In 2011, we developed an ambitious plan for assessing the impact of introductory political science courses at the University of Mississippi. We were interested in measuring whether completing such a course helped students become “effective citizens”—a stated goal of the political science major at our institution. We decided that foundational introductory courses—which are popular for fulfilling the social science general-education requirement and are taken by more than 1,000 students each semester—could be a useful indicator of whether political science (as a discipline) was meeting this core curricular objective. We chose to measure “political efficacy”—that is, an individual’s belief that he or she can affect political change—as our indicator for whether completing an introductory political science course helped students become effective citizens.

With generous support of the department chair, John Bruce, we physically distributed a panel survey to students enrolled in 17 sections of three introductory courses offered by the department: Introduction to American Politics (AP), Introduction to Comparative Politics (CP), and Introduction to International Relations (IR). In addition to questions about political efficacy, the survey included questions about background characteristics (e.g., race, gender, and parents’ level of education), political ideology, news-media–consumption patterns, and social-media usage. Additionally, because the survey was not anonymous, we could insert individual students’ end-of-semester grades as an important control variable.Footnote 1 Last, because students’ attitudes about their instructors might have an effect, we used information from end-of-semester teaching-evaluation scores as an additional control variable.

Our key findings were surprising: although we found little evidence for a gender or racial “efficacy gap” at start-of-semester, we found evidence of a significant racial “efficacy gap” at end-of-semester—in both univariate and multivariate analysis. Of course, we cannot speak to the experience of other institutions. We therefore encourage other institutions to attempt similar studies of political efficacy or other “civic” values identified as important curricular goals. We believe that departments should assess how their curriculum as a whole—rather than individual projects or pedagogies specifically geared toward “civic education”—affects students’ attitudes about American politics and its institutions.

Our key findings were surprising: although we found little evidence for a gender or racial “efficacy gap” at start-of-semester, we found evidence of a significant racial “efficacy gap” at end-of-semester—in both univariate and multivariate analysis.

POLITICAL EFFICACY, CIVIC EDUCATION, AND SOCIAL INEQUALITIES

Although few of us describe what we do as “teaching civics,” a significant part of what we do serves that function. This is most pronounced in undergraduate American government courses, in which significant attention familiarizes students with the theory and practice of America’s political system and which is one of the most common general-education electives taken by undergraduates. American political science has a history of involvement in civic education, going back to John Dewey (Reference Dewey1916). Concern with “civic” values has been a driving concern of scholars including Almond and Verba (Reference Almond and Verba1963), Barber (Reference Barber1984), Dahl (Reference Dahl1998), Putnam (Reference Putnam2001), and Young (Reference Young2002). An “institutional” phase began with the formation of the APSA Task Force on Civic Education (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1996) and the subsequent formation of the APSA Committee on Civic Education and Engagement.

We chose political efficacy rather than other values (e.g., tolerance and egalitarianism) because we believe it is a fundamental component of democracy and because it seems to be the most “content-neutral” component. Political efficacy is “the feeling that individual political action does have, or can have, an impact upon the political process…the feeling that political and social change is possible and that the individual citizen can play a part in bringing about this change” (Campbell, Gurin, and Miller Reference Campbell, Gurin and Miller1954, 187). Scholars also have long distinguished between internal and external dimensions of political efficacy (Balch Reference Balch1974; Converse Reference Converse, Campbell and Converse1972). Whereas internal political efficacy reflects an individual’s belief that he or she can understand politics, external political efficacy reflects that individual’s belief that he or she can influence political decisions.

We believe political efficacy is an important component of civic education. The most recent report by the APSA Committee on Civic Education and Engagement (McCartney, Bennion, and Simpson Reference McCartney, Bennion and Simpson2013) includes several chapters that discuss political efficacy and its relation to civic education or civic learning (see, especially, Van Vechten and Chadha Reference Van Vechten, Chadha, McCartney, Bennion and Simpson2013). However, most of the edited volume focused on deliberate pedagogical strategies, approaches, or other types of “interventions” (e.g., service-learning projects) and assessing their impact on “civic education” benchmarks or outcomes. Moreover, no chapter focused explicitly on the ways in which civic learning might vary by race or gender. The notable exception is the chapter by Owen (Reference Owen, McCartney, Bennion and Simpson2013), which included both race and gender as demographic controls in her study of whether junior and high school civic courses with “active-learning elements” improved students’ engagement with the 2008 presidential campaign.

