I think, then, that Negroes must concern themselves with every single means of struggle: legal, illegal, passive, active, violent and non-violent. That they must harass, debate, petition, give money to court struggles, sit-in, lie-down, strike, boycott, sing hymns, pray on steps—and shoot from their windows when the racists come cruising through their communities.

—Lorraine Hansberry (1962)Footnote 1In the fall of 1925, W. E. B. DuBois was fed up. Black Americans had been moving out of the South in large numbers, and the segregated neighborhoods they were forced to move into when they arrived in northern and western cities were overcrowded, overpoliced, and underserved. As more and more Black families transgressed the residential color line simply looking for space to live, white people in those neighborhoods responded with violence. In the pages of The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP, DuBois identified the racism inherent in the structural apparatuses that supported white housing while demonizing Black residents who wanted better places to live:

Dear God! Must we not live? And if we live may we not live somewhere? And when a whole city full of white folk led and helped by banks, Chambers of Commerce, mortgage companies and “realtors” are combing the earth for every decent bit of residential property for whites, where in the name of God can we live and live decently if not by these same whites?Footnote 2

DuBois's frustration was a result of several recent cases in which Black families had moved into white areas of Detroit, only to be violently attacked and driven out. Two events in particular had grabbed his attention. The first was an attack on Alexander Turner, a Black doctor who had long served white patients and lived in a white area of town. When Dr. Turner purchased a new house in a nearby white neighborhood, he was unconcerned about retaliation; he had lived and worked among white people in Detroit without any problem. On the day he and his wife moved into their new home, however, they were confronted with a crowd of thousands of white people who began throwing stones at the Black painters the Turners had hired to work on the house. Then, the violence escalated. People in the crowd started throwing rocks at the house, smashing windows and surging toward the home. The Turners had no choice but to barricade themselves inside. The attack was in full swing when they heard a knock on the door. The men at the door identified themselves as emissaries from the mayor who had sent them to protect the Turners. Dr. Turner opened the door, and dozens of attackers swarmed into the house. While some of the intruders ransacked the place, men who said they were representatives of the Tireman Avenue Improvement Association took Dr. Turner hostage and demanded he sign the deed of the house over to them. Turner, desperate and fearing for his and his wife's lives, agreed to sign the papers. The police officers who had watched the whole invasion take place then stepped in, allowing the Turners to leave. As the Turners drove away, the mob attacked their car. Finally, they made it out, called a lawyer, and signed away their new house to the representatives of the mob that had plundered it.Footnote 3

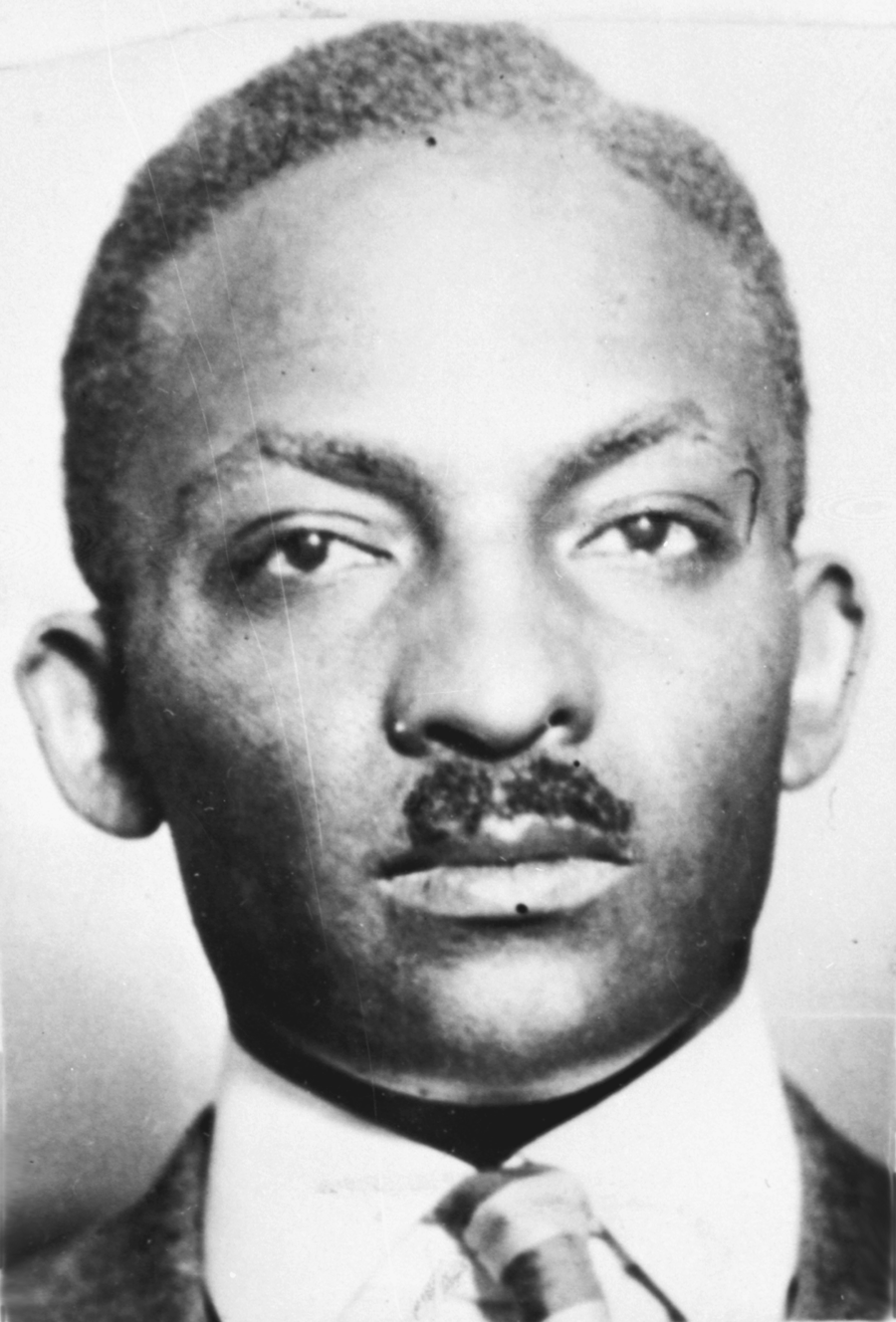

The second event happened in the fall, when another Black doctor, Ossian Sweet, moved into a house he had purchased in a white neighborhood on the other side of town (Fig. 1). In between the time when the Turners were forced out of their home and the Sweets moved into theirs, several other Black families were attacked by white mobs when they moved into white areas. The Sweets were wary when they arrived at their new house; along with their other possessions, Ossian moved a gunnysack full of guns and ammunition in on the first day. When alerted to an upcoming organized attack on the home, Ossian and his wife, Gladys, made plans for their own defense (Figs. 2, 3). Ossian had heard the stories of Dr. Turner, forced to cower in his own home, which was then stolen from him on threat of death. Ossian had decided that his inevitable encounter with enraged white neighbors would not end the same way. He asked nine men—two of his brothers, four close friends, and three mere acquaintances—to come to his house that night and help him defend it. As the gathering crowd closed in on the Sweet home, several people inside shot from the windows of the home into the crowd assembled outside. One white man was killed and another injured in the shooting; all eleven of those inside the house were charged with murder. A joint trial was scheduled to begin in November.

