Institutionalization

In Portugal, the issue of institutionalization is not recent, since in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries there were already a large number of abandoned children. In 1911 the Childhood and Youth Law was formalized by the State, where interventions of Private Social Solidarity Institutions and Foster Homes were foreseen. The institutionalization is one of the measures to promote the rights and protection of children and youths at risk contemplated in Portuguese legislation (art.º 49, Lei [Law] n.º 23/2017).

According to the 2018 report of annual characterization of institutional care of children and young people, issued by the Portuguese care system, 7,032 children and youths were in a foster care situation, 6,118 (87%) in Residential Facilities for Children and Youth, with adolescents (12–17 years) representing the highest percentage (55%) (Instituto de Segurança Social [Institute of Social Security], 2019). As adolescence is a stage of transition where youths experience various developmental tasks and challenges, the 2015 CASA report already reinforced "the need for an increasingly differentiated intervention on the part of the host, based on therapeutic intervention models" with these youths (Instituto de Segurança Social [Institute of Social Security], 2016, p. 21). Concerning the situation of danger/risk that led to the institutionalization, negligence is responsible for 71.6% of the cases, including reasons like the lack of family supervision, in which the child is left home alone or with siblings, also minors, for long periods of time (58% of situations), followed by deviant parental models (30.4%), and neglect of education and health care (32% and 29%) (Instituto de Segurança Social, 2019).

In some youths, the process of institutionalization has shown to have a positive impact. In a revision of studies, Arpini (Reference Arpini2003) highlights some studies in which the youths revealed that the time spent in the institutions was the best period of their lives, for having been able to establish affective bonds that lasted even after institutionalization. However, Alberto (Reference Alberto, Machado and Gonçalves2003) reports that the youths “continue to feel a deep void of a real home, with a real family” (p. 242).

External Shame and Self-criticism

Research shows that shame is one of the most powerful physiological stimulators of the threat system (Dickerson et al., Reference Dickerson, Gruenewald and Kemeny2004; Gilbert, Reference Gilbert and Weeks2014) and an important component in a variety of emotional problems. It is composed of two main components: External shame (thoughts and feelings about how one exists in the minds of others, usually considering that others see the self in a negative way, as undesirable or a target of rejection), and internal shame (focused on negative self-judgments) (Gilbert & Procter, Reference Gilbert and Procter2006). A process closely related to internal shame is self-criticism, self-to-self relationship of dominance-submission, where one part of the self accuses and condemns the other. Self-criticism may have different forms and different functions: The "Inadequate Self" when the self makes mistakes and feels sad or angry about it, usually for the purpose of correcting behavior; and the "Hated Self" when the self is seen as detestable, defective, worthless, usually with the purpose of hurting and attacking the self. Shame seems to place individuals in a ruminating, self-critical style, making them vulnerable to various difficulties (Cheung et al., Reference Cheung, Gilbert and Irons2004).

Shame and self-criticism have been associated with psychopathology and particularly with depression through the years (Andrews & Hunter, Reference Andrews and Hunter1997; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Zuroff and Shapira2009; Luyten et al., Reference Luyten, Sabbe, Blatt, Meganck, Jansen, De Grave, Maes and Corveleyn2007; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Zuroff, McBride and Bagby2008).

Richter et al. (Reference Richter, Gilbert and McEwan2009) found that memories of feeling threatened in childhood were related to current self-criticism and depression. Similarly, Irons et al. (Reference Irons, Gilbert, Baldwin, Baccus and Palmer2006) found that self-criticism mediated the link between early childhood recall of negative rearing and depression, while Whelton & Greenberg (Reference Whelton and Greenberg2005) suggested that it is the emotions in the criticism (anger and contempt) that are linked to its impact on mood. Pinto-Gouveia et al. (Reference Pinto-Gouveia, Castilho, Matos and Xavier2013) found a significant mediation of self-criticism in the relationship between the centrality of shame and depressive symptoms.

