The prevalence of obesity among adults in the UK is increasing( Reference Moody 1 ). Evidence has been presented to Military Command demonstrating that the UK Armed Forces are not immune to this obesity epidemic( Reference Bennett, Brasher and Bridger 2 – Reference Wood 5 ). This is of concern due to the inherent health( Reference Bridger, Munnoch and Dew 6 ), occupational( Reference Bridger, Brasher and Bennett 7 , Reference McLaughlin and Wittert 8 ) and economic risks( Reference Dall, Zhang and Chen 9 ) that this poses to the UK Armed Forces. Although the causes of overweight and obesity are complex and multifaceted, unhealthy diets and physical inactivity have been identified as major contributing factors( Reference Martinez 10 , Reference Prentice and Jebb 11 ) and should therefore be targeted in interventions which aim to reduce the prevalence of obesity among Service personnel.

Workplaces have been recognised as important settings for health promotion and disease prevention( 12 , 13 ). Interventions delivered in the workplace can offer an effective means of influencing the health behaviours of a broad captive audience through multiple levels of influence, by means of direct (e.g. health education and increasing opportunities for physical activity) or indirect efforts (e.g. changing social norms to promote healthier behaviours)( Reference Quintiliani, Sattelmair and Sorensen 14 ).

There is an expanding evidence base that workplace interventions can improve the dietary( Reference Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 15 – Reference Hutchinson and Wilson 18 ) and physical activity behaviours of employees( Reference Kahn-Marshall and Gallant 17 – Reference Engbers, van Poppel and Paw 21 ), which in turn may improve health and work-related outcomes( Reference Conn, Hafdahl and Cooper 19 ). However, the majority of reviews to date have focused on the effects of individual-level strategies (e.g. education) with few reviewing the effects of policy and environmental changes. As such, questions remain regarding the effectiveness of interventions which target multiple levels of the social system, where it is recognised that interventions targeting behaviour change are successful and sustainable only if the physical and social environments in which they are embedded are supportive( Reference Kahn-Marshall and Gallant 17 , Reference Glanz, Rimer and Viswanath 22 – Reference Sallis, Cervero and Ascher 25 ).

Service personnel live and work in closed, semi-closed and open environments, where the level of constraint on their health behaviours is dependent upon the type and location of the establishment in which they are based. In a number of military establishments (e.g. onboard a warship) the environment is distinct from a traditional workplace, with Service personnel being a captive audience whose food and physical activity choices are constrained by the environment (i.e. a closed environment). A systematic review specifically evaluating environmental-based strategies targeted at improving the health behaviours of adults in such closed environments is lacking. Thus, the present systematic review aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, which included environmental strategies, aimed at improving the dietary and physical activity behaviours of adults in institutions (e.g. military establishments or ships). Specifically, it sought to determine which strategies were associated with improvements in diet, physical activity and body composition indices.

Methods

PROSPERO registration

The protocol for the present systematic review was registered on PROSPERO (registration number CRD42017076709) on 13 October 2017.

Literature search

The present systematic review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement( Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff 26 ). Using Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and text words, the following databases were searched for studies from database inception to October 2017: MEDLINE; Embase; PsycINFO; CINAHL; The Cochrane Library; Web of Science; ProQuest Dissertation and Theses; and Scopus. The reference lists of all identified reports and articles were searched for additional studies. An advanced search was conducted in Athena. Searches were limited to literature published in English. The strategy included a search for the following terms: Institutional Setting: (); AND Health Behaviour/Health Outcome: (); AND Intervention: () (see the online supplementary material).

Study inclusion/exclusion criteria

For a study to be included it needed to evaluate an intervention, comprising environmental changes, aimed at improving dietary intake and/or physical activity behaviours. The environmental intervention(s) had to comply with Hollands et al.’s( Reference Hollands, Shemilt and Marteau 27 ) definition of environmental interventions, have been conducted within an institutional setting (e.g. military establishments, ship or prison), in a high-income economy as defined by the World Bank Group( 28 ) and have targeted adults aged 18–64 years. Eligible interventions could be targeted at adults of any body composition, with or without identified risk factors or conditions. Studies were excluded if the focus was surgical or pharmaceutical.

