Introduction

China’s economic development, rapid demographic change and booming urbanisation have led to growing demands for welfare services. The Chinese government has consequently looked for new ways to provide for the people. Emulating welfare models from post-industrial societies, since the mid-1990s it has experimented with contracting of social services to non-governmental actors such as the private sector and social organisations. Footnote 1 In 2013 government contracting was adopted as a national policy with two main strategic aims: to deepen public sector reform, and to strengthen and innovate in social management Footnote 2 (State Council, 2013; CCCP, 2014). These policy aims draw on the theoretical premise that contracting of services improves public sector efficiency, service quality and capacity to meet social need, informed by ideas of New Public Management (NPM) (Dunleavy and Hood, Reference Dunleavy and Hood1994). NPM has emphasised the introduction of market principles such as privatisation, choice, competition, performance evaluation and decentralisation to address public sector inefficiencies. Enacting these principles through services contracting is argued to reap numerous benefits. These include cost reduction (Domberger and Jensen, Reference Domberger and Jensen1997), enhanced quality, risk transfer, accountability (Jensen and Stonecash, Reference Jensen and Stonecash2005), civic participation, governance (Bovaird, Reference Bovaird2007), and partnerships (Brinkerhoff, Reference Brinkerhoff2002). Also beneficial is using the comparative advantage of non-public agents, such as flexibility and responsiveness to community needs (Deakin, Reference Deakin, Alcock, Erskine and May2003). Some of such improvements in cost effectiveness and service quality have been questioned, especially for the sector of social services when compared to technical services (Hart et al., Reference Hart, Shleifer and Vishny1997; Bel et al., Reference Bel, Fageda and Warner2010; Petersen and Hjelmar, Reference Petersen and Hjelmar2014; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Houlberg and Christensen2015). This is due to the differences in service complexity and diversity, with welfare services accounting for high asset specificity and low measurability, which involve higher transaction costs (Petersen and Hjelmar, Reference Petersen and Hjelmar2014). Despite these critical accounts, the aforementioned policy and theoretical narratives advocating for contracting have influenced the emerging academic literature on China’s contracting of services.

This article comprehensively reviews the emerging scholarly research on government contracting of services to social organisations in China to explore three questions: What are the main themes and narratives used to explain contracting of services in China? What evidence is there to prove the claims of these narratives? Does this evidence support the leading policy and theoretical narratives? By narrative we mean a cohesive way of presenting, representing or understanding the topic constructed to give an explanation, justification or emphasis of a perspective, set of ideas, values or ideology. Footnote 3 We conduct a ‘Critical Interpretative Synthesis’ (Dixon-Woods et al., Reference Dixon-Woods, Bonas, Booth, Jones, Miller, Smith, Sutton and Young2006) of the academic literature on China’s contracting, and we identify three distinct emerging narratives: public sector reform, improvement of service quality and capacity, and transformation of state-society relations. We argue that the first two narratives appear generally in the literature, although there is nuanced yet limited empirical evidence to support them. We argue that the maintenance of these two narratives is related to general lack of interrogation of the theoretical and ideological currents underpinning the Chinese government’s policy shift towards contracting, one of them being NPM. In contrast, controversy arises in the analyses of how contracting affects state-society relations, with two sets of arguments: the first suggesting that contracting develops the sector of service-delivery social organisations, while the second argues that contracting is a new form of social control. We find deeper theoretical engagement with issues around state-society relations in the latter narrative, with authors suggesting government contracting reflects the state’s strategies towards civil society such as ‘welfarist incorporation’ (Howell, Reference Howell2015, Reference Howell2019). We identify gaps in research and suggest a future research agenda.

We first provide a synthesis of the methods used. We then identify the three narratives that explain contracting of services. We identify the main gaps in research, which lead us to assess the validity of leading narratives on contracting in China and propose an agenda for future research. We demonstrate how scholars have approached the subject matter and, in some cases, uncovered adverse consequences of contracting, most clearly, for state-society relations. However, we highlight how, to a certain extent, the literature has approached the subject from an empirical perspective and lacked interrogation of theoretical and ideological frameworks informing the adoption of the policy of contracting of services, such as NPM. This has led to the literature generally echoing the government’s policy agenda and seemingly justifying the policy change. This raises several questions beyond the scope of this article, perhaps most importantly the role of scholars in producing knowledge that may or may not support dominant narratives.

Methods

There is significant academic interest in contracting of services in China; yet, it is a novel field. This article is based on a thorough bibliographic review of scholarly research published in the English and Chinese languages. As an established practice, the literature review aims to map the state of the art of a given field of knowledge and identify gaps to develop further research (Tranfield et al., Reference Tranfield, Denyer and Smart2003). We adhere to the principle of the ‘Critical Interpretative Synthesis’ that ‘recognises the interpretative work required to produce an account of disparate forms of evidence’ (Dixon-Woods et al., Reference Dixon-Woods, Bonas, Booth, Jones, Miller, Smith, Sutton and Young2006: 39). On this basis, we devised a research strategy to identify the relevant literature in both languages.

