Similar to many formerly colonised societies, the Philippines’ late modern history has been clouded by narratives highlighting the roles of western regimes. Consequentially, colonial agents have eclipsed the part played by local figures in those stories, leading to a frequently skewed understanding of the dynamics that impacted Filipino societies through the 20th century. This paper examines an event-laden period in Philippine history—the late 19th and early 20th century—by tracing political and social patterns set, not only by the colonial regimes that hitherto seem to have defined that era, but by a local society that wielded an unrecognized amount of influence in shaping the nature of colonialism in the southern Philippines. While the year 1898, when the Philippines passed from Spanish to American rule, was a significant year from the colonial point of view, the death of Sultan Jamalul Alam of Sulu in 1881 resulted in a local reorganization of political configurations, rivalries, and conflict that defined the Sulu archipelago in the final decades of Spanish rule and in the first half-decade of American rule. This paper first argues that in late 19th century Sulu, the United States (US) merely stepped into a role occupied in previous decades by Spain within a continuing, locally-defined pattern of events. Secondly, locality-driven rivalries for prestige and control over dwindling regional trade were the engines that drove the shifting configurations of power and frequent violence of that era, not just reactions to the nascent, and still limited American regime nor the Spanish one they replaced, as existing historiography often suggests. Indeed, it was the death of Alam in 1881 that cast a shadow over the archipelago in the long period of transition between centuries, and while colonial activity was certainly impactful, Alam's demise played an underestimated role in Sulu history of this period.

Philippine histories of the late 19th and early 20th centuries are often characterized by a periodization of storylines roughly around the year 1898—when Spanish colonial rule ended and American rule began. This was ostensibly when the overarching theme of Philippine (colonial) history made the shift from the evangelical imperative of Spain (Rafael Reference Rafael1988) to the nationalist and capitalist ethos of the US (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2013). This transition was an outcome of the Philippine revolution of 1896 combined with the Spanish-American war over Cuba in 1898—significant dates in the formulation of the America-inspired, 20th century nation state. Historians writing about the Philippines have often ended their chapters at the exit of Spain, and started new ones upon the entry of the US. This is quite understandable as the former's departure and the latter's first arrival loom large over Filipinos, as both these influences extended throughout the 20th and into the 21st centuries. Even historical texts as recent as those written by Luis Francia in 2010 echo this convention, as the third chapter of his book History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos, is separated from the fourth chapter by the year 1898 (Francia Reference Francia2013). Similarly, Samuel K. Tan, writing in 2008, uses 1898 to divide his fifth and sixth chapters (Tan Reference Tan2008: 50), while Renato and Leticia Constantino, whose emphasis in A History of the Philippines is on the struggle of the Philippines against its oppressors, end their eleventh chapter with revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo's surrender to the Americans in 1898 (Constantino and Constantino Reference Constantino and Constantino1975: 197).

The few historians of Sulu and Mindanao have also followed this convention in framing their narratives, likewise reinforcing this epoch-making around the transition between colonial regimes, occurring when Americans made their way to the distant archipelago by 1899. As colonial accounts and reports remain the primary source of information of this period on Sulu and its people, the Tausug, it is difficult to avoid allowing Spanish narratives to frame the time before 1898, and American ones to frame the years thereafter. Key historiographical sources also help magnify 1898 in significance. An often referenced 19th century writer Montero y Vidal wrote about the later years of Spanish rule in the southern Philippines in his Historia de la Pirateria, but concluded the historical record before the arrival of the US. The US colonial administrator and historian Najeeb Saleeby represents the first effort in English to consolidate a history of Sulu, but in publishing his work in 1908, Saleeby's story of the archipelago essentially ended upon the establishment of American rule there, again reinforcing a turning point set in the period around 1898 (Saleeby Reference Saleeby1963). Later historians have also allowed the colonial change of powers to overshadow pivotal local incidents by giving central prominence to the year 1898 in colonial and nationalist history (and 1899 as well in case of Sulu). Samuel K. Tan, perhaps the most prolific living historian of Sulu, begins his narrative on the Filipino Muslim Armed Struggle in 1900 (Tan Reference Tan1977). Another of Tan's works, A History of the Philippines, ends the chapter on ‘Colonialism and Traditions’ in 1898, followed by the chapter ‘Imperialism and Filipinism’ beginning in the same year (Tan Reference Tan2008). Perhaps the finest history on Filipino Muslims, Muslims in the Philippines by Cesar Majul, follows the precedent set by Montero y Vidal and Saleeby, and ends its story at the close of the Spanish regime. Its locally centred storylines end abruptly and tantalizingly at the arrival of the Americans at the turn of the 20th century (Majul Reference Majul1999).While the coming of the Americans to the Philippines, and their subsequent presence in the Sulu archipelago in 1899 certainly were important in the reconfiguring of power within that emerging ‘capitalist’ colonial state, the reverberations in the Tausug world after the death of Sultan Jamalul Alam in 1881 made an arguably equal, if not greater impact, on the locals themselves. The year 1881 is significant because the political configurations amongst the Tausug after the death of Alam framed their actions (and reactions) at the end of the Spanish regime and the beginning of the American rule. Alam was arguably weakened after his 1876 defeat by the Spanish that drove him and his court from the ancient Tausug capital of Jolo. His death, which removed the weight of the prestige of a warrior prince from the formula, triggered competition amongst his former followers. It was the backdrop against which the colonial transition of the late 19th and early 20th centuries played out, and defined the character of the American order that was established in the decades that followed. While centring the narrative on 1881 admittedly does merely re-periodise this history around another date, perhaps the consideration of a more locally centred turning point can bring to light alternative narratives of significance, particularly those from non-colonial points of view. This exercise may allow us to make a more complete accounting of colonialism and its actual impacts.

Colonial histories often suffer from an over-reliance on accounts by the colonisers themselves. As such, much of what we know about 19th century Sulu is through reports and letters translated by colonial officials. More recently, however, Samuel K. Tan has taken many of these colonial letters written by the Tausug sultans (Tan Reference Tan2005a) and nobility (Tan Reference Tan2005b) and translated them afresh directly from the jawi script of the original letters. Regardless of their colonial provenance, however, these letters are still relatively under-utilized, and can still serve as sources to anchor a locally-centred analysis of the late 19th and early 20th centuries on their own. Nonetheless, additional context can also be provided by recently published compilations of oral poetry by Gerard Rixhon (Rixhon Reference Rixhon2010), and the availability of digitized recordings and transcriptions of historical epics through online collections such as Philippine Oral Epics Footnote 1. This reframing of the decades after 1881 relies therefore on a refreshed understanding of Tausug correspondence with colonial officials.