Some studies have explored how shame and self-criticism explained psychopathology and the relationship between the two variables in this explanation. Castilho et al. (Reference Castilho, Pinto-Gouveia and Duarte2016) reported that self-criticism partially mediated the relationship between shame and psychopathological symptoms, in particular the "Hated Self", which suggests that fear of being devalued in the mind of others has a significant impact on people’s psychological well-being and this effect can be partially explained by self-criticism, but also reported an alternative model in which shame mediates the link between self-criticism and psychopathological symptoms and that was also significant, which is explained by the authors through the possibility that self-criticism and shame enhance one another in a circular and mutually interactive way. The study highlighted that the two forms of self-criticism are indeed separate types because they show different patterns of association with psychopathology. Another study with patients suffering from eating disorders has tested a similar model in which shame mediated the link between self-criticism and the eating disorder and revealed that it is a significant mediator in this relationship (Kelly & Carter, Reference Kelly and Carter2013).

In a study, comparing non-institutionalized adolescents and institutionalized adolescents of the same age (13–17), institutionalized adolescents showed higher levels of internal and external shame, self-criticism, fears of compassion and depression, and less early memories of warmth and safeness (EMWS). The difference in the self-criticism variable is noted, mostly, in the Hated Self form, emphasizing that these young people have much more of a harmful and destructive self-criticism, which does not have the function of correcting behaviors, but rather hurting and attacking the self (Santos & Salvador, Reference Santos and Salvador2018).

Depression

Depression, a common problem in adolescence, is marked by feelings of sadness and/or loss of interest in previously appreciated activities, reducing the individual’s ability to function, Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th Ed., DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Stevens (Reference Stevens2009) reported the association between symptoms of depression and social anxiety (AS) and higher risk behaviors in institutionalized adolescents. There are several studies that focus on depression in institutionalized adolescents (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Loflin and Doucette2015; Cummings, Reference Cummings2016; Miklowitz, Reference Miklowitz2015; Stoner et al., Reference Stoner, Leon and Fuller2015). Stoner et al. (Reference Stoner, Leon and Fuller2015) highlighted in their study that "depression is one of the most commonly diagnosed disorders in children and adolescents in the foster care system with prevalence rates up to three times that of same aged peers, and associated with long-term negative outcomes such as greater substance use, suicidality and psychiatric hospitalization" (p. 784). He also points out that the vulnerability is not only related to the life history before the foster care, but also to the experience, not always positive, lived during the foster care period. Some of these experiences could be related to placement changes, the stigma of being in foster care, or experience of abuse or neglect during the period of time the youth lived in a residential facility (Stoner et al., Reference Stoner, Leon and Fuller2015).

On the other hand, Cunha et al. (Reference Cunha, Martinho, Xavier and Espírito Santo2013) reported a protective effect of memories of warmth and safeness in childhood on the development of depressive symptoms in adolescence and Salazar et al. (Reference Salazar, Keller and Courtney2011) concluded that social support had a direct effect on depressive symptoms as well as moderation and a partial mediation effect on the relationship between maltreatment and depression. However, this last effect appears to diminish as maltreatment histories become more complex. In fact, the early childhood experiences, especially those related to feelings of threat or safeness, seems to play a key role on emotional and social subsequent development (Gilbert & Perris, Reference Gilbert and Perris2000).

McMillen et al. (Reference McMillen, Zima, Scott, Auslander, Munson, Ollie and Spitznagel2005) found a lifetime prevalence rate of 27% for major depression among a group of 17-year-old youths in the foster care system. Anderson and Simonitch (Reference Anderson and Simonitch1981) suggested that reactive depression was very common when the youths left foster care. Although they initially feel free by leaving the system, they quickly experience fear and feelings of loneliness when they realize that often they do not have the adequate resources to meet life’s demands.

Objectives and Research Hypotheses

The high rate of depression in children and adolescents in foster care and the increased risk of adverse outcomes over time highlight the importance of identifying factors that contribute to higher rates of this disorder and thus identifying the most useful and effective interventions. EMWS can be a protective factor in the prevention of psychopathology, as opposed to shame and self-criticism. To our knowledge, there are no studies that have explored the relationship between the above variables and their weight in depression in a sample of institutionalized adolescents in Portugal. Thus, the present study aimed to study variables that contribute to depression in this target population. It was hypothesized that: Depression would correlate negatively with EMWS (H 1) and positively with external shame and self-criticism (H 2), while the latter two variables would correlate positively with each other (H 3); EMWS would have a negative association with depression (H 4) and this relation would be mediated by external shame and self-criticism (H 5). In relation to the last hypothesis formulated, as self-criticism is considered a mechanism to deal with shame, we considered that the two variables should appear sequentially, similar to other studies done with another type of samples (Castilho et al., Reference Castilho, Pinto-Gouveia and Duarte2016; Martins et al., Reference Martins, Macedo, Carvalho, Pereira and Castilho2020; Pinto-Gouveia et al., Reference Pinto-Gouveia, Castilho, Matos and Xavier2013; Shahar et al., Reference Shahar, Doron and Szepsenwol2014), in this case with shame being a mediator between EMWS and self-criticism, exploring a double mediation between EMWS and depression.

