Introduction

Sexual and gender diversity has been ubiquitous throughout the history of the human species (see Bullough, Reference Bullough2019 for a historical account; see Roughgarden, Reference Roughgarden2013 for an evolutionary approach). Cultural changes towards a climate of acceptance of gender and sexual minorities (GSMs) were simultaneously causes and consequences of a wide ranging progress – including in the law (e.g. Ball, Reference Ball2010), as well as in psychiatric and psychological approaches to sexual and gender diversity and related mental health issues (e.g. Drescher, Reference Drescher2015). These changes are currently reflected in a more inclusive social discourse, which requires clinicians to be aware of culturally sensitive terminology in order to improve the effectiveness of their therapeutic communication (see Table 1).

Table 1. Glossary of key terms

GSMs and mental health

Empirical research suggests that, in comparison with non-GSMs, sexual minorities are at higher risk of developing mental health problems (e.g. Plöderl and Tremblay, Reference Plöderl and Tremblay2015), such as generalized anxiety, depression, substance use, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and self-harm (e.g. Chakraborty et al., Reference Chakraborty, McManus, Brugha, Bebbington and King2011), and that transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) individuals have an increased risk of experiencing depression and attempting suicide (e.g. Testa et al., Reference Testa, Michaels, Bliss, Rogers, Balsam and Joiner2017). Also, GSM individuals report lower satisfaction with mental health services (Kidd et al., Reference Kidd, Howison, Pilling, Ross and McKenzie2016), and are more likely to report unmet needs (e.g. untreated depression) than heterosexual and cisgender individuals (Steele et al., Reference Steele, Daley, Curling, Gibson, Green, Williams and Ross2017).

‘Minority stress’ as a conceptual framework for case formulation in CBT with GSMs

Gender and sexual minority stress refers to the unique instances of social stress that GSM individuals encounter directly as a result from having a non-normative sexual orientation (Meyer, Reference Meyer2003), and/or gender identity/expression (Hendricks and Testa, Reference Hendricks and Testa2012). The impact of these unique social stressors on mental health operates at different levels: (1) at a structural level (including: governmental policies – e.g. absence of pro-GSMs political initiatives; systemic discrimination under the law – e.g. absence of same-sex marriage and/or same-sex parenting laws, and of hate crime laws; and cultural norms and institutional political initiatives that constrain the opportunities and access to resources by GSM individuals) (e.g. Ogolsky et al., Reference Ogolsky, Monk, Rice and Oswald2019); (2) at an interpersonal level (e.g. family rejection, school bullying, abuse, and microaggressions such as use of derogatory terms and negative reactions to public display of affection) (Balsam et al., Reference Balsam, Rothblum and Beauchaine2005); and (3) at an individual level (i.e. the internalization of cultural negative messaging and social representations of GSM identities).

Stressors can be distal (i.e. objective stressors that do not depend on subjective perception or appraisal, and thus are unrelated to personal self-identification with the minority status; e.g. hate crimes) and proximal (subjective, individually mediated, related to one self-identifying as part of the minority group; e.g. internalized homophobia) (Meyer, Reference Meyer2015). For example, a woman who is currently in a relationship with another woman may not self-identity as lesbian or bisexual, yet still be discriminated because she is perceived as such (distal stressor). However, a self-identified GSM individual may internalize that prejudice, thus developing a set of generalized unhelpful coping mechanisms (e.g. intimacy avoidance, concealment, isolation) to avoid the anticipated interpersonal discomfort and/or discrimination in social interactions (proximal stressor).

An affirmative psychological approach to GSMs’ mental health benefits from thoroughly considering these structural and interpersonal contexts, as well as cultural and developmental specificities of GSM clients, before leaping into a tailored assessment of individual factors in case formulation.

One paramount milestone that seems to permeate GSMs’ developmental trajectory, and thus should be acknowledged in case formulation with GSM clients, is coming out, i.e. the disclosure of one’s sexual orientation and/or gender identity. As a result from living in societies where heterosexuality and cisgender identity are both the norm and the default assumption, GSM individuals are confronted with the need to come out. Concealing one’s sexual and gender identity results in devastating effects on the mental health and wellbeing of GSMs (Pachankis et al., Reference Pachankis, Jackson, Fetzner, Mahon and Bränström2020b). Because coming out can be either beneficial or problematic, and may have its pros and cons according to an individual’s social context and resources, clinicians should be sensitive to the fact that coming out does not follow a ‘one-size-fits-all’ format. For some clients, coming out is likely to entail family rejection and homelessness (e.g. Puckett et al., Reference Puckett, Woodward, Mereish and Pantalone2015), while for others it may end up in greater resilience and a sense of personal coherence and well-being. Thus, a careful analysis and consideration of the client’s specific context and social circumstances should guide the therapeutic process.

Additionally, therapists should address underlying intrapersonal processes and unhelpful behavioural, and cognitive, emotional and behavioural patterns guiding the decision to conceal one’s sexual and gender identity – such as shame and overall internalized negative self-perceptions for having a GSM identity (e.g. Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Sullivan, Zielonka and Moes2009), as these might be relevant factors in the case formulation of a client’s current mental health difficulties. An in-depth assessment of intrapersonal psychological processes, and their interconnectedness with the overall environment, should be centre stage of a mental health service provision for GSM individuals. These processes may not only provide modifiable aetiological mechanisms of mental health difficulties, but also opportunities for mental health professionals to focus on and promote mindful and compassionate self-care patterns that eventually lead to better mental health and well-being outcomes.

