Introduction and background

The demand for primary care, community care and community nursing services is on the increase due to world demographic changes (World Health Organization, 2008; Maybin, Charles and Honeyman, Reference Maybin, Charles and Honeyman2016; Kroezen et al., Reference Kroezen, Dussault, Craveiro, Dieleman, Jansen, Bucham, Barriball, Rafferty, Bremner and Sermeus2015). The needs of community nursing patients are changing, requiring a new skill mix responsive to local patient and population needs (Drennan and Ross, Reference Drennan and Ross2019; Drennan et al., Reference Drennan, Calestani, Ross, Saunders and West2018; Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Leadbetter, Martin, Wright and Manley2015). The increasing need for community nurses is further confounded by challenges with recruitment and retention of nurses with the World Health Organization reckoning it is nearing a universal challenge (World Health Organization, 2016, 2020).

One in three adults in developed countries have multiple long-term conditions; this is predicted to double by 2035 (Hajat and Kishore, Reference Hajat and Kishore2018). By 2050, there will be a global increase in nursing demand due to an ageing population, in both developed and developing countries (United Nations, 2015). As nursing home placements are costly, patients are increasingly opting to be nursed at home to mitigate such costs (Maurits et al., Reference Maurits, de Veer, van der Hoek and Francke2015a). In most countries, a good death is defined by people dying in a place of their choice whilst receiving optimal care; this has become a social and political priority (Sines et al., Reference Sines, Aldridge-Bent, Fanning, Farrelly, Potter and Wright2013; Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, McCrone, Hall, Koffman and Higginson2010; Reed, Fitzgerald and Bish, Reference Reed, Fitzgerald and Bish2018) and most people in both developed and developing nations are opting to die at home in the comfort of family and friends whilst receiving community nursing care.

Governments are urging for the provision of care closer to home (Edwards, Reference Edwards2014; NHS England, 2015; Reed, Fitzgerald and Bish, Reference Reed, Fitzgerald and Bish2018; Aiken et al., Reference Aiken, Sloane, Bruyneel, Van den Heede, Griffiths, Busse, Diomidous, Kinnunen, Kozka, Lesaffre, McHugh, Moreno-Casbas, Rafferty, Schwendimann, Scott, Tishelman, Achterberg and Sermeus2014) based on a recognition that quality and evidence-based healthcare in the community can be cheaper than hospital care (Kraszewski and Norris, Reference Kraszewski and Norris2014; Dickson, Gough and Bain, Reference Dickson, Gough and Bain2011; Maybin, Charles and Honeyman, Reference Maybin, Charles and Honeyman2016; Naruse et al., Reference Naruse, Taguchi, Kuwahara, Nagata, Watai and Murashima2012). However, in England, nursing workforce shortage is a greater challenge to community nursing healthcare provision than funding (The Health Foundation, The King’s Fund and the Nuffield Trust, 2018) making it difficult to meet such demands.

The English adult community nursing workforce is diverse and made up of different roles (NHS England, 2015). For example, community matrons, specialist nurses, registered general nurses and district nurses to name a few. District nurses have an additional specialist qualification to being a general registered nurse and, in most cases, they hold a team leader role (Queen’s Nursing Institute [QNI], 2015). Between 2010 and 2017, district nurses have declined by approximately 45% with an average vacancy rate of 21% (Stephenson, Reference Stephenson2015; Nuffieldtrust, 2017; Marangozov et al., Reference Marangozov, Huxley, Manzoni and Pike2017). This is further precipitated by most district nurses retiring and an underfunding of the specialist qualification (QNI, 2015). In 2014, 35% of adult community nurses were above the age of 50 years, in comparison to 23.6% of hospital nurses, with both groups planning on retiring within a decade (Royal College of Nursing [RCN], 2012; Ball et al., Reference Ball, Philippou, Pike and Sethi2014).

