Eleven issues ago TEMPO published a brief profile of the composer Naomi Pinnock. It was an interview that ranged across many topics: from Pinnock's childhood aspiration to be a doctor to her discovery of ‘the satisfying feeling of making things’ that would later consolidate in a vocation as a composer; from the conservatism of classical concert presentation to her memory of how in her teens she ‘subconsciously began to collect female [artist] role models’. What she had to say about musical form was particularly interesting:

Ah yes, form. You can't live with it and you can't live without it. It can become a straitjacket if you're not careful. The best case scenario is that it's a fluid kind of vessel that shifts sympathetically with the musical material. I'm totally fascinated by form and constantly come back to it during the compositional process.Footnote 1

Later in this article I will return to the relationship between the material of Pinnock's music and the ‘vessel’ within which it finds its musical form, considering both what constitutes musical material and how form can become ‘fluid’. In an era in which composers, particularly those who like Pinnock are writing for the European new music festival circuit, tend to favour single-movement forms, she is unusual in the way in which she frequently creates works in which a series of relationships develops between two or more movements.

Pinnock was born in 1979 in Cleckheaton, West Yorkshire, in the north of England. After secondary school she went on to read for a music degree at King's College London, taking composition classes with Harrison Birtwistle, and then studied composition with Brian Elias at the Royal Academy of Music. So far, so typically English, but then she moved to Germany, to the Hochschule für Musik in Karlsruhe, where her teacher was Wolfgang Rihm, and she stayed in Germany, living in Berlin until 2020. After finishing her compositional studies Pinnock established a distinctively individual creative identity – if there is any discernible trace of her teachers’ music in her work then it is perhaps that of Birtwistle, whose music from the 1970s has a similar preoccupation with a reiterative musical development in which groups of sounds are juxtaposed, permutated and revoiced – and soon gathered an impressive array of festival commissions and performances, both in Germany and the UK.

For this article I will focus on Pinnock's music from the period between 2012 and 2019, an output framed by two works for string quartet, the latter with soprano too. This is not to suggest that her music from before 2012 is not significant – by 2010 her work was already sufficiently well regarded for her to be awarded the Berlin-Rheinsberger Kompositionspreis – but between String Quartet No. 2 (2012) and I am, I am (2019) there is a particularly clear process of refinement in her compositional method, a process made especially clear by a number of direct equivalences between these two pieces. I also want to locate Pinnock's work within a wider aesthetic landscape. Pinnock is usually scrupulously careful to identify other artists whose work she feels has influenced her, but I want to suggest that these influences are often more intricate and profound than she sometimes acknowledges.

(absolutely no pause!)