Method

Participants

In order to test the aforementioned hypothesis, a cross-sectional study involving institutionalized youths, living in residential facilities for children and youths, was carried out. The exclusion criteria of the study were: 1) Age below 13 or over 18 years old; 2) evidence of randomness in response to questionnaires; 3) difficulty understanding the items of the questionnaires. Five participants were excluded from the study for evidence of randomness in response and eleven participants who had cognitive impairment and to whom the questionnaires needed to be administered by the researcher, were excluded for difficulty understanding the items. Formal collaboration proposals were sent to the institutions from the country that welcome children and youths between 13 and 18 years old, and questionnaires were applied to those that agreed to collaborate within the period defined for the completion of this study. Adolescents from 15 institutions from northern, central and southern Portugal participated.

The convenience sample consisted of 171 participants, 68 (39.8%) male and 103 (60.2%) female, with a mean age of 15.56 (SD = 1.49). There were no gender differences in the distribution of the variable age, t(160.579) = –1.96; p = .052. Regarding the variable year of schooling, the 9th grade was the most prevalent, constituting 22.8% of the sample. The average number of years of schooling was 8.54 (SD = 1.90). There were no significant gender differences in this variable, ![]() $ {\unicode{x03C7}}^2 $(8) = 9.28; p = .319, nor with respect to the number of failures, t(157) = 0.92; p = .359. There were also no significant differences in socioeconomic status between genders,

$ {\unicode{x03C7}}^2 $(8) = 9.28; p = .319, nor with respect to the number of failures, t(157) = 0.92; p = .359. There were also no significant differences in socioeconomic status between genders, ![]() $ {\unicode{x03C7}}^2 $(1) = 0.71; p = .401.

$ {\unicode{x03C7}}^2 $(1) = 0.71; p = .401.

Measures

The Forms of Self-Criticizing and Reassuring Scale for Adolescents (FSCRS-A; Silva & Salvador, Reference Silva and Salvador2010) is the Portuguese version for adolescents of the Forms of Self-Criticizing and Reassuring Scale (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Clarke, Hempel, Miles and Irons2004). It aims to evaluate the different forms and functions of self-criticism and self-reassurance, relating them to how individuals act in situations of failure. It has 22 items, and three subscales: the Inadequate Self, the Reassuring Self, and the Hated Self. It allows to obtain a total result of self-criticism (summing up the two factors of self-criticism – the Inadequate Self and the Hated Self) and partial results for each subscale. In the present study, despite presenting data related to internal consistency and correlation with other variables for each subscale of this test, we will only use the total factor of self-criticism in the mediated mediation model. In the present study, the internal consistency for the scales and the self-criticism factor ranged from .84 to .89 in the sample of institutionalized youth.

The Other as Shamer Scale for Adolescents – brief version (OAS-B-A, Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Xavier, Cherpe and Pinto-Gouveia2016) is an adaptation for adolescents of OAS–2 for adults (Matos et al., Reference Matos, Pinto-Gouveia, Gilbert, Duarte and Figueiredo2015), which in turn is a short version of the original adult scale (Other as Shamer Scale - OAS, Goss et al., Reference Goss, Gilbert and Allan1994). It aims to assess external shame, how adolescents think about the way others see them, through 8 items. Although the original scale (OAS) has presented a factorial structure formed by three factors, the OAS–2 and OAS-B-A are unifactorial. In the present study the internal consistency of the OAS-B-A was .91.

