Introduction

Advances in health information technology have increased patient knowledge and expectations for quality healthcare (Coiera, Reference Coiera2003), obliging service providers to seek new ways of delivering care. It is in this context that public–private partnerships (PPPs) are increasingly being promoted as an effective strategy for responding to patient demands for quality services (Milburn, Reference Milburn2004). Choices about which PPPs to use always involve policymakers making ‘assumptions’ about future healthcare activities that the arrangement may help to improve. Renda and Schrefler (Reference Renda and Schrefler2006) argue that assumptions in PPP activities are intended to make the principal participants more efficient and cost-effective in their activities to improve patient satisfaction.

‘Assumptions’ refer to the contextual factors that have the potential to influence success or failure (Sykes and Dunham, 1995). They are not an integral part of the intervention and therefore not easily controlled by the people involved in its implementation. This aligns with Pawson’s (Reference Pawson2006) view that the progress of any intervention is influenced by the external factors or assumptions that are thought to facilitate progress provided the participants comply in performing their activities. It implies that assumptions in PPP activities are based on the expert opinion of policymakers.

Yet for those in health, there is uncertainty about the extent to which some assumptions facilitate progress toward anticipated health benefits (Pawson, Reference Pawson2006). On one hand, some assumptions may prove to be unrealistic especially if the people involved in implementing the PPP activities are not aware of how they were made. It is also possible that the participants may pay less attention to the activities required to ensure that PPPs achieve their objectives. On the other hand, some assumptions may be realistic in practice provided the participants appreciate the importance of the PPP arrangement and understand what is expected of them in their activities. Depending on their motives or purpose, PPPs for developing healthcare infrastructure have specific assumptions and expectations for participant activities (McKee et al., Reference McKee, Edwards and Atun2006). However, continuous changes in external conditions may make it hard for participants’ to identify which assumptions in their activities are most influential in securing health benefits.

In the United Kingdom, healthcare PPPs are largely driven by government desire to benefit from exploiting private sector resourcefulness in improving the procurement of essential infrastructure (Milburn, Reference Milburn2004; World Bank, 2006). In the past, the procurement of publicly used healthcare facilities and related services at the local level was reserved for Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) before they were phased out in 2012. In their time, PCTs represented the lowest level of healthcare authorities in the hierarchy of Department of Health (DoH) organization in the United Kingdom. They were encouraged to work in consultation or partnership with their stakeholders, with the intention that it would facilitate shared responsibilities with their private counterparts without impinging on service equity in performing their public mandate [Institute of Public Policy Research (IPPR), 2002]. According to the World Bank (2006), prioritizing PPP approaches would also facilitate them in mitigating shortage of capital desperately needed for investment in new primary healthcare surgeries and provision of essential non-clinical services. PPPs within the National Health Service (NHS) are underpinned by assumptions concerning improvements in service delivery. It is believed that the private participants are better skilled and sufficiently resourced to perform their allocated roles than their PCT counterparts (Milburn, Reference Milburn2004; Perrot, Reference Perrot2006).

With reference to the NHS in England, for example, a major criticism of stagnation in GP surgeries development was that the local PCTs experienced frustration by government bureaucracy [Department of Health and Partnerships for Health (DH/PfH), 2003]. They were also restricted by shortage of capital needed to invest in new GP surgeries required within their communities (Milburn, Reference Milburn2004). These factors influenced the policymakers to consider Local Improvement Finance Trust (LIFT) schemes as a PPP model to increase the stock as well as improve condition of publicly used GP surgeries. The assumptions in implementing LIFT schemes were related to the private participants facilitating the critical procurement activities traditionally led by locally based PCTs (DH/PfH, 2003). Some of the benefits arising from the underlying assumptions would include the PCTs mobilizing private sector capital resources more effectively; meeting public sector budgets; and delivering GP surgeries on time when they were needed (National Audit Office, 2005). These health benefits are achieved because private participants would avert government bureaucracy that reduced PCT staff efficiency in performing their procurement role (Sussex, 2003).