Community nurses’ scope of practice is hospital avoidance and an improved quality of life for those with long-term conditions, palliative care for those at the end of life who are housebound (Drennan, Reference Drennan2018). Community nurses are currently employed by different organisations, the government through the National Health Service (NHS), charitable organisations, private sector and community interest companies (QNI, 2014; Maybin et al., Reference Maybin, Charles and Honeyman2016). Historically, community nursing services were a single entity provision being provided by district nurses. However, with population changes and disease, progression models aimed at addressing the changes in demand have resulted in new models of care being designed. For instance, in February 1996, community-integrated care teams were introduced, and in September, the same year rapid response teams were introduced (Audit Commission, 1999). These two services aimed at having a group of therapists (nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social workers and doctors) working as one team from the same office providing a hospital avoidance service. To date, other models of care such as the @home service, a highly specialised service staffed by highly skilled clinicians aimed at hospital avoidance (hospital at home), by administering therapies and requesting tests which are usually accessible in a hospital setting, has been designed (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Pickstone, Facultad and Titchener2017). In addition to the above, Buurtzorg model (originated from the Netherlands) has been evaluated across the country (Drennan et al., Reference Drennan, Calestani, Ross, Saunders and West2018). The Buurtzorg model evolves around small teams of nursing staff providing a range of personal care, social and clinical care to people in their own homes in a neighbourhood (a smaller area to the one being currently covered by community nurses). Thus, indicating possible future changes to current community nursing service provision.

Methods

The aim of this integrative literature review was to answer: ‘What are the factors that present challenges to community healthcare organisations in recruiting and retaining registered nursing staff into adult community nursing teams?’

Search strategy

A search on PROSPERO database was conducted to establish there were no similar ongoing reviews. The protocol for this review can be found on PROSPERO (registration number CRD42018086197). The databases CINAHL Complete, WEB of Science, MEDLINE, and PROQUEST were used as some of the best electronic databases for supporting nursing-related literature searches which are, based on wide coverage of journals, widely used and also covering biomedical literature (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Jacobs and Levy2006). Citation review and snowball approach were applied to identify papers that may have used unusual terms within the inclusion criteria.

Population, Exposure/Outcomes (PEO) underpinned the research question and search terms as it sought to understand a phenomenon, which could have been answered using quantitative or qualitative approach (Bettany-Saltikov, Reference Bettany-Saltikov2012). The search terms chosen to answer the review question are presented in Table 1; both search terms and search process were guided by a subject librarian.

Table 1. Search terms

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The search was restricted to 10 years to maintain a comprehensive yet contemporary review (January 2008–December 2018). Selected studies were peer-reviewed empirical research looking at community nursing for adult patients (over 18 years of age). Studies which looked at community nursing as a subset of other nursing fields were also included due to a dearth solely focusing on community nursing as an independent cohort. All studies were published in English from high- to middle-income countries with a community nursing service comparable to the English community nursing service. As the review process accessed international literature, nurses included were registered nurses of any role licensed to provide community nursing care (in peoples’ homes) to adult patients with physical health needs. Opinion papers, editorials, secondary research, commentaries and studies funded by charitable organisations were excluded due to the potential risk of bias.

Study selection, data extraction and quality appraisal

Title and abstract reviews were conducted by EC and JD. JL mediated any study disputes between EC and JD. All the authors reached consensus on all papers which were appropriate for a full-text review and inclusion. Details of the papers selected are shown in the adapted Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flowchart (Figure 1) (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). In total, 1106 subject-related papers were identified as shown in Figure 1, and these were downloaded to Refworks® from each database for record keeping and further analysis. After the removal of duplicates, most of the papers did not meet the inclusion criteria by title (as they were either opinion papers, editorials or not inclusive of adult community nursing or, primary care in general). The remaining papers were reviewed by abstract and 95 did not meet the inclusion criteria as they were non-empirical studies and or irrelevant to this review in terms of focus, which left 27 papers for full-text review against the inclusion criteria, from which only 10 papers were selected. Data extraction included author, aims, location, design, findings and quality appraisal exceptions. The Center for Evidence-Based Management (CEBMa, 2014) critical appraisal of survey and qualitative research tools were used for quality appraisal (Table 2).

Figure 1. Process of paper selection – adapted PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 2. Study characteristics

Analysis

An integrative literature review approach was chosen as it permits the inclusion of empirical studies conducted with varied methodologies (Whittemore and Knafl, Reference Whittemore and Knafl2005). Specifically, qualitative, and quantitative using different methods, without following a rigorous systematic process on inclusion papers. Data were extracted according to the review question and a Cochrane narrative synthesis was employed as the method of data analysis as it is a robust and systematic method (Ryan, Reference Ryan2013; Snilstveit et al., Reference Snilstveit, Oliver and Vojtkova2012).

