Morbidities associated with energy intake (deficiency and excess) are prevalent worldwide. By the year 2015, 2 million adults were overweight, and 462 million were underweight. Furthermore, 42 million preschool children were overweight, and 156 million were affected by nutritional stunting(1). Micronutrient deficiencies are still a public health concern. For example, the globally estimated prevalence of anaemia in children, pregnant women and women of reproductive age are 42·6, 38·2 and 29·0 %, respectively; furthermore, between 42 and 50 % of anaemia cases may be alleviated by prevention programmes(2). Thus, nutrition associated with public health problems has two concomitant factors (under- and overnutrition) that can be recognised as a double burden of malnutrition (DBM)(1). The United Nations General Assembly proclaimed the years 2016–2025 as the Decade of Nutrition. One of the aims of this UN declaration includes ‘catalyzing and facilitating alignment of on-going efforts of multiple actors from all sectors, including new and emerging actors, to foster a global movement to end all forms of malnutrition and leaving no one behind’(3).

According to a social epidemiological perspective, socioeconomic status (SES) is a combined economic and sociological measure of a person’s work experience and of an individual’s or family’s economic and social position in relation to others. This definition examines household income, earners’ educational level and occupation, as well as combined incomes, whereas for an individual’s SES, only their own attributes are assessed. However, SES is more commonly used to depict an economic difference in society as a whole(4,Reference Basto-Abreu, Barrientos-Gutiérrez and Zepeda-Tello5) . In this case, it is important to elucidate how low SES and education have been shown to be strong predictors of a range of nutritional problems in vulnerable age groups (e.g. children and non-pregnant adolescent and adult women)(Reference Marmot6,Reference Krieger7) .

In this way, recent studies showed that low SES was associated with a reduction in life expectancy and premature mortality, mainly from diet-related to non-communicable diseases (e.g. obesity, diabetes and hypertension)(Reference Zhernakova, Zheleznova and Chazova8–Reference Djalalinia, Peykari and Qorbani10). These studies suggested that individual factors (education, occupation and income) were affected by external factors that generate stratifications or status in both individual and population health. This issue radically affects the formulation of economic, social and health policies because this approach should come from the determinants of health rather than from purely economic interventions(Reference Berkman and Kawachi11). The study of the association between SES and malnutrition is especially relevant for Latin America, where economic growth, rapid urbanisation and an increase in inequality with subsequent transformation of the food system have been observed(Reference Lloyd-Sherlock12,Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng13) . These conditions represent challenges to improving nutrition in the region(Reference Uauy and Monteiro14,15) .

In Colombia, positive economic growth has been occurring and is indicated by a positive gross domestic product (GDP) index. However, GDP has varied from 2·0 % in the fourth quarter of 2016 to just 1·1 % in the first quarter of 2017(16). In addition, economic inequity may be high, as the national GINI index of 2016 was 0·517, with 0·495 in urban zones and 0·458 in rural zones(17). Colombia is experiencing a nutritional transition as well(Reference Marmot6), where both facets of the DBM are evident. Nutritional stunting affects 13·2 % (95 % CI: 12·5, 13·9) of preschool children, while 20·2 % (95 % CI: 19·4, 21·0) are at risk of being overweight, and 10·6 % (95 % CI: 9·3, 12·0) suffer from iron deficiencies(18). Preliminary research suggests that a low to high prevalence of overweight and obesity (3·4–51·2 %) co-exist with a moderate to high prevalence of anaemia (8·1–27·5 %) and stunting (13·2 %). However, the relationship between socioeconomic determinants (i.e. SES, educational level and ethnicity) and malnutrition is limited to a single study conducted over a decade ago, and education and ethnicity have not been evaluated in combination with malnutrition in Colombia(Reference Sarmiento and Parra19,Reference Garcia, Sarmiento and Forde20) . Because of the historic civil conflict has promoted segregation and internal displacement of indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities, it is important to explore the association between these variables and nutritional problems; independent of other SES approximations(21,Reference Barrero and Barrero22) . Thus, the objective of the current study was to examine the association of all forms of malnutrition and SES, educational level and ethnicity in children <5 years and non-pregnant women in Colombia.

