No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

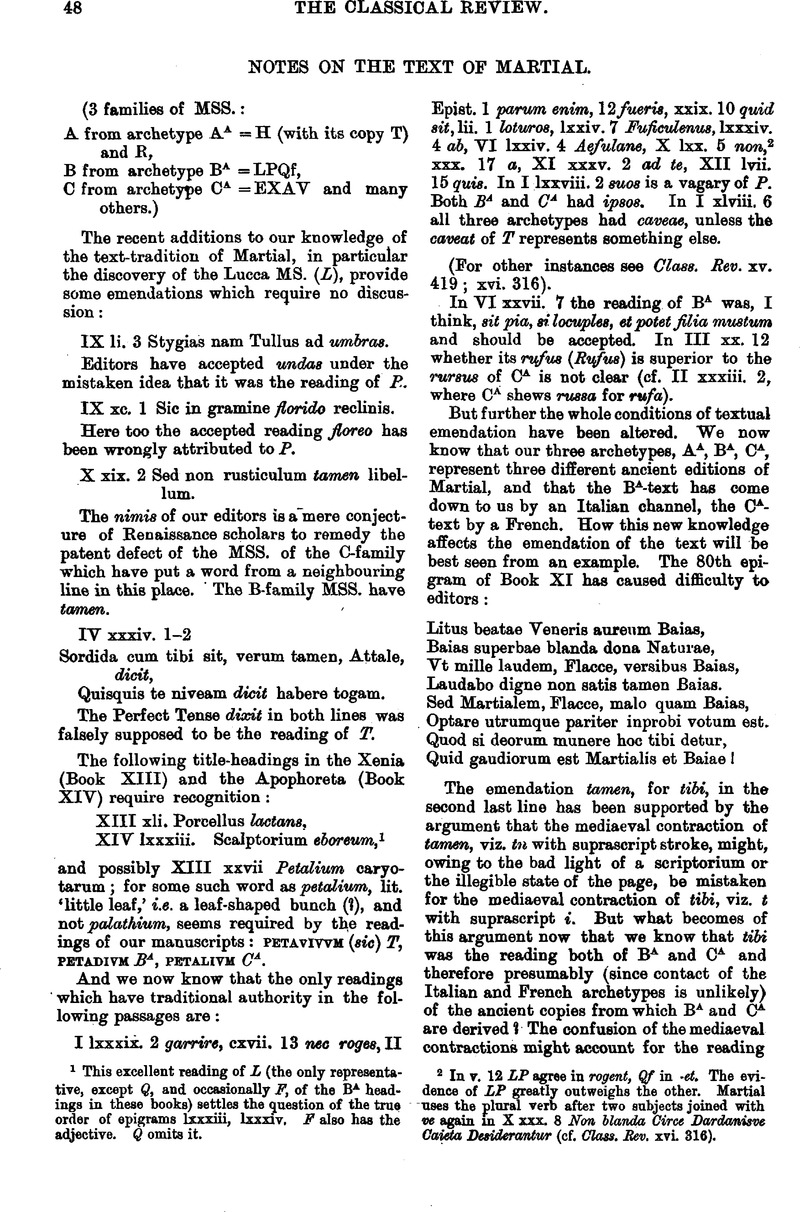

Notes on the Text of Martial

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Original Contributions

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1903

References

page 48 note 1 This excellent reading of L (the only representative, except Q, and occasionally F, of the BA headings in these books) settles the question of the true order of epigrams lxxxiii, lxxxiy, F also has the adjective. Q omits it.

page 48 note 2 In y. 12 LP agree in rogent, Qf in -et The evidence of LP greatly outweighs the other. Martial uses the plural verb after two subjects joined with ve again in X xxx. 8 Non blanda Circe Dardanisve Caieta Desiderantur (cf. Class. Rev. xvi. 316).

page 49 note 1 Friedlaender's defence of the traditional text is, however, I fancy, correct. He explains Martialem to mean, not the poet himself, but his cousin Julius Martialis, who is often referred to by this single name (V xx; VI i; X xlvii). The epigram seems to me a very cleverly worded discharge of the delicate task of suggesting to Flaccus that he should include Julius Martialis in the invitation to Baiae. In a recently published monograph (‘The Ancient Editions of Martial’—Parker, Oxford, 1902) I have tried to glean what information is available regarding the three ancient editions of the poet and the three archetypes of our MSS., and have added collations of L and E.

page 49 note 2 And a very careless copy too. Witness I iii. 5, where rhonchi (followed by a word beginning with i) was written runci or perhaps runc in AA. This appears in H as runt, but in T this runt has become fuerunt. In the Thuaneus the Epichalamium of Catullus follows immediately on the Martial extracts, and is written by the same scribe. We must estimate his value as a witness for the text of Catullus from his testimony to the text of Martial. For example, he seems to have found a difficulty with the unfamiliar abbreviations of quae (que) and qui in his original. The Thuaneus spelling in v. 12 of the Epithalamium, requirunt, must not be too strongly vindicated against the spelling of the other MSS. requaerunt (-que-).

page 49 note 3 The Xenia and Apophoreta, usually called Books XIII–XIV, were not excerpted in H, but transcribed in full, so much of them as remained in the archetype.

page 49 note 4 That the book was smaller than Book I I infer from I xliv, which surely contains a reference to the Spectacula as ‘charta minor’ (i.e. liber chartaceus minor), contrasted with Book I (cf. vi, xxii), which is called ‘charta maior’: Lascivos leporum cursus lususque leonum Quod maior nobis charta minorque gerit Et bis idem facimus, nimium si, Stella, videtur Hoc tibi, bis leporem tu quoque pone mihi. The poem on the lion and the hare in the Spectacula has not been preserved. I xlv is another reply to the same charge of repetition. Martial ‘more suo’ is paving the way for a reiteration of the same offence (cf. xlviii, li, Ix and, more remote, civ.) The content of the page of AA seems to have been some thirty-six lines. At Spect. vi. 6 and vii. 7 are two defective lines: hoc [et] iam feminist and denique supplicium. It is natural to refer them to the same hole in the parchment of AA, and to guess the size of the interval which originally separated them. Both fragments are in the MS:(T) represented as the beginnings of lines. This would be possible if the page of AA were written (as seems likely) in two columns. The one defective line would be in the left-hand column of a recto, the other in the left hand column of a verso. Otherwise we should be forced to regard the Jwe etiam femineo of T as, not the beginning, but the end of a line, e.g. <Quis iaculo abnuerit tal >ia femineo ?

page 50 note 1 Thus Schneidewin makes a new epigram at iv. 5, Friedlaender at xii. 7.

page 50 note 2 The Renaissance editors print vi and vib as one epigram.

page 51 note 1 The use of k (common before a, e.g. karus for carus) made the word look like a Greek word, and may have led to its inclusion in a bilingual glossary.