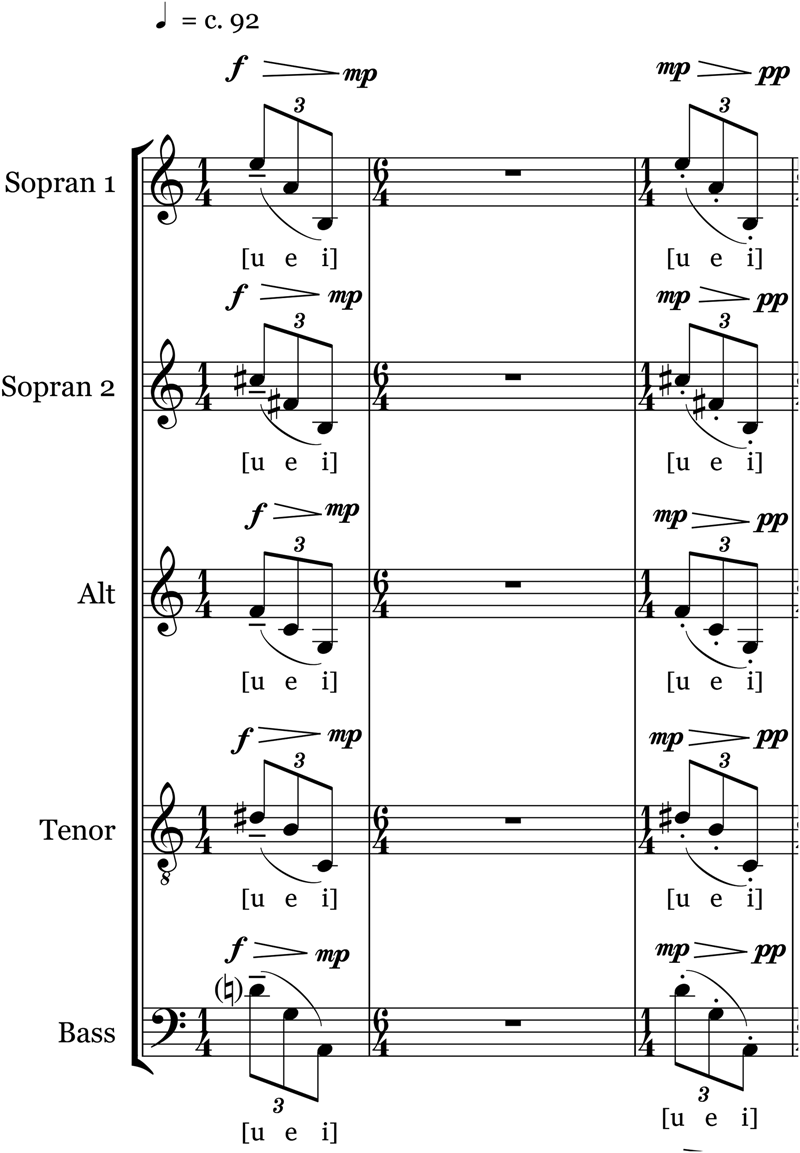

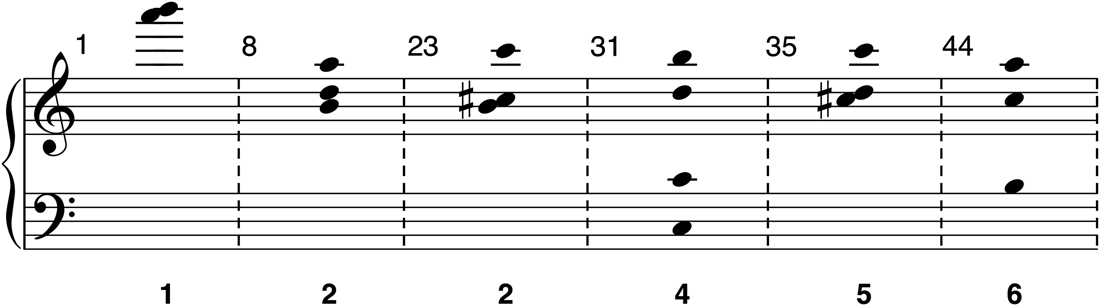

Naomi Pinnock's String Quartet No. 2 was commissioned by the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival and the Wittener Tage für neue Kammermusik and premiered by the Arditti Quartet in Witten in April 2012. It is a work of considerable intensity – indeed the expression mark at the head of the score is ‘with intensity’ – and its intensity is compounded by the music's restrictions, both in time and material. Altogether the quartet plays for just 13 minutes: the first movement lasts a little under eight minutes, of which the first two minutes are a solo for the viola player; the second movement is a little over five minutes long. Within these modest dimensions Pinnock presents material that is also tightly limited. Almost everything that will occur in the entire work can be traced back (it is telling that the first movement is entitled ‘retrace your steps’) to the first two lines of the score (see Example 1).

Example 1: Naomi Pinnock, String Quartet No. 2, bars 1–14.

This opening viola solo is a study in string crossing, as if the viola player is doggedly trying to find a way to make all four strings sound at once: sometimes the upper two strings are sustained beyond the initial bow-stroke (bars 1, 2, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12 and 13), sometimes the bottom two (bars 3 and 10), sometimes the middle two (bar 7). In the profile interview in TEMPO 283 Pinnock was asked whether she was concerned that classical music's reliance on notation was rather ‘old-fashioned’. She replied:

I would disagree that notation is old-fashioned in the same way that writing words down for people to speak is not old-fashioned. New technologies do not negate older ones. I love notation. It's a puzzle really. How do you go from hieroglyphics to sound?Footnote 2

The viola writing at the start of String Quartet demonstrates how rich in creative potential this journey can be: to read the score and listen to the recording of Ralf Ehler's performance of the solo with the Arditti QuartetFootnote 3 is to see and hear how ‘hieroglyphics’ become sound. Ehler's playing is, of course, metrically very accurate but there is a constant variation in the speed at which the bow travels across the strings and in the balance between the initially sounded strings and the strings that are sustained. The pent-up energy of this first page is the catalyst for the drama of the work as a whole yet so much of that energy is generated in the gap between notation and realisation.

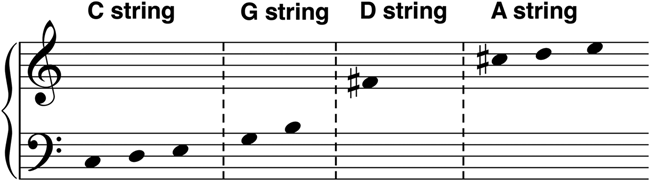

As I suggested earlier, energy is also generated by Pinnock's restriction of her musical materials. Three different, adjacent notes are assigned to each of the C and A strings and two, a major third apart, to the G string, their various permutations anchored by an F# pedal on the D string, giving a collection of seven different pitch-classes (see Example 2). It's a collection in which the gaps are as important as the adjacencies: the minor third between the low E and G and the perfect fifths between the B, F# and C# will become important later in the work. There is permutation of durations too: the shorter bow-strokes are either one or two quavers long, the longer ones are sustained for three, four or five quavers.

Example 2: Naomi Pinnock, String Quartet No. 2, pitch material, bars 1–49.

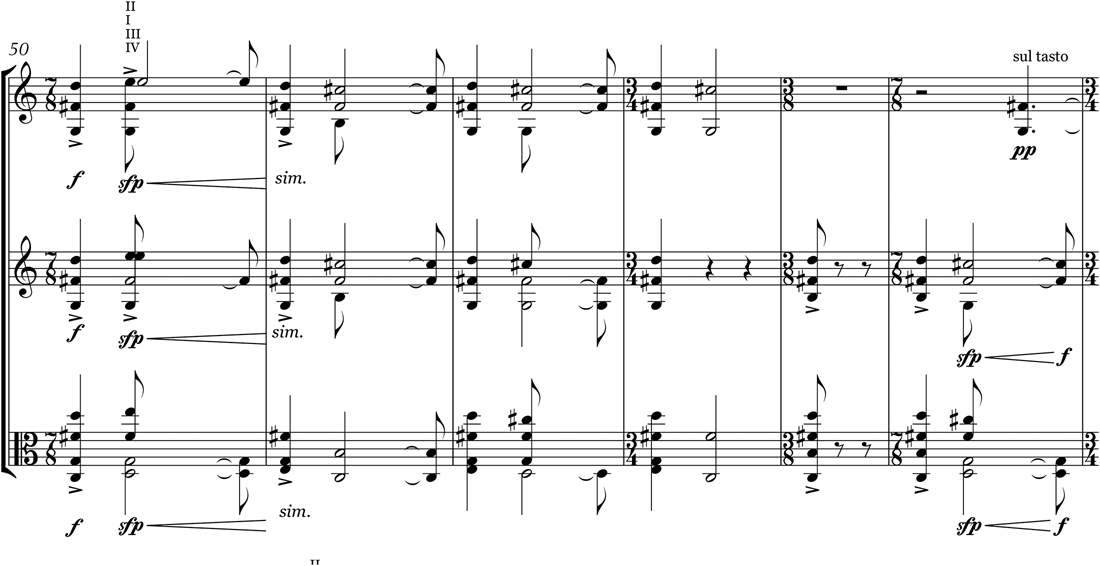

Then, after two minutes, two more members of the quartet join in. It's a tremendous moment, the soundworld suddenly brightened by the violins (see Example 3). With just a handful of exceptions each pitch-class introduced in the viola solo retains its registral position, but the addition of the violins means that the sound of up to six strings can now be sustained.

Example 3: Naomi Pinnock, String Quartet No. 2, bars 50–55.

At bar 76 there's another change: after one last crotchet bow-stroke across three strings the texture becomes more continuous and the dynamic quieter and eventually, in bar 92, the cello is introduced; in the recording of the Arditti Quartet's Witten premiere of the piece four minutes have passed. The cello introduces a new level of quietness (pp), a new playing technique (artificial harmonics) and new notes (F$, then G$, then A@) of which only the G has been heard before, three octaves below its new register.

