Introduction

As restrictions on the wearing of religious symbols emerge in parts of Europe and North America, religious diversity has become as a significant source of conflict in Western societies. Understanding what motivates support for the rights of different group members to wear religious symbols is a pressing social issue. When deciding which religious groups are deserving of accommodation, there is typically less willingness to support religious minorities, especially Muslims (e.g., Wright et al. Reference Wright, Johnston, Citrin and Soroka2017; Hirsch et al. Reference Hirsch, Verkuyten and Yogeeswaran2019). Further evidence points to a double standard among certain individuals in Western countries who support bans on Muslim but not Christian religious symbols (Bilodeau et al. Reference Bilodeau, Turgeon, White and Henderson2018; Dangubić et al. Reference Dangubić, Verkuyten and Stark2020).

What accounts for this weaker support offered to religious minorities? At the individual level, much of the research on public attitudes and opinions toward religious symbols highlights the importance of social and political values (e.g., Van der Noll et al. Reference Van der Noll, Saroglou, Latour and Dolezal2018; Turgeon et al. Reference Turgeon, Bilodeau, White and Henderson2019; Dangubić et al. Reference Dangubić, Verkuyten and Stark2020) or prejudice (e.g., Helbling Reference Helbling2014; Van der Noll and Saroglou Reference Van der Noll and Saroglou2014; Bilodeau et al. Reference Bilodeau, Turgeon, White and Henderson2018). Missing from this research, however, is an understanding of how groups' membership in, and relationship to, the national community affect public acceptance of the right to wear religious symbols. Such beliefs about national membership are found to be relevant for attitudes toward immigrants and ethnic minorities (Pehrson and Green Reference Pehrson and Green2010; Smeekes et al. Reference Smeekes, Verkuyten and Poppe2011) along with policy preferences toward increasing access to redistribution and social spending (Harell et al. Reference Harell, Banting, Kymlicka and Wallace2021). Do perceptions of religious group members' membership and inclusion into the national community also play a role in shaping more symbolic policy preferences toward religious symbols in public life?

Compared to Christian symbols, public opinion surveys typically show significantly less support for religious minority symbols (Wright et al. Reference Wright, Johnston, Citrin and Soroka2017; Angus Reid 2018). One factor which may contribute to explaining the weaker willingness to support the rights of Muslims and other religious minorities to wear religious symbols in public may stem from the different beliefs individuals hold about the inclusion of these group members into the national community. When deciding which groups should be afforded the right to wear religious symbols in public, beliefs about membership in the national community may sway our thinking. In this sense, more familiar and traditional religious group like Christians may be construed as particularly committed members, or at least members with privileged status due to their longstanding presence in the country, whereas Muslims and other religious minorities, as relative newcomers to Western societies, may be perceived as outsiders. This distinction may in turn activate different stereotypes about the commitment of different religious group members to the nation, weakening support for the rights of religious minorities to wear religious symbols in public.

Data to test this expectation are drawn from a national survey experiment (N = 974) fielded in 2020 with Canadian citizens and permanent residents. In understanding public opinion toward religious symbols, the Canadian case is highly relevant. The country is a diverse, multicultural society that has undergone vigorous debate over the presence of religious symbols in public settings. While legislation banning the wearing of religious symbols by public servants in positions of authority, including public school teachers, has been implemented in the province of Quebec since June 2019, neither the Canadian federal government, nor any other provincial legislature has taken such action. Although attempts have been made in other provinces to restrict the wearing of religious symbols in some school settings, within the federal police force, and while taking an oath to citizenship, these efforts have been rejected by the Supreme Court of Canada. Nonetheless, Canadian public opinion remains divided over whether or not to accept the wearing of religious symbols by public servants in positions of authority (Angus Reid 2018; Léger 2019) and bans on religious symbols, and their subsequent court challenges, have a long history in other provinces beside Quebec and at the federal level as well (Wayland Reference Wayland1997; Bridgman et al. Reference Bridgman, Ciobanu, Erlich, Bohonos and Ross2021). The Canadian case therefore provides an important opportunity to test how social perceptions influence attitudes toward religious symbols in a context where the debate over religious symbols is highly salient.

Public Reactions Toward Minority Religious Symbols and Heritage Practices

Research on attitudes and opinions toward religious diversity has highlighted the importance of different factors in shaping responses to religious accommodations and the public display of religious symbols. Differences in ideological beliefs and values are often used to explain policy preferences toward religious accommodations, including support for bans on religious symbols (Van der Noll Reference Van der Noll2014; O'Neill et al. Reference O'Neill, Gidengil, Côté and Young2015; Ferland Reference Ferland2018; Turgeon et al. Reference Turgeon, Bilodeau, White and Henderson2019). Much attention has been paid to the importance of social or political values and civil liberties (Saroglou et al. Reference Saroglou, B, M and C2009; Turgeon et al. Reference Turgeon, Bilodeau, White and Henderson2019; Dangubić et al. Reference Dangubić, Verkuyten and Stark2020; Van der Noll Reference Van der Noll2014) and group-specific prejudice (Helbling Reference Helbling2014; Van der Noll and Saroglou Reference Van der Noll and Saroglou2014; Bilodeau et al. Reference Bilodeau, Turgeon, White and Henderson2018), sometimes placing these considerations in conversation with one another (Helbling Reference Helbling2014; Bilodeau et al. Reference Bilodeau, Turgeon, White and Henderson2018; Dangubić et al. Reference Dangubić, Verkuyten and Stark2020). Researchers have also made the important distinction between those who favor restricting all religious symbols from those who support restrictions only on religious minority symbols, while preserving the privileged position of Christian symbols in public settings (Bilodeau et al. Reference Bilodeau, Turgeon, White and Henderson2018; Dangubić et al. Reference Dangubić, Verkuyten and Stark2020). Absent from the public opinion research, however, is an understanding of how national membership is construed and how perceptions of other's commitment to the national community shape reactions to religious symbols.

Considerations over religious symbols and the role religious minorities play in the national community have captured a great deal of media attention in recent years. Much of this coverage has focused on the lack of fit between religious minority practices and societal values of gender equality and secularism (Scott Reference Scott2007; Giasson et al. Reference Giasson, Brin and Sauvageau2010). Such framing makes markers of religious identification particularly salient. As a result, considerations about minority religious practices may have important implications for social and political attitudes. For example, whereas assimilation and the shedding of foreign cultural practices have been associated with a reduction in negative beliefs about minorities (Roblain et al. Reference Roblain, Azzi and Licata2016), the maintenance of heritage practices may be met with opposition from majority group members who construe such behavior as signaling a weaker commitment to the larger society (Bourhis et al. Reference Bourhis, Moise, Perreault and Senecal1997; Van Oudenhoven et al. Reference Van Oudenhoven, Prins and Buunk1998; Verkuyten et al. Reference Verkuyten, Thijs and Sierksma2014). Religious symbols may therefore pose a challenge to the inclusion of religious minorities as full members of a shared national community.