Many elements of civic education are closely tied to political efficacy. Discussions of civic education often focus on “knowledge acquisition” (Galston Reference Galston2001; Niemi and Junn Reference Niemi and Junn2005), and there is a long-established link between education and political efficacy (Almond and Verba Reference Almond and Verba1963; Campbell, Gurin, and Miller Reference Campbell, Gurin and Miller1954). In the tradition of Dewey (Reference Dewey1916), civic-education proponents argue that increasing “political literacy” improves individuals’ political efficacy, which improves the health of our democracy (Feith Reference Feith2011; Gutmann Reference Gutmann1999; Westeimer and Kahne Reference Westheimer and Kahne2004). Traditionally, civic education includes a broad appreciation of how the political system works and how individuals can participate effectively. Studies consistently find a relationship between education and political efficacy, although that relationship is complex. Studies also have shown that deliberate “civics” instruction improves knowledge acquisition (Niemi and Junn Reference Niemi and Junn2005), as does the discussion of controversial topics (Hess Reference Hess2009). Research on political socialization has long explored the relationship between childhood and early-adult education and individuals’ political attitudes—including political efficacy (Easton and Dennis Reference Easton and Dennis1967; Meyer Reference Meyer1977). Many scholars even argue that developing or improving individuals’ political efficacy should be an explicit goal of civic education (Kahne and Westheimer Reference Kahne and Westheimer2006; Pasek et al. Reference Pasek, Feldman, Romer and Jamieson2008).

However, there is reason to be skeptical about the effects of civic education—particularly regarding deeply entrenched social inequalities such as those related to gender and race. If civic education is partly a means to impart political efficacy—the belief that one can affect political outcomes—then it must confront the realities of institutional sexism and racism embedded in American society. We know that levels of political efficacy tend to be lower among women (Verba, Burns, and Schlozman Reference Verba, Burns and Schlozman1997) and African Americans (Abramson Reference Abramson1972; Rodgers Reference Rodgers1974) and that these gender differences may be a product of socialization (Bennett and Bennett Reference Bennett and Bennett1989). Studies by the National Center for Education Statistics found that students who are poor, whose parents have less education, or are African American or Hispanic do less well on civic–political knowledge tests (National Center for Education Statistics 1999; 2007). Programs that are self-consciously oriented toward civic education must address these inequalities.

If civic education is partly a means to impart political efficacy—the belief that one can affect political outcomes—then it must confront the realities of institutional sexism and racism embedded in American society.

There is growing interest in assessing the effectiveness of civic-education programs and pedagogies. McCartney, Bennion, and Simpson (Reference McCartney, Bennion and Simpson2013) largely focused on this endeavor. However, the chapters in that volume—other than Owen (Reference Owen, McCartney, Bennion and Simpson2013) and Van Vechten and Chadha (Reference Van Vechten, Chadha, McCartney, Bennion and Simpson2013)—paid little attention to racial, gender, or other inequalities in civic education. Studies that focus on key social differences such as race and gender offer reasons for skepticism. For example, although service-learning and extracurricular programs comprise an increasing component of civic education (Baldi et al. Reference Baldi, Piere, Skidmore, Greenberg, Hahn and Nelson2001; Kahne and Sporte Reference Kahne and Sporte2008), they may not raise levels of political efficacy (Kahne and Westheimer Reference Kahne and Westheimer2006). Even if they did, students with lower socioeconomic status and ethnic minorities have fewer opportunities to participate in such programs (Conover and Searing Reference Conover, Searing, McDonnell, Michael Timpane and Benjamin2000; Kahne and Middaugh Reference Kahne and Middaugh2008). If civic education is an important component of political science curriculum in the twenty-first century, we must grapple with ways in which socioeconomic inequalities affect how students acquire the benefits of such an education, as well as the possibility that efforts aimed at civic education may have limited impact—or even negative, unintended consequences.