There is generally no consensus about assumptions in activities of private participants in healthcare PPPs being realistic enough to help public sector departments in either improving performance or securing health benefits. Private participants’ activities in healthcare PPPs implemented in the United Kingdom have been criticized for prioritizing processes that risk reduced efficiency and missed anticipated health benefits (Pollock and Price, Reference Pollock and Price2006). This could be construed as the assumptions held about private participants’ activities in PPPs being unrealistic in facilitating to secure health benefits associated with increased diversity and competition (Aldred, Reference Aldred2008; Fitzsimmons et al., Reference Fitzsimmons, Brown and Beck2009). The major barrier to achieving these benefits could be private participants being more inclined to respect their traditional business practices than what the policymakers may have perceived as important in making their activities in a PPP effective (Hunter et al., 2011). An analysis of assumptions in private participant activities in healthcare PPPs is therefore important. It is helpful in our understanding of role of the factors involved in supporting progress toward achieving purpose and public objectives in applying them to health (Taylor and Craig, Reference Taylor and Craig2002). In particular, the LIFT model of PPPs used in the English NHS is awash with assumptions for guiding private participant activities. It provides an opportunity to derive empirical evidence about the role of assumptions in influencing private participant activities.

Methods

Study design

This analysis is based on an original case–study designed around a qualitative research methodology. Qualitative study designs are considered helpful in developing insights into factors that influence outcomes of phenomena in relation to how the policymakers may have expected them to facilitate progress toward their primary objectives (Mack et al., Reference Mack, Woodsong, MacQueen, Guest and Namey2005). Thus, phenomena outcomes may to an extent indicate their participants’ understanding or interpretation of assumptions held about their activities (Pawson, Reference Pawson2006). Where phenomena activities are carried out under turbulent conditions like those most PPPs for healthcare, qualitative research designs are a particularly appropriate methodology. In this case–study for example, the study design helped us in using evidence that was based on practical experiences (Mack et al., Reference Mack, Woodsong, MacQueen, Guest and Namey2005) to make conclusions about key assumptions in LIFT. It facilitated us in judging on whether assumptions held about the activities of private sector components in LIFT were realistic or influenced them in adopting behavior the deviate from government intention (Marchal et al., Reference Marchal, Dedzo and Kegels2010).

Data sources

The original case–study collected a wide range of information on how LIFT partnerships were executed in two PCTs in London. Interviews and documentary analysis were the main methods for data collection. A total of 25 informants were interviewed comprising senior managers at the PCTs (n=13), premises administrators (n=5), and private sector healthcare provider representatives (n=7) directly involved in LIFT implementation activities. The objective was to gather their experiences and reflections on how assumptions in their allocated roles and activities influenced progress toward government objectives for LIFT.

The senior managers and LIFT premises administrators were directly employed of the PCTs and therefore represented the public sector views. The private sector representatives comprised independent GPs (n=5) operating at surgeries developed through LIFT; and executive staff (n=2) managing the only LIFT company with a portfolio of surgeries across the concerned PCTs. In addition, documents obtained from mainly governmental agencies were reviewed to identify and understand the guidance the policymakers considered helpful in participant execution of LIFT.

Data extraction and analysis

The data extraction and analysis processes prioritized participant activities that would either confirm or refute the factors and assumptions in private participant activities which from the policymakers’ perspective, facilitated participants in achieving anticipated health benefits in LIFT. We prioritized private participants activities over those of the PCT staff because they were the ones allocated leadership roles in executing LIFT. The PCTs retained the role to provide care and assumptions in those activities are not part of the partnership’s remit even if it involves contracting independent GPs to operate from LIFT-owned surgeries.