Conflict under the American Regime

The tumultuous period at the beginning of the American regime in Sulu is frequently considered through the lens of colonial history, defined almost exclusively by colonial actions and designs and influenced only superficially by the Tausug and their reactions. Gerard Rixhon encapsulates the essence of what is often at the centre of analyses of occurrences in Sulu in the early 1900s:

Following the Spanish-American War in 1898, the Americans acquired the Philippines from Spain and eventually forcefully annexed all of Mindanao and Sulu into one country with its central government in Manila. The Tausug fought bitterly against the Americans, but were eventually defeated. (Rixhon Reference Rixhon2010: 6)

Some have indeed looked beyond the transition of regimes and to longer, more extended patterns, linking numerous conflicts of the Tausug past to an overarching theme of resistance. In essence, this is a manifestation of nationalist notions of self-determination—modern concepts of nationhood that are a product of, rather than a precursor to American rule (Tan Reference Tan1973; Hedjazi and Hedjazi Reference Hedjazi and Hedjazi2002). Others have suggested that it was not necessarily imposed rule of colonial powers that inspired revolt, but short-sighted ‘tutelary’ policies that sought to change the Tausug and make them more western or ‘modern’. These interpretations can often juxtapose the local with the foreign, with Tausug actions indicating ambivalence toward impositions from the outside. Peter Gowing emphasized how action by the Tausug and other Moros (Muslim Filipinos) of this era was triggered by Spain's interference in dynastic conflicts and alien policies introduced later by the US, such as taxation and the curbing of slavery (Gowing Reference Gowing1968: 384). Michael Salman focuses on the issue of slavery and argues that it was so central to the economic power of the datu, or local chieftains, that its suppression by the American regime became intolerable, thus resulting in violent resistance (Salman Reference Salman2001). These are indeed valuable analyses, and provide an understanding of how such factors may have played a role in driving history in Sulu at the turn of the 20th century. However, each narrative underestimates how much of an impact internally driven contestations had on not only the Tausug but colonial actions as well.

Other authors have examined Muslim Filipino (known as the Moro) reactions to American colonial rule in ways that demonstrate more local agency, complicating the local versus colonial narrative. Patricio Abinales has described how politically astute datu re-fashioned themselves in the new American order as mediators between the limited colonial state and the isolated, peripheral Muslim societies, clashing with those leaders who were slower to accept change (Abinales Reference Abinales2004[2000]). Michael Hawkins explains how the American regime sought to impose upon and redefine Moros in a way that fit their own understanding of a linear, progressive history. This focused on the Americans’ advanced position on the continuum of progress and time ensuring the benevolence of their tutelary, imperial mission. Some Moros would embrace this imposed identity making, while others resisted it (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2013). Hawkins and Abinales have accounted for internal divisions amongst Moro societies and the complexities of the colonial relationship, but the impetus is still on the reaction to the outside, as opposed to how the outside reacted to forces developing from within. What many of these authors overlook is the extent to which internal political changes in Moro society, like those started in 1881, shaped events in Sulu over the next three decades.

Thomas McKenna is one of the few who place more emphasis on the role played by local dynamics and argues that much of the tumult of the early 20th century came from a desire for hegemony by local datu over their own subjects, which goes further in explaining the concurrent collaboration with, as well as resistance to, colonial rule (McKenna Reference McKenna2000). While his approach provides valuable inspiration for this study, the scope of his work focuses on participants in the Moro conflicts of the 1960s and 1970s. In paying closer attention to obscure colonial reports and local accounts of rivalries between localities in Sulu and their associated clans, we discover newly significant patterns of internal contestation spanning 30 years, many of which take root in 1881.