Rejection sensitivity

Parental rejection based on sexual orientation seems to lead to rejection sensitivity (Pachankis et al., Reference Pachankis, Goldfried and Ramrattan2008). Rejection sensitivity should be considered in case formulation of GSMs when the anxiety-fuelled anticipatory expectations of rejection leads to maladaptive coping consequences – e.g. anger and aggression (Baams et al., Reference Baams, Kiekens and Fish2020), and when it leads to avoidance behavior that hinders GSMs’ health – e.g. avoiding healthcare services (Hughto et al., Reference Hughto, Pachankis and Reisner2018).

Stigma

In the context of GSMs, stigma is defined as the societal negative regard and the resulting lack of status and powerlessness of those that do not ascribe to the identities and behaviours associated with heterosexuality and cisnormativity (Mink et al., Reference Mink, Lindley and Weinstein2014). Stigma has three related but distinct domains: (1) anticipated stigma (i.e. concern for being a target of future discrimination); (2) internalized stigma (i.e. a negative self-perception related to one’s GSM identity); and (3) enacted stigma (i.e. the visible external aspect of stigma consisting of episodes of discrimination) (Herek et al., Reference Herek, Gillis and Cogan2009). Enacted stigma seems to lead to reduced health-seeking behaviour (e.g. McCambridge and Consedine, Reference McCambridge and Consedine2014), while internalized stigma is associated with low self-esteem and negative self-evaluation (e.g. Bruce et al., Reference Bruce, Ramirez-Valles and Campbell2008). These relationships seem to be mitigated by ‘outness’ (level of disclosure of sexual and gender identity) (e.g. Whitehead et al., Reference Whitehead, Shaver and Stephenson2016), which highlights the relevance of taking into account the intricate relationship between social stressors (stigma, discrimination), individual decision making (disclosure of one’s sexual and gender identity) and health outcomes.

Internalized homophobia (IH) and internalized transphobia (IT)

IH (i.e. internalized homophobic stigma) has been linked to poor mental health outcomes (e.g. depression, anxiety, fewer social connections, sexual compulsivity, greater concealment) (e.g. Newcomb and Mustanski, Reference Newcomb and Mustanski2010), suggesting that it should be incorporated in case formulation and targeted in therapy. When it comes to IT, TGCN individuals may internalize strict gender norms and expectations (definitions of maleness/femaleness, and manhood/womanhood) that they are unable to meet, which may heighten evaluative self-focus and self-invalidating efforts on passing as cisgender (Bockting et al., Reference Bockting, Coleman, Deutsch, Guillamon, Meyer, Meyer, Reisner, Sevelius and Ettner2016). IT is associated with stigma and psychological distress (Bockting et al., Reference Bockting, Miner, Romine, Dolezal, Robinson, Rosser and Coleman2020), with a higher prevalence of suicide attempts (Perez-Brumer et al., Reference Perez-Brumer, Hatzenbuehler, Oldenburg and Bockting2015), and with anxiety (Scandurra et al., Reference Scandurra, Bochicchio, Amodeo, Esposito, Valerio, Maldonato, Bacchini and Vitelli2018).

Shame

Shame is a social and self-conscious emotion (e.g. Dearing and Tangney, Reference Dearing and Tangney2011), evolutionarily rooted in a threat-focused system that signals potential threats to survival, including social threats such as social rejection. Shame acts as an inner warning of social threat, and triggers a set of submissive and appeasement behaviours (e.g. gaze down, avoid eye contact, hiding, and overall avoidance behaviours) in order to de-escalate conflicts (e.g. Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2003). Shame is cognitively accompanied by a sense of inner defectiveness (e.g. unattractive, worthless, unlovable), is significantly predictive of psychopathological symptoms (e.g. López-Castro et al., Reference López-Castro, Saraiya, Zumberg-Smith and Dambreville2019), and shame experiences can become a central part of autobiographical memory (e.g. Pinto-Gouveia and Matos, Reference Pinto-Gouveia and Matos2011). Shame is a core emotional experience of GSMs (e.g. Matos et al., Reference Matos, Carvalho, Cunha, Galhardo and Sepodes2017; Skinta et al., Reference Skinta, Brandrett, Schenk, Wells and Dilley2014) that should be considered when addressing their mental health, given that its toxicity may generate self-criticism and maladaptive defensive coping strategies (e.g. withdrawal/avoidance, self-concealment).

Intraminority stress

For many sexual minority men [i.e. gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM)], in particular, minority stress is further exacerbated by the stress arising from the gay community itself (i.e. the intraminority gay community stress). This specific type of stress encompasses rigid group norms within the gay community regarding race, masculinity, attractiveness, body type, age, and HIV status. Such perceptions of stress within the gay community are associated with sexual minority men’s mental health concerns and with HIV-risk behaviours (Burton et al., Reference Burton, Clark and Pachankis2020). Moreover, these unique, ranking-based competitive pressures (i.e. being stressed by appraising the gay community’s focus on sex, status, competition, and exclusion of diversity) predict sexual minority men’s mental health over-and-above the typical minority stressors (Pachankis et al., Reference Pachankis, Clark, Burton, Hughto, Bränström and Keene2020a).