These stereotypes about how religious groups relate to the nation may in turn have important repercussions for policy attitudes and support for minority rights. In Canada, as in the United States and the United Kingdom, stereotypes about individuals of Middle Eastern background are associated with increased opposition to immigration, while Arab, Muslim, and Middle Eastern migrants are often characterized as outsiders and ascribed negative attributes. For example, these groups tend to be stereotyped as less warm and only moderately competent (Lee and Fiske Reference Lee and Fiske2006), are perceived to be a source of symbolic threat (Hitlan et al. Reference Hitlan, Carrillo, Zárate and Aikman2007) or to be violent and untrustworthy, perceptions linked to Americans' support for the “War on Terror” (Sides and Gross Reference Sides and Gross2013). In the Canadian case, stereotypes of Middle Eastern immigrants are more influential in shaping immigration policy preferences than stereotypes of other immigrant groups, such as South Asians (Konitzer et al. Reference Konitzer, Iyengar, Valentino, Soroka and Duch2019), although such cultural markers are not always the most important cues shaping policy attitudes (Harell et al. Reference Harell, Soroka, Iyengar and Valentino2012).

National Membership and Support for Minorities

While socio-political values, perceptions, and beliefs about the maintenance of heritage cultural practices have been used to explain the disparate treatment of minority groups, an understanding of “who belongs” to the national community and how such considerations shape attitudes toward religious symbols more generally have received insufficient attention. Beliefs about who is included in the national community are important for discerning who should be able to avail of social policy supports. For example, considerations about policy beneficiaries' perceived reciprocity toward, and identification with, the larger society are important determinants of perceptions of deservingness and beliefs about who should be allowed to draw on policy benefits (van Oorschot Reference Van Oorschot2000, Reference Van Oorschot2006).

Recent research by Allison Harell and colleagues (Banting et al. Reference Banting, Kymlicka, Harell, Wallace, Gustavsson and Miller2019; Harell et al. Reference Harell, Banting, Kymlicka and Wallace2021) has brought greater conceptual clarity to the basis upon which judgments about the deservingness of different minority groups are made and how social perceptions of shared group membership influence the willingness to extend supports to minority communities. Beyond considerations of individuals' neediness and control over their situation, an understanding of “who belongs” in the national community influences inclusive redistributive attitudes toward minorities (Harell et al. Reference Harell, Banting, Kymlicka and Wallace2021). Might the categorization of religious group members as committed contributors to the nation also play a role in shaping more symbolic policy attitudes such as support for the rights of religious minorities to wear religious symbols in public?

Opposition to the rights of Muslims in Western societies, including the right to freedom of religion, may be symptomatic of a broader tendency to oppose extending benefits to groups that are perceived as outsiders who are less deserving of assistance. Extensive research on welfare chauvinism finds that, compared to other groups including seniors, the poor, and the unemployed, ethno-cultural minorities face strong opposition when it comes to drawing on social benefits (e.g., Harell et al. Reference Harell, Soroka and Ladner2014; Koning Reference Koning2019; Reeskens and van der Meer Reference Reeskens and van der Meer2019). Considering others to be co-nationals is associated with a greater willingness to extend social supports to others. But how generalizable are beliefs about the relative fit between minority groups and the national community to more symbolic policy issues like supporting the rights of different religious communities to wear religious symbols? As appeals to secularism and other “majority values” become used to justify restrictions on religious symbols in certain situations (Scott Reference Scott2007; Turgeon et al. Reference Turgeon, Bilodeau, White and Henderson2019), public opinion research continues to find a sizeable proportion of survey respondents who appear to take a stricter stance on the symbols and practices of religious minority groups (Wright et al. Reference Wright, Johnston, Citrin and Soroka2017; Bilodeau et al. Reference Bilodeau, Turgeon, White and Henderson2018; Dangubić et al. Reference Dangubić, Verkuyten and Stark2020). The potential for restrictions on religious symbols to be applied selectively depending on group membership violates core tenants of secularism, namely the principles of treating religious groups equally and legislating in a neutral manner, without favoritism or disproportionate restrictions on the rights of some religious groups.

Research on religious accommodation and attitudes toward restricting religious symbols has focused to a large extent on individual values and outgroup animosity. The public opinion literature has not examined the extent to which social perceptions of others' national commitment and membership impact support for the rights of different group members to wear religious symbols. Answers to questions about “who belongs” to the national community and how such perceptions affect support for the right to wear religious symbols remain to be seen. Minority religious symbols are especially prominent markers of identity that may make considerations about group membership and national commitment all the more salient. These social perceptions offer an untested explanation for the “accommodation gap” that results in stronger support for the rights of more traditional religious communities to wear religious symbols. Given the importance of an ethic of shared national membership for other forms of social solidarity (Harell et al. Reference Harell, Banting, Kymlicka and Wallace2021), the extent to which various religious groups are perceived as sharing—or not—in a commitment to the larger national community is theorized to affect public attitudes toward the right to wear religious symbols in different settings. The present research is designed with these questions in mind.

Hypotheses

Two central questions are examined in this study relating to how religious group members' perceived commitment to the nation influence supports for the right to wear religious symbols. First, the research asks what beliefs individuals hold about the commitment of Christians and minority religious groups, particularly Muslims, to the national community. Second, what effect, if any, do these judgments have in shaping support for the rights of others to wear religious symbols?

Data are drawn from a large survey experiment in Canada. Given the privileged status of Christians as a well-established religious group in the country,Footnote 1 the increased cultural distance religious minority symbols may elicit could result in religious minorities being perceived as relative outsiders to the national community compared to Christians who may benefit from the perception that they, as a group, are committed Canadians (Hypothesis 1). These judgments about religious group members' commitment to the national community are expected to be an important consideration that shapes support for the right to wear religious symbols (Hypothesis 2). More specifically, national membership considerations are hypothesized to be especially important for shaping attitudes toward wearing minority religious symbols in public. When individuals perceive religious minorities as equally, if not more, committed contributors that identify with the national community, the disparity in support shown for the rights of religious minorities to wear religious symbols is expected to significantly weaken, if not disappear entirely (Hypothesis 3).

Data and Methods

Data were collected from a survey module within the 2020 Democracy Checkup (Harell et al. Reference Harell, Stephenson, Rubenson and Loewen2020), an online survey conducted between May 5 and 12, 2020.Footnote 2 A sample of Canadian citizens and permanent residents over the age of 18 was recruited by the survey firm Dynata, with quotas for age, gender, province, and, within Quebec, language, as per the 2016 Canadian census. Inattentive respondents were removed from the dataset if they completed the survey in under one-third of the median completion time; demonstrated straight-line responding on matrix tables throughout the survey; as well as those whose postal codes and reported province of residence did not match.