Tiange, Maimbung, Patikul, Parang, and Luuk

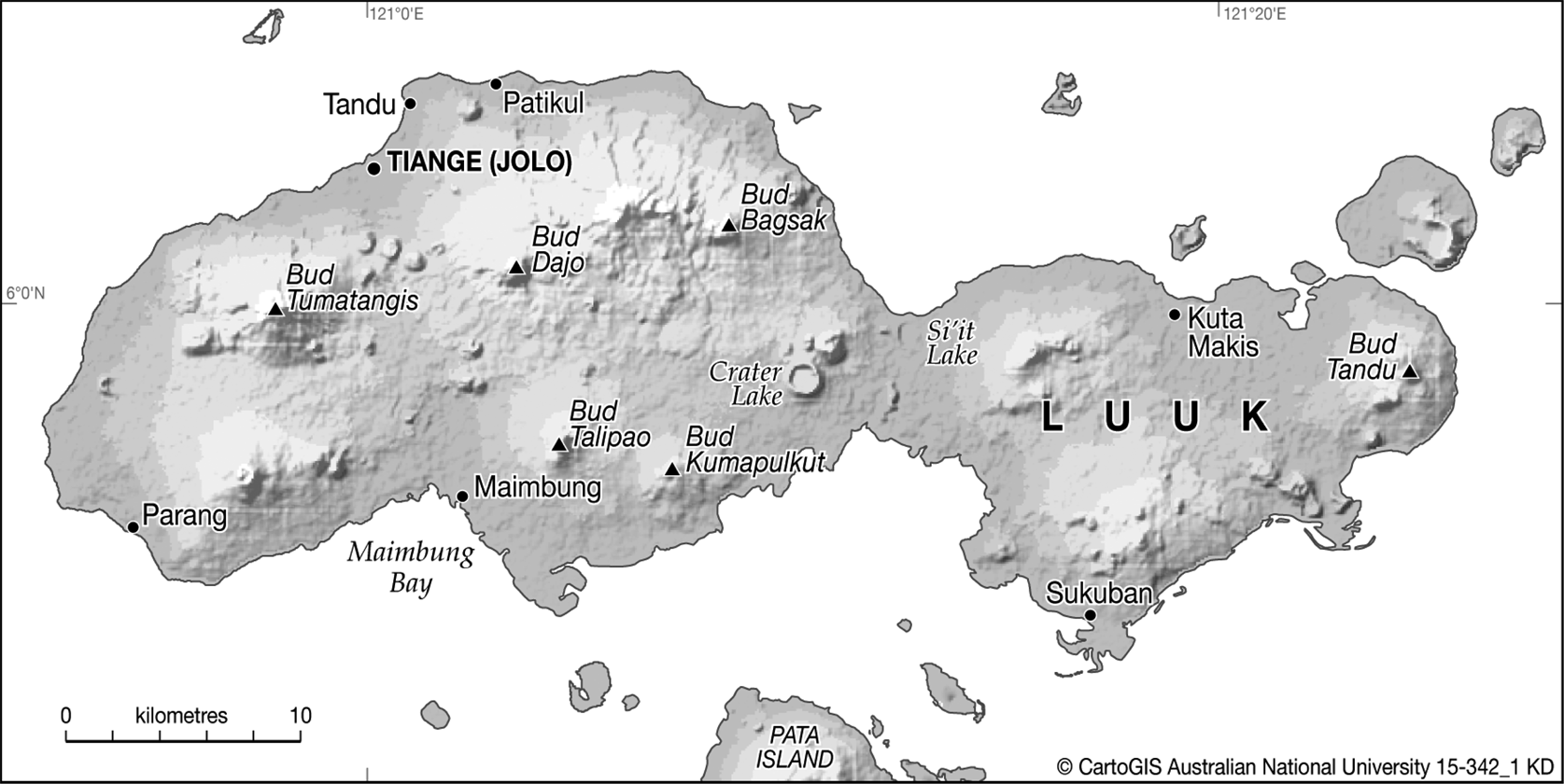

Toward the end of the 19th century, there emerged five loci of power on the main island of Jolo in Sulu. These came to be loosely associated with the townships of Tiange, Maimbung, Patikul, Parang, and Luuk, and these were to drive much of the history of that area for a generation. Comprising the largest island of the archipelago at its central crossing point between the Celebes sea to the south and the Sulu sea to the north, with an area of approximately 870 square kilometres, Jolo island hosted the sultanate's most powerful clans led by chieftains collectively known as the kadatuan. In 1876, the Spanish Admiral Malcampo conquered the town of Jolo, known to the Tausug as Tiange, displacing the sultanate of Jamalul Alam (Montero y Vidal Reference Montero y Vidal1888: 519). Spain had never previously established a permanent foothold in Sulu. After 1876, colonial power never left the archipelago until Philippine independence from the US in 1946. Tiange remained the Spanish colonial base until their departure in 1899, becoming in turn the seat of the American regime.

Maimbung, on the south-central coast, became the seat of the reigning sultanate after its displacement by Malcampo. At approximately fifteen kilometres to the south, Maimbung was relatively distant from the now Spanish-controlled Tiange, but still close enough for Alam to be able to continue encouraging attacks on colonial troops. He mounted an attempt to remove Malcampo's troops from the former capital in February 1877 with 2000 men, was pushed back, and tried again in September of that year. While his power and wealth were bleeding out due to these successive defeats, Alam tried to reinvigorate his campaign with the lease of his possessions in Borneo to the British North Borneo Company for 5000 Mexican dollars per year in January 1878 (Saleeby Reference Saleeby1963: 122). The new and more conciliatory Spanish governor of Sulu, Col. Carlos Martinez, however, made peace overtures to Alam, who received encouragement from his own datus to be receptive. The Treaty of July 1878 saw Alam relinquish control over foreign relations to the Spanish government in Manila, although the sultan maintained the right to unrestricted trade in areas outside colonial control (Majul Reference Majul1999: 354). Alam settled in Maimbung on the southern coast of Jolo island, collecting duties from the hemp, pearl and pearl shell trade there and from the island of Siasi, which received ships on the way to and from Borneo. This was to be the base of the sultanate in the decades to follow. Even as the Spanish government gained more power, Sultan Alam and his retainers continued to enjoy the reverence of Tausug from all over Sulu, and when Alam died, on 8 April 1881, the sultanate was left weaker than it had been for a 100 years.

When Spain ousted Alam's court from Tiange in 1876, one of his most powerful chiefs, the datu Asibi, fled to Patikul, a town just a few kilometres east of the former capital (Saleeby Reference Saleeby1963: 121). A high noble and Alam's relative, Asibi had two sons: Kalbi and Julkarnain, who inherited his power after his death. Their royal lineage and link to Alam meant that Patikul would influence events for the next 20 years in ways that were not always favourable to the sultanate. As we shall see in more detail below, in 1884 the Patikul brothers Kalbi and Julkarnain threw their support behind an outside candidate named Aliuddin, when the succession came under question upon the death of Alam's successor, Badarrudin (Noyes Reference Noyes1900: 21).

A fourth power in Jolo was Parang, a market town, and according to Saleeby, offered the best emporium for pearls, pearl shells, and varieties of fish (Saleeby Reference Saleeby1963:13). Its rapid growth in the mid-19th century, however, was due to the slave trade, primarily with Borneo, as later observers noted the ubiquity of stocks used to imprison people for sale overseas (Official Interpreter 1904e). By the end of the century this trade had declined significantly due to greater European control of nearby waterways. Parang came to play a major role in the disarray triggered by the successive deaths of Alam in 1881 and Badarrudin in 1884. Panglima Dammang, a prominent datu of Parang who defiantly led livestock raids against his rivals during US rule 20 years later, supported an aspirant named Harun al-Rashid to the sultanate. Harun, who gained the backing of Spanish Manila in return for his assistance in negotiating the treaty of 1878, first landed his forces in friendly Parang in his own bid for the throne in 1884 (Montero y Vidal Reference Montero y Vidal1888: 697).

A fifth and newer force emerged in the populous and agriculturally rich eastern region of Luuk. Its leaders were not of royal lineage, but relied on charisma and the emerging popularity of mystics to create trouble for successive sultans and thwart the ambitions of datu in Patikul and Parang. The late 19th century saw this ‘plebeian’ power emerge in an area comprising the immediate eastern side of Lake Siit which lies between the eastern part of the Jolo Island and the west. At the turn of the 20th century, it hosted the largest population in the Sulu archipelago, and was home to the most extensive tracts of cultivated land (Livingston Reference Livingston1915: 37). Luuk was seen by the Tausug as being the “…soul of Jolo [Island]” (Official Interpreter 1904b). In oral traditions on Jolo's conversion to Islam, seven brothers from Luuk were the only men of the island who refused the circumcision rites Islamic missionary Tuwan Alawi Balpaki initiated, delaying their Islamization (Rixhon Reference Rixhon2010: 113). This contrarian reputation persisted into the 19th century. Luuk was notorious amongst the Spaniards for being the source of the dreaded suicide attackers sabilallah, whom they referred to as juramentados. By the late 1870s, Sultan Jamalul Alam was sending his own warriors into the district to control the increasing numbers of sabilallah complicating his diplomatic efforts with Spain (Montero y Vidal Reference Montero y Vidal1888: 589-590). In April 1881, the Luuk chief Maharaja Abdulla led a rogue attack on the Spanish garrison at Tiange a few days after Alam's death. While they were subsequently punished by the new Sultan Badarrudin (Majul Reference Majul1999: 357), these exchanges did much to precipitate the crisis that emerged a few years later. In the American era, recalcitrant chiefs Hassan and Usap, who gave the new regime the most grief during their early tenure over Sulu, emerged from Luuk.