Figure 1. The Sweets’ home at 2905 Garland Avenue, Detroit, Michigan. Photo: Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

Figure 2. Dr. Ossian Sweet. Photo: Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

Figure 3. Gladys Sweet. Photo: Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

DuBois, for his part, made the connection between the housing crisis and the need for Black armed self-defense plain: if government officials weren't going to protect Black Americans from their white neighbors, then Black people were well within their rights to take up arms in their own defense. In fact, he argued, it was inevitable that they would do so:

If some of the horror-struck and law-worshipping white leaders of Detroit instead of winking at the Ku Klux Klan and admonishing the Negroes to allow themselves to be kicked and killed with impunity—if these would finance and administer a decent scheme of housing relief for Negroes it would not be necessary for us to kill white mob leaders in order to live in peace and decency. These whited sepulchres pulled that trigger and not the man that held the gun.Footnote 4

DuBois and others compared Dr. Turner's response to white violence to Dr. Sweet's, lionizing Sweet's response while excoriating Turner's. “The dirty coward got down on [the] floor of his car and made his chauffeur drive thru the mob,” said one person. “He knew when he moved in he was going to have trouble and he should have gone prepared to stay or die.”Footnote 5 DuBois was gentler, but nevertheless disappointed in Turner: “He moved in,” DuBois wrote. “A mob of thousands appeared. . . . He gave up his home, made no resistance, moved back whence he came, filed no protest, made no public complaint.”Footnote 6 DuBois recognized the double bind, however; Ossian, Gladys, and their allies may have bravely defended their home, but now all eleven were in jail, awaiting trial on charges of conspiracy and first-degree murder.

In this essay, I examine the spectacular performances of armed home defense and legal self-fashioning that Ossian Sweet enacted, focusing specifically on what this case can reveal about Black challenges to legal and extralegal violence during Jim Crow. I argue that Sweet's performances are acts of tactical lawfulness—theatrical attempts by those who are absented from the centers of legal and juridical production to resist the processes of racialized inscription imposed by that production. This is enacted through the employment of legal “guileful ruse[s],” or the performance of using the text of the law against itself.Footnote 7 Ossian Sweet, by planning and executing the armed defense of his home and then enacting his own race psychology at trial, laid claim to the citizenship rights that were his in the text of law, if not in the practice of it, challenging the legal system in Detroit to live up to the promises encoded in its own documents. During his trial, Sweet appealed to the “sacred ancient” right of men to defend their homes and families and positioned himself as a metonymic representation of all Black Americans who were fighting for the right to live where they pleased.Footnote 8 His performance of tactical lawfulness took the law at its word by insisting on a nonracist application of legally guaranteed rights—particularly the masculine right to own property and protect his “castle” from outside intrusion—both of which are expressions not only of citizenship, but also of civic identity and social belonging.Footnote 9 With help from the NAACP, Sweet mounted a radical defense of his humanity not by ignoring his racialized identity, but by publicly, and theatrically, reaffirming it by using firearms to defend his home, centering his Blackness at trial, and retelling the story of his home defense and trial at gatherings throughout the United States following his successful legal defense.

Performing Tactical Lawfulness

Tactical lawfulness describes the ways that marginalized groups within the nation-state use the text of the law against itself by performing strict legality in the face of legal and extralegal oppression. For this formulation, I expand on Michel de Certeau's articulation of the difference between strategies, or the means by which an entity with “will and power” marks out, controls, and polices its space, and tactics, or the fluid, responsive ways in which those who are positioned outside of and subjugated by formal structures of power respond to those strategies.Footnote 10 Black Americans living under the brutal regimes of Jim Crow America staged acts of tactical lawfulness in many ways, including daring performances of home defense, passionate oral defenses of citizenship rights, and carefully executed lawsuits. These acts embedded radical critiques of the white supremacist state within overtly legal performances of gun ownership, self-defensive violence, and juridical remedy in order to demand redress for the civic estrangement of Black Americans.

De Certeau's theory of tactics and strategies is one of power—how power is marshaled, preserved, and mobilized. He was thinking through alterity in the wake of colonial revolution, and his systemic analysis of everyday life represents an attempt to theorize from the margins and within systems of oppression. As a result (and in contradiction to Michel Foucault's totalizing view of power), he developed a theory of flexible, mobile resistance—not necessarily a means to escape structures of power, but one by which people challenge that power every day. Within the heuristic of strategies and tactics, he defines a strategy as “the calculation (or manipulation) of power relationships that becomes possible as soon as a subject with will and power (a business, an army, a city, a scientific institution) can be isolated.”Footnote 11 Once that subject is delineated, it marks out a space from which to operate and the means by which to control the subjects that fall within its purview.

A tactic, on the other hand, exists both in contrast to and in conversation with strategies. While resisting strategies meant to contain and produce compliant subjects, a tactic represents the possibility and inevitability of resistance within a system of subjectivization. De Certeau describes a tactic as “a calculated action determined by the absence of a proper locus. . . . The space of a tactic is the space of the other. Thus it must play on and with a terrain imposed on it and organized by the law of a foreign power.”Footnote 12 While a strategy is typified by the space it possesses and from which it operates, a tactic is typified by its condition of being “nowhere,” or always operating within the field of the “enemy” rather than from its own space.Footnote 13 Thus, people who are forced into utilizing tactics are those who must account for the terrain of power and shape their responses within and against it. Tactics utilize the space of power against itself. By doing so, they divert from the power of the central authority and reveal the fissures that are always present in strategic control.

By their nature, tactics are mobile, fleeting, ephemeral, and opportunistic—making them close kin to theatre and performance. Indeed, the practices of tactical lawfulness, of using the legal system against itself, are theatrical ones. I here use Rebecca Schneider's observation that what makes something theatrical is the “matter of (re)production,” of being “staged, enacted, reenacted.”Footnote 14 Tactical lawfulness, like the common law on which it is based, gains its power by virtue of public, visible repetition and citationality. Common law, often placed in opposition to statutory law, is legal doctrine that is established through precedent made by judges when they rule on a case. Usually, this requires judges to reference and build upon past precedent; thus, common law often works to reproduce and revivify past legal decisions as well as the structures that underpin those decisions. Common law, in this formation, is a strategy used to maintain power. Tactical lawfulness also reproduces legal doctrine, but instead of reproducing those structures that underpin the law, it offers a challenge to those structures by emplacing an unexpected body at the center of the law's protection. This repetition of the law with a difference can pull back the strategic curtain that hides the law's constructed nature, revealing the sedimented ideologies that the law is protecting. Acts of tactical lawfulness that are staged, enacted, and reenacted by oppressed people who are absented from the law's protection, not by statute but by custom, can force a reckoning with the strategies that perpetuate white supremacy within the law, even if the acts alone cannot eradicate those strategies.

Throughout US history, Black people have been absented from the law's protection both by statute and by custom, or what Saidiya Hartman describes as “the acquiescence of the law to sentiment, affinity, and natural distinctions.”Footnote 15 One area in which this is clear is the right to bear arms in self-defense. While there has been much wrangling over the meaning of the text of the Second Amendment, a common-law right to self-defense is much less controversial. The right to own and use a gun in self-defense, however, has often been textually limited to white men and has even more often been practically limited to them.Footnote 16 Even when the law is textually neutral on gun ownership and self-defense, a Black man carrying, brandishing, or using a gun in self-defense is an act of tactical lawfulness. He is assuming the role of full citizen entitled to the protection of the law, even if the law-as-performed hasn't applied to him in the past. This repetition with a difference, of layering a role on a body that has not been permitted to assume that role in the past, is evidence of the inherent theatricality of tactical lawfulness.

