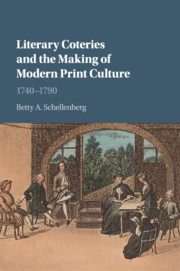

To a Lady on her Love of Poetry. June 8.1747. Wrote by Mr. C. Y—e.

To this point, I have traced the literary lives of individuals such as the Yorke brothers, Thomas Edwards, Catherine Talbot, Hester Mulso Chapone, Elizabeth Carter, Elizabeth Montagu, and George Lyttelton, showing how fluid were the roles of writer and reader – not to mention project instigator, editor, and promoter – in their coterie contexts. For almost all these women and men, print dissemination served at some point as an extension of coterie circulation. They chose print carefully and deliberately, for productions whose wide circulation might increase their literary reputations and in some cases their financial security, but equally importantly, which might broaden their esthetic, intellectual, social, and moral influence. In the most complex case, that of William Shenstone and the Warwickshire coterie, I have suggested how the poet-landscape gardener constructed and articulated a persona and an esthetic through coterie practices which were simultaneously affirmed in transmediated form through the print entrepreneurship of Dodsley’s Collection of Poems by Several Hands. After Shenstone’s death, the resources of the print trade came into greater play through Dodsley’s edition of the Works, preserving the representation of the coterie in the form of the printed book, but also providing the basis for a revision of literary sociability away from the embodied coterie to fulfill the needs of a virtual community of readers in the medium of print as represented by the magazines. In this chapter, I will shift the point of view from producers to such reader communities, as reflected by individuals who created personal miscellanies recording the reading material they considered worth circulating, copying, and preserving.

Margaret Ezell has written eloquently of manuscript compilations in bound book form as “invisible” or “messy,” as “books that look like ‘real’ books, that is to say, like printed books, on the outside, but behave entirely differently for the reader and writer once the cover is opened.” Ezell focuses on very miscellaneous compilations created through to the end of the seventeenth century, those “that combine accounts of rents collected with copies of verses, alphabet exercises with prayers and diary entries,” rather than the beautiful, fair-copy compilations produced by individual authors or scribes.2 My own study group falls into a later period and comprises materials somewhere between Ezell’s miscellaneous compilations and the fair-copy volumes she references. It is comprised of compilations whose content is primarily poetic, in keeping with this study’s focus on the literary coterie. Nevertheless, even the belletristic collections I have examined may display conjunctions of the traditional and the contemporary, the national and the local, the public and the private – in addition to filled-in or cut-out sections where an original or later compiler had second thoughts, and even laundry lists or knitting patterns. Ezell’s point thus remains well taken: such books baffle our print-based habits of reading and resist our attempts at classification and interpretation. At the same time, the access they offer us to an earlier world of reading and producing the literary invites us to make the attempt.

First, the challenge of classification. All the books discussed in this chapter belong to the general category of the commonplace book. In this I follow Earle Havens, who has disputed the notion of a “zenith” of the commonplace book preceding the entrenchment of a print-based literary culture, preferring to consider the form as a “protean” but persistent genre from antiquity to the twentieth century. Scholarship on the scribal practice of commonplacing has in recent decades emphasized its engagement with print from the latter’s rise as a communications technology. David Allan in Commonplace Books and Reading in Georgian England has examined a very wide range of such books, setting as a base criterion for a “commonplace book” some form of engagement with reading materials that involves selection and copying. Allan asserts that, despite the range to be found in the conception and uses of such books in the period, they virtually all owe a debt to the venerable rhetorical notion of the commonplace and therefore affirm “the pre-eminent importance of highly structured and analytical approaches to the consumption of texts.” As noted in my introduction, Peter Beal has downplayed the scholarly interest of eighteenth-century commonplace books of all types in comparison to their seventeenth-century predecessors, “perhaps … because they belong less to a flourishing manuscript culture and because most of what they contain is trivial and ephemeral material copied largely from contemporary printed sources.” But even as such, these books have something historically specific to tell us. Ann Blair and Peter Stallybrass, in “Mediating Information, 1450–1800,” have traced the intertwined practices of print and script in response to what they call a “new cultural attitude” of “info lust,” which increasingly “valued expansive collections of many kinds for long-term storage.” It is not surprising that as reference books and manuscript filing and information retrieval systems proliferated in the long eighteenth century, mundane uses of the commonplace book appear to have diminished, with a remaining emphasis on poems (with the occasional short prose piece) most often copied in their entirety. For many, the commonplace book seems to have become, simply, a “poetry book” or personal anthology.3