Methods

Data source and sampling

Our analysis used cross-sectional representative data from the 2010 Colombian Demographic and Health Survey ((Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud (ENDS)) and the National Nutritional Survey (Encuesta Nacional de la Situación Nutricional en Colombia (ENSIN)), acronyms are in Spanish, were collected at the same time (simultaneously) to the same persons(18,23) . These surveys applied a multistage, population-based sampling design stratified by clusters (house-hold segments) that included 50 670 households to obtain national and sub-regional representativeness (sixteen sub-regions), with oversampling of rural areas and low-wealth groups that covered 99 % of the population. The response rate for anthropometric measurements was 85 % of the sample population between 0 and 64 years(18). The sample for the current analysis comprised 19 734 children <5 years, 16 831 women between 11 and 19 years and 44 051 women between 20 and 49 years. The Profamilia Institutional Review Board on Research involving Human Subjects and the Colombian National Institutes of Health granted local ethical approval for the current study.

Evaluation of malnutrition

During ENDS/ENSIN(18,23) , weight and height were measured with standardised equipment. Weight was measured to the nearest 0·1 kg using a digital weighing scale (SECA model 770), and participants were instructed to wear light clothing and remove their shoes. Height was measured to the nearest 0·1 cm with a portable stadiometer (Shorr Productions), and length was measured in children 2 years or younger in a prone position following established protocols(24,Reference de Onis and Habicht25) . Hb was measured by the Hemocue method (HemoCue AB) and adjusted according to altitude, and tobacco use was measured as recommended by the International Nutritional Anaemia Consultative Group(26).

The criteria for malnutrition were as follows: overweight: BMI-for-age z score >2 and ≤3 for children <5 years; BMI-for-age z score >1 and ≤2 for women 11–19 years and BMI ≥25 and <30 for women 20–49 years. Obesity: BMI-for-age z score >3 for children <5 years; BMI-for-age z score >2 for women 11–19 years and BMI ≥30 for women 20–49 years. Excess weight (overweight/obesity) in children <5 years: BMI for age z-score >2; non-pregnant adolescent women 11–19 years: BMI for age z-score >1; non-pregnant adult women 20–49 years: BMI ≥25 kg/m2. Wasting/underweight in preschools: weight for age z-score <−2; non-pregnant adolescents 11–19 years: BMI for age z-score <−2: non-pregnant adult women 20–49; BMI <18·5 kg/m2. Stunting/short stature in preschools: height for age z-score <−2; non-pregnant adolescents 11–19 years height for age z-score <−2; non-pregnant adults 20–49: height <1·49 m(27,28) . Among children 6–59 months, anaemia was defined as Hg <110 g/l and in non-pregnant women Hg <120 g/l(26).

Sociodemographic characteristics and socioeconomic status

The sociodemographic characteristics collected included sex, age category (children <5 years, non-pregnant adolescent women 11–19 years and non-pregnant adult women 20–49 years), ethnicity (indigenous, Black/Mulatto/Afro-Colombian and other ethnicities identified by self-reporting) and level of education 0–6 years (elementary or basic school), 7–12 years (secondary school) and >12 years (high school). SES was assessed by using the Sistema de Identificación de Potenciales Beneficiarios de Programas Sociales (SISBEN; the Spanish acronym for Identification System for Potential Beneficiaries of Social Programs). The SISBEN III is an indicator of SES designed by the Colombian Government to identify families who might benefit from social programs, it is built from the dimensions of health, education, housing and individual vulnerability(29). The information was collected by questionnaire, which was sent to adult family members and households. The collected information was classified into one of six levels. The population who fell in the lower levels of the SISBEN index were considered vulnerable and prioritised for the state’s economic and social programmes.

Statistical analysis

The sociodemographic characteristics were described as a percentage and prevalence (95 % CIs) by age groups. In supplementary analysis, SES was divided into three categories: low SES (SISBEN index 1), medium SES (SISBEN index 2–3) and high SES (SISBEN index 4–6). To analyse household characteristics by SES, a linear trend test was used. We compared the prevalence of over- and undernutrition indicators by SES, educational level and race/ethnicity using linear adjusted combinations of the estimates (lincom function on Stata) (unadjusted estimates were described as supplementary material). For all analyses, a P < 0·05 was considered statistically significant. Individual sample weights were applied to all analyses using the survey prefix command (SVY) to account for the design of the study. The Stata 15 program (StataCorp) was used to conduct the analyses.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the population by age groups in Colombia