During the Jim Crow era, Black Americans used acts of tactical lawfulness to resist the processes of racialized inscription imposed by the legal and juridical production that perpetuated white supremacy. Strategies of law enshrine legal power within the ritual spaces of production, including neighborhoods, courtrooms, and jails, in order to wrap the production of legality in the robes of authority and to occlude its constructed nature. These processes appear “natural” by virtue of their ensconcement in a space and their inscrutable origins in past law. The very basis of common law is its ability to crystallize the arbitrary decisions of the past into something that resembles an intentional shape.Footnote 17 The juridical, penal, and carceral structures I discuss in this essay all capitalize on the ability to produce legal reality by maintaining control over the spaces of judgment and punishment. Practices of tactical lawfulness—such as bearing and using a weapon when it is legal to do so, or buying a house in a segregated area—meet the law on the street and in the court, and on the law's own terms, in order to reveal its partiality, challenge its inherent biases, and dismantle its hold on racialized communities. Although many popular conceptions of Black American freedom movements in the twentieth century place nonviolent resistance and self-defense in opposition, thinking about political resistance as tactical lawfulness challenges that binary and demonstrates how, for Black Americans in the twentieth century, armed self-defense and nonviolent resistance, including using the courtroom to stage challenges to legal racism, were coconstitutive.

Performing Self-Defense in the Jim Crow North

By the time that Ossian Sweet was born in Bartow, Florida, to Henry and Dora Sweet in 1895, the promises of emancipation and Reconstruction had almost fully evaporated, displaced by Redemption politics that had returned the state—and the South as a whole—to a white supremacist status quo within a few years after US forces withdrew in 1877. In 1889, Florida became the first state to institute a poll tax; within one year after the institution of the tax, voter registration had tumbled by 50 percent. By the turn of the twentieth century, the disenfranchisement of Black voters in Florida was complete, as interlocking systems of Black voter suppression including literacy tests, white primaries, poll taxes, grandfather clauses, and residency requirements shrunk the number of Black voters to effectively zero.Footnote 18 In Bartow, schools and other public services were segregated and the color line policed harshly. Black residents of Bartow were locked out of more lucrative professions, limited instead to farming, logging, and working in the dangerous phosphate mines.Footnote 19 Anti-Black terrorism, which had hastened the collapse of Reconstruction throughout the South, continued to stalk Black citizens; in Bartow alone, white residents lynched at least six Black men between 1899 and 1901.Footnote 20

Throughout US history, enslaved and free Black Americans have armed themselves with guns against multiple manifestations of racial terror in the United States, including enslavers, slave patrols, lynch mobs, and police forces—whether or not it was legal.Footnote 21 Prior to Reconstruction, these acts of self-defense (both owning and using a gun for protection) were done largely in private since Black Americans were often legally prohibited from owning firearms, but in the war's aftermath, radical Republicans argued that the right to keep and bear arms was integral to the safety and success of newly freed Black Americans.Footnote 22 This impetus toward ensuring the rights of citizenship for Black Americans was reflected in Reconstruction's legal texts, like the Freedmen's Bureau Act, passed by Congress in 1866, which declared that newly freed Black Americans were entitled to “full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings concerning personal liberty . . . including the constitutional right to bear arms,”Footnote 23 and the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed equal protection under the law. These moves gave Black Americans cause to hope that, through enforcement by federal troops and statutes that prevented former Confederate leaders from assuming positions of power, the text of the Reconstruction-era laws and amendments would represent an actual, embodied change in their daily, lived experience.Footnote 24 During the era of Southern Redemption, however, the dissolution of policies intended to protect newly enfranchised Black Americans and the dilution of the Reconstruction Amendments by the Supreme Court reentrenched governing systems that abjected Black communities and marked them as disposable.Footnote 25

This legal and social abjection was a continuation of the structures of anti-Blackness in the United States that had underpinned the system of chattel slavery for so long. The result, as Hartman explains, was a “discontinuity between substantial freedom and legal emancipation.”Footnote 26 The written codification of legal rights was simply not enough to undo entrenched discourses that articulated not just the unfreedom of Black Americans, but their status as property—that is, as nonhuman. Within this regime of white supremacy that perpetuated the social structures of chattel slavery after its technical end, Black Americans remained “the object of the law's violence without ever being subject to the law's protection.”Footnote 27 Throughout the Jim Crow era, this led to the increasing criminalization of Black Americans and the conflation of Blackness with lawlessness. What began as the promise of a newfound freedom and equal citizenship for Black Americans quickly turned into “slavery by another name.”Footnote 28

The government's failure to transition Black Americans’ legal legibility within the postbellum system effectively, from being identified primarily as property before the war to being recognized as full citizens after the war, is evidence of the separability of legal texts and lived experience within a legal system, or the distance between the law-as-text and the law-as-performed. Active defiance by white officials and the historical residue of white supremacy that clung to legal, penal, and carceral structures worked in tandem to prevent this transition and to solidify the estrangement of Black Americans from legal protection, regardless of what the law itself said. Yet the law-as-text and living law are not opposites, but rather coproducers of legal, and racialized, subjectivity. Within social systems, de Certeau argues, the “law ‘takes hold of’ bodies in order to make them its text.”Footnote 29 Just as the law-as-text cannot guarantee rights without physical and social reinforcement, the law-as-text doesn't exist without bodies upon which to inscribe its meaning. In language that calls forth the theatrical dimensions of this process, de Certeau asserts that law “transforms them into . . . living tableaux of rules and customs, into actors in the drama organized by a social order.”Footnote 30 While the antebellum social order was upended during Reconstruction, during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the general expressions of that social order had been reasserted, often violently, by white Americans.

This social order was defined by the reinstatement of legal alterity: Black people have always been “held” differently by the law than white people, and the undermining of Reconstruction reasserted antebellum inscriptions of Black people under the law. The echoes of that social order continue to reverberate today. De Certeau explains that the process of inscription requires an “apparatus” to translate the text onto the body. In earlier times, this apparatus may have been a tattoo, or even a brand—calling to mind antebellum practices of branding enslaved people, thus marking them as the “property” of the enslaver.Footnote 31 In both Sweet's time and the present day, however, the “instruments” used to inscribe bodies with the law “range from the policeman's billyclub to handcuffs and the box reserved for the accused in the courtroom”—and the jail cell.Footnote 32 These strategic instruments are the tools for perpetuating white supremacy, enforcing an unequal lived experience of the law for Black people in the United States. While the text of the law is ostensibly neutral, the protective application of that text has, throughout most of US history, been a benefit limited to white men. So, too, have other constitutional rights, including the right to keep and bear arms in self-defense.

Ossian Sweet grew up during the period of retrenchment following Reconstruction, and his experiences reflect the reality of Redemption's success in Florida: his parents, who had managed to purchase a small home lot, worked tirelessly in the fields to make ends meet; he and his siblings attended underfunded Black schools that enrolled students only up to the eighth grade; and, in 1901, five-year-old Ossian witnessed a horrific lynching near his home in Bartow. Throughout his life, including when he took the stand at his own trial, Sweet described hiding in the bushes near his home in Bartow and watching a white mob lynch Fred Rochelle, a Black sixteen-year-old who had been accused of raping and murdering a white woman. The mob caught the young man, tied him up, doused him with kerosene, and set him on fire. Sweet related visceral memories of the sound of Rochelle's screams and the sight of members of the crowd picking off pieces of the dead youth's flesh to take as souvenirs.Footnote 33 Sweet's recollection stood in stark contrast to the local newspaper's editorial page, which argued that the lynching was “done decently and in order by sober and serious men, possessing the full average of kindly instincts” and “the spontaneous work of practically all the best citizenship of this place.”Footnote 34 For Sweet, the memory of Rochelle's violent killing imprinted upon him the sudden, arbitrary, and blindingly violent nature of white mobs.