These are the sorts of books – labelled “personal miscellanies” by Harold Love – on which my chapter will focus. For Love, the term, in distinction to “commonplace book,” indicates “a class of manuscript books into which the compiler entered texts of varying lengths which were either complete units or substantial excerpts.” Following Love, I will generally use the terms “personal miscellany” or “poetry miscellany” even where these books have been classified as commonplace books in a particular collection.4 In the books of 1740–1800 that I have examined, attention is paid to fair appearance, with generous spacing of margins, implying that paper is becoming more affordable and its use for such purposes more acceptable. At the same time, the books are more decorated, with title-pages and schemes of underlining and bordering often giving them a unified, fair-copy look. Although title or first-line indices continue to be created for many of them, the emphasis shifts from retrievability of information to creating and preserving a collection with personal meaning. The formulation of a nineteenth-century collector underscores the sameness-in-difference of late eighteenth-century personal miscellanies when he writes in the flyleaf of Bodleian Ms Eng. Poet. e.47 that “this book … is the usual poetry book of young people who, at a time when books were dear, copied the poems &c. that pleased them most.” This retrospective view reinforces the continuing principle of selection from reading materials (copying what “pleased them most”) and the practical limitations of access to print that could serve as motivators, while pointing to the narrowly literary character of such collections in the period.

In his study of the Georgian commonplace book as a record of reading, Allan represents reading as a solitary act, a means of individualistic self-construction. Although I rely on a number of Allan’s generalizations in my discussion below, my goal is rather to suggest a methodology for reading the traces of sociable literary culture in personal miscellanies. As Oliver Pickering, the original cataloguer of the Brotherton Collection of eighteenth-century commonplace books at the University of Leeds, has observed, each book has its own story: it is the record of “a unique act of compilation arising out of a particular set of circumstances” and therefore “always more than the sum of its parts.”5 The “particular set of circumstances” out of which at least some of these books arise is, undoubtedly, the life of a literary coterie; the books thus offer a material history of the coterie that produced them.

This chapter’s discussion of six such books compiled roughly within the years encompassed by my study, 1740–90, will paint a picture of how coterie literary practices persisted, but adjusted to the forms and quantity of printed materials available. They did so by favoring the affective over the mnemonic and analytical and, increasingly, by using print to mediate literary sociability. In other words, the increasing availability of books and newspapers leads to diminished use of script to create general reference compendia in favor of collections designed primarily for personal entertainment and edification and to record and sustain the private life of a group. Thus, a study of sociable literary practices as revealed in personal miscellanies also illustrates the strategies by which their compilers negotiated the interface between scribal and print practices in this period. The evidence implies a model of reading directed by the content and formats of print, especially periodical print, which often purports to be selective in itself. Keeping pace with the well-documented increase in numbers and distribution of provincial newspapers and literary magazines in the second half of the century, materials recorded are increasingly copied wholesale from such sources, rather than in organized and digested extracts.6 It is in this sense that the act of selection and copying can be seen as more affective and appreciative than intellectual and educative. Stephen Colclough has argued that the use of printed materials notwithstanding, “such a book was ‘personal’ in the sense that the compiler created an original editorial arrangement of writings by an array of different authors that had originated in a range of different sources. These compilations reveal that their creators assumed the same right to ‘recompose, reapply, add and reorder’ printed texts as they did with manuscript materials.”7