Our approach to data extraction involved first determining what the policymakers expected the private participants to contribute (purpose) in LIFT if they were to be helpful to the PCTs in achieving their objectives in primary healthcare. We then identified the factors or assumptions that they believed would facilitate participants in meeting their purposes. Informant interpretations of what the policymakers assumed would facilitate them and the factors under which they carried out their activities were identified from transcripts of the interviews. Despite differing perceptions about the centrality or marginality of the role of some factors to achieving intended purposes (McGrath and MacMillan, Reference McGrath and MacMillan2009), informant interpretations significantly alerted us to what restricted their efforts in helping the PCTs to make LIFT a more effective model of delivering improved GP surgeries. In Figure 1, we describe the flowchart that we found helpful in passing judgment about which assumptions in LIFT participants’ activities to prioritize for analysis.

Figure 1 Flowchart for judging assumptions for focused analysis

The logic in our choice of assumptions and factors to analyze was that where the policymakers’ expectations certainly increased or discouraged participants’ support of LIFT (eg, that all PCTs will have interest to invest in improved primary care facilities, or that investors will continue to support LIFT activities even under conditions of making losses on their capital) the outcomes were obvious and the assumptions or factors respectively realistic and unrealistic. Analyzing them would add little knowledge on our understanding about suitability of some of the PPPs applied to health. Hence choosing to focus the analysis on assumptions with the likelihood of being realistic based of informant reflections on what makes them retain their involvement and commitment to activities helpful for the PCTs in achieving anticipated health benefits. Sykes and Dunham (1995) stress it as a way of isolating the evidence that can add to knowledge by explaining to better understand suitability of some the healthcare PPPs in improving service delivery. We avoided missing important assumptions in the coding by constantly reconciling our own differences in interpretations of those vague or inexplicit assumptions in the reviewed documents and interview transcripts. The data was analyzed using NVivo software which facilitated management of the documents and coding informant reflections on assumptions in their activities and their responses to the influence of LIFT’s external factors.

Results

Beneficiaries of LIFT activities

This analysis revealed that PCTs and clinicians that they contracted to operate from the newly developed premises were the intended primary beneficiaries of LIFT. The groups that helped them in realizing the benefits were identified as private for-profit participants comprising investors and a variety of service contractors. They were hired to carry out critical activities that would facilitate the PCTs and clinical service providers in improving the procurement and maintenance of surgeries. These activities are central to PCTs objectives of increasing patient experiences with getting improved primary healthcare.

The PCTs and clinicians’ success in achieving their objectives was mainly determined by the private participants with leadership roles in LIFT’s critical activities actively showing that in their performance. The clinicians operating from LIFT premises have profit motive but we could not analyze the assumptions in their activities because how they provide care is not part of LIFT. LIFT’s remit was strictly limited to development and maintenance of the premises. In addition, their status was partly changed to PCT agents upon being contracted to provide care to the public.

Assumptions in private investors and service contractor activities

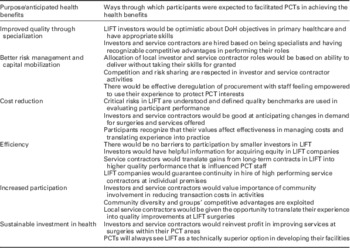

The findings revealed that LIFT is effective provided assumptions in private participants’ activities are conducive for the PCTs to achieve their objectives in preferring it over their own leadership in procurement activities. The anticipated health benefits and ways through which private participants were expected to help in achieving them are outlined in Table 1. They were either explicitly or tacitly stated in LIFT guidance and transcripts of interviews with the informants. We identified a range of assumptions that, from the policymakers’ perspectives, would facilitate participant contribution toward the health benefits. They involved six outcome categories concerning: (i) improvements in quality; (ii) better management of risks; (iii) cost reductions; (iv) efficiency; (v) increasing community involvement; and (vi) sustainable investment in health.

Table 1 Assumptions for private investor and service contractor activities in LIFTs

PCT=Primary Care Trust; LIFT=Local Improvement Finance Trust; DoH=Department of Health.