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with GSMs

The suitability of the CBT approach

CBT is the most empirically supported psychological approach to psychopathology and mental health, addressing cognitive, emotional, and interpersonal pathways underlying mental health difficulties experienced by many GSM individuals (Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer and Fang2012). Its suitability for targeting pivotal GSM-specific phenomena is rooted in its fundamental tenets (cf. Pachankis, Reference Pachankis2014):

-

(1) CBT is grounded in solid principles of learning and cognition – which makes it highly suited for addressing the relationship between distal and proximal minority stressors and the psychological problems experienced by GSMs (e.g. conditioned fear patterns, and relationship between negative emotional memories and current patterns of interpersonal conflict). Thus, it not only focuses on cognitive processes, but also on contextual/environmental factors – such as social stressors (e.g. microaggressions).

-

(2) CBT directly targets negative self-beliefs and cognitive biases that do not necessarily reflect the ‘truthfulness’ of reality (e.g. internalized homophobia/transphobia, self-stigma, and shame-related thoughts).

-

(3) CBT incorporates and draws on the client’s already existing personal skills, such as GSM-related resilience.

-

(4) CBT is a skills-focused psychological approach that promotes effective ways of addressing both psychological phenomena (e.g. rejection sensitivity, unhelpful worry, internal and external shame) as well as interpersonal contexts (e.g. developing assertiveness, negotiating coming out, coping with episodes of discrimination and social stigma).

-

(5) CBT endorses collaborative empiricism. This may be particularly important when developing a case formulation, as it acknowledges and validates the client’s unique perspective on the problem.

-

(6) CBT does not follow a moralistic approach to behaviour (good versus bad), but rather a functional one (functional versus dysfunctional), which makes it an especially suitable framework for a population that has been historically subjected to moralizing judgements and social put-down.

CBT seems to be an exceptionally useful approach when providing mental healthcare to GSMs, particularly when it comes to addressing the negative thoughts, assumptions and beliefs that underlie problematic and/or unhelpful behaviour. For example, challenging shame-based self-critical thoughts in a supportive and safe therapeutic environment may help decrease internalized homophobic thoughts and rejection sensitivity by recognizing the relationship between one’s cognitions (e.g. ‘I will never have a normal family’) and the resulting problematic behaviour (e.g. withdrawal from social relationships; risky sexual behaviour), and ultimately replacing biased cognition with more balanced views (e.g. ‘every family faces its own challenges’, ‘you can create your own family’). Maladaptive coping strategies (e.g. social isolation) are addressed and more effective coping skills (e.g. talking to a family member or friend who is an ally, and requesting help during coming out) are explored, tested and reinforced throughout therapy (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Austin and Alessi2013). When CBT addresses the restructuring of unhelpful cognitive patterns, it pays great attention to their relationship with emotional responses, problematic behaviour and interpersonal patterns, but also to the role of antecedents and contextual variables (e.g. unsupportive family environments; hostile heterosexist and cisnormative social narratives) (e.g. Newcomb and Mustanski, Reference Newcomb and Mustanski2010). Also, CBT not only tackles unhelpful cognitions and problematic behaviour, but also draws on the client’s existing adaptive coping skills and resources (e.g. resilience) (Herrick et al., Reference Herrick, Stall, Goldhammer, Egan and Mayer2014). Overall, CBT may be a useful tool for empowering GSM clients, by developing effective coping with adverse and/or hostile contexts, and by facilitating flexible, helpful and individual cognitive, emotional and behavioural patterns (Pachankis et al., Reference Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, Rendina, Safren and Parsons2015).

Affirmative CBT with GSMs

GSM-affirmative approaches are client-centred interventions that (1) validate the strengths and experiences of GSM individuals, fostering autonomy and resilience; (2) view same-sex attraction and gender diversity as variations of healthy human experiences – thus acknowledging that same-sex attraction and gender diversity are not inherently pathological, and discarding/rejecting clinical efforts to change these experiences; (3) incorporate knowledge on specific developmental and cultural aspects of having a GSM identity; (4) acknowledge sources of minority stress (e.g. cultural norms, prejudice, discrimination, violence) as core contributors of psychological distress in GSMs, and promotes effective skills to cope with minority-related stressors; and (5) require the clinician to self-examine their personal attitudes towards issues related to the diversity of sexual orientation and gender identities (American Psychological Association, 2012; Pachankis et al., Reference Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, Rendina, Safren and Parsons2015; Singh and Dickey, Reference Singh and Dickey2017). Specifically regarding the affirmation of TGNC clients, it should be noted that an affirmative stance does not imply a preferred outcome, i.e. a push towards a certain gender identity (transgender, cisgender, or otherwise) or presentation, especially when working with children who identify as TGNC (Ehrensaft, Reference Ehrensaft2012). Although gender affirming medical interventions (GAMIs) with TGNC children and adolescents seem to provide psychological benefits (see Mahfouda et al., Reference Mahfouda, Moore, Siafarikas, Hewitt, Ganti, Lin and Zepf2019 for a review), studies on long-term effects are lacking. In addition to abiding by the specific legislation of each country, decisions regarding GAMIs with TGNC children and adolescents should follow international professional guidelines – e.g. the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) standards of care advise a minimum age of 16 years for gender-affirming hormone therapy, and of 18 years for gender-affirming surgery (Coleman et al., Reference Coleman, Bockting, Botzer, Cohen-Kettenis, DeCuypere, Feldman, Fraser, Green, Knudson, Meyer, Monstrey, Adler, Brown, Devor, Ehrbar, Ettner, Eyler, Garofalo, Karasic and Zucker2012), and consider short- versus long-term consequences of GAMIs (e.g. fertility consequences and options when considering pubertal blockade – e.g. see Turban and Ehrensaft, Reference Turban and Ehrensaft2018 for a review on these topics).