Rochelle's killing, and these two historical records of it—Sweet's memory and the contemporaneous newspaper accounts—demonstrate how violence is used as a strategy by the powerful and how tactical lawfulness can repurpose that strategy through performance. In the case of lynching, the violent nature of the act, and the fact that it was often perpetrated against Black Americans who had successfully staked a claim to visible public citizenship, was a means to reinforce the power of white supremacy and, in particular, the segregated control of public spaces.Footnote 35 Sweet, on the other hand, would use his own racialized trauma caused by witnessing Rochelle's murder to explain why he defended his home with guns. Performing the role of masculine protector for a jury and eager newspaper readers, Sweet explained in interviews and during his trial that the residual fear of white mobs that was initiated in that moment of childhood witnessing persuaded him to arm his friends and family that night on Garland Street. Sweet's deployment of his own memory of Rochelle's killing was a tactical use of that same violence to legitimize his act of lawful self-defense.

Ever since Sweet had witnessed the lynching of Fred Rochelle, anti-Black violence had been a constant reminder of his own precarity and second-class citizenship. In the South, lynching and other forms of extralegal racial terrorism had proliferated, shading everyday Black life with the threat of imminent violence. Florida was a particularly brutal place to grow up; historian Darryl Paulson points out that “Florida trailed only Mississippi in the number of lynchings per capita” perpetrated from 1890 to 1930.Footnote 36 White violence against Black Americans was hardly limited to the Deep South, however. In the first decade of the twentieth century, white people led devastating pogroms against their Black neighbors not only in Atlanta, Georgia, but also in Springfield, Ohio, and Springfield, Illinois.Footnote 37 Scores of Black Americans were murdered, hundreds were injured, and thousands were driven from their homes.Footnote 38 As more and more Black Americans migrated to the North in search of better economic opportunities, racialized violence increased in northern cities—violence that reached a peak during what James Weldon Johnson termed the “Red Summer” of 1919, while Sweet studied at Howard University.

Sweet's road to Washington, DC, and Howard University was typical of the journeys of many Black Americans who aspired to be part of “the talented tenth.”Footnote 39 When Ossian was thirteen, Henry and Dora determined that he had no future in Florida and sent him to Ohio, where he would complete a four-year preparatory course at Wilberforce University, a Black college owned and operated by the African Methodist Episcopal Church. After completing that course of study, he would matriculate into the university, graduate, and join the upper echelon of Black achievement. While at Wilberforce, Ossian gained not just a secular education, but also instruction in the moral values of the AME Church, business strategies, and the racial politics of radical Republicanism. Remarkably, Ossian also learned first aid, tactical maneuvers, and small arms while at the university, a vestige of the Reconstruction-era decision to institute a military training program there.Footnote 40 By the time he entered medical school at Howard University, Ossian was well on track to exceed the monumental expectations that his parents had set for him—and, unbeknownst to him, to become a symbol of Black resistance to white violence.

Sweet had been industrious and committed to his education, and it was not until he was directly confronted by racial violence in his own neighborhood that he fully developed a commitment to armed self-defense. As Arthur Garfield Hays, one of Sweet's defense lawyers, would later write, Sweet “had seen men hunted through the streets” during the anti-Black violence in Washington, DC, during July 1919. From that experience, Sweet “had learned that the only thing which saved hundreds from extermination was that they were prepared to and did defend themselves.”Footnote 41 Following white racist pogroms in East St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Houston in 1917 that killed hundreds and displaced thousands, the attacks in Washington were the first of a new wave of mass white violence that swept the United States in the summer of 1919. Escalating nationalism, anti-immigration fervor, and racist sentiment toward Black migrants from the South contributed to rising racial tension; the addition of (unproven) accusations of sexual assault against Black men in Washington caused a conflagration. In July, white soldiers laid over in Washington went on the rampage. They attacked Black people on the streets (including in front of the White House) before targeting the Black sections of town.Footnote 42 Though the southwest neighborhoods fell under the onslaught, Black Americans in the northwest areas of the city prepared to meet the mob with force, buying “up any gun that was for sale” and “grabb[ing] free weapons that had been rushed in from Baltimore.”Footnote 43

The white racial violence that had flowered throughout the United States, and now was enacted in the nation's capital, was a means of policing the strategic spaces of whiteness by attempting to destroy Black communities. Black resistance to this strategic violence was a tactical intervention, using the spaces and techniques of the oppressive power—of white Americans—to resist that control. Because it was both legal and theatrical, publicly taking up arms for self-defense during these spasms of white racist violence was an act of tactical lawfulness, one that would influence Sweet's later actions. When white rioters reached the Black neighborhoods of northwest Washington, DC, they were met with gunfire raining down from the houses and Black Americans ready to shoot if attacked on the street.Footnote 44 Gun battles flared; public streets and busy intersections became impassable, even for police.Footnote 45 Finally, the streets were quieted, as President Woodrow Wilson called in two thousand federal troops and a furious rainstorm lashed the capital.Footnote 46

Black leaders saw the white racist violence in Washington as a turning point. They identified neither the rain nor the troops as the reason for the violence's end, but rather the visible spectacle of Black Washingtonians’ willingness to meet force with force. Johnson wrote about arriving in Washington on 22 July and finding the Black residents preternaturally assured in spite of the brutal violence targeting them: “they had reached the determination that they would defend and protect themselves and their homes at the cost of their lives, if necessary, and that determination rendered them calm.”Footnote 47 Later, in meetings with government officials and the editor of The Washington Post, Johnson emphasized that Black Americans were responsible for ending the violence—by taking up arms of their own, and relying on neither protection from the government nor support from the media. “The Negroes saved themselves and saved Washington by their determination not to run, but to fight—fight in defense of their lives and their homes,” he stated. “If the white mob had gone on unchecked—and it was only the determined effort of black men that checked it—Washington would have been another and worse East St. Louis.”Footnote 48 Johnson also warned government officials that their unwillingness to quell racist violence would lead to more, and more brutal, armed engagements elsewhere, as Black Americans would “no longer submit to being beaten without cause,” but would protect themselves with defensive violence if necessary.Footnote 49

Johnson was right about governmental neglect leading to additional anti-Black attacks. The Red Summer of 1919 was a brutal one for Black Americans as they were targeted by white racist pogroms in Chicago, Knoxville, Omaha, and at least twenty other cities.Footnote 50 Though the violence abated in 1920, the shadows of state and vigilante violence still stalked Black Americans, both in the North and the South, and Ossian Sweet was steeped in the fear, anxiety, and resolve with which Black Americans met this threat. Leaders and activists in the cause for Black rights initiated public conversations about whether Black Americans ought to use violence to defend their homes and lives, or whether they ought to strive for “conciliatory methods” and “forbearance” in the face of racist violence.Footnote 51 Some of the most towering figures, including Johnson, DuBois, and Walter White, argued that they had practiced conciliation long enough. “For three centuries we have suffered and cowered,” wrote DuBois in the September 1919 issue of The Crisis. He continued:

No race ever gave Passive Resistance and Submission to Evil longer, more piteous trial. Today we raise the terrible weapon of Self-Defense. When the murderer comes, he shall not longer strike us in the back. When the armed lynchers gather, we too must gather armed. When the mob moves, we propose to meet it with bricks and clubs and guns.Footnote 52

Though there is little indication that Sweet participated directly in the public discussions about Black self-defense roiling in the aftermath of the Red Summer, his later testimony would articulate how the anti-Black violence—and Black Americans’ move toward self-defense as a political position—influenced his state of mind on the night that a white mob descended on his house. By growing up Black in the United States, Ossian Sweet was positioned as an outsider in his own country; that embodied experience gave him both evidence of the strategies of white supremacy at work and the raw material to compose a tactical strike against the state.