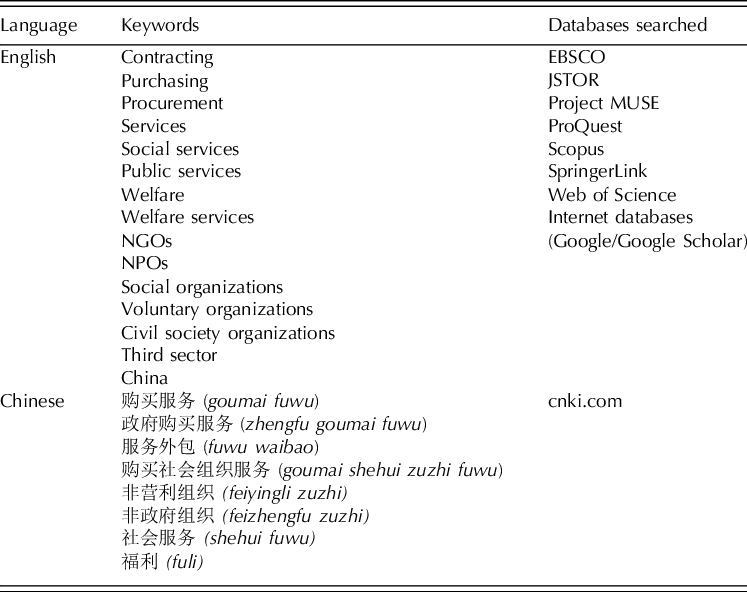

First, given that the use of thesaurus terms has proven to be efficient in conducting literature reviews (Evans, Reference Evans2002), a list of search terms was created in both languages. These terms were used to search literature in electronic academic databases as detailed in Table 1. 2018 was used as a time filter, and later studies are not included in the analysis. Footnote 4 Most research was published after 2010, with a peak of publications appearing after 2013 consistent with the release of major policy (State Council, 2013).

Table 1 Search strategy for literature review

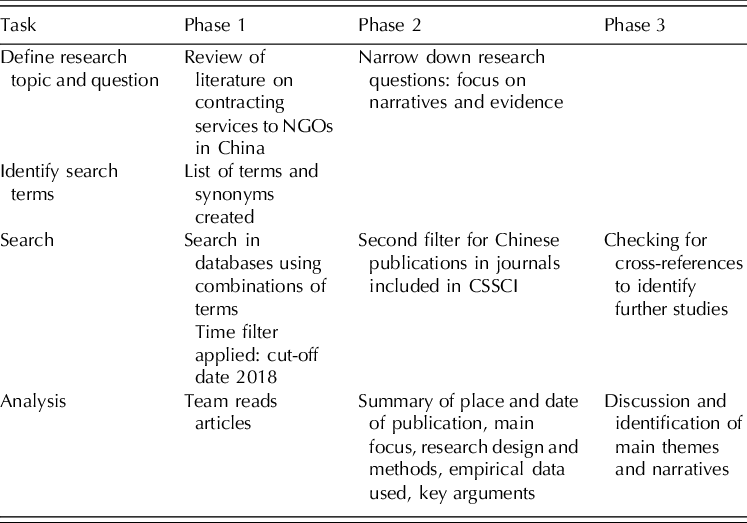

A filter was performed for articles in the Chinese language to select articles published in journals included in the Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI), which indicates high quality and impact of the literature. This filter rendered 658 articles. All articles were briefly read, and those studies most relevant to our research questions were included in the final analysis. Articles that addressed other topics related to NGOs and NGO-state relations in China, but that did not directly speak about contracting, were excluded. Bibliographic references were cross-checked to identify further relevant studies. Table 2 summarises the research strategy.