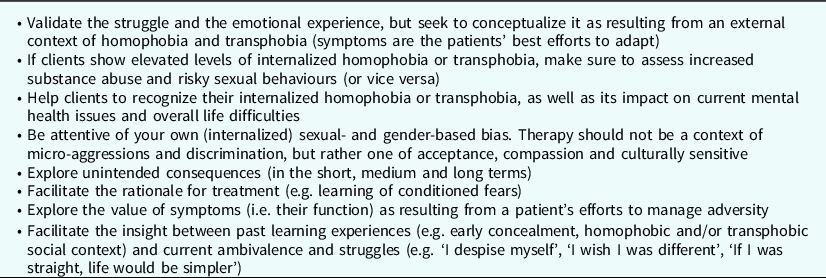

Affirmative approaches to healthcare provision with GSMs result from recognizing the impact of minority stress vulnerability factors on GSMs’ mental illness (Austin and Craig, Reference Austin and Craig2015; Pachankis, Reference Pachankis2014). One of the primary tasks of an affirmative CBT approach is to conduct a thorough assessment on the role that minority stress plays in the aetiology of the client’s mental health challenges. This careful assessment implies not downplaying minority stress (e.g. ignoring it, and strictly focusing on individual cognitive and behavioural patterns) or overemphasizing it (e.g. assuming that pre-disposing or perpetuating factors of a client’s mental health difficulties must be rooted in their sexual and/or gender identities). For some clients, their mental health difficulties might be directly related to their sexual and gender identities (e.g. a trans person who exhibits signs of internalized transphobia and shame for not passing as cisgender) (see Table 2). For others, mental health difficulties might result from an intricate relationship between general and GSM-related issues (e.g. a lesbian who is coping with the impact of a physical chronic illness that requires leave of absence, but whose job security is threatened by a homophobic work manager). For other clients, their mental health difficulties are not related to their GSM status (e.g. a bisexual man who is out and self-accepting, whose sexuality did not contribute to his panic disorder). Indeed, universal factors not directly related to the minority status (e.g. death of a loved one; bankruptcy; unemployment; chronic illness; overall interpersonal conflict) will interact and overlap with minority-related stressors, creating the context upon which general and minority-specific factors operate and lead to mental health problems. It is crucial to ask the client for their own view on how their sexual and gender identity is related to their motivations for seeking mental healthcare, and to periodically revisit this question. This provides the therapist with useful information on the client’s comprehensive heuristic on how minority stress relates to their mental health difficulties, as well as their progress towards affirming their GSM identities.

Table 2. Addressing internalized homophobia or transphobia in CBT

It should be noted that the empirical status of affirmative CBT interventions with GSMs is still lacking overwhelming evidence due to its recency. Studies conducted to date have the limitations of either being uncontrolled (within-subjects designs), of comparing it with passive controls (e.g. waiting list), and/or not following a randomized controlled design (Chaudoir et al., Reference Chaudoir, Wang and Pachankis2017). Nevertheless, existing data point to the benefits of affirmative CBT (Pachankis, Reference Pachankis2018), and suggest the following adaptations (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Austin and Alessi2013; Pachankis, Reference Pachankis2014):

-

(1) Identification and normalization of the negative mental health issues deriving from social minority stress, and discussing how GSM oppression relates to current mental health difficulties.

-

(2) Distinction between problems that result directly from environmental stressors (e.g. microaggressions, discrimination, harassment, violence) and those that are mediated by individual cognitive and behavioural patterns, and unhelpful coping mechanisms (e.g. social isolation; rejection sensitivity).

-

(3) Validation of clients’ self-reports of GSM-related discrimination, instead of automatically reframing it as a universal experience (e.g. ‘we all are treated unfairly sometimes’) or engaging in reappraisal efforts (e.g. ‘maybe that person did not mean to use that word as an insult, maybe he calls everyone queer’). For example, therapists targeting rejection sensitivity should convey empathic validation, emotional resonance, and remain aware that GSMs do in fact experience objective instances of rejection, thus pointing to a redirection of the therapeutic focus from distortions to their impact (e.g. Meyer, Reference Meyer2020).

-

(4) When using cognitive restructuring, address the ‘helpfulness’ of a thought and belief, rather than its ‘truthfulness’ (e.g. ‘is it helpful to guide your decision of coming out by the thought that some of your colleagues will reject you?’). Therapists may discuss the pros (benefits) and cons (costs) of intentionally endorsing negative GSM-related negative thoughts and beliefs.

