Introduction

In most primary care practices in the Netherlands, at least 30% of visits to the general practitioner (GP) involve patients with psychosocial problems. The prevalence of patients exhibiting psychosocial problems in primary care practices is estimated to be as high as up to 50% of all consultations (Rosenberg et al., Reference Brandling and House2002; Walters et al., 2008; GGDAtlas Databank, Reference Van der Zee, Priesterbach, Van der Dussen, Kap, Schepers, Visser-Meily and Post2012). People with psychosocial problems consult primary care practices more often than people without psychosocial problems do (Cardol et al., Reference Friedli, Jackson, Abernethy and Stansfield2004; Smits et al., Reference Friedli and Watson2009). Psychosocial problems are often related to life events, such as relationship problems, loss of work or a sick partner, and can manifest as physical symptoms, stress, depression and anxiety. For most of these problems, neither medical nor psychological care is necessary. Moreover, there is some doubt about the effectiveness of medication for mild psychosocial problems (Thio and Van Balkom, Reference Grant, Goodenough, Harvey and Hine2009). Primary care physicians do not have the ability or skills to modify these risk factors. They often treat these patients with sleep medication or tranquilisers, which does not address the cause of the problems (based on data from electronic patient records of primary care centre De Roerdomp, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands, 2012–2015). For most people with psychosocial problems, participating in a social activity seems to increase the level of well-being (Friedli et al., Reference Kimberlee2008). Social activity has been shown to reduce complaints, improve well-being and increase engagement in exercise/sports (Brandling and House, Reference Rosenberg, Lussier, Beaudoin and Kirmayer2009; Van der Zee et al., Reference Langford, Baeck and Hampson2010; Kimberlee, Reference Thio and Van Balkom2013; Langford et al., Reference Smits, Brouwer and van Weert2013). Despite the aforementioned positive effects, it should also be mentioned that engaging in healthy community activities has not been shown to reduce costs (Blickem et al., 2013).

‘Welzijn op Recept’ is a programme that allows primary care providers to refer patients with psychosocial problems to a local social well-being organisation. The programme was developed through cooperation between primary care centre De Roerdomp, well-being organisation MOvactor and the Trimbos Institute (the Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction) in 2012. Welzijn op Recept seeks to offer support in maintaining and improving the health and well-being of people with psychosocial problems that do not require medical or psychological treatment. The objective is to enhance the participants’ quality of life by helping them re-engage in activities and create new social contacts (Walburg, Reference Walburg2008). In 2013, a pilot study was conducted in which 59 patients were referred to the project. Of these referrals, 75% were women and the average age was 59 years. The most common reasons for referral were loneliness, anxiety and depression. A third had mobility problems and half of the patients experienced severe pain. The referred patients visited their general practitioner more frequently than the national average. After the pilot project, the programme was first extended to other primary care centres in the town of Nieuwegein and, in 2015, to other towns in the Netherlands.

The target group for Welzijn op Recept comprises patients who frequently visit their GP or other primary care provider about psychosocial problems for which no medical cause can be found (trouble sleeping, worrying a lot, feeling depressed, etc.). Many of these patients have recently gone through one or more life events (a move, job loss, sickness, death of a partner, etc.). These patients exhibit the following symptoms: loneliness, a recent life event, chronic illnesses, minor psychosocial problems or a stable psychiatric condition.

Since 2013, the number of referrals per year has stayed nearly the same, around 120. At the end of 2014, we performed a mixed-methods study to assess the impact of the Welzijn op Recept programme on healthcare costs, GP attendance rates, health outcomes and patient well-being. This paper describes the results from the qualitative portion of our study. In this report, we investigate which patients were referred to the social well-being organisation and the nature of their psychosocial problems. Further, we evaluate the process after the programme is prescribed and we seek to understand patients’ experiences and perceived outcomes from participating in the programme. To do so, we interviewed 10 participants.