Although his focus is on reading first, Allan further identifies a fundamental link between the commonplace tradition and the practices of imitation and invention.8 Susan Whyman’s concept of “epistolary literacy” is also useful in this regard. In The Pen and the People: English Letter Writers 1660–1800, a study of the uses of letter-writing in families below the rank of gentry, Whyman devises this term to denote a level of reading and writing skill beyond the baseline measure of signing one’s name; epistolary literacy, while considered as a spectrum, minimally entails an ability to form coherent sentences, a knowledge of certain formal conventions, and a capacity to narrate or give order to content. Whyman’s meticulous research demonstrates that such skill had, to a degree hitherto unrecognized, penetrated not only the farthest geographical reaches of England but the social orders even below the middling sort. Whyman includes in her discussion “the use of letter-writing to satisfy literary objectives,” providing ample evidence of correspondents for whom epistolarity went much beyond the merely functional, achieving creative expression and esthetic pleasure through discussion of literary reading, imitative writing, and exchange of copied or original poetry and stories.9 Although Whyman does not invoke the concept of the coterie, it is clear from her case studies that the most highly developed instances of such literary expression were inherently social, occurring between individuals with a long-standing relationship of kinship or friendship for whom literary discussion and exchange were a means of solidifying and developing their common interests.

Literary coteries and the unknown compiler: a methodology

This chapter extends Allan’s observations about the link between copying and invention in the commonplace tradition and Whyman’s conclusions about widespread epistolary literacy to the supposition that a certain number of individuals keeping personal miscellanies would have preserved within them the marks of their participation in a coterie – a network that practiced the composition, circulation, and collaborative criticism of literary materials of its own, as well as the interpretive reception of works obtained from outside sources. This does not mean that such evidence is definitive or easy to interpret: the traces of a group can be difficult to decipher in an individual book, which is generally written in a single hand (or a chronological sequence of hands if the book is used over several generations), and it would be a mistake to suppose that all poetry compilations reflect a sociable literary model. However, like the letters and occasional pieces exchanged within the networks I have discussed in previous chapters, there are materials in some of these compendia that represent activities used to solidify ties between members of a coterie. In this, these manuscript books continue not only a tradition of active reading but also that noted by scholars Love, Arthur Marotti, and Colclough wherein scribal circulation was used by groups to exchange political and religious views or potentially libelous and obscene writings, or simply to hone the prestigious arts of criticism and composition. As in those earlier cases, original poetry is created and recorded to mark positions, values, and occasions of importance to group members, and the ensemble bolsters the identity and perhaps also the social standing of the group. The typical subject matter of such materials retains strong elements of political satire, spiritual reflection, assessment of relations between the sexes, and expressions of friendship. The genres favored – such as extempore poems, epigrams, riddles, epitaphs, elegies, and above all, occasional poems – are related to various mnemonic or memorializing gestures and therefore to the generalized functions of much eighteenth-century coterie writing.10

The remainder of this chapter will provide a detailed analysis of personal miscellanies which display these marks of a sociable origin in varying degrees. The following are features I have used to identify coterie activity (in ascending order of significance) in the manuscript books I have examined:

1) Materials by multiple authors – whereas some manuscript compilations given the label of commonplace books nevertheless appear to contain only the compiler’s original compositions, perhaps intended for circulation, this does not show indication of collaborative production and discussion.11

2) Contemporary materials – while all books I have examined contain at least some older poetry, active coterie circulation will involve the production and discussion of new literature as well.

3) Material likely obtained through scribal circulation – poetry which, even if ultimately printed, plausibly originates in scribal exchanges rather than print sources, as evidenced by its earlier dating, its variants from printed versions, or its authorship by persons who are known to be part of the same social network.

4) A mix of materials copied from print and original writing – the former are generally easiest to identify, even when not attributed, and often make up the majority of such books’ contents; the latter may be attributed explicitly to the book’s compiler or another coterie member, but more often will be veiled with “By a Lady” or a title invoking persons and places that can be related to the compiler in some way. An instance would be the poem titled “To Eliza’s Portrait,” attributed to “Scriblerus June.1789,” in Eliza Chapman’s book, which is discussed below. When such a mixture demonstrates interaction between the copied and original elements – such as thematic clusters of printed and original poems, or the incorporation or imitation of printed poetry in original poems – it most fully reflects the life of an eighteenth-century literary coterie as I have characterized it, involving both critical response to shared reading and the collaborative production and circulation of writing within the group itself.