The Early Memories of Warmth and Safeness Scale for Adolescents – brief form (EMWSS-A – brief form, Vagos et al., Reference Vagos, da Silva, Brazão, Rijo and Gilbert2016) is the short Portuguese version of the Early Memories of Warmth and Safeness Scale for Adolescents (EMWSS-A, Richter et al., Reference Richter, Gilbert and McEwan2009). It evaluates experiences of warmth and safeness in childhood through 9 items. In the present study, its value of internal consistency was .93.

The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale–21 (Leal, Antunes et al., Reference Leal, Antunes, Passos, Pais-Ribeiro and Maroco2009) is the Portuguese version of Depression Anxiety Stress Scale of Szabó (Reference Szabó2010) adapted for children and adolescents from the scale of Lovibond and Lovibond (Reference Lovibond and Lovibond1995). The scale consists of 21 items that are distributed in three dimensions with seven items each: Depression, Anxiety and Stress, always referring to the extent to which the individual experienced each symptom during the last week. In the present study, an internal consistency value of .88 was obtained for the subscale of Depression.

Procedure

Authorizations were obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University and from the National Commission for Data Protection.

Prior to the application of the evaluation protocols, a request for formal collaboration was presented to the institutions and, for those who accepted to collaborate, a written request for consent was also obtained from the adolescents’ legal tutors. Finally, the adolescents that were allowed to participate were also asked to sign an informed consent form to ensure the voluntary nature of their participation. The protocols were applied after the participants return from school, in the institution’s study rooms.

The research protocol was completed in an average time of 40 minutes, and had two counterbalanced versions to prevent effects of response contamination or fatigue.

Analytical Strategy

Data collected through the research protocol was treated using the SPSS program (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences – version 23) for Windows and the PROCESS computing tool for SPSS (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013).

Normality was tested through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and deviations to normality through skewness and kurtosis. Descriptive statistics were calculated for each of the variables under study. To classify the socioeconomic status (low, medium, high) the classification of Simões (Reference Simões1994) was used. The gender differences were verified through Student’s t-tests for independent samples, in the case of continuous variables, and with Chi-square tests in the case of categorical variables. The interpretation of effect size was based on Cohen’s (Reference Cohen1988) criteria, where Cohen’s d values of .2 represent small, .5 medium, and .8 high effects.

The internal consistency analysis was also performed for each of the instruments and their respective factors. A Cronbach alpha value of less than .60 was considered inadmissible, between .61 and .70 as weak, between .71 and .80 reasonable, between .81 and .90 good, and above .90 very good (Pestana & Gageiro, Reference Pestana and Gageiro2008).

Pearson’s parametric test was used to calculate the correlations between the variables under study, considering correlations from .10 to .30 small, from .30 to .50 moderate and > .50 large (Cohen, Reference Cohen1992). Correlations were also obtained between the variables under study and socio-demographic variables to identify possible covariates to be introduced in the model.

To calculate the intended sample size, an analysis of statistical power was conducted. To detect medium effects, with the power of .95 and an alpha of .05, taking into account the planned statistics, G power suggested 89 participants (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner and Lang2009).

To examine whether EMWS were associated with depression in institutionalized adolescents through external shame and self-criticism, a mediated mediation model was estimated with PROCESS (Model 6 in Hayes, Reference Hayes2013). The indirect or mediator effect was analyzed through the bootstrapping procedure (using 10,000 re-samples), which creates 95% corrected bias and accelerated indirect effects confidence intervals, which are considered significant if zero is not contained within the lowest and highest value of Confidence Interval. Significance was set at .05 level.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

There were no significant deviations from normality in the variables under study. Although outliers were detected, they were not removed from the sample for reasons of ecological validity. The correlations between the variables under study and the socio-demographic variables, age and gender, were tested. Gender was included in the model as a covariate since its correlation with the dependent variable is close to what is considered a moderate correlation (Cohen, Reference Cohen1992). Age showed only low or very low correlations with every study variable and was therefore not included in the subsequent models.

Correlations

Table 1 shows the Pearson correlations between the variables under study, as well as the socio-demographic variables age and gender. Depression was negatively and significantly correlated with EMWS and positively and significantly correlated with external shame and self-criticism.

