When Elizabeth Garrett Anderson reflected upon the next step for medical women in the 1860s, she remarked that ‘it seemed to me that we must imperatively have a hospital entirely worked by qualified medical women before women would be trusted on a large scale by the outside public’.Footnote 1 This chapter considers the vagaries of surgical practice at the New Hospital for Women (NHW), the first female-only run institution in Britain, which grew out of the foundation of St Mary's Dispensary in 1866. From the outset, the Dispensary had a dual purpose, combining philanthropy with solid practical support for women doctors, who were exclusively to form the working medical staff. It would ‘meet a want in a large and poor district of London, and at the same time […] assist the movement in favour of admitting women into the medical profession’.Footnote 2 Between its foundation in 1866 and its transformation into the New in early 1872, the Dispensary was flooded with women both from the metropolis and from elsewhere in the country seeking the medical assistance of their own sex. The sheer demand for the services of the Dispensary, coupled with the desperate state of many of the patients, who were too ill to attend in person, and their homes too poor and dirty to permit surgical attendance, encouraged the Dispensary Committee to provide proper hospital accommodation for a new and expanded facility. While the influx of potential patients contributed to the conversion from Dispensary to hospital, the Committee noted that it was increasingly necessary, ‘[i]n very many cases’, to offer treatment that was ‘almost purely surgical’.Footnote 3 The performance of surgical procedures and the foundation of the NHW were inextricably linked in the eyes of the hospital's management and staff. As Mary Ann Elston has noted, in the second half of the nineteenth century hospitals were founded through ‘a mixture of philanthropic, professional and entrepreneurial motives’, and the New was an institution ‘where women could develop professional skills and achieve positions of responsibility from which they were otherwise excluded, both by overt opposition and by the limited mandate under which nineteenth-century women entered medicine’.Footnote 4 In a list of desirable ‘professional skills’ and in opposition to the contemporary expectations of the medical profession, surgical expertise was considered vital for the promotion of women doctors. As the first Annual Report of the hospital was so keen to publicise, successful surgery performed by skilful surgeons was a key aim of the New from its inception.

The Annual Reports listed an all-female staff, who were assisted by male consultants.Footnote 5 While the assumption was that women would carry out operations, in fact it appears that they, at least in the first decade or so of the New's existence, actually acted as assistants to the more experienced consulting surgeons. In her 1924 Reminiscences, Mary Scharlieb, who joined the New as a Clinical Assistant in 1888, made reference to the peculiarities of this situation. Discussing the operations at the hospital, Scharlieb recalled that Garrett Anderson was the

one member of the staff who undertook major surgery, it was she only who was competent, and indeed she was the only one who was willing to encounter the difficulties and responsibilities inseparable from such work. Sometimes she felt that in the interests of the patient a surgeon of greater experience ought to operate. When this occurred no self-love nor false shame prevented Mrs Anderson from inviting some outside surgeon to do what was necessary. On such occasions she played the part of assistant, and I have seen her meekly and carefully following the instructions of Sir Spencer Wells, Mr Knowsley Thornton, Mr Meredith and other consultants.Footnote 6

Scharlieb's comment is fascinating in the light of Garrett Anderson's own correspondence, which suggests that she did not consider herself a surgeon. While leaving France in 1870, Garrett Anderson remarked that she had been to the Anglo-American Hospital in Sedan, where she was ‘begged’ by the chief surgeons ‘to stay’: ‘[They] offered me as many patients I could manage entirely to myself. I was heartily sorry I could not. Tho’ surgery is not my line I should have been thoroughly glad to stay and help in that kindly stimulating atmosphere.’Footnote 7 Although she was not inclined towards surgery, the stimulation provided by the operating theatre evidently persuaded Garrett Anderson to think otherwise. With an increase in the numbers of complex surgical procedures performed in the last two decades of the nineteenth century and the growth of experimentation on the operating table, Garrett Anderson was determined to push the NHW and the cause of the woman surgeon into the forefront of developments in surgery. However, in reality, the female medical staff acknowledged their own limitations, stepping back to observe procedures rather than wielding the knife themselves.

Resignations

While the female staff remained assistants rather than operators, there was a chasm between the mission statement of the NHW and the actual practice which occurred within its walls. Although she ‘knew the limits of her training’, Garrett Anderson sought to change procedures, insisting that medical women should do the professional work of the hospital.Footnote 8 Both Louisa Garrett Anderson and Mary Scharlieb noted that Elizabeth Garrett Anderson was the only member of staff willing to undertake major surgery, and her desire to promote the cause of the female surgeon encountered numerous difficulties from her fellow medical women. Both women expressed her dedication to education through practise, but they also revealed Garrett Anderson's fear of her own surgical inadequacies; hence her willingness ‘meekly’ to assist or observe. According to her daughter, each operation caused Garrett Anderson ‘intense anxiety’, ensuring that she ‘never enjoyed operating’.Footnote 9 Too often, the reaction of the surgeon to surgical procedures is forgotten in the history of medicine; the fear and distress surgery provoked was not only that of the patients.Footnote 10 For early women surgeons, who were compelled to learn by experience, a lack of specialised training rendered every operation a risky and potentially frightening process. In a manuscript draft for a speech, Garrett Anderson remarked feelingly upon and, evidently, with personal understanding of, the effect surgery had upon the operator:

To see a skilled surgeon do his work is a very different thing from doing it oneself. […] In surgery the nerve has to be trained and that only is done by actual work of your own. I believe it is impossible for any but those who have gone through it to realise what a tremendous tax upon one's nerve it is to attempt a great operation, especially of the kind where exact previous knowledge of the difficulties cannot possibly be had. I speak of this with feeling because I know what it is.Footnote 11

From a generalised opening, Garrett Anderson's constant repetition of the personal pronoun, especially prominent in the last sentence, implied that holding ‘one's nerve’ was far from a given attribute for the surgeon. Training was essential, but when this was limited by circumstances, risks had to be taken. Behind celebration of the calm, skilful female surgeon in the New's publicity lay a more nervy reality, where ability was questioned and doubted.

If self-doubt was evident at the NHW, then resignations over the period between 1877 and 1888 revealed that concern at women performing surgical procedures was pervasive. Much has been made in previous accounts of Frances Hoggan's resignation in 1877, but other cases have been entirely passed over. Indeed, the date and circumstances of Hoggan's leaving have been confused and conflated to the extent that she appears to have resigned over operations which were not carried out until a year after she left the New.Footnote 12 Although there is indecision over when Hoggan actually left the New, there is none when it comes to why: she resigned because of controversial surgical procedures being performed by women on women.

The Minute Books of the Managing Committee, however, confirm that Frances Hoggan tendered her resignation in March 1877, giving no reason other than that she ‘had quite made up her mind to take this step’, and was emphatically ‘Resolved’ in her decision to leave. Forced, reluctantly, to accept, the Committee noted that Hoggan's ‘kind and skilful labours have done much to the raise the Hospital to its present position’, and that they felt ‘sure that the termination of Mrs Hoggan's connexion with the Hospital will be regarded both by its supporters and by the patients with general regret’.Footnote 13 The next meeting, exactly a month later, recorded Hoggan's gratitude at the Committee's praise for her support over the past five years, but also her willingness to continue working at the New on her usual Tuesdays and Fridays until they had found a replacement.Footnote 14 Examining the cases listed in the Annual Report for 1877 does not elicit any evidence of an ovariotomy, successful or otherwise, having been performed that year. In 1876, however, two operations are noted specifically, neither ovariotomies: one the repair of a recto-vaginal fistula; the other a ruptured perineum. The former failed, and the latter was postponed. One of the three deaths that year arose from complications following an operation to remove a cancerous breast. This appears to have been a tricky case, involving several operations, and resultant gangrene, which in turn led to the hospital succumbing to ‘erysipelas and some of the allied diseases’.Footnote 15 As a key member of the anti-vivisectionist Victoria Street Society and someone who appeared to ally herself with the ideas of Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman doctor to be registered in Britain, Hoggan may have objected to certain surgery involving what Blackwell labelled the ‘serious ethical danger connected with unrestrained experiment on the lower animals [which leads to] the enormous increase of audacious human surgery, which tends to overpower the slower but more natural methods of medical art’.Footnote 16 Maybe, given her political stance, Hoggan did resign over the prospect of female surgeons cutting up their own sex, or because surgical procedures, as they were carried out at the hospital, could be far too risky, as the events of 1876 revealed. But, she did not leave in 1877 because Garrett Anderson was performing ovariotomies, either on her own or with support from the consulting staff.