Outcomes

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported the effects of the intervention on behavioural measures of physical activity behaviour and dietary intake or physiological measures associated with these behaviours. Primary outcomes were objective and subjective measures of physical activity behaviour and dietary intake. Secondary outcomes were objective and subjective measures of changes in body composition indices.

Study selection process

All potentially relevant abstracts were imported into Endnote and any duplicates were removed. The titles and abstracts of the remaining studies were screened by one reviewer (A.M.S.) and were scored as follows: ‘positive’ (if inclusion and exclusion criteria were certainly met); ‘negative’ (if inclusion and exclusion criteria were certainly not met); or ‘unclear’ (if the reviewer was unsure or if not enough detail was provided in the abstract to make a clear decision). The full text of articles scored as ‘positive’ or ‘unclear’ was retrieved and assessed for eligibility by two review authors (A.M.S. and E.L.P.). Discrepancies between the two authors were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (S.A.W.). The reference lists of the included articles were manually searched for additional articles.

Study design

Data were included from controlled trials (with or without randomisation), before-and-after (BA) studies and cohort studies, where comparators could be other interventions or no treatment. Studies were categorised by study design using the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines( 29 ).

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

A standardised data extraction form was completed for all eligible studies. Data were recorded on study design, setting, intervention type, participant and intervention characteristics, study outcome measures and reported results. Depending on the study design, either the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool( Reference Higgins, Altman and Gøtzsche 30 ) or the risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions (ROBINS-I) tool( Reference Sterne, Hernan and Reeves 31 ) was used to assess potential biases in the included studies. The template for intervention description and replication checklist (TIDieR)( Reference Hoffmann, Glasziou and Boutron 32 ) was used to evaluate the quality of reporting of the interventions, the typology of choice architecture interventions( Reference Hollands, Shemilt and Marteau 27 ) was used to classify the types of environmental intervention, and the behaviour change technique taxonomy v1( Reference Michie, Richardson and Johnston 33 ) was used to classify the types of behaviour change techniques that were employed in the interventions. Two review authors (A.M.S. and E.L.P.) extracted the information from all retrieved articles. Discrepancies between the two authors were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (S.A.W.).

Data analysis

Meta-analysis was not possible due to the considerable heterogeneity in the design and quality of the studies, the types of interventions and outcomes measured. As such, a narrative summary of the results for each study is presented. Where possible, data provided were used to calculate and report standardised effect sizes for mean differences using a calculator provided by the Campbell Collaboration( Reference Wilson 34 ). Effect sizes were used to quantify the size of the difference between two groups, such that the effectiveness of an intervention could be determined.