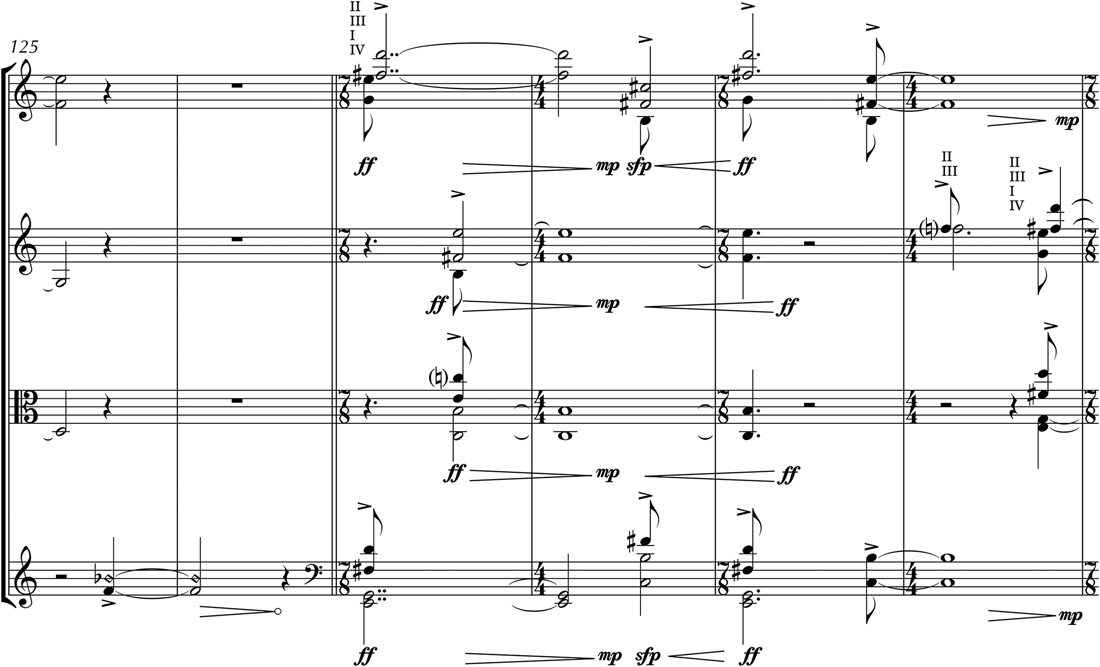

A little over a minute later the texture changes again, with a return to the string crossing bow-strokes of the opening, but played now by all four instruments (see Example 4). There's a continued insistence on the same seven pitch-classes on which the music has been based since it began, but now they are spread more widely, redistributed into new registers. The cello's insurgent F$ is occasionally heard in the violins and viola, always ff, always in the same register (on the top line of the treble stave), a dissonant disrupter. Sixteen bars from the end of the movement the first violin adds the other insurgent cello pitch, the A@, now respelt as G#; it comes four times, always ff, always in the same register (on the second line of the treble stave), each new entry 11 quavers after the previous one. It's the only exactly repeated event in the whole movement, as if the first violin is signalling that it's time to stop.

Example 4: Naomi Pinnock, String Quartet No. 2, bars 125–130.

The first movement ends with a final insurgent F$ from the second violin and viola, but there's no repose: over the double bar line Pinnock instructs ‘attaca (absolutely no pause!)’ and the second movement begins immediately. It is quieter, slower music than the first movement, not as densely textured, and returns the seven notes of the first movement viola solo to their original registers. But whereas the first movement was about notes being sounded together, about their vertical relationships, the second movement tilts the axis of the music through ninety degrees and focuses on linear relationships.

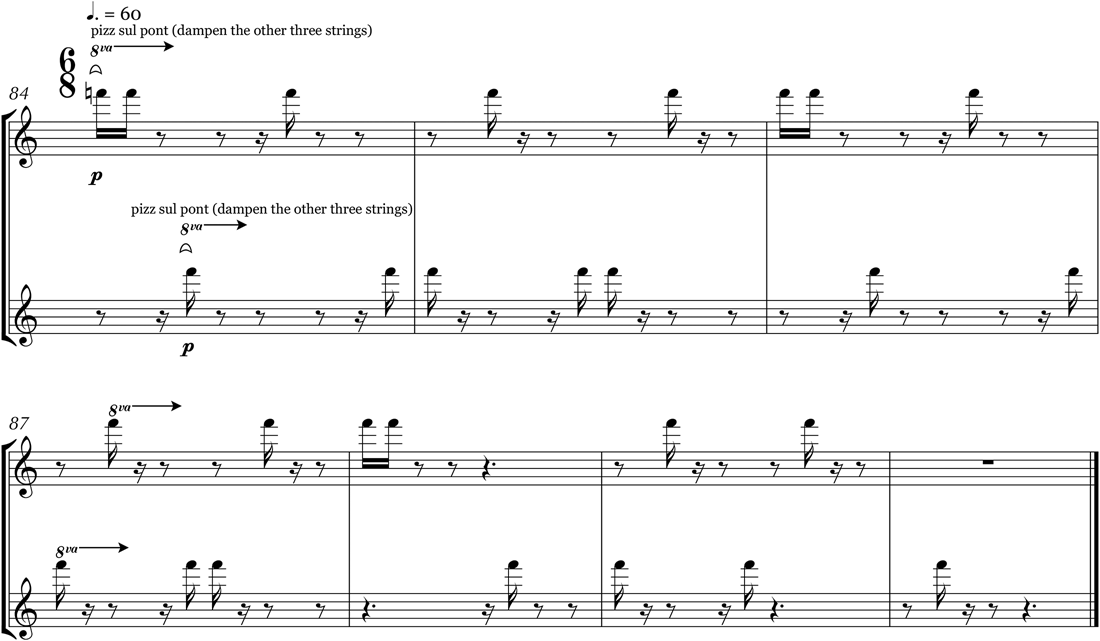

In particular, those intervallic gaps I mentioned earlier become a primary focus, especially the minor third between the E and G below middle C, which at the start of the first movement were the upper and lower extremes of the collections of notes on the viola's C and G strings (see Example 2). As the music progresses its stability is disturbed by a few more insurgent elements: an appoggiatura G falling onto the F# above middle C and a bottom C# on the cello, but before the music can turn into something else it stops. One last insurgent moment is saved for the coda: the high F$ that disrupted the end of the first movement returns, but now an octave higher still, as a sul ponticello pizzicato for the two violins (see Example 5). ‘Dampen the other three strings’ says the performance note; in 13 minutes we have come a long way, from the sustained sounding of the full length of multiple strings to these tiny clicks.

