Introduction

Primary health care, as a basic health guard for the human being, is always taken as the basis of a good health strategy or policy in China with its immense population but limited resources from the ancient times till the present day. Good primary health care can enhance lives and hence the national health statistics and outcomes, low incidence of low birth weight, low rates of poor self-reported health and lifestyle risk factors, and diagnosis and treatment in the early stage of different diseases (Starfield et al., Reference Starfield, Shi and Macinko2005). In recent decades, primary health care has been gradually neglected in Chinese health reform.

Barefoot doctor model is the successful primary health care pattern for those countries with large population and low income. The Barefoot Doctor concept was first introduced by President Mao in 1950s. The title referred to farmers who received between three and six months medical and paramedical training, and so worked in their rural villages to offer primary medical services applying a mix of both Western and Traditional Chinese remedies (China Daily, 2012; Dan and Tai, Reference Dan and Tai2016). The barefoot doctors contributed greatly in the campaigns to fight against Malaria, the ‘big belly’ disease (schistosomiasis, where sufferers are infected during their farming by the worms living in the water of the paddy fields and developed symptoms of permanent damage to organs such as the liver, the bladder and the intestine). They also helped to sharply reduce the child mortality rate (China Daily, 2015a, 2015b). The contributions of the barefoot doctors remarkably improved the health status among China’s rural residents through the provision of low cost and locally suitable services (Blumenthal and Hsiao, Reference Blumenthal and Hsiao2005). During the 1980s, the barefoot doctor medical pattern was gradually dismantled when a change of policy was introduced away from primary health care to hospital-based care (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Gusmano and Cao2011). Without an adequate support from those responsible for setting official policy, the barefoot doctor system in China has diminished, in middle 1980s, some barefoot doctors became the village doctors, and others remains the barefoot doctors. In 2003, the number of barefoot doctors reduced from 2.4 million(including the village doctors) in 1985 to about 0.79 million.

In recent Chinese health reports and statements of official health policy, the government has re-stressed the importance of primary health care, adopted the tiered service delivery system, and tried to return to a greater reliance upon primary health care services. Alas, we believe the results so far have not been realized and fall short of a satisfactory result. The government still seems to be overlooking primary health care institutions, and opportunities for promoting primary health care policies have been rare. There remains, therefore, an imbalanced and perhaps inappropriate degree of investment between the primary health care institutions and secondary hospitals. This why we highlight the importance and the urgency of primary health care service improvement and hope the Chinese government would acknowledge the imbalance and develop more decisive, effective and financed policies that are still suitable to the real needs of the people from primary health care.

Primary health care in China

Since 1949, when the People’s Republic of China was founded, right up to the 1970s, it has been the responsibility of the Chinese government to support and finance the basic health care service and hospitals. In those days people had access to the subsidized health clinics that were run by ‘barefoot doctors.’ This primary health care, free of charge to the people, was an important factor in doubling the country’s average life expectancy from 35 in 1949 to 68 in 1978 (China Daily, 2011). But after the 1980s the government changed its health policies and brought in the idea of the free-market economy, which caused a number of basic care service institutions and first-tier hospitals to go bankrupt and the barefoot doctor system to gradually reduce (Juan et al., Reference Juan, Xiaoqin, Yadong, Shuqi, Aimin, Donald and Wei2012). In China, there is a three-tier health and medical care system for providing health services. However, in recent times, the Chinese Government’s official health services have been mainly provided by the tertiary and secondary health care hospitals. The result has been that the role of primary health care seems to have been ignored or overlooked.