Results

Literature search

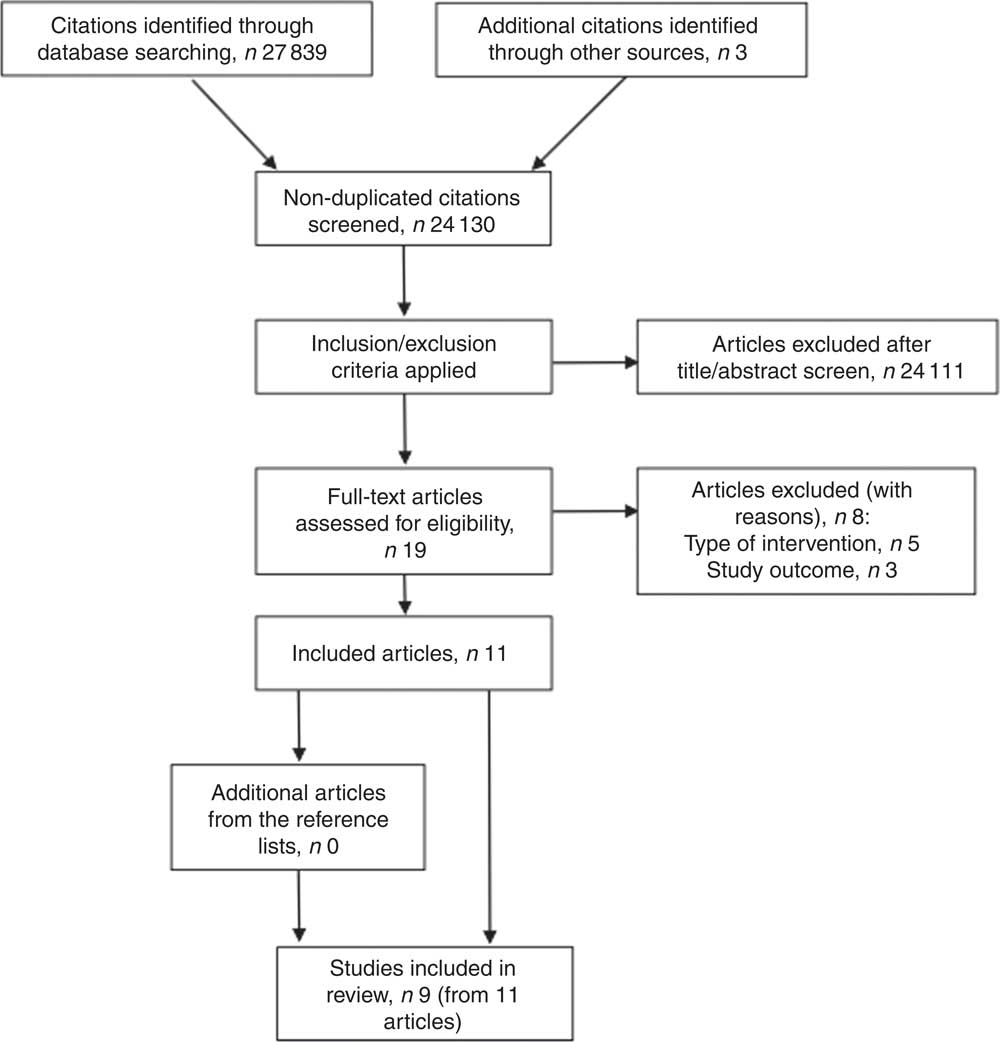

The search identified 27842 potentially relevant articles. After the removal of duplicates, 24130 articles remained. Of these articles, 24111 were excluded following screening the titles, abstracts or both against the study inclusion and exclusion criteria. After full-text assessment of the nineteen remaining articles, eight articles were excluded because they did not meet one or more of the inclusion criteria. Checking the references of the eleven remaining articles produced no additional articles. Nine studies (reported in eleven articles) were included in the systematic review( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 – Reference Fiedler, Cortner and Ktenidis 45 ). Figure 1 presents a flowchart of the study selection process.

Fig. 1 Flowchart of study selection process for the present review on environmental interventions to promote healthier eating and physical activity behaviours in institutions

Study characteristics

Descriptions of the included studies are provided in Table 1. Studies were published between 1995 and 2016. The studies were conducted in the USA (n 5)( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 , Reference Crombie, Funderburk and Smith 37 , Reference Friedl, Klicka and King 38 , Reference Sproul, Canter and Schmidt 41 , Reference Fiedler, Cortner and Ktenidis 45 ), Denmark (n 2)( Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 , Reference Lassen, Thorsen and Trolle 40 , Reference Thorsen, Lassen and Tetens 42 ), Finland (n 1)( Reference Bingham, Lahti-Koski and Puukka 36 ) and Norway (n 1)( Reference Uglem, Kjollesdal and Frolich 43 , Reference Uglem, Stea and Kjollesdal 44 ). Settings included military bases (n 8)( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 – Reference Friedl, Klicka and King 38 , Reference Lassen, Thorsen and Trolle 40 – Reference Fiedler, Cortner and Ktenidis 45 ) and a shipping company (n 1)( Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 ). Study sizes ranged from 148 to 606 and from one to ten settings. There was a range of different study designs: one randomised controlled trial( Reference Fiedler, Cortner and Ktenidis 45 ), one cluster-randomised controlled trial( Reference Crombie, Funderburk and Smith 37 ), four non-randomised controlled trials( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 , Reference Bingham, Lahti-Koski and Puukka 36 , Reference Friedl, Klicka and King 38 , Reference Uglem, Kjollesdal and Frolich 43 , Reference Uglem, Stea and Kjollesdal 44 ) and three BA studies( Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 – Reference Thorsen, Lassen and Tetens 42 ).

