The online public sphere matters. Digital communication technologies and platforms increasingly shape the world's politics, society, economics, and culture – and the Middle East is no exception.Footnote 2 The six states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) have some of the highest rates of internet penetration in the Middle East (between 93–100% of the national population) and also some of the highest rates of social media use, including Twitter.Footnote 3 Nonetheless, the online public sphere and the ways in which digital media platforms influence societal and political discourse are an understudied area of research in the Gulf.Footnote 4

Across disciplines, academics are increasingly recognizing the relevance of the online public sphere as a venue for communication and manipulation of information and preferences, such as important work done in the political science field on the content and weaponization of digital media platforms in the Middle East region.Footnote 5 The field of information communication technology provides further insights on the efficiency of social media as communication tools between political entities and their publics, enabling unprecedented citizen participation and interaction but also contributing to the spread of the political powers’ discourse.Footnote 6 And in media studies, social media are also seen as ways of mobilizing public sentiment and organizing collective action to achieve common goals, including governmental transparency, protection of human rights, and improved socioeconomic conditions.Footnote 7 Yet while the Arab Spring and the Iran election protests were seen as Twitter-spurred uprisings by many observers,Footnote 8 digital media has also been used by regimes as tools of monitoring and repression, such as in BahrainFootnote 9 and Saudi Arabia.Footnote 10 Further, major investment in digital platforms such as Twitter by Saudi Arabia raises concerns about company neutrality in its practices and policies.Footnote 11

These disparate disciplines converge on the realization that the online public sphere provides both promise and danger to societal engagement, discourse, and networking, especially in authoritarian regimes. In these types of regimes, where physical public space is tightly controlled and/or inaccessible, the internet can serve as an alternative public square.Footnote 12 But trolls and bots, often encouraged or hired by political authorities, can hijack the online public sphere and drown out alternative and anti-establishment voices through targeted and purposeful campaigns of disinformation – a rising trend that has been documented in Russia, China, Turkey, and even the United States by academicsFootnote 13 as well as prominent news outlets.Footnote 14 Further, social media influencers have begun to use political, cultural, and especially religious “cues” to engage and coopt the general public sentiment around important issues and thereby influence conversation and attitudes, a crucial area of research that is understudied in the non-Western world.Footnote 15

This essay is part of a larger research project that explores the manipulation and politicization of the online public sphere in the Gulf, using the case study of the ongoing regional diplomatic crisis, which began in June 2017.Footnote 16 This crisis has increased the politicization of the online public sphere,Footnote 17 making it even more important to better understand both the content and the networks of digital discourse in the region and the influencing of this discourse for political ends. Drawing on qualitative examples – on the role of women, territorial boundaries, and the FIFA World Cup 2022, set to be hosted by Qatar – the essay explores the extent to which social media represents a change in the methods of diplomacy and communication in the Gulf, or simply a new battleground for old rivalries. These findings do not claim to be representative, but rather are meant to provide contextual understanding of observed behavior. Utilizing insights from political science, communication, and digital media studies, the essay suggests that the politicization of the online public sphere in the region has been exacerbated, but not caused, by the current diplomatic crisis.

The Gulf Diplomatic Crisis and the Politicization of the Online Public Sphere

On June 5, 2017, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, and Egypt broke diplomatic relations with Qatar and closed their land, sea, and air borders.Footnote 18 Yet defying initial expectations of Qatar's capitulation, the country proved resilient, leveraging its international support into new opportunities for economic and military partnershipsFootnote 19 and substantive domestic change in policies and entrepreneurship.Footnote 20 The blockade is now seen as a “strategic failure” resulting in a “contest of endurance”Footnote 21 or a “long estrangement,”Footnote 22 rather than subordination or regime change.