The Welzijn op Recept programme

In Nieuwegein, GPs, physical therapists, assistant practitioners and psychologists from four primary care centres are able to refer patients with psychosocial problems to the social well-being organisation MOvactor. These patients first undergo a medical examination at the primary care practice to determine whether their problems have a somatic cause. Once medical causes have been ruled out, the patient is informed that his/her symptoms and problems do not have a physical cause and that the best intervention is referral to the community well-being organisation. The primary care worker issues a social prescription to the patient, provides a pamphlet with general information about Welzijn op Recept, and asks for his/her permission to have a well-being coach contact the patient. An assistant practitioner then registers the patient with the well-being coach by telephone or email. Referrers are asked to not only properly register their diagnosis in the GP information system upon referral, but also to include the code WOR (Welzijn op Recept).

The well-being coach then contacts the patient and schedules an appointment for a one-on-one intake session lasting 1 h. The intake session takes place either at the participant’s house or in the community well-being centre. During the intake session, a well-being coach uses a strengths-based approach to evaluate the participant’s life in a holistic manner. The patient’s sources of positive energy and strength are systematically identified. Additionally, possible barriers to thriving are also explored so that they can be addressed throughout the process. The well-being coach uses a step-by-step approach that focusses on what the participant enjoys doing. For example, the coach may ask ‘What were you good at previously?’ The coach aims to reinforce the patient’s self-efficacy and self-reliance through social activation. Social activation is meant to re-connect people to their community and other community members through activities like being a volunteer in the community centre or participating in a social community activity, such as cooking classes, repair gatherings, bingo, etc.

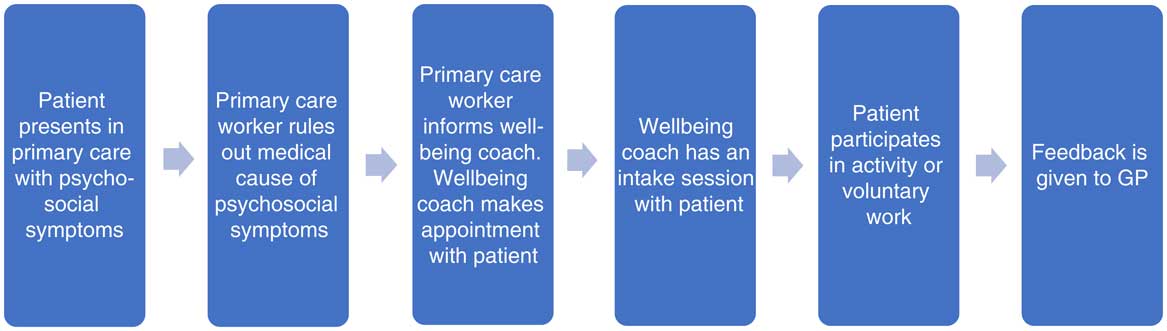

At the conclusion of the intake session, the patients – now called ‘participants’ (of the Welzijn op Recept programme) – choose, with support and coaching from the well-being coach, the activity they find most appealing or that they will most likely benefit from. Participants are encouraged to pursue activities that promote positive social–emotional health (Grant et al., Reference Van der Zee, Priesterbach, Van der Dussen, Kap, Schepers, Visser-Meily and Post2000), namely, positive thinking, living with meaning and purpose, consciously living and enjoying life, interaction with others, living a healthy lifestyle and sharing happiness. The well-being coach then searches for local offerings provided by the well-being organisation and those of other providers in the volunteer and community sector. Next, the participant is registered with the coordinator of the desired activity. The Welzijn op Recept pathway is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Welzijn op Recept pathway

A monitoring and evaluation system was set up to prospectively evaluate the programme. Agreements between the primary care provider and community well-being organisation were made regarding referral procedures and there was regular mutual feedback. Additionally, the need for joint ownership was recognised.

One of the challenges that continue to face the project is the cultural differences between care and well-being. For example, the primary care organisation focusses on what the ‘patients’ cannot do and their complaints, while the community well-being organisation focusses on what ‘participants’ like to do and can do. Furthermore, the privacy aspect in primary care contrasts strongly with the need to connect people in the community well-being organisation.