In fact, the first time this controversial procedure was carried out was a year after Hoggan's departure in 1878. As the Annual Report for that year trumpeted:

During the year the operation of ovariotomy has been twice performed by a member of the Hospital staff, once in private, and once in the Hospital, and in each case the patient has recovered perfectly. The Committee are not aware of this formidable operation having been ever before, in Europe at least, performed successfully by a woman.Footnote 17

If they had objected to the procedure previously, the response was not recorded, and here the only tone was triumph and pride in Garrett Anderson's achievement.Footnote 18 Even though she was not named directly, the anonymity employed served to reflect the glory back upon the New as an institution which nurtured female surgical expertise. However, in this report, the Managing Committee were also compelled to report to subscribers that, along with the departure of Hoggan, the New had lost another member of staff: John Erichsen, one of the consulting surgeons. Erichsen had been a surgical advisor to the female staff from the outset, when the hospital had been St Mary's Dispensary. After 12 years of service, Erichsen left in April 1878, according to the Minutes, but continued to ‘entertain the most friendly feelings towards the Institution’.Footnote 19 As the renowned author of The Science and Art of Surgery (first published in 1853), a well-respected and widely-used textbook, Erichsen's loss must have been a great disappointment to the New, which still needed assistance from those established members of the profession who supported medical women and the vital clinical experience they could receive at the hospital.

Erichsen had been made surgeon-extraordinary to Queen Victoria in 1876, and was Vice-President of the Royal College of Surgeons between 1878 and 1879, becoming President in 1880. Lister had been one of his house surgeons, and, as his BMJ obituary noted in 1896, he should be counted ‘among the makers of modern surgery’, with ‘his sound judgment, ripened by a vast experience, which gave him an almost unrivalled clinical insight. There was no man in the profession whose opinion in a difficult case was justly held to be of greater weight.’Footnote 20 Only three years after his resignation from the New, Erichsen publicly expressed doubts over the supposed progress of abdominal surgery. The Science and Art of Surgery raised, but did not support, objections to operations such as ovariotomy, concluding that the discomfort was worse without action and patient death rates were not so high as other procedures to warrant surgeons abstaining from the process.Footnote 21 And yet, by August 1881, in a lecture given as President of the Surgery Section at the BMA Annual Meeting Erichsen acknowledged the ‘brilliant advance’ made in abdominal surgery, but felt troubled by the increasingly alarming experimental nature of his craft:

The uterus and the spleen, the stomach, the pylorus and the colon, have each and all been subjected to the scalpel of the surgeon; with what success has yet to be determined; and it is for you to decide whether some, at least, of these operations constitute real and solid advances in our art, or whether they are rather to be regarded as bold and skilful experiments on the endurance and reparative power of the human frame – whether, in fact, they are surgical triumphs or operative audacities. There must, indeed, be a limit to the progress of operative surgery in this direction. Are we at present in a position to define it? There cannot always be new fields for conquest by the knife; there must be portions of the human frame that will ever remain sacred from its intrusion, at least, in the hands of the surgeon. May there not be some reason to fear lest the very perfection to which ovariotomy has been carried may lead to an over-sanguine expectation of the value and the safety of the abdominal section, and exploration when applied to the diagnosis or cure of diseases of other and very dissimilar organs, in which but little of ultimate advantage, and certainly much of immediate peril, may be expected from operative interference?Footnote 22

Was it concern at ‘operative audacity’, or at least the potential for an overly sanguine acceptance of mortality through experimentation, which encouraged Erichsen to resign his consulting post at the NHW? If he anticipated the growth of such procedures at the New then he was to be proved correct. From 1888, the hospital and its female surgeons made a break with the past, and, controversially, took the lead in their own operations, which provoked a storm of controversy within the New itself.

Divisions

Despite Garrett Anderson's desire for the female staff to perform surgical procedures themselves, they were still not always doing so by the mid-1880s. In March 1884, when a patient's death under anaesthetic was reported in the Paddington Times, it was evident that Garrett Anderson was only ‘present’ at the operation, while a member of the consulting staff was to perform the surgery.Footnote 23 The patient, 32-year-old spinster Sarah Brighton, had been suffering from bladder and kidney problems and had been in declining health for months. She entered the NHW after being encouraged to do so by her (male) general practitioner on 4 February. Within three weeks she was dead. A week before her death, an operation had been decided upon in order to prolong her life. Miss Brighton readily consented to the procedure, although her condition was deteriorating rapidly; both her pulse and heartbeat were faint, she was unable to eat much and her temperature had risen to 105. The operation was considered necessary; Miss Brighton's weakness both of pulse and heartbeat would have made the induction of anaesthesia a more risky business. However, the benefits were seen to outweigh the disadvantages of application and Miss Brighton was put under ‘quietly and comfortably’ by Mrs Marshall, assistant physician, while Meredith prepared to operate. The completeness of Mrs Marshall's professional credentials were reiterated by Garrett Anderson; the mixture of alcohol, chloroform and ether (A.C.E.) used to anaesthetise Miss Brighton was considered, as a textbook noted two decades later, still ‘nearly twice as safe as chloroform alone’.Footnote 24 Nothing unusual was noted, until Miss Brighton simply ceased to breathe. Resuscitation was continued for an hour and twenty minutes, but Sarah Brighton was dead. While her death was attributed to misadventure by the coroner, who noted that she had received every attention, Miss Brighton's brothers accused the hospital of overzealousness. One, James, wrote to the Paddington Times for ‘the benefit of young women who contemplate going to the Hospital for Women in Marylebone-road’, warning the vulnerable patient about what had happened to his sister.Footnote 25 As he claimed, she was neither taken into the hospital for an operation, nor had profited from any procedure carried out there. The first ‘extreme instrument operation’ caused Sarah Brighton ‘great agony’, while the ‘last and fatal’ surgery led to her death. James Brighton had requested that no operation be performed on his sister before he had consulted a medical man of his choice. Rebuffed in his attempt to do so by a recommendation to speak only with those connected to the hospital, Brighton felt he had been conspired against. The ‘most encouraging and hopeful assurances of the women of the hospital’ had effectively hoodwinked his weakened sister into consenting to surgery he was convinced she did not need. While the inquest into her death concluded that the hospital was not to blame for Sarah Brighton's death, such adverse publicity would not have encouraged potential patients to trust the judgement of the woman surgeon, even if it was not she who was carrying out the operation. Worse, James Brighton remarked, was the very female persuasiveness brought to bear upon a seriously ill member of the same sex. The woman surgeon could be deadly even by proxy. Such a taint of hasty recklessness would come back to haunt the hospital in the 1890s, as we shall see, when another accusation of poorly-administered anaesthesia, in addition to ongoing concerns about operative excess, forced the New on the defensive once more about its surgical practices.

If Garrett Anderson had not operated in this instance, there were other occasions when she was in charge of the procedure. While she had apparently operated alone successfully for the two ovariotomies in 1878, subsequent results were not so pleasing. When a patient died from an ovarian tumour and consequent peritonitis, the Annual Report for 1879 was keen to stress that no operation had been performed in this case.Footnote 26 The Managing Committee was evidently conscious of the ongoing sensitivity of the subject and wanted to protect the New from accusations of improper conduct. In 1880, though, it was noted that there had been an in-patient death from a suppurated ovarian cyst, where ovariotomy was placed in brackets after the cause of death. The patient died after the operation, but bracketing the procedure ensured that the cause of death was recorded as the suppurated cyst.Footnote 27 A similar case took place in 1881, whereby the patient had succumbed to bronchitis after an ovariotomy for an ovarian cyst. It was added that this patient was 69.Footnote 28 As the Minutes noted every year, it was Garrett Anderson herself who prepared the Annual Report, so a careful public presentation of controversial procedures was in the interest of the staff and, of course, the hospital, in the eyes of its subscribers and those who followed the careers of medical women.

While it is not clear precisely who was assisting whom in surgery, the impression given by the hospital was that the women were performing their own procedures at this point. However, cross-referencing the hospital records with statistics presented in print by members of the consulting staff offers a fascinating glimpse into how involved the supposed consultants to the New really were in day-to-day surgery. In May 1882, Garrett Anderson proposed that W.A. Meredith be appointed Consulting Surgeon to the hospital.Footnote 29 Meredith had assisted both Erichsen and Spencer Wells, and was clearly an impressive addition to the list of consultants.Footnote 30 In 1889, Meredith published ‘Remarks on some parts affecting the Mortality of Abdominal Section’, which was illustrated with ‘Tables of Cases’. Table I was a list of ‘One Hundred and Four Completed Ovariotomies’ and Table II listed 12 ‘Operations for the Removal of Diseased Uterine Appendages’. Of these cases, seven were from operations undertaken at the New between 1882 and 1887: five ovariotomies and two removals of appendages. Indeed, as the Annual Report for the hospital remarked, the increase in surgical cases was evident from 1882, when the very fabric of the NHW began to alter because of the focus on surgery. The average number of in-patients declined due to ‘the presence in the Hospital of a larger number of serious surgical cases, each one of which has frequently occupied an entire ward for several weeks’.Footnote 31 In 1882, there was one operation noted for an ovarian tumour, which tallied with Meredith's list concerning his procedure at the New this year.Footnote 32 Garrett Anderson was clearly not the surgeon taking the lead here. During 1882, indeed, there was only one death over the entire year, out of the 205 patients admitted into the NHW. The previous year had witnessed five deaths out of 221 patients.