In this context of a long-term stalemate between the countries, the online public sphere has become a crucial tool for promotion of political agendas to both internal and external audiences.Footnote 23 Yet some of the most propagated hashtags are eerie echoes of long-standing issues and previous grievances between the countries. Take one example: the rise of derogatory hashtags or other posts referencing Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, the wife of the former Amir of Qatar, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani (r. 1995–2013) and the mother of the current Amir, Sheikh Tamim bin Khalifa Al Thani (r. 2013-present). More than simply the wife and mother of powerful men, Sheikha Moza has exerted great political and cultural weight over the Qatari public sphere since 1995, especially as the Chairperson of the Qatar Foundation, an organization focusing on education, science, and community development, with Education City and its campuses of international and American universities as its flagship projects. She has also been a leader in the domestic reforms of both public education and healthcare, and remains active on an international scale as well, promoting various global education initiatives.

During the current diplomatic crisis, the public prominence of Sheikha Moza has made her both a personal target and a symbol of Qatar's national delinquency as a whole. Misogynistic messages that highlight, implicitly or explicitly, the shame associated with public leadership by women have used hashtags such as ʿyail Moza (the kids of Moza) to refer to the people of Qatar, as well as “Mama Moza” [Figures 1 and 2]. These posts, especially when originating from the UAE, were often supplemented with the hashtag ʿyail Zayed (the kids of Zayed), which was meant to contrast Qatar with the manliness and strong leadership of the former Emirati Emir.

Figure 1: A tweet on politics in Qatar that uses the hashtag “Kids of Moza.” Translation: “#Qatar demands… The answer is in the ground, oh sons of #The_South [Saudis]. Step on anyone who is related to Qatar, no matter what their situation is… […] Life or death, oh #Kids_of_Moza. #The_South is bigger than you.”

Figure 2: A tweet on politics in Qatar that uses the hashtag “Mama Moza.” Translation: “[…] a woman's manipulation and control of Qatar is an ignominy and a disgrace #Mama_Moza.”

Not all of these misogynistic messages found support within the originating countries: The post by the Emirati Hamad Al-Mazrooi, a close associate of the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan (r. 2004-present), which directly attacked Sheikha Moza's honor through a series of tweets in which her image was doctored into various salacious acts and situations [Figure 3], created a backlash not only among Qataris but also among Emiratis and other GCC citizens, who used hashtags like “Sheikha Moza is our source of pride” and “Hamad Al-Mazrooi does not represent us” to express their shock over these attacks. Yet the presence of these hashtags and posts, whether accompanied by support or dismay, sent an overall message that the traditional leadership of the Gulf is patriarchal, and that countries that allow women to serve in positions of power are suspect and weak.

Figure 3: Hamad Al-Mazrooi tweet that directly makes fun of Sheikha Moza. Translation: “I'm dying over your mother, Tamim…”

While these messages are being delivered in new textual and visual ways, the content is old. Although the proper place of women has been fluid throughout the history of the Gulf countries,Footnote 24 the influx of oil wealth in the 1970s enabled regime and society to enforce patriarchal norms on women, a process led by Saudi Arabia.Footnote 25 Yet Qatar's interpretation of the role of women in society, especially since 1995 with the rise of Sheikh Hamad and Sheikha Moza, has challenged more conservative preferences, both within Qatar and in the region. While Qatari women still encounter patriarchal laws and customs in areas such as citizenship laws, workplace discrimination, and divorce and custody,Footnote 26 government rhetoric actively encourages women to contribute to Qatar's socioeconomic growth. While my colleagues and I have connected this rhetoric to Qatar's national development goals of building a diversified knowledge-based economy,Footnote 27 Roberts also attributes this official encouragement to Sheikh Hamad's interest in diversifying his country's security beyond dependence on Saudi Arabia, writing,

Nothing about traditional Saudi Arabian values and policies chimes with Hamad bin Khalifah's world-view or proclivities, and he appears to have had no time for the rigidity that characterises the core of the Saudi state. Nor did he believe that women should play an anonymous, subservient role. … Were Hamad bin Khalifah to have consciously drawn up a range of policies that would cause the most friction with Saudi Arabia, the list would have been likely to have included offering women a prominent place in public discourse.Footnote 28

By promoting female leadership – including giving women the right to vote – Qatar successfully differentiated itself from its more conservative neighbor, but built up tension in the process. With this contentious history in mind, the social media criticism of Sheikha Moza's public role can be understood as but the latest version of the perennial argument about the place of women in Gulf society today.