THE SURVEY: DATA AND METHODS

Our goal was to assess the civic-education impact of undergraduate introductory courses at our institution. Rather than develop and evaluate specific civic-education programs, we developed a panel survey of the more than 1,000 students enrolled in three introductory courses offered by the department (i.e., Introduction to AP, Introduction to CP, and Introduction to IR). We distributed our survey in two waves, during the first and last weeks of the Fall 2011 semester at the University of Mississippi, a public flagship university in the South. Although the faculty teaching the relevant courses were aware of our survey’s scope, we neither expected nor encouraged them to alter their syllabus in any way. In addition to asking questions about political efficacy, we asked about students’ background characteristics, political attitudes, and behavior. We also asked about their news-media consumption and social-media usage. Because our survey was not anonymous, we were able to match individual responses across both survey waves. This also meant that we could use students’ individual end-of-semester grades as a control variable. We collected 613 survey responses during the first wave and 444 during the second wave, which represents a 50.3% response rate at start-of-semester and a 39.9% response rate at end-of-semester. We are confident that our sample was representative relative to the total population enrolled in the three courses during that semester and the student population at large (see the appendix for more details).Footnote 2

Measures of Political Efficacy

Measuring political efficacy has a long—and contentious—history. The University of Michigan’s Center for Political Studies began studying efficacy in 1952, and every round of the American National Election Studies (ANES) survey includes political efficacy questions. There is no consensus on how to measure political efficacy. Some prefer multi-item indexes that aggregate simple agree/disagree questions, such as those developed by Niemi, Craig, and Mattei (Reference Niemi, Craig and Mattei1991). These indexes have been criticized as problematic (Chamberlain Reference Chamberlain2012), leading many scholars to prefer multi-answer survey questions, such as those used by the General Social Survey. Resolving this debate is well beyond the scope of this article; we simply sought to measure changes in political efficacy across one semester.

We asked six regularly used agree/disagree ANES questions to measure internal and external political efficacy. Our measures for internal political efficacy were as follows:

• “Voting is the only way that people like me have any say about how government runs things.” (q10)

• “People like me have no say about what the government does.” (q11)

• “Sometimes politics and government seem so complicated that a person like me can’t really understand what’s going on.” (q12)

Our measures for external political efficacy were as follows:

• “Public officials don’t care what people like me think.” (q13)

• “Those we elect to Congress lose touch with the people pretty quickly.” (q14)

• “Parties are only interested in people’s votes, but not their opinions.” (q15)

Factor analysis showed that these six items loaded on two different factors, consistent with the ANES.Footnote 3 However, covariance for external-efficacy items was smaller than for internal-efficacy items (i.e., Cronbach’s α=0.30 and α=0.60, respectively, in the first wave; α=0.31 and α=0.61, respectively, in the second wave). Thus, we are more confident in our external-efficacy measures than those for internal efficacy.

Following ANES protocol, we created additive composite indexes for internal and external efficacy. Because our questions were worded negatively, a “disagree” answer was positively associated with efficacy and coded as “1” (affirmative answers were coded as “0”). Our additive index produced a four-point index ranging from 0 to 3 for each of the two dimensions of political efficacy; higher scores indicated higher levels of political efficacy.

Student Background Characteristics

We asked students about their background characteristics: gender, race or ethnicity, birth year (age), class standing, major, political ideology, mother’s and father’s level of education, and type of hometown in which they grew up. The methodological appendix includes a table of descriptive statistics for our survey samples, as well as tests for the three variables that we used to assess the representativeness of our samples: gender, race, and class standing.

Students’ News-Media Consumption and Social-Media Usage

As part of another project on news-media consumption, we included 10 questions specifically related to news-media–consumption and social-media–usage habits. We asked about number of hours they spent watching television and using the Internet (for any purpose), how often they read newspapers or watched television news programs, and their social-media usage. We also included a guided but open-ended question asking them to list any news-media sources that they had consumed (i.e., read, listened to, or watched) during the previous week. We used those questions to construct separate news-media and social-media indexes (see the appendix).

Panel Study: Pretest and Posttest Analyses

Our survey design enabled us to use two different methods to assess the impact of undergraduate political science courses on political efficacy. First, we measured self-reported internal and external political efficacy at start-of-semester and compared differences across different gender and race subpopulations. Second, we again measured self-reported internal and external political efficacy at end-of-semester and compared differences across the subpopulations. We compared aggregate political-efficacy levels across the entire sample and subpopulations in both waves. Third, we used multivariate regression to identify independent correlates of political efficacy at start-of-semester and end-of-semester.