Methods

The research questions of the qualitative study were the following: ‘What happens in the social prescription process?’ and ‘What changes do people experience regarding social participation?’ For the purpose of this study, social participation was defined as a person’s participation in social life, and the study examined the extent to which participation had increased or decreased. The social prescription process comprised the following components: the referral by the care provider, the appointment with the well-being coach, the intake session with the well-being coach, the selection of an activity and possible follow-up appointments with the well-being coach. The interview questions were aimed at exploring the experiences of the patients/participants in this process.

A team comprising a policy advisor, two well-being coaches and two researchers developed a list of relevant topics to create a topic guide based on their own experiences and the literature. The topic guide was first pre-tested on two people and then adjusted. We used an ongoing, iterative process of analysis to refine the topic guide while interviews were conducted. Two researchers, independently of one another, analysed the first three interviews, after which new topics were included in the topic guide (financial situation, social network) (see Appendix 1). The analysis process was performed as follows: the first interview was analysed, after this, a list of themes and sub-themes was developed from which the following two interviews were analysed and the list was adjusted accordingly. This list was used to code the next two interviews, and so on (see Appendix 2).

Participants were selected using a purposeful sampling method: three well-being coaches were asked to approach persons with social issues as well as those with psychological or more serious issues. They also made sure to include at least one person for whom the referral had had no result. Next, 10 in-depth interviews were conducted, which took between 1.5 and 2 h each. Five female and five male participants were interviewed. The participants’ average age was 69 years (range 48–91). Six were referred for social issues only, while four were referred for psychological issues.

Interviews were conducted in the participants’ homes by the principal researcher, who holds a PhD in qualitative research, together with a social scientist as co-researcher. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, encoded and thematically analysed. The software program QDA Miner 4 was used.

Results

We elicited five overall themes of the social prescription process: life events, referral and intake process, personal strength and responsibility, self-reliance and social activation/participation. These five themes are described in greater detail below. The theme headings below are followed by quotations from the participants.

Life events: ‘I am not doing so well, of course’

The participants had been dealing with one or more life events (eg, the loss of a job, sickness of themselves or a partner, death of a close family member) in the two years preceding their referral, which they either had not or had not fully come to terms with. Participants stated that they were in a deep hole and were highly emotional or stressed. At some point, they felt a need to change the situation they were in. They no longer wanted to spend so much time sitting around the house; they wanted to feel less depressed and anxious and to have something to occupy themselves with or somebody to talk to. One participant talked about the problems he had experienced and how the programme could help him:

What were your expectations of the referral? To meet people again. You know, my house is for sale and I am divorced; luckily my son lives with me. That’s his choice. That was a difficult time. And I have no work. I am looking for something to do during the daytime. In the end you end up in a black hole … It is difficult to find a job; I am 51 years old! You know, after a while with all that worrying and nagging, you withdraw yourself. Looking at my son, I have to find myself again. Maybe the volunteer activities within this programme can be of some help.

(Interview 3)

People who were still in the first stages of coming to terms with their life event indicated that they felt a greater need for support from their GP, psychologist or well-being coach.

The referral and intake process: ‘This just might be good for me’

The interviews showed that patients have confidence in the GPs referral. After the referral, people are contacted by the well-being coach by telephone to set up an intake session. The participants mentioned that they appreciated the intake session and the bespoke service it provided. Most people indicated that they needed a ‘big stick’ and also that going somewhere alone presented a major obstacle. The following participants refer to how difficult it was to make that first step towards participation. One person went alone, while the other was accompanied:

The wellbeing coach made an appointment for me at the activity centre and had told them that I would come. But still … It is difficult … to go on your own.

(Interview 2)

Last Saturday was the first time that I attended the activity. The wellbeing coach joined me, because I would not have gone alone. Going alone to a new group of people is very difficult. At the moment, I am not as I usually am. Normally, I am the centre of a group, but now … it sounds strange, but I am not as I usually am. It was good that the wellbeing coach accompanied me.