With Garrett Anderson in Australia from January to autumn 1885, the two operations noted as ‘ovarian cyst’ in the Annual Report for this year were performed by Meredith.Footnote 33 Two years later, in 1887, the patient with a dermoid ovarian cyst was also Meredith's.Footnote 34 The majority of ovariotomies occurred in 1886, when there were three operations for ovarian cyst, with one death; Meredith's patient survived, according to his statistics.Footnote 35 It is therefore likely that the patient who died was operated upon by Garrett Anderson, whose success rate that year was 50 per cent. She had written enthusiastically to her husband, who was in America, about the ‘excellent’ recovery of her patient and the removal of a tumour, which had been ‘a very uncommon case’ and which had, consequently, been offered ‘to the Museum of the College of Surgeons as [Sir Spencer] Wells says they have only one like it’.Footnote 36 This was not the last time Garrett Anderson felt misplaced confidence about her patients’ futures after surgical intervention. It was this discrepancy between surgical ambition and operative success which led to resignations from the New in 1888; a year of staff losses which were instigated by Meredith himself, alarmed at what he had witnessed in the operating theatre.

Three departures from the NHW in 1888 not only revealed uncertainty over the question of female surgical aptitude, but also placed a question mark over what Elston has called ‘the nucleus of a professional and a friendship network that sustained pioneering generations’ in the earliest women's hospitals.Footnote 37 Meredith was the first to leave, but he was followed in swift succession by Louisa Atkins and Mary E. Dowson. Both women were renowned in different, but equally important, ways in the battle for female entry into the medical profession, as well as, more specifically, in the history of women in surgery. As we saw in the introduction, Louisa Atkins secured a controversial post as a house surgeon in 1872 at the Birmingham and Midland Hospital for Women, when she was pitted against, and beat, two men in the final stages. When Atkins left in 1874, the philanthropic physician Thomas Heslop, co-initiator of the hospital, stated feelingly that: ‘the accession of that lady to the number of practitioners of surgery would be welcomed, and upon leaving that hospital, she would leave behind her a reputation, which he trusted would serve her most essentially in her whole future life’.Footnote 38 Atkins had proved that women doctors could work alongside men, and gain their respect and trust, even in surgical cases. Mary Dowson's achievements were more recent, but equally vital in advancing the cause of medical women and, most importantly, that of female surgeons. Dowson had the ‘honour’, as the BMJ put it in the summer of 1886, of becoming ‘the first woman admitted as a surgeon on the roll of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland’, thus becoming the first qualified female surgeon.Footnote 39 She had been working officially as the pathologist and unofficially as a ‘chloroformist’ at the New since 1886, but had secured surgical qualifications when the RCSI took the unprecedented step in opening their doors to women in 1885. To lose both women, known, within the medical profession and widely amongst the newspaper and periodical-reading lay public, as surgical pioneers, was a double blow for the New.

The departures began at the start of 1888, but the impact of Meredith's resignation was such that the copy of the Annual Report for the previous year, held at the London Metropolitan Archives, shows his name already crossed out, and that of his successor, Knowsley Thornton, another distinguished abdominal surgeon of the Samaritan Free Hospital, added firmly in ink.Footnote 40 The Managing Committee Minutes of 1 February 1888 record that Meredith had felt ‘obliged’ to resign his post as consulting surgeon, and that Thornton had already been engaged in his place. Evidently, Meredith's discomfort in his position had been apparent for some time, if the hospital had already managed to secure another surgeon to replace him. The Annual Report for 1887, published in March 1888, noted briefly Meredith's resignation and offered a statement about the ‘valuable assistance’ he had given ‘to the surgical work of the Hospital’ over a five-year period.Footnote 41 Meredith's ‘helping out’ here rather than actually undertaking many major operations reveals how keen the hospital was to give the impression that the female staff were taking the lead in clinical work. A protest lodged by Louisa Atkins at the same meeting in which Meredith's resignation was tendered offered a fascinating glimpse into the inner workings of the hospital hierarchy. Garrett Anderson's keenness to uphold the New's purpose as an institution where female medical talents were nurtured was becoming more and more vehement. Proposing that Mary Scharlieb become her clinical assistant at operations, Garrett Anderson encountered a frustrating negative from Atkins, who was not convinced by Scharlieb's surgical competence, and stated unequivocally that she would herself resign if the Committee did not allow her to send serious operation cases to other hospitals if Scharlieb and Garrett Anderson were to work as a surgical team. This dissension from the New's remit as a hospital which supported the clinical ambitions of women doctors presented a shocking ultimatum to the Committee.

It was, however, clearly a step too far, as the next meeting began with Atkins’ objections, quoted verbatim in the minutes:

Feb 22/88

To the chairman

Management Committee

Dear Sir,

Referring to the conversation which took place at the last meeting of the Management Committee relative to the present system of operating for abdominal diseases at this Hospital I shall feel much obliged if you will lay my views before the Committee for their consideration.

Hitherto skilled assistance has been applied by Mr Meredith at every serious operation. This assistance is now lacking and I firmly believe that without such assistance the performance of abdominal sections at this Hospital will be injurious to the patients, to the cause of medical women and to the Hospital itself.

Feeling this I could not justify it to my conscience to allow any patient of mine to be operated under the present system. I therefore ask the Committee to consider whether they can allow me either to send my patients to be operated at the Samaritan or to ask Mr Thornton whether he will consent to operate them at the NHW, or, should they consider both these propositions impracticable, whether they can make any other arrangement which will ensure the best interests of the patients.

Otherwise nothing remains for me but to resign my post though I shall do so with great regret for the loss of the post itself and a very real sorrow for the necessary severance from a colleague with whom I have worked amicably for so many years. I am dear Sir

Yours faithfully,

Louisa Atkins.Footnote 42

In this letter, Atkins confirmed the extent to which Meredith had been present at ‘every serious operation’, implying that Garrett Anderson lacked confidence in operating alone. Such an assessment of the potential disaster awaiting patients at the hands of women surgeons was a stark warning about the paucity of female surgical experience and training.

The Managing Committee responded in an intriguing way. Rather than disregard Atkins’ point, they agreed that, although it was not advisable for the reputation of woman doctors and the status of the New itself to send surgical patients elsewhere, they did not want to lose Atkins and would, therefore, ask a reputable witness to comment on Garrett Anderson's surgical technique. It is noticeable that Atkins’ original focus on Scharlieb's capabilities had now disappeared and it was Garrett Anderson who was wholly under scrutiny, suggesting that this was where Atkins’ original concern really lay. It is also telling that the idea of submitting Garrett Anderson to independent verification came from Garrett Anderson herself, perhaps both to protect her own surgical standing, as well as, given her doubts about operating, for self-assurance. The receipt of Atkins’ complaint further compelled Garrett Anderson to report on every operation to the Committee, as well as, from this point, the recording of every surgical procedure in the Annual Report for wider public perusal. Members of the hospital staff and management evidently felt some sensitivity about surgical competence to clarify the facts and figures at the same time as undergoing internal divisions over precisely this issue.

Louisa Atkins was, however, not mollified by such an offer. This controversy had exposed a rift which only widened over the next couple of months. The independent witness, George Granville Bantock, appointed President of the British Gynaecological Society in 1887, refused to undertake an examination of Garrett Anderson's surgery, as he felt that all operations in the hospital should be performed by the all-female staff. Bantock worked with Thornton and Spencer Wells at the Samaritan Hospital in London and was a keen ovariotomist.Footnote 43 The support of such an important figure would have been incalculable, but so, because of his defence of the female surgeon, was his refusal. Garrett Anderson continued to operate. By late March 1888, Atkins issued an ultimatum. Either she be allowed to send her patients to a surgeon outside the hospital, as was the norm elsewhere, or she would resign immediately. Atkins’ resignation at the beginning of April came after she had, presumably by suggestion, witnessed another operation by Garrett Anderson, which, however,

did not in the least modify my opinion that she is not competent to undertake such operations singlehanded. I deeply regret the course taken by the Committee as it will assuredly confirm the growing opinions that in the minds of the Staff personal or collective advantage takes precedence over the sense of responsibility for the lives of the patients.

This being my own opinion I cannot any longer acquiesce in the existing arrangements and must ask the Committee to appoint my successor at the earliest date possible.

My medical connection with the Hospital being severed you must allow me as a subscriber to express my great surprise that a course of action taken by any members of the Staff which necessitates the resignation from conscientious motives of three members of the Staff should not have been more thoroughly investigated by the Committee; and further to state my opinion which will I believe be shared by all disinterested outsiders that the neglect of the Committee on this point is injurious to the interests of the patients, the Subscribers and the Hospital.Footnote 44

Rather than act professionally in this instance, claimed Atkins, the hospital was compelled to protect and bolster Garrett Anderson in her public image. This meant that the triple resignation, due entirely to ‘conscientious motives’ and concern for the patients, was obscured from the outside world. To compound this ‘neglect’, there was to be no enquiry into the reasons for their departure. The Committee was dealt another blow in this meeting, as Mary Dowson also tendered her resignation for precisely the same reason as Atkins. Dowson's letter, less fulsome than Atkins’, reflected upon her disagreement with the ‘policy now pursued with regard to operations [which] precludes my working in harmony with the Medical Staff’.Footnote 45 By supporting Garrett Anderson, as the most senior woman doctor in the hospital and the most renowned female medical pioneer in Britain, the Committee had lost three valuable members of staff in as many months. The cause of medical women and their right to perform surgery had been supported, but only by disregarding the mistakes, which Atkins and Dowson had felt sufficiently serious to merit complaint.