Example 5: Naomi Pinnock, String Quartet No. 2, bars 84–90.

Shine a light

As she was working on String Quartet No. 2 Naomi Pinnock was commissioned by Klangforum Heidelberg to create a new work for their Prinzhorn Project. The Sammlung Prinzhorn in Heidelberg was initiated between 1919 and 1921 by Hans Prinzhorn (1886–1933) as a museum of psychopathological art and is one of the most important collections of so-called Art Brut or ‘outsider art’. Prinzhorn and his fellow psychiatrist, Karl Willmanns, sent out a request to psychiatric institutions in the German-speaking countries for paintings, writings and other creative work by their patients and in 1922 Prinzhorn published a selection of the work he had gathered in Bildnerei der Geisteskranken Footnote 4 (‘Artistry of the Mentally Ill’), a book which had a considerable influence on the development of surrealism and has been regularly reprinted and translated ever since. Work from the collection was also shown in the Entartete Kunst exhibition that the Nazis toured in 1937, the Prinzhorn work intended to demonstrate the pathological nature of Modernism.

The Sammlung Prinzhorn continues to inspire artists. Per Nørgård's Symphony No.4 (1981) takes its two-movement form and their titles – ‘Indischer Roosen-Gaarten und Chineesischer Hexensee’ (Indian rose garden and Chinese witch sea) – from a ‘Musikbüchlein’ by the Prinzhorn artist Adolf Wölfli (1864–1930) and Nørgård's 1983 opera Die Göttliche Tivoli (The Divine Circus) is also based on Wölfli's writings. KlangForum Heidelberg's Prinzhorn Project began in 2001, commissioning new music based on works in the Sammlung, and the twenty-second of these commissions went to Naomi Pinnock, the first woman to be invited to be part of the project.Footnote 5

She visited the Prinzhorn archive and writes how ‘in the very first folder I opened … I found pages and pages of Jakob Br's notebooks and was immediately impressed by them’. The result was a single movement work for five solo voices (SSATB) of the ensemble Schola Heidelberg, The Writings of Jakob Br. (2013), and from all those ‘pages and pages’ Pinnock sifts out just two Latin words, ‘lumen’ (light) and ‘lucere’ (to shine). As in String Quartet No. 2 she is engaging in a radical reduction of musical means, but something of the essence of Jakob Br's creative practice is also being distilled. Pinnock describes Jakob Br's work as falling into two main types of activity: ‘page-long repetitions of similar-looking but indecipherable words and pages filled with patterns, often following a grid-like formation, with stripes and crosses but also sometimes with more organic shapes’. She was particularly ‘drawn to these pages of indecipherable could-be-words … and decided that I was going to attempt to decode them’.Footnote 6