Results

From the selected 10 empirical studies, 3 were from the Netherlands and there was 1 study conducted in each of the following countries: Canada, United States, China, Australia, Japan and England. The tenth paper included was from Europe including eight countries (the Netherlands, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Slovakia). All but one of the studies were surveys, the exception being focus group interviews.

Synthesis of results and emergent themes

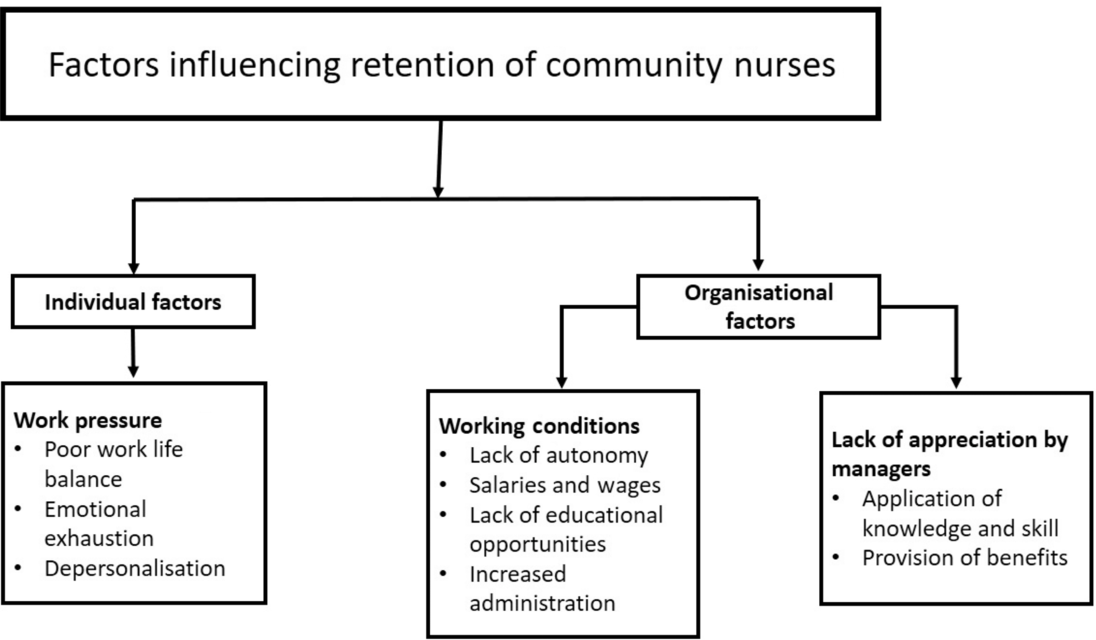

There were no studies found relating to the recruitment of community nurses. Yet, there were 10 reviewed studies focusing on factors which influence retention of community nurses, with emergent and recurring individual and organisational themes that were then selected for synthesis. They were identified by similarities, before being clustered together, either as a main theme or a subtheme as shown in Figure 2. The three key themes were (1) work pressure, (2) working conditions and (3) lack of appreciation by managers. Each will be discussed along with the included subthemes.

Figure 2. Themes and subthemes from the reviewed literature.