(Interview 3)

The participants appreciated making agreements on this subject during the intake session (for instance, making appointments by telephone, having the activity coordinator wait for them at the door or going to the appointment with another person). Some participants had a follow-up session with the well-being coach after their first participation in an activity. This was experienced as a stimulus to continue with the activity. The lack of a follow-up session could be a reason to drop out, as shown in the following example (this woman did not return to the activity):

I missed the so-called ‘big stick’. It was hard for me to attend the activity the first time. I went, but people did not say much to me and that made it harder for me to go back the next time. That’s a problem for me. The wellbeing coach called me to ask how I felt, but in the meantime, my problems got worse. The wellbeing coach told me on the phone to look on the internet for other options. But going there alone is difficult. That is not funny to say. I know I can look it up and that they can make an appointment for me. They suggested asking my neighbour to accompany me to the activity, but … to ask something like that … it’s difficult. I feel like I cannot do that by myself.

(Interview 2)

Strength and responsibility: ‘Getting your life back on track and finding new social contacts’

Even though the researchers did not bring them up during the interviews, subjects such as the participant’s own strength and responsibility were frequently mentioned. The term ‘own strength’ refers to the power to find one’s own solutions to problems. The intake sessions made it clear that it was important to the participants that the activities match their own needs, interests and hobbies. They indicated that their participation in Welzijn op Recept empowered them to regain control over their lives. A man who liked swimming in the past but was experiencing depression at home spoke about how he was supported in his desire to begin swimming again:

During the intake, the wellbeing coach asked me what my hobbies were in the past. I mentioned that I loved swimming. She told me that at the swimming pool there were special hours for handicapped people. I did not know that. For an hour we discussed possibilities and options. She did this well. She made me very enthusiastic and made an appointment for me at the swimming pool. At this club, I can swim at my own pace and for as long as I want. If I want to take a break, that is possible. My health is improving.

(Interview 1)

A number of the participants exhibited a more cautious or depressive style of coping. A distinction could be made between those whose basic attitude was cautious or depressive and those for whom this attitude was a reaction to their life event. The former group expected lasting support from the project, which raised the question of whether this group is suited for Welzijn op Recept.

Self-reliance: ‘What you need is a big stick and a stimulus to continue’

As stated above, participants indicated they needed a strong incentive to go to an activity. Their self-reliance, the ability to make arrangements for continued participation in society, was limited. For them, support from others in their immediate environment – neighbours or family – but also from the referrer and the well being coach was important. The referral, the intake session and particularly the follow-up sessions were experienced as a stimulus to change, and to keep changing, their situation. The man who went swimming expressed the following:

Since I started swimming, I have the feeling that my health is improving and I feel much better. I’ve met new friends. I cannot join a walking group, but besides walking there are many other things I am able to do. That is a thing that I have learned lately. I have to keep that feeling.

(Interview 1)

Notably, a new social network was created by people who encouraged each other to keep coming and pointed out other interesting activities to each other. Financial considerations also played an important role in selecting activities.

Social activation/participation: ‘An activity that fits your wishes and abilities and who you are’

Regarding the activities, it was important that they matched with the participants’ interests, and that the participants could identify with others in the group (for instance, in terms of age and gender ratio). People around the age of 55 found it particularly difficult to find an activity with people their own age that took place during the day on a weekday, because most daytime activities are geared towards older, retired people. A man said the following regarding the age difference:

The activity I went to was okay. There was nothing wrong with that; it has more to do with my feelings. What they do is nice and pleasant, but I do not want to continue going. The people in that group are of age. I am not young, but these people are much older. It felt like I was attending a seniors club, and that did not appeal to me. It would be better if there were activities for people of my age during the day. In the evenings, my friends come home from their work.

(Interview 3)

Within Welzijn op Recept, people could also be assigned a buddy. Participants who were assigned a buddy said it is important that there be a click; one must be able to recognise oneself in the other. This could be the result of taking a mutual interest in each other, being of the same age or sharing the same hobbies or interests.