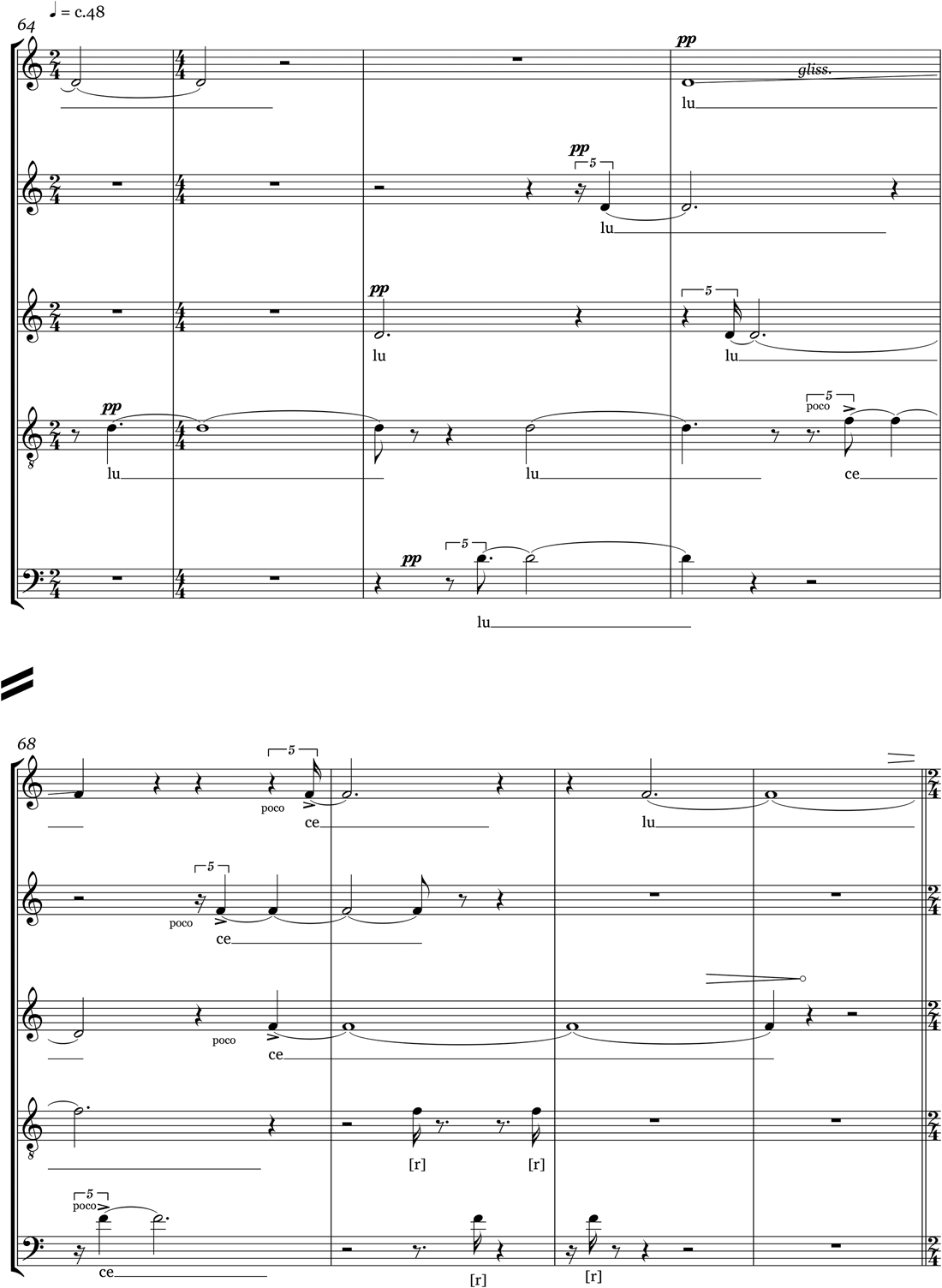

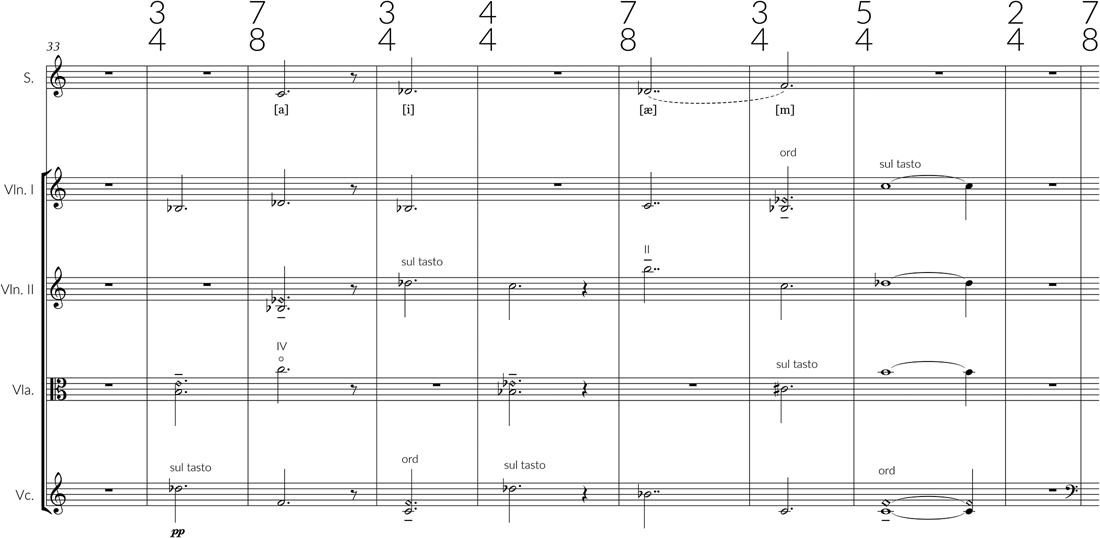

Through this decoding she found her two related Latin words, but the duality she found in Jakob Br's creative output also survives in The Writings of Jakob Br. Two different sorts of music alternate throughout: the first is a sort of unison exclamation in which the voices sweep down through a rapid succession of vowel sounds from the two Latin source words (see Example 6) and more continuously sung sounds, usually sustaining a single pitch, more often than not a D or an F (see Example 7).

Example 6: Naomi Pinnock, The Writings of Jakob Br., bars 1–3.

Example 7: Naomi Pinnock, The Writings of Jakob Br., bars 64–71.

It is probably simplistic to equate these two types of music directly with the pages of words or patterns that Pinnock found in Jakob Br's notebooks but the sense of two entirely separate sorts of utterance being repeatedly juxtaposed is very striking. Only in the last 30 seconds of the piece is there some sort of fusion: the voices sing sustained phrases in which the D above middle C is the most frequently recurrent note, but these phrases now have something of the variable energy of the exclamations, as if the continuous tones are being animated and destabilised (see Example 8).

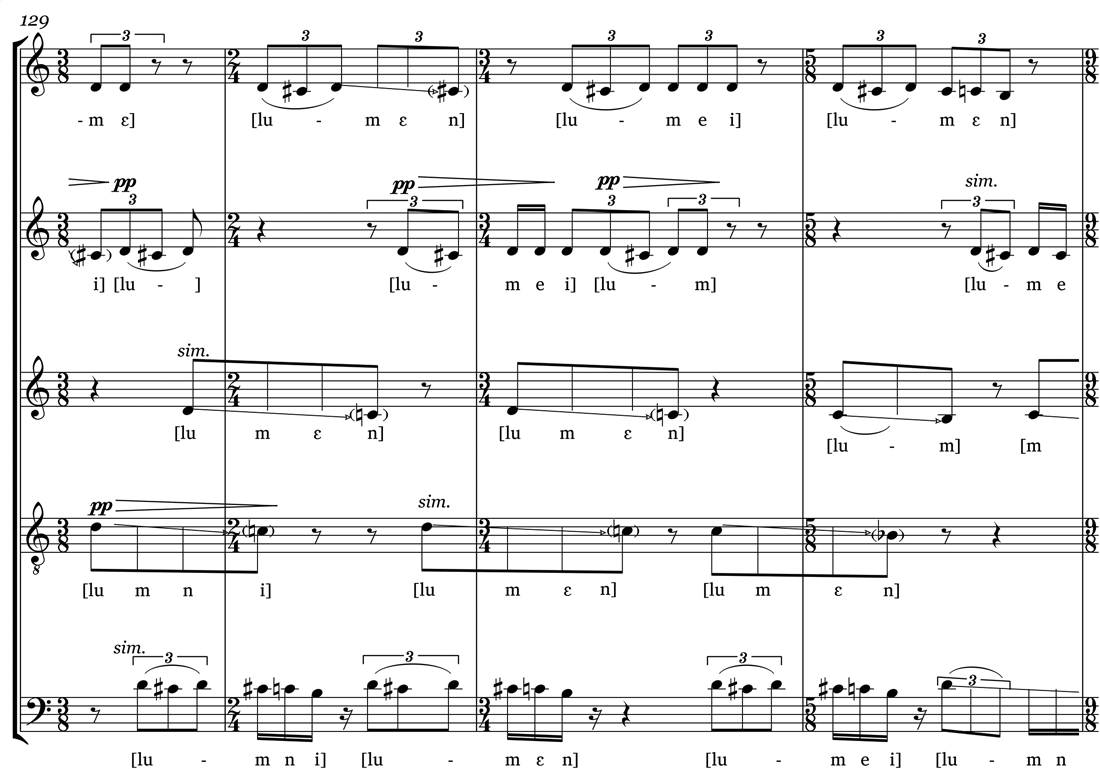

Example 8: Naomi Pinnock, The Writings of Jakob Br., bars 129–132.

‘A museum without dust’

In both String Quartet No. 2 and The Writing of Jakob Br. musical form is based on a set of dualities: an initial set of pitches that are challenged by what I have termed ‘insurgent’ pitches in the String Quartet; the two different types of singing in Jakob Br. These consolidate into larger formal divisions: the alternation of sections dominated by each type of singing in Jakob Br.; the two movements with their different axes in the String Quartet.