Sulu's five loci of power were also facing economic pressure in the latter half of the 19th century. The datu had thrived on maritime trade (Reid Reference Reid1988) and raiding (Warren Reference Warren2007) in the two centuries before 1881. However, as colonial regimes gained control of waterways and carried out more active patrolling, datus’ mobility reduced and they had little to no access to coastlines outside their home territories, which meant their main sources of income were largely blocked. This heightened the internal competition in Sulu. While reports of maritime raiding predominated during the Spanish era of the early to mid-19th century, in the latter part of the 19th and for most of the American period in the 20th century, it was cattle raiding that was more prevalent. In this sense, the constriction of maritime mobility of the Tausug caused them to turn inward, to raid each other for cattle, rather than across the waterways for slaves.

Despite the shifting economic conditions, Tiange, Maimbung, Patikul, Parang, Luuk and the datu that led them remained the main centres of power in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In paying closer attention to how these centres competed for power on Jolo island, it seems that Alam's ruling line was reinforcing the practice of dynastic succession, reflecting notions of monarchy in the Islamic world present in Sulu due to cosmopolitan influences permeating Muslim southeast Asia at the time. Local datu, meanwhile, purported an older Austronesian premium on prowess—what Abinales referred to as the orang besar or ‘big man’ notion (Abinales Reference Abinales2004[2000]: 49). While it could be argued that Alam's defeat in 1876 is a key turning point in the history of Sulu, his continued presence on the throne was enough to preserve the configurations of power that predated the defeat. The successive ascension of two untried, juvenile rulers after the death of the well-respected, wartime leader Sultan Jamalul Alam in 1881 precipitated this clash between dynasty and prowess, ruling family and kadatuan. While the turbulence around succession eventually settled in 1894 with the ascension of Jamalul Kiram II, animosities continued between these groups, with provocations and posturing in the form of cattle raids, ambuscades, intrigue, and open warfare. This was the background against which the US displaced Spain as colonial ruler in 1899 (Saaleeby Reference Saleeby1963: 137).

Death of Alam and Crisis in 1881

Sultan Jamalul Alam was a popular grandson of the beloved Jamalul Kiram I who ruled between 1823 and 1842 (Majul Reference Majul1999: 21). This dynastic connection kept his own prestige secure, despite successive defeats at the hands of European powers culminating in the loss of Tiange to Spain in 1876. As he lived out the last months of his life in 1881, the kadatuan's support converged around two members of his family. The designated Raja Muda, or heir, was the nineteen-year-old Badarrudin, the son of Alam's first wife. Alam had repudiated his first wife in favour of the younger and intelligent Inchy Jamila who intended to elevate her own son, the eleven-year-old Amirul Kiram, to the position of Sultan. Six days after Alam's death, on April 14 1881, Jamila sent letters to the Spanish Governor Rafael Gonzalez de Rivera trying to declare her son Kiram as Alam's designated heir. An earlier letter, quoted below, plays up the disagreement amongst the kadatuan and builds a case for the imminent claim by Kiram in her letters sent a few days later:

In the evening of Thursday the 7th day of the month of Jumadil, Awwal, year 1298 [6 April 1881] in the era of His Royal Highness, Sultan Muhammad Jamalul Alam, the people of the forests and waters came into a meeting, especially the datus up to the appointed ones including Panglima Adak and Ulangaya Digadung and the Chinese Mandarins. And the datus like Datu Dakula, Datu Puyu, Datu Muluk, Datu Kamsa, Datu Piyang, Datu Buyung, Datu Hasim, Datu Jamahali and the ordinary people were in chaos. There was no agreement. There was no one to replace the son, the Royal Highness Datu Muhammad Badaruddin as Sultan this time… (Tan Reference Tan2005a: 267)

The governor, however, seemed to concur with the majority of datu, who supported the Raja Muda, putting the issue to rest at this point. Kiram's elder brother thus ascended the throne in 1881 (Saleeby Reference Saleeby1963: 131-132).

The sultanate's control over Luuk, however, had been slipping in the last years of Alam's reign and finally unravelled under the juvenile Badarrudin. Within days of becoming sultan, Badarrudin had to dispatch a force to Luuk in retaliation for an attack on Spanish Tiange on 10 April i.e. four days before Alam's death (Majul Reference Majul1999: 357). Despite this, a steady flow of sabilallah or suicide attackers streamed out of Luuk, with eleven attacks on Tiange in August and September 1881 (Montero y Vidal Reference Montero y Vidal1888: 590). The discord exacerbated when Badarrudin left on Hajj in mid-1882, leaving the Patikul datu Aliuddin regent in his absence. In October 1882, frustrated by an ineffectual response from Maimbung, the Spanish sent Brig. Gen. Jose Paulin to Luuk with 800 troops in an attempt to suppress the sabilallah (Saleeby Reference Saleeby1963: 134). This force was augmented by Aliuddin and Jamila contributing contingents (Montero y Vidal Reference Montero y Vidal1888: 591). This action against Luuk was to have long lasting repercussions and points to the emerging rift between charismatic leaders of the locality and their dynastic elite rivals, which was to play out later in the 20th century.

The Sulu archipelago was in tumult when Badarrudin returned from the Hajj in January, 1883. This was worsened by a lingering cholera epidemic that began the year he left. The distress of rule weighed heavily on the 20-year-old monarch, and he sought solace in opium. Badarrudin's retreat into self-indulgence wasted much of the initial prestige he had acquired as the first sultan of Sulu to travel to Mecca. When he died of cholera on 22 February 1884 his only heir was his fourteen-year-old half-brother Kiram (Majul Reference Majul1999: 358).

The 1884 War of Succession

With a second sultan dead within three years and Kiram the second successive juvenile heir, rival datu saw their opportunity to extend their influence, and Sulu was consequently plunged into conflict. To shore up her son's claim, Jamila gathered allies to proclaim Kiram's right to the throne on 29 February, and again before the Spanish on 11 March (Majul Reference Majul1999: 358). While his main weakness in 1884 seemed to be the fact that he was only fourteen years old, later accounts of Kiram point to flaws of character that may have already been apparent to chiefs who knew him personally. The 30-year-old Kiram in 1900 was described by American observers as self-indulgent and self-centred (War Department Reference War1901: 86). Majul, however, maintains that Kiram always possessed the popular support of the datu in Jolo, and that challenges from Patikul and Palawan came despite this (Majul Reference Majul1999: 360). Indeed, emphasis on an Asian potentate's self-indulgence, vanity, and lack of intelligence was often used in colonial accounts to justify imperialist aims, and without a doubt played a role in exaggerating Kiram's negative image in western eyes, a view that may thus have entered the historiography due to the predominance of colonial sources.