In June 1888, Meredith wrote to clarify his reasons for departure. He ‘found that the record of Mrs Anderson's operations at which he had been present shewed too high a percentage of failures’, but that he ‘should always retain a kindly feeling towards the Hospital and its staff’.Footnote 46 Subscribers, as predicted by Atkins, also expressed concern at the evident problems within the ‘internal workings’ of the hospital, and two wrote for clarification. They were pacified with the knowledge that a difference of opinion had resulted and that staff had resigned rather than been dismissed from their posts.Footnote 47 The Hospital Letter Book contains the response to Miss A.R.C. Wainwright, which was dated 24 April 1888. Miss Bagster's tone was defensive, but honest:

Dear Madam,

We are having papers printed to send to the subscribers to inform them of the changes in the Medical Staff.

With regard to Miss Atkins's resignation, her own explanation was that she could not consent that her own patients should be operated on in severe cases by one of the Women Physicians.

It was with great reluctance that the Committee accepted her resignation.Footnote 48

However, Miss Wainwright was clearly not yet satisfied with the explanation and the following letter in the book asked her to attend a meeting with the Committee.Footnote 49 The fact that this letter was dated three months after the last implied that a brief correspondence was insufficient. A more personal explanation from the Committee themselves must have resolved the issue, as there were no more letters from Miss Wainwright.

In public, the summer of 1888 saw the launch of fundraising for new premises, whereby, in opposition to the surgical controversies of recent months, the phrases ‘low death-rate’ and ‘skill, care and attention’ formed a consistent refrain whenever the hospital was mentioned.Footnote 50 In June 1888, Garrett Anderson's surgical skills were witnessed and approved by the curious choice of Francis Imlach, a surgeon at the Women's Hospital in Liverpool, and a man who was no stranger to libellous remarks about his own capabilities. Only two years previously a scandal had threatened to end his career, when Imlach had been accused of performing unnecessary ovariotomies, and ‘unsexing’ his patients. Although he was acquitted of any wrongdoing, both in an internal enquiry and after a complaint from a patient's husband was rejected in court, Imlach's reputation, as well as the cause of radical surgical procedures for the diseases of women, received a setback. Garrett Anderson had been called upon as an expert for the report investigating Imlach's cases, and had concluded ‘that the work done during the year is very creditable to the skill and courage of the medical staff of the hospital’.Footnote 51 Imlach repaid her loyalty when Garrett Anderson's skills were questioned: ‘“Have just witnessed as difficult an abdominal section as any surgeon could have to perform; and think that in technical skill and promptness I have never seen anything much more perfect”. Francis Imlach’.Footnote 52 The ‘four or five’ procedures originally suggested by Garrett Anderson herself in February, in order to appease Louisa Atkins, had been reduced to just one unidentified abdominal section. Additionally, her competence had been assessed by someone whose own had only very recently been scrutinised.

With the backing of the hospital's Managing Committee and independent verification of her abilities, Garrett Anderson began to perform more complex and risky procedures ‘entirely without outside help’.Footnote 53 It was also noticeable that she reported on her operations at meetings of the Managing Committee, either for self- or institutional reassurance. Even while the disagreements with Atkins were at their height, Garrett Anderson, in a specific section of the meetings now devoted to her surgical report, made clear her performance of unspecified ‘difficult abdominal operation[s]’, where the patient was ‘so far doing well’.Footnote 54 Yet this was also in line, as Sally Wilde argues, with the trend in the 1890s, as procedures developed, for major, new surgery to be performed, which had never been attempted by the surgeon before.Footnote 55 Interestingly, soon after the triple staff resignations, oophorecetomies were first conducted in 1888. That year, Garrett Anderson was vindicated, as there was only one operation death out of 54 cases, and now they were listed separately for the first time, this success was even more evident. The following year there was only one death, again from an ovariotomy, this time from a total of 81 cases.Footnote 56 Over the next three years, the hospital saw a move away from operations concentrating on the diseases of women and entered new surgical territory, with the introduction of ophthalmic surgery, as well as the performance of a splenectomy in 1890, and nephrectomies from 1891. The latter operation had first been performed successfully in Britain only six years before Garrett Anderson's attempt, by a member of New's consulting staff, Knowsley Thornton.Footnote 57 Surgery on the spleen was very rarely attempted, even in the experimental 1890s by the most prominent risk-takers. As Skene Keith noted in 1894: ‘[t]he general mortality has been so great that an operation which may have to end in the removal of the spleen is one which requires very grave consideration’.Footnote 58 Five years later, the American surgeon Charles T. Parkes concluded that splenectomy was ‘attended with such overwhelming mortality, that its performance can scarcely be justified’.Footnote 59 Despite Thornton's experience, he had sworn after two further failures, where both patients bled to death, and the death four years later of his only successful case, never to perform this procedure again.Footnote 60 Thus it appears that Garrett Anderson took the lead here; this was corroborated in a letter to her sister Millicent Garrett Fawcett, which noted the rarity of the procedure:

I had a very big operation at the New yesterday and so far all promises very well with the patient […] [I]f mine recovers it will be quoted for a long time. – I fancy too that [mine crossed out] the tumour in my case was larger than any yet. It was a much overgrown spleen. I tell you this for the sake of the cause.Footnote 61

Unfortunately, the patient died from septicaemia, so Garrett Anderson had achieved neither plaudits for the hospital nor for the female surgeon. Risk had been implemented at the New for ‘the sake of the cause’; precisely what had been feared by Louisa Atkins two years previously.

Between 1891 and 1892, six nephrectomies resulted in a 66.7 per cent mortality rate; in 1888, Lawson Tait had recorded, from 12 cases, only two patient deaths.Footnote 62 There was an inevitable element of risk in performing new procedures such as this, but, with the surgical profession still acquiring confidence in itself, surgery at the New had to be carried out with an eye to innovation and progression if women were to operate fully.Footnote 63 The increase in procedures and specifically in serious abdominal operations was noted by the House Committee at the beginning of 1892. A ‘great tax’ was being placed on the nursing staff, which had been necessarily supplemented by outside help.Footnote 64 The hospital was simply not prepared for an upsurge in operations. By May of that year, however, a dedicated ‘Ovarian Ward’ had been created, later to be renamed the Louisa Isaac Ward, creating space for the recovery of serious operative cases, as well as indicating the dedication to still-controversial procedures.Footnote 65 When Garrett Anderson decided to hand over her post to Scharlieb in autumn 1892, 44 major operations and abdominal sections had been performed, with a mortality rate of 13.6 per cent, more than double the previous year, when there were 84 cases (minus eye operations), but with just under 6 per cent mortality. By the time she passed on her post, Garrett Anderson had been assisting others and performing surgery herself for 20 years. She had not been specially trained in the discipline, but then, as Scharlieb put it, early women medical pioneers were ‘never able to be what is called pure physicians or pure surgeons. We had of necessity in those early days to be willing to give advice to women as to their health, whether from the medical, surgical or obstetric point of view’.Footnote 66 Female medical staff at the New had proved that women could perform complex and difficult procedures. The woman surgeon could exist, and operate no differently to her male comrades, who had received more specialist clinical and surgical training. However, while surgery revealed precisely what women could do, it also highlighted their limitations. The early woman surgeon was forced to contend with her own difficulties, but she was also faced with opposition from her colleagues. If, as Garrett Anderson claimed, one could only become skilful though experience – ‘no one can operate well who is not operating constantly’ – curtailing and disrupting practice was a regular feature of the first 20 years of the NHW.Footnote 67 Although the New was founded to support medical careers, surgery was one area in which male and female members of staff could unite against the progression of the woman doctor.