The final sample for the present research consisted of respondents completing a survey module on religious accommodation (N = 974). Of these respondents, 515 (52.9%) were women, with an average age of 49 years (s.d. = 17.07). About half of respondents (n = 505; 51.8%) reported some university education and approximately 21% (n = 203) of respondents reside in Quebec. With respect to their religious background, 30% (n = 289) identified as atheists, 48% were Christians (n = 468), and 2.5% (n = 24) self-reported being of Muslim faith. As a result, the sample is comparable to Canadian population with respect to gender and university education but is somewhat older than the Canadian population. The small sub-samples of respondents preclude generalizations based on religious background or province of residence. Survey responses are weighted based on the 2016 Canadian census, according to province, gender, age group, and, within the province of Quebec, language (i.e., English and French). Missing data for multivariate analyses are handled via multiple imputation. At the start of the survey module, respondents were randomly assigned to one of three experimental conditions, which asked participants to make judgments about their perceptions of the commitment of either Christians, Muslims, or “religious minorities” in general, to the Canadian national community. Afterward, respondents were asked questions about whether members of their assigned religious group should be allowed to wear religious symbols in different situations.

Measures

Beliefs about National Commitment

Four items adapted from previous research on Canadians' beliefs about the commitment of different groups to a shared national community (Harell et al. Reference Harell, Banting, Kymlicka and Wallace2021) are used as the primary independent variable of interest. These items assessed judgments about religious group members' (i.e., either Christians, Muslims, or “religious minorities,” randomly assigned) level of perceived national identification with Canada along with three additional measures of how thankful group members are for the supports they receive; how much group members are perceived to care about the concerns and needs of other Canadians; and group members' perceived willingness to make sacrifices in support of other Canadians. Items are measured in a relational way, such that scores reflect whether different religious groups are more or less likely to be seen as committed to the national community relative to other Canadians. Items were evaluated from 1 (much less than other Canadians) to 5 (much more than other Canadians), with the midpoint signaling “about the same” as other Canadians. See Appendix A for question wording and Appendix B for latent variable analyses. Confirmatory factor analyses (reported below) show these items load highly on a single common factor with strong internal consistency (α = 0.86).

Acceptance of the Right to Wear Religious Symbols in Public

Respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree that members of the randomly assigned religious group should have the right to wear their religious symbols (i) when studying at public schools or universities; (ii) in public, while walking in the street; and (iii) when working for the government as public school teachers, judges, or police officers. Each item was measured on a seven-point agree–disagree scale, recoded to range from 0 to 1 with higher scores reflecting more support for the right to wear religious symbols. Items were also summed and averaged into an index of support for the right to wear religious symbols across situations, with strong internal consistency for Christians (α = 0.91), Muslims (α = 0.94), and religious minorities (α = 0.94).

Control Variables

Several demographic and psychosocial variables are included as co-variates in the multivariate analyses to control for individual differences that may influence willingness to support minority groups. Demographic controls include age, respondents' gender (female = 1), their province of residence (scored 1 if a respondent is from Quebec, otherwise 0), as well as dummy variables for education (scored 1 if a respondent has a university-level education, otherwise 0) and religious affiliation captured with three dummy variables each contrasting Christians, Muslims, and Atheists to all other religious groups. Psychosocial correlates of intergroup and policy attitude are also controlled for, including social dominance orientation (SDO) and empathy, along with respondents' own Canadian identification. To control for individual differences in SDO, an important antecedent of prejudice (Sibley and Duckitt Reference Sibley and Duckitt2008) and a key predictor of attitudes toward intergroup inequality (Pratto et al. Reference Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth and Malle1994; Ho et al. Reference Ho, Sidanius, Pratto, Levin, Thomsen, Kteily and Sheehy-Skeffington2012), two items tapping egalitarian and anti-egalitarian dimensions of the construct are used. Respondents rated their agreement with each item on a four-point scale recoded from 0 to 1 such that higher scores reflect stronger preference for group-based inequality (r = 0.16, p < 0.001). To control for general pro-social behaviors associated with social justice and concern for the treatment of minorities (Segal Reference Segal2011; Sirin et al. Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2017), empathy is measured with two items asking respondents how often they engage in perspective taking (r = 0.77, p < 0.001). Finally, in light of the relational nature of the shared membership items, which measure groups' perceived commitment and contribution to Canada relative to other Canadians, two further items are included which control for respondents' own Canadian identification (r = 0.47, p < 0.001).

Results

Religious Group Members’ Perceived Commitment to the National Community

Before examining whether support for the rights of different group members to wear religious symbols in public is determined by their inclusion in the national community, we first examine the dimensionality of the membership measure along with the basis upon which judgments about different religious groups' relationship to the nation are construed. In line with previous work on the perceived national commitment of other ethnocultural and linguistic minority groups (Harell et al. Reference Harell, Banting, Kymlicka and Wallace2021), the membership scale is found to form a coherent, unidimensional factor when respondents are asked to make judgments about group members from traditional (i.e., Christian) and minority (i.e., Muslim or “religious minority”) religious communities. A multigroup confirmatory factor analysis specifying a single latent variable with missing data handled via full information maximum likelihood estimation shows a one-factor model to be an excellent fit to the data for all randomly assigned religious groups (CFI = 0.997, TLI = 0.992, RMSEA = 0.049). Table B1 in the supplementary materials reports the factor loadings for each membership criterion by assigned religious group.

