Introduction

Suicide is a major public health issue world-over with more than 800 000 people taking their own life and many more attempting suicide every year (World Health Organization, 2016). Also, suicide was noted as the second leading cause of death in young age group i.e., 15–29 year olds globally in 2012 (World Health Organization, 2016). Mental illnesses are important risk factors for suicidal behaviour (Baxter & Appleby, Reference Baxter and Appleby1999). Suicidal risk in psychiatric inpatients of upto 50 times higher than in the general population has been reported, with particularly higher suicide risk in patients with personality and affective disorders (Mortensen et al. Reference Mortensen, Agerbo, Erikson, Qin and Westergaard-Nielsen2000; Ajdacic-Gross et al. Reference Ajdacic-Gross, Lauber, Baumgartner, Malti and Rössler2009). Different recent studies have reported inpatient suicide rates varying between 70 and 270 per 100 000 psychiatric admissions (Deisenhammer et al. Reference Deisenhammer, DeCol, Honeder, Hinterhuber and Fleischhacker2000; Powell et al. Reference Powell, Geddes, Deeks, Goldacre and Hawton2000; Dong et al. Reference Dong, Ho and Kan2005; Neuner et al. Reference Neuner, Schmid, Wolfersdorf and Spießl2008; Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Agerbo, Mortensen and Nordentoft2012). Suicide risk was also noted to be more both immediately after admission and immediately following discharge and as well as in the case of short duration of inpatient treatment (Copas & Robin, Reference Copas and Robin1982; Rossau & Mortensen, Reference Rossau and Mortensen1997; Qin & Nordentoft, Reference Qin and Nordentoft2005; Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Bickley, Windfuhr, Shaw, Appleby and Kapur2013). It has been noted that majority of the in-patient suicides occurred at a time that was thought to have no/low risk of suicide (Dong et al. Reference Dong, Ho and Kan2005). A systematic review and meta-analysis noted that a history of deliberate self-harm, hopelessness, feelings of guilt or inadequacy, depressed mood, suicidal ideas and a family history of suicide were significantly associated with in-patient suicide. The authors suggested that development of safer hospital environments and improved systems of care are more likely to reduce the suicide than risk assessment, as predictive value of a high-risk categorisation was very low (Large et al. Reference Large, Smith, Sharma, Nielssen and Singh2011). Information about in-patient suicides is scarce from India and hence this study would add to the understanding of this serious public health issue.

Aim

The aim of this study is to assess the socio-demographic and clinical profile of psychiatric in-patients who committed suicide during hospitalisation.

Methodology

The study involved retrospective review of medical records of psychiatric in-patients who died by committing suicide during their hospitalisation in National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), a tertiary care centre at Bangalore in India. The medical records were reviewed for 30 years’ duration from 1985 to 2014. Number of inpatients who died by committing suicide was found with the help of the medical register. Clinical details of these patients regarding multiple variables were obtained by detailed review of the medical records and assessed using a structured proforma designed for the same. The data generated by this assessment was analysed.

Variables

Variables used in this study were age, gender, education, background, socioeconomic status, diagnosis, duration of illness, stressors, duration of inpatient care, pre-morbid personality, family history of suicide, family history of psychiatric illness, past history of suicidal attempt, past history of inpatient care, history of medical illness, history of suicide discussed with at the time of admission, suicidal risk assessment, history suggestive of suicidal risk, inpatient suicidal attempt, ECT, medications used, precipitating factor, suicidal note, place, method, post-mortem finding.

Results

Socio-demographic variables

The total number of psychiatric inpatient deaths due to suicide from 1985 to 2014 (30 years’ duration) were noted to be 13. The total number of psychiatric admissions during this time period was 132 249, hence the rate of in-patient suicide in this study is around 10 per 100 000 admissions. Majority of them i.e., 53.8% (seven) belonged to the age group of 20–30 years’ age (Table 1). No suicide was noted in patients with age below 20 years. Among the in-patients who committed suicide, 84% (11) were of male gender and 77% (ten) were educated till at least secondary education, whereas two were illiterate. Sixty one percent (eight) of the in-patients who died by committing suicide belonged to urban background and 38% (five) of them belong to rural background. An important finding noted was that 77% (ten) of them belonged to above poverty line economic status, whereas 23% (three) of them were of below poverty line economic status.

