p. 350).

The Varanger Peninsula was traditionally an area of mixed Norwegian and Sámi settlements where such displacement was not only forged from above, but also for a large part internalised through stigmatizsation and shame (Kramvig & Verran, Reference Kramvig, Verran, Henriksen, Hydle and Kramvig2020). It is against this background that we need to acknowledge the need to thread carefully in relation to stories of non-secular attributes of mountains, rocks, or rivers. As Britt Kramvig pointed out, reading an early version of this paper, it is after all not very long ago that people were burned as witches in this region (for details, see Willumsen, Reference Willumsen2011).

How quartzite interrupts

The planned expansion of the quartzite quarry will not only interrupt reindeer pastures. Many other practices and landscapes are at risk, including Mjelkevággi, a favoured lake for Arctic charr, and marine life (see Ween, this issue). Following Frode’s suggestion, I approached Yngve, who had recently spoken up against Elkem at a public hearing and had prepared a PowerPoint presentation, detailing numerous potential effects of the planned expansion on local livelihoods.

I met Yngve at his house in Lavvonjarg, a tiny settlement on the sound that marks the entrance to the fjord where the quartzite quarry is located. Several times a week, freight tankers literally pass by his house, fetching quartzite for further processing. Yngve picked me up with his open motorboat, from the sandy peninsula and nature reserve called “Høyholmen”. Some friends arrive while we talk, and we quickly map our shared social acquaintances while he prepares a meal of freshly boiled King crab with white bread and mayonnaise.

Aware that I might interrupt our casual dinner conversation, I told Yngve and his friends that I kept hearing stories about strange things happening around the quarry, and so I wondered, was there anything sacred about it? Yngve’s response was abrupt and cautious:

- Who told you that?

I replied that several people had alluded to such events, but hesitated to name anyone in particular, and the question was left hanging. Soon afterwards, the topic of accidents came up again in the now-familiar format: Warnings had been uttered but not taken seriously, and then something unexpected happened (a rock suddenly came down) that was both dangerous and hard to explain.

These events were obviously not included in his PowerPoint presentation. His slides detail other expected and potential impact of the planned expansion, but not in a way that would provoke epistemic disconcertment (Kramvig & Verran, Reference Kramvig, Verran, Henriksen, Hydle and Kramvig2020). Yngve’s intervention is part of a political process, and he knows the unspoken rules. As he describes the process so far, he mentions the company lies and deceit. He claims that Giemaš used to be a preferred site for migratory birds as well as grazing land for reindeer and sheep. He laments the loss of herring and haddock in the bay near his house, and thinks it is due to the heavy traffic of ships in the sound, ships that transport the quartzite to processing sites elsewhere. And he mentions that at least two people suffer from what is locally called “steinlunge”, a lung disease caused by mineral dust. All of these relations are included in his PowerPoint presentation. He describes the planned expansion of 15 km2 as equal to 1900 soccer fields. And he adds that the Norwegian state has promised to subsidise a dredging operation to improve the shipping canal. This is yet another environmental hazard, and might affect the salmon smolt, the trout and the local seal, as well as sandeel that the smolt feed upon (for details, see Ween, Reference Ween2020).

Later, I return to Frode to learn more about how this expansion matters for the reindeer herding operation. I have plugged up my computer at his kitchen table, where he serves me fried freshly smoked reindeer and coffee. Gradually he conveys an understanding that I, mindful of the fragmentary nature of my own understanding, can at least partially recapture, as follows:

During the seasonal migration to and from the peninsula, the reindeer need to cross the river Deatnu. In order to get to where they can cross, they follow a route along a valley that takes them between the current quartzite quarry and the planned area of expansion. If this valley is blocked, how will they migrate, and how will they cross the river?

Another concern is the noise associated with both opening up the new area, and extracting quartzite. This is likely to disturb the reindeers’ pattern of movement in the grazing area. (The disturbance of mining activity on reindeer habitat has recently been documented by biologists, based on a study in this area, for details, see Eftestøl, Flydal, Tsegaye, & Coleman, Reference Eftestøl, Flydal, Tsegaye and Coleman2019). If they shy away from the area near the quarry, they will most likely crowd together near the main road, and graze in a smaller patch, until there is not enough undergrowth left. With signs of overgrazing, it will appear as if there is more reindeer than his grazing territory can support, and the health of the animals could be compromised. According to publicly available reports Frode’s siida is amongst the top herding units when it comes to animal health as measured, for example, by the average size of calves at the time of slaughter. This reflects a careful balance between the number of reindeer and the pastures available. The planned expansion could disrupt this balance.