Table 1 Summary of studies included in the present review on environmental interventions to promote healthier eating and physical activity behaviours in institutions

BA, before and after; RCT, randomised controlled trial; DFAC, dining facility; CTL, control; INT, intervention; B, baseline; 6M, 6 months; 12M, 12 months; DQI, diet quality index; WC, waist circumference; F&V, fruit and vegetables; EI, energy intake; CHO, carbohydrates; FU, follow-up; IE, intervention effect; TE, time effect.

Risk of bias

The risk of confounding bias (see Table 2 for an overview) was considered serious in two articles, moderate in four and low in three. Selection bias was considered moderate in four articles, low in five and unclear in two due to incomplete reporting. Allocation concealment, performance and detection bias were considered unclear due to incomplete reporting in the two articles assessed for these types of bias. Classification of intervention bias was considered low in all articles assessed (n 9). Deviation from intended intervention bias was considered serious in one article and low in eight. Attrition bias was considered serious in one article, moderate in five, low in four and unclear in one due to incomplete reporting. Outcome measurement bias was considered moderate in all articles assessed (n 9). Reporting bias, reflecting on whether the outcomes reported were pre-planned, was considered low in all the articles assessed (n 11). Risk of other bias not covered elsewhere was considered low in the two articles assessed.

Table 2 Risk of bias in studies included in the present review on environmental interventions to promote healthier eating and physical activity behaviours in institutions

n/a, not applicable for type of study.

Risk of bias assessed using the risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions (ROBINS-I) tool, except where noted otherwise.

* Risk of bias assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool.

Descriptions of the interventions

Of the nine interventions described in the eleven included articles, five were multicomponent( Reference Bingham, Lahti-Koski and Puukka 36 , Reference Crombie, Funderburk and Smith 37 , Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 , Reference Lassen, Thorsen and Trolle 40 , Reference Thorsen, Lassen and Tetens 42 – Reference Uglem, Stea and Kjollesdal 44 ) and four included environmental changes only( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 , Reference Friedl, Klicka and King 38 , Reference Sproul, Canter and Schmidt 41 , Reference Fiedler, Cortner and Ktenidis 45 ). The most commonly used strategies were making healthy changes to food content and/or options (n 7)( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 – Reference Friedl, Klicka and King 38 , Reference Lassen, Thorsen and Trolle 40 , Reference Thorsen, Lassen and Tetens 42 – Reference Fiedler, Cortner and Ktenidis 45 ), introducing health promotion information and/or education (n 4)( Reference Bingham, Lahti-Koski and Puukka 36 , Reference Crombie, Funderburk and Smith 37 , Reference Sproul, Canter and Schmidt 41 , Reference Uglem, Kjollesdal and Frolich 43 , Reference Uglem, Stea and Kjollesdal 44 ), labelling food items (n 3)( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 , Reference Bingham, Lahti-Koski and Puukka 36 , Reference Sproul, Canter and Schmidt 41 ) and introducing cooking courses for canteen staff (n 2)( Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 , Reference Lassen, Thorsen and Trolle 40 , Reference Thorsen, Lassen and Tetens 42 ). Few interventions attempted to improve fitness facilities (n 1)( Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 ), offer individual exercise guidance (n 1)( Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 ) and offer individual health check-ups (n 1)( Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 ). Duration of follow-up ranged from 3 weeks to 10 years.

According to Hollands et al.’s typology (Table 3), eight interventions primarily altered the placement of objects or stimuli (n 8 availability (i.e. adding behavioural options within an environment))( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 – Reference Lassen, Thorsen and Trolle 40 , Reference Thorsen, Lassen and Tetens 42 – Reference Fiedler, Cortner and Ktenidis 45 ), four primarily altered the properties of objects or stimuli (n 3 labelling (i.e. applying labelling or endorsement information to product or at point of choice)( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 , Reference Crombie, Funderburk and Smith 37 , Reference Sproul, Canter and Schmidt 41 ) and n 1 presentation (i.e. altering sensory qualities or visual design of the product))( Reference Lassen, Thorsen and Trolle 40 , Reference Thorsen, Lassen and Tetens 42 ) and one altered both the properties and placement of objects or stimuli through prompting (i.e. using non-personalised information to promote or raise awareness of a behaviour)( Reference Uglem, Kjollesdal and Frolich 43 , Reference Uglem, Stea and Kjollesdal 44 ).