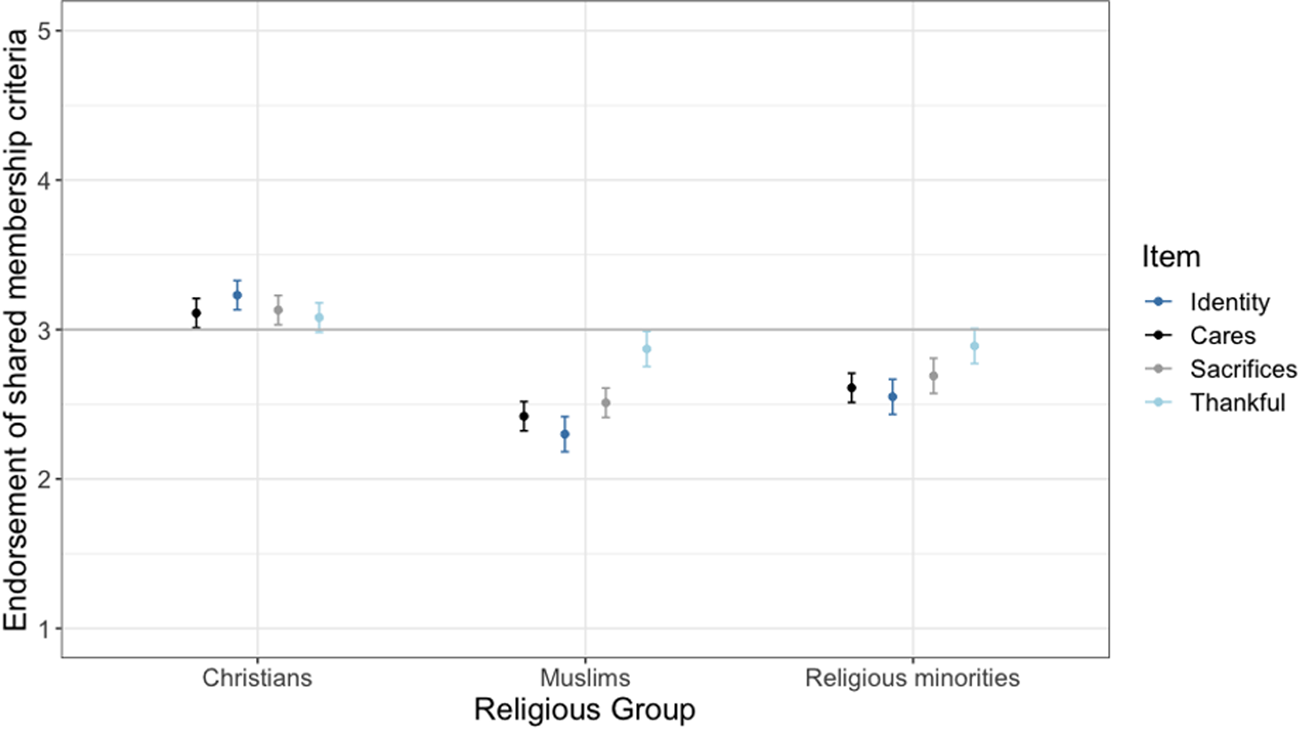

Which criteria do individuals most rely on to make inferences about the commitment of these different religious groups to the national community? To further test how considerations about the relationship between religious groups and the nation vary, item response theory is applied to estimate a two-parameter logistic graded response model.Footnote 3 Detailed results of the latent variable modelling of respondents' perceptions of religious group members' national commitment are presented in Appendix B. Taken together, the results of these latent variable models show that judgments about the relative national commitment of religious minorities are not driven solely by a weaker perceived national identification; considerations about how appreciative and caring different religious groups are, along with their willingness to make sacrifices on behalf of others, also figure into respondents' perceptions of group members' commitment to the nation. Figure 1 plots respondents' average endorsement of each item for the three target religious groups. The data clearly show how different judgments are used to discern how Christians and religious minorities are thought to relate to the national community. The impressions respondents hold toward these religious groups benefit Christians, who are viewed as particularly committed Canadians, especially in terms of their perceived national identification, but disadvantage religious minorities, especially Muslims, who are stereotyped as significantly less committed and identified to the nation.

Figure 1. Average endorsement of shared membership items by religious groups. Higher scores reflect more of the attribute compared to “other Canadians.” The horizontal line at y = 3 indicates the mid-point of the scale, “about the same as other Canadians” (95% confidence intervals)

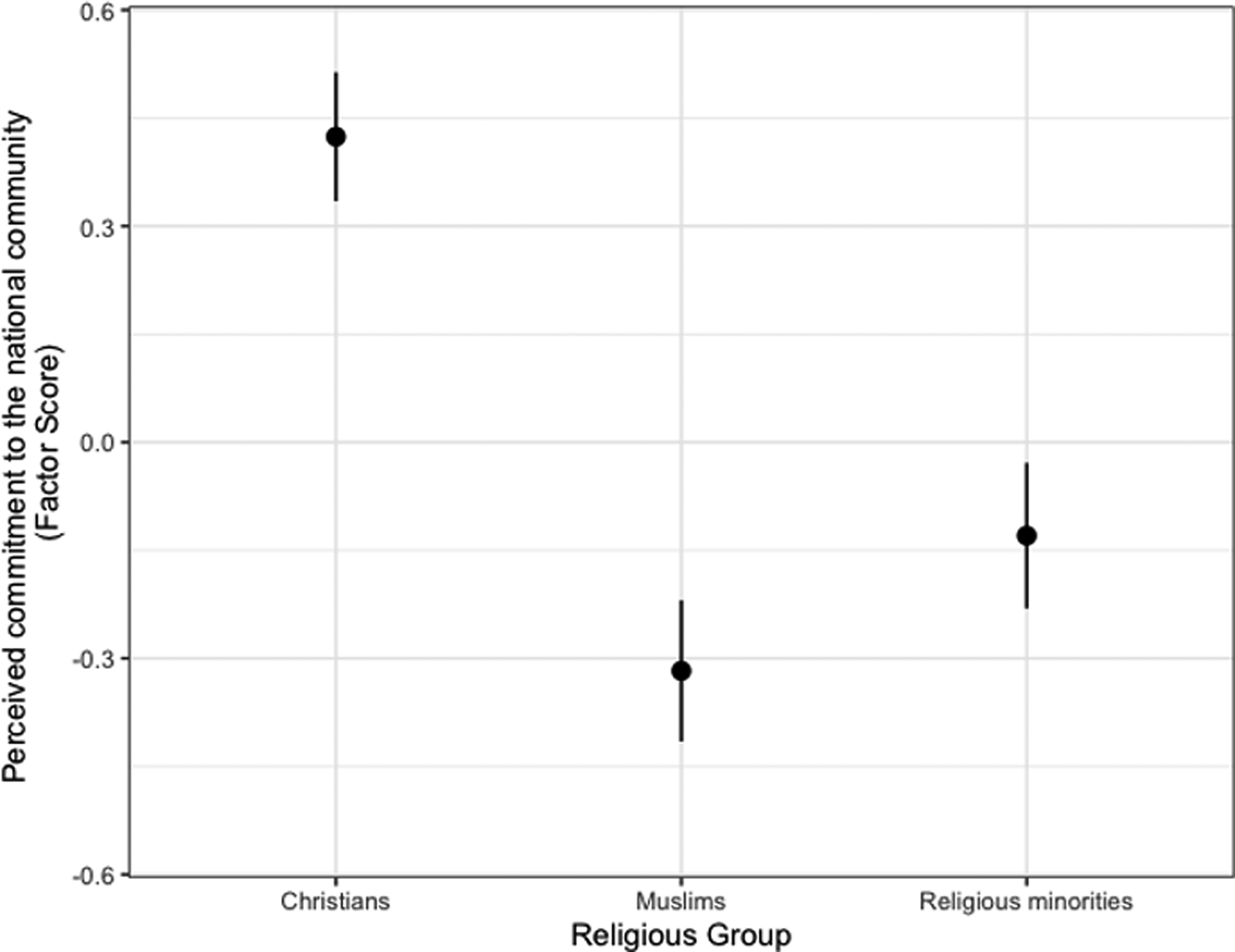

To integrate the weighting of these different considerations into an overall measure of religious group members' perceived commitment to the nation, factor scores are extracted based on the latent variable models presented in Appendix B. Group means for these latent measures of national commitment for each randomly assigned religious group are plotted in Figure 2. In line with Hypothesis 1, beliefs about how these religious groups are thought to relate to the Canadian national community clearly reflect a “hierarchy of membership” whereby religious minorities are judged as less committed to the national community. Both Muslims and religious minorities suffer a membership penalty, however Muslims appear to be particularly excluded and are stereotyped as less committed and identified to the nation compared with respondents presented with the generic “religious minorities” label.