-

(5) Help cultivate assertiveness in order for clients to communicate openly their own needs, to fight for their personal interests when facing social difficulties and instances of discrimination and abuse, and to refuse engaging in unwanted sexual activities and/or in health risky behaviours.

-

(6) For GSM clients that live in unsafe contexts, help identify threats to safety and develop a contingency plan (i.e. contingency management and crisis intervention).

-

(7) Assessment and activation of the social support network: family of origin or family of choice, peer support (e.g. friends) or formal support (e.g. LGBT+ associations, shelters for GSM youth, gay–straight alliances).

-

(8) Strengthen the engagement with the GSM community to cultivate social connectedness, and decrease isolation. The GSM community offers a proximal context where irrational thoughts, assumptions and beliefs may be tested through guided conduction of behavioural experiment.

-

(9) Affirmation of GSM identities by co-creating a list of positive feelings around having a GSM identity, namely by stressing out the resilience, strength and courage necessary to face social adversities, and cultivating self-affirmation and pride by contextualizing struggles in a much larger history of GSM individuals who overcame obstacles (i.e. GSM shared humanity). Include homework assignments for the client to search for historical, cultural, sports-related, and political figures who made a difference by coming out, and learn about their motivation to come out.

-

(10) When suggesting homework assignments that promote GSM affirmation, these should be congruent with GSM culture and stage of coming out process – a person who is not out may not feel comfortable in attending a LGBT+ Pride Parade or gathering, but may be willing to watch a LGBT+ themed movie or series.

Regarding duration and number of sessions, due to the complex interconnectedness of vulnerability and maintenance factors that can be GSM specific (e.g. distal and proximal minority stressors) and GSM non-specific, CBT with GSMs might benefit from longer sessions and protocols. Although this needs further empirical evidence, mental health providers of group affirmative CBT with GSMs have suggested that 90 minutes per session would be recommended in order for clients to be able to process their experiences, especially in a group format (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Ruiz Rosado and Chapman2019), with preliminary evidence of the benefits of a weekly-base delivery (Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, Rimes and Hambrook2021).

One example of an affirmative CBT programme addressing health risks of gay and bisexual men is the Effective Skills to Empower Effective Men (ESTEEM) programme (Pachankis, Reference Pachankis2014). ESTEEM is a 10-session programme that addresses the minority stress pathways (i.e. rejection expectations, internalized homophobia, concealment, rumination, unassertiveness, and impulsivity) that have been empirically linked to mental health problems and risky sexual behaviours (see Table 3). ESTEEM was found to be effective in reducing depressive symptoms and alcohol use problems, and in increasing healthy behaviours (e.g. condom use) in a sample of young gay and bisexual men (Pachankis et al., Reference Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, Rendina, Safren and Parsons2015).

Table 3. Dimensions of the ESTEEM intervention

Regarding TGNC individuals, it is especially important for mental health professionals to embody an affirmative clinical posture that acknowledges the vast diversity of gender identity and expression as valid and healthy in itself (Austin and Craig, Reference Austin and Craig2015). Clinicians are thus encouraged to assess their own gender-based biases, such as those related to prejudice against other gender identities and expressions that do not ascribe to a binary cisnormative notion of gender, which may result in a pathologizing stance towards gender fluidity. It is especially important for therapists to self-reflect on personal beliefs of gender when working with TGNC clients, in order to prevent uninformed attitudes that perpetuate stigma and the client’s related difficulties. Furthermore, the decision to and the extent of transitioning should not only be based on medical and technical criteria, but most of all on the client’s self-determination and intrinsic motivation. Therefore, an affirming therapist should be aware that TGNC individuals may not see their gender identity through the perspective of medical transition. In addition to assessing trans-specific sources of stress and their impact on self-identity (see Table 4), affirmative CBT with TGNC individuals might include different strategies (Austin and Craig, Reference Austin and Craig2015):

-

Psychoeducation: therapists can help TGNC clients recognize the relationship between past traumatic experiences of transphobia and overall negative messages towards TGNC individuals, self-beliefs, internalized transphobia and shame, and current mental health challenges. Therapists should validate the emotional experience following the traumatic event and the in-session recalling of the event. These are opportunities to help clients move away from self-critical beliefs and negative social comparison, and develop a compassionate and empathic narrative of the self as someone who is navigating a difficult experience through potentially traumatic circumstances.

-

Cognitive restructuring: therapists may engage in Socratic dialogue aimed at developing more balanced views, by questioning beliefs anchored in social prejudice, and encouraging the client’s self-determined thought and action (Carona et al., Reference Carona, Handford and Fonseca2020). As an example, when addressing cisnormative beliefs of gender, therapists might question ‘what does it mean to be “a real man” or “a real woman”?’, and follow up the questioning to arrive at a place where ‘gender’ is not exclusively or primarily defined by body parts (e.g. ‘if a cisgender woman gets a mastectomy as a result of breast cancer, is she less of a woman?’; ‘what if a cisgender man loses his genitalia as a result of cancer?’). Therapists may also promote cognitive dissonance, by providing comments and reflections that aim to challenge the consistency and coherence of the belief. In cases where patients struggle with emotionally intense memories of traumatic events and/or post-traumatic stress symptoms, engaging in imagery rescripting might help reduce the vividness of the event, as well as reduce the associated feelings of shame and guilt, through a three-phase imagery procedure that aims to create an environment where the adult client takes care of their younger self who experienced the trauma (see Arntz and Weertman, Reference Arntz and Weertman1999 for a detailed description of imagery rescripting).