Table 3 Classification, according to the Hollands et al. ( Reference Hollands, Shemilt and Marteau 27 ) emergent typology of choice architecture interventions, of studies included in the present review on environmental interventions to promote healthier eating and physical activity behaviours in institutions

N, absence of intervention type; Y, presence of intervention type.

The most frequently used behaviour change technique was restructuring the physical environment (n 8 (e.g. healthy changes to food options))( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 – Reference Lassen, Thorsen and Trolle 40 , Reference Thorsen, Lassen and Tetens 42 – Reference Fiedler, Cortner and Ktenidis 45 ), followed by using prompts/cues (n 3)( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 , Reference Crombie, Funderburk and Smith 37 , Reference Sproul, Canter and Schmidt 41 ) and using information about health consequences (n 2)( Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 , Reference Uglem, Kjollesdal and Frolich 43 , Reference Uglem, Stea and Kjollesdal 44 ). Only one intervention used feedback on behaviour, biofeedback, feedback on outcome(s) of behaviour, social support, information on how to perform a behaviour and demonstration of behaviour( Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 ).

Intervention reporting

According to the TIDieR checklist( Reference Hoffmann, Glasziou and Boutron 32 ) (Table 4), all included articles specified the name of the intervention (‘brief name’), described the rationale (‘why’), reported the procedures applied (‘what’, ‘procedures’), described the mode of delivery (‘how’), described the location in which the intervention occurred (‘where’), and described the period of time over which the intervention was delivered, or the dose or intensity of the intervention (‘when and how much’). All articles except one described the materials used (‘what’, ‘materials’). Four out of the nine articles did not adequately report who had delivered the intervention (‘who provided’). Only one article reported whether the intervention was modified during the study (‘modifications’), whether the intervention was tailored (‘tailoring’) and the actual adherence/fidelity (‘how well’, ‘actual’). None of the articles reported the planned strategies for ensuring adherence/fidelity (‘how well’, ‘planned’).

Table 4 Coding, against TIDieR criteria( Reference Hoffmann, Glasziou and Boutron 32 ), of studies included in the present review on environmental interventions to promote healthier eating and physical activity behaviours in institutions

TIDieR, template for intervention description and replication checklist.

X means no information provided, number indicates article page number.

Outcomes: effects of interventions

All nine interventions reported measures of dietary intake and one reported measures of physical activity. Dietary intake was measured objectively through sales data, digital photography/plate waste methods and weighed food intake in four interventions( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 , Reference Crombie, Funderburk and Smith 37 , Reference Lassen, Thorsen and Trolle 40 – Reference Thorsen, Lassen and Tetens 42 ), and was based on self-reported data in five interventions( Reference Bingham, Lahti-Koski and Puukka 36 , Reference Friedl, Klicka and King 38 , Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 , Reference Uglem, Kjollesdal and Frolich 43 – Reference Fiedler, Cortner and Ktenidis 45 ). Physical activity level was based on self-reported data( Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 ). Three of the nine interventions reported measures of body composition( Reference Friedl, Klicka and King 38 , Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 , Reference Fiedler, Cortner and Ktenidis 45 ). Two of these reported metabolic factors( Reference Friedl, Klicka and King 38 , Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 ). Other outcome measures reported included self-reported acceptability and satisfaction of changes (n 4)( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 , Reference Crombie, Funderburk and Smith 37 , Reference Uglem, Stea and Kjollesdal 44 , Reference Fiedler, Cortner and Ktenidis 45 ), physical fitness (n 2)( Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 , Reference Fiedler, Cortner and Ktenidis 45 ) and nutrition knowledge (n 1)( Reference Uglem, Kjollesdal and Frolich 43 , Reference Uglem, Stea and Kjollesdal 44 ).