Another example of rehashing old grievances on a new digital stage concerns the hashtags that refer to Qatar as the bordering Saudi region, “Salwa.” These hashtags, such as jazīra Salwa (Salwa Island) or jazīra Salwa al-sharqiyya (Eastern Salwa Island), imply that Qatar is a territory of Saudi Arabia and question its sovereignty and legitimacy as an independent state. The “Salwa Island” hashtag has been used by prominent figures such as Saud Al Qahtani, a Saudi media consultant and royal court advisor to the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, before his demotion in October 2018 due to the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.Footnote 29 Al Qahtani's original tweet [Figure 4] gained over 3,000 likes and more than 6,000 retweets, and he continued to use the hashtag to respond to news tweets about Qatar and “correct” them to use “Salwa Island” instead of Qatar in their correspondence. Likewise, “Eastern Salwa Island” served much the same purpose, deriding Qatar's territorial sovereignty and bringing attention to the Saudi plan to dig a canal along the Saudi-Qatar border and effectively turn Qatar into an island.Footnote 30Figure 5 depicts a caricature implying that the Muslim Brotherhood (with the oar) and Al Jazeera (with the saw) are the ones responsible for the detachment of Qatar both physically – through its land border – and symbolically, through its severed alliances with Saudi Arabia and its regional neighbors.Footnote 31

Figure 4: Saud Al Qahtani “#Salwa Island” tweet. Translation: “The representative of the eastern part of #Salwa_Island (formerly known as Qatar) in the Arab summit is shunned aside at the extreme right of the picture. All the attendees – presidents, ministers, and visitors – are exchanging friendly talks and brotherly feelings except for him, talking to himself, and between his eyes are the hands of the #Two_Hamads_Organization, stained with the blood of nations. #Servant_Say_Hi_to_Him.”

Figure 5: A tweet referencing the hashtag for “Eastern Salwa Island.” Translation: “Soon… #Eastern_Salwa_Island (formerly known as Qatar), and the #Two_Hamads_Organization can go to hell.”

Ulrichsen, Roberts, Gray, and KamravaFootnote 32 have each written on the historic tensions that have simmered between Qatar and its neighbors over relations with Islamist groups, particularly the Muslim Brotherhood, as well as Al Jazeera's provocative regional coverage. Yet it is also important to remember that border disputes and conflicts over territorial sovereignty have often occurred between Qatar and its neighbors. According to histories of Qatar, Sheikh Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani (r. 1878–1913) spent much of the late 1800s strategizing ways to avoid becoming subsumed by Britain, the Ottoman Empire, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Abu Dhabi.Footnote 33 That he was successful in this endeavor can be attributed in part to his pragmatic politics and in part to the fact that Qatar's territory did not seem to have anything of value to warrant invasion and occupation.

This is no longer the case; Qatar's immense reserves of natural gas, from an offshore field shared with Iran, supply a third of the world's liquefied natural gas needs, making territorial takeover a much more tantalizing opportunity. Qatar has reason to be nervous about its territorial integrity: the shared land border between Qatar and Saudi Arabia has been the site of multiple border skirmishes in 1992, 1993, and 1994, and Saudi Arabia's involvement with the 1996 failed counter-coup against Sheikh Hamad further increased tensions about external meddling in regime change.Footnote 34 Qatar drastically underprices its natural gas exports to its neighbors, especially to the UAE via the Dolphin Pipeline, an action that takes on the flavor of a shakedown when seen in a context of regional tension.Footnote 35 As well, Qatar has had long-standing feuds with its island neighbor to its northwest, Bahrain, over the territorial rights to Al Zubarah, a northern town on the Qatari peninsula. After fifteen years of Saudi mediation, Qatar referred these issues to the International Court of Justice in 1991, which took another ten years to rule in favor of Qatar's sovereignty in Al Zubarah.Footnote 36 Yet during the current diplomatic crisis, Bahrain has made statements about reopening these border issues,Footnote 37 demonstrating that this grievance is still simmering. It is in this historical context that the hashtags referring to Qatar as “Salwa Island” take on an ominous tone, reminiscent of previous territorial conflicts.