Music for Europe (2016), however, is more complex, a 20-minute-long work for instrumental quintet (flute doubling alto flute, clarinet, percussion, piano and harp) that was commissioned by Ensemble Adapter with funds from the Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation. There are five movements, of which all but the third have titles – I: ‘transparent lament’; II: ‘porous with loss (i); III; IV: ‘porous with loss (ii); V: ‘rising, rising’ – and even without the clues offered by these titles it is hard to imagine any listener not sensing a profound sadness in the music. In her programme note for the premiere at the 2016 Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival Pinnock explained the background to the piece:

Paul Klee created a text-painting using these words a hundred years ago, the year he was conscripted into, though never fought for, the German army. I saw this painting just days after the UK voted to leave the European Union. I was touched by its simple, fragile vulnerability made at a deeply fractured time.

Whether or not she was aware of it, the cultural resonance of the piece goes deeper still. Klee's ‘text-painting’ is based on a German translation of a poem by Wang Zeng Ru (465–522). The poem was included in a collection of Chinese verse, from ‘twelve centuries before Christ to the present day’, edited and translated into German (although at second-hand, from English and French primary translations) by Hans Heilmann.Footnote 7 Klee and his wife Lily had been given the volume as a Christmas present in 1909 by Lily's parents but Klee would later say that it was only in 1915 that he read the poem. Certainly it was at that point that he became fascinated by the idea of treating the German words as if they were Chinese pictograms: rather than the painting representing the meaning of the words the words would themselves define the painting in 1905.Footnote 8

Klee's painting is in two horizontal bands, with a blank space between the upper and lower sections. The proportions of the painting are roughly divisible by five, with each of the upper band and the blank space taking up about a fifth of the painting and the remaining three-fifths occupied by the lower band. The letter-forms that make up the title of the painting, Hoch und strahlend steht der Mond (High and radiant is the moon), articulate areas of colour in the top part of the painting. In the lower part of the painting the visual forms are created out of the words ‘Ich habe meine Lampe ausgeblasen, und tausend Gedanken erheben sich von meine Herzensgrund. Meine Augen strömen über von Tränen’. (I blew out my lamp, and thousands of thoughts rise up from the bottom of my heart. My eyes overflow with tears.)

Heilmann's translation of Wang's poem has a particularly British resonance. ‘The lamps are going out all over Europe, and we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime’, said the Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey at dusk on 3 August 1914, the night before Britain declared war on Germany and began the Great War. In 2016, as the UK entered the twilight of its membership of the European Union, the image of lamps being extinguished, whether the image be Wang's, Heilmann's or Grey's, had an especially painful poignancy for anyone with a sense of how the European Union had been built out of the devastation first launched in 1914.

I will return later to the ways in which Pinnock's Music for Europe connects to ideas about Europe; first I want to discuss how it relates to the work of Paul Klee. In particular it seems to me that Pinnock's music is a strikingly successful realisation of many of Klee's ideas about form. In her 2018 TEMPO profile Pinnock talked of form as a ‘fluid kind of vessel’Footnote 9 and one of the ways in which Klee's work is so distinctive is in its exploration of the many formal paradoxes of the two-dimensional picture-plane. By its very nature a painting can never be a fluid vessel – it is a flat surface, with fixed dimensions, usually inside a frame, usually attached to a wall – but Klee constantly experiments with illusions of formal fluidity. In a number of works from the early 1920s, such as the oil-transfers Stadt im Zwischenreich and Vogel = Inseln (both 1921), he chooses subjects (‘City between realms’, ‘Bird = islands’) whose very nature necessarily places them in a void: the city and the island both float in the centre of the canvas on a nebulous wash, forms without edges.

Elsewhere, in the pointillist paintings of the early 1930s, for example, Klee defines his formal vessel by painting right out to the edges of the image. The artist's signature itself can also be a framing device: in Stufen (‘Steps’) (1929) it is placed on the lowest of the horizontal stripes that go to the margins of the canvas, whereas in Vogel = Inseln it lies on the outer frame, centred at the bottom of the sheet of cardboard on which the paper of the oil-transfer is mounted. Or one type of depiction can be framed by another: in Um der Fisch (1926) Klee surrounds the declared subject of the work, a representation of a fish sufficiently naturalistic that a keen angler would be able to identify it, with a circle of more abstract symbols. The fish lies on a dish and seems to be both mortal and grounded, but the symbolic figures – a cone, a mandala – orbit freely; in this two-dimensional universe different force-fields can operate simultaneously, one framing the other.

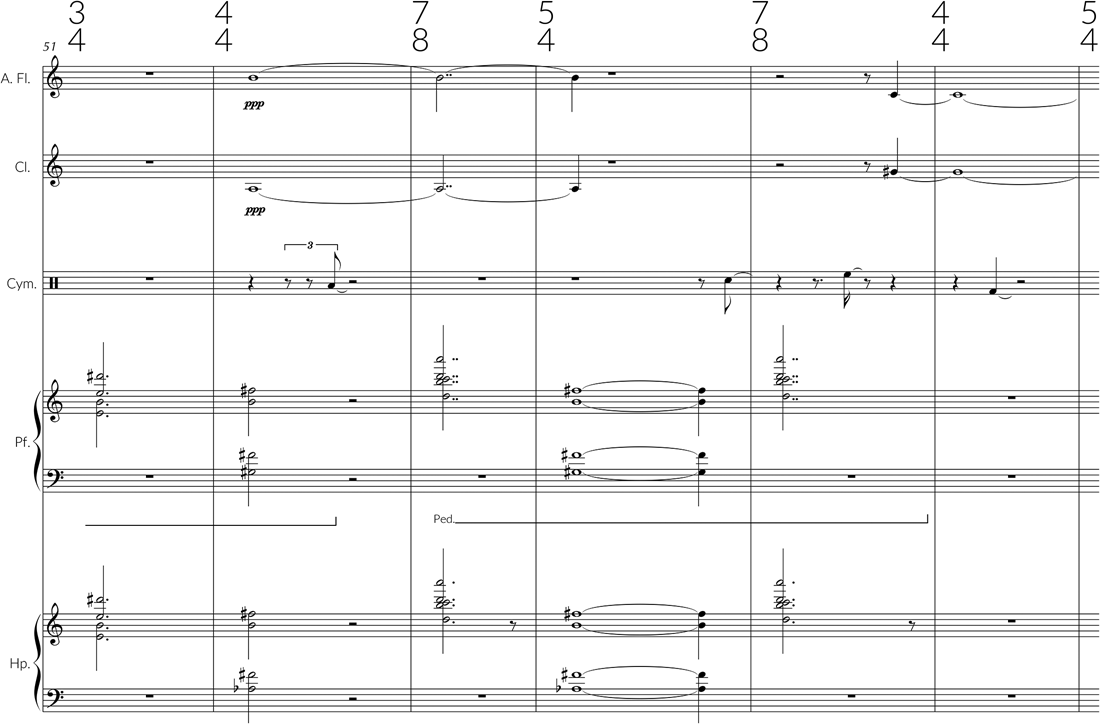

Something similar happens in Naomi Pinnock's music. In Music for Europe each of the five movements seems to occupy its space in time differently. In the first movement the clarinet provides a linear connection through the music, to which the other instruments sometimes chime in (Example 9 shows one of the fuller passages).