Individual factors

Work pressure

Eight studies identified work pressure (caseload and workload) as a factor that influences the decision for community nurses to remain or leave employment (Maurits et al., Reference Maurits, de Veer, van der Hoek and Francke2015b; Estryn-Behar et al., Reference Estryn-Behar, van der Heijden, Fry and Hasselhorn2010; Ellenbecker et al., Reference Ellenbecker, Porell, Samia, Byleckie and Milburn2008; Tummers et al., Reference Tummers, Groeneveld and Lankhaar2013; Storey et al., Reference Storey, Cheater, Ford and Leese2009; Halcomb and Ashley, Reference Halcomb and Ashley2016; Naruse et al., Reference Naruse, Taguchi, Kuwahara, Nagata, Watai and Murashima2012). In one study, 60–70% of nurses identified work pressure as an important factor that would influence their decision to leave employment (Estryn-Behar et al., Reference Estryn-Behar, van der Heijden, Fry and Hasselhorn2010). It is worth noting that this study included nurses from other fields of nursing not only community nurses and it was not possible to disaggregate responses. However, this argument was also supported two other studies (Ellenbecker et al., Reference Ellenbecker, Porell, Samia, Byleckie and Milburn2008; Tourangeau et al., Reference Tourangeau, Patterson, Rowe, Saari, Thompson, Macdonald, Cranley and Squires2014), which focused only on community nurses. Both the authors argued that a reduction in stress and work pressure supports nurse retention. Storey et al. (Reference Storey, Cheater, Ford and Leese2009) found caseload pressure linked to early retirement of community nurses who are nearing their retirement age. Participants in one study said they would prefer a lighter workload rather than retire (Storey et al., Reference Storey, Cheater, Ford and Leese2009). The same study found 36% of participants identified staff shortages and increased workload as precipitating factors towards early retirement from community nursing. However, staff retirement is a by-product of staff being overwhelmed nothing to do with recruitment and retention. Unsurprisingly, increased work pressure correlated with reduced occupational commitment and subsequent negative job satisfaction, impacting on patient safety and quality of service being provided (Maurits et al., Reference Maurits, de Veer, van der Hoek and Francke2015a). Similarly, study participants in Halcomb and Ashley’s (Reference Halcomb and Ashley2016) study felt rushed and spending less time as desirable with patients. As rightly pointed out by Naruse et al. (Reference Naruse, Taguchi, Kuwahara, Nagata, Watai and Murashima2012), 30% of community nurses experience time pressure frequently due to workload, which results in higher levels of emotional exhaustion.

Poor work–life balance

Community nurses were found to be dissatisfied with their work–life balance with challenges in meeting work and family demands in four studies (Storey et al., Reference Storey, Cheater, Ford and Leese2009; Tourangeau et al., Reference Tourangeau, Patterson, Rowe, Saari, Thompson, Macdonald, Cranley and Squires2014; Estryn-Behar et al., Reference Estryn-Behar, van der Heijden, Fry and Hasselhorn2010; Naruse et al., Reference Naruse, Taguchi, Kuwahara, Nagata, Watai and Murashima2012). From focus groups conducted by Tourangeau et al. (Reference Tourangeau, Patterson, Rowe, Saari, Thompson, Macdonald, Cranley and Squires2014), community nurses reported of working from home after hours, with the process being described as stressful, characterised by paperwork to be completed and order of supplies. Eighty-eight per cent of participants in a study by Naruse et al. (Reference Naruse, Taguchi, Kuwahara, Nagata, Watai and Murashima2012) reported of insufficient rest time. Conversely, Estryn-Behar et al. (Reference Estryn-Behar, van der Heijden, Fry and Hasselhorn2010) note starting a family and caring for a family member are challenges associated with achieving a work–life balance, especially for those with full-time contracts.

Emotional exhaustion

A study by Hai-Xia et al. (Reference Hai-Xia, Li-Ting, Feng-Jun, Yao-Yao, Yu-Xia and Gui-Ru2015) defined community nursing associated with emotional exhaustion as a situation, where community nurses cannot easily address challenges they are facing at work. These challenges were reported to be a result of work environment and workload, which will result in perceived time pressure and job burnout, leading to staff turnover, due to decreased job satisfaction and lack of professional pride (Naruse et al., Reference Naruse, Taguchi, Kuwahara, Nagata, Watai and Murashima2012; Hai-Xia et al., Reference Hai-Xia, Li-Ting, Feng-Jun, Yao-Yao, Yu-Xia and Gui-Ru2015). Emotional exhaustion as a reason for leaving employment in over 50% of participants (Estryn-behar et al., Reference Estryn-Behar, van der Heijden, Fry and Hasselhorn2010) and Hai-Xia et al. (Reference Hai-Xia, Li-Ting, Feng-Jun, Yao-Yao, Yu-Xia and Gui-Ru2015) observed a positive relationship between married community nurses and emotional exhaustion. As married community nurses presented with a higher score of emotional exhaustion in comparison to their unmarried counterparts, this highlights family life as a significant factor that can influence community nurses’ decision-making in relation to remaining employed.