For the primary outcomes, of the four interventions that measured energy and nutrient intakes, all four reported significant positive effects. Effect sizes could be calculated for three interventions; Cohen’s d ranged from 0·05 to 1·10 (no effect to a large-sized effect). Of the eight interventions that measured food intake and/or food selection quality, seven reported significant positive effects. However, one of these interventions reported no effects on some measures( Reference Crombie, Funderburk and Smith 37 ) and one reported negative effects on some measures, including fruit intake( Reference Bingham, Lahti-Koski and Puukka 36 ). Effect sizes could be calculated for three interventions; Cohen’s d ranged from 0·11 to 1·42 (no effect to a large-sized effect). No significant effects were reported in the intervention that measured physical activity levels. For the secondary outcomes, none of the three interventions that measured body composition indices reported significant effects. Of the two interventions that measured metabolic factors, one reported a trend to support a more favourable lipid profile and one reported a significant reduction in participants with metabolic syndrome.

For the other outcomes, of the four interventions that measured self-reported satisfaction, two reported significant positive effects. Effect sizes could be calculated for one intervention; Cohen’s d was 0·19 (no effect). One out of the two interventions that measured physical fitness reported a significant positive effect, and a significant positive effect was reported in the one intervention that measured nutrition knowledge. Effect sizes could not be calculated for these measures.

For the eight interventions which altered the placement of objects or stimuli through increasing the availability of healthier food options( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 – Reference Lassen, Thorsen and Trolle 40 , Reference Thorsen, Lassen and Tetens 42 – Reference Fiedler, Cortner and Ktenidis 45 ), the effects did not differ from the overall findings.

Of the three interventions which applied labelling to foods at the point of choice( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 , Reference Crombie, Funderburk and Smith 37 , Reference Sproul, Canter and Schmidt 41 ), two interventions reported significant positive effects on energy and nutrient intakes (effect sizes d = 0·05–0·65, no effect to medium-sized effect), food intake and/or food selection quality (effect sizes d = 0·11–1·42, no effect to large-sized effect) and self-reported satisfaction (effect size d = 0·19 (one intervention), no effect). One of the three interventions reported no significant effects on some measures of food intake( Reference Crombie, Funderburk and Smith 37 ). There were no differences in the sales of targeted entrées in the intervention by Sproul et al. ( Reference Sproul, Canter and Schmidt 41 ), with 79 % of respondents reporting that the materials did not influence their food selection.

The one intervention that improved the presentation of healthier food options( Reference Lassen, Thorsen and Trolle 40 , Reference Thorsen, Lassen and Tetens 42 ) reported significant positive effects on food intake (effect size d = 1·40, large-sized effect). The one intervention that used prompting( Reference Uglem, Kjollesdal and Frolich 43 , Reference Uglem, Stea and Kjollesdal 44 ) reported significant positive effects on food intake and nutrition knowledge (no effect size calculated), but no changes in self-reported satisfaction.

Discussion

The aim of the present review was to systematically examine the effectiveness of interventions, which included environmental strategies, aimed at improving the dietary and physical activity behaviours of adults in institutions. The current evidence base appears to be in favour of implementing environmental interventions in institutions to improve the dietary behaviours of adults. However, it was difficult to draw conclusions concerning the effectiveness of environmental interventions on improving physical activity behaviours or body composition indices, or to make clear recommendations about the content and delivery of interventions, due to the small number of studies and the variable methodological quality of the studies and intervention reporting included in the review.

Across the nine interventions included, eight produced significant positive effects on dietary behaviours. Reported effects included: decreased energy intake; decreased percentage energy from fat and saturated fat, and increased percentage energy from carbohydrates; positive changes in the number of red- and green-labelled items purchased; reductions in the proportion of participants reporting frequent intakes of high-sugar products; and increases in fruit and/or vegetable consumption. Effect sizes could not be calculated for all studies. Where they could be calculated, there was considerable variation between and within studies, with effect sizes ranging from no effect to large-sized effects. Only one of the nine interventions used strategies to improve physical activity levels( Reference Hjarnoe and Leppin 39 ). There was a significant positive effect on physical fitness but no effect on self-reported activity levels. A possible reason for the lack of effectiveness was poor fidelity: less than half of the ships included in the study reported actual improvements in fitness facilities; and less than a third of participants reported receiving exercise guidance.

No evidence was identified that the interventions included in the review resulted in significant positive changes in body measurement and/or body composition indices, although this was measured in only one-third of the studies. A possible explanation for this is that extensive lifestyle changes are required to affect body composition. Compensatory behaviours (e.g. dietary intake at the evening meal) were not measured in any of the included studies. Thus, although the interventions improved the dietary behaviours of participants during the meal times assessed, it was unknown whether this led to compensatory behaviours at other meals or between meals (e.g. snacking behaviour).