5) Material with a clear occasional and local reference – again signaling originality, but also mapping relations between group members onto a spatio-temporal context; an example would be the date of the Scriblerus signature above, or in Eleanor Peart’s book, the pair of poems titled “To My Sister Mary on her Nuptials with The Right Honorable Lord George Sutton Solemniz’d the 6th of February 1768” and “To Miss Ela: Peart on the marriage of her Sister the Right Honble Lady George Sutton February the 6th 1768 by Miss S: Bate.”

6) External corroborating evidence of coterie activity – in the case of books attached to named, known individuals or books referred to in extant correspondence.

These features will frame my discussion of three manuscript books from the Brotherton Collection held in the University of Leeds Brotherton Library and three from the Bodleian Library of Oxford. All were compiled by individuals or families about whom we know little – in one case, not even a name. This allows me not only to consider the perspective of the writer as reader but also to shift the focus of this study from writers who are well documented in the historical record, generally by virtue of their participation in some form of public life, to those who are obviously educated and of literary tastes, but who represent the larger, more obscure proportion of participants in contemporary literary culture. In this discussion, the personal miscellany figures as a site of interface between the coterie and print; more broadly, the case studies in this chapter reveal the variable configurations of reader-as-author within a shifting media ecology. Rather than provide an argument about changes in the miscellanies over this period, however, I will offer snapshots of how literary sociability manifested itself in personal poetry compilations of the period. Above all, these examples will serve to demonstrate that despite changes in source materials, the appeal of the literary coterie, whether for aspiring urban professionals or for family and friendship circles in country neighborhoods, appears to have been a constant.

Mary Capell’s “Sacred Book”: situating and reading a personal miscellany

My first example serves as a bridge between the well-documented Yorke–Grey coterie discussed in the first chapter of this book and the unknown literary life of a young woman of the aristocracy in the 1740s and 1750s. The evidence provided by this book thus not only enriches what we know from the correspondence record about this coterie but also suggests how such a coterie’s literary influence might spread to those connected in some way to its members. Brotherton manuscript Lt 119 is an octavo-sized, calf-bound volume of eighty-seven poems copied entirely in the hand of Mary Capell, who has written her name on the first folio of the book, created an index, and supplied dates as well as attributions written on the verso side opposite most items. Capell (later Lady Forbes) was the niece of Henry Hyde, Viscount Cornbury, whose attachment to Lord Bolingbroke, and thence to the Opposition to Walpole, brought him into contact with Alexander Pope and Charles Hanbury Williams, chief manuscript satirist of the Whig interest. Thus, Capell seems to have had access to poetry available only through scribal circulation, such as several Cornbury poems that open the volume,12 Pope’s portrait of Atossa (added to his Epistle to a Lady only in 1744), and Williams’ satires. Laura Runge notes the political flavor of the collection, what she refers to as “poetry concerning public affairs related through intimate knowledge of the great men in government.”13 Capell’s correspondence with Thomas Birch, preserved in the Birch papers in the British Library, indicates indeed that such public interests were also her own, related to her family and its Whig tradition. In 1751, Birch sends her manuscripts regarding the alleged fraud surrounding the birth of the Old Pretender and regarding the report of a committee of the House of Lords investigating her great-grandfather’s death; she in turn asks him in 1756 for biographical information related to a set of seventeenth-century portraits she seems to have inherited, perhaps at Cornbury’s death in 1753, and thanks him in November of 1756 for his account of “the new Kissing-Hands” (that is, the newly formed Ministry), with which she is not very pleased, except for “the Preferment in the Law, which happened some Little time before The Last Grand-Change” (likely a reference to Charles Yorke’s recent elevation to Solicitor-General).14