Because our survey was not anonymous, we could match individual student responses across both survey waves. This enabled us to measure change (as gains or losses) in self-reported internal and external political efficacy between start-of-semester and end-of-semester. Although the subsample of students who responded to both waves was smaller (N=289), it was statistically representative of our larger sample (see the appendix). Moreover, even this sample was larger than those used in published studies reporting on the civic-education effects of pedagogical strategies.

We also found little evidence that completing an introductory political science course significantly impacted students’ political efficacy—even when controlling for individual students’ grades and teacher quality.

FINDINGS

Our findings suggest that students did not have different self-reported political efficacy across background characteristics such as race and gender at start-of-semester but that a racial “efficacy gap” developed by end-of-semester. We also found little evidence that completing an introductory political science course significantly impacted students’ political efficacy—even when controlling for individual students’ grades and teacher quality.

Self-Reported Political Efficacy at Start-of -Semester

Although we observed differences in self-reported internal and external political efficacy across subgroups at start-of-semester (see appendix table 3), most were not statistically significant. Aggregate mean internal and external political-efficacy scores were 1.89 and 1.47, respectively. Students seemed more likely to believe that they could understand politics but less likely to believe that they could affect politics. We found a (weak) relationship between internal and external efficacy (r=0.22, p<0.001).

We found no significant differences in external or internal political efficacy between white and black students. We found a significant difference in internal political efficacy only across gender (z=2.17, p<0.05).Footnote 4 Not surprisingly, social science majors had higher levels of internal (z=-4.34, p<0.001) and external (z=-2.05, p<0.05) political efficacy than other majors, but there was no significant difference between first-year and other students. We found significant differences across three courses, but only for internal political efficacy. This was driven by the much lower internal political efficacy of students enrolled in an AP course (z=6.02, p<0.001).

Our survey allowed us to evaluate differences in political efficacy across other student characteristics and self-reported behaviors. Chi-squared tests revealed no relationship between mother’s or father’s level of education and political efficacy. We found a relationship between ideology and external political efficacy (χ 2=28.76, p<0.01). More conservative students were more likely to believe that they can affect politics. We also found a relationship between news-media consumption and internal political efficacy (χ 2=44.91, p<0.001) but not with external political efficacy.Footnote 5 We found no relationship between social-media usage and political efficacy.

Self-Reported Political Efficacy at End-of-Semester

By end-of-semester, aggregate political efficacy had improved (slightly) from 1.89 to 1.93 for internal and from 1.47 to 1.54 for external political efficacy; however, neither was statistically significant. We again found differences across subgroups (see appendix table 4). Social science majors continued reporting higher levels of internal political efficacy (z=-3.43, p<0.001) and first-year students had significantly higher levels of external political efficacy (z=-2.19, p<0.05) than their peers at end-of-semester. Differences in internal political efficacy across different courses also disappeared, but a difference in external political efficacy emerged between students enrolled in IR (t=-2.02, p<0.05).

Most relevant, however, was evidence of an end-of-semester racial “efficacy gap.” Black students reported lower levels of both internal (z=2.39, p<0.05) and external (z=2.47, p<0.05) political efficacy than their peers. Moreover, whereas aggregate political efficacy increased during the semester for most subgroups, political efficacy decreased among black students by end-of-semester.

We evaluated differences in end-of-semester self-reported political efficacy for other student characteristics and again found no relationship between mother’s or father’s level of education and political efficacy. This time, we found no relationship between ideology and political efficacy. We also found no relationship between end-of-semester political efficacy and news-media consumption or social-media usage. At end-of-semester, we used our institutional teaching-evaluation instrument to impute “teacher quality” but found no correlation with political efficacy.Footnote 6 Finally, the non-anonymous survey enabled us to impute individual students’ final course grades. However, we found no relationship between their grades and external or internal political efficacy.Footnote 7

Individual-Level Changes in Self-Reported Political Efficacy

Our non-anonymous panel survey also enabled us to match individual students’ responses across both survey waves. Thus, we could compare not only aggregate-level differences between start- and end-of-semester but also individual-level differences. Overall, they were small (see appendix table 5); however, some individual-level differences were significant. Students enrolled in AP reported an end-of-semester increase in internal political efficacy (z=-2.85, p<0.01). The decrease in internal political efficacy among students in CP and IR was only significant for IR (z=2.30, p<0.05). This was not surprising: because AP focuses on domestic American politics, we expected students to gain a heightened sense of political awareness. In contrast, CP and IR focus on international politics—new to most undergraduate students—and seem to leave students (slightly) less confident that they understand politics.