In the spring of 1925, three years after they were married, Ossian and Gladys purchased a home on Garland Avenue in Detroit. They had just returned from Vienna and Paris, where Ossian had completed additional medical training with some of the brightest names in science, including Marie Curie, whose seminars at the Sorbonne he attended. It was a program of study far surpassing anything Ossian had access to in the United States. The Garland house was a bungalow constructed in the Arts and Crafts style, tucked neatly on a corner lot in a part of town that was solidly working class—and solidly white (see Fig. 1). Ossian and Gladys knew that they faced grave danger from their new white neighbors, but they were resolved in their decision to take possession of the house. On 9 September 1925, the day after they moved in, the Sweets received a call from a friend who had overheard a white woman on a streetcar that morning talking about them. “Some ‘niggers’ have moved in and we're going to get rid of them,” the woman told the conductor. “They stayed there last night, but they will be put out tonight.”Footnote 53 Ossian and Gladys knew their lives, and the life of their baby daughter, Iva, were at stake.

When the Sweets moved into their home in September, Detroit was in the grip of a resurgence of overtly white supremacist political action.Footnote 54 Though the North experienced a marked drop in the mass racial violence that had characterized 1919, the country as a whole was reeling from additional devastating anti-Black pogroms, including those in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Rosewood, Florida. Black Americans continued to move from the rural South to northern industrial cities, and the segregated areas in which they were permitted to settle became balefully overcrowded. As increasing economic competition inflamed white supremacist attitudes, the Ku Klux Klan reemerged as a powerful political force. Unlike its more covert first iteration, this version of the Klan embraced a public role and claimed upstanding citizens, police, and political leaders among its membership.Footnote 55 Also unlike its first iteration, this Klan quickly spread through northern cities that had large numbers of Black Americans, particularly those that had seen a rapid influx in the previous decade. In the years preceding the Sweet trial, Klan membership ballooned in Detroit, and in 1924 the group fielded a candidate for mayor. Alongside the increasing influence of large-scale groups like the KKK, white Detroiters also began forming local neighborhood improvement organizations, whose banal-sounding names obscured a more insidious purpose: to keep Black Americans from purchasing homes in white neighborhoods.Footnote 56 These groups were another means for strategically enforcing spatial control, and in the Sweet trial it emerged that one such group, the Waterworks Park Improvement Association, had been established for the sole intent of preventing Ossian and Gladys from inhabiting the home they had purchased. Because it focused so clearly on both the right to possess and protect one's home, the Sweet's home defense and later trial presented a public, theatrical arena in which the two sides battled out who was permitted to belong—whose lives could be woven into the civic fabric of the nation.

Upon hearing about the impending attack on their house, the Sweets were faced with a decision: leave the Garland house, and possibly never reclaim it as their home, or defend it—with arms, if necessary. They opted for the latter. Early in the evening on 9 September, a crowd began to gather outside the Sweet home, clumped in small groups on neighbors’ lawns and in the yard of the nearby elementary school. Tipped off about the potential violence, police were patrolling the area, keeping people from congregating directly in front of the house. Ossian had gathered a group of nine men to help him and Gladys with their planned defense, and earlier in the evening he had rehearsed elements of the potential attack with them, picking out the right guns and ammunition for their task and staking out key defensive positions inside the house. As hundreds of people gathered in the street, ready to attack the Black inhabitants inside, Ossian drew on countless real and imagined scenarios of white mob violence. A scenario, as Diana Taylor explains, is a “meaning-making paradigm[ ]” that is “formulaic, portable, [and] repeatable.”Footnote 57 The scenario of white violence against Black Americans is constitutive of the social order in the United States, an event that has been reenacted throughout US history to preserve a white supremacist status quo. Sweet had innumerable past scenarios to draw on in that moment: not just the lynching of Fred Rochelle or the attack on Dr. Turner, but the Red Summer and every legal and extralegal attack Sweet had read about, heard about, or even imagined. When the attack on the Sweet home began in earnest, those inside didn't delay the ending they had envisioned; within moments of a rock breaking a second window, several people inside the house let loose a volley of gunfire into the crowd. Ossian and his companions had imagined a potential attack, they had planned for it, they had rehearsed potential armed responses, and, in the end, they had followed through on their plan to defend the home and family who lived there.

Ossian, Gladys, and the others in the house that night were acting lawfully. Self-defense law is notoriously slippery, conditioned as it is on the “reasonableness” of the response to potential violence, but since the time of colonization and the importation of English common law into what would become the United States, the so-called castle doctrine has governed legal conceptions of self-defense and the home. This legal notion emerged from a case in England in 1604, in which the attorney general argued that forcible entry into a person's home was unacceptable. “The house of every one is to him as his castle and fortress, as well as his defence against injury and violence as for his repose.”Footnote 58 This observation, according to Caroline Light, is the basis for the truism that “a man's house is his castle,” and it has served as the basis for self-defense law in the United States since the seventeenth century.Footnote 59 This history is reflected in Pond v. People, an 1860 decision by the Michigan Supreme Court in which the court held that the law does not require actual danger as a condition of self-defense; it requires only that the defendant had a reasonable belief that he was in danger.Footnote 60 This decision also asserted that “a man assaulted in his dwelling is not obliged to retreat, but may use such means as are absolutely necessary to repel the assailant from his house, or prevent his forcible entry, even to the taking of a life.”Footnote 61 Though the law did not always protect Black Americans, Sweet and his companions that night took the law at its word, performing the act of self-defense in a way that reflected both an instinct for survival and careful planning of a visible, spectacular response to threat. It was this lawfulness and performance of protective masculinity that attracted the NAACP to Sweet's case. The organization's leaders were looking for cases that would highlight the difference between the law-as-text and the law-as-performed. The text of the law was clear—Ossian and the others were legally within their rights to enact armed defense of the home; the real question, however, was whether they would be permitted to perform that right.

Sweet's case came about at a moment in the NAACP's history when its leaders were utilizing theatricality to mobilize support for Black citizenship rights. As part of their campaign to eradicate extralegal anti-Black violence, the NAACP supported the production of Black-authored drama that acted as a counterweight to both the demeaning portrayals of Black people in minstrelsy and the horrific theatrical spectacle of lynching. The plays that form the canon of “lynching drama” depict not the violation of Black bodies, but instead the trauma of Black households impacted by the violence of these two forms of racist entertainment.Footnote 62 These plays, Koritha Mitchell argues, were less a means to resist lynching than to demonstrate the love and stability of the Black family and community; they are, she argues, a “self-affirmation.”Footnote 63 In 1916, the NAACP in Washington, DC, sponsored a production of Rachel by Angelina Weld Grimké. Grimké said that Rachel was created specifically to appeal to white women—to convince them that Black families were just like theirs, and that the trauma and emotional impact of lynching were truly profound.Footnote 64 She was hoping that the embodied experience of watching the family in the play would generate enough empathy to spark white resistance. To this end, the play is a sentimental drama set in a domestic sphere and focused on a young woman, Rachel, who has to cope with the reverberations of her father and brother's lynching several years before the play begins. Lynching plays, as acts of self-affirmation, were tactical interventions that repudiated the strategic control of Black life exercised by other forms of entertainment, particularly the minstrel show and white-authored melodrama, a genre that had found one of its most popular manifestations the year before with the release of the white supremacist film The Birth of a Nation.Footnote 65 Through its support of Grimké's play, its establishment of a drama committee, and its publication of other lynching plays in its magazine The Crisis, the NAACP clearly recognized drama's tactical potential, including the possibility that it might shift white cultural perceptions of Black Americans in the early twentieth century.Footnote 66 Ossian Sweet, and his defense attorney Clarence Darrow, clearly recognized this potential as well, and, during the trial, they capitalized on performance's unique ability to generate empathy across lines of racial difference.