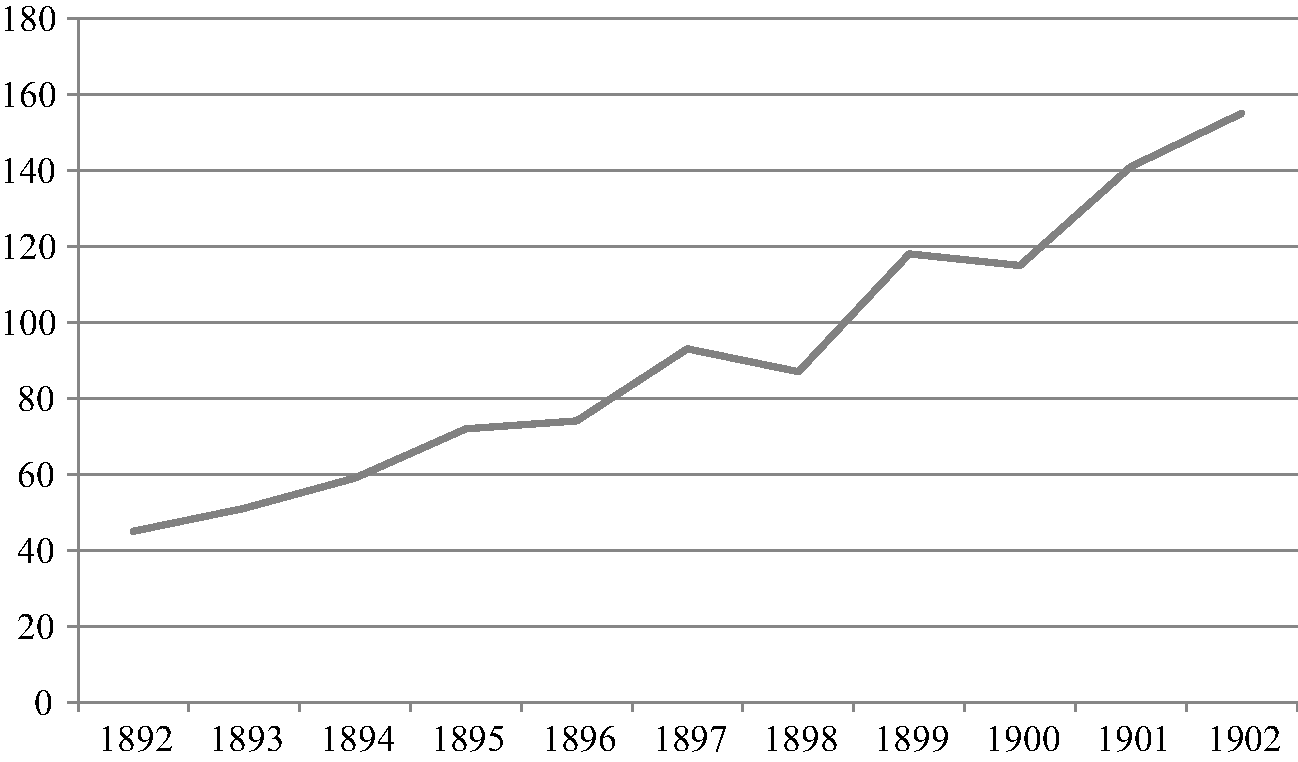

The 1890s

Controversy was not to leave the woman surgeon in the 1890s, but scandal was tempered with success. This decade saw both ongoing controversy surrounding Garrett Anderson's surgical principles, even when she was not actually practising at the hospital, and, with a new team operating, a formalisation of the NHW's commitment to the cause of female surgeons. The number of operations increased, as indicated in Figure 1.1, yet they did so at a steady rate and ranged more widely than the predominantly gynaecological procedures carried out during Garrett Anderson's reign. This is not to state that the decade which witnessed Mary Scharlieb's management of the New's surgical side saw the primary focus of the institution change nor that the ‘cause’, as Garrett Anderson would have put it, was in any way discouraged by the operations performed. Rather, Scharlieb's decade-long regime was characterised by the recognition that the individual operator was part of a team of professionals, who acted together for the good of the patient. The period between 1892 and 1902 was one of consolidation at the NHW, where female surgeons were encouraged to carry out a wider range of surgery to enhance their experience. It was also one where, in spite of continuing attacks upon their abilities, women surgeons gained confidence by operating quietly and allowing the statistics to speak for themselves.

Figure 1.1 Major Operations Carried Out: NHW, 1892–1902.Footnote 68

Within a month of Garrett Anderson's resignation, the Managing Committee received the report of the Medical and Sub-Committees which called for the following resolutions:

1) That members of the Medical Staff should retire at the age of 60.

2) That Mrs Scharlieb and Miss Cock should be appointed to the Inpatient Surgeons.

3) That Miss Webb and Mrs Boyd be appointed to the Outpatient Surgeons for five years.

[…] 8) Abdominal operations. That Mrs Scharlieb be authorised to perform these operations and Mrs Boyd assist. That no member of the staff be authorised to perform abdominal operations until she has acted as principal assistant in this hospital with at least 12 cases; and that any number of staff may claim the right to assist with their own cases.Footnote 69

The resolutions were put to the vote and passed. What is interesting about the first point is that Garrett Anderson had retired from the New at the age of 56. While the mistakes perceived in the 1880s were never put down to the age of the surgeon, it was clearly a concern for the future. Additionally, of course, retirement when posts for women were still so scarce was fundamental to fulfilling the hospital's mission statement of assisting female members of the medical profession to gain institutional experience.Footnote 70 Similarly, points 2 and 3 rewarded the experience of Scharlieb, Cock, Webb and Boyd, while simultaneously restricting the outpatient roles of the latter two to five years only. As hospital clinical work was always gained first at outpatients, this allowed both the chance to progress to in-patient roles, but also to permit others, in turn, to take their place seeing temporary cases. The most telling point, given the concerns about surgical ineptitude, was number 8, which demanded at least a dozen assistant roles before abdominal operations could be carried out. If the 1890s was characterised by the growth in experimental procedures, the NHW was urging caution, at least as far as operating-theatre personnel were concerned, and insisting upon some practical experience for its surgeons. This point also gave members of staff more control over their own cases. That Garrett Anderson had taken the lead in surgery at the hospital was evident when, upon her departure in November 1892, the New was also deprived of its surgical instruments. Some more would be needed, remarked the Secretary, as ‘Mrs Anderson would be no longer lending those that she had been in the habit of bringing for major operations’.Footnote 71 Without Garrett Anderson exercising manual control,Footnote 72 although there was a need for new instruments, there was evidently more freedom to follow patients from consultation to operation, as well as participating in their surgical care. The Managing Committee, in approving the demands made by their medical counterpart, had evidently learnt from the débâcle of the previous decade that rifts could not be healed by placing trust only in one person.

With this change in outlook after Garrett Anderson's departure, it is fruitful to consider how the New dealt with very public accusations of surgical misconduct. Two controversies hit the institution during the 1890s, but they were handled very differently to those of the 1880s. Both stemmed from criticism about the ways in which surgery was performed at the New. The first came from a surprising source: Elizabeth Blackwell, the 73-year-old grande dame of medical women. Her opinion was sought in connection with ongoing rumblings of discontent about the ways in which hospital patients were abused and experimented upon by bloodthirsty, ambitious surgeons. In May 1894, the Daily Chronicle newspaper ran a campaign to expose what it labelled ‘human vivisection’, a practice, it noted, which was occurring in hospitals throughout Britain. The outcry was part of a late-Victorian obsession with the increasing power of medicine and the medical profession over defenceless individuals, who were stripped of their liberty by the probing instruments of scientific experimentation.Footnote 73 Vaccinators and vivisectors had borne the brunt of public loathing for over a decade; now it was the turn of the surgeon to be subjected to charges of brutality. ‘Houses of charity’, shrieked the Chronicle, were being turned, by younger, ambitious members of the surgical profession, into ‘butchers shops’ [sic], whereby innocent, and it was alleged, healthy, individuals were persuaded to undergo unnecessary and dangerous operations. Not for their own benefit, of course, but all for the desire to ‘destroy human lives in the interests of science’. According to the Chronicle's exposé, the grasping surgeon experimented upon patients solely to keep up with the latest ‘surgical fads’, while unsuspecting patients simply agreed to the operator's demands.

The paper lambasted the Dickensian-sounding youths who made up future practitioners:

The new school consists of […] enthusiasts who have only just passed from the stage at which young men go forth from the hospitals on football or boat-race nights to parade the West End in gangs, knock foot passengers off the pavement, and then, in the interests of what they call sport, destroy the glasses of some more or less innocent proprietor of a West End drinking-bar; and, having returned to their Bayswater or Bloomsbury lodging in the early morning and tried to sleep off the effects of bad whisky and worse cigars, go forth to gloat over men older than themselves destroying human lives in the interests of science.Footnote 74

Louche, irresponsible, idle and careless, these were the people in whose hands lay innocent lives; untrustworthy, clumsy and dangerous youths. The claim that daring operative procedures represented progression was dismissed scornfully, as contemporary surgery was branded uncivilised and barbaric. In a celebratory edition, published for the Diamond Jubilee of Victoria's accession to the throne, the BMJ begged to differ. Labelling the era a ‘Renaissance’ as far as the advancement of surgery was concerned, the periodical concluded that ‘Heaven has given us a new race of men’. It was indeed a ‘Golden Age’:

The student sixty years ago would see an occasional operation for strangulated hernia, perhaps an ovariotomy; there he would stop. The radical cure of hernia, known to Paré, had fallen into disuse; the surgery of the liver, the gall bladder, and the kidney was unknown. Perforation of the stomach, or the bowels, or the appendix, was left to itself; cases of acute obstruction shared the same fate; so did ruptures of the abdominal viscera from external violence. The general work of abdominal surgery was hardly so much attempted, save perhaps once or twice in a surgeon's lifetime. Of such success as we now obtain there was not a trace.Footnote 75

Where the Chronicle saw destruction and frailty, the BMJ envisaged exploration and progress: the preservation of health rather than the wilful encouragement of illness. For the latter, the Victorian period had witnessed unprecedented ‘success’ through the development of procedures previously considered impossible and the conquering of disease in organs and parts of the body assumed inaccessible. Risk was essential to progress.