Quality improvements

Part of LIFT’s intentions was for the private participants to facilitate their PCTs in accessing private sector resourcefulness to improve procurement of surgeries. Health benefits to the PCTs centered on having surgeries of higher quality including improved standards in their maintenance. They would further benefit by having improved primary healthcare that offer patient conveniences through successful integration of public and private provider activities.

Two critical assumptions in activities for achieving these benefits were identified. First; the policymakers believed that the private participants would have the appropriate skills and optimism in interpreting their PCTs’ objectives in primary care. The informants challenged this assumption, arguing that ‘the private participants lacked familiarity with the health sector’ and this ‘…disconnected them with our priorities for quality in primary care.’ Second; it was assumed that participation was based on the providers being specialists with recognizable competitive advantages in doing their roles. This assumption was found to be realistic in meeting their quality targets because the informants considered some of the service contractors as ‘better knowledgeable about quality issues in infrastructure and their maintenance…because that was their everyday business.’

Risks management

Another purpose for LIFT was found to concern government desire to transfer risks in sourcing capital needed in procurement and maintenance of publicly used GP surgeries. It influenced their decisions to pass leadership in important procurement activities to private investors through LIFT companies. This was done mainly on the assumption that the risks would be allocated based on recipient ability to deliver without taking their skills for granted. Related assumptions were that the investors would respect competition in mobilizing capital for LIFT, and health benefits were to be optimized by the PCTs effectively deregulating their procurement activities.

We found that these assumptions were significantly contested. The majority of informants felt that the private participants did not meaningfully benefit their PCTs because perceived economic and financial benefits influenced them more than desire to deploy their skills and expertise in mobilizing capital for LIFT. A major criticism concerned their ‘overdependence on expensive finance borrowed from private banks.’ Besides risking the PCTs missing some benefits, it reduced potential savings to reinvest in delivering more healthcare facilities. Although the PCT staff deregulated procurement activities, they felt that the private participants failed to match this by empowering them to influence private borrowing for new projects. These findings suggest that contrary to assumptions, private skills and expertise were not meaningfully used in developing PCT staff ability and effectiveness to handle important risks in procurement.

Reduced costs in procurement

In theory, LIFT was recommended for helping the PCTs in spreading risks in procurement activities. The PCTs committed themselves to opening investment opportunities for private providers so that they help to reduce costs associated with public delivery and management of local surgeries. The purpose was achieved under assumptions that were premised on the private participants (i) understanding the critical risks in procurement activities; (ii) having clear quality benchmarks to facilitate evaluation of their performance; and (iii) anticipating changes in demand for surgeries and tenants’ preferred ways of providing care. As to whether these assumptions were realistic for LIFT activities was largely influenced by the values and experience that the private participants introduced in managing costs in procurement.

The assumptions were considered as not realistic in helping the PCTs in reducing costs in procurement activities. Among other problems cited by PCT managers, there were concerns that the private participants failed in appropriately interpreting the critical cost factors in LIFT; and understanding the quality benchmarks set by their PCTs. Economic imperatives also drove them to ‘unilaterally assess affordability of buildings by the PCTs and avoid using high quality inputs that result in increased rent or risk making LIFT unaffordable.’ Delivering buildings of reduced quality was blamed for increased maintenance costs. It also caused time inconveniences when tenants frequently requested modifications to their surgeries to suit how they wanted to respond to patient demands for getting care.

Efficiency in procurement activities

At least from the policymakers’ perspective, the important health benefits in introducing LIFT concerned increasing efficiency in procurement of GP surgeries necessary in order to make primary healthcare more functional. LIFT was intended to deregulate procurement through promoting specialization which would in turn encourage different investors to take financial interests in participating in developing surgeries within their PCTs. The assumption in activities to achieve these benefits was that helpful information would be provided to remove factors that prevented small investors from acquiring equity in LIFT local companies. Yet the evidence from this case–study shows that associated efficiency benefits are missed due to ‘large corporations imposing barriers to small and cheaper investors acquiring equity in LIFT companies.’