Figure 2. Factor scores measuring latent beliefs about religious groups' commitment to the Canadian national community (95% confidence intervals)

Standardized scores on the latent mean-centered scale show Canadians' judgments of Christians' national commitment are particularly positive (mean = 0.42, s.d. = 0.85), indicating Christians are judged as even more committed members of the national community than the average Canadian. Evaluations are significantly more negative when judging Muslims (mean = −0.32, s.d. = 0.90) or “religious minorities” more generally (mean = −0.13, s.d. = 0.90). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the target religious group as a between-subjects factor shows these differences are statistically significant, F(2, 891) = 58.49, p < 0.001. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni-adjusted p-values find that compared to the Christian group, both Muslims (mean difference = −0.71, 95% CI [−0.91 to −0.57]) and religious minorities (mean difference = −0.55, 95% CI [−0.72 to −0.38]) are rated as less committed than the average Canadian. Muslims are especially viewed as outsiders; compared to Muslims, “religious minorities” are perceived as sharing more in a common group membership with other Canadians (mean difference = 0.19, 95% CI [0.02–0.36], p = 0.03). Although membership criteria that form the basis of Canadians' evaluations of Muslims and religious minorities are similar (see Figure 1), cueing “religious minorities” invokes slightly less distancing from the “typical Canadian” compared to cueing Muslims, particularly on the dimensions of perceived care and national identification.

Support for the Right to Wear Religious Symbols

Having examined the initial research question pertaining to respondents' judgments about how different religious groups relate to the Canadian national community, we now turn our attention to examining how these judgments influence support for the rights of different group members to wear religious symbols.

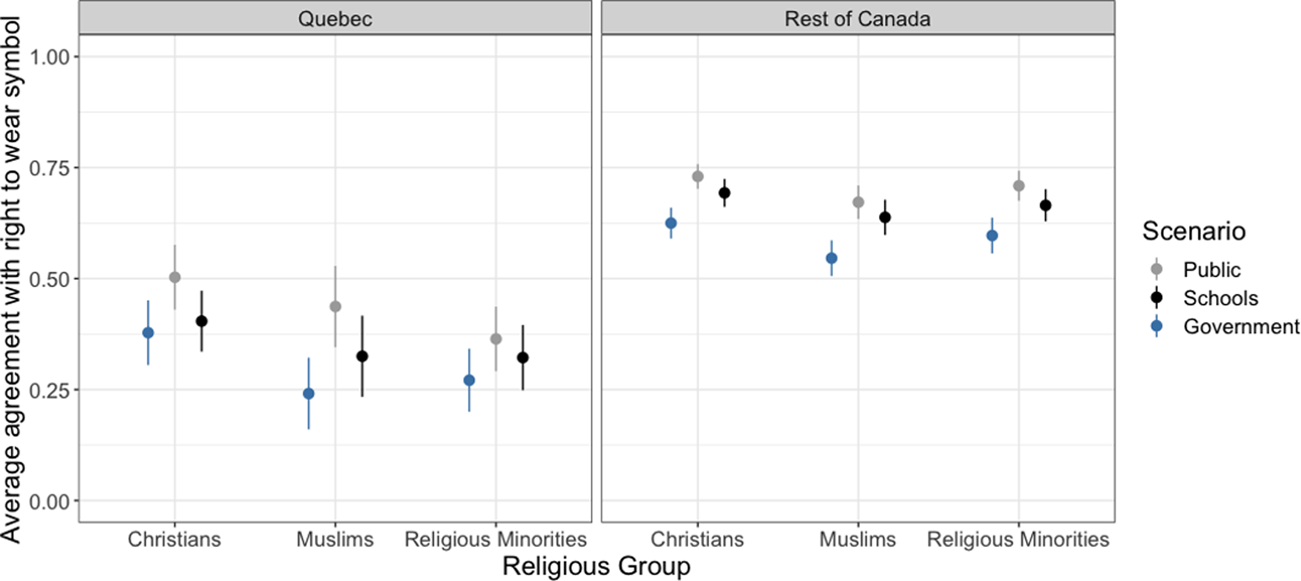

How supportive are respondents of the rights of different groups to wear religious symbols? Looking first at the summary statistics, the data indicate respondents are generally accepting of religious symbols in public (mean = 0.59, s.d. = 0.30). Support, however, varies as a function of the setting and group in question. Figure 3 visualizes the relationship between levels of support for each symbol across three settings, (i) while walking in the street in public; (ii) when studying in public schools or universities; and (iii) when working for the government as public school teachers, judges, or police officers. For comparative purposes, data are also presented separately for respondents residing in Quebec versus the rest of Canada because of the important sub-national differences within the country in how religious symbols are perceived (Bilodeau et al. Reference Bilodeau, Turgeon, White and Henderson2018; Turgeon et al. Reference Turgeon, Bilodeau, White and Henderson2019). Caution, however, is warranted as these comparisons are purely exploratory and should not be generalized to the wider population due to small sub-samples at the provincial level.

Figure 3. Acceptance of religious symbols under different circumstances, in Quebec and the rest of the country (95% confidence interval)

As Figure 3 clearly shows, respondents in Quebec (mean = 0.36, s.d. = 0.30) have significantly lower levels of support for the right to wear religious symbols compared to residents in other parts of Canada (mean = 0.65, s.d. = 0.27). To test these differences further, a 2 × 3 ANOVA is conducted with region (Quebec or the rest of Canada) and religious group (Christians, Muslims, or “religious minorities”) entered as between-subject factors. The results reveal a significant main effect for residing in Quebec, F(1, 917) = 174.69, p < 0.001, as well as a significant main effect for the religious group being evaluated, F(2, 917) = 4.94, p = 0.007. No significant interaction between residing in Quebec and the assigned religious group was detected, F(2, 917) = 1.29, p = 0.28, indicating that while overall support for the right to wear religious symbols differs among respondents in Quebec compared to other Canadians, the pattern of acceptance across situations is fairly consistent. Multivariate analyses will therefore proceed by pooling respondents from Quebec and the rest of Canada while controlling for whether respondents reside in Quebec.