Table 2 Research protocol for literature review

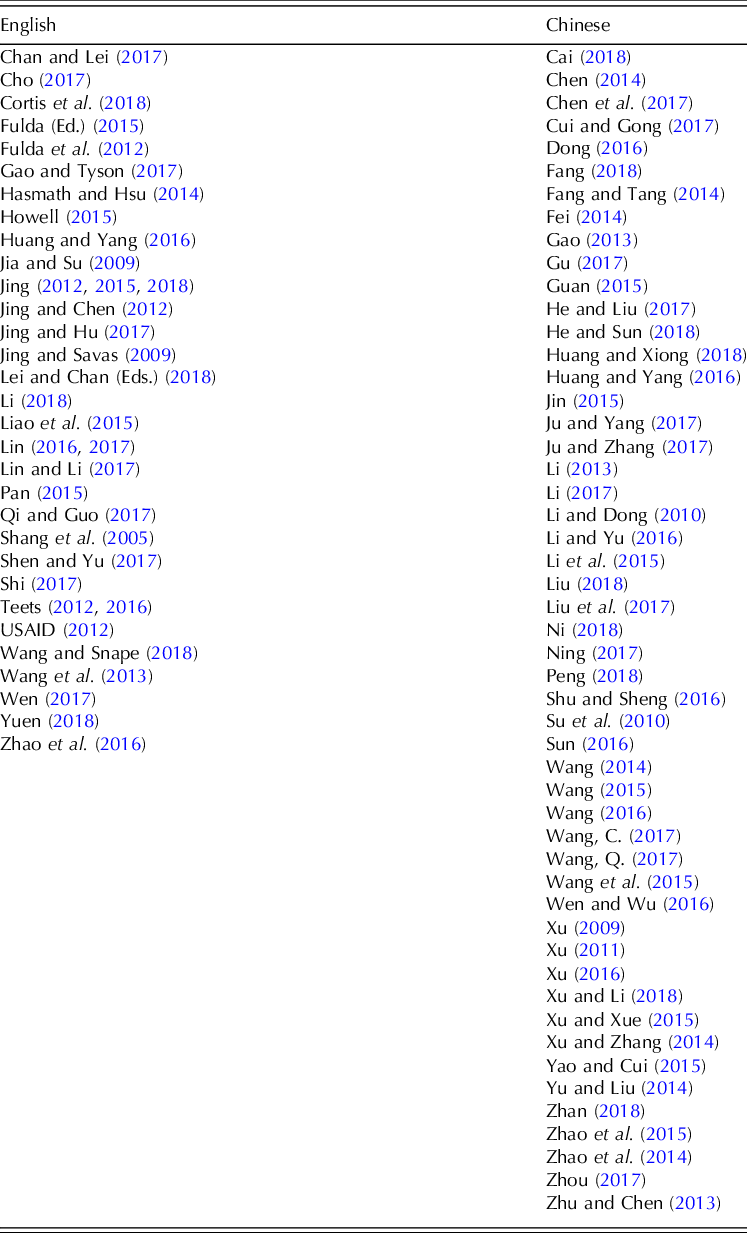

In English, thirty-one academic publications, two policy reports, and two edited books were included in the review. In Chinese, fifty-one academic publications were included in the final analysis. Table 3 provides the full list of studies included in the review.

Table 3 Overview of studies included in the review

Through an inductive and iterative process of reviewing the existing literature, refining the research question, re-reading and discussing the literature amongst the research team, we inferred the mentioned narratives: namely, public sector reform, service capacity and quality, and transformation of state-society relations. Footnote 5

Public sector reform narrative

The Chinese government justifies contracting services to social organisations as a means to deepen public sector reform (State Council, 2013; CCCP, 2014), which was a key aim of New Public Management in the 1980s. The principal justification for these reforms were downsizing of the public sector, efficiency and cost reduction (Hammerschmid et al., Reference Hammerschmid, Van de Walle, Andrews and Mostafa2019). Contracting was one mechanism used to achieve these aims. In China, the rise of contracting has sprouted a body of literature on the topic explaining contracting as the path to public sector reform (Jing, Reference Jing2012; Jing and Chen, Reference Jing and Chen2012; Dong, Reference Dong2016; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wu and Tao2016; Chan and Lei, Reference Chan and Lei2017; Chan, Reference Chan, Lei and Chan2018), mirroring the government’s policy rationalisation, and to a certain extent, the ideas of NPM. This narrative asserted in the literature proposes that contracting will address the inefficiencies of the public sector; introduce competition; and transform government functions. We review each element in turn.

Public sector inefficiency

Public sector reform targets public institutions. Footnote 6 In policy, the government has recognised the role of social organisations in the provision of social services as ‘beneficial for the acceleration of the transformation of government functions, innovation of public service delivery modes, increasing the efficiency and quality of the provision of public service’ (MoCA and MoF, 2014, emphasis added). This is explicitly achieved through applying the principles of the market economy, as the Communist Party of China (CPC) decided to ‘promote market-oriented reform in width and in depth, greatly reducing the government’s role in the direct allocation of resources, and promote resources allocation according to market rules, market prices and market competition, so as to maximize the benefits and optimize the efficiency’ (CCCP, 2014: Chapter 1, Section 3, emphasis added). Both policy and the emerging scholarly literature build on the premise that contracting addresses the said inefficiencies of the public sector and the consequent lack of quality of services (Chan, Reference Chan, Lei and Chan2018).

In the literature we encounter the assertion that, due to overly bureaucratic and burgeoning size, public institutions displayed numerous inefficiencies and an inability to adapt to changing interests and needs. As Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Wu and Tao2016: 2231) stated, the public unit was not ‘cost-efficient (n)or able to meet increasing service needs’. This narrative is put forward by authors (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wu and Tao2016; Chan and Lei, Reference Chan and Lei2017; Qi and Guo, Reference Qi and Guo2017; Shi, Reference Shi2017; Wen, Reference Wen2017; Jing, Reference Jing2018; Ke, Reference Ke, Lei and Chan2018) without the necessary evidence to confirm that, in fact, during state socialism or even after the introduction of market reforms in 1978, public institutions were inefficient, and in what ways they were so. The most common assertion is that public institutions were populated by unmotivated civil servants lacking incentives, rendering the public welfare system inefficient (Chan and Lei, Reference Chan and Lei2017). Apart from these claims, there is a surprising absence of evidence of how the public sector was inefficient and more importantly, of how contracting has made it more efficient. Also missing from the literature is a consideration of if and how contracting changes the ownership structure of services that would lead to increased efficiency, an otherwise well-established discussion in the literature (Petersen and Hjelmar, Reference Petersen and Hjelmar2014). This is a relevant question given the Party-state-control over the market economy.

Meanwhile, a few studies have illustrated the benefits of public institutions as service suppliers compared to for-profit and non-for-profit non-state actors. These authors argue that, given their close and relatively equal relationships with government and structural similarity (Dong, Reference Dong2016), public institutions were more stable, capable and better equipped to ensure equality and justice in welfare provision (Ning, Reference Ning2017). These claims, in conjunction with the lack of empirical evidence, puts the narrative that contracting transforms the public sector into question.