Depersonalisation

A study by Hai-Xia et al. (Reference Hai-Xia, Li-Ting, Feng-Jun, Yao-Yao, Yu-Xia and Gui-Ru2015) reported depersonalisation to be (the adoption of negative and indifferent attitudes towards others) positively correlated with job burnout. And Naruse et al., (Reference Naruse, Taguchi, Kuwahara, Nagata, Watai and Murashima2012) found that community nurses who perceive job-related time pressure are likely to experience a higher level of depersonalisation. Time pressure is felt by community nurses at patients’ homes and during commuting with 95% reporting of anxiety during home visits (Naruse et al., Reference Naruse, Taguchi, Kuwahara, Nagata, Watai and Murashima2012). Emotional exhaustion, poor work–life balance and depersonalisation are positively correlated (Hai-Xia et al., Reference Hai-Xia, Li-Ting, Feng-Jun, Yao-Yao, Yu-Xia and Gui-Ru2015; Naruse et al., Reference Naruse, Taguchi, Kuwahara, Nagata, Watai and Murashima2012).

Organisational factors

Working conditions

In a cross European study with participants from different nursing fields, including community nurses, the main and most frequent reason for leaving an organisation was poor working conditions (Estryn-Behar et al., Reference Estryn-Behar, van der Heijden, Fry and Hasselhorn2010). A poor work atmosphere was the second highest ranked motive for people to leave employment; conducive working conditions enhance an organisation’s ability to retain community nursing workforce (Tummers et al., Reference Tummers, Groeneveld and Lankhaar2013). The nature of these working conditions was not defined. Conversely, a positive work atmosphere including pleasure at work, good team spirit and collegiality was found necessary for community nurses’ retention (Tummers et al., Reference Tummers, Groeneveld and Lankhaar2013).

Lack of autonomy

Six studies identified community nurses are likely to remain employed if they felt autonomous (empowered/independent) within their roles (Maurits et al., Reference Maurits, de Veer, van der Hoek and Francke2015b; Tummers et al., Reference Tummers, Groeneveld and Lankhaar2013; Maurits et al., Reference Maurits, de Veer, van der Hoek and Francke2015a; Halcomb and Ashley, Reference Halcomb and Ashley2016; Tourangeau et al., Reference Tourangeau, Patterson, Rowe, Saari, Thompson, Macdonald, Cranley and Squires2014; Estryn-Behar et al., Reference Estryn-Behar, van der Heijden, Fry and Hasselhorn2010). Autonomy encourages job satisfaction which promotes staff retention (Maurits et al., Reference Maurits, de Veer, van der Hoek and Francke2015b) and dissatisfaction with a lack of autonomy is a contributing factor towards the decision to leave an organisation (Estryn-Behar et al., Reference Estryn-Behar, van der Heijden, Fry and Hasselhorn2010; Tummers et al., Reference Tummers, Groeneveld and Lankhaar2013). Whilst autonomy was valued, some community nurses found it isolating and stressful (Halcomb and Ashley, Reference Halcomb and Ashley2016).

Salaries and wages

There is some evidence to suggest that nurses employed in Eastern European countries are likely to leave employment due to remuneration in comparison to those in other European countries (Estryn-Behar et al., Reference Estryn-Behar, van der Heijden, Fry and Hasselhorn2010). However, some community nurses felt their low wage rate was mitigated by good working conditions (Halcomb and Ashley, Reference Halcomb and Ashley2016). Some nurses said their salary or wage did not reflect the amount of work and responsibilities of their jobs (Halcomb and Ashley, Reference Halcomb and Ashley2016; Storey et al., Reference Storey, Cheater, Ford and Leese2009). Community nurses earning below a certain threshold are more likely to feel emotionally exhausted and burnout, with a higher intent to leave employment (Hai-Xia et al., Reference Hai-Xia, Li-Ting, Feng-Jun, Yao-Yao, Yu-Xia and Gui-Ru2015). Salaries and wages were used as some of the studies had participants on a monthly salary, whilst others had a wage paid based on the hours worked per week.