Another concern is the reindeer fence, an intricate system of corrals and corridors that allows the herders to sort, separate, and identify their animals. This arrangement requires considerable areas of pasture around it. Right at this site, there are plants that the reindeer like to eat in late summer, such as mushrooms. Because there is enough food for them while they wait, this means they are easy to work with during marking. To have to move the reindeer fence farther away from the quarry would complicate this adaptation, and be very expensive as well.

Frode’s concerns give us a glimpse into another set of trajectories than that of the quartzite quarry. He depicts a seasonal migration route that has left its subtle traces in the landscape, he details multispecies relations of domestication that are not easily noticeable for an outsider, and his concern reflects his care for a siida complex that goes back many generations, while anticipating future generations. But this, and other precolonial reindeer enterprises, are now partly under the governance of state institutions, institutions that know reindeer differently. Furthermore, various infrastructures (electricity lines, roads, windmills) have carved out the area, bit by bit, and diminished the space available for pasture (see also Benjaminsen, Eira, & Sara, Reference Benjaminsen, Eira and Sara2016; Sara, Reference Sara2011). The planned expansion is yet another interruption to the reindeer operations. Its noisy extraction will cut new wounds in the landscape, and break into the patterns of movement that have sustained reindeer and their people on this barren peninsula for more than a thousand years. But the planned expansion is also a response to another anticipated interruption: that inevitable moment inscribed in all extractive industries, that is when the resource runs out. In this way, the extractive operation is, in itself, a complex force, anticipating its own annihilation.

The politics of extractivism and the scope of the real

If natural resource exploitation is a “sustained project of abstracting substances identified as useful, valuable and natural in origin from their environment” (Richardson & Weszkalnys, Reference Richardson and Weszkalnys2014, p. 6), then that process has just taken another turn. Carefully attuned to the political and legal procedures established by the Norwegian state, it has already done the groundwork of abstraction: By anticipating and naming the various entities that may be impacted by its future operations, it has also assembled the tactics for dealing with them, whether through the form of the due political process, through sidelining them (as marginal or irrelevant) or through financial compensation. In this way, it has already defined the scope of the real, and the scope of anticipated harm. The logic of Norwegian resource capitalism functions within the coordinates of the modern contract. Reinert (Reference Reinert2016, p. 96) writes:

If extractive resource capitalism is a sort of ontological machine – an engine that continuously remakes the world and its entities as already-given, in ways that facilitate surplus value extraction – then it is all the more vital to question the paradigms that subtend it and produce not just nonhuman life but also nonlife as domains of control, use, modification, and productive investment.

What if harm exceeds the domain of an impact assessment? Or more precisely, following Reinert’s proposal to treat harm as a matter for ontological exploration: “What beings exist, such that they can be harmed”? (ibid: 97). And how might they make themselves known?

In her account of a proposed mining enterprise in Northern Peru, Fabiana Li describes how knowledge encounters involved not only environmental dimensions of the landscape, (plants and animals) but also “unexpected forms of life” such as “Apus and other earth beings that animate the Andean landscape” (Li, Reference Li2013, p. 400). She makes it clear that these stories are far from fixed. They emerge as part of the political effort to mobilise against the mining, transforming the contexts in which they emerge. This involves encounters of epistemological tension and multiple worlds, as “divergent knowledge come together in unexpected ways” (ibid: 407). What is significant is that local sacred spirits such as Apu were mobilised, translated through the language of Catholicism, and successfully “travelled” beyond a religious audience, enrolling a divergent array of political supporters who embraced the mountain’s “multiple forms in ways that helped to strengthen their claims” (ibid: 409).

Like Li, I want to acknowledge the presence of multiple worlds, filled with stories that exceed a secular and singularly oriented understanding, or what Law (Reference Law2015) has called a “one-world world”. This calls for a way of writing that “maintains divergences among perspectives proposed from worlds partially connected in communication” (de la Cadena, Reference De la Cadena2015, p. 27). But how can we include such stories of unexpected accidents, while avoiding a fixation that locates such stories in the realm of “superstition”, or relics of a pre-Christian past? How do we navigate such versions of the real, without causing further harm, or undermining the political credibility of those involved?