It was surgical exploration of and operation upon the abdomen, however, which still caused the greatest outcry at the end of the nineteenth century. The Chronicle article had been prompted by a report issued by the Medical Officer of Health for Chelsea, Dr Louis Parkes, who had recently expressed concern about the disproportionate number of fatal operations at the Chelsea Hospital for Women. Hospitals specialising in the diseases of women were, time and again, the focus of public distrust. Some of the most virulent controversy surrounded abdominal surgery on women; the surgeon demonised in popular culture as a human vivisector, experimenting dangerously and without a care upon the defenceless female, robbed of her organs of generation. Ovariotomy was considered both ‘the starting point in the modern advance of abdominal surgery’, as Spencer Wells put it, and a practice considered initially as ‘little short of murder’, as Ornella Moscucci has noted.Footnote 76 Notorious cases such as that of Francis Imlach and the more recent accusations of Alice Beatty against her surgeon Charles Cullingworth for removing both her ovaries without consent helped to keep such controversial surgical procedures in the public mind.Footnote 77 With such a history, abdominal surgery, particularly that upon women, was both momentous progress and barbaric regression. The subject was particularly emotive when the popularity of operations to ‘unsex’ women was contemporaneous with the increasing social anxiety over the high rate of infant mortality.Footnote 78

For some, the risk was unacceptable. The Daily Chronicle sought the viewpoint of the first woman to qualify professionally as a doctor by being placed on the Medical Register: the British-born, but American-raised, Elizabeth Blackwell. Despite Blackwell's age, her iconic status meant that the Chronicle had secured an impressive scoop. Blackwell had a great deal to say about the alarming, as she saw it, trajectory of the woman who performed daring surgical procedures. She feared that surgery, with its glamorous and daring status, had replaced medicine as a ‘cure-all’. The modern-day approach, she felt, was too hurried and too impatient. Blackwell's concerns were not only for helpless female patients, however. She used the Chronicle reporter to voice her distrust of those women only too keen to perform ‘reckless operations’ which ‘maim[ed]’ their own sex for life. Prompted by what sounded like an attack upon her fellow medical women, the reporter asked: ‘Do you consider that women practitioners are less liable to this “operative madness” than men?’ Blackwell's response was intriguing:

I have no hesitation in saying that at present my own sex is suffering from the epidemic, but it is imparted to them by their surroundings. You see it is very contagious. They learn from men, and live in the atmosphere of surgery. They are over-anxious to do as men do, and so their reverence of creation and their sympathy for the poor and suffering is in abeyance. A woman – and a very clever one – boasted recently that she had just completed her fiftieth operation of a particular and very dangerous kind – a kind such as I think it must have been difficult to find within her reach, fifty cases in which it was necessitated. She had probably been taught that the operation was frequently necessary, and she is no more reckless than those who taught her; but her sense of humanity was, perhaps, for a while in abeyance. I am, however, persuaded that this will pass away so far as women are concerned; the danger is an almost inevitable accompaniment of the early stages of a movement in the ultimate success of which I have the greatest belief – the educating of women so that they may alleviate the physical sufferings of their own sex, not only as nurses, but as physicians and surgeons. I do not believe that the study and practice of surgery necessarily tend to unsex a woman. It is a noble work, this curing of disease, and must be nobly done, whether by men or women.Footnote 79

Blackwell had intended to devote her life to surgery, but had been infected with purulent ophthalmia by a young patient at La Maternité in Paris, which had left her blind in one eye and incapable of intricate surgical procedures. She was, therefore, unable to become, as she had hoped, ‘the first lady surgeon in the world’.Footnote 80 So, while Blackwell did not believe that the existence of the woman surgeon was wrong per se, the aping of the infectious masculine swagger of surgical success could only detract from the true ‘curing of disease’. It was this discrepancy between the risks involved in opening up a patient and the ultimate restoration of health which was so distressing for this elderly pioneer.

Blackwell drew pointed attention in this interview to a very clever female boaster, who could only be Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. As we have seen in the first part of this chapter, Garrett Anderson was notoriously keen to promote the surgical work done at the NHW for the ‘sake of the cause’. Blackwell criticised Garrett Anderson for three things. Firstly, performing unnecessary procedures and therefore ignoring the real cause of illness in order to risk lives for reputation's sake; secondly, for trying to compete with and even outdo male surgeons; and, finally, because a combination of both these reasons meant she was losing her humanity in the process. Indeed, even though Blackwell was still acting – in name, if not literally – as a consultant physician to the New, the Managing Committee of the hospital chose to maintain a dignified silence over these pointed accusations. In the first meeting of the Committee after the article was published, on 31 May 1894, the notes record that the Chairman, Mr Gaselee, will write to Garrett Anderson – evidently the target of the accusations – to prevent her from responding to Blackwell's article or from being interviewed in the Daily Chronicle.Footnote 81 The fact that this was passed unanimously revealed how troubled they were by Garrett Anderson's potential to make matters worse, by engaging in public combat with her predecessor. After a decade of internal divisions over surgical procedures, drawing attention to the painful schisms which had existed in the hospital would not encourage its patients to undergo some of the operations at which Blackwell was hinting. Nor would accusations of recklessness, as far as patients were concerned, do anything for the reputation of the female surgeon. Blackwell was clearly willing, without directly identifying perpetrators, to critique the hospital for which she still acted as consultant. That institution, however, was not willing to involve itself in an unseemly debate which could only sorely inflame public sensibilities and hint that all was not well among ‘lady doctors’.

Three years later, in October 1897, another accusation of improper conduct was directed at the NHW. Unlike the Chronicle attack, however, this one named the hospital outright, even pinpointing its location. The only saving grace in this latest scandal was that it took place in an American medical publication and much effort was expended in order to keep it on the other side of the Atlantic. A. Earnest Gallant responded to a recent editorial on ‘Anaesthesia as a Speciality’ in the New York-based Medical Record with a corresponding glance at British anaesthetists. To do this, he posed a series of questions about the development of the specialty to his friend George Bell Todd, Professor of Zoology at Anderson College Medical School and well-known Scottish practitioner. In an apparently innocuous article, Bell Todd made a curiously libellous comment. Apropos of nothing, he stated: ‘I may here remark that female medical practitioners in this country are peculiarly unfitted to give anaesthetics. That such is the case I know from experience and it is well illustrated at the Women's Hospital, Euston Road, London, which is remarkable for the failures in administering chloroform correctly.’Footnote 82 Here Bell Todd unmistakably identified the New, which had, of course, moved to the Euston Road in 1890. Neither did he mention any other institution by name nor critique any other administrator of anaesthetics, so the NHW's prominence, or, it might be said, failure, was more pronounced. Furthermore, Bell Todd did not support his comment with any other evidence. The surgeon was not blamed for any mistakes while a patient was on the operating table, but responsibility was placed squarely in the hands of the anaesthetist. Such focused censure for errors made during surgery may, however, provide an explanation as to why Bell Todd directed such bile at the NHW.

As Ian Burney has remarked, the 1890s witnessed developments in the professionalization of the anaesthetist, but also a corresponding increase in anaesthetic deaths.Footnote 83 This, in turn, fuelled the wider publicity during the same period surrounding the danger and unreliability of anaesthesia,Footnote 84 and, ultimately, the practise of surgery in Britain. In the early 1890s the anaesthetist to the hospital was Mrs Keith, who had been in her post since 1889 and was noted as having given anaesthetics 115 times during 1893.Footnote 85 In the autumn of 1893, the House Committee had also called for a book specifically to note the administration of anaesthesia, evidently aware that a record was crucial.Footnote 86 Deaths from the process were few, however, in spite of Bell Todd's accusations. Of eight surgical deaths in 1893, only one resulted while under anaesthesia.Footnote 87 This death was publicised and the report in the BMJ might have given Bell Todd cause for concern. ‘Death Under Chloroform’ was a regular feature in the periodical, but not one which frequently detailed cases at the New. The dead patient had suffered from goitre and some dyspnoea, but displayed no evidence of cardiac or respiratory disease. There were no problems to begin with, but after ten minutes, the chloroform was removed due to rapid, deep breathing. Breathing then ceased and although artificial respiration was carried out for three-quarters of an hour, the patient showed no signs of recovery.Footnote 88 The Hospital Letters Book provides further information about what happened to 43-year-old Mrs Jane Valentine, including a heart-breaking response to her husband, who, whether through superstition or distrust of anaesthesia, had clearly sought to prevent the operation to which his wife had consented. As the secretary writes:

Dear Sir,

It is with the greatest regret I have to tell you that the operation of your wife was begun before I received your letter. She had expressed her wish to have it done and gave her consent.