Three days after Jamila's 29 February proclamation of Kiram, however, chiefs from Parang and Luuk convened in Patikul to advance the more experienced datu Aliuddin, who had recently served as regent during Badarrudin's absence (Majul Reference Majul1999: 358). Kiram thus seemed positioned to represent his family's pursuit of dynastic succession, whereas Aliuddin seemed to embody the kadatuan's long standing preference for demonstrated prowess. The new Spanish Gov. Parrado suggested a regency by Aliuddin over Kiram, until the youth gained maturity (Saleeby Reference Saleeby1963: 137). Aliuddin, however, was the grandson of Shakirullah, who ruled as sultan from 1821 to 1823, and actually had a claim to the throne that predated the young Kiram's (Saleeby Reference Saleeby1963: 137). Alternately, from Maimbung's perspective, Parrado's proposal usurped Jamila's desire to serve as regent to her own son. This polarized the archipelago, with local datu having to choose between factions. This triggered a provocatory campaign of cattle raiding and ambuscades (Saleeby Reference Saleeby1963: 137). Jamila eventually managed to rally more datu to Kiram, and Aliuddin was left increasingly isolated with only 800 men. Outnumbered by Kiram and Jamila's forces, he was eventually defeated at his kuta (fortress) in Patikul after which he retired, for the time being, to a nearby island (Saleeby Reference Saleeby1963:138).

Preferring a more pliable monarch, however, a new governor, Gov. Juan Arolas tried to stir the pot in 1886 when he elevated datu Harun al-Rashid of Palawan. Harun had been friendly with Manila since Alam's reign, having played a key role in convincing that sultan to accept the peace treaty of 1878. Arolas proposed that Harun serve as regent for the young Kiram, and ordered the two to Manila to submit to the Queen of Spain. While Harun was amenable, Kiram's faction refused to go to the Philippine colonial capital. Jamila once again was being spurned as regent for her son, and memories of Sultan Alimuddin in 1748 still caused consternation, who being the last Sulu ruler invited to Manila, was ultimately betrayed and imprisoned (Majul Reference Majul1999: 19). Harun was the only one to appear in Manila, and was accordingly proclaimed as sultan by Arolas on 24 September 1886 (Saleeby Reference Saleeby1963: 139; Montereo y Vidal Reference Montero y Vidal1888: 697). A few weeks later, Harun landed in friendly Parang with an escort of 200 Spanish troops to combine with the warriors of local datu Panglima Dammang. The island of Jolo was once again plunged into war.

Observing these developments, a re-emboldened Aliuddin returned to Patikul where he reunited with Kalbi and Julkarnain to re-start his own campaign (Saleeby Reference Saleeby1963: 140). Parang, Patikul and Maimbung thus each had a candidate for the sultanate in 1886, and this configuration of the factions in Sulu would have violent reverberations lasting well into the first decade of American rule 20 years later.

Maimbung was first to attack the Parang-Spain alliance, with 3000 men investing colonial Tiange in February 1887 (Saleeby Reference Saleeby1963: 140). This assault, however, was repulsed, and Harun and Arolas retaliated with a siege of their own on Maimbung on 16 April. With 850 colonial troops attacking at night by land, and Harun's men pinning Kiram's boats down at sea, Maimbung's two kuta were captured and razed. Jamila evacuated to a nearby mountain with her son and 2000 followers.

Parang and Manila then turned on Patikul, occupying it in May, forcing Aliuddin, Kalbi, and Julkarnain to reluctantly accept Harun. They quickly reneged on this, however, and Harun and Arolas attacked them again at the end of 1887, forcing the Patikul trio to flee to nearby islands. At this point Aliuddin had finally had enough, and abandoned his claim early in 1888 (Majul Reference Majul1999: 361-362). Tiange had less luck with Jamila, whose continued case for her son gained the support of much of the kadatuan in the interior of Jolo island (Saleeby Reference Saleeby1963: 142-143). In the meantime, Arolas and Harun shifted tactics, focusing on the subjugation of peripheral datu in surrounding islands to gradually weaken Kiram (Saleeby Reference Saleeby1963: 142-143. It was clear, however, that Arolas had the upper hand over Harun, as the message below suggests. While Harun's reference to Arolas as his ‘brother’ suggests nominal equality, he was quite dependent on Spain logistically, and this was to have negative consequences on his popularity with the kadatuan:

This is a letter of your brother, His Royal Highness, Commander of the Faithful, Sultan in Sulu, who is in Palawan, Muhammad Harun al-Rasid, to my brother, His Excellency [Señor], Governor, Captain General of all the Philippines. I appeal to my brother if it is possible for you, a brother of mine, to assign Sergeant Mungus in this island to take care of the affairs of the prisoners… (Tan Reference Tan2005a: 125)

A subsequent letter reveals Harun's frustration with his waning support amongst the Tausug, and his increasing reliance on Spanish power as he makes another appeal to the governor for things as mundane as staffing in his entourage:

I wish to inform my brother [the governor] concerning the welfare of the Sulu community for which I was entrusted by the sovereignty of Spain and its security here…Indeed I really found pain from the conduct and activities of the people of Panoy, the interpreter of the government in Sulu and Jaji, a Counselor who does not perform his responsibilities. What they want is to destroy me and to lower the dignity of my race. They spread rumor among the people that I am a messenger without recognition and not worthy of respect. (Tan Reference Tan2005a: 227)

While contests for succession had occurred previously in Sulu, this succession crisis was lengthy, as coastal raids, kuta battles, and sabilallah attacks between rivals dragged on for another six years. Despite a precarious beginning, however, the defeat of Aliuddin and the growing unpopularity of the colonially pliant Harun al-Rashid meant that more datu threw their lot in with the maturing Kiram, backed by his astute mother. After ten years of hostility, Spain finally accepted the now 24-year-old Kiram in 1894 (Livingston Reference Livingston1915: 83).

Kiram became undisputed sultan a decade after the death of his brother Badarrudin. The young sultan then changed his name from Amirul to Jamalul, invoking his illustrious ancestor to further stabilise support, becoming Jamalul Kiram II. Harun-al-Rashid returned to the island of Palawan, where he had been headman, while Aliuddin quietly lived out the rest of his life in Patikul. With this long conflict so recent in the memories of the Tausug when American rule began, and with the same men and women in power in the towns around Jolo island, it is difficult to argue that the hitherto assumed ‘colonial’ conflicts that emerged in the early 20th century under the new imperialists were not in any way influenced by them.