Lack of educational opportunities

Educational opportunities (career opportunities/personal development) were identified as important factors in retaining community nurses in five studies (Estryn-Behar et al., Reference Estryn-Behar, van der Heijden, Fry and Hasselhorn2010; Tummers, Groeneveld and Lankhaar, Reference Tummers, Groeneveld and Lankhaar2013; Maurits et al., Reference Maurits, de Veer, van der Hoek and Francke2015b; Halcomb and Ashley, Reference Halcomb and Ashley2016; Storey et al., Reference Storey, Cheater, Ford and Leese2009). In a study by Halcomb and Ashley (Reference Halcomb and Ashley2016), most participants were dissatisfied with access to education and training, leading to staff turnover. Development and career opportunities are important for retaining workforce in community nursing (Estryn-Behar et al., Reference Estryn-Behar, van der Heijden, Fry and Hasselhorn2010). In contrast, Maurits et al. (Reference Maurits, de Veer, van der Hoek and Francke2015b) argue a lack of educational opportunities alone is not directly significant for staff turnover. However, combined with other factors, it increases one’s likelihood of leaving employment. This is also evidenced by Storey et al. (Reference Storey, Cheater, Ford and Leese2009) where community nurses nearing retirement were happy to take early retirement as they felt, there were no further educational opportunities; they had reached the ‘ceiling’ of their career.

Increased administration

Four studies identified community nurses’ administration (paperwork) as a risk factor that has a negative impact on workforce retention (Halcomb and Ashley, Reference Halcomb and Ashley2016; Storey et al., Reference Storey, Cheater, Ford and Leese2009; Tourangeau et al., Reference Tourangeau, Patterson, Rowe, Saari, Thompson, Macdonald, Cranley and Squires2014; Naruse et al., Reference Naruse, Taguchi, Kuwahara, Nagata, Watai and Murashima2012). Over 90% of participants who took part in the community nurses’ job burnout study (Naruse et al., Reference Naruse, Taguchi, Kuwahara, Nagata, Watai and Murashima2012) felt overloaded by paperwork. Similarly, Tourangeua et al. (2014) and Storey et al. (Reference Storey, Cheater, Ford and Leese2009) identified issues not only with the quantity of community nurses’ paperwork but also how this had to be done in their own time with no remuneration and duplication of effort in having to paper then electronic records.

Lack of appreciation by managers

Four studies identified a lack of appreciation (recognition) by managers as a motive for community nurses to consider leaving employment (Halcomb and Ashley, Reference Halcomb and Ashley2016; Tummers, Groeneveld and Lankhaar, Reference Tummers, Groeneveld and Lankhaar2013; Storey et al., Reference Storey, Cheater, Ford and Leese2009; Maurits et al., Reference Maurits, de Veer, van der Hoek and Francke2015b). Occupational commitment, job satisfaction and staff retention are positively linked to appreciation by managers Maurits et al. (Reference Maurits, de Veer, van der Hoek and Francke2015b), Although, Tummers et al. (Reference Tummers, Groeneveld and Lankhaar2013) found appreciation by managers had a modest but nonetheless important impact on community nursing retention. Nurses feeling particularly undervalued, especially when being managed by non-clinicians as they believed they had no understanding of their work (Halcomb and Ashley, Reference Halcomb and Ashley2016. Similarly, Storey et al. (Reference Storey, Cheater, Ford and Leese2009) found job satisfaction diminishes when there is a lack of appreciation by managers.

Application of knowledge and skill

Two studies identified community nurses were dissatisfied when they were unable to use of their competencies and this influenced their decision to consider leaving employment (Estryn-Behar et al., Reference Estryn-Behar, van der Heijden, Fry and Hasselhorn2010, Tourangeau et al., Reference Tourangeau, Patterson, Rowe, Saari, Thompson, Macdonald, Cranley and Squires2014). The application of knowledge and skill with a variety of patients is essential to job satisfaction and retaining community nurses (Tourangeau et al., Reference Tourangeau, Patterson, Rowe, Saari, Thompson, Macdonald, Cranley and Squires2014).

Provision of pension and benefits

A good exit pension was a factor influencing the retention of community nursing staff who are nearing retirement, though few nurses understood their pension options (Storey et al., Reference Storey, Cheater, Ford and Leese2009). The pension was not enough to the remaining in the workplace, other factors such as an opportunity for reduced working hours and workload were also important.