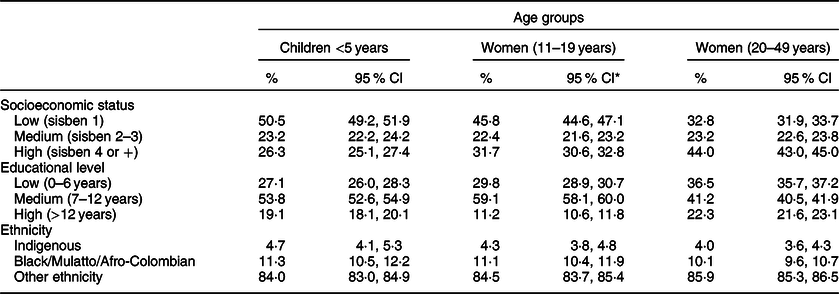

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the population by age groups. In children <5 years, non-pregnant adolescent women (11–19 years) and non-pregnant adult women (20–49 years), most of the individuals lived in low SES, presented medium education level and were classified in other ethnicity categories than indigenous and Afro-Colombian. Supplementary Table 1 shows the percentage of the indigenous population in the low SES category was 2·7 times higher than that in the high SES category. Similarly, the percentage of Blacks/Mulatos/Afro-Colombian in the low SES category was 2·1 times higher than that in the highest SES category. Adult, non-pregnant women in the low SES category exhibited a prevalence of low educational levels that was six times higher than women in the high SES category, at 54·9 and 9·1 %, respectively. A significant linear trend was observed among all characteristics of households by SES categories.

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of the population by age groups in Colombia (ENSIN 2010)

* For children <5 years is mother’s educational level.

Prevalence of malnutrition (overnutrition and undernutrition) in children (<5 years)