Competition

Contracting, in theory, improves public sector efficiency by introducing market principles such as competition (Dunleavy and Hood, Reference Dunleavy and Hood1994). This is also a stated policy aim in China (NPC, 2011: Chapter 8; CCCP, 2014: Chapter 9, Section 15). The emerging literature asserts that the introduction of competition with non-state actors provided a way of pushing state reform (Wang, Reference Wang2015; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Dong and Kong2017). Empirical evidence has shown how local governments pursue competitive practices in a variety of ways. Research has yielded descriptions of contracting arrangements such as competitive bidding and venture philanthropy (Li and Lin, Reference Li, Lin, Lei and Chan2018); oriented purchasing and open-for-application purchasing (Ke, Reference Ke, Lei and Chan2018); position or project contracting (Fang and Tang, Reference Fang and Tang2014; Sun, Reference Sun2016; Cho, Reference Cho2017; Wen, Reference Wen2017; Cortis et al., Reference Cortis, Fang and Dou2018; Li and Lin, Reference Li, Lin, Lei and Chan2018); and the hub system (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wu and Tao2016; Shi, Reference Shi2017). This evidence indicates that contracting is practised through a mixture of non-competitive and competitive arrangements.

Competition in practice has been found to be symbolic at best. Pre-established connections with the government are a well-known pre-requisite to participate in contracting. Research has found that higher-level governments pressure lower-level governments to adopt competitive contracting, but lower-level governments maintain informal contracting practices with organisations with which they have close connections (Jing, Reference Jing2012; Jing and Chen, Reference Jing and Chen2012; Guan, Reference Guan2015). Chan (Reference Chan, Lei and Chan2018) argues that China cannot yet reap the benefits of contracting because it does not have a developed sector of service-delivery social organisations to compete in the market. Moreover, contracting has exacerbated inequalities in the distribution of resources among social organisations (Cortis et al., Reference Cortis, Fang and Dou2018), demonstrating that the market is not a level playing field. This literature review suggests that the competitive feature of contracting has not been fully demonstrated at the local level; on the contrary, local governments maintained informal contracting practices to the detriment of competitive contracting. Therefore, empirical evidence confirms that competition does not yet characterise contracting in China. This challenges the theoretical premise that contracting improves the efficiency of government’s service provision.

The literature also refers to the premise that marketisation was the necessary and best way to address the claimed inefficiencies of public institutions. In fact, to the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of studies showing that contracting has enabled cost reduction, and most importantly, that has considered the transaction costs derived from contracting. Only a handful of studies have drawn attention to concerns around the transactional costs involved in stimulating an underdeveloped NGO sector (Chen, Reference Chen2014; Li and Yu, Reference Li and Yu2016), or increased costs in contracting via hub organisations when compared with direct contracting (Li and Yu, Reference Li and Yu2016). Moreover, the claims of enhanced efficiency have not taken into account the government’s lack of requisite skills and new managerial tasks that have to be acquired (Jing and Savas, Reference Jing and Savas2009; Ju and Zhang, Reference Ju and Zhang2017). To the best of our knowledge, no research has addressed the issue of the proven adverse effects of cost savings on service quality (Hart et al., Reference Hart, Shleifer and Vishny1997: 1129). These issues should be tackled in future research. Thus, narratives redolent in the literature have not questioned the premise of the necessity and direction of the reform, which we suggest derives from the penetration of the ideas of NPM.

Reforming government functions

At the 18th Party Congress the CPC acknowledged contracting as part of the strategic aim to transform government functions (CCCP, 2014: Chapter 9), as it ‘accelerates the construction of a service-oriented government’ (State Council, 2013). Similarly, authors argue that contracting redefines the core functions of the government, transferring non-essential ones to social actors, thus creating a ‘leaner’ government (Liu, Reference Liu2018). Scholars argue that contracting transforms government’s role from direct provider to regulator (Lin, Reference Lin2017). In this scenario the government retains roles such as boundary-setting, determining contracting forms and procedures, monitoring and evaluation (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liu and Li2015; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Dong and Kong2017).

Contracting is expected to reduce the functions and responsibilities of the public sector. However, contracting requires new roles for the government, such as contract management, audit capabilities, and numerous other skills (Van Slyke, Reference Van Slyke2003). Jing and Savas (Reference Jing and Savas2009) identified four generic capacities governments need to effectively deliver services collaboratively with either the private sector or civil society: contract management, market/civil society empowerment, social balancing, and legitimisation. They found that governments in China lacked all four categories. Local governments not only lacked the skills, staff and experience to deliver services, but also the necessary skills to design, implement and manage contracting (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wu and Tao2016; Wen, Reference Wen2017). This suggests that contracting, in fact, has created additional functions for governments, and defies the narrative that contracting has improved public sector capacity and efficiency. If these new functions and risks were taken into account in future research, a more valid assessment of the effects of contracting on public sector efficiency would be produced.

In theory, one benefit for government is that transferring roles to the non-public sector also transfers risks (Lipsky and Smith, Reference Lipsky and Smith1989). However, this transfer of statutory responsibilities is itself not void of risks. For example, the government may face a legitimacy challenge because of having to reconcile two conflicting mandates: to develop the market economy through deregulation, decentralisation, and diversification, and maintain the political regime (Jing and Savas, Reference Jing and Savas2009). There is an absence of research on the concrete risks involved in contracting (Cortis et al., Reference Cortis, Fang and Dou2018). Future research on this issue would contribute to assessing the narrative that contracting transforms the public sector and improves its efficiency.