Table 1. Correlations between Variables in Study

Note. EADS_Depression = Dimension Depression of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21; EMWSS-A = Early Memories of Warmth and Safeness for Adolescents – short version; OAS-B-A = Others as Shamer Scale for Adolescents – brief version; FSCRS_A_Self-crit = Self-Criticism Factor of Forms of Self-Criticism and Self-Reassuring Scale for Adolescents; FSCRS_A_Inadeq = Inadequate Self subscale of Forms of Self-Criticism and Self-Reassuring Scale for Adolescents; FSCRS_A_Hated = Hated Self subscale of Forms of Self-Criticism and Self-Reassuring Scale for Adolescents.

* p < .05. ** p < .01.

Mediator Role of External Shame and Self-Criticism in the Relationship between Early Memories of Warmth and Safeness and Depression

In this section, we sought to explore, through a mediated mediation model, whether the effect of EMWS on depression would be mediated by external shame and self-criticism. Gender was introduced into the model as a covariate given the significant correlation with depression.

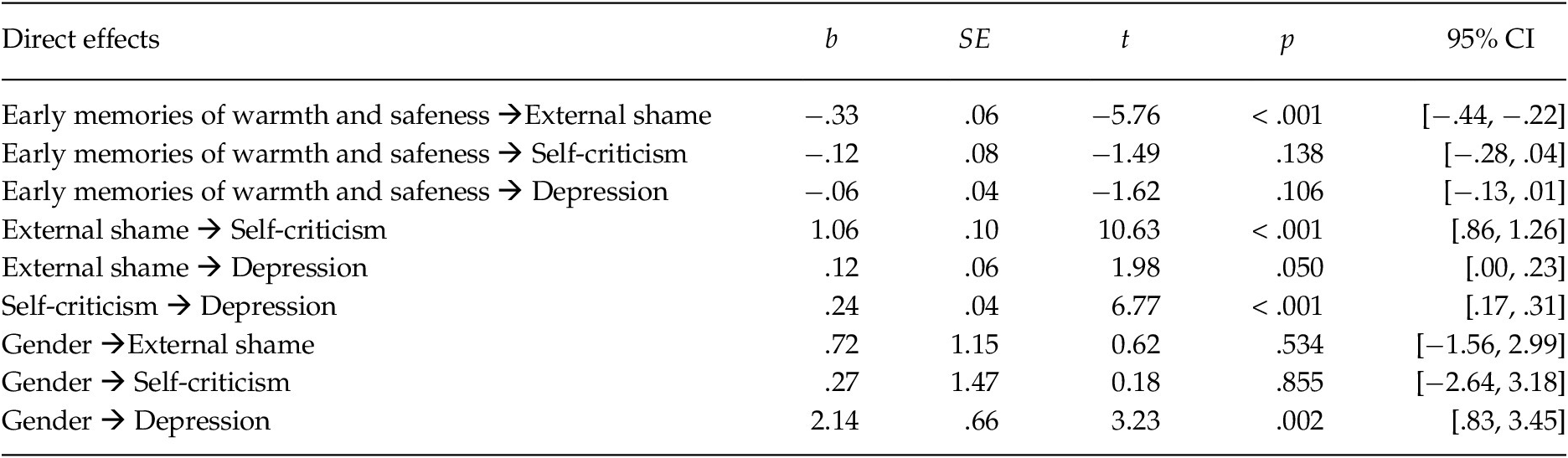

As shown in Table 2 and represented in Figure 1, the EMWS presented a negative and significant association with external shame, explaining 18.2% of its variance, while gender presented no significant association with this variable. External shame was positively and significantly associated with self-criticism, explaining 49.29% of its variance, while EMWS and gender presented no significant association with this variable. Finally, self-criticism and gender presented a positive and significant association with depression, explaining 52.6% of its variance, while EMWS and external shame presented no significant association with depression.

Table 2. Direct Effects for the Model Represented in Figure 1

Note. b = non standard regression coefficient; SE = standard error; p = statistical significance; CI = Confidence Interval.