Table 1. Socio-demographic variables

Clinical variables

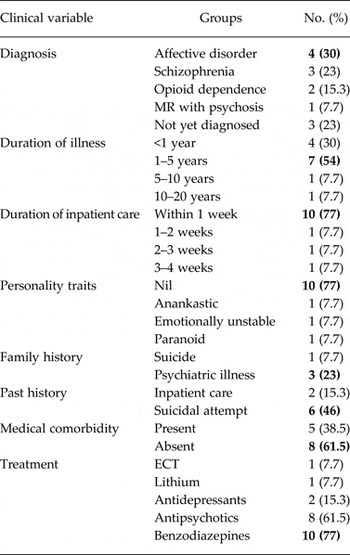

The in-patients had varying diagnoses with 30% (four) having a diagnosis of an affective disorder whereas 23% (three) were not yet diagnosed, 23% (three) had schizophrenia, 15.3% (two) of them had opioid dependence and 7.7% (one) was suffering from mental retardation with psychosis (Table 2). Duration of illness was less than 5 years for maximum number of patients − 84% (eleven). Life-events or stressors were noted in 38.46% (five) patients. Twenty three percent (three) patients were noted to have personality issues. Among the patients, 46% (six) had past history of suicidal attempt and 15.3% (two) had past history of psychiatric inpatient care. None had attempted suicide during in-patient care earlier. Family history of suicide was reported in 7.7% (one) patient, whereas 23% (three) had family history of psychiatric illness. With respect to the treatment, majority of the patients were on antipsychotics (61%) and benzodiazepines (77%).

Table 2. Clinical variables

Suicide related variables

Majority of the suicides i.e., 77% (ten) happened within 1 week of inpatient care and none happened in admission duration of more than 4 weeks (Table 3). Location of suicide – ten patients committed suicide in bathroom/toilet and one each in the ward, staircase and hospital building. Suicidal risk assessment was done for 46% (six) patients. None of the patients had left suicide note. The commonest method used for committing suicide was hanging, noted in 92.3% (twelve) patients and one patient committed suicide by self-inflicting injury to head. Post-mortem finding was available for eight patients and it was noted as death due to asphyxia for all of them.

Table 3. Suicide related variables

Discussion

This study was a retrospective data analysis of case records and it has given valuable information as it studied data of 30 years’ duration, which is a fairly long duration. The prevalence of in-patient suicide in this hospital in India (10/100 000 admissions) is less as compared with the data reported from other countries (70–270/100 000 admissions) (Dong et al. Reference Dong, Ho and Kan2005). It is also little less than the prevalence noted from another Indian hospital (20/100 000 admissions) and the age-standardized suicide rate in India (21/100 000 in 2012) (World Health Organization, 2014; Bose et al. Reference Bose, Khanra, Umesh, Khess and Ram2016). It may not be possible to deduce the factors involved in this difference from the current available data. Yet the possible protective factors against suicide may be the hospital policy of compulsory presence of family member with patient during in-patient stay, avoiding authorised leave for patients during in-patient care, provision of primarily shared accommodation facility for in-patients, which reduces chances of patients being alone and increases probability of social interaction, this also helps in observation of any behaviour or tendency for self-harm by multiple individuals who can alert the family member or health professionals to avoid such behaviours in future.

Majority of the patients belonged to age group of 20–30 years similar to finding from another Indian study with mean age of 25 years (Bose et al. Reference Bose, Khanra, Umesh, Khess and Ram2016). This is important in the context of World Health Organization's observation of suicide being second most common cause of death in age group of 15–29 years. Findings are differing in some studies such as in one study median age was 39 years and in two studies the mean ages were 45 and 49 years (Deisenhammer et al. Reference Deisenhammer, DeCol, Honeder, Hinterhuber and Fleischhacker2000; Meehan et al. Reference Meehan, Kapur, Hunt, Turnbull, Robinson, Bickley, Parsons, Flynn, Burns, Amos, Shaw and Appleby2006; Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Hu and Tseng2009). In the current study, many patients were well educated (studied till graduation) similar to another study (Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Agerbo, Mortensen and Nordentoft2012). Most of the patients who committed suicide were males (84.7%) similar to 90% reported by Bose et al., whereas a meta-analysis did not find male gender to be significantly associated with in-patient suicide while it is being a known risk factor for suicide in community (Large et al. Reference Large, Smith, Sharma, Nielssen and Singh2011). With respect to the financial status, most of the patients (77%) were belonging to above poverty line status, whereas in other studies the rates of suicide were higher with poorer population, similar to the findings in community population (Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Agerbo, Mortensen and Nordentoft2012; Bose et al. Reference Bose, Khanra, Umesh, Khess and Ram2016).