Service capacity and quality narrative

The second narrative reflected in the literature relates to how services contracting improves the capacity and quality of public service provision. The Chinese government’s policy aim is to improve state capacity (State Council, 2013; CCCP, 2014), strengthen the public service system and create a service-oriented government (State Council, 2013) through market principles (NPC, 2011: Chapter 8; CCCP, 2014: Chapter 9, Section 15). In theory, the competition introduced by contracting enables diversification of service providers, broadening of customer choice, and higher citizen/client satisfaction. The comparative advantages of non-profit and social organisations reside in their flexibility, innovativeness (Deakin, Reference Deakin, Alcock, Erskine and May2003) and responsiveness to community needs (Fowler, Reference Fowler1988). This makes them better placed to personalise provision (Salamon, Reference Salamon1995). In the academic literature, scholars argue that contracting ‘revitalize[s] social services’ (Lei and Cai, Reference Lei, Cai, Lei and Chan2018: 150), or is even ‘China’s social welfare revolution’ (ibid: 157). It is also argued that the government’s adoption of contracting results from the lack of state capacity and expertise to deliver services to an increasingly diverse population with more complex demands (Teets, Reference Teets2012; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Eggleston, Yu and Zhang2013; Chen, Reference Chen2014). In the following we deconstruct the main elements of this narrative and the empirical evidence on how contracting meets social need, affects the diversification of service providers, and improves service quality.

Social need

Social organisations are recognised in Chinese policy as a key player in service provision, given their ‘positive role (…) in discovering new public service demand and promoting supply-demand convergence’ (MoCA, 2016). In theory there is general agreement that not-for-profit are better positioned to identify and target social need (Salamon, Reference Salamon1995), and that contracting allows for the expansion of welfare services (Lipsky and Smith, Reference Lipsky and Smith1989). The emerging literature mirrors the arguments that contracting enables addressing unmet social need. It suggests that the welfare system inherited from the socialist period was unable to meet social need, and that its dismantling after 1978 created a gap in welfare provision. Rapid economic growth, urbanisation, and changes in the social structure sprouted new welfare needs and interests. Demographically, a large aging population, the one-child family structure, and labour shortages put severe pressure on the welfare system and local governments were not able to provide relevant services (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wu and Tao2016; Cortis et al., Reference Cortis, Fang and Dou2018). Hence, contracting was introduced as an innovative solution to meet these old and new types of needs.

It is claimed that contracting allows for the pluralisation of supply, enhancing customer choice and citizen engagement (Jing, Reference Jing2012). It creates a multiple participation structure in which provision can be extended and improved (Chen, Reference Chen2014) given that social organisations can better identify the demands of citizens (Cai, Reference Cai2018) and reach high-risk populations. Scholars have therefore celebrated contracting because, in theory, it better meets social need. However, there is an overwhelming absence of empirical evidence that proves that this social need is now met as a consequence of contracting. Shang et al. (Reference Shang, Wu and Wu2005), who analyse how non-profits address the needs of vulnerable children, are among the few exceptions, together with Teets (Reference Teets2012), who demonstrates some changes in the demographic data on ageing which implicitly suggests an increase in service demand.

Surprisingly too, questions around how social need is defined, assessed, and translated into services are absent from published research. This empirical gap undermines the narrative that contracting expands service capacity and meets social need. There is also a lack of consideration of how the complexity and diversity of social needs drive the high asset specificity of the service sector, which in turn determines its high transaction costs (Petersen and Hjelmar, Reference Petersen and Hjelmar2014: 6). Additionally, the fact that there is hardly any research on the impact on service users confirms that researchers derive that need is being met from the finding of diversification of providers. This, however, does not directly imply that need is covered. A top research priority therefore is to interrogate how need is defined by services users in contrast to the service provided by contracted social organisations.

Service capacity

As mentioned above, contracting is adopted because government lacks capacity to deliver quality services. In China, researchers have argued that contracting has expanded government capacity by cultivating the social work profession and a market of service providers (Chan and Lei, Reference Chan and Lei2017; Wen, Reference Wen2017; Cortis et al., Reference Cortis, Fang and Dou2018). Some authors even claim that social work entirely derives from contracting (Wang, Reference Wang2014), given that ‘more than 90 per cent of total funding of most social work agencies’ (Lin, Reference Lin2017: 1614) comes from contracting. However, some authors have shown that contracted social workers are situated in a marginalised, instrumentalised position (Wang, Reference Wang2014), having to take on administrative work even though this affects service delivery (Zhu and Chen, Reference Zhu and Chen2013; Sun, Reference Sun2016; Wen and Wu, Reference Wen and Wu2016) or diverts them from rights-based activities (Huang and Xiong, Reference Huang and Xiong2018). Cho (Reference Cho2017) found that contracting creates precarious labour conditions and reproduces social inequalities, as it prioritises market principles of efficiency over social work principles of social inclusion and alleviation. Service capacity therefore might be related to quantity of services provided instead of quality.

Contracting has stimulated the proliferation of service-delivery social organisations; however, authors have found that contracting poses significant challenges for their operations and capacity: social organisations may lack the professional expertise and necessary staff to deliver specialised services (Ke, Reference Ke, Lei and Chan2018) and the managerial capacities necessary to engage in services contracting (Wen, Reference Wen2017). They also face several financial constraints that affect the sustainability of their provision, such as detrimental payment arrangements or limitations in the use of contracting funds (Li, Reference Li, Lei and Chan2018). This undermines the stability, capacity and development of social organisations (Ni, Reference Ni2018), making them reliant on maintaining the flow of government funding. This evidence challenges the narrative that contracting improves service capacity. If labour conditions and the challenges faced by social workers and social organisations were taken into account in future research, the claimed improvements in service capacity and quality could be reassessed.