The cautious mention of a falling rock does not constitute a group of “believers”. Rather it can be seen as a subtle invitation (or warning) to approach the mountain with greater caution and care. Anthropologist Alice Street (Reference Street2010) has proposed a theory of belief as relational action. Belief, she argues is much more than statements about causal relations and explanations of misfortune, or disease. Rather, they reflect perceived “possibilities for intervening and transforming” the relationships in question, and the prospects of ‘efficacious action’ upon them” (ibid: 268).

Approached in this way, casual references to sieidi could be interpreted, not so much as a statement about causality, but rather as tentative speech acts that propose a reconfiguration of a set of relations between Elkem, the Chinese investors, the mountain, and its beings. These relations are then neither fixed, nor anchored in completely separate worlds, but dynamic and subject to the ongoing transformation in various knowledge encounters.

In this perspective, neither Giemaš, nor the quarry or sieidi, are stable material entities. Rather, they may be understood as partly overlapping sites of relational practices that together constitute – or interrupt – what is, and what may become in the future. In this layered multiplicity, the various stories being told (about reindeer, about sieidi, about jobs) are sets of relations that can be mobilised as interruptions, resistance, or convergence. However, pointing out a layered multiplicity is hardly going to change much. We need to pay attention to the political and epistemic context in which stories emerge.

Sámi relational encounters – past and present

The earliest inscriptions of such ideas by Sámi speakers took place in the aftermath of the so-called Kautokeino rebellion in 1852 when the local elite was attacked by a group of Sámi herders and their families, who killed the Norwegian governor and the Norwegian merchant (Oskal et al., Reference Oskal, Ijäs and Bjørklund2019). Two of the rebels were sentenced to death and beheaded. The rest of the participants were imprisoned, some with life-sentences. Two prisoners, Lars Hætta and Anders Bær, who were both illiterate and with limited knowledge of the Norwegian language were recruited by the priest and linguist Jens A. Friis. For him, the Sámi-speakers’ imprisonment in the capital offered a unique opportunity to produce a first handwritten account of Sámi life and customs prior to the political upheaval. In their accounts, references to non-Christian spirituality (and sieidi), are rather vague, denied, or set in the past. Their texts are testimonies to the brutal asymmetry involved in this early colonial knowledge encounter, as well as an early documentation of Sámi relational approaches to the local landscape (Oskal et al., Reference Oskal, Ijäs and Bjørklund2019).

Friis subsequently published the texts, and this highly asymmetrical collaborative research paved the way for subsequent knowledge encounters, and newly written testimonies, such as those published by the linguist, ethnographer, and cultural historian, Qvigstad (Reference Qvigstad1927). At the height of the era of cultural assimilation, and based on a racialised evolutionist understanding that sought to eradicate Sámi culture, Qvigstad collected numerous stories, some of which were published in a book called “Lappish fairy-tales and myths from Varanger” (Qvigstad, Reference Qvigstad1927). One story is entitled “how sacred sacrificial sites are harmed”. Several ways of harming stones are mentioned, but only fire can destroy them:

“With fire, even a large rock will be destroyed, because a stone that is a sacred stone is chosen above all stones. On it, there is a layer of reindeer fat, and the whole stone is covered by fat and is a beautiful thing and pleasing to look at, because it is shining and it shines.” (Qvigstad, Reference Qvigstad1927, pp. 464–465, translation from Norwegian by author).

Then the story explains how the stone was burned by a man named Olav. An unsuccessful hunting trip had made him doubt the powers of the sieidi. He grew angry, and to test its powers, he finally decided to burn the sieidi, and destroyed it.

“the great fire broke it into pieces and it was no longer appropriate for people to serve the stone or have it as God. Many, who had stood by the sacred stone, they mourned for a long time, and a lot, over … their perfect and self-made beautiful sieidi… It was their great love for it that made them mourn, when the sacred stone that was so well prepared, was burned.” (pp. 464–465 translation from Norwegian by author).