One woman mentioned that her first buddy was a woman from a different area with whom she had no connection. Later she was assigned a new buddy, who was a woman from the same town:

There has to be some connection, you know. The first buddy came originally from (another area), she talked a lot about this area and now … I do not know, all the things that happened there … When I talked about my past in this town she answered, ‘I do not know, that was before my time’. I do not want to impose myself, but I want to have something in common, to have something to talk about. Later, they found someone else. We always have a pleasant time. We do our shopping together and have some tea together. And have a social talk. She comes every Tuesday morning.

(Interview 4)

Half of the participants took up volunteer work (again). In addition to new social contacts, volunteer work also gave them the feeling of being useful to others. Resuming activities rekindled the participants’ interest in hobbies. The increase in social participation and the accompanying increase in social contacts led to a sense of satisfaction about the life they were now leading.

The impact of Welzijn op Recept

During the interviews, the participants mentioned the following ways in which they benefitted from Welzijn op Recept: gaining new experiences – again, meeting new people, exercising more and feeling good about it, having something to look forward to, regaining control, becoming more self-reliant, regaining perspective and experiencing improved health.

Health professionals noticed a clear change in the mental, physical well-being and behaviour of most of the patients who participated in Welzijn op Recept, although this change was not verified in a systematic, scientific way.

Discussion

Main findings

The main findings of the study were that most of the patients who were referred to Welzijn op Recept had experienced one or more life events (eg, loss of a job, sickness of themselves or their partner, death of a close family member) in the two years prior to referral. All of the patients had confidence in the GP’s social prescription. The participants appreciated the well-being coach’s active approach and the intake session. A follow-up session with the well-being coach was deemed necessary by the patients and lack of a follow-up session could lead to drop out. The well-being activities discussed with the participants matched their own interests, needs and hobbies, and participation empowered them to regain control over their lives. As the participants’ had limited self-reliance and ability to make social arrangements, support by the well-being coach was often necessary to go to an activity.

Regarding the activities, a link with a former interest or hobby was essential, as well as a connection with the other participants in the group in terms of age or interests. Half of all participants took up volunteer work.

The impact of Welzijn op Recept on the participants was that they mostly felt healthier, became more self-reliant, and regained perspective and control over their lives.

Interpretation

One of the research questions of this study was ‘What happens in the social prescription process?’ Patients were referred for a variety of reasons and at different phases of dealing with their life events. For example, while one person was still in a transitional phase and was trying to come to terms with the life event, another had already moved on with her life. It is of great importance to the future of the programme to determine in which phase Welzijn op Recept is most suitable for patients. The referrer must determine whether a patient is ready for new activities or needs to resolve other issues first. Should the patient first be referred to social services or a psychologist, or could such a referral be made in addition to Welzijn op Recept?

In this study, the coaching and support provided by a well-being coach played a crucial role. Brandling and House (Reference Rosenberg, Lussier, Beaudoin and Kirmayer2009) conclude that personal guidance by someone who is locally embedded and familiar with an up-to-date overview of activities in the area is of vital importance. Langford et al. (Reference Smits, Brouwer and van Weert2013) suggest that one of the challenges is determining whether the well-being coach can handle the number of referrals and the requested coaching within the limited time and means at their disposal. This study shows that participants who had follow-up sessions with the well-being coach, in addition to the intake session, experienced these sessions as pleasant and a stimulus to continue with the activity. Participants who did not have follow-up meetings experienced this as a shortcoming, and for some this was the reason they did not return to an activity. Scheduling follow-up sessions as a standard procedure could therefore improve results. Kimberlee (Reference Thio and Van Balkom2013) conclude that in this context it is crucial that the well-being coach not be bound by time and/or financial limits. In the current era of budget cuts, this poses quite a challenge.