Service quality

In theory, contracting enhances the quality of services (Domberger and Jensen, Reference Domberger and Jensen1997; Jensen and Stonecash, Reference Jensen and Stonecash2005). In China, authors implicitly adopt this narrative (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Yan and Xu2014; Jing, Reference Jing2018), yet, as elsewhere (Petersen and Hjelmar, Reference Petersen and Hjelmar2014; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Hjelmar and Vranbaek2018), there is limited primary evidence to support it. On the contrary, the empirical evidence questions the quality improvements derived from contracting. For example, Wang (Reference Wang2016) found that service users were not satisfied with the services delivered via contracting; and Zhu and Chen (Reference Zhu and Chen2013) found that complaints were made about social workers and doubts expressed on their professionalism. This limited empirical evidence suggests that the narrative that contracting improves service quality is yet to be proven.

Moreover, the literature suggests that contracting lacks valid and standardised monitoring and evaluation measurements (M&E), with quantitative measurements predominating and with a focus on cost efficiency (Jing, Reference Jing2012; Ke, Reference Ke, Lei and Chan2018; Wang and Snape, Reference Wang and Snape2018), instead of service quality. This lack of evidence calls for comparative research of service delivery through contracting and government direct provision, whether contemporarily, or during state socialism. The only exceptions found in the literature are implicit comparative work such as that done by Lin (Reference Lin2017) on community services pre- and post-contracting.

There are various reasons for this gap in research, such as the actual lack of official data to compare service provision before and after contracting, inconsistent M&E criteria, a general lack of assessments of service quality (let along including service users), or the fact that many purchased services are actually new. Indeed, if no service was provided prior to contracting because there was no need for it, it would defeat the causal claim that service efficiency and quality have improved as a result of contracting, although it would support the claim that new needs are being addressed. Surprisingly, very few researchers have attempted to address this absence of evaluation data, rendering it difficult to uphold the claim that contracting improves service quality. This mirrors shortcomings found in international research related to a scarcity of generalisable data and insufficient methodological designs to prove that contracting improves cost effectiveness or enhances the quality of welfare services (Petersen and Hjelmar, Reference Petersen and Hjelmar2014). We argue that the service quality element of this narrative has largely been based on improvements in the supply structure through diversification of service providers and contracting, rather than the demand side.

In sum, there is empirical confirmation that contracting has diversified the supply structure of the Chinese welfare system, with the development of the social work profession and the proliferation of service provider social organisations. Chan and Lei (Reference Chan and Lei2017: 1345) assert that contracting ‘has become [China’s] main welfare strategy’. Yet, there is no concrete empirical evidence of the prevalence of contracting compared to other forms of government service provision, nor of how contracting has really expanded welfare service capacity. Moreover, the enhanced capacity of social organisations and social workers to meet social need and provide high-quality services remains to be demonstrated. By and large, there is lack of empirical evidence that supports the narrative that contracting improves service quality. We conclude that these narratives persist in the literature due to a lack of interrogation of the theoretical premises of contracting of services, such as NPM, which have informed the design and implementation of the policy at the start. Future research could investigate the variety of theoretical frameworks that have informed, penetrated and even dominated policy and academic debates around contracting of services in China.

Transforming state-society relations narrative

In policy, contracting is considered a governance strategy aimed at separating the government and society (CCCP, 2014: Chapter 13) and improving the government’s management of social organisations. In the wider literature, it is argued that social organisations play an increasing role in public service delivery, changing their relationship to the state (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Kenny and Turner2000). In fact, contracting has been claimed as ‘the most important and most radical change to state–society relations since the advent of the modern welfare state’ (Considine, Reference Considine2003: 63). Both in theory and in policy, therefore, contracting of services is considered a transformation of state-society relations.

This narrative is clearly discussed in the scholarly literature on contracting in China. However, two distinct accounts are developed: first, some authors hold that contracting inspires the development of a market of service-oriented social organisations, with effects such as standardisation, professionalisation, expertise and service capacity; conversely, some authors argue that contracting extends government’s control over social organisations, with adverse effects on organisations’ governance, independence, staffing, and advocacy. We review both sides of this debate.

Stimulating the expansion of social agents

Contracting has been seen to create an opportunity for the separation of purchaser and provider and the consequent emergence and proliferation of civic actors that compete in the market to deliver services (Bovaird, Reference Bovaird2007). As mentioned above, scholars view the expansion of non-governmental service providers (Jing and Savas, Reference Jing and Savas2009) as a benefit of contracting, as it develops service capacity (Cortis et al., Reference Cortis, Fang and Dou2018). Some scholars argue that social organisations were undeveloped, with weak institutional structures and lack of credibility (Liao et al., Reference Liao, Zeng and Zhang2015). Contracting supports social organisations in various ways such as through access to policymaking (Shen and Yu, Reference Shen and Yu2017), and to funding, reputation and branding (Jing, Reference Jing2018). Contracting has therefore afforded significant benefits to organisations that stimulate their development.

Contracting has also given rise to other social agents. Research has provided detail on hub organisations and third-party evaluation agencies. Among others, CPC-affiliated or government-organised non-governmental organisations (GONGOs) such as the Disabled People’s Federation (Ke, Reference Ke, Lei and Chan2018) or community service centres (Shi, Reference Shi2017) have been identified as functioning as hub organisations (shunju zuzhi). Hubs manage, supervise and evaluate the contracting process on behalf of the government. Hub organisations, however, can also bid for service contracts, competing with social organisations. This suggests that the market is not a level playing field, and that in China as elsewhere, economies of scale have been given priority (Bovaird, Reference Bovaird2014).