The American ‘Faction’

This contest for power between factions remained the predominant plot in Sulu at the start of the American era. The Tausug treated Spain and subsequently the US as merely another faction amongst many, albeit with additional sources of manpower and potential prestige. Having taken the Philippines from Spain in a brief war in 1898, the Americans arrived in Mindanao and Sulu the following year, seeking to ensure the Muslim sultans of the south would not support the continuing pockets of resistance by supporters of the revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo in the north. In Sulu, the new imperialists were quickly courted by faction leaders in efforts to boost their advantage (The United States Senate 1900: 43). Although the tensions between Patikul, Parang, Tiange, and Maimbung had abated somewhat by 1899, the new American regime initially offered new opportunities for those forced to accept Kiram to rectify their circumstances. American administrators were quickly made aware of these rivalries between datu, as they were frequently courted by the factions, as the note below on Kalbi's impressions of the newcomers indicates:

[Datu Kalbi] was very glad when the Spaniards left and the Americans came here, and he hopes the governor here will watch them and see if it was true what [the sultan's] people were saying about them that they were two bad datos, and if any chief or the Sultan was fighting them that it would be investigated and seen that they should not be fought against unjustly. (The United States Senate 1900: 76)

These animosities were often dismissed and glossed over by the new regime as a complicated mix of petty rivalries—part of a context of chaos into to which they had ostensibly come to bring order. When Americans stepped into the drama aspiring to bring the factions into check, they became part of the ongoing tensions and contestations. What they saw, however, was resistance to attempts at creating order out of what they saw was chaos, or resistance to the imposition of alien forms of rule. Frustrated at the persistence of this local state of affairs, the Americans sought to blame the sultan, attributing the situation to his weakness as a ruler:

I recognize that the Sultan did his best to help us. I have so stated in my reports. But the Government in the United States has come to the idea that the Sultan is not strong enough to govern his people. Whenever a government is not strong enough to govern its own people, the government of that country has to go to someone who knows how to rule it…The United States has found that the Sultan's government is not strong enough to govern this Island. (Official Interpreter 1904a)

As a legacy of this ‘glossing over’, the contests between the kadatuan and the sultanate that stemmed from the 1880s succession crisis were likewise misunderstood by later historians as part of this state of ‘anarchy’. As Sixto Orosa suggested in 1923: “Many of the chiefs proposed to resist all interference with the old order. Every few days a juramentado was sent out on his errand of killing” (Orosa Reference Orosa1923: 32). As Americans increasingly sought to contrast their own sophistication with what they saw as Tausug primitiveness, resistance to their rule became attributable to an overall suspicion of modernity possessed by the less-civilized. Indeed as Hawkins explains: “…American ethnologists and military officials methodically constructed an academically defensible anthropological image of the Moro as a noble, primitive warrior, bursting with evolutionary possibilities” (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2013: 20). Authors would often present a narrative of old versus new in characterising the period as a clash between the expiring world of the Tausug datu and the emerging world of the modern American colonial state. This approach would often overlook or marginalise the importance of any local inspiration for the disorder (Abinales Reference Abinales2004: 46).

The early years of conflict under American rule, this paper argues, were not standalone reactions to a new ruler arising from a rejection of US modernity, but a continuation of Tausug contestation that had their roots in the succession crisis of 1881. It was Maimbung that first opened up to negotiation with the Americans and signed the Bates Treaty of 1899, mirroring the role Parang had previously played with Spain. The lingering animosities from almost ten years of prior conflict did not take long to manifest. Relations between Maimbung and Patikul soured again in the wake of a failed venture between Kalbi and Kiram to collect taxes from the island of Siasi. This endeavour only resulted in Kalbi complaining that he had paid for the expenses of the expedition without seeing the returns promised by the sultan (The United States Senate 1900: 43). However, a subsequent incident in 1900, where a tribute of pearls from South Ubian traditionally owed to the sultan was sent instead to Kalbi, became the tipping point. With the tribute to Kalbi being a reminder of Kiram's recently precarious position on the throne, Kiram reacted swiftly, resulting in open conflict ensuing for the first time under the American watch. A detachment of the sultan's forces, with allies from Tandubas, attacked five fortified stone kuta defended by 2500 Ubians. The bewildered Americans had to broker peace, compelling Patikul to publicly accept Kiram for a second time in less than ten years. This was also the fourth time Patikul had lost a challenge to the sultanate in the span of sixteen years.

But even this was only a temporary respite. In July 1900, a datu from Parang, Panglima Indanan was convinced by Jamila to make a display of arms in support of Kiram. Indanan, however, was blockaded from delivering his men by a Patikul ally named Panglima Tahir, who was then vying with Indanan for local supremacy. The previous chief, Maharajah Towasil, died without an heir in 1901 and Parang consequently descended into a contest for power between Indanan and Tahir (Official Interpreter 1901). Parang, therefore, was split between two datu allied to two different sides in the succession crisis of 1884 (Livingston Reference Livingston1915: 88). The area consequently descended once again into provocatory cattle raiding, as chiefs postured with each other for local supremacy. The increased cattle raiding in that locality exasperated the American military governor of Sulu, William Wallace, who in 1903 wrote:

Maharajah Indanan is strong and bad—his people steal cattle horses and slaves— lives six miles south of Jolo [Tiange]. Indanan's people swarmed around three troops of dismounted cavalry commanded by Capt. Elting. (Wallace Reference Wallace1903c)

The early confrontation between Indanan and Elting's detachment of US troops in 1903 certainly did nothing to alleviate the negative impression the Parang chief made on the Americans (Wood Reference Wood1903b). Yet Indanan's targets were not merely random victims, as they were members of a rival alliance group, and were closely associated with Kiram of Maimbung. The contestations within Parang increasingly entangled parties further afield as we have seen in Maimbung and in Patikul. While this would eventually be resolved in favour of Indanan, events in Parang would nonetheless draw players in from the rich, populous, and troublesome region of Luuk.