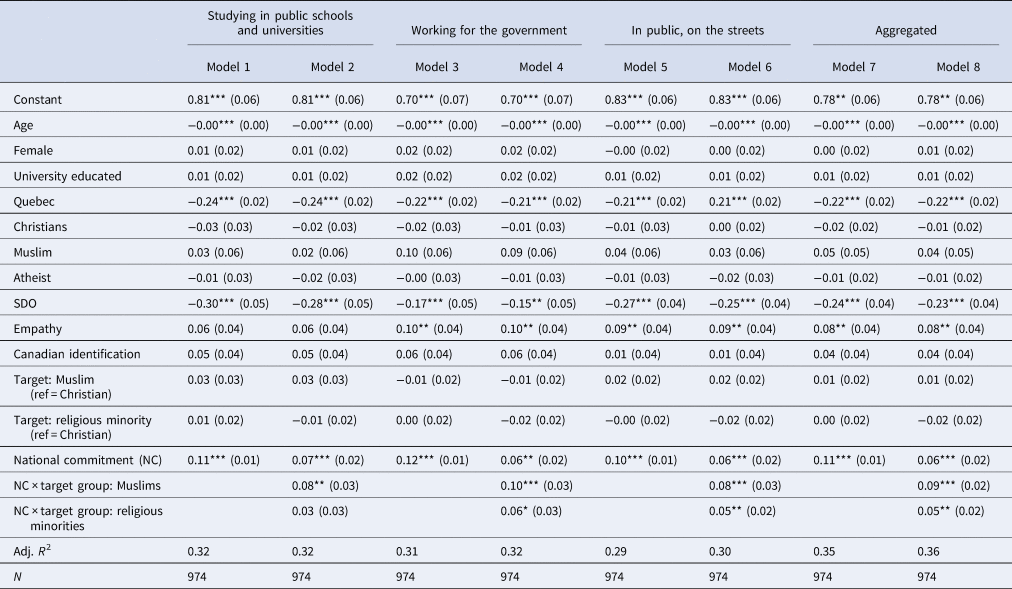

Recall that the primary expectation is that support for the right to wear religious symbols should increase in line with the perception that each group is committed to the national community. Moreover, such considerations are hypothesized to be especially important for determining support for the rights of religious minorities because the rejection of cultural assimilation and the maintenance of minority heritage practices are tied to negative evaluations by members of the host society (Bourhis et al. Reference Bourhis, Moise, Perreault and Senecal1997; Roblain et al. Reference Roblain, Azzi and Licata2016). The data support both these expectations. Results are presented in Table 1, which presents multiple linear regression models predicting situation-specific acceptance for wearing religious symbols (Models 1 through 6) and the aggregated measure of acceptance across all situations (Models 6 and 7).

Table 1. Linear regression results predicting support for right to wear religious symbols across situations

Standard errors in parentheses.

Note: Missing data are handled via multiple imputation pooling across 15 imputed datasets. Similar results are obtained when observations are excluded through listwise deletion.

***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

These multivariate results reveal distinct social cleavages in support for the right to wear religious symbols as well as the role of individual differences in shaping support for this religious freedom. The results show that controlling for other factors, older adults are consistently less supportive of the right to wear religious symbols, whether when studying in public schools or universities, working as government employees, or when walking in public on the streets. Moreover, the sub-national differences observed between Quebecers and other Canadians (see Figure 3) also persist, even after controlling for respondents' demographic and psychosocial characteristics, underscoring the cultural cleavage that persists around the issue in Canada. The analyses also show how psychosocial factors associated with minority rights extend to support for the right to wear religious symbols. Individuals scoring lower in SDO, along with those higher in self-reported empathy, are generally more likely to support wearing religious symbols. Canadian identification, on the other hand, is not a significant predictor of support for the right to wear religious symbols, independent of the other factors included in the model.

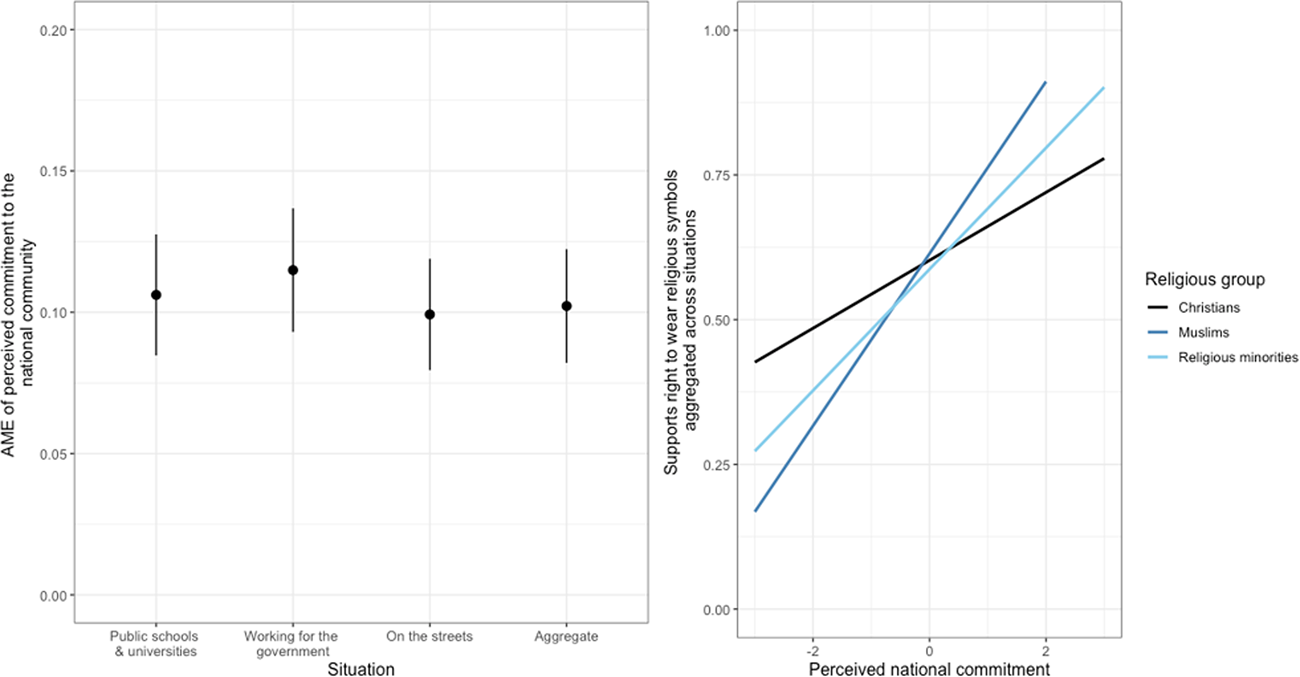

The data support the hypothesis that considerations about the national commitment of various religious groups is an important predictor of support for their right to wear religious symbols and, importantly, the influence of these considerations are especially relevant when judging religious minorities. Of particular importance for the present research is the interaction between the experimentally assigned religious group and respondents' perceptions of their commitment to the nation in predicting support for the right to wear religious symbols. These results are captured by the interaction terms in Table 1 and visualized in Figure 4 (right panel), highlighting how the impact of perceived commitment to the national community is stronger for religious minority groups than it is for Christians.