Now let us turn to the hashtags and tweets surrounding the 2022 FIFA World Cup, which is set to be hosted by Qatar as the first country in the Middle East to host the prestigious sports mega-event. Do we find the same pattern of new media put to the service of old battles?

Sports and National Legitimacy: The Case of the FIFA World Cup 2022

The link between sports and nationalism has been well argued: take Orwell's classic line that sport is “war minus the shooting.”Footnote 38 In this 1945 essay, Orwell draws special attention to “the nations who work themselves into furies over these absurd contests,” convincing themselves that they are “tests of national virtue.” Likewise, Hobsbawm demonstrates that the 1920s and 1930s saw the rise of sports as symbolic stand-ins for the nation-state as a whole: “an expression of national struggle, and sportsmen representing their nation or state, primary expressions of their imagined communities.”Footnote 39

More recently, Roche's foundational work on the particular nation-building power of “mega-events” has clarified the link between hosting sports events and nationalism.Footnote 40 A country does not have to participate in the sporting competition and win; it merely has to host the event to receive a boost to nationalism. Mega-events, as Roche defines them, are “large-scale cultural (including commercial and sporting events) which have a dramatic character, mass popular appeal, and international significance.”Footnote 41 Besides the Olympics, examples of mega-events also include World Expositions (“Expos”) and – of course – the World Cup, which began in 1930 in the midst of Hobsbawm's charted shift of international sporting events toward nationalist symbolism.

The importance of hosting these mega-events is found in the state's ability to construct and present images of itself on a previously unprecedented scale to both domestic and international audiences. Thus, despite the intense amount of money, time, and effort that must be devoted toward hosting events on this scale, nations seek these opportunities for the associated national, cultural, economic, and political benefits. As Cha argues, sports – whether performed or hosted – is the lens through which states project their image and identity both domestically and internationally.Footnote 42 Cha quotes Olympic athlete Joey Cheek to highlight the intertwined nature of sports and politics: “Countries stage the Games not just because they like sport but because they want to showcase their country, people, culture and political systems. It makes no sense to say it is not political.”Footnote 43 Likewise, Roche argues that mega-events, and especially hosting them, “represent key occasions in which nations could construct and present images of themselves for recognition”Footnote 44 on a previously unprecedented domestic and international scale, and often become “important elements in ‘official’ versions of public culture.”Footnote 45 Building on these ideas, Koch argues that sports mega-events, in particular, offer their hosts “an opportunity to showcase their cities and their countries to the world – an exercise wherein nation-building, place-branding, and urban boosterism all intersect.”Footnote 46

The states of the Gulf – particularly Bahrain, Qatar, and the UAE (Abu Dhabi and Dubai) – have seized recent opportunities to host elite sporting events to “broadcast an image of Gulf cities as ‘cosmopolitan,’ ‘modern,’ and ‘globalised.’”Footnote 47 For example, Qatar hosts roughly 30 elite sports events every year, organized by the Qatar Olympic Committee: 2018 saw top events in sports such as gymnastics, swimming, football, handball, squash, volleyball, track and field, basketball, equestrian, weight lifting, and, incredibly enough, ice hockey.Footnote 48 Qatar's successful bid in 2010 to host the FIFA World Cup in 2022 has followed this regional strategy – spurring specific infrastructure development, broadcasting a cosmopolitan image to the world, and representing a modern and globalized version of the Middle East to an international audience.Footnote 49

But understudied in the extant literature is the recognition of the competitive – often zero-sum – nature of this strategy. Similar to an individual game between two teams, the procurement of hosting rights is itself another form of competition between Gulf countries, with clear winners and losers. Bromber and Krawietz give an example of the scholarship that, by focusing on the rise of the Gulf as a whole as a “modern sports hub,” misses the intra-competition within the Gulf.Footnote 50 The authors’ research combines Bahrain, Qatar, and the UAE into “a telling sample” to argue that “the triplet in question has led the pack” in terms of modern sports hub development in the Gulf, referring to the three countries as “it” rather than “them” for the remainder of their work.Footnote 51 While it is true that Gulf countries have been increasingly visible as the hosts of major sports events, by lumping together these three countries, the resulting analysis obscures the in-fighting and competition that exists between the three.