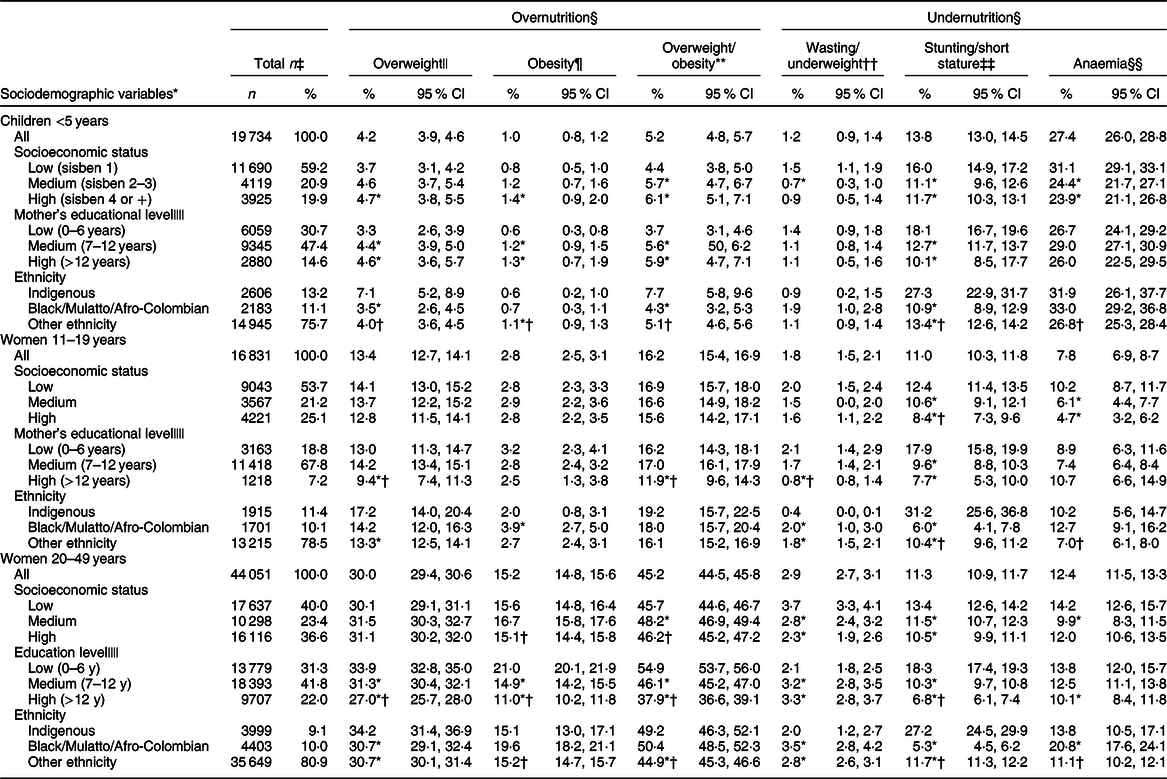

Table 2 and the Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the prevalence of malnutrition (overnutrition and undernutrition) by SES, maternal educational level and ethnicity in multivariable linear regression models. In children, the highest prevalence of malnutrition was from anaemia (27·4 %), followed by stunting (13·8 %), overweight/obesity (5·2 %) and wasting (1·2 %). In the low SES category, the prevalence of overweight/obesity was 1·4 times lower than that in the high SES category. In contrast, the prevalence of wasting, stunting and anaemia were 1·1, 1·4 and 1·3 times higher, respectively, in the low SES category than in the high SES category. Similarly, the prevalence of overweight/obesity in children was 1·6 times lower when the mother had a low educational level than when the mothers had the highest educational level. However, the prevalence of wasting, stunting and anaemia was 1·3, 1·8 and 1·0 times higher, respectively, in the low educational level than in the higher levels of education. Furthermore, indigenous children demonstrated a higher prevalence of overweight/obesity, stunting and anaemia than their counterparts from other ethnicities. Afro-Colombian exhibited a lower prevalence of overweight/obesity and stunting than their counterparts.

Table 2 Prevalence of malnutrition (overnutrition and undernutrition) by socioeconomic status (SISBEN), maternal educational level and ethnicity in Colombia (ENSIN 2010)

* P < 0·05 v. low category SEP/low education/indigenous.

† P < 0·05 v. medium category SEP/medium education/Black/Mulatto/Afro-Colombian.

‡ Weighted %.

§ Linear adjusted combinations of the estimates.

|| Overweight: BMI-for-age z score >2 and ≤3 for children <5 years; BMI-for-age z score >1 and ≤2 for women 11–19 years and BMI ≥25 and <30 for women 20–49 years.

¶ Obesity: BMI-for-age z score >3 for children <5 years; BMI-for-age z score >2 for women 11–19 years and BMI ≥30 for women 20–49 years.

** Overweight/obesity: BMI-for-age z score >2 for children <5 years; BMI-for-age z score >1 for adolescents 11–19 years and BMI ≥25 kg/m2 for women 20–49 years.

†† Wasting: Weight-for-height z score <−2 for children <5 years; underweight: BMI-for-age z score <−2 for women 11–19 years and BMI <18·5 for women 20–49 years.

‡‡ Stunting: Height-for-age <−2 for children <5 years; height-for-age z score <−2 for women 11–19 years and short stature: height <1·49 m for women 20–49 years.

§§ Anaemia: Hg adjusted using the Cohen and Haas equation <110 g/l for children <5 years and <120 g/l for women 11–49 years. The sample size for anaemia was 2155 for children <5 years; 453 for women 11–19 years and 1050 among women 20–49 years.

|||| Missing data: there was a lack of information for mother’s educational level in 7·3 and 6·1 % of the sample in children <5 years and women 11–19, respectively. Also lack of information regarding the level of education in 4·9 % of women 20–49 years.

Prevalence of malnutrition in non-pregnant adolescent women (11–19 years)

In adolescent women, the highest prevalence of malnutrition was from overweight/obesity. In the multivariate lineal regression models, the prevalence of overweight/obesity, short stature and anaemia was 1·1, 1·5 and 2·2 times higher, respectively, in the low SES category than in the highest SES category. Similarly, the prevalence of all indicators of malnutrition (i.e. overweight/obesity, wasting and short stature) was higher in adolescents of mothers with lowest educational level than in those adolescents of mothers with higher educational level. Furthermore, indigenous non-pregnant adolescent women had a higher prevalence of overweight/obesity and short stature, while Afro-Colombian women had a higher prevalence of wasting and anaemia than their counterparts.