Figure 4. Average marginal effects, estimated from Models 1, 3, 5, and 7 in Table 1, of the effect of perceived national commitment on situation-specific support for the right to wear religious symbols (left panel) and the predicted level of support for the right to wear religious symbols by experimentally assigned religious group and respondents' judgments of religious group's perceived commitment to the national community (right panel). 95% confidence intervals shown

An analysis of the simple slopes of national membership considerations for the various experimentally assigned religious groups (see Figure 4, right panel) shows that the effect of perceived national commitment is stronger for Muslims (b = 0.15, s.e. = 0.02, 95% CI [0.12–0.18]) and religious minorities (b = 0.11, s.e. = 0.02, 95% CI [0.08–0.14]) than it is for Christians (b = 0.06, s.e. = 0.02, 95% CI [0.03–0.10]). Pairwise comparisons reveal that the only statistically significant difference in these trends occurs between judgments of Christians and Muslims (t(958) = −3.69, p < 0.001); no significant differences are detected when comparing Christians and other religious minorities (t(958) = −2.01, p = 0.11) or Muslims and the generic “religious minorities” label (t(958) = 1.76, p = 0.19).

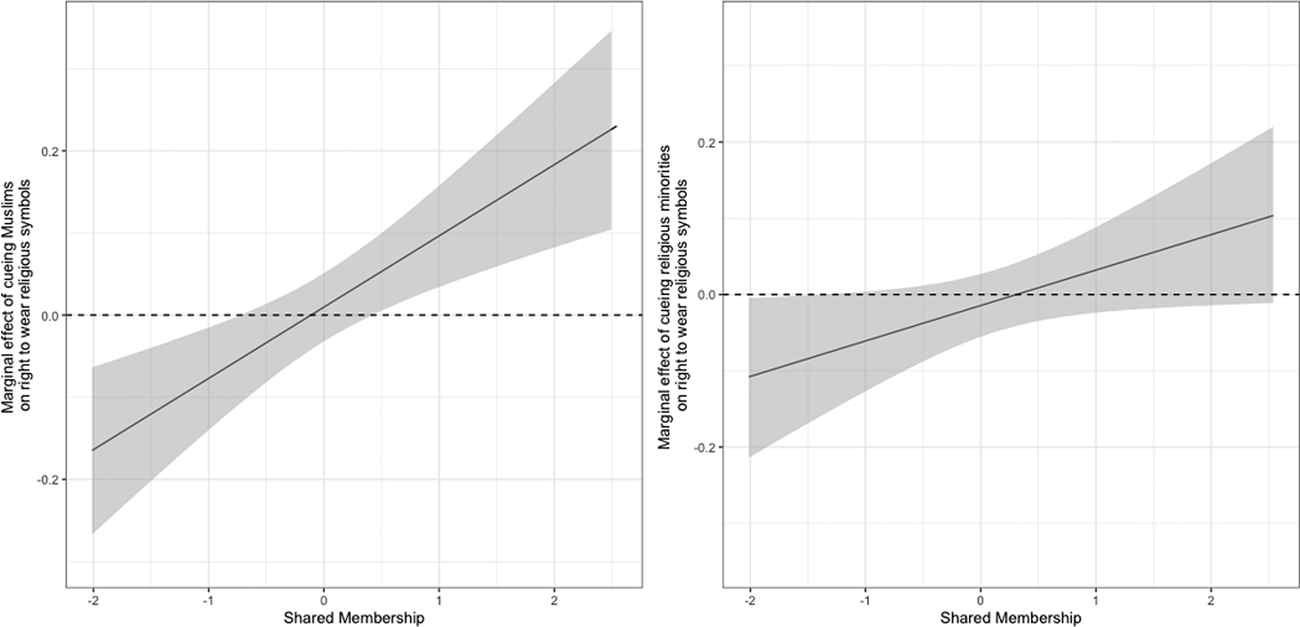

Importantly, the results show respondents' perception of the group members' commitment to the national community may close and, in the case of Muslims, even reverse the gap observed in individuals' tendency to be more accepting of Christian than religious minority symbols across a variety of situations. This conditional effect is visualized in Figure 5, which presents the change in the coefficient for cueing Muslims (left panel) or “religious minorities” (right panel) compared to cueing Christians at different levels of perceived national membership. When perceptions of either Muslims' or other religious minorities' national commitments are low, respondents are less accepting of their right to wear religious symbols. Religious minorities, however, are only penalized more than Christians when respondents hold especially exclusionary views on their shared membership in the Canadian national community. Interestingly, when tasked with making judgments about Muslims, the disparity in acceptance for Muslim versus Christian symbols not only disappears, but it also changes direction as membership perceptions of Muslims becomes more inclusive. Respondents who perceive Muslims as “about as equally” committed to the national community as other Canadians show no difference in their accepting attitudes toward wearing Muslim or Christian symbols in various settings. However, perceiving Muslims as especially committed members of the Canadian national community results in even higher levels of acceptance toward Muslim symbols across situations. While the survey experiment does not allow for a thorough examination into the causes of this change in attitude, the data provide a clear indication that support for the rights of different religious minorities to wear religious symbols is influenced to a significant degree by perceptions of religious group members' identification and overall commitment to the nation. In the case of Muslims, this perception may lead to substantially more acceptance for their right to wear religious symbols in different public settings.

Figure 5. Marginal effect of cueing Muslims or religious minorities versus Christians on support for the right to wear religious symbols at different levels of shared membership beliefs

Discussion

Whether and when religious group members should be allowed to wear religious symbols has become a contentious policy issue. As initiatives that restrict religious symbols in the public sphere emerge on the legislative agenda in parts of Europe and North America, the extent to which restrictions on religious symbols perpetuate intergroup inequality is an important avenue of research for social scientists and policy practitioners alike. This research raises concerns about the biased nature in which members of the public oppose individuals' right to wear religious symbols in various institutional and public settings based on their group membership. The present study also offers insight into the possible sources of this “accommodation gap” that results in weaker support for the rights of religious minority groups, especially Muslims.

Public opinion research on attitudes toward religious symbols has highlighted the role of political ideology and values in explaining different policy attitudes (Bilodeau et al. Reference Bilodeau, Turgeon, White and Henderson2018; Turgeon et al. Reference Turgeon, Bilodeau, White and Henderson2019), with less attention paid to the intergroup dynamics of religious accommodation beyond measures of prejudice. Minority religious practices, including the wearing of overt religious symbols, may trigger perceptions of cultural distance and a weaker sense of shared membership in the larger national community. This weaker perceived commitment to the nation can inhibit majority group members from supporting the civic and political rights of minorities (Hindriks et al. Reference Hindriks, Verkuyten and Coenders2015; Verkuyten and Martinovic Reference Verkuyten and Martinovic2015), extending social welfare benefits to minorities (Harell et al. Reference Harell, Banting, Kymlicka and Wallace2021), and affect support for various diversity policies, including immigration (Reeskens and Van der Meer Reference Reeskens and van der Meer2019), refugee resettlement (De Coninck and Matthijs Reference De Coninck and Matthijs2020) and citizenship (Politi et al. Reference Politi, Roblain, Gale, Licata and Staerklé2020). Using data from a novel survey experiment conducted across Canada, the results presented here show that considerations about national membership also influence support for the right to wear religious symbols and are particularly influential in judgments about the rights of Muslims across different settings.