Hubs have constituted one of the most common contracting arrangements in China, and perhaps unique to China. It has been argued that the government uses the hubs to reform the management of social organisations (Yu and Liu, Reference Yu and Liu2014) on the one hand, and incubate the development of social organisations (Xu and Zhang, Reference Xu and Zhang2014; Shi, Reference Shi2017; Ke, Reference Ke, Lei and Chan2018) and provide a bridge with government (Fang, Reference Fang2018), on the other. Scholars seem to accept the newness of hub organisations, whereas the fact these organisations are mainly GONGOs could be interpreted rather as an expansion of existing institutional structures instead of an innovation. Only a few studies have recognised hub organisations’ dependency on government and their bureaucratic pattern as weaknesses (Xu and Zhang, Reference Xu and Zhang2014). There is therefore scope to further interrogate if and how hub organisations transform state-society relations. There is also little evidence to show how the hub arrangement improves service capacity and efficiency (especially if considering transaction costs).

Third-party evaluation agencies are another type of non-public actor that derives from contracting. They are considered crucial in monitoring performance and ensuring accountability, substituting government’s lack of monitoring capacity. They also support the development of social organisations (Cui and Gong, Reference Cui and Gong2017). In theory, their value resides in ensuring transparency and accountability of service provision. Hence, professionalism and independence of evaluators are crucial (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Xu and Yang2015). Both characteristics, however, have been questioned because of their lack of standardised evaluation criteria and procedures, neglect of service users’ perspectives (Jin, Reference Jin2015), and an over-emphasis on quantitative M&E criteria (Yao and Cui, Reference Yao and Cui2015). Evaluation agencies should include independent experts, professional companies, social representatives, and ordinary citizens (Xu, Reference Xu2011). However, only experts from academia (universities, research institutions, and CPC schools), the government and experienced service providers are commonly involved (Gu, Reference Gu2017).

Thus, evidence in the literature supports the narrative that contracting has driven the development of social organisations and new social agents. Some authors see these developments as mutually beneficial for government and social organisations, and as steppingstones towards collaborative governance (Jing and Hu, Reference Jing and Hu2017). However, even with new types of service providers sprouting, evidence of their interdependence with government raises the question whether contracting has transformed state-society relations. In fact, a number of authors assert that contracting has tightened government control over social organisations, reproducing or extending pre-existing state-society dynamics.

Social control

There are critical views of the effects of contracting on state-society relations asserted in the literature. Some authors contest the mainstream theoretical narrative that contracting develops social sector organisations and partnerships (Brinkerhoff, Reference Brinkerhoff2002). For example, Howell (Reference Howell2019: 78) relates contracting in China to the state’s strategy of ‘welfarist incorporation’ by which service-oriented organisations are used ‘instrumentally for welfare and stability purposes’. She argues that contracting allows for service-oriented organisations and simultaneously clamps down on rights-based organisations (Howell, Reference Howell2015, Reference Howell2019). Equally, Zhao and others (Reference Zhao, Wu and Tao2016: 2246) suggest the Chinese government is ‘actively encouraging NPO’s service provision role and suppressing the civil society role through the services contracting process’. Therefore, contracting is seen to be deliberately used to control civic organisations (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zheng and Jia2017).

‘Welfarist incorporation’ first occurs as the government defines the range of services that can be contracted. Studies suggest that contracting focuses on community services rather than public services such as health and education, and on urban citizens rather than on vulnerable people like migrant workers (Li et al., Reference Li, Jin and Wu2015). Consequently, this delimits which organisations can partake in service delivery, and are more likely to be GONGOs (Guan, Reference Guan2015), formally registered organisations and social work agencies with qualified social workers (Xu and Li, Reference Xu and Li2018). Excluded are not only organisations working outside the designated service areas, but also rights-based organisations that address needs of marginal groups (Howell, Reference Howell2015). This process of exclusion challenges the mainstream claim that contracting facilitates partnerships and civic participation.

Second, government incorporates organisations through contracting using strict, regular monitoring, or increased administrative work (Wen, Reference Wen2017; Xu and Li, Reference Xu and Li2018). Also, government controls social organisations more directly through resource dependency (Jing and Savas, Reference Jing and Savas2009). He and Liu (Reference He and Liu2017) showed that because of government’s control of all resources and contracting authority, social organisations rarely challenge the government and enter a bureaucratic relation, becoming ‘foot-soldiers’ of local governments (Zhu and Chen, Reference Zhu and Chen2013; Huang and Xiong, Reference Huang and Xiong2018). The incorporation of social organisations into welfare provision poses challenges to their autonomy, being co-opted ‘into taking responsibility for meeting welfare targets over which they have scant influence’ (Shi, Reference Shi2017: 475). Moreover, organisations have little autonomy or legal protection over their contractual rights (Chan and Lei, Reference Chan and Lei2017), risking sacrificing rights-based agendas to meet governments’ political preferences (Cortis et al., Reference Cortis, Fang and Dou2018). Contracting therefore poses potential risks of mission drift as organisations prioritise the goals of the government, rather than those of users (Wang, Reference Wang2015).