Prevalence of malnutrition in non-pregnant adult women (20–49 years)

In adult women, the highest prevalence of malnutrition was from overweight/obesity. Nevertheless, the prevalence of overweight/obesity in adult women was 64·2 % higher (2·8 times) than in adolescent women. In multivariable linear regression models, adult women with a lower SES had higher prevalence of wasting, short stature and anaemia than their counterparts. Similarly, adult women with lower educational level had a higher prevalence in all indicators of malnutrition. Furthermore, indigenous adult women had a higher prevalence of short stature, while Afro-Colombian women had a higher prevalence of overweight/obesity, wasting and anaemia than their counterparts.

Discussion

The current study provides evidence of socio-economic inequalities in Colombia reflected by differences in the prevalence of malnutrition. SES, maternal educational level and ethnicity are conditions that reflect this inequity. Children <5 years in the lowest SES category had the highest prevalence of undernutrition and the lowest prevalence of overweight/obesity. This type of inequality has been observed in other developing countries such as Iran and Haiti(Reference Kelishadi, Qorbani and Heshmat30,Reference El Mabchour, Delisle and Vilgrain31) . However, in developed countries, the highest prevalence of overweight is observed in low SEP groups(Reference Biro, Williamson and Leggett32). Childhood undernutrition (stunting and nutritional anaemia) in developed countries is, however, not a public health concern. Malnutrition still affects children from developing countries, especially in Africa, South Asia and Oceania (excluding Australia and New Zealand), where the prevalence of stunting is as high as 38·3 %(Reference de Onis, Dewey and Borghi33), and anaemia is a severe public health problem(Reference McLean, Cogswell and Egli34). The latter prevalence is a direct reflection of the inequity between developed and developing countries, which may be associated with differences in socioeconomic conditions.

From the current analysis, a special concern is that Colombian non-pregnant women of all ages from the low SES category and lower educational level exhibited the highest prevalence of being both overweight and suffering from anaemia. The anaemia result is not surprising because it is widely accepted that childbearing women are a vulnerable group due to menstruation(35). Likewise, the prevalence of overweight in women of low SES has been reported in developing countries(Reference Djalalinia, Peykari and Qorbani10).

Indigenous people and/or those Afro-Colombian had the highest prevalence of undernutrition (i.e. wasting, stunting and anaemia). A similar finding was observed in non-pregnant woman between 11 and 49 years with a low SES for conditions of malnutrition (over- and undernutrition). Thus, it is necessary to highlight the importance of analysing epidemiologic data with inequality as the focus to identify vulnerable populations.

The coexistence of conditions related to both over- and undernutrition at the population level, which has been identified as DBM(1), should be highlighted. Further, DBM has been observed at the family and individual levels. In Colombia, the prevalence of DBM at the family level is 5·1 %, while it is 0·1 % at the individual level in children under 5 years and is 3·4 % in non-pregnant 13–49-years-olds(Reference Sarmiento and Parra19). Despite the low DBM prevalence reported, a national average may mask inequities related to DBM. In the current study, children with a low SES, mothers with low levels of education and indigenous peoples, and those Afro-Colombian had a higher prevalence of wasting, stunting and anaemia compared with their counterparts. These results suggest that public policies should address all forms of malnutrition in the most vulnerable populations using multiple strategies.

In Colombia, strategies were implemented to achieve the United Nation’s millennium developmental goals from 1990 to 2015, including the reduction of hunger(Reference Bogotá36). Accordingly, in children <5 years, the prevalence of stunting decreased from 26·1 % in 1990 to 13·2 % in 2010, and the prevalence of underweight decreased from 8·6 to 3·4 % in the same period(18). However, as we observed in the current study, children with a low SES, mothers with a low level of education, indigenous people and those Afro-Colombian still demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence of wasting, stunting and anaemia compared with their counterparts. Conversely, the prevalence of overweight increased from 3·1 % in 2005 to 5·2 % in 2010, which is consistent with micronutrient deficiencies(Reference Cediel Giraldo, Castaño Moreno and Gaitán Charry37).

Evidence from the nutritional transition in Colombia indicates that although overweight/obesity continues to be more prevalent among high-income Colombian households, it is growing at a faster pace among the most economically disadvantaged(Reference Parra, Iannotti and Gomez38). Our study of non-pregnant adolescent and adult women (between 11 and 49 years) showed similar results, where those with a lower SES and low levels of education experienced the worst scenario, namely, having the highest prevalence for both types of malnutrition (undernutrition (wasting, stunting and anaemia) and overweight/obesity). Accordingly, a recent analysis has also shown that the DBM in Colombia coexists at the national, household and intra-individual levels(Reference Sarmiento and Parra19,Reference Parra, Gomez and Iannotti39,Reference Parra, Gomez and Iannotti40) . Furthermore, the double DBM has been associated with poverty in developing countries(Reference Delisle, Batal and Renier41).