While these stories are all set in the past, they resonate with contemporary oral histories that seek to articulate a holistic approach to the natural surroundings, as part of the experience of living in the North. Introducing a sound installation, Kramvig and Petterson, for example, emphasise the gratitude and sensitivity to every living thing, as well as the recognition of powers of animals, stones, lake, rivers, and weather that has formed the peoples of the North, and that are conveyed by oral storytelling (Kramvig & Petterson, Reference Kramvig and Petterson2016).

Analysing Sámi concepts of relational practices between humans and environmental formations, Østmo and Law (Reference Østmo and Law2018) suggest that jávredikšun, which could be translated as lake care, “is in some measure predicated on indirect long-term return and forms of (possibly unequal) reciprocity between powerful and independently willed actors” involving moments of gift giving and blessing. They relate this to how the sieidi stone was offered oil, while the lake was being blessed, reflecting long-term relations and obligations:

“gift giving only makes sense in a world populated by actors endowed with the moral sensibility to recognize and respond to respectful and disrespectful behavior, which is how it is on the Arctic plateau, where lakes, like other powerful beings, may be offended” (Østmo & Law, Reference Østmo and Law2018, p. 361).

The authors argue that “for Sámi people, fishing is about respectful relations with fish and lakes” (ibid: 353). But the practices involved in fishing also involve offering stones, or sieidi: “People need to give, they cannot simply take, and least of all should they quarrel with a sieidi.” (ibid. 354). But how far can such stones and stories travel?

Tracing interruptions online

Late in the evening, I research the quartzite quarry on my computer. With Google as my research assistant, I learn that the first stages of planning that could lead to a re-regulation of the entire area for mining activities has just begun. The online report prepared by the consulting company Sweco for Elkem had been presented to the public in March 2016 (SWECO, 2016). Labelled detailed regulation for the quartzite quarry at Geresgohppi, Giemaš og Vággečearru, it contains 50 pages of detailed mapping and description, listing all the things that allegedly should be taken into account in the upcoming process. I learn that Elkem Tana is one of the largest producers of quartzite worldwide, with a total of approximately one million tonnes of quartzite shipped out through the narrow sound every year. The operations employ a total of 41 people (not all are local). I study the Sámi spelling of names of mountain ranges that are new to me, and learn that the expansion will involve a sixfold increase of the total quarry area from 2.5 km2 today, to 15 km2 if the plans are realised. The operations will require a dredging to make the sound deeper, in order to secure future marine transport. The sound marks the boundary of the Tana/Deatnu river mouth Nature Reserve, a delta- and wetland area that provides a resting and feeding area for numerous migrating birds, as well as a breeding area for seal, and one of Norway’s Ramsar-protected wetland sites designated to be of international importance through the UNESCO Ramsar convention, but also the near one of Norway’s most famous and protected salmon rivers, Tana river/Deatnu (see Ween, Reference Ween2020).

I had heard local people mention many of these relations, but it is through SWECOs report that I get the first comprehensive overview of the quartzite quarry complex, replete with detailed maps, bird’s eye photos, and descriptions that are more detailed than I could ever have assembled myself. It is all there online, conveyed to me a late summer evening, through images on my computer screen, and I realise that this is already a train-in-motion, instigated according to the temporalities of Norwegian state and municipal governance procedures. The planned expansion exists, online, with its own specific temporal trajectory, filled with milestones and hearings. Following the hearing in spring 2016, Sweco was once more hired by Elkem to produce a full impact assessment. Such is the mandate of the consulting company, and they pay consultants who dedicate the time it takes.

Part of the purpose of a hearing like this is to identify all the potential entities that may be affected, in connections with “requirements for an impact assessment”. These include reindeer herding, contamination, interventions in the landscape, biodiversity, local economy, recreation, transport infrastructure, and “Sámi culture and nature practices” not covered above. It is as if the anticipation of a future trial is already inscribed in the process from the beginning. “Does the quartzite quarry impact on the category ‘recreation value’ or not?” “Does it interfere with pastureland for sheep”? But domains of life in this region do not always coincide with the categories of a report. And I wonder what it is that my friends are doing when they spend an evening picking blueberries: is it recreational? Would they be required to identify as Sámi in order to be recognised?

And what about the sieidi? Not surprisingly, it is mentioned too, albeit discreetly, towards the end of the list under the heading “cultural heritage”. I learn that there are two sites of interest: one is a burial site from the bronze age, which is automatically protected according to Norwegian law. The other is a cultural heritage site of “limited public knowledge” [“kulturminne med begrenset offentlighet”] located just east of the quarry near Geresghoppi (SWECO, 2016, p.30). It is all visible online if you Google properties in Norway (www.seeiendom.no). The discreteness of the sieidi is thereby broken, but its mobility and legibility remain confined to a local context.