After finding an efficacy gap in internal political efficacy between white and black students using aggregate data, we were surprised to find no evidence from individual-level data for it. The efficacy gap in external political efficacy, however, was confirmed. On average, external political efficacy among white students increased 0.210 points (z=-3.81, p<0.001) but dropped -0.455 points among black students (z=3.50, p<0.001). We found no differences in change in external political efficacy at the individual level across other subgroups.

Again, we evaluated differences in change in political efficacy across other student characteristics. At the individual level, we found no significant difference between change in external or internal political efficacy and parents’ level of education, ideology, news-media consumption, social-media usage, grades, or teacher quality.

Multivariate Analysis of Changes in Self-Reported Political Efficacy

To account for potential interactions between our variables and political efficacy, we used “jackknife” multivariate ordered logit regression.Footnote 8 Overall, multivariate analysis confirmed many of our earlier findings but provided additional nuance; however, we note that the models were not very robust.

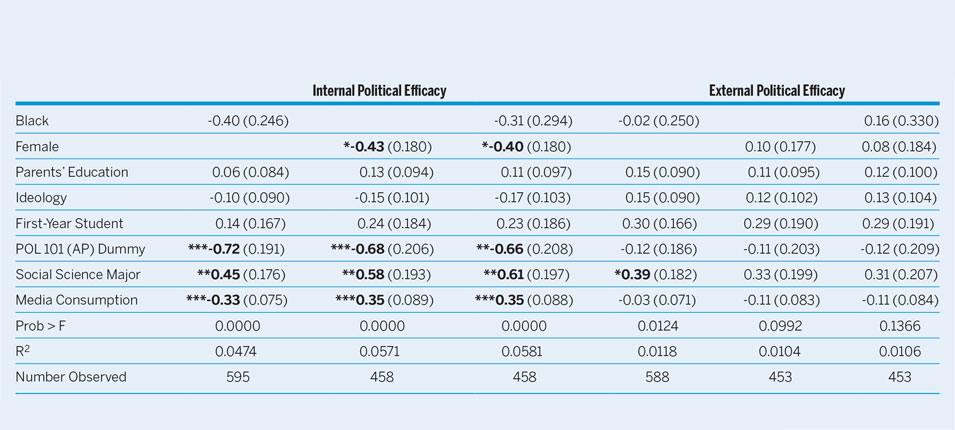

Table 1 presents regression estimates for start-of-semester internal and external political efficacy. The models for start-of-semester internal political efficacy, which were the most robust, confirmed that it was lower for students enrolled in AP and higher for social science majors, even when controlling for other factors. We found no evidence of a start-of-semester racial efficacy gap, but we found evidence that women had lower start-of-semester internal political efficacy.

Table 1 Jackknife Ordered Logit Estimates of Self-Reported Political Efficacy at Start-of-Semester

Notes: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p< 0.001. Jackknife standard-error estimates in parentheses.