Some of the social determinants of malnutrition in Latin America are SES, level of education, sex and ethnicity. These determinants explain nearly all situations of marginalisation or exclusion in societies and serve as strong markers for the junctures of malnutrition(Reference Jiménez-Benítez, Rodríguez-Martín and Jiménez-Rodríguez42). Our results are consistent with results from a study conducted a decade ago that investigated the roles individual, household and community level characteristics in the socioeconomic inequalities of malnutrition among children and adolescents in Colombia. In that study, maternal education and access to sanitation explained stunting, while maternal and household characteristics explained the socioeconomic disparities of overweight(Reference Garcia, Sarmiento and Forde20). However, in the current study, ethnicity was, for the first time, included as a factor that demonstrated an association with the highest prevalence of malnutrition.

Our results represent an important discussion point for the public health agenda in Colombia. The country is presently experiencing a historical moment of peace after more than half a century of conflict that is believed to have cost the lives of 220 000 people and displaced more than six million(43). The consequences of that conflict created an environment of social inequality, where deaths from undernutrition (wasting) among the most socially disadvantaged children are still occurring(Reference Quiroga44,45) . Concurrently, the population in the main cities experience the DBM(Reference Sarmiento and Parra19). Thus, it is an important and historical moment in Colombia, where resources previously co-opted for use in the conflict, must now shift to agricultural programmes, social reconstruction and improving the nutritional status of the population. This shift must take into account the idea that ‘food is a right, not a commodity’ and focus on supplying healthy food products for the entire population, especially to those who are the most disadvantaged (i.e. children, non-pregnant women and indigenous and Afro-Colombian living in low socioeconomic conditions).

Actions undertaken by The National Policy on Food and Nutrition Security from 2014 to 2018 by the ‘Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar (ICBF)’ are focused on ensuring that the population has access to and consumes food in a stable and timely manner and with sufficient quantity, variety, quality and safety(46). Important strengths of the current policies to prevent undernutrition or overweight in Colombia appear to be their inter-sectorial nature, their focus on well-being and quality of life as a whole and not on individual aspects of health or nutritional status, as well as an emphasis on prevention through lifestyle and community interventions(47). However, it is important to underscore that current policies require adequate implementation with the coordination of entities working both sides of the problem to optimise resources and ensure that specific policies are not contributing to worsening other health problems.

The main strength of the current study is the use of a nationally representative sample that includes anthropometric and sociodemographic indicators. The results of our study can be used as a baseline for the nutritional conditions of vulnerable populations previous to the current peace process and will allow us to contrast that situation with nationally representative samples following the implementation of the peace agreements, social reconstruction and the end of conflict in Colombia. The main limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the study, which does not enable us to infer causality/directionality of the association between sociodemographic status and malnutrition. However, these results represent the first study with nationally representative data that show the socioeconomic inequalities of malnutrition in vulnerable populations from Colombia.

Conclusion

The current study showed evidence of socioeconomic inequalities of malnutrition (under- or overnutrition) in Colombian children <5 years and non-pregnant (adolescent and adult) women. These results suggest that public policies regarding nutrition must shift focus from undernutrition programmes to multiple strategies to address all forms of malnutrition in the most vulnerable populations.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The ‘Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar’ (ICBF) and PROFAMILIA provided support and allowed the use of ENDS/ENSIN data base. The authors would like to thank the Latin American Nutrition Leadership Program (LILANUT Program) for the coordination of the project ‘Malnutrition in all its forms for wealth, education and ethnicity in Latin America: Who is affected the most?’, to which this article makes part. Financial support: The current study has financial support from the ‘grupo de determinantes sociales y economicos de la nutrición’, of the school of nutrition and dietetics from the University of Antioquia. Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article. Authorship: G.C. took care of data management and analyses. G.C., E.P., D.G., O.S. and L.G. interpreted the data. G.C. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read, edited and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019004257.