Figure 1. Statistical Diagram of the Mediated Mediation Model for the Possible Influence of External Shame and Self-criticism on the Association between Early Memories of Warmth and Safeness and Depression, with Gender as a Covariate

Note. Path values represent the non-standard regression coefficients. In the arrow that links the Early Memories of Warmth and Safeness to Depression, the value outside parentheses represents the total effect of the Early Memories of Warmth and Safeness on Depression. The value in parentheses represents the direct effect of the bootstrapping analysis of the Early Memories of Warmth and Safeness on Depression after the inclusion of the mediators.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

The total effect of EMWS on depression was negative and significant, and the gender positive and significant (see Table 3), explaining both 19.5% of the variance. The direct effect of memories on depression did not reach significance (see Table 2).

Table 3. Total Effects for the Model Represented in Figure 1

Note. b = non standard regression coefficient; SE = standard error; p = statistical significance; CI = Confidence Interval.

The only significant specific indirect effect found was that of EMWS on depression through external shame and self-criticism (Table 4).

Table 4. Indirect Effects for the model Represented in Figure 1

Note. b = non standard regression coefficient; SE = standard error; CI = Confidence Interval

In brief, the results showed that external shame and self-criticism completely mediated the effect of EMWS on depression, making the connection between memories and depression not significant in the whole model.

Discussion

Given the relevance of institutionalization and its negative impact on psychological adjustment, as well as the effect of shame and self-criticism in the development of psychopathology, the present study aimed to analyze the relationships between all these variables in a sample of institutionalized adolescents, as well as to explore the mediating role of external shame and self-criticism in the relationship between EMWS and depression in this population. The EMWS didn’t show a direct effect on depression, exerting its effect indirectly through external shame and self-criticism. The relationship between EMWS and self-criticism was fully mediated by external shame, and the relationship between external shame and depression was fully mediated by self-criticism.

The correlations went in the expected way, with depression correlating negatively with EMWS (H 1) and positively with external shame and self-criticism (H 2), while the latter two variables correlated positively with each other (H 3). The correlations of EMWS with depression and with self-criticism were higher than the value obtained in the study of the Portuguese version of the EMWS-A, which also included a sample of institutionalized adolescents and used the same instruments (Vagos et al., Reference Vagos, da Silva, Brazão, Rijo and Gilbert2016). The EMWS showed a negative association with both variables, which is in line with previous studies showing the effect of adverse life experiences in the development of psychopathology (Irons et al., Reference Irons, Gilbert, Baldwin, Baccus and Palmer2006; Richter et al., Reference Richter, Gilbert and McEwan2009). It is therefore understandable that memories of warmth and safeness have the opposite effect.

The self-criticism Hated Self form related more strongly with depression than the form Inadequate Self; these results are also in line with studies involving other populations (Castilho et al., Reference Castilho, Pinto-Gouveia and Duarte2016; Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Clarke, Hempel, Miles and Irons2004). The Hated Self has usually the purpose of hurting and attacking the self and not of correcting behavior, which could explain its higher correlation with psychopathology.

Regarding the model studied, it was found some evidence in line with the working hypothesis, with EMWS having a negative association with depression (H 4), and with external shame and self-criticism fully mediating this relationship (H 5). More specifically external shame fully mediated the relationship between EMWS and self-criticism, and self-criticism fully mediated the relationship between external shame and depression. Our results suggest that a significant part of the depression in institutionalized adolescents could be explained by these variables, with 53% of the variance of depression being explained by this model.

The effect of self-criticism in the relationship between external shame and depression is in line with Castilho et al. (Reference Castilho, Pinto-Gouveia and Duarte2016) study, where the same variables and versions of the same instruments were used in a clinical sample. The mediation found in the above mentioned study was only partial, but in our study the results indicated a full mediation. This seems to suggest a process of internalization in the youth, in which what they think to be the view of others in relation to themselves seems to have an important weight in the construction of their self-image.

Our model shows a possible trajectory between these variables. Memories of warmth and safeness in childhood, usually associated with the family, seem to have an effect in the thoughts and feelings about how one exists in the minds of others (external shame). This construction in the institutionalized youth will be clearly deteriorated since, in most cases, the situations that lead to institutionalization are maltreatment and parental neglect. In trying to find meaning for the neglect experienced, the child, in a self-referential style that characterizes this phase of development, perceived herself as the reason for this lack of warmth and affection on the part of the caregivers, which would lead to a vision of self as inadequate and inferior (shame), which, in turn, would lead to the development of self-criticism. On the other hand, blaming oneself and not the other allows the relationship to be maintained (especially when one cannot leave), since blaming the other may involve some risk (Gilbert & Irons, Reference Gilbert, Irons and Gilbert2005). Strecht (Reference Strecht1997) reports that the inability of parents to take care of their children is seen by the child as their own fault, inasmuch as they have not been able to recover them.