Discussion

Our exploration of literature identified a multitude of factors which influence the retentions of nurses as highlighted above at both individual and organisational level. Interestingly, the World Health Organization (2020) suggests that in some situations, nurse retention can be solved by improving salaries, specifically pay equity, working conditions with developmental opportunities and lastly enabling nurses to work to the full extent of their scope of practice. Some of these factors have already been identified as influencing factors towards the retention of community nurses as shown above. However, drawing from the wider literature, a number of studies have considered why hospital nurses leave employment and many of these studies cite job satisfaction (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Barriball, Zhang and While2012), effectiveness of nurse managers (Halter et al., Reference Halter, Pelone, Boiko, Beighton, Harris, Gale, Gourlay and Drennan2017), staffing levels (Hairr et al., Reference Hairr, Salisbury, Johannsson and Redfern-Vance2014), work autonomy and collegial relationships (Duffield et al., Reference Duffield, Roche, Homer, Buchan and Dimitrelis2014) as influencing factors. No doubt, some of these factors mirror those highlighted above. However, contextual differences should be considered when analysing these factors. As the setting or the context may have an influence on the level of resilience for the nurse.

Community nurses as autonomous practitioners, in most cases, they are lone workers, working in isolation and this may influence their decision-making. For example, one significant difference for community nursing compared with hospital nursing is the nurse–patient ratio related to safe staffing levels and its impact on capacity modelling (Keller et al., Reference Keller, Dulle, Kwiecinski, Altimier and Owen2013; Hairr et al., Reference Hairr, Salisbury, Johannsson and Redfern-Vance2014). A hospital ward has a manageable flow of patients usually with the same levels of acuity, and the ward can control the number of admissions which means the nurse–patient ratio can be managed; this is not the case in community nursing and there is no provision of establishing a nurse–patient ratio (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Wright and Martin2016). Thus, putting more demand on community nurses not only based on skill mix but an expectation to be able to manage all patients with varying levels of acuity. As a result, community nurses become task-focused to complete a task, or in some cases, patient visits are reassigned to another day, impacting on continuity of care (Maybin et al., Reference Maybin, Charles and Honeyman2016) and such practices do influence one’s decision to remain employed (RCN, 2018). It is recommended that patient acuity and skill mix are considered when addressing nursing workforce issues (Tevington, Reference Tevington2011; Hairr et al., Reference Hairr, Salisbury, Johannsson and Redfern-Vance2014). This results in increased work pressure on community nurses, which will negatively impact on their work–life balance, resulting in poor emotional well-being and may result in depersonalisation.

Despite some of the nurse retention factors being similar between hospital and community nursing, the supply and demand of nurses is a challenge for both sectors (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Pickstone, Facultad and Titchener2017) with a huge impact on community nursing. As community nursing is a subset of the nursing workforce after hospital nursing, competing for the same supply of nurses (Drennan et al., Reference Drennan, Halter, Grant, Gale, Harris and Gourlay2015). Furthermore, in England, there has been a steady decline of community nurses between 2008 and 2018, equivalent to one in three and this decline is currently estimated at 37% (Rolewicz and Palmer, Reference Rolewicz and Palmer2019). Therefore, the presentation of similar retention factors to an already depleted workforce will have different implications between hospital and community nursing workforce. It is worth noting economies of scale which are enjoyed by most hospital trusts have an influence on how much extra administrative workload is done by nurses related to caring. This is based on differences in their funding and contractual obligations. As hospitals can either specifically create nursing roles to address such workloads, which may be a luxury for community nursing organisations, given the reduction in the pool of staff they can recruit from and financial commitments (Everhart et al., Reference Everhart, Neff, Al-Amin, Nogle and Weelch-Maldonado2013; Beech et al., Reference Beech, Bottery, Charlesworth, Evans, Gershlick, Hemmings, Imison, Kahtan, McKenna, Murray and Palmer2019).