I feel deeply sorry that we did not hear from you sooner for your wife died under the chloroform. I can only add my sorrow for you in this great trouble.Footnote 89

Notification of the death was also made to the coroner through a letter from the Resident Medical Officer, Annie Anderson, who stated that ‘a patient died from the effects of chloroform administered for an operation for removal of part of the thyroid gland’. She continued that death was in no way due to the operation, which had barely begun, and that artificial respiration and circulation were carried on for some time after apparent death.Footnote 90 The inquest on Mrs Valentine was further noted in the Minutes of the Managing Committee on 13 July.Footnote 91 Neither the letter to Mr Valentine, the report to the coroner, nor the acknowledgment of the death in the BMJ mentioned the sex of anaesthetist or surgeon; the assumption, naturally, was that both were female.

In fact, while we can assume that the anaesthetist was Mrs Keith, the operator was in fact James Berry of the Royal Free Hospital, consulting surgeon to the New since 1891, and a specialist in the removal of goitres, who had clearly been called in especially for this difficult case.Footnote 92 Berry's leading role in this operation revealed inadvertently that the New were still seeking outside help for some procedures. Previously, a goitre sufferer in 1889 had been sent to the RFH, presumably to Berry, two cases in 1891 had been relieved, but not operated upon, while not one goitre patient for the rest of Scharlieb's regime underwent surgery at the hospital, even though there were six cases in 1902.Footnote 93 There were clearly some instances when even Garrett Anderson had acknowledged her lack of experience for the benefit of the patient, and Scharlieb evidently followed suit. The onlookers in Mrs Valentine's procedure were Stanley Boyd, Surgeon to the Charing Cross Hospital and consulting surgeon to the New, as well as other NHW staff members. When he wrote about this case in 1900, Berry remarked on a number of points relevant to the decision to operate on ‘Jane V.’. Mrs Valentine's goitre was especially dangerous, as it was both parenchymatous, and causing her dyspnoea, which required urgent operative treatment before it killed her. Anaesthesia was, therefore, vital, as the goitre required extirpating rather than a less serious enucleation. However, the death of Jane Valentine caused Berry to rethink his policy as to how a patient suffering from dyspnoea should be treated. He had, before this case, considered a general anaesthetic indispensable, regardless of the patient's condition, but in later procedures Berry adopted morphine, cocaine or encaine. Though only suffering three deaths from the 72 goitre patients upon whom he had performed extirpation, Berry justified his actions even in these fatal outcomes, because of the severity of dyspnoea. He concluded: ‘I know of no class of patients so grateful to the surgeon as those from whom a suffocating goitre has been removed’.Footnote 94 Although neither this, nor Berry's change in procedure, was any consolation for the Valentine family, the necessity of the goitre's removal overrode any concerns about the application of anaesthetics.

As the only publicised case of death under anaesthesia at the hospital in the early 1890s, it must have been what prompted Bell Todd's barbed comment. While Bell Todd blamed the anaesthetist in every failed procedure, Berry would surely have advised the member of his operating team dispensing the anaesthetic, especially if specialist care was required. By making the anaesthetist responsible, Bell Todd shifted the fatal outcome onto the shoulders of the dispenser rather than the adviser. Either way, he deemed the anaesthetist incorrect in her application and, therefore, professionally incompetent. If anaesthetic could not be dispensed accurately, neither could operations be carried out successfully: failure characterised the NHW. Although Bell Todd's words were published in late 1897, it was not until February 1898 that the Managing Committee of the hospital became aware of the slanderous accusations levelled at their surgical staff. They wrote immediately to ascertain whether the remarks could be ‘rightly attributed’ to Bell Todd and upon ‘what facts [he] base[d] the statement’.Footnote 95 Although Bell Todd responded reasonably quickly to this letter, he did not answer the second question about his sources for the claim.Footnote 96 There were no further records of correspondence in the Hospital Secretary's Letters Book, but the minutes of the Managing Committee offered more insight into how seriously the New took this unfounded report. The necessity of ‘plac[ing] the matter in the hands of a lawyer’ was mentioned at the meeting on 3 February 1898, when the story was first brought to the Committee's attention by the anaesthetist. Bell Todd clearly defended his stance, because on 10 March, legal advice had been sought and Bell Todd was communicated with again, without response this time. The minute concluded with a decision to send a solicitor's letter to state that unless an apology was sent to the hospital the correspondence would be sent to the BMJ.Footnote 97 Bell Todd evidently backed down at this point, although it was not until the summer that a solution was sought. A letter was drafted by Greenwell, the New's solicitor, and it was requested that Bell Todd publish it in the original American periodical, as well as the Lancet and the BMJ. A month later, however, Bell Todd had evidently demanded alterations, which were not accepted. It had also been decided, upon Greenwell's advice, not to submit the apology to the British medical journals.Footnote 98 In September 1898, nearly a year after the initial accusations of misconduct had appeared, George Bell Todd's response was published in America.

It is worth quoting the dictated letter in full.

To the Editor of the Medical Record.

Sir: My attention has been drawn to an article which appeared in your issue of November 13th last, under the title of ‘Anaesthesia and its Administration in Great Britain and Ireland’, by Prof. George Bell Todd, of Glasgow, and in which I am made to say that the Women's Hospital, Euston Road, London, ‘is remarkable for the failures in administering chloroform correctly’.

The article in question was a private communication from myself to a friend, and published without my knowledge or consent.

With reference to the extract above quoted I would remark that the information has been furnished to me by the authorities of the said hospital, from which it appears that between January 1, 1894, and December 31, 1897, anaesthetics were administered thirteen hundred times at the hospital, that there were during that period two deaths on the operating-table. Inquests were held in both cases, and in one instance only was a verdict of ‘death from chloroform’ returned. This shows that the above-quoted statement is unfounded and incorrect, and I regret that the sense should have appeared in the article referred to.

George Bell Todd, MB.

Glasgow, August 25, 1898.Footnote 99

The NHW's success here in ensuring Bell Todd retracted his statement was threefold. Firstly, Bell Todd's public acknowledgement that his comments were both incorrect and without foundation exonerated the hospital from any concrete blame in administering anaesthetics; secondly, that they were made privately revoked any sense of professional objectivity about the state of anaesthetic practice in Britain; and, finally, but most importantly for the New, in retracting his harsh judgement, he had been made to print the, in fact, impressive statistics achieved by the surgical team. From initially claiming that women were remarkable for their failures in administering chloroform correctly, Bell Todd was compelled to flaunt their outstanding achievement of a 0.15 per cent death rate on the operating table itself. This was a triumph both for the anaesthetist and, correspondingly, the skill of the woman surgeon and her all-female team. The hospital achieved a further accomplishment through its limited publicity of the case, confining Bell Todd's apology to the original source of the article. Publication in the British press may have led to unwarranted pressure of attention, as well as charges of bragging, something which the New were evidently keen to avoid since Garrett Anderson's departure and Blackwell's warnings in the Daily Chronicle. While the New won a moral victory here, this was not the last time Bell Todd would find himself forced publicly to reverse his opinions. In 1912, he was struck off for procuring abortions, a charge for which he had also been tried and acquitted the previous year, and sentenced to a lengthy seven-years’ penal servitude.Footnote 100

While the NHW had treated the two controversial events which could have destabilised its reputation with canny calmness, it also sought to honour the commitment of its surgical team in the 1890s. Two years after Garrett Anderson's resignation and nearly seven months after the attack in the Daily Chronicle, Mary Scharlieb and Florence Nightingale Boyd were rewarded with new titles. On 6 December 1894, the Managing Committee considered the Medical Council's recommendations and decided Scharlieb and Boyd should be ‘termed surgeons’.Footnote 101 This was acknowledged publicly in the Annual Report for 1894.Footnote 102 Although most women doctors were still restricted in what they could achieve institutionally, the recognition of specialty was crucial for progression in surgery and for the New's reputation as a primarily surgical centre. As Scharlieb remarked later, this period saw the start of both an immensely successful partnership and the growth of surgical practice at the hospital: surgery became ‘a very marked feature’.Footnote 103 So thoroughly did Boyd and Scharlieb understand each other's ways ‘that is was just like one brain directing two pairs of hands’.Footnote 104 From the divisions of the 1880s and the public attacks of the 1890s grew, according to Scharlieb, an understanding with the advantage of one way of thinking, but two skilful pairs of hands with which to operate effectively. In ‘taking full charge’ of surgery at the New,Footnote 105 Scharlieb bypassed the need for absolute reliance on the consulting staff and, with the confidence of the Managing Committee and dedicated assistants, began to operate independently. From 1893, rather than wavering in its performance of risky and controversial operations after the concerns raised about procedures at the hospital, the competence of its staff and the growing public worries about the wisdom of surgery, the NHW determined to prove its success in promoting the woman surgeon and defending her actions.