-

Behavioural activation: after clarifying and listing the patient’s values and goals, and ascertaining/exploring their links with avoidance patterns of behaviour that have been moving the client away from those same goals, therapists may help TGNC clients engage in previously avoided trans-affirming activities (e.g. gathering with trans-affirming friends; visiting and volunteering in trans support organizations – therapists should help clients choose organizations that have been duly scrutinized for safety, and with a known reputation and recognition by official governmental entities; watch trans-inclusive movies and TV shows; participating in trans visibility marches), thus decreasing social isolation, and promoting a sense of accomplishment, self-agency and self-advocacy, which may in turn buffer depression and anxiety.

Table 4. Trans-affirmative assessment of transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) identity and minority stress

Adapted from Austin et al. (Reference Austin, Craig and Alessi2016)

Reprinted from Psychiatric Clinics of North America, volume 40(1), Ashley Austin, Shelley L. Craig & Edward J. Alessi, Affirmative Cognitive Behavior Therapy with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Adults, 141–156. Copyright (2017), with permission from Elsevier.

Boosting affirmation: a strengths-based affirmative CBT

In addition to focusing on the modification of detrimental psychological processes and reduction of psychopathological symptoms, CBT has been adapted to promote positive attributes (Padesky and Mooney, Reference Padesky and Mooney2012). This is in line with broader conceptions of mental health, which postulate that complete mental health does not equate to the absence of mental illness, but also includes a distinctive dimension of flourishing (Keyes and Brim, Reference Keyes and Brim2002). Promoting resilience and/or bringing resilient-related strengths to the therapeutic work may be useful when conducting CBT with GSMs, helping them to navigate and overcome minority-related social stress (Meyer, Reference Meyer2015).

Strength-based CBT adds a much-needed positive-focused layer for addressing mental health of GSMs, by providing a theoretically solid and CBT coherent four-step framework to fostering resilience (Padesky and Mooney, Reference Padesky and Mooney2012): (1) searching for strengths (these are individual attributes – e.g. good health, easy temperament, interpersonal skills, cognitive skills and intelligence, emotion regulation skills, willingness and opportunity to help others, a sense of connection to others); (2) construction of a personal model of resilience (PMR) (co-created and based on the client’s strengths and on specific strategies that are listed by the client – e.g. if one strength is ‘commitment to helping others’, the strategy might be ‘volunteer in an LGBT centre’); (3) application of the PMR (potentially generalizing resilient-related skills from one area into another where the client might be struggling – e.g. committing to engage in self-care actions when struggling with difficult emotions); (4) practising resilience (co-creating a behavioural experiment where the client plans a situation, predicts reactions, and practises the listed strengths) (see Fig. 1). A strength-based CBT may be especially helpful to GSMs due to its inherently positive framework: a focus on individual strengths may boost the standard affirmative CBT approach (which focuses on general social minority vulnerability factors) (see Table 5).

Figure 1. Four steps of resilience (Padesky and Mooney, Reference Padesky and Mooney2012). Reproduced with permission from the copyright holder (2021).

Table 5. Fictional case vignette: Dave’s personal model of resilience (PMR)

Developing courage: a focus on assertiveness training

Assertiveness is defined in literature as the ability to act accordingly to personal interests, which includes affirming one’s rights and standing up for oneself (Alberti and Emmons, Reference Alberti and Emmons2017). Affirmative CBT interventions with GSM individuals may benefit from including assertiveness training, given that GSM unassertiveness seems to be rooted in minority stress (Pachankis et al., Reference Pachankis, Goldfried and Ramrattan2008), and to have a negative impact on health-related behaviours, such as condom usage (Hart and Heimberg, Reference Hart and Heimberg2005). Sexual assertiveness seems to be an important health-protecting skill, as it encompasses the ability to refuse unwanted intercourse, to commit to using appropriate protection, and discussing sexual history with current partner(s) (Loshek and Terrell, Reference Loshek and Terrell2015). Assertiveness training might increase the client’s ability to establish and communicate appropriate boundaries to others. It should be stressed that part of assertiveness training is also learning to recognize when it is safe to act assertively.

Overall, assertiveness training promotes GSMs’ sense of agency and control in minority stress environments (Pachankis, Reference Pachankis2014), for example acting assertively when overhearing a prejudiced comment or a discriminatory situation, forming healthier relationships, and refusing substance misuse or unwanted sex. Assertiveness training might include providing information on social skills and on how to act in specific situations, discussing video and audio recordings of the client, and role-playing of interpersonal assertive interactions (Speed et al., Reference Speed, Goldstein and Goldfried2018). Targeting assertive behaviour also serves a purpose of exposure, given that clients are confronted with interpersonal fears (e.g. fear of rejection, discrimination, conflict). In assertiveness training, the therapist is not only attentive to the client’s unassertive behaviour, but also encourages assertiveness in sessions, and creates behavioural assignments outside a session that promote assertive behaviour.