While lynching was the most physically immediate threat to Black Americans in the early twentieth century, it was by no means the only strategic oppression they faced. Alongside lynching, Black Americans also faced widespread disenfranchisement and racial segregation, all of which served the purpose of reestablishing a permanent, white supremacist racial caste system in the aftermath of Reconstruction. The particular linkage between lynching and housing segregation, a connection that would become central to Sweet's defense, was clear to many Black leaders, including those in the NAACP, in the early twentieth century. An editorial from the Philadelphia-based Public Journal made the affiliation explicit: “Lynching has been the peculiar institution of the South,” the writer warned. “Forceful residential segregation has taken root and is spreading so fast till if it is not soon checked it will become the peculiar institution of the North.”Footnote 67 The author then emphasizes the particular strategic performances the two share:

Like lynching in the South[,] those who would enforce the principle of Residential Segregation in the North, are arrant cowards, for their methods are the same. The mobs of a thousand men, women and children, lynch and burn one lone man in the South. In the North, the mobs gather under cover of night and threaten and intimidate and hurl stones upon a man and his family—cowards all!Footnote 68

The affiliation between extralegal white supremacist violence and legal residential segregation, along with the disenfranchisement of Black voters, cohered as an all-out attack on Black Americans’ “God-given right[s] vouchsafed by the Constitution.”Footnote 69 The psychological effects of this unrelenting attack on Black Americans would come to form the basis of Ossian Sweet's staging of tactical lawfulness during his trial—a performance that would ultimately lead to the freeing of all eleven defendants.

Ossian Sweet's defense of his home and the trial that followed was one of the first, and most impactful, examples of Black Americans turning to the courts to protect their right to armed self-defense. Sweet, the leadership of the NAACP, and his defense team identified the courtroom as a strategic space of the state within which they could tactically intervene, using the authoritative space of the trial to interrogate the very foundation of (racialized) justice in the United States. Additionally, Sweet took the opportunity of his trial performance to undermine the theatrical tropes of Black buffoonery, weakness, and shiftlessness that had been circulated by minstrelsy. Instead, he placed the sober, traumatized family of lynching drama on the “stage” of the courtroom and asked the jury, much as Rachel asked its white audience, to imagine themselves in his place. In so doing, he asserted a right to empathy for his performance of armed tactical lawfulness—anyone, Black or white, would have defended his home, family, and right to life in a similar way. Sweet's home defense was a performance of masculine self-making that demanded his inclusion in the social fabric of American life.

A Tactically Lawful Testimony

When he finally took the witness stand in a Detroit courtroom on 18 November 1925, Dr. Ossian Sweet needed to convince the all-white, all-male male jury of two things: (1) that he and his ten codefendants had been acting in self-defense when they fired on a crowd of white protesters across the street from his new home, and (2) that he was a full citizen of the United States, entitled to all the legal rights and protections that such citizenship guaranteed. Sweet's ability to persuade the jury of these claims was in no way assured. In the first instance, the prosecution had, earlier in the trial, argued that Sweet and his codefendants had conspired to murder members of the crowd by firing on them without provocation. Though Darrow, Sweet's lead attorney, had robustly challenged these claims in his cross-examinations of state witnesses, there was no clear indication that the defendants would receive a fair hearing of the evidence. In the second, Sweet had seen over and over that Black Americans’ claims to citizenship and legal enfranchisement were rarely fully practicable even if they were guaranteed on paper. There was no promise that, even if Sweet's attorneys could prove that the shooting was justified, it would be enough for the all-white jury to acquit. As journalist Marcet Haldeman-Julius observed, the central question of trial was not simply whether Sweet and his codefendants acted in self-defense; “no disinterested person could doubt it,” she scoffed. Instead, the outcome of the trial “went to the very roots of the Negro's future in this country. Was or was not a colored man a citizen with a citizen's rights?”Footnote 70 Her observation echoed that put forth in a letter to the editor written by James Weldon Johnson: “Will the law guarantee these colored people the right to defense of their homes,” one of the “fundamental citizenship rights?”Footnote 71 Both Haldeman-Julius and Johnson identified the paradox of textual versus performed rights: if a person is a citizen in law, but not in practice, is he or she a citizen at all?

Sweet began his testimony by describing the attack on his home in vivid detail. The Sweets had moved into the bungalow-style house on the corner of Garland and Charlevoix Avenues in Detroit on 8 September 1925. Their first night there had been an uneasy one, but had ultimately passed with little provocation, other than someone pelting the house with a few stones around midnight. The next day, however, Ossian and his wife, Gladys, heard rumors that white people were planning a full-fledged assault on their home that night.Footnote 72 And so, Sweet testified, he arranged for nine additional men to join him at the house in order to defend his family's right to be there—with force, if necessary. That evening, while Gladys fixed dinner in the kitchen, Ossian played cards with six friends. There was an abrupt thud as something heavy smashed onto the roof of the house, and, when they looked outside, Ossian and the others saw a crowd gathering across the street. “The people; the people!” someone in the house shouted.Footnote 73

Earlier that evening, Sweet had taken his guests through each room and showed them where he had stashed two rifles, one shotgun, seven pistols, and 391 rounds of ammunition.Footnote 74 As more and more white people gathered outside the house, those inside prepared for an onslaught. Someone in the mob began throwing stones at the house. Sweet testified that he then went to an upstairs bedroom to retrieve one of the guns he had stowed there; he loaded it and laid down on the bed. Suddenly, a large rock crashed through the window, raining shards of glass on Sweet. “What happened next?” prompted Arthur Garfield Hays, one of Sweet's defense attorneys. “Pandemonium—I guess that's the best way to describe it—broke loose,” Sweet replied. Ossian's brother Otis and fellow defendant William Davis arrived in a taxi; as they sprung from the car and sprinted to the front door, the crowd shouted, “Here's niggers! Get them; get them!” The white mob surged forward, “like a human sea” according to Sweet, and stones continued to pound the house. After a rock shattered a second window, several shots rang out from upstairs in response. After a moment, another barrage issued from the second-floor windows. “Then,” Sweet said, “it was all over.”Footnote 75

Although Sweet's recitation of the night's events was evocative, he gave a truly revelatory performance of tactical lawfulness later in his testimony. Hays had promised in his opening remarks two days earlier that the defense would “show not only what happened in the house, but . . . attempt a far more difficult task—that of reproducing in the cool atmosphere of a courtroom a state of mind, the state of mind of these defendants, worried, distrustful, tortured, and apparently trapped.”Footnote 76 That is, the defense would theatrically re-create the experience of being in the house as it was under attack, conjuring the affective past in the present of the courtroom.Footnote 77 This theatrical conjuring was necessary in order to convince the jury not only that the people in the house that evening feared for their lives, but that such a fear was reasonable. It required Ossian's body to perform the text of his testimony in order to generate the affective experience for the jury members, who were Ossian's most important audience. His embodiment is what produced the meaning of the law—the reasonableness of his reaction to the assault on his home.