The latter comment, moving fluidly between public and private interests, is paralleled in the book’s contents. The miscellany’s relation to the Yorke–Grey coterie is written into its pages, with poem headings such as “Daniell Wray Esquire. Anagram Is Weary, queer, and ill. 1747 – Wrote by Mr. C—Y—e [Charles Yorke],” “Sonnet wrote at the entrance of a Root-House in W—st [Wrest] Gardens. 1751. Wrote by Mr. E—ds [Edwards],” and “To the M—ss of G—y [Marchioness of Grey]. By the Honble. Miss Margt. Y—ke [Yorke]. 1747” that celebrate the central members of the coterie and its physical heart of Wrest Park. All dates provided for poems in the collection fall between 1740 and 1751, encompassing the period of the Yorke–Grey coterie’s most active literary production. The miscellany contains thirteen poems attributed to Charles Yorke, at least three by Thomas Edwards, and others by persons more peripherally connected with the Yorke–Grey circle, such as Isaac Hawkins Browne, George Lyttelton, and Soame Jenyns. Attributions that can be added to Capell’s own confirm the Yorke–Grey connection: two of the Edwards sonnets – his poetic attack on Warburton (“Tongue-doughty pedant, …”), first printed in 1750, and his reflection on the loss of all his siblings (“When pensive on that Portraiture I gaze, …”), published in Dodsley’s Collection in 1748 – are unattributed in the Collection and here, but their origin and circulation can be traced in the Yorke–Grey correspondence.15 The third last poem in Capell’s collection – “Blest Bard! To whom the Muses weeping gave/That Pipe, which erst their dearest Spencer won” – is the Hester Mulso tribute to Edwards that Thomas Birch sent Capell in the exchange already noted in Chapter 1, and discussed further below. Thus, the multiple authors represented in the volume, while including writers widely known in the period, such as Pope, Thomas Gray, Lyttelton, and Williams, create a networked cluster organized into ever-smaller, denser concentric circles, from the anti-Walpole opposition of the 1730s and early 1740s to which the compiler’s uncle and her brother’s future father-in-law Williams belonged, to the loosely interconnected networks of wits surrounding the Yorke brothers, to the inner circle of Charles Yorke, Jemima Grey, Margaret Yorke, and Thomas Edwards.