Common psychiatric diagnosis of people who completed suicide was affective disorders and schizophrenia, which is noted in other studies as well (Proulx et al. Reference Proulx, Lesage and Grunberg1997; King et al. Reference King, Baldwin, Sinclair and Campbell2001; Large et al. Reference Large, Smith, Sharma, Nielssen and Singh2011; Bose et al. Reference Bose, Khanra, Umesh, Khess and Ram2016). A noticeable finding here is that three patients were mentioned as ‘not having any diagnosis yet’, which may be due to mixed symptoms or possible prodromal features. Most of the suicides (84.7%) happened in people with illness duration within 5 years, with 30% happening within 1 year of onset of illness similar to another study (Dong et al. Reference Dong, Ho and Kan2005). A study has also found that a short length of illness (less than 12 months) was independently predictive of suicide in the immediate admission period (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Bickley, Windfuhr, Shaw, Appleby and Kapur2013). First week of inpatient care was the critical period with maximum (77%) suicides happening during that phase, similar to reports from multiple studies (Proulx et al. Reference Proulx, Lesage and Grunberg1997; Dong et al. Reference Dong, Ho and Kan2005; Qin & Nordentoft, Reference Qin and Nordentoft2005; Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Agerbo, Mortensen and Nordentoft2012). Some studies have reported suicides to have occurred after many days on in-patient treatment as well (Deisenhammer et al. Reference Deisenhammer, DeCol, Honeder, Hinterhuber and Fleischhacker2000; Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Hu and Tseng2009). Around half of the patients had past history of suicidal attempt, which is an important predictor of suicide attempt in general population as well as in-patients (Large et al. Reference Large, Smith, Sharma, Nielssen and Singh2011; Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Agerbo, Mortensen and Nordentoft2012; Bose et al. Reference Bose, Khanra, Umesh, Khess and Ram2016). Past history of in-patient psychiatric care was found in only 15% of cases, whereas it was 68 and 76% in other studies (Dong et al. Reference Dong, Ho and Kan2005; Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Agerbo, Mortensen and Nordentoft2012). Suicidal risk assessment was done in half of the people and this suggests that others were possibly considered to have low risk of suicidal behaviour, similar finding is noted in other studies also (Dong et al. Reference Dong, Ho and Kan2005; Meehan et al. Reference Meehan, Kapur, Hunt, Turnbull, Robinson, Bickley, Parsons, Flynn, Burns, Amos, Shaw and Appleby2006).

Hanging was the method opted by majority of them, which is similar to many other studies, and the incident site being bathroom or toilet (Proulx et al. Reference Proulx, Lesage and Grunberg1997; Meehan et al. Reference Meehan, Kapur, Hunt, Turnbull, Robinson, Bickley, Parsons, Flynn, Burns, Amos, Shaw and Appleby2006; Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Agerbo, Mortensen and Nordentoft2012; Bose et al. Reference Bose, Khanra, Umesh, Khess and Ram2016). This could be due to comparatively easy accessibility to hanging in an inpatient setting. Whereas some studies have mentioned violent methods such as jumping from height (studies from China and Taiwan), jumping in front of a vehicle (Austria) and drowning (UK) as common methods of inpatient suicide (Deisenhammer et al. Reference Deisenhammer, DeCol, Honeder, Hinterhuber and Fleischhacker2000; Powell et al. Reference Powell, Geddes, Deeks, Goldacre and Hawton2000; Dong et al. Reference Dong, Ho and Kan2005; Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Hu and Tseng2009). With respect to the location, in this study all the 13 patients had committed suicide in the hospital building whereas many studies have reported high occurrence of suicide of in-patients outside hospital premises during agreed leave or by absconding (Proulx et al. Reference Proulx, Lesage and Grunberg1997; Deisenhammer et al. Reference Deisenhammer, DeCol, Honeder, Hinterhuber and Fleischhacker2000; Powell et al. Reference Powell, Geddes, Deeks, Goldacre and Hawton2000; Dong et al. Reference Dong, Ho and Kan2005). Thus, the in-patient suicides in this study have some variations as well as some similarities in terms of the clinical profile as compared with other studies.

Limitations

The study is based on the data available from case-registers is retrospective and hence has its limitations. Being retrospective study the clinical assessment information may be less detailed as compared with the prospective data collection. Patients, who may have absconded from the hospital and committed suicide outside the hospital, may not have been reported to the hospital authorities and hence may be missed. Otherwise an in-patient suicide being major hospital occurrence, it is unlikely that any in-patient suicides were missed. The study findings cannot be generalised to other countries and to some other hospitals in India due to differences in health care systems as well as hospital related factors. Clinical details about course in hospital were not assessed. The prevalence is given per 100 000 admissions and not per 100 000 patients admitted due to unavailability of the data. No associations can be derived from the data as the prevalence noted is very low and hence the further statistical analysis is not feasible. Yet the study re-emphasises the factors involved in in-patient suicide and is beneficial in understanding and possibly preventing them in clinical practice.

Conclusion

Inpatient suicide despite having a low prevalence is a major challenge for doctors, allied staff and hospital administration. Along with the loss of lives and trauma to the caregivers, it can have significant psychological consequences on the healthcare professionals as well. Regular review of hospital safety measures and design, encouraging stay of relatives with in-patients, trying to avoid authorised leave during the hospital stay in patients with high suicidal risk and regular suicidal risk assessments can possibly be some of the strategies to reduce the suicidal risk. Further similar studies as well as studies assessing suicide prevention strategies in hospital setting would enhance our ability to deal with the risk of in-patient suicides.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None