The courtroom is a strategic space of the state; it controls and perpetuates the state's legal ideologies. One of those ideologies is the belief that citizens have the right to defend themselves and their homes from imminent harm. In the United States, however, the long history of relegating Black Americans to noncitizen status ensures that Black people making a claim of self-defense in the courtroom are presumed innocent far less often than white people are. Sweet needed to convince the jury of his innocence by laying claim both to citizenship and to fear—both the right to use self-defense and the imminent need to do so. To call into being the defendants’ emotional experience of the attack, the defense made a novel claim: that Sweet and his codefendants’ “race psychology” was the key to understanding their overwhelming fear.Footnote 78 When Hays prompted Sweet to delve into his frame of mind on the night of the shooting, Sweet testified that the whole of Black experience in the United States weighed on him as he surveyed the crowd in front of his home:

When I opened the door and saw the mob I realized I was facing the same mob that had hounded my people throughout its entire history. In my mind I was pretty confident of what I was up against, with my back against the wall. I was filled with a peculiar fear—the kind no one could feel unless they had known the history of our race.Footnote 79

Sweet's testimony called forth the metonymic power of theatricality in order to defend his actions; as the specific crowd of white attackers came to stand in for all racist white mobs, Ossian came to stand in for all Black Americans threatened by racial violence. This claim to metonymy was a tactical strike; by acknowledging that Black Americans have a greater reason to fear a mob gathering outside their home than do white Americans, Sweet was using the strategy of the courtroom testimony to advocate for Black citizenship rights, a performance made necessary by the fact that Ossian's jury was entirely white and thus entirely exempt from the kind of fear he was describing.

The effect of Sweet's claim—that an embodied, experiential knowledge of the history of racialized terror in the United States could justify a deadly act of self-defense—was electric. As a legal scheme it was a gamble; the success of the claim relied on Sweet's ability to so persuasively perform his own fear that he would convince jury members that they, as white men, didn't and could never understand the constant, daily fear that Black Americans endured—and that, if they could understand it, they would have reacted in the same way. Sweet was using the state-sanctioned strategic space of the courtroom to perform tactical resistance and reveal the racialized nature of a law that would undoubtedly protect a white man who had used a gun to defend his home and family against a violent mob. The prosecutor, recognizing the potential power of this testimony, immediately objected to its admittance into evidence: “Is everything this man saw as a child justification for a crime 25 years later?” he cried. Hays likewise realized the effectiveness of Sweet's performance. “Yes,” he replied, “I might properly bring in the incidents his grandfather had told to him.”Footnote 80 Walter White, at that time the Assistant Secretary of the NAACP, was in the courtroom for Sweet's testimony, and his exhilaration and relief are evident in a telegram he sent to James Weldon Johnson applauding Sweet's performance: “Trial reached its climax when Dr. Sweet took the stand STOP he made a magnificent witness . . . this line of reasoning demonstrated the psychological background of the Negro which actuates self-defense when attacked by [a] mob.”Footnote 81 An NAACP press release, published eight days later, touted Sweet's triumph in the court, suggesting that his testimony had caused “public opinion [to swing] from bitter hostility to sympathy for the defendants” and assured its readers “that there was good hope of a favorable outcome for the trial.”Footnote 82

The NAACP's good hope for acquittal of all eleven defendants was staked on Sweet's sober performance on the stand. White told Johnson in a separate telegram that Sweet had “helped [the] case tremendously” by conveying his “story with restraint and simplicity that held [the] courtroom breathless.”Footnote 83 White's description draws on tropes of effective acting; the courtroom was Sweet's audience, and he had held them rapt with a masterfully understated retelling of the violence and threat that permeated everyday Black life. In a moderate yet convincing manner, Sweet had relayed his experiences with anti-Black violence. He began with his childhood in rural Bartow, Florida, where he witnessed the lynching of sixteen-year-old Fred Rochelle. He spoke of the fear that prompted him to flee the South as a teenager, and the racial violence he saw firsthand as a young medical student at Howard University in Washington, DC, during the “Red Summer” of 1919. He told as well of those Black families he knew of who had tried to move into segregated neighborhoods in Detroit before him, only to be forced out by threats and violence from their white neighbors. Sweet's testimony made it clear that by the time he had collected an arsenal of firearms and stashed them in his new home on Garland Avenue, his “race psychology”—the embodied experience of being a Black man in America—had prepared him to have both a reasonable fear of white mobs and the determination to fight back when those mobs came to his doorstep.

Sweet's performance on the witness stand was an act of tactical lawfulness, as he used his legal testimony to claim something beyond even citizenship—what Hays described as the “sacred ancient right . . . of protection of home and life.”Footnote 84 By demanding ownership of this right, Sweet was performing his and other Black Americans’ position as full participants in legal, civic, and social life of the United States. A claim to masculinity and the centrality of ownership to personhood is implicit in Sweet's testimony, and Sweet was a compelling witness at least in part because his presentation of himself was as an upstanding man who had fashioned himself into an ideal of accomplishment, in spite of the hurdles he had to overcome: he had focused on education, worked hard as a young man, found success in a respectful profession, purchased a home, and was protecting his wife and daughter. As Koritha Mitchell has argued, Sweet's very success is that which made him a target of white violence, since “traditionally defined Black domestic success draws the country's most vicious assaults.”Footnote 85 His self-fashioning on the stand as a masculine protector, however, drew on that same domestic success and offered a space for connecting with the jury. This is yet another example of Sweet repurposing the strategies of the powerful into the tactics of the oppressed. After the Civil War, “arguments on behalf of Reconstruction measures . . . attached great weight to the fashioning of ‘true manhood’ in realizing freedom and equality.”Footnote 86 Sweet was laying claim to this manliness through a scenario that has long been a paragon of white masculinity—the armed defense of one's home and family. Rather than ceding the courtroom to the state's strategic power, Sweet claimed the space as his own, making it the stage for his performance of the racialized experience of being a Black American man. Against the backdrop of popular depictions in film and theatre of Black masculinity as threatening, silly, or lazy, Ossian's testimony proved that he, instead, was protective, sober, and resourceful.

A trial, as many scholars of performance and law have noted, is a theatrical event in which two sides attempt to put their own narrative interpretation onto a set of agreed-upon facts in order to persuade an audience—either a jury or a judge—to agree with them.Footnote 87 It is a strategic space of the state, but one rife with possibility for tactical intervention. Within a trial, dramatic conflict is manufactured, and, though honesty is ostensibly valued, the whole, unvarnished, and tedious truth can, and often does, lose out to a better story told more effectively. As Janet Malcolm suggests, the question of narrative is always at the heart of a trial, and in two competing ways: (1) the narratives that opposing sides tell the jury, and (2) the struggle of narrative in general to overcome the “constraints of the rules of evidence, which seek to arrest its flow and blunt its force.” Rather than the story that is more “true,” it is “the story that can best withstand the attrition of the rules of evidence . . . that wins.”Footnote 88 In Ossian Sweet's trial, he had an excellent storyteller who knew how to expertly weave together the narrative of a haunting race psychology with the theatrical ritual of uncovering legal truth: Clarence Darrow, the “Great Defender,” who had been retained by the NAACP to defend Sweet and the other ten defendants.