Such barriers to investment further negated a key assumption that private participants would help by producing benefits associated with competition; especially when the corporations used unaffordable sources of finance. It neither increased PCT efficiency in their procurement activities nor helped to reduce rent as done by smaller investors. Monopoly role in LIFT also risked making large corporations complacent and inefficient in their activities. The LIFT company in this case–study was not surprisingly perceived as lacking the motivation to innovate in developing better surgeries because it was the only developer across a number of PCT areas.

Participation in local procurement activities

An implied assumption central to LIFT activities relates to giving communities a voice in influencing healthcare activities in their PCT areas. The policymakers’ belief that LIFT would help in developing community capacities for delivering surgeries that reflected their priorities in getting healthcare influenced them to recommend the participation of diverse groups including non-clinical providers in delivering services considered critical to its success. But the majority of informants in this case–study were not optimistic that community resourcefulness was being effectively tapped or invested to involve the groups that are familiar with local healthcare problems. Currently, those engaged to participate were the for-profit providers at the expense of voluntary, mutual aid, donors or self-help groups with a foothold in health.

The perception of staff at the PCTs was that majority of the participating service contractors were insufficiently acquainted with critical risk components in what LIFT was expected to improve. This is because of either (i) coming from outside of the PCT areas; (ii) being new in managing healthcare estate; or (iii) experiencing difficulties in subordinating their business principles to public objectives for LIFT. These factors reduced effectiveness of their activities translating into health benefits and enhancing community participation.

Sustainable investment

At the national level, the ultimate purpose of adopting the LIFT model of procurement was in order to achieve sustainable investment in primary healthcare facilities neglected in the past (DoH, 2001). The policymakers assumed that the activities for achieving this would involve: (i) the PCTs continuously considering LIFT as a better alternative to them in leading the development of GP surgeries; while (ii) income guarantees would spur private providers to offer support by participating in LIFT activities. These assumptions would be considered realistic provided the participants get incentives to align their financial practices to PCT objectives in order to reduce transaction costs in LIFT.

This analysis revealed uncertainty about the participants’ ability to deliver sustainable investment. There was evidence of them missing anticipated savings for reinvestment in increasing the stock of primary healthcare facilities. As a result, PCT staff lost ‘enthusiasm about retaining LIFT as it was financially unaffordable.’ Preferring established corporations over cheaper contractors to provide basic maintenance services like cleaning at the surgeries not only inefficient but also undermined sustainable investment.

Discussion

This study revealed that healthcare PPPs are driven by desire to increase public sector efficiency through engaging diverse non-governmental including the for-profit providers in service delivery (Ham, Reference Ham2009). Their implementation is the recognition that engaging private providers may be the best option in increasing service quality; accessing private sector resourcefulness; and spreading important risks in healthcare activities. These inputs are important and necessary if a health system is to achieve sustainable investment (DH, 2001; DH/PfH, 2003).

The evidence in this case–study showed that the ways through which private participants chose to carry out their activities significantly influenced PPPs’ ability to achieve their purposes. It is apparent that participant performance is a good indicator of how they may have interpreted the ‘assumptions’ held about their activities. While the policymakers may have considered the assumptions as helpful, it is obvious that participants assess if they are realistic in their activities to achieve a PPP’s objectives (Pawson, Reference Pawson2006; Klein, Reference Klein2007). Hence importance in explaining to better understand why some PPPs may fail when applied to health (Renda and Schrefler, Reference Renda and Schrefler2006). The knowledge may be helpful in suggesting implementation contexts that are more likely to facilitate participant effectiveness in achieving PPP objectives. This study provides clear evidence about the role of assumptions in determining behavior of private participants in LIFT. The behavior define contextual factors that may help to uphold perceived good practices and anticipated health benefits in other PPPs’ activities (Pawson, Reference Pawson2006). It confirms that PPPs’ ability to achieve their objectives is influenced by participants’ interpretation of assumptions in their activities, and degree of allegiance to their principles for service delivery Pollit and Bouckaert (Reference Pollit and Bouckaert2000).