Let's take a deeper look at the ways in which Qatar's regional neighbors have used news media and social media to convey messages about the upcoming World Cup. Once Qatar won the World Cup bid, the UAE made clear, through both private outreach and public media statements, that the country was willing, even eager, to help share the duties (and privileges) of hosting. For example, a 2013 Arabian Business article [Figure 6] reported that the UAE Football Association was willing to offer its resources and venues to a joint hosting of some World Cup matches.Footnote 52 However, the supportive tone of this article contrasts sharply with the messages after the onset of the regional crisis.

Figure 6: A 2013 article reporting on the UAE's offer to help host the World Cup.Footnote 54

Within days of the start of the crisis in 2017, hashtags began to surface of the UAE taking over the hosting rights for the 2022 World Cup. An image below [Figure 7] shows the first use of the hashtag, “The UAE will host the 2022 World Cup,” written by a Saudi citizen, Hammad Al-Hammad, which conveys the “solution” of giving the World Cup to the UAE. Another example [Figure 8] originates from the Twitter account of Lieutenant General Dhahi Khalfan, the head of security in Dubai, which states that “if the World Cup leaves Qatar, Qatar's crisis would be over.” While some analysts parsed his words to indicate that the UAE's desire to host the World Cup was a catalyst for the siege, Khalfan's full tweet refers to the cost of the World Cup and the possible desire on the part of Qatar to get out of these financial allegations, and he later insisted that his tweet was referring to Qatar's financial crisis, not the diplomatic crisis. Yet the UAE has continued to express its interest in hosting matches for the 2022 World Cup, with a senior Emirati sports official stating that the UAE “would be willing to provide any help needed” if Qatar and FIFA chose to expand the tournament from 32 to 48 teams, necessitating four additional stadiums.Footnote 53

Figure 7: “UAE will host the World Cup” hashtag. Translation: “#UAE_will_host_the_World_Cup_2022 In case the blockade and boycotts of anything supporting Qatari terrorism continue, the UAE can then organize the World Cup and we should all be supportive.”

Figure 8: “Qatar's crisis will be over” tweet. Translation: “If the World Cup leaves Qatar, Qatar's crisis will be over, because the crisis was created to get away from it, as the costs are greater than what the two Hamads’ regime has planned for.”