The multi-facetted role of the well-being coach, who acted as both a conduit and a guide, was noteworthy. The coach was a conduit between the primary healthcare provider and the selected activity, and a guide towards an activity, volunteer work or a buddy. In the United Kingdom, the well-being coach (link worker) responsible for social prescriptions may work within a GP surgery and meet patients there, but increasingly, he/she is also based in the community. It is variable and depends on how the social prescription scheme has been set up. Welzijn op Recept in Nieuwegein and other places in the Netherlands has clearly proven that well-being coaches offer added value. They not only lead people to an activity, but also look at the question behind the question. They do not focus on the problems and limitations of the participants, but instead look for the participants’ strength and resilience. The study has demonstrated a number of important active ingredients for social prescribing. Well-being coaches boosted the participants’ self-confidence, strength and self-resilience. This forms part of the profession of well-being coach, and this is what sets them apart from other professionals in the social domain. We believe that this is the strength of the short intervention that is Welzijn op Recept. These professional skills of the well-being coach need further elaboration and description in a ‘well-being standard’.

The second research question of the study comprised the following sub-questions: ‘Which changes do people experience regarding social participation?’, and ‘What has it brought people in terms of social participation?’ Generally speaking, the social involvement of the participants was particularly enhanced when they engaged in recreational activities and volunteer work. However, the increase cannot be fully attributed to their referral to Welzijn op Recept. Some participants had independently found activities or volunteer work. There is, however, a difference between the older and younger target groups. There is a clear argument for increased differentiation of activities, as people tend to stop participating in an activity if they cannot identify with the group. An increase in the participants’ self-reliance and social participation led to an increased sense of satisfaction with their lives.

Within Welzijn op Recept, one should not focus too much on the end result, namely, social participation. A crucial question in this regard is, which aspect is the most important, success (social participation) or the learning process (increasing self-confidence, strength and self-reliance), the social activation? The ‘active ingredients’ are improved health, connecting with others, having positive experiences, increasing self-confidence, and regaining perspective and control over one’s life.

Limitations

Social well-being professionals are not yet familiar with the standardized approach that is the norm in the primary care sector. Additionally, questionnaires and other quantitative instruments used to measure and monitor the process and outcomes of intervention are not common in the domain of social well-being.

Due to time and financial constraints, the qualitative part of the overall study could not be expanded to more than 10 clients.

Conclusion and advice

To improve the process of Welzijn op Recept, we advise that it be standardised and professionalised. This would include the use of intake-enhancing instruments, an electronic client registration and referral system, a competency profile of the well-being coach and a greater focus on the development and use of specific working ingredients in the process of Welzijn op Recept. For example, one could make use of elements of positive psychology, which offers a future-oriented, strength-based approach to addressing psychosocial issues. For the standardisation of the process, we would advise using a value-chain approach.

Concerning future research, it would be best to conduct a randomised-controlled trial focussing on the process, the outcomes (improvement of health, well-being and participation) and the social return on investment.

Financial Support

This study was funded by ZonMw (grant number 841002003).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. This article was previously published in a smaller version in Bijblijven in 10 December 2015.

Appendix 1: Topic guide

Introduction and informed consent

Activity participant started with

Referral: (By whom, what were their problems, needs and questions at time of referral, experience)

Intake: (Was it an answer/solution to their questions/problems? experience with intake)

What is different now? Have things changed?

Social participation: Have things changed or remained the same? Satisfaction.

Evaluation Welzijn op Recept: Suggestions for change, their expectations.

Closing: Do they have questions?

Appendix 2: List of themes and sub-themes used for analysis

Gender: man, woman

Problem: disability, old age, retired, unemployed, widower/widow, house for sale, divorced, illness.

Trigger (to go to GP): life event, volunteer aid (at home).

Referral: reason, referral, appreciation

Intake: intake coach, appreciation, follow up

Activity: which activity, preference, first care at activity, appreciation activity, buddy

Welzijn op Recept: appreciation, effect, transition

Patient’s own strength: coping, possibilities in environment, talent, people in environment, publicity

Self-reliance: self-reliance, social contacts, network, support neighbours

Future: future person, future preference, future activity

Finances.