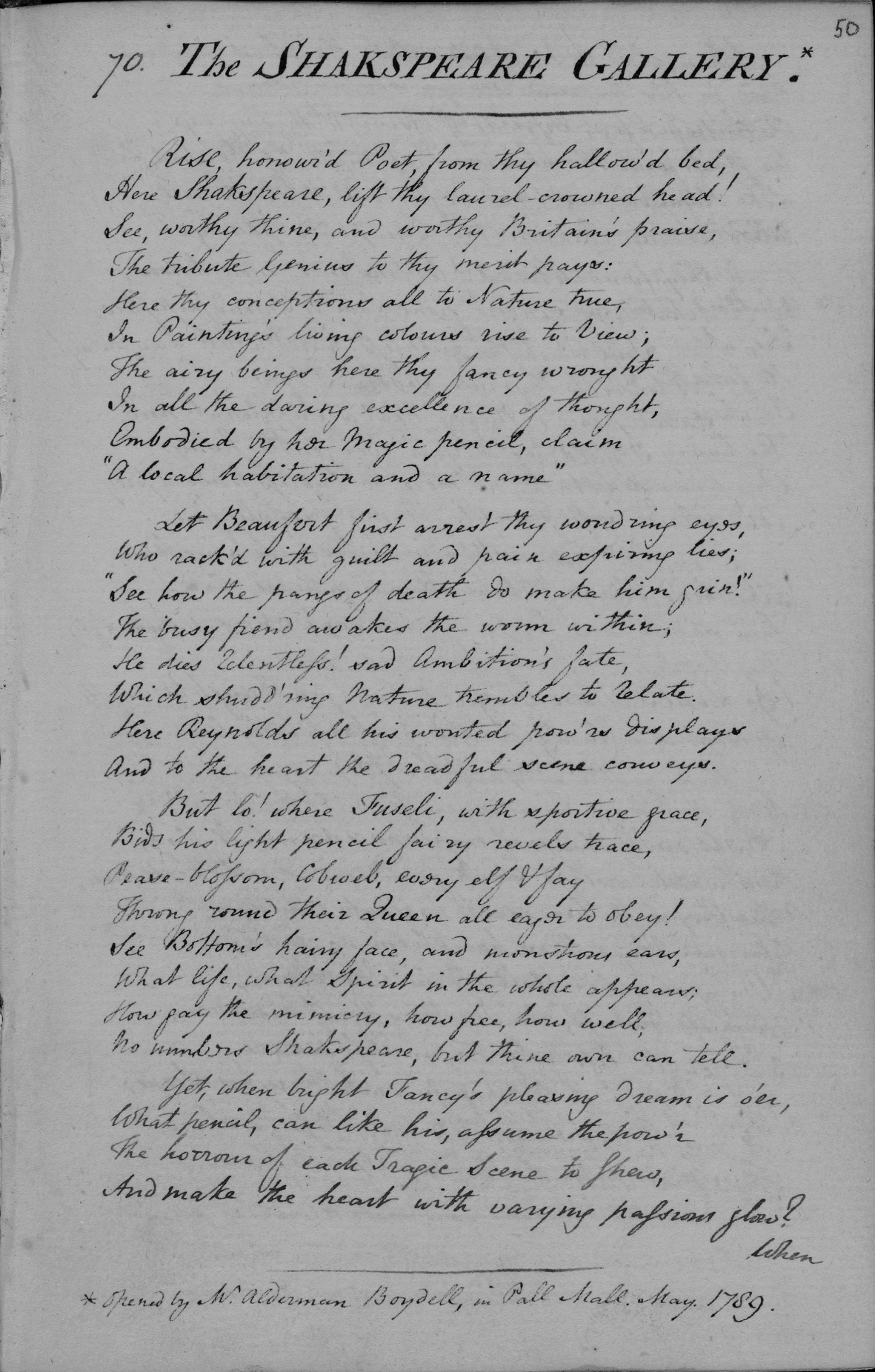

This concentric structure of varying densities offers a material record of how a literary coterie might form, in the 1740s, out of a complex set of familial, political, and demographic connections. Epistolary evidence links the Capell sisters with Jemima Grey from the time before her marriage, when Grey mentions them in a note to Talbot; through the 1740s when Mary Capell toured the Duke of Bedford around Wrest in its owners’ absence, and the 1750s when the Capell–Birch letters refer familiarly to the teething of Grey’s daughter Amabel and to Grey paying a debt to Birch on Capell’s behalf; all the way to 1780, when Mary Capell as Lady Forbes introduced the second Yorke daughter to her future husband.16 This suggests that not only poems by members of the Yorke family, such as one by Charles to his father the Lord Chancellor, but also others on political themes, like the facetious Jenyns poem commiserating with Philip’s relief at having emerged from his latest round of electioneering, came to Capell through direct contact with members of the circle. A 1747 flurry of courtship poems by Charles Yorke – including the one quoted in this chapter’s epigraph, addressed “To a Lady on her Love of Poetry. June 8 1747” (Figure 7.1), and several praising the fair “M—a” (presumably for “Maria”)17 – hint that Capell might for a time have been the object of his attentions (Charles’s first marriage, to Catherine Freeman, did not take place until 1755).

Figure 7.1 From Mary Capell’s personal miscellany, “To a Lady on her love of Poetry. June 8, 1747. By Mr. C. Y—e.”

It would not be surprising if Capell’s own literary talents extended to composition as well as appreciation. The third poem in the collection, “Care Selve Beate, in Pastor Fido, imitated,” is recorded as “Wrote by a Lady,” as are three other early items, including “A Letter from Abelard to Eloisa Copied from the original Manuscript”; the cataloguer of the manuscript suggests that all these poems are the product of Capell’s pen. But whatever the case for original composition, Charles Yorke’s address “To a Lady” who “With pains unwearied, in her bloom of Age,/In faithful Volumes … records our Songs” indicates not only a young woman well known in her circle for her appreciation of poetry but also the role such an individual’s commonplacing could play in a sociable literary network. Birch’s manner of expression in sending her several poems for her “Sacred Book,” first quoted in Chapter 1, further articulates this recording role:

Mrs. Heathcot’s18 Verses to Lady Grey are accompanied by a very fine Ode, which I mention’d to your Ladyships, of Miss Mulsoe, address’d to Mr. Edwards on Occasion of some of his Sonnets in the Style & Manner of Spenser, particularly one to Mr. Richardson, prefix’d to the last Edition of his Clarissa. It was communicated to me under the Restriction, of not multiplying Copies: But I cannot deny it the Honour of a place in Lady Mary’s Quarto, which consigns such pieces to Immortality.