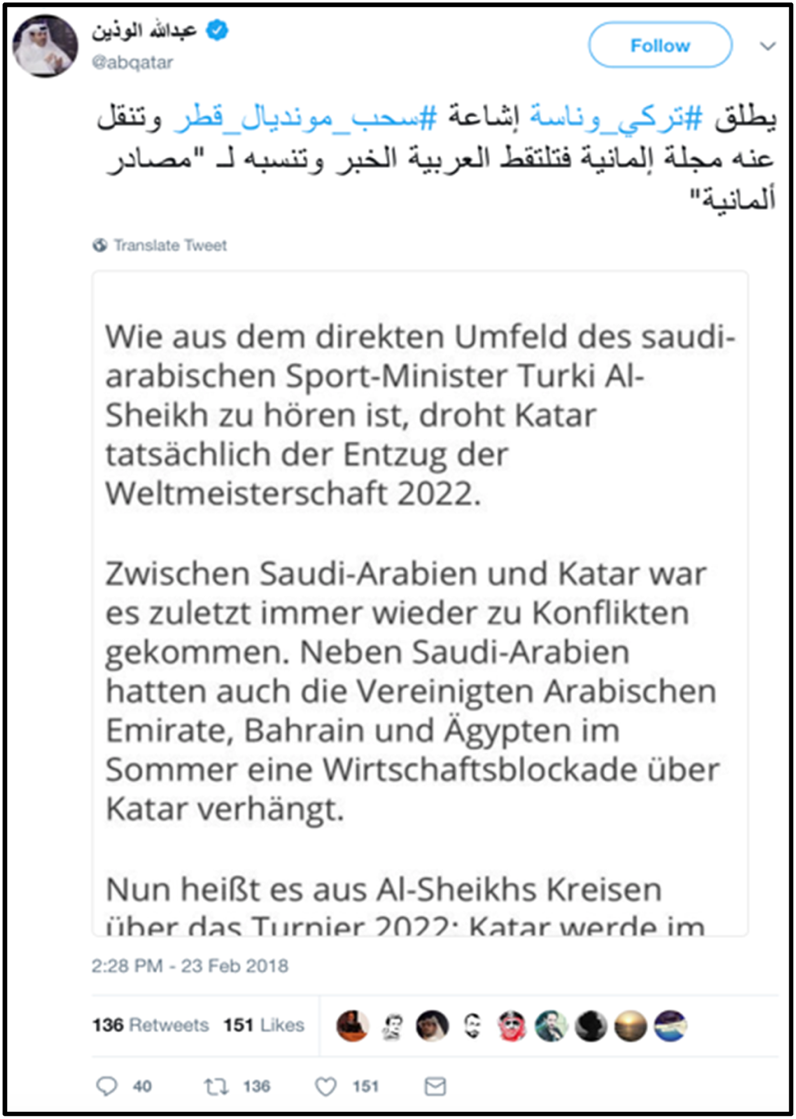

Turning to Saudi Arabia's role in using media to convey messages about the 2022 World Cup, February 2018 saw the use of fabricated news sources to spread the claim that a transfer of the games from Qatar to Great Britain or the United States was imminent. A report by Focus, a German newsmagazine [Figure 9], reported that FIFA was considering moving the games elsewhere because of concerns over vote-rigging.Footnote 55 Various Saudi news sources [Figures 10, 11, and 12], such as Al-Arabiyah and Saudi News, quickly tweeted this article. Yet rebuttals from Qatar-affiliated sources, such as the Al Jazeera France office director, Ayache Derradji and the Qatari writer Abdullah Al-Wathen, noted that Focus’s source was Turki Al-Sheikh, an adviser of the Saudi royal court and the chairman of Saudi Arabia's General Sports Authority. While Al-Sheikh denied being the source of the rumor, this incident depicts an instance of state actors using social media to disseminate fake news and garner re-tweets in support of a particular agenda.

Figure 9: German newsmagazine Focus reporting that Qatar might not host the World Cup, February 23, 2018. Translation: Title: “Qatar is threatened with the withdrawal of the World Cup 2022, USA or England are possible hosts.” In bold: “… According to information from Saudi Arabia, FIFA will announce a decision in late summer of this year.”

Figure 10: A Saudi news source cites the German article claiming that Qatar could lose hosting rights, and a rebuttal from username @AyacheD, affiliated with Al Jazeera France. Translation: @AlArabiya_Brk: “German media sources: [the decision to] give Qatar the 2022 World Cup hosting rights had no integrity #AlArabiyaBreaking” @AyacheD: “[…] it would have been best if you also mention that your blond German source itself said that it is quoting Mister Turki Al-Sheikh…”

Figure 11: A different Saudi news source tweets about the German article. Translation: “A German source confirmed that the 2022 World Cup would be transferred from Qatar to either the UK or the US.”

Figure 12: A Qatari Twitter user describes how the rumor about Qatar losing its hosting rights started. Translation: “#Turki_is_so_much_fun [Turki Al-Sheikh] releases the rumor of #withdrawing_the_2022_World_Cup_from_Qatar and it was reported in a German magazine, where it was then picked up by Al-Arabiya news channel and attributed to ‘German sources.’”

Similar to the historical tensions over gender roles and territorial borders, the hashtag battles over the 2022 World Cup are using new media tools to advance competitive agendas over hosting rights that have existed between the Gulf states since the mid-2000s. The examples presented suggest that the competition to host sports events can be as fierce as actually playing in these sporting events, and the benefits of being the successful bidder may be outweighed by the unintended downsides. These costs may go up as the event becomes bigger: Zirin calls these sports mega-events “neoliberal Trojan horses” and traces their unintended consequences through several case studies, including Greece (2004), Beijing (2008), Vancouver (2010), South Africa (2010), and London (2010),Footnote 56 and Grix notes the “Janus-faced nature of hosting sports megas,” including spiraling security costs in Russia and massive public demonstrations in Brazil.Footnote 57