The Annual Reports for the 1890s illustrated the growth of risky operations, including bladder, gastric, kidney, liver and rectal procedures, as well as for the diseases of women. Scharlieb described her final ten years at the hospital as providing ‘exacting’ and ‘very interesting’ surgical work, but referred also to the ‘peaceful routine’ which was established, composed of ‘much work, many anxieties, and ample causes for thanksgiving’.Footnote 106 While the New catered solely for women and children, it did not consider itself a specialist institution and always insisted on its status as a general hospital, reflected here in the variety of procedures performed. Patients admitted to the New suffered from ‘general’ complaints, as well as gynaecological ones, and surgical procedures were not confined to specifically female ailments. Experience in surgery was obtained only through practise, and the institution's insistence on multiple attempts before assistance in serious cases helped to hone operative skills. Indeed, the first Annual Report to be published after the change in personnel remarked upon the very good results obtained from a large number of major operations, stressing, no doubt with the problems of 1888 still in mind, the rapport the staff had with their male counterparts, who sought advice from the women surgeons and even placed their own patients under female care for operative treatment.Footnote 107 The stress on co-operation between the women themselves, as well as the trust of male practitioners, focused attention away from the thrusting, selfish and reckless image of the fin-de-siècle surgeon, so beloved of the popular press, and instead towards the fellow feeling existing between professionals and their concern to obtain the best for their patients.

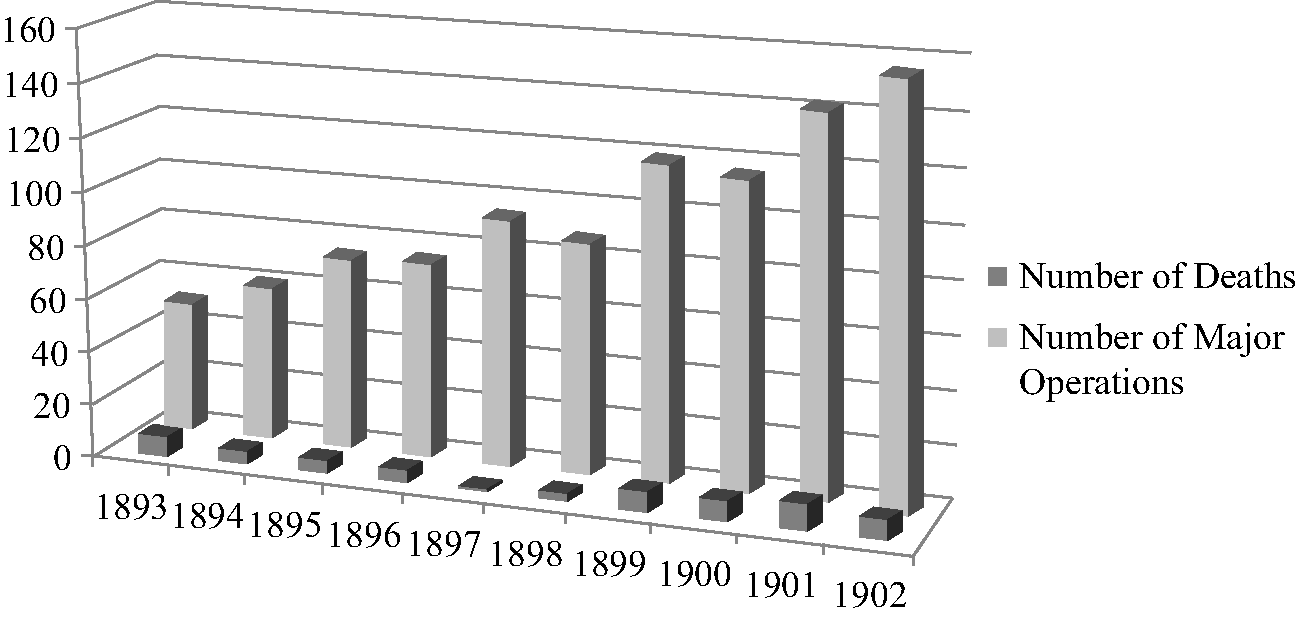

While the hospital had defended itself successfully against the attacks of Blackwell and Bell Todd, deaths following operation, even if they did not occur in the theatre itself, continued initially to rise under Scharlieb. In 1893, the first year of Scharlieb's promotion to senior surgeon, operation deaths were at their highest ever: eight out of 51 major cases. However, for three years – 1894, 1895 and 1897 – there were five deaths out of 59, 72 and 93 operations, respectively; in 1896, there was only a single death out of 74; in 1898, three out of 87; and in 1899, the number had risen to seven out of 118 cases (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Number of Major Operations and Post-operative Deaths: NHW, 1893–1902.

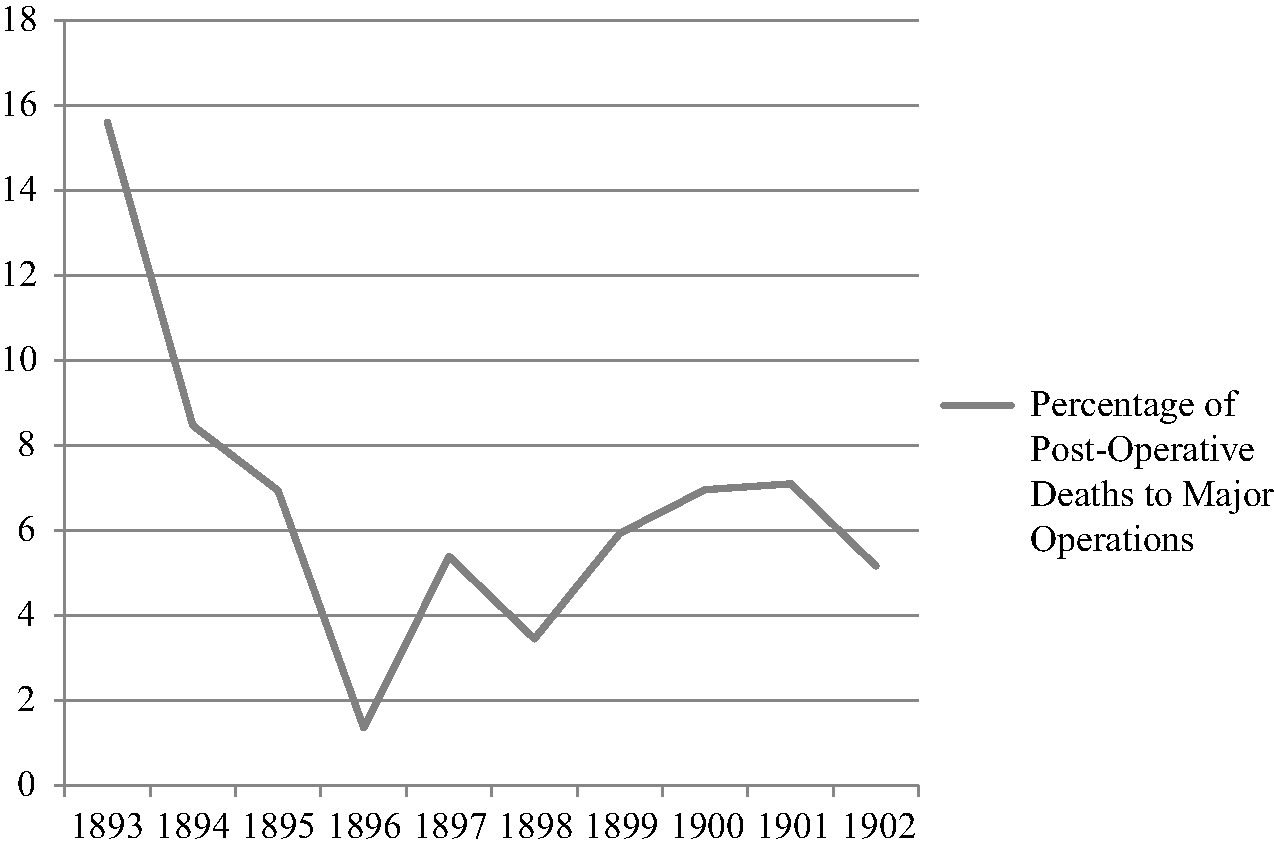

From 1900, there was a distinct correlation between the number of deaths and the number of patient refusals. In 1900, there were eight operation deaths and nine refusals, out of 130 cases; in 1901, ten deaths and ten refusals, from a total of 149 cases; and in 1902, eight operation deaths and seven refusals in 155 major operation cases (Figure 1.3). In 1902, Scharlieb took a coveted specialist post in the Gynaecological Department of the Royal Free Hospital, the first woman to hold such a senior position in a general institution. By the time she left, there were three times as many major operations carried out at the NHW as there had been ten years earlier, but with the same number of fatalities: an impressively consistent statistic. The growing confidence of Scharlieb as a surgeon and the support of her team contributed to an exponential increase in risky operative procedures, but a steadying hand in controlling surgical and post-surgical death. Typically self-effacing about her own abilities, Scharlieb herself attributed survival rates partly to the development of pathology at the hospital, which allowed the surgeon greater accuracy of diagnosis and treatment.

Figure 1.3 Percentage of Deaths to Major Operations: NHW, 1893–1902.Footnote 108