Similar to the findings reported by Allan et al.( Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 46 ), the types of intervention strategies most commonly employed in the interventions included in the review were increasing the availability of healthier options and food labelling. Only one intervention altered the presentation of foods on offer, and one introduced prompts to the environment. The interventions included in the review contained between one and five different components. Four of the interventions used environmental strategies only, and five used multilevel strategies. This made it difficult to identify precisely what worked and for whom. As positive effects on dietary behaviours were reported in eight out of nine of the interventions, it could be assumed that all types of environmental strategies applied across the interventions were successful to some degree and that potentially it was the multilevel and multicomponent nature of the interventions that was successful.

In the study that reported no significant positive effects( Reference Sproul, Canter and Schmidt 41 ), labelling and health promotion information focusing on health attributes were used unsuccessfully to increase sales of healthier meal options. The authors suggested that a better strategy would have been to highlight the sensory attributes of healthier foods such as taste and quality. In contrast, two other interventions included in the review that used point-of-purchase labelling reported positive effects. These interventions used multiple environmental strategies. As such, it cannot be determined whether food labelling per se was a successful strategy.

The duration of follow-up in the studies ranged from 3 weeks to 10 years, with less than half of the studies incorporating follow-up times of 1 year or longer. One of the studies that included two follow-up points reported that, at the second follow-up point at 5 years, there was a failure to sustain the increase in fruit and vegetable intake that was achieved at the first follow-up point( Reference Thorsen, Lassen and Tetens 42 ). To determine the duration of beneficial effects after an intervention has ended long-term follow-up studies are required( Reference Kahn-Marshall and Gallant 17 , Reference Harden, Peersman and Oliver 47 ).

Comparison with other reviews

The findings from the present systematic review are broadly comparable with those of other reviews undertaken in a workplace setting. The present and previous reviews have reported that health promotion interventions that include environmental strategies have a positive effect on dietary behaviours( Reference Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 15 – Reference Kahn-Marshall and Gallant 17 , Reference Engbers, van Poppel and Paw 21 , Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 46 , Reference Maes, Van Cauwenberghe and Van Lippevelde 48 – Reference Matson-Koffman, Brownstein and Neiner 50 ). As in the present review, Engbers et al. ( Reference Engbers, van Poppel and Paw 21 ) reported inconclusive evidence for an effect on physical activity, whereas other reviews( Reference Kahn-Marshall and Gallant 17 , Reference Schröer, Haupt and Pieper 49 , Reference Matson-Koffman, Brownstein and Neiner 50 ) have reported that multicomponent interventions incorporating individual-level and environmental strategies improved physical activity behaviours. Similar to the present review, the reviews undertaken by Allan et al. ( Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 46 ) and Engbers et al. ( Reference Engbers, van Poppel and Paw 21 ) reported little evidence that health promotion interventions have an effect on body composition indices. Conversely, other reviews have reported that interventions achieved modest improvements in weight status, which might be explained by these reviews including studies where changes in weight was a primary outcome( Reference Schröer, Haupt and Pieper 49 , Reference Anderson, Quinn and Glanz 51 , Reference Verweij, Coffeng and van Mechelen 52 ).

In the present review, the most commonly used environmental strategies were increasing the availability of healthier options and food labelling. This was also the case in the review undertaken by Allan et al. ( Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 46 ). Due to the numerous strategies that were employed by the interventions in the present review, it is difficult to identify precisely what worked and for whom. Previous reviews have also reported that it is difficult to determine the effective components of interventions and suggest that interventions should be multilevel and multicomponent( Reference Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 15 , Reference Kahn-Marshall and Gallant 17 , Reference Engbers, van Poppel and Paw 21 , Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 46 , Reference Schröer, Haupt and Pieper 49 , Reference Verweij, Coffeng and van Mechelen 52 ).