Darrow's role in the defense was both as shaper of the narrative and as intercessor for the jury. During the trial, Darrow methodically chipped away at the prosecution's story that there had been very few people outside the Sweets’ home that evening, that there was no mob, and that the eleven people inside the house had conspired to carry out an unprovoked murder by shooting into a peaceful group of white neighbors. Darrow, utilizing the elements of dramatic storytelling to his benefit, established that, in fact, there had been a large crowd gathered, members of that crowd pelted the house with stones, attacked Black people in the vicinity of the house, and, eventually, were dispersed by police following defensive gunfire from the house. It was such an effective argument that David Lilienthal, a journalist for The Nation, exclaimed that “few criminal cases have combined the dramatic intensity, the forensic brilliance, and the deep social significance present in the trial . . . of Dr. Ossian Sweet and ten other Negroes charged with the murder of a white man.”Footnote 89 As Lilienthal's observation makes clear, a central element of the defense's success was Darrow's star power; as an authoritative white man, Darrow gave his imprimatur to the defense's story. Sweet had to contend not only with enacting his defense and his race psychology for the jury, but also with how his Blackness would be read and interpreted by that jury, how his flesh exceeded the discursive performance of his testimony.Footnote 90 Darrow stood in as his surrogate, giving the jury the opportunity to trust him, even if they didn't trust Sweet—and the opportunity to be magnanimous. While it is undeniable that Sweet's testimony was powerful and some members of the jury must have been able to imagine themselves into his place, Darrow didn't make acquittal contingent on that affiliation. Instead, he appealed to jury members’ sense of justice on behalf of the white race. Lilienthal described the lawyer's move succinctly: Darrow, he wrote, “seemed to be pleading more that the white man might be just than that the black be free, more for the spirit of the master than the body of the slave.”Footnote 91 After giving the jury the chance to identify with Sweet, Darrow reassured them that they didn't really have to in order to acquit the defendants.

The Sweet case, in taking up both a fight against segregation and a fight for the right of self-defense, got straight to the center of the question of belonging and citizenship. Not just private citizenship—anyone could keep a gun in his home if no one found out about it, and people, even Black Americans, were allowed to live in segregated (if patently unequal) neighborhoods—but public citizenship: the right to live in any neighborhood unmolested, to own a gun, and to use it in one's own defense. On trial was the right to publicly demand admittance into the civic sphere, to openly engage in the rights of citizenship guaranteed by the Constitution, and to perform social belonging. The Sweet trial, by positioning Ossian as the stand-in for Black America, was a refutation of the processes of civic abjection that had isolated and oppressed these communities. It was itself an act of tactical lawfulness. Through his masterful performance detailing how his race psychology pushed him to act, Sweet laid claim to the text of the law—he took it at its word. Sweet's tactical performance at trial revealed the constructed, racialized nature of the law's application and underlined the ability for jury members and the judge to change that application by seeing, hearing, and treating a Black man as a full citizen of the United States who is entitled to the rights and privileges that citizenship bestows. Sweet opened a space for Black Americans to utilize the law in their behalf. The gambit neither wholly succeeded nor wholly failed: the trial ended in late fall with a mistrial, the result of an impossibly hung jury.Footnote 92

Though Sweet's supporters were initially dismayed by the outcome of the trial, eventually they viewed it as a relative victory. The needle had moved, ever so slightly: at least the defendants weren't convicted outright. Ossian and Gladys were celebrated for ritually and metonymically representing “the whole Black American citizenry,” and to raise money for what was sure to be many additional trials, they began touring, giving accounts of the attack, their home defense, and the trial at mass meetings organized by the NAACP.Footnote 93 Ossian in particular was an enormous hit as he recounted his performances of gun ownership and metonymic representation of Black Americans for audiences who “leaned forward with eager eyes and ears to see this world-famous defendant and to hear his forceful touching story.”Footnote 94 Newspaper accounts of the Sweets’ appearances reaffirmed the idea that the defendants had taken “on their shoulders the fight of an entire segregated group” and voiced “the protest that thousands of their fellows had been silently feeling.”Footnote 95 Ossian and Gladys's performances of belonging resonated with the Black Americans who withstood bitter winter weather to hear their account in person: the NAACP was able to raise over $76,000—money that would provide the foundation of their storied Legal Defense Fund. Thus, Ossian and Gladys's posttrial public recitations of their acts of tactical lawfulness, performed in front of Black audiences across the country, provided financial support for future Black performances of tactical lawfulness, such as legal challenges to segregation, including Brown v. Board of Education in 1954,Footnote 96 and offered a model for later performances of self- and community defense, such as those enacted by the Black Panther Party in Oakland in the late 1960s.

A retrial was scheduled for the spring, but prosecutors declined to retry all the defendants, focusing instead on Ossian's little brother, Henry, who was the only one in the house who confessed to having fired a shot. Darrow and Hays replicated their defense from the fall trial, and this time to much greater success: Henry was acquitted in June 1926. After Henry's acquittal, the prosecutor dropped all charges against the other defendants. The Sweets’ legal drama was over. Even after the trial and his appearances on behalf of the NAACP, Ossian Sweet's performances of armed tactical lawfulness continued. When his and Gladys's daughter, Iva, died of tuberculosis later that year, they went to bury her in the local cemetery. The groundskeeper demanded that they enter with her tiny casket through a rear gate—the one designated for Black funerals. Ossian refused, revealed the gun he was carrying, and demanded that the attendant open the gate. The Sweet family entered through the front to bury their daughter.Footnote 97

The success of the Sweet trial elides the real shortcomings of tactical lawfulness. For de Certeau, the oppressive power always has strategies and the oppressed are always relegated to tactics, which are, by nature, primarily responsive, less impactful, and harder to maintain than strategic instruments. Tactics often represent short-lived victories and rarely result in the overturn of power structures. Individual victories in the courts don't necessarily translate into systemic change, particularly in a country in which the residue of chattel slavery ensures that legality still is not the determining metric of safety for Black Americans and that Blackness is often identified by white people as lawless and inherently threatening. Law enforcement officers and suspicious (white) neighbors police public and residential spaces and map criminality upon Black people who enter those places—resulting in real physical and psychological harm to Black people who are simply living.Footnote 98

Ossian Sweet's legal defense, though individually successful, did not make the legality of self-defense practically applicable for all Black Americans. Despite tactical successes throughout history, powerful strategies of anti-Blackness continue to shape life in the United States, as evidenced by the fact that the castle doctrine and legal measures of “reasonableness” more often than not work against Black victims and defendants, excusing white violence and police brutality by asking juries to imagine what their response would be if they encountered a Black person who made them fearful. That anti-Blackness remains sticky; it is what Christina Sharpe identifies as the “total climate” of everyday life.Footnote 99 Richard Rothstein, writing about the continuing impact of redlining and racially restrictive covenants, argues that the result of these policies has been to create a permanent racial caste system that continues not just to disadvantage Black Americans, but to ensure their lack of access to legal redress, health care, education, and social mobility.Footnote 100 In short, the strategies of white supremacy remain intact today, and acts of tactical lawfulness can appear to mount only fleeting challenges to that power. I wish to contend, however, that there is potential in the practice of using the law against itself to enact racial redress. Even if he and Gladys never again lived in the house on Garland Avenue, Ossian Sweet's acts of tactical lawfulness—his armed defense of his home, his trial testimony that highlighted his racialized experience, and his sharing of that narrative in the public sphere—were revolutionary, seeding material resources and liberatory tactics that would flourish in the coming decades, enabling ever more substantial legal and social challenges to white supremacy.

Lindsay Livingston is Assistant Professor in the Department of Theater and Dance at Bowdoin College. Her work investigates the intersections among performance, race, violence, and public space. Her current book project, Extra Ordinary Violence: Performance, Race, and the Making of U.S. Gun Culture, argues that gun culture in the United States is reflective of and conditioned by racialized performances of citizenship and public inclusion, both onstage and in everyday life.