Example 9: Naomi Pinnock, Music for Europe, bars 20–26.

Movement III begins as a high flute solo, later accompanied, then replaced by an insistently repeated B@ at the top of the piano. Movement V is dominated by high, bell-like sonorities for bowed cymbal, piano and harp, the other instruments joining in with four sustained notes at the end (see Example 10). In between come the two ‘porous with loss’ movements in which the pianist and percussionist produce a white-noise texture, both of them rubbing ‘fine sandpaper on a plank of smooth wood//tile’; around this are the repeated sound of the harpist scraping a finger along a string and a handful of sustained notes for winds and vibraphone.

Example 10: Naomi Pinnock, Music for Europe, bars 51–64.

A year earlier Pinnock had written Lines and Spaces, a six-movement work for piano about which I will say more later in this article. In that work two different types of music are juxtaposed in the alternating movements, a formal division that is easy for listeners to apprehend at a first hearing but may also be too conventionally dialectical in its opposition of sonorities. In Lines and Spaces there are five movement-boundaries but only two sorts of juxtaposition: from slower to quicker music between movements 1 and 2, 3 and 4, and 5 and 6; from quicker to slower between movements 2 and 3, and 4 and 5. In Music for Europe the relationships between the movements are more subtle and more various, with the return of the noise-rich ‘porous with loss’ music reminding us that, as time passes, our perceptions change.

Is it too fanciful to suggest that the largescale formal division of Music for Europe is itself a homage to European culture? Note that double use of the ‘porous with loss’ title for the second and fourth movements and remember that Mahler's Symphony No. 7 (1905) is also divided into five movements of which two, the second and fourth, share the title ‘Nachtmusik’. Or, instead, remember Bartok's String Quartet No. 5 (1934), also in five movements, with two fragmentary slow movements framing the central scherzo. Or one more memory, the last of Schoenberg's Six Little Piano Pieces, op. 19 (1913): more bells tolling for a civilisation whose days are numbered, just as Pinnock does in the last movement of Music for Europe. In 1930 Will Grohmann edited a book about Klee that includes Um der Fisch, the painting I mentioned earlier, among its 33 black-and-white plates; as part of his contribution to the book the surrealist poet René Crevel wrote that ‘Klee's work is a complete museum of the dream, a museum without dust’.Footnote 10 Naomi Pinnock's Music for Europe has something of this quality too. In the clarity of its presentation, the variety of its musical forms and the economy of their expressive articulation it is similarly dust-free and, like all museums, it is pervaded with a sense of loss.

Island

If Paul Klee was a familiar point of reference for artists during the latter part of the twentieth century and into the current one, Agnes Martin has become ubiquitous in the last few decades, but whereas in Klee the relationship between form and content becomes part of the subject of the work, in Martin's work the distinction between form and content is erased. As Naomi Pinnock writes in the programme notes for Lines and Spaces (2015), ‘Martin's exquisitely simple paintings … are just grids and lines’.Footnote 11 One might rephrase this: because Martin's paintings are just ‘grids and lines’ they are, necessarily, ‘exquisitely simple’; there is no form, only content; no content, only form. To make a close examination of the surface of a Martin work is to discover that, yes, there was minutely varying human agency in its making but that agency is not part of the subject of the work as it might be in, say, a painting by Cezanne; instead it is just what was required for the work to come into being.

Perhaps I am misunderstanding what is represented by Martin's grids and lines; nevertheless it seems to me that, both in its form and its content, Naomi Pinnock's Lines and Spaces is perhaps rather too self-consciously ‘formed’ to capture the essence of Martin's work. Pinnock translates the concept of ‘space’ into piano sonority as a series of slow-moving harmonic fields, that of ‘line’ as a repeated middle C around which other notes are occasionally sounded. These two types of music are alternated, with movements 1, 3 and 5 presenting ‘spaces’ and movements 2, 4 and 6 ‘lines’, and they also occupy different amounts of time, with movement 3, the second ‘space’, taking up more than a third of the total duration of the work). The variation in scale is dramatic in a quite un-Martin-like way, and the juxtaposition of ‘line’ and ‘space’ music is similarly dramatic, recalling the dialectical oppositions of String Quartet No. 2 and The Writings of Jakob Br. rather than Martin's neutral grid patterns.

Listening to music is not like looking at paintings and, at least for this listener, listening to Naomi Pinnock's Lines and Spaces is not like looking at an Agnes Martin work. Perhaps Pinnock too was aware that she could go deeper in her musical exploration of the significance of Martin's aesthetic, because in her orchestral work The Field is Woven (2018, rev. 2019) she returned to the subject, taking her title from a remark by Donald Judd who, in a 1963 review of Agnes Martin's recent paintings, wrote that ‘the horizontal lines go through, but the irregular vertical gaps between the rows of dashes are dominant. The field is woven’.Footnote 12