Together with informant indications that health benefits in LIFT activities varied along the challenges in its governance, these findings influence us to argue that participant acquaintance to routines and good practices in health service delivery are important determinants of PPPs’ effectiveness. After all there is evidence that challenges always exist in staff monitoring to ensure that the private providers understand in order to correctly interpret what is assumed about their activities in PPPs (Perrot, Reference Perrot2006). For example, they may misinterpret their leadership in PPP activities as a sign of being superior than their public sector counterparts in influencing activities critical to improving public service delivery. Besides nourishing counter suspicion between the supposed partners, it risks creating non-conducive environments that render key assumptions considered helpful for producing anticipated health benefits unrealistic (Aldred, Reference Aldred2008; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Toms, Mannion, Brown, Fitzsimmons, Lunt and Green2009).

The evidence the importance of not taking for granted that all private PPP participants are ready to sacrifice their values to promote public objectives. At least in the United Kingdom, inertia prevents most participants from adapting their business principles to suit the unique circumstances within health (Sussex, 2003; Pollock and Price, Reference Pollock and Price2006). Consequently, some of the assumptions considered critical for their activities to help in achieving health benefits are made impractical. LIFT provided ample evidence of participating corporations having ‘a good position to influence the decisions of government agencies’ (Ham, Reference Ham2009: 149) to prevent smaller provider from competing for lucrative contracts.

We highlight the importance of community participation theory because its assumptions dominate the guidance for implementing LIFT. The policymakers implicitly considered all private providers including for-profit corporations as part of community groups to be made accountable for LIFT outcomes provided they actively involved themselves in leading its implementation (Baggot, Reference Baggot2011). But in light of inclination to prioritize their profit motive, there may be good reasons in challenging the logic of treating corporations as part of community groups suitable for leadership role in PPPs. It has been suggested that giving local staff increased discretion in influencing LIFT activities may facilitate ordinary service-user involvement needed in making the PCTs more responsive to healthcare needs of communities (King’s Fund, 2008).

Some of the health benefits in LIFT were missed due to PCT staff experiencing problems in monitoring private participants’ performance. Yet this may be important in order to make them accountable for consequences of not complying with perceived good practices; and agreed upon standards. Giving PCT staff increases discretion is also logical because without that, private providers may lack incentive to respect the supervisory role of people who are not their direct employers. Hence cautioning against taking for granted that their involvement in PPPs would optimize health benefits unless they show evidence for being comparatively better performers.

Conclusion

This analysis has shown that PPP characteristics alone may not adequately explain why and how they may fail to deliver benefits when applied to health. Indeed the private participants bring in important new skills and expertise but how they interpret the assumptions held for their activities as realistic and practical in facilitating their performance is much more helpful in achieving anticipated health benefits. Changes in contexts of PPP activities; and participant allegiances to their principles for service delivery relative to purpose of a given PPP have the potential to influence how the assumptions are interpreted. LIFT shows evidence that some assumptions are critical while others are of marginal importance to the participant activities for increasing health benefits. However, linking between the critical assumptions and health benefits may be distorted by frequent changes in economic and political factors (Perrot, Reference Perrot2006).

Ethical considerations

This case–study was supported by the boards of the two PCTs and their LIFT company. Ethical approval was granted by the UEL Research Ethics Committee. All participants were assured anonymity and confidentiality of their contributions.

Limitations

A limitation of this paper is that it is based on one case–study. However, the combined experiences of the two PCTs and one PPP company as part of the pioneers of LIFT gives us the confidence to generalize the potential consequences of engaging the for-profit sector in performing public health functions. Our reconciliation of the informants’ experiences and assumptions in their activities revealed that how the private participants interpreted and translated some key assumptions into practice affected their ability to make healthcare PPPs effective.

Acknowledgments

The paper draws on a broader study hosted by the Institute of Health and Human Development, UEL. The authors thank all the study participants for their contributions.