Methodological quality of studies

Only two out of the nine studies employed a randomised or cluster-randomised controlled design. The quality assessment indicated several common methodological limitations across the studies, which were common to previous workplace reviews( Reference Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 15 – Reference Kahn-Marshall and Gallant 17 , Reference Engbers, van Poppel and Paw 21 , Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 46 , Reference Maes, Van Cauwenberghe and Van Lippevelde 48 ). A possible explanation of this is due to studies being performed in institutions, where organisational and logistical problems may have compromised the strength of the research design. A particular cause for concern was the use of self-reported methods of outcome measurement, where five out of the nine studies used self-reported measures of behaviour. This may have caused recall or reporting bias and resulted in no blinding of the outcome assessment. Other issues with using self-report methods to measure dietary and physical activity behaviours are that it takes time and effort to complete diaries, which may be an intervention in itself (self-monitoring) and may therefore obscure the impact of the intervention. Future research should therefore use valid and reliable measures to assess behaviours and where possible use these in combination with objective measures.

Other limitations of the studies included the: lack of concealed intervention allocation; lack of assessment of compensatory behaviours; variable reporting quality including insufficient reporting of effect sizes (or data to allow their calculation); and the absence of intention-to-treat analyses, which may have led to the under- or overestimation of effects. There were also sampling limitations and the lack of use of validated questionnaires in some of the studies. Generalisation of the findings to other contexts is limited by the fact that all the studies were conducted in the USA or Northern European countries. This highlights the need for further well-designed evaluation studies.

The impact of an intervention is maximised when attrition is low. In the present review there was considerable variation in attrition bias between the included studies. It is important that strategies are identified to sustain participant involvement. This could be achieved by exploring the feasibility and acceptance of interventions and including some involvement from the target population during the development of the intervention, which was the case in three of the studies included in the review. Self-reported satisfaction was measured in two out of five of the studies that were classified as having a moderate to serious risk of attrition bias( Reference Belanger and Kwon 35 , Reference Uglem, Kjollesdal and Frolich 43 , Reference Uglem, Stea and Kjollesdal 44 ). In one study there was no effect of the intervention on satisfaction and in the other study food appeal rating increased after the intervention, suggesting that attrition was not a result of the intervention itself.

One notable finding from the coding of the interventions against TIDieR guideline recommendations was that the majority of studies failed to report planned or actual strategies to assess adherence or fidelity. Fidelity is an important component of programme evaluation, which enables researchers and practitioners to understand how and why an intervention works, and the extent to which outcomes can be improved.

Limitations

Limitations of the present review should be taken into account when interpreting the findings. One potential limitation is the literature search. The search was limited to articles published in the English language, which may have resulted in relevant studies published in other languages being missed. Second, it is possible that the search did not identify all published studies, which might have resulted in selection bias. This was minimised by checking the references of the articles retrieved in the search. A third issue that should be considered is publication bias due to selective publishing of studies demonstrating positive outcomes. A further limitation of the present review was that the heterogeneity of design, interventions and outcome measures negated a quantitative synthesis of results by meta-analysis. In addition, effect sizes could not be calculated for all studies or all measured variables.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the evidence base appears to be in favour of implementing environmental-based interventions in institutions to improve the dietary behaviours of adults. However, due to the multilevel and multicomponent nature of the intervention studies it is difficult to determine which strategies were successful and which were not. Environmental strategies that were typically employed in the interventions targeted reducing barriers, increasing opportunities for and accessibility of healthy choices, restricting the availability of less healthy options, and increasing cues to healthy behaviour.

It is difficult to draw conclusions concerning the effectiveness of environmental-based interventions at improving the physical activity behaviours or the body composition indices of adults in institutions. Furthermore, it is difficult to make clear recommendations about the content and delivery of environmental-based interventions that aim to improve the dietary and physical activity behaviours and body composition indices of adults in institutions, due to the small number of studies included in the review and the variable methodological quality of the studies and intervention reporting. Further well-designed evaluation studies are required.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This study was funded by the UK Ministry of Defence (MOD). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the UK Government or the MOD. Conflict of interest: None of the authors had any conflicts of interest. Authorship: A.M.S. formulated the research question(s), designed the study, collected and analysed the data, and prepared the manuscript. S.A.W. formulated the research question(s), designed the study and prepared the manuscript. J.L.F. formulated the research question(s) and prepared the manuscript. A.J.A. prepared the manuscript. E.L.P. formulated the research question(s), designed the study, analysed the data and prepared manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003683