The following year, in spring 2017, I happened to meet Yngve again, my host in Lavvonjarg, In the meantime I had come across a text from 1767, by Knud Leem (Beskrivelsen over Finnmarkens Lapper), and I had identified seven place names that might indicate sacred mountains along the Deatnu river. Yngve had been involved in a project trying to name all the sacred sites on the Varanger Peninsula. Did Yngve know about these names? On email, he had confirmed that five of these were familiar and as we met in the cafeteria of the Sámi University College he drew a simple map on the back of a napkin, pointing out approximately where they were located.

I took the opportunity to share my draft version of this paper with him. Had I revealed too much? Was he willing to be named? He was, and told me about a sieidi called Guompegueldi (literally: wolf-forbid past), that used to be up at Giemaš, He also told me more about the accidents: Three or four incidents of fire outbreak. Two or three times when the pier had fallen out into the water. Originally the quartzite quarry was supposed to be started near his home. They had several trials there, and if they had placed the quarry there, it might have damaged the surroundings even more than at the current quarry site. “But that was the idea in those days”, he explained: “One had to sacrifice something for development”.

Care, caution, and indeterminacy

The planned expansion of the quartzite quarry is not a case of rampant multinational land grabbing from a local indigenous community, incapable of defending its interest in the state judicial system. The territory in question was handed back in 2005 from state to regional and indigenous ownership, through the so-called Finnmark Act which grants ownership of most of the territory in Finnmark to FEFO (the Finnmark property, for details, see Ween and Lien, Reference Ween, Lien, Head, Saltzman, Selten and Stenseke2017). In 2019, and with a narrow majority, FEFO voted against the expansion, but FEFO cannot veto the proposed plans, and in 2020, the county governor has warned against environmental impact on the marine environment. But none of this can guarantee that the process will come to a halt. Perhaps it will proceed as proposed. Perhaps it will end up in court, and exacerbating and amplifying existing rifts in the local village. What then, does it take to acknowledge the mountain for everything that it is? How may affective relations come to matter? Will there be a space for the pluriverse in political processes?

Kramvig (Reference Kramvig and Miller2015) has argued that in order to face global warming and take on the responsibility that we as humans have for the future of the planet, we could learn from Arctic ontologies where people live with the land, the animals, and other-than-human entities that exceed the realm of what is publicly known. Historically, the sieidi has had many roles, one of them was to signal the way. Like cairns, they pointed wayfarers in the right direction. But they were also, as Kramvig and Verran (Reference Kramvig, Verran, Henriksen, Hydle and Kramvig2020) point out, an institution of moral governance, regulating human behaviour through protocols of fairness, politeness, honesty, and respect. Perhaps the interruptions of sieidi that unfold in Finnmark today are particularly timely. If we see with these sieidi as cairns to navigate an uncertain future – a future replete with unexpected twists and turns of governance processes and environmental impact – then perhaps, we might create a broader base from which to find a way. Situated between a troubled past and an unknown future, the sieidi stories are broken, their presence is hardly known, yet their unexpected interruptions instigate calls for care and caution in uncertain worlds.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to friends and acquaintances in the Varanger region for generosity and friendship, and for sharing their concerns regarding the planned quartzite quarry. I also wish to acknowledge the importance of conversations at Sámi Állaskuvla (Sami University College), and especially Liv Østmo and Solveig Joks, for valuable advice on how to navigate Sámi concerns and challenges. Earlier versions of this manuscript were presented at the Berkeley REDO Workshop, “Environmental change and ritualized relationships with the other-than-human world” in October 2016, and at the REXSAC workshop Uchronotopia, Lysebu in November 2017. I am grateful to participants at both of these events for their valuable comments, as well as to Kirsten Thisted and Frank Sejersen, Editors of Special Issue of Arctic Uchronotopias. Matt Tomlinson at the University of Oslo alerted me to relevant debates concerning the concept of “belief” and helped me clarify my argument as a result. Britt Kramvig, John Law and Gro B. Ween have inspired and guided me for many years, and I am grateful to the ongoing conversations.