Assertiveness goes hand-in-hand with courage. In many instances, in-session work focuses on navigating discriminatory and/or abusive situations derived from being a GSM. Therapy promotes self-affirming skills that necessarily require courage-guided assertiveness (Ruff et al., Reference Ruff, Smoyer and Breny2019). Acting assertively takes courage: it implies the acknowledgement of feared obstacles, the recruitment of personal resources, and taking proper action. An affirmative CBT therapy addressing courage may ask the client to list past situations where they acted courageously, stressing the fear, purpose and action components of courage in those situations, thus creating a ‘courageous inventory’. Also, therapists may use in-session observational learning as a route for modelling courageous action by watching videos and movie scenes where GSM characters act courageously, and then discussing with the client their self-efficacy in acting similarly, anticipating possible obstacles, and how to overcome them. Courage essentially results from choosing growth over safety. This means that courage exists in the intersection between fear, purpose and action (Goud, Reference Goud2005). For example, a GSM individual may be struggling with coming out due to the anticipation of family rejection and/or discrimination (fear), but nonetheless are committed to living a meaningful life (purpose), thus choosing to come out to their family (action).

Developing courage implies a process of ‘toughening’ (Smith and Gray, Reference Smith and Gray2009), which therapists may shape/cultivate by encouraging and reminding the client that they already possess and have exhibited such strengths and potentials in many difficult situations. It also entails willingness to experience the difficult thoughts and emotions that accompany a courageously assertive action (e.g. fear of rejection; self-doubt; overall anxiety). The affirmative therapist should encourage clients by cheering and motivating them (i.e. genuinely praising the efforts of the client, and reminding them of their potential), promoting a sense of belonging and hope. For some GSM clients, courage may imply the acknowledgment of personal characteristics previously perceived as shameful, and avoided as such (Bratt et al., Reference Bratt, Gralberg, Svensson and Rusner2020). Therefore, assertiveness training and courage development through affirmative CBT may benefit from including techniques that promote awareness, willingness and self-compassion.

New trends in CBT with GSMs: incorporating mindfulness and compassionate skills

Within the tradition of CBT, new perspectives and techniques have emerged over the last thirty years (Hayes and Hofmann, Reference Hayes and Hofmann2017). Two features seem to be clearly distinctive: (1) a paradigm development, where the focus of therapy is not on changing the content of internal unpleasant experience, but on changing its function and context, and using tools that promote willingness and openness, instead of modification and control; and (2) targeting self-to-self relating skills previously thought as secondary tacit outcomes of therapy (acceptance, distancing/decentering, compassion), with explicit procedures and practices.

Mindfulness in therapy

Mindfulness is perhaps the common thread of these new approaches, which can either be strictly mindfulness-based, incorporate mindfulness in broader behaviourally oriented approaches, or use mindfulness as a facilitating tool for developing other skills such as self-compassion. In the context of mental health provision with GSM individuals, mindfulness seems to be a useful adjunct to affirmative therapy by promoting awareness and acceptance self-regulatory skills (Skinta and Curtin, Reference Skinta and Curtin2016).

Mindfulness entails the ability to pay attention to the ongoing experience on purpose, in the present moment, and without judgement (Kabat-Zinn, Reference Kabat-Zinn2003). Dispositional mindfulness may be regarded as a protective individual trait against psychopathological symptoms (Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Yousaf, Vittersø and Jones2018), and its positive impact on mental health seems to occur through specific psychological mechanisms (Shapiro et al., Reference Shapiro, Carlson, Astin and Freedman2006), including reperceiving, decentring from and acceptance of negative thoughts (e.g. internalized homophobic rumination) and difficult emotions (e.g. shame), which makes it a useful approach to help GSM clients (Cheng, Reference Cheng2018) (see Table 6). Promoting mindfulness skills may reduce the impact of perceived discriminatory events on depressive symptoms in GSMs (e.g. Shallcross & Spruill, Reference Shallcross and Spruill2018).

Table 6. Three-minute breathing space practice

Mindfulness promotes acceptance coping skills that seem to be protective against the impact of minority stress on depression (Bergfeld and Chiu, Reference Bergfeld and Chiu2017), which is perhaps particularly relevant, considering that many risky and health-damaging behaviours (e.g. substance use; sexual encounters without use of condom) might serve an avoidance function (negatively reinforced by the short-term consequence of distress alleviation) (e.g. Felner et al., Reference Felner, Wisdom, Williams, Katuska, Haley, Jun and Corliss2020). Mindfulness-based interventions were found to effectively reduce depression, avoidance, the impact of traumatic events, and minority-related stress (Tree and Patterson, Reference Tree and Patterson2019).