As is well known, China is a big country with a population of about 1.5 billion men, women and children, who between them represent about 18% of the world’s population. Of this number, 54.77% are urban dwellers and the remaining 45.23% live in rural areas. This means that the rural residents still constitute a substantial part of China’s total population. Most of the rural residents live in remote and poor villages. It is therefore very difficult for them to get access to adequate and convenient medical services under the current health care system. Even though the recent noteworthy medical insurance project has greatly relieved the pressure of huge medical expenditure, the total medical expenditure for rural residents remains unaffordable mainly because of the high expenses in transportation and accommodation, and also the expenses of their relatives who often need to accompany the patients. The same financial problem is faced by urban residents, and the consequences are even more serious. Between 1998 and 2003, a survey conducted by the National Health Service showed that the proportion of patients not seeking health care for financial reasons increased both in rural and urban areas (China Ministry of Health, 2010). Without adequate physicians and medical facilities in the community hospitals, more and more urban residents prefer to go to the big hospital centers irrespective of the nature of the disease they have. Whatever their indisposition, they only seem to trust the medical skills of physicians in big hospitals, which only lead to a waste of the medical resources of those big hospitals because they are being diverted away from planned high-level medical interventions to lower level care that should be undertaken elsewhere.

With the development of the economy and the change of social demographic epidemiology, China now has been challenged by the increasing number of elderly people and the increase in incidence of non-communicable disease (NCD) (Yuanli et al., Reference Yuanli, Gonghuan, Yixin and Richard2013). With a dramatic increase of NCDs, the data shows that NCDs are the main cause of mortality around the world, and NCDs accounted for an estimated 86.6% of all deaths in China in 2013 (World Health Organization, 2013; National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China, 2015). Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (CCVD), cancer (lung cancer) and chronic respiratory diseases are three leading causes of the NCD burden. For patients having NCDs, the effective screening and treatment in early stages at primary health care levels could highly improve the survival rate and the quality of life of those affected and their close family.

The lack of primary health care not only make patients unwilling to seek health care, but also causes the deterioration of doctor–patient relationships. There is an increasing problem of trust at primary health care level: patients do not trust their primary health care doctors, and sometimes there is violence against physicians and nurses. For Chinese doctors, they are too busy to have an effective communication with their patients. It is not uncommon for a specialist to see around 100 patients daily in the outpatient department of a big hospital. The time spent with each patient is therefore very limited – usually to < min (Qi and Peng, Reference Qi and Peng2013). With the rapid growth in the variety and quality of health diagnosis and treatment processes over the past 20 years, patients have inevitably raised their own expectations and demands. They now hold higher degrees of skepticism toward the doctors and the diagnoses they offer and there is a growing number of complaints, and malpractice lawsuits (Broom, Reference Broom2005; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Vargas, Núñez and Macchiavello2011). Given this, the government is increasingly aware of this problem, the reform for the training of Family Physicians (the 5+3 program) proposed to improve the primary health care and ease the contradictions and conflicts in Chinese health care system.

The Chinese government made efforts to improve the health care and medicine system in China, including impressive achievements in health care reform and rapid progress toward universal health coverage. In 2009, ensuring the whole nation enjoys access to basic medical services and primary health care was stressed in ‘Opinion on Deepening Reform of the Medical and Health Care System’ (Lu, Reference Lu2012). In face of the current situation in Chinese health indicators, China needs to further reform its health system with a number of critical steps to meet the growing health needs of the growing population and minimize or remove the contradictions between service delivery options. The government issued and tried to establish a referral system in China aiming to strengthen the medical service capabilities of primary health care, and thus relieve the current pressure of the second- and third-tier hospitals.

However, the Government’s efforts do not seem to be leading yet to a completely successful outcome for the current imbalance of investments which still exists between higher level hospitals (general hospitals, general hospitals specialized in Traditional Chinese Medicine, and specialized hospitals) and the grass-root level health care institutions (community health service centers, urban health centers, township health centers, village clinics and outpatient department). From 2000 to 2014, the total number of hospitals in China has increased from 16318 to 25 860, which shows a marked rise in number and a high-value investment by government, while the number of grass-root level health care institutions has decreased from 1 000 169 in 2000 to 917 335 in 2014 (Figure 1) (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2015).