Biroa of Parang and Hassan of Luuk

On 26 June 1903, Tahir's son Biroa killed a man in Parang and kidnapped the dead man's daughter. While Wallace wanted Indanan to ‘arrest’ Biroa (Wallace Reference Wallace1903b), Indanan thought Biroa was justified since the victims turned out to be his own slaves (Indanan Reference Indanan1903). Biroa took advantage of this hesitation and retreated with his father to a kuta in sympathetic Parang and there prepared to resist (Scott Reference Scott1904a). Wallace's verbal pressure on Indanan, and ultimately Kiram, was ineffectual, as months passed without any action. Relieving Wallace at the end of August, Major Hugh L. Scott, the new district governor, saw little change and renewed pressure on Kiram before his own datu in much less diplomatic fashion:

The Sultan and ministers were in the Headquarters’ [sic] building at Jolo and the Sultan was asked point blank whether or not he intended to obey the orders to get Biroa; he replied; I don't [sic] know. He was then given 3 minutes by the watch to find out whether he would or not, with the understanding that, if he concluded not to, at the end of that time, he would not be permitted to leave the building. In a minute and a half he promised obedience… (Scott Reference Scott1904a: 3-4)

Tensions took a serious turn on 6 October 1903, when Julkarnain and Indanan accompanied the Luuk datu Panglima Hassan and 2000 armed men to the outskirts of Tiange. Hassan was the most powerful chief to refuse to take action against Biroa, declaring from Luuk that “If a Moro cannot kill his slaves then what can he do?” (Scott Reference Scott1904a). Indeed, Wallace once reported that: “…if [Hassan] were Sultan, he would rule” (Wood Reference Wood1903b). He would become Sulu's prime ‘outlaw’ as a consequence. Luuk had supported Patikul and Aliuddin against Kiram in the 1880s, and it was inevitable for Maimbung to see Hassan as a potential threat. It would have served many a datu's interests to have the Americans turn against and weaken Hassan. Indeed, other Tausug datu seemed to be egging him on in confronting Kiram and the Americans. In fact, there are suggestions that there was intrigue involved in bringing Hassan to the fore.

After several days of parlaying at Tiange, Hassan was apparently promised an agreement of mutual defence in secret by Parang and Patikul, should any of them be attacked by Kiram or the Americans (Official Interpreter 1904b). Later accounts suggest that the Patikul and Parang datu were positioning Maimbung and their allies the Americans to act against Hassan. Indeed, when colonial troops finally did enter his territory, the supposed allies did nothing. With the Parang, Luuk, and the Patikul datu uncooperative, Scott sent his own troops after Biroa, who was fortified in his kuta near Parang.Footnote 2 After being surrounded, Biroa surrendered peacefully on 22 October 1903, and was punished according to Tausug customary law, which involved paying a fine (Scott Reference Scott1904a).

With Biroa's capture, the attention now shifted to Hassan. Eight hundred American troops assembled at Tiange, with Parang bringing 2000 men and 300 boats in contradiction to its promise to defend Luuk (Scott Reference Scott1904b). It seems that Hassan's enemies, who included Indanan and Kiram, may have sought to isolate him and Luuk in order to get Americans to eliminate him. Hassan's forces were decimated at a fortress called Pang Pang and although he managed to escape the destruction, without a force to fight with, there was no choice but to go into hiding. Wood and Scott were relentless in pursuit, staying in the field for weeks at a time, ravaging the interior of Jolo. With strife and fear deep in the countryside for an extended period, this was quite unlike the Spanish way of war that the Tausug had come to know, whose tactics were more tentative—staying close to the coast and retreating to Jolo and Zamboanga shortly after each raid or foray. Hassan's ally Maharajah Andung was captured on 6 February 1904 after the destruction of his kuta. Hassan himself was chased through the jungles of the interior for another month before he was cornered and killed with his remaining followers in a small crater (Scott Reference Scott1904b) on Bud Bagsak, an extinct volcano in central Jolo on 4 March 1904 (Scott Reference Scott1904c).

Laksamana Usap

Hassan's mantle in Luuk was passed to his lieutenant, Laksamana Usap. Usap was an enigmatic figure, with contradictory reports explaining the reasons for his assumption of Hassan's role. He was not a principal chief like Hassan, nor did he enjoy the wider support of the kadatuan of Luuk that his predecessor had. Usap allegedly did not want to fight the Americans, but was fearful of the shame and punishment that he would be subjected to (Official Interpreter 1904c). It was also suggested that Usap did not want his kuta to come into the possession of the Parang chiefs, indicating the influence of that region's conflicts on Luuk (Official Interpreter 1904b). Another report suggested Usap was fighting because his daughter was killed in one of the battles against Hassan (Official Interpreter 1904d). Considering the submission and shame being inflicted by the Americans on recalcitrant Tausug, which often involved humbling oneself before the other datu—Usap's peers—it is likely that Usap felt there was no honourable way out of his predicament apart from fighting to the death—as a sabilallah akin to many of those emanating from Luuk in the 1880s.

Growing terror and suffering in the countryside coincided with Usap's plight, and compelled many to join him, as he was already the focus of American ire (Livingston Reference Livingston1915: 101). The emerging hysteria produced wild rumours ranging from the imposition of taxes on coconuts and women (Scott, n.d.), to paranoia about Americans poisoning the food and water to cause cholera (Wallace Reference Wallace1903a). These fears were possibly reinforced when the colonial regime attempted to impose policies such as the head tax or cedula in early 1904. With rice in short supply due to the cholera and ongoing violence since May 1903, the people who had gathered around Usap were largely refugees from the countryside. Usap at one point had approximately 400 men and women in his kuta by late 1904 (Livingston Reference Livingston1915: 101). While many were convinced by Scott and Kiram's agents to return to their homes, 100 loyalists remained when colonial troops, anxious at the potential for broader unrest such a large congregation of upset natives could cause, attacked on 7 January 1905. Usap was found dead amongst his remaining supporters save seven, who had surrendered (Livingston Reference Livingston1915: 102).

Usap's plight, while representing a turn toward charismatic leaders in the shifting configurations of conflict in Sulu, is nonetheless not a new phenomenon spawned by the advent of American rule. Rather, it was linked to the chain of animosities between Luuk, Parang, Patikul, and Maimbung, triggered by Alam's death in 1881. Patikul's quarrels with Kiram, rooted in the aftermath of that year, guided the initial alignments in 1903. Kiram's and Indanan's longstanding distrust of Luuk and their manipulation of circumstances led the unsuspecting Americans to eliminate a leader who was perceived by rival datu as a powerful obstacle against their own ambitions, but who may not actually have been fully opposed to American rule, as we shall see in the following section of this paper. In the process, the destruction and devastation in the countryside resulting from the escalation of conflict, created an environment of popular terror that led desperate rural Tausug to seek refuge on mountain tops and in kuta. These concentrations of rural refugees inevitably made American authorities uncomfortable, and led to repeats of the Usap episodes at the massacres of Bud Dajo in 1906 and Bud Bagsak in 1913.