The present research makes several contributions to the literature on public attitudes toward religious symbols. First, the data show that the stereotypes individuals hold about how committed Christians, Muslims, and “religious minorities” more generally are to the national community differ, especially with respect to their perceived national identification. As a group, Christians are judged as especially committed Canadians who are perceived as identifying more strongly with the nation than the average Canadian. On the other hand, Muslims in particular, but religious minorities more generally, suffer a “membership penalty” as they are stereotyped as much less committed and identified than the average Canadian. Second, the research shows that considerations about how these different religious groups are perceived to relate to the national community have an important influence on individuals' support for the right to wear religious symbols. While this is true regardless of the group in question, national membership considerations are especially important for the acceptance of Muslim religious symbols.

As others have noted (Banting et al. Reference Banting, Kymlicka, Harell, Wallace, Gustavsson and Miller2019; Harell et al. Reference Harell, Banting, Kymlicka and Wallace2021), perceptions of group members' commitment and contribution to the nation are relevant predictors of social policy preferences like support for inclusive redistribution. The present research finds that such membership considerations extend beyond welfare attitudes to influence more symbolic issues such as support for the right to wear religious symbols. Disparities in support for the rights of certain religious minorities to wear religious symbols are driven in part by a failure to recognize individuals from these communities are committed members of the nation. Beyond these membership considerations, other factors tied to social inequality, including SDO and empathy, are also associated with public acceptance of religious symbols. This research extends previous work by demonstrating that considerations about national membership operate differently depending on the group in question and, independent of other demographic and psychosocial variables, are predictive of support for the right to wear religious symbols. Evidently, the influence of these membership considerations is not limited to institutional settings, such as when studying in public schools and universities or when working as government employees. Indeed, such membership considerations also apply to benign aspects of one's daily life, such as when walking in public on the streets, raising concerning questions about the encroachment of motivations behind supposedly secular policy proposals into individuals' personal lives.

The research is, of course, not without limitations and offer avenues for future research to further examine how national membership boundaries and other social perceptions affect judgments about religious accommodations. The research presented here examined perceptions and reactions to a limited number of religious groups based on a question-wording experiment. While this focused approach is necessary in light of the amount of data available and the potentially large number of comparisons that could be made, more work is needed to nuance our understanding of social perceptions and their policy implications for a wider array of religious groups and practices. First, the research emphasized one specific aspect of religious accommodation: judgments about the rights of others to wear religious symbols in institutional and public settings. As other work has shown, moral considerations are also important for judgments about the acceptance of different religious practices (Van der Noll et al. Reference Van der Noll, Saroglou, Latour and Dolezal2018; Hirsch et al. Reference Hirsch, Verkuyten and Yogeeswaran2019). Participants were also tasked with making judgments about one of three broad religious groups which does not allow an investigation into important differences that exist within these religious communities, such as the effect of priming specific religious symbols or to disentangle considerations about religious practices from considerations and the various ways religion, race, and gender intersect to influence social perceptions and policy preferences (e.g., Selod and Embrick Reference Selod and Embrick2013; O'Neill et al. Reference O'Neill, Gidengil, Côté and Young2015). Such questions present an important avenue for future research to examine these dynamics across a range of religious practices involving a wider variety of religious groups.

Future research could also expand on the present work by more directly comparing evaluations of different religious groups to one another, examining membership perceptions toward a range of social groups, and by developing and evaluating interventions designed to overcome intergroup biases. Commitment to the nation is conceptualized here with respect to the country-level, asking respondents to make judgments about different religious groups' commitment to Canada, “relative to other Canadians.” This approach leaves unanswered meaningful questions about commitment to other political, regional, or social groups, namely the Quebec national community. Finally, future research aimed at mitigating the persistent inequalities in support for the rights of religious minorities may benefit from interventions aimed at overcoming the stereotype that Muslims and other religious minorities are less committed to the national community. As the data presented here suggest, such interventions should not only target identity-based considerations but also target broader perceptions of the concerns and commitments religious minorities have toward others in the national community. Finally, while the data are weighted to improve generalizability to the Canadian population in terms of age, gender, province of residence, and language, the sample is not representative in terms of other variables, notably the religious background of respondents.

With these caveats in mind, the research makes a contribution by advancing existing work around religious accommodation and the rights of religious minorities. It is argued that support for religious symbols is driven in part by the extent to which the group in question is perceived as committed to the national community, a judgments which is especially pertinent for decisions about supporting religious minority rights. The research extends previous work by showing how perceptions of other's commitment to the nation, a factor which underpins support for inclusive redistribution (Harell et al. Reference Harell, Banting, Kymlicka and Wallace2021), is also a strong motivator behind the acceptance of religious symbols. The data also show how cueing considerations about Muslims invokes greater distancing from the Canadian national community compared to cueing a generic label of “religious minorities” and that the influence of considerations of national membership on acceptance of religious symbols varies across target religious groups in meaningful ways. In sum, the data presented here showcase how generalizable perceptions of other's commitment and membership in the national community are for supporting minorities.

Conclusions

Perceptions of the commitment of different minority groups to the nation have been shown to be an important consideration for extending redistributive supports to minority communities (Harell et al. Reference Harell, Banting, Kymlicka and Wallace2021). The literature on religious accommodation, however, has not examined the social perceptions of others' shared identity, commitment, and contribution to the national community as an important factor that motivates support for religious tolerance and accommodation. This research examines the question of who is seen to belong to the national community, not just in terms of their perceived identification with the nation, but also their relative commitment and contribution to the national community. Compared with more traditional religious groups like Christians, religious minorities, and Muslims in particular, are especially likely to cue considerations that undermine their perceived commitment to the wider national community, which in turn has important implications for supporting their right to wear religious symbols. However, when individuals affirm the national commitment of religious minorities, the gap in support for the rights to wear religious symbols can close, and, in the case of Muslims, even reverse directions.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048322000141

Acknowledgement

The author wishes to acknowledge the generous support provided by the Consortium on Electoral Democracy in facilitating this research. An earlier version of this work was presented at the 2021 Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association. The author would also like to thank the conference participants, as well as Dietlind Stolle, Allison Harell, Elisabeth Gidengil, Antoine Bilodeau, and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Conflict of interest

None.

Bibliographical statement: Colin Scott is a postdoctoral fellow at Concordia University's Department of Political Science in Montreal, Canada. His research focuses on the psychology and politics of diversity and is primarily concerned with the adaptation and participation of migrants and the ways in which social perceptions of others influence inclusive attitudes and support for the rights of minority groups.