Figure 1 The number of grass-root level health care institutions in China Source: Retrieved 24 August 2016 from http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2015/indexeh.htm

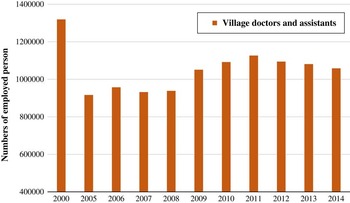

As with the decrease of the grass-root level health care institutions, the number of village clinics shows the same trend in that the village clinics have been reduced from 709 458 to 645 470 from 2000 to 2014. The neglect of development of rural health care has led to a brain drain of those medically trained to the big cities and the hospitals. The country is struggling to keep rural doctors, as a great number, like barefoot doctors, are increasingly reluctant to stay at their jobs due to barriers such as low pay, low social status and poor career prospects (China Daily, 2015a, 2015b). As the data issued by the National Bureau of Statistics of China shows, the number of Chinese village doctors and assistants has been dwindling from 1 319 357 in 2000 to 1 058 182 in 2014 (Figure 2) (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2015).

Figure 2 The number of village doctors and assistants in China Source: Retrieved 24 August 2016 from http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2015/indexeh.htm

With the dramatic decrease of primary health care institutions and village doctors and assistants, it is now common that the rural resident who has a disease but insufficient financial resources will not see a formally trained medical practitioner of any kind. In China, CCVD and respiratory system diseases are the top two diseases threatening the health condition of rural residents. But most of rural residents did not see a doctor, even if they had been diagnosed as needing treatment as the cost of treatment is too high. The burdening medical costs are not only accounted for transport and accommodation of themselves and relatives to the big hospitals in the cities, as described earlier, but also by the price of medicine and the series of necessary examinations themselves. More and more patients flowing into the big hospitals is one of the main reasons why those doctors experience such a heavy workload. Besides this, most rural residents could not be diagnosed in their early stages of disease by primary centers for these have no basic examination or village doctors to help with the early screening. By the time they have been diagnosed, most of them are in the middle and advanced stages of disease, which therefore could only help to increase the mortality rate and lower the quality of life of rural patients. What is worse, the weak primary health care system drives up higher the rate of NCDs among rural residents, for they have no awareness of disease prevention without enough knowledge, which just make the rural resident’s health and economic condition even worse.

Under such a situation, the Chinese primary health care system is poor in quality, which makes people feel more reluctant to seek health care. Even though Chinese health care and medical service skills have improved greatly and even contribute to the cutting-edge technology in the world. Yet, without adequate primary health care institutions and services, the improvement of medicine could not relieve the pressure of the increased number of patients and the consequential medical expenses. It is therefore imperative that the Chinese government strengthen the primary health care in its health reform and policy-making.

More attention needed

Health reform in China is necessary, but equity and effective execution is a crucial principle within it (Le et al., Reference Le, Xiaoli, Tengfei and Jingmin2015). A part of the current program of health reform in China, the importance of primary health care has been stressed time and again, the leader of China has advocated an improved system and quality of basic medical services so that the public can enjoy accessible and continuous health services which cover prevention, treatment and rehabilitation. He has also stressed that work to ensure people’s health should focus on the grassroots and use reform and innovation to create momentum (National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China, 2016). However, the policy which could really promote the development and improvement of primary health care is rarely discussed or seen in action. Without better policies on finance, human resources and pension, the improvement and strengthening of primary health care is, sadly, just empty talk.

To build a better health care system, which could provide the optimal health care and medical service to the whole nation, we urge the policy-makers to allocate more financial investment, more human resource investment, and better facilities investment, backed up by policies which are favorable to improve and strengthen grass-root level health care institutions. These institutions are the first line of defense and the foundation of all health care in the battle against diseases, the government should drive forward with this commitment and put it into practice.

Acknowledgment

Le Yang is a teacher of Shanxi Medical College for Continuing Education. Her research interests focus on the impacts of food safety management, health policy, health reform and current situation of health care in China.