Intrigue against Luuk

As Panglima Hassan, and Laksamana Usap after him, ruled over what was understood to be the most powerful and populous district on the island of Jolo, neither Parang nor the sultan in Maimbung seemed to feel that they were capable of dealing with him on their own. The region had historically been troublesome, having been the source of the dreaded juramentados in the 1880s, complicating the then-sultan Alam's attempts at peace with the Spaniards. Hadji Butu, Kiram's prime advisor, revealed in a 1904 conversation with District Governor Col. Hugh Scott, a few months after Usap's death, how Hassan was given false assurance by Indanan about the alliance between Kiram and the Americans:

If [the sultan] gets angry with you and wants to fight you, he will send for us Parang people, but we won't fight you; if he gets angry with us, he will send for you Look people, but you won't fight us…Let us stick together. (Official Interpreter 1904b)

Butu continues in his recounting, quoting how Kiram blamed the Luuk conflict on Indanan's intrigues:

[The Parang chiefs] must always cheat somebody…Did you help Biroa, as you said you would; God forgive you for your lies. Why did you not help him. You ought to have been arrested with Biroa, for making all that trouble. You could have done it…I am sorry that you made [Hassan] resist that way. If you had helped him, none of you would be alive now…There was not one man killed when Biroa was arrested, and here now there are a whole lot of people killed. You chiefs better take an example now and obey the orders of the Governor. (Official Interpreter 1904b)

In a 1904 conversation with Scott, Hadji Butu reinforced rumours about a plot to undermine Luuk and its leaders: “All the chiefs that came to you…They blamed the Parang people for bringing Usap into trouble. Usap had submitted to the Sultan, they said, and the Parang people wanted to fight him yet”. Scott in fact acknowledged that he had heard this rumour several times previously: “I have heard that time and time again. What is in this?” (Official Interpreter 1904b). It was further alleged that Usap would have surrendered to the sultan had the Parang people accompanying the American troops sent out to arrest him withdrawn. In the end, it was believed that Usap chose not to surrender because he thought the Parang people would capture his kuta (Official Interpreter 1904b).

The Patikul chiefs were not blameless either in creating intrigue. In January 1902, Julkarnain spread an early rumour concerning an American expedition to Luuk whose alleged aim was the destruction of the district. The sultan had to make counter-efforts to clarify the issue with the people of Luuk, requesting Hassan hear his assurances at Maimbung. Hassan had later confirmed that he was told of an aggressive American foray into his territory, resulting in the early anxiety and distrust toward Scott and the Americans (Kiram Reference Kiram and Jamalul1902).

Hassan reportedly became quite disrespectful toward Kiram, associating him with the American regime. Sulu Gov. Hugh L. Scott noted in a 1904 report that the panglima had been known to tell the sultan directly to “shut up” (Scott Reference Scott1904a). Hassan also became notoriously difficult to get in touch with. In a letter to Scott in 1903, the Governor of the newly formed Moro Province, Leonard Wood, implies that Hassan had not been receiving messages from the colonial government. In fact, it was the Luuk chief's frequent non-appearance before American authorities that was to drive the new regime's frustration with him, as they came to interpret his inaction as defiance.

On the other hand, as a result of the false assurances from Parang and Patikul, Hassan may have gained enough confidence to believe that he could successfully defy and defend himself against an unfit sultan and what he saw as a potentially aggressive American regime based in Tiange (Official Interpreter 1904b). What this implies is that Hassan may not have wanted to confront the Americans directly at all, and was manipulated into doing so by rival chieftains. These circumstances further complicate the longstanding but rather two-dimensional image of Hassan as a rebel against foreign rule. Indeed, in 1995 Nasser Marohomsalic described Hassan along these nearly mythologised terms:

Nevertheless, it could be said that [Hassan] hated the Americans as much as he hated foreign rule. Whatever he was, Panglima Hassan was a patriot first and foremost who curved the name in the flame of his passion for freedom and by the swish of his kris on the flesh of those foreign white men who came to conquer their race. He became the rallying symbol of Tausog [sic] defiance against American presence in Sulu. (Marohomsalic 1995: 124)

Oral histories about that era, which are still sung in Sulu, also reflect a two-sided, largely local vs. outsider dynamic:

In reality, it took a mix of plotting rooted in the 20-year-old rivalries between Tausug factions, and an anxious and still tentative American regime in Sulu, to produce the stubborn rebel leaders of Luuk that would eventually define the conflicts of that era for many historians.

Conclusions

A historian of the southern Philippines recently exclaimed that the turn of the 20th century and the arrival of the American regime was: “…the most critical period in the Filipino Muslims’ modern history” (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2013: 5). Indeed, how Americans subsequently articulated Moro identity during this period proved to have a profound impact on how Muslim Filipinos themselves constructed their own nationalism. But if we remove the superimpositions of late 20th century nationalist narratives, we can see that the outbreak of conflicts between 1900 and 1905 was not just a reaction to a new overlord, but a broad continuation of the patterns of local contestation that had their roots in Tausug crises and contestations in the 19th century. A long look at the circumstances in Sulu, extending from the death of Alam in 1881 to the neutralization of Luuk in the first years of American rule reveals two things: First, despite the persistence of an epoch-making colonial narrative, the Americans in many ways simply stepped into a set piece role played in previous decades by Spain, in a bigger game largely defined by the Tausug. Secondly, locality-driven rivalries, epitomized by the plots against the Luuk chiefs by decades-old factions led by Sultan Kiram II at Maimbung, Indanan at Parang, and the brothers Kalbi and Julkarnain at Patikul, were the engines that drove events at the beginning of the 20th century. Thus, the narrative in Sulu was not driven merely by reactions to the nascent and still limited American regime nor the Spanish one they replaced. Rather, the predominant event that the Tausug seemed to have been reacting to over the course of two decades was the death of Sultan Jamalul Alam in 1881. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Sulu was in the midst of monumental changes driven by forces from within its own society, and while this was certainly affected by colonial activities, it was by no means defined by them to the extent previously suggested in the historiography.

While Sulu may only be a small part of Southeast Asia, and indeed, a miniscule part of the American empire of the late 19th century, its story reminds us that agents of many other empires in many other places are often one actor among many, stepping into continuing local political and social processes. In this sense the imperial role is magnified, and local processes are overshadowed. While re-contextualising a colonial empire from a local perspective can be a challenge given the preponderance of colonial sources and perspectives, it is only by doing this can we discern the truer dimensions of native roles in world history, and the limitations of imperial ones.