When it comes to Qatar's successful World Cup bid, the existing literature largely focuses on the positive consequences and elides the domestic and regional tensions that have arisen from stepping onto this stage.Footnote 58 Roberts, for example, focuses on the positive brand publicity: “Securing the right to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup is the crown jewel … and is arguably the single most prominent act that Qatar has undertaken in terms of publicising its brand.”Footnote 59 And despite divided opinions among Qataris on the feasibility, investment, and cultural cost of hosting the World Cup, Roberts argues that “providing sporting infrastructure is a domestically popular move”Footnote 60 and the World Cup “represents the pinnacle of Qatar's sport hosting ambitions.”Footnote 61 While Qatar has received international media criticism of the country's alleged bribes to secure the bid as well as increased scrutiny of labor rights and treatment in the country,Footnote 62 increased regional tensions have been largely overlooked in the literature.

Yet Qatar's leap onto the world stage with its successful bid of the first sports mega-event in the Middle East may have led the country toward an unexpected consequence: heightened rivalry with its neighbors. Academics and media alike have proffered that winning the bid for the FIFA World Cup 2022 was seen as too big of a “win” for Qatar by its rivals in the Gulf, particularly the UAE.Footnote 63 “Expect envy,” wrote financial analyst Heidi Moore in a post-bid analysis of Qatar's success, and envy may indeed be on display in the hashtag battles over the upcoming World Cup.Footnote 64 The stakes of the region's first sports mega-event are high: Qatar will be the new face of the Middle East, supplanting cities such as Dubai. Suggesting that Qatar is already using sports to don the mantle of pan-Arabism, Sheikh Tamim, the Amir of Qatar, specifically called his country's 2019 Asian Cup trophy “an Arab achievement” that “achieved the dream of millions of fans … across the Arab world” (@TamimBinHamad, February 1, 2019). FIFA's May 2019 decision to maintain the 2022 World Cup at 32 teams, shelving the 48-team expansion plan until 2026, further solidifies Qatar's position as the sole host of this mega-event and deals an economic blow to the UAE's Dubai in particular, which would have been a natural choice for hosting events and tourists in an expanded World Cup.Footnote 65 Add this competitive shock to the already existing regional tensions over gender roles and territorial borders, along with relations with Iran and the Muslim Brotherhood, gas production and trade, and Al Jazeera's regional coverage, and Qatar's successful bid for the FIFA World Cup may have been the proverbial straw that broke the camel's back regarding the grievances and rivalries that have led to the diplomatic crisis in the Gulf today.

Conclusion

The research project as a whole, of which this essay is a part, explores the use of digital and social media as a tool of diplomacy and disruption in the Gulf since the start of the diplomatic crisis. Academics are increasingly recognizing the influence of the online public sphere on social and political discourse across the world, and the politicization of digital media in the Gulf region is of particular importance to study. Yet it is important to consider what has changed and what has remained the same as the Gulf regional crisis continues into its third year.

This essay has given some contextual examples of online battles over sociocultural and political issues such as patriarchy, historical legitimacy, and soft power. While these debates are being expressed in new media formats, the underlying issues have long been flash points between the Gulf countries. In particular, this essay's analysis suggests that winning the hosting rights to a sports event may be as important as winning the event itself, and that the competition over Qatar hosting the region's first sports mega-event – the 2022 World Cup – may be playing out online as a proxy for larger tensions over the next new face of the Gulf region and the Middle East as a whole.

There are several avenues for additional research to build upon this analysis, including a quantitative analysis of the social media networks involved in spreading these tweets and hashtags to better understand the origin and diffusion of these ideas as well as to draw generalizable patterns. A comparative content analysis of social media as a persuasive tool would also offer fertile ground for future research. Yet the preliminary findings suggest that these new digital tools are advancing well-trod lines of attack, as old battles are being fought on the new stage of online social media. In this sense, the hashtag conflicts presented here are continuations of long-standing rivalries and grievances in the region. While the stage may have changed, the competition has remained the same.