The English nursing register indicates that nurses leave employment before the age of retirement, due to alternative career opportunities, which may attract flexibility and better working conditions (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2017) and these factors have been identified here too. In addition to this, nurses have been reported of using the profession as ‘stepping stone’ (McCrae et al., Reference McCrae, Askey-Jones and Laker2014). This perhaps is related to poor provision of pension and benefits, and remuneration. However, it is unknown how many community nurses and how many hospital nurses have taken this approach or have identified opportunities elsewhere. Overall, literature shows the absence of effective and efficient models considering organisational, professional and personal factors, impinging the development of interventions capable of improving the retention of nursing workforce (Halter et al., Reference Halter, Pelone, Boiko, Beighton, Harris, Gale, Gourlay and Drennan2017).

Current workforce strategies

Evidence suggests that current nursing workforce retention strategies have been mainly focusing on hospital nursing staff, with nothing specific for community nursing, subsequently community nurses are regarded as ‘the invisible workforce’ (QNI, 2009, 2014; RCN, 2013; ). This is not the only flaw, there is also evidence suggesting that these retention models are not co-created with the frontline staff, they are a top-down approach (The King’s Fund, 2014), and in some cases, they are unevaluated and their impact is unknown (Ellenbecker et al., Reference Ellenbecker, Samia, Cushman and Porell2007). For example, in England, a series of measures were put in place in the early 2000s, to date, and it is still unclear if these measures have been a success at retaining staff or if they were even implemented (Halter et al., Reference Halter, Pelone, Boiko, Beighton, Harris, Gale, Gourlay and Drennan2017). Schemes such as workplace nurseries and ‘golden handshakes’ have been implemented to entice nurse to join an organisation and remain employed within the organisation (Drennan et al., Reference Drennan, Goodman, Manthorpe, Davies, Scott, Gage and Iliffe2011; Kleebauer, Reference Kleebauer2016; Jeffrey, Reference Jeffrey2017). In 2017, a national nurse retention initiative was implemented in England with seven steps for organisations to help improve their staff retention (NHS Improvement, 2017).

To address nurse retention, some organisations have developed mentorship/preceptorship schemes, mainly aimed at newly qualified nurses (Forlines, Reference Forlines2018; Camarena, Reference Camarena2018; Sherrod et al., Reference Sherrod, Holland and Battle2020). As a result, nurses have been noted to have improved job satisfaction, thus leading to retention. However, longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of these schemes with staff retention (Camarena, Reference Camarena2018).

In some cases, there are regional disparities in terms of what is being implemented as a way of staff retention. For example, in London, there is the Capital Nurse project aimed at returning student nurses who were trained in London to work in London (Longhurst, Reference Longhurst2016). Therefore, there is a need for the co-creation of community nursing-specific retention strategies which are informed by lived experiences of community nurses to inform policy.

Limitations

There were several limitations associated with this review. First, research on community nursing recruitment and retention, is lacking for the former, scant and diverse for the latter. Second, the heterogeneity of methods, instruments and surveys (and included constructs or items).

Third, we cannot be confident we have captured all studies relating to community nurse retention due to the range of job descriptions and the potential for a range in or job expectations. However, we thoroughly reviewed citations and used a snowball approach to identify other terms or potential papers.

Fourth, the reviewed papers’ quality of included papers was variable. Included papers were mostly surveys offering no more than a snapshot of information and providing no depth of understanding of the issues relating to retention of community nurses or the potential solutions to the problems. As a result, these methodological issues hampered the extent to which conclusions could be drawn.

Fifth, ethical considerations were considered in all but a few studies. However, it is unknown whether the absence of reference to ethics approval represents researchers’ failure to observe the process or failure to report the process.

Future research

Further research exploring both recruitment and retention into community nursing will be able to inform on factors impacting on community nursing recruitment and retention challenges. And this needs to take a qualitative approach, in order to fully explore recruitment and retention factors in detail in comparison to using a predetermined questionnaire, which may not be able to provide detailed information on either individual or organisational influences.

Conclusion

There are multitude of factors which influence community nurses’ retention with a lack of information on recruitment factors, and it is difficult to draw a conclusive argument as some of the factors which influence retention also influence recruitment. From the explored studies, factors influencing retention are context-dependent, co-dependent and vary from one clinician to another, and one country to another.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Fiona Ware, subject librarian and skills advisor at the University of Hull, for her assistance with retrieving some of the reviewed research papers included in this review.

Author contributions

All the authors have agreed on the final version.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.