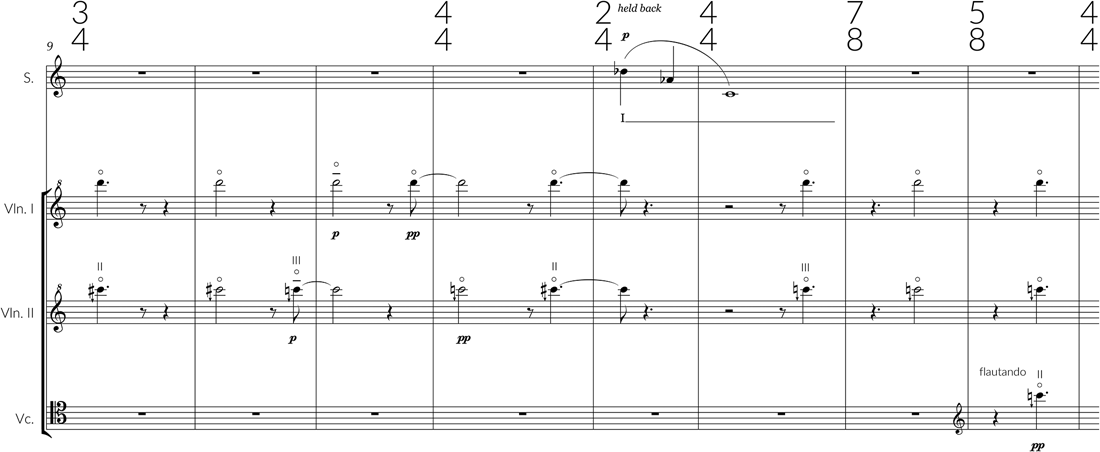

The Field is Woven is cast in a single movement, playing for a little under 13 minutes, and, as the title suggests, its composition has something to do with the lateral and longitudinal processes that link Agnes Martin's work to weaving, likened by Pinnock to ‘a sense of movement in and out, and repeatedly from side to side’.Footnote 13 In Pinnock's music this lateral axis becomes a gradual movement backwards and forwards through a series of (mostly) three-note pitch collections. Example 11 shows the first six of these collections with their component pitches in the registral position in which they first occur. The collections are introduced one by one (the numbers above the stave in Example 11 show the bar numbers in which each collection first appears) and in this first phase of the work's unfolding all are more or less present (the exception is collection 3 which is not heard again after bar 31) all the time, the music rocking back and forth between them: a melody of harmonic entities.

Example 11: Naomi Pinnock, The Field is Woven , initial pitch collections.

The music's longitudinal axis is not only the overall pitch-space available within the orchestra but perhaps also the orchestra itself: as the music evolves it has a set of pitch-locations from high to low and a set of positions within the physical space occupied by the orchestra so that, as each collection is voiced and revoiced, the music can move both in time and space. This process recurs three times within the work as a whole. From bar 71 the music begins a new evolution, this time opening out from the C# and D just above middle C, and at bar 118 there is a fermata, followed by an extended coda which occupies the entire pitch-space of the orchestra. The Field is Woven was commissioned by Ilan Volkov for the Tectonics Festival in Glasgow, where it was premiered by the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra in May 2018, and, like many of Volkov's commissions for the festival, it demonstrates how an orchestra that is so evidently devoted to new music can liberate a composer's imagination. The compositional techniques of The Field is Woven are familiar from earlier Pinnock but the orchestral setting makes possible a music whose sense of gravity and scale is unprecedented in her work.

… steps I tried to retrace

I am, I am (2019) for soprano and string quartet was written for Juliet Fraser and the Sonar Quartett. The soprano sings a fragment of text from the seventh of a sequence of 14 poems entitled ‘Tentsmuir’, from Rachael Boast's 2011 debut collection, Sidereal. Elsewhere in the collection, in ‘The Extra Mile’, Boast (b. 1975) describes light as ‘possessing a rainbow-body/the way metaphor possesses a poem/without ever disclosing how it did so’Footnote 14 and ‘Tentsmuir’ is similarly miraculous, mixing images of coniferous woodland and sea mist (Tentsmuir is a pine forest on the Fife coast) with references to the Old Testament story of Job and to the creative process. Each of the ‘Tentsmuir’ poems has 14 lines, and the sequence as a whole seems to be an account of a period of rehabilitation and healing, a gathering anew of personal and poetic resources. At the end of the fourteenth poem in the sequence Boast offers a conclusion:

Pinnock uses just six words from ‘Tentsmuir’, two of them repeated –

but the expressive concerns of Boast's sequence seem to permeate the music of I am, I am. Or perhaps Boast and Pinnock are kindred spirits?Footnote 15 In the work of both poet and composer there is the same careful progression, images savoured and developed step by step (indeed, the line about ‘the steps I tried to retrace’ anticipates the title of the first movement of Pinnock's String Quartet No. 2). Just as the ‘Tentsmuir’ sequence explores ideas of forest-sea-healing-poem, turn and turn about, until some sense of an ending is possible, so I am, I am slowly evolves out of its opening sonic sequence (see Example 12). The music has the same grave pace as The Field is Woven, long notes in the strings alternating two interrelated pitch collections, with the entry of the soprano introducing a third collection made up of notes from the first two collections. The steady tread of the music is also underpinned, at least initially, by a recurrent phrase-structure, repeated five times: two linked events, then a pause; two linked events, then a pause, three linked events, followed by a longer pause. Examples 12a and 12b show the first and last versions of the phrase.

Example 12a: Naomi Pinnock, I am, I am, first movement, bars 1–8.

Example 12b: Naomi Pinnock, I am, I am, first movement, bars 33–41.

As Example 12 also shows, the soprano's involvement in the music grows during this opening passage and, as she acquires more notes to sing, the overall trajectory of her part becomes consistently upward so that by the end of the first movement of I am, I am she has settled on the F at the top of the treble stave. After a brief coda, for the strings alone, a second movement begins, attaca (again an echo of String Quartet No. 2) with a C#–D dyad, but now the primary trajectory of the music is downward from this high, microtonally inflected reference point, the soprano singing falling figures, almost all of them permutations of a short-short-long gestalt (see Example 13).

Example 13: Naomi Pinnock, I am, I am, second movement, bars 9–14.

In its juxtaposition of different sorts of music – up, then down – I am, I am echoes aspects of Pinnock's earlier work, especially the dualities of String Quartet No. 2 and Writings of Jakob Br., but there's a singleness of purpose in this music too. That short-short-long gestalt in the soprano part in the second movement has a sense of musical inevitability, not only because the notes it articulates take us back, over and over again, to where she began in the first movement, but also because the phrase structure with which the first movement begins is also based on a short-short-long gestalt.

There's a paradox at the heart of Naomi Pinnock's music: its apparent formal simplicity belies a hidden richness of detail. Or, perhaps it is that very simplicity that allows for such a proliferation of possibilities. Pinnock's patient, painstaking refinement of her musical world has been a process of growth, of steps taken, but it has also been a process of steps retraced, of regeneration. As Rachael Boast writes in the final poem of the ‘Tentsmuir’ sequence, ‘You have fed back into yourself’.