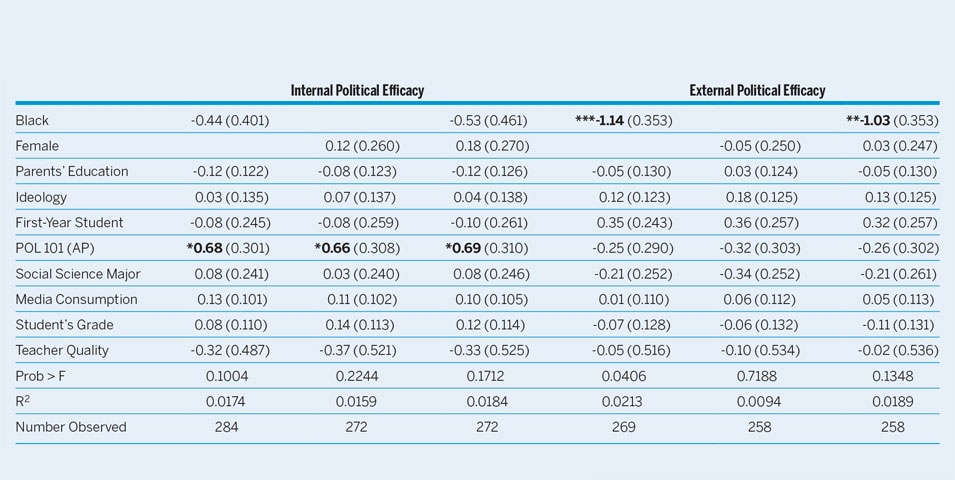

Table 2 presents regression estimates for individual-level changes in political efficacy by end-of-semester. The models confirmed the emergence of an end-of-semester racial efficacy gap, even when controlling for factors such as parents’ level of education, students’ grades, and teacher quality. We found evidence that students reported higher internal political efficacy after completing an AP course. However, these models were not robust, suggesting that other unobserved factors affect how students gain or lose political efficacy during a semester.

Table 2 Jackknife Regression Estimates for Change in Self-Reported Political Efficacy

Notes: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p< 0.001. Jackknife standard-error estimates in parentheses.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TEACHING INTRODUCTORY POLITICAL SCIENCE

Our findings raise concerns about political science and civic education. We found evidence that completing an AP course improved students’ internal political efficacy, regardless of their grades. Students who completed an AP course believed that they understood (American) politics better than they had at start-of-semester. However, we also found evidence that race is a significant factor in how external political efficacy was mediated through civic education. If external political efficacy is a measure of an individual’s belief that he or she can affect social or political change, then a racial efficacy gap is a serious concern. Moreover, we are troubled by the possibility that African American students may be leaving introductory courses with less external political efficacy than when they entered. Are black students (inadvertently or not) being taught that they have even less political power than they thought they had?

In thinking through this issue—and discussing it with colleagues at our institution and beyond—we considered two possible explanations. Some suggested that “institutional racism” is felt on campus (and in the classroom) in ways that negatively affect black students’ political efficacy. This may be a particular issue at our institution, a flagship university in the South, with all the historical baggage that that entails. It also is possible that biases (implicit or otherwise) affect black students’ reactions to faculty. We are not fully convinced by the institutional racism explanation, although we encourage more research on the subject. First, we know the department’s faculty are generally committed to racial equality and focus significant attention (particularly in AP) on discussing civil rights and liberties and social-justice movements.

Second, it seems unlikely that black students first encounter institutional racism on our campus and not previously. Recall that we observed no significant difference in start-of-semester external political efficacy between white and black students. We also were unable to fully test this explanation empirically with our data. That semester, all faculty teaching AP were white males; there were two female instructors (both in CP) and two Hispanic/Latino faculty (also both in CP).Footnote 9 Thus, we could not use instructor’s race or gender as a control variable. We also cannot identify individual students’ teaching-evaluation surveys to determine whether students’ race or gender affected instructor evaluations. We found a racial “grade gap” of 0.57 GPA points between black and white students (t=3.94, p<0.001). Again, however, black students’ external political efficacy declined even when controlling for end-of-semester grades.

The second possibility is intriguing but more difficult to test. The majority of faculty of color with whom we discussed our results were unsurprised, suggesting that a declining external political efficacy after completing an introductory course fit their own experience. They suggested that many black students arrive on campus with unrealistically heightened external political efficacy (several suggested that this reflects communities’ “empowerment” efforts) and were confronted with a more pessimistic reality in the classroom—particularly if the university was their first experience in a predominantly white institution. Those colleagues suggested that this was a typical response to completing an introductory course and that later courses reversed it, increasing external political efficacy by focusing on practical strategies rather than basic “civic” knowledge. We cannot test this claim because our data encompass only introductory courses. However, this explanation also concerns us because we know that most students who take introductory courses are not political science majors. If introductory courses “break down” the external political efficacy of black students, what happens to accounting, chemistry, and theater majors? Moreover, this explanation does little to explain the significant increase in external political efficacy of white students.

Ultimately, we have no clear, satisfactory explanation for why we observed a significant efficacy gap between white and black students who completed an introductory political science course at our institution. However, if the racial efficacy gap we observed exists, then it has profound consequences for how we think about civic education in twenty-first-century America. We encourage others to carefully consider these issues and to include race, gender, and other background characteristics in future studies of civic education pedagogies.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096518000380