Compassionate perspective

Compassion is defined as a sensitivity to the suffering of others and of the self, accompanied by a strong commitment to alleviate and prevent it (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2014). There are three different ‘flows’ of compassion: we can be compassionate towards others, experience the compassion of others towards ourselves, and/or self-direct compassion to ourselves (i.e. self-compassion). Self-compassion has been a topic of interest in mental health research due to its buffering effects on psychopathological symptoms (Macbeth and Gumley, Reference Macbeth and Gumley2012), and positive impact on wellbeing (Zessin et al., Reference Zessin, Dickhäuser and Garbade2015). Promoting self-compassion seems to be a relevant goal in an affirmative mental healthcare with GSMs, as it entails cultivating a self-kind and non-judgemental attitude towards perceived personal failures, inadequacies and differences (e.g. internalized stigma, homophobia and transphobia), a present-moment awareness of ongoing internal experiences (e.g. anticipation of social rejection; ruminative thinking), and a recognition that suffering is part of the human condition (e.g. common humanity, including other GSMs who also experience similar feelings of inadequacy, and go through potentially traumatic social stress situations). There are many strategies to cultivate compassionate feelings, and Loving-Kindness meditation is one that can be easily adapted to GSMs specificities (see Table 7). Also, compassionate breaks might be incorporated not only into therapy, but also into clients’ daily lives, in which the client briefly pauses (3 minutes), acknowledges the present moment of difficulty or suffering (e.g. the clients might say to themselves ‘this hurts’, ‘this is a difficult moment’), recognizes that suffering is part of the human condition, thus connects them with others (e.g. clients might mentally say to themselves ‘I am not alone experiencing this; other people are suffering just as I am right now’), and respond to their suffering with warmth and kindness (e.g. clients might begin to ask ‘what do I need right now to be self-kind?’, and say to themselves ‘may I learn to accept myself as I am’, ‘may I give myself the compassion I need right now’).

Table 7. Brief loving-kindness meditation adapted to GSM clients with internalized stigma

Although in their infancy, there have been promising efforts into developing compassion-based interventions with GSMs, which are expected to be thoroughly examined in a near future and upcoming years (Finlay-Jones et al., Reference Finlay-Jones, Strauss, Perry, Waters, Gilbey, Windred, Murdoch, Pugh, Ohan and Lin2021; Pepping et al., Reference Pepping, Lyons, McNair, Kirby, Petrocchi and Gilbert2017).

Conclusions

GSMs present an increased risk of developing serious mental health problems (including generalized anxiety, depression, substance abuse, obsessive-compulsive disorders, self-harm, and suicide attempts). This increased risk results from a complex interplay between general and GSM-specific factors, where heightened social stress resulting from prejudice, discrimination and harassment is a core factor of vulnerability. Additionally, GSM individuals are less likely to search for mental healthcare, and present low satisfaction with healthcare services. Affirmative CBT interventions with GSMs incorporate useful tools for clinicians to address GSMs’ mental health challenges. First, inclusive language and up-to-date terminology contributes to the development and maintenance of a sound therapeutic relationship. Second, sexual and gender development milestones (e.g. coming out) and processes (e.g. rejection sensitivity, stigma, internalized homo-transphobia, shame) should be taken into consideration. Carefully assessing the configuration of symptoms and difficulties is an essential feature of the intervention plan. Third, clinicians should identify the gender- and sexual-related difficulties that arise from cisheteronormative social prescriptions, and not exclusively conceptualize the client’s difficulties as a result of internal processes. Taken altogether, validating self-reports of GSM-related discrimination, deconstructing self-prejudices, cultivating and reinforcing strengths (e.g. assertiveness, resilience, safeness, community connectedness and social support), and balancing pros and cons of coming out should be core targets of therapy. Research on recent CBT approaches (e.g. mindfulness, self-compassion) has identified promising protective factors (e.g. reperceiving, decentring from and acceptance of negative thoughts) against mental health problems. These new tools, along with a mindful and non-judgemental attitude from the therapist, may increase GSMs’ seeking of mental healthcare services, as well as the sense of social safeness, thus helping GSMs to develop an affirmative and accepting relationship with their inner experience and identities.

Key practice points

-

(1) GSM individuals face additional mental health challenges related to the social stress of navigating cisheteronormative contexts, which should be incorporated in case conceptualization and intervention.

-

(2) Cognitive behavioural therapists should be cognizant of a culturally sensitive clinical discourse when working with GSM clients.

-

(3) CBT is a suitable psychological approach to increase the mental health of GSMs, and its tenets are capable of coherently incorporating a strengths-based approach and an affirmative stance to the diversity of sexual orientation and gender identities of clients.

-

(4) Recent developments in CBT (e.g. mindfulness and compassion-based interventions) provide additional tools for improving the effectiveness of CBT approaches in empowering GSM individuals.

Acknowledgements

Carlos Carona (C.C.) is especially grateful to Prof. Dr. Cristina Canavarro and Dr. Ana Fonseca, for their encouragement and support; to Prof. Dr. Ana Paula Matos, for her continuing clinical supervision in CBT; and to Paula Atanázio and Dave Llanos, for the thought-provoking discussions that firstly motivated the writing of this article.

Financial support

S.C., C.C., D.R., C.S. and P.C. are supported by the Center for Research in Neuropsychology and Cognitive Behavioral Intervention (CINEICC; Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, University of Coimbra) (UID/PSI/00730/2020). D.S. is supported by a PhD scholarship funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) (SFRH/BD/143437/2019).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Ethics statements

When writing the current manuscript, the authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies, and by the British Psychological Society. Due to the theoretical nature of the current manuscript, ethical approval was not required.

Author contributions

Sérgio A. Carvalho: Conceptualization (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Drafting the manuscript (lead); Paula Castilho: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal); Daniel Seabra: Formal analysis (equal), Investigation (equal); Céu Salvador: Formal analysis (supporting); Daniel Rijo: Formal analysis (supporting); Carlos Carona: Conceptualization (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (equal), Drafting the manuscript (lead).

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.