There was no direct effect of the EMWS in self-criticism, which suggests that the effect of this variable in self-criticism is through the development of external shame. On the other hand the self-critical style of relationship with the self will maintain the view that others see him/her as inferior or a rejection target (Cheung et al., Reference Cheung, Gilbert and Irons2004).

Gilbert and Irons (Reference Gilbert, Irons, Allen and Sheeber2009) had already reflected on the relationship between what we think is the evaluation of others and the self-assessment, indicating that the second can derive from the first. Since depression is linked to a negative view of one’s self and others, it is understandable that the relation between EMWS and depression can go through the two variables: Shame and self-criticism, which leads precisely to this vision and its maintenance. Gilbert et al. (Reference Gilbert, Baldwin, Irons, Baccus and Palmer2006) point out that the contribution to depressive symptoms by self-criticism arises from suffering due to negative feelings about the self and the impairment of the capacity to generate feelings of self-compassion, and various studies referred the effect of self-criticism on the development and maintenance of depression (Beck, Reference Beck1964; Cantazaro & Wei, Reference Cantazaro and Wei2010; Gilbert & Procter, Reference Gilbert and Procter2006).

This study points out the relevance of evaluating and addressing external shame and self-criticism in the treatment of depression in institutionalized adolescent and reinforces the relevance of the use of therapies that directly address these variables (Gilbert & Procter, Reference Gilbert and Procter2006). Compassion focused therapy (Gilbert & Procter, Reference Gilbert and Procter2006) is a therapeutic approach specifically directed to people with high shame and self-criticism, and whose early rearing environments were/are generally difficult and hostile (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Kaminski and Herrington2019), such as those where the institutionalized adolescents live. For this population, being self-compassionate is a very difficult task and generates high levels of anxiety (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Baldwin, Irons, Baccus and Palmer2006; Gilbert & Procter, Reference Gilbert and Procter2006). It is important, however, to offer an alternative way of self to self relationship that could improve their quality of life and psychological adjustment, in preventive and therapeutic approaches. We therefore believe that institutionalized youths may benefit from an intervention focused on self-compassion, which proved to be effective in the few studies conducted with this population (Pace et al., Reference Pace, Negi, Dodson-Lavelle, Ozawa-de Silva, Reddy, Cole, Danese, Craighead and Raison2013; Reddy et al., Reference Reddy, Negi, Dodson-Lavelle, Ozawa-de Silva, Pace, Cole, Raison and Craighead2013).

In addition to all the implications at the clinical level, the study also gives an insight of the important role that the institutions, that have the legal and moral responsibility for caring and meeting the needs of young people, have in promoting healthier memories, positive experiences and emotional stability, which unfortunately, in many cases, could not be provided by the families. Silva and Bizarro (Reference Silva and Bizarro2011) reported differences in well-being according to the characteristics of each institution, verifying that the institution where young people reported greater well-being resembles a home, in terms of physical space and functioning.

Despite the relevance of this study, some methodological limitations should be considered. We note, first of all, that a convenience sample was used. Although we have tried to make it as representative as possible, including institutions from different places of the country, we recognize that this method of sampling has implications in the generalization of the results. On the other hand, the fact that it was not a longitudinal study is another limitation, not allowing us to follow change over time and relate, more consistently, the development of psychopathology with the exposure to different childhood experiences. We also considered that the language in some of the instruments used could be difficult to understand by young people in this age group, and that the use of other types of instruments, such as interviews, could have provided us with a more comprehensive view on the impact of these variables on each adolescent.

Despite these limitations, this study may be useful for research and clinical practice, concluding that the way the individual sees and relates to the self seems to impact on psychological adjustment and in the development of psychopathology. The findings of this study are even more important as there are few studies of these variables with this target population, offering a starting point for further investigation on this topic. It reinforces the importance of offering these young people a healthier alternative to their self-critic way of relating with the self, giving them the possibility of choice that they may not have had before.