The literature review also suggests that contracting has not necessarily brought about the revolutionary changes to China’s welfare model as was claimed (Chan, Reference Chan, Lei and Chan2018; Lei and Cai, Reference Lei, Cai, Lei and Chan2018), and as observed elsewhere (Considine, Reference Considine2003), at least regarding its restructuring of state-society relations. Empirical evidence presented here provides the most critical view in scholarly work of services contracting, challenging established narratives that contracting separates state and society, enhances partnerships (Brinkerhoff, Reference Brinkerhoff2002) and civic engagement (Bovaird, Reference Bovaird2007). Some research suggests that contracting is an extension of pre-existing modes of social control. In fact, contracting has introduced new and sophisticated mechanisms through which the state exercises power over social organisations, which are characteristic of neoliberalism. Very few authors have framed contracting as part of a broader ideological change in the Communist Party-state, whereas in the international literature there is some acceptance that ideology is a key driver in contracting of social services (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Houlberg and Christensen2015). In the literature on China’s contracting, there is scarce research that questions the ideological underpinnings of government contracting and that systematically interrogates the ideological changes in Party-state discourse regarding welfare provision (Teets, Reference Teets2012; Cho, Reference Cho2017; Chan, Reference Chan, Lei and Chan2018; Lei and Cai, Reference Lei, Cai, Lei and Chan2018; Howell, Reference Howell2019). Chan (Reference Chan, Lei and Chan2018) and Lei and Cai (Reference Lei, Cai, Lei and Chan2018) recognise there is a ‘new ideology’ behind this welfare model, cautiously suggesting linkages with neoliberal drivers.

Only Cho (Reference Cho2017) and Teets (Reference Teets2012) have identified a neoliberal ideological underpinning to government contracting. Cho (Reference Cho2017) argues that government contracting of services is part of China’s neoliberalisation project to ‘re-establish the conditions for capital accumulation and to restore the power of economic elites’ (Harvey, Reference Harvey2005: 19; cited in Cho, Reference Cho2017: 271). Furthermore, the general take on contracting has been from the ‘developmentalist and modernist approaches that overshadow criticisms about retrenchment and privatization of welfare functions’ (ibid: 273). Teets (Reference Teets2012) similarly argues that neoliberal reforms in China reduced the state’s role in the economy and in welfare. The positive aspect, she argues, is a more pluralistic political environment in which social organisations would deliver social services and participate in policy processes. A significant gap in research, therefore, is a systematic study of ideological drivers, rationales, or ‘state intentions’ (Lei and Cai, Reference Lei, Cai, Lei and Chan2018: 158) for contracting. This would allow for reflection on the future direction of welfare and public sector reform, on the penetration of theoretical frameworks and ideologies in Chinese social policy and academic circles.

Conclusion

This review of literature in Chinese and English languages on contracting social services to social organisations in China up to 2018 has identified three main narratives: public sector reform, improvement of service quality and capacity, and transformation of state-society relations. It contrasted the said narratives with empirical evidence available up until 2018. We demonstrated the prevalence of narratives that contracting improves public sector efficiency, capacity and quality of services, despite the absence of or contradictory empirical evidence to support this. Given these claims, it appears as if services contracting has achieved irrefutable successes, which makes the marketisation of welfare services seem a necessary, inevitable and rational direction for China’s welfare system reforms. There is nevertheless controversy among scholars who view contracting as a transformation of state-society relations: some scholars argue that contracting develops the sector of service-delivery social organisations, to the point of even building state-nonprofit relationships towards collaborative governance (Jing and Hu, Reference Jing and Hu2017); while others argue it extends the mechanisms of state control over social organizations in a strategy of ‘welfarist incorporation’ (Howell, Reference Howell2015, Reference Howell2019).

We have demonstrated that the causal relation between contracting and improved welfare services has not been empirically proven. This is due to two reasons: first, lack of data on service quality, given the paucity of systematic M&E practices, and of evaluations that look beyond quantitative measurements of service provision and that include service users; second, a lack of empirical-based research on the impact of contracting on service quality. This is in line with international research on contracting, which has been characterised by similar methodological and data limitations (Petersen and Hjelmar, Reference Petersen and Hjelmar2014). This is due to the characteristics of welfare services, which have been proven to be of low measurability when compared to technical services (Petersen and Hjelmar, Reference Petersen and Hjelmar2014). Moreover, as argued by Cortis et al. (Reference Cortis, Fang and Dou2018) the risks (both economic and political) associated with the introduction of market principles into service-delivery, and transfer of responsibility to social organisations have not been examined in the academic literature. We argue that there are missing narratives in the literature, such as those interrogating and discussing the variety of theoretical and ideological underpinnings of the policy shift, such as the ideas of NPM. Given the proven decisive role that ideology plays in driving contracting of welfare services elsewhere (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Houlberg and Christensen2015), we suggest that the literature on contracting services to social organisations would be enriched by future analyses of the theoretical and ideological changes signified by contracting. As a starting-point we need to investigate how neoliberalism or NPM entered Chinese policy agenda (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Dong and Painter2008; Urio, Reference Urio2012) and scholarly analysis, and why and how these narratives are sustained.

Furthermore, we found that the academic literature reinforces the government’s policy agenda of using contracting to deepen public sector reform and strengthen its management of social organisations. Even when contrasting empirical evidence has been produced, for example, showing inefficiencies in contracting, the literature has tended to explain these as technical problems and offer solutions to improve the practice in China. We argue that scholarly research has therefore contributed to building mainstream narratives around contracting to social organisations to develop China’s welfare system. Authors have raised critical views on the implementation and outcomes of contracting, but have generally not questioned the necessity and the direction of welfare system reform through contracting. This has clearly shaped the nature of debate around welfare and social policy in China. This raises questions about the role academic knowledge can play in reinforcing or challenging mainstream theoretical and policy narratives, a topic that future research should very carefully consider.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the funding provided by the Economic and Social Research Council (UK) Research Grant ES/P001726/1.