Capell replies that “Miss Mulsoe’s Ode, & that of Mrs. Heathcote, we were much pleased with, & I have copied them into the Sacred Book; As also The Report of the Comittee, & the Letter to Coll: Southby.”19 Clearly, Capell’s commonplacing of poetry gleaned from her social networks was endorsed as an integral element of coterie life. As a result, Capell’s “Sacred Book” reveals a great deal about the circulation of manuscripts in the Yorke–Grey coterie and the more extended networks with which it overlapped. It provides us with a window into a very active site of literary production and exchange, almost completely separate from the world of print, one in which it is in the power of the reader-compiler to “consign[] such pieces [as Mulso’s] to Immortality.”20

Thomas Phillibrown’s London coterie

A very different sort of coterie from precisely the same time period is reflected in the personal miscellany of Thomas Phillibrown, Jr., held in the Bodleian Library of Oxford University.21 Of more modest social status than Capell, Phillibrown was a man of business based in London who found it important to contextualize his own life in relation to the public worlds of contemporary politics and the arts. In the former case, he created a book he titled “A chronological & historical Account of material Transactions & Occurrences in my time” which covers the period from March 26, 1720 (apparently his birthdate) to December 5, 1758. According to Phillibrown’s own elaborate title-page, he uses “Salmon’s Chronological History. Vol. 2d. the 3d ed. publish’d. 1747” to supply a list of events such as Lord Mayors’ elections and processions, theater riots, the building of public works, and developments during the 1745 Rebellion into which he inserts his own eyewitness vantage points.22 Conveniently for the researcher, this book also provides external corroboration of Phillibrown’s artistic life. Phillibrown valued his connections with writers, musicians, and other artistic professionals – or aspiring professionals – enough to record their exchanges and productions in a second book he entitled “Miscellanies” and dated March 11, 1740/1 (although its dated entries precede this point by several years and continue into the 1750s). The recurrent attributions – these include John Hawkins (later Sir John), Moses Browne, William Boyce, John Pike, Richard Dyer, Foster Webb, and one or more “Mr. Scotts” – together with the nature of the book’s contents create a portrait of an urban coterie of young men perhaps not very different from William Shenstone, who at this time was frequenting London theaters and coffee-houses hoping to meet influential people and overhear discussions of his most recent poem, or Samuel Johnson, who was similarly seeking to make his way in the London print trade.23 There are copies of verses on “‘The Life of a Beau.’ Sung by Mrs Clive,” “On Mr Quin—by Mr Foster Webb,” with a side-note referencing the 1743 theater quarrels between Thomas Sheridan and Theophilus Cibber, and “From ye Daily Advertiser Augt:4:1743” a copy of verses “To Cydonia. An Invitation to Vaux-Hall-Gardens” attributed to R. (Richard) Dyer.

While it is likely that a number of these items were copied straight from the magazines because they appealed to the compiler for some reason, at least some of the entries provide a backstory to their printing, thereby offering a glimpse into the scribal system to which the magazines were linked. Thus, an essay “On Politeness. To the Author of the Westminster Journal … By Thomas Touchit, of Spring-Gardens, Esqr” is attributed to “J.H.” (Hawkins) and copied along with the contributor’s cover note and an unsigned acknowledgment from the editor inviting “the Repetition of such Favours” (f. 22); a similar letter signed by Edward Cave and dated December 16, 1740, is headed “To Mr John Hawkins on his having sent severall Dissertations to the Gent: Magazine.” A later item carries the headnote “Horace. Lib.1.r Ode 34 paraphrastically translated By Mr Foster Webb. pub. Gent. Mag. 1742 page 46.” At least one of the several periodical essays attributed to Hawkins notes the price paid to him for the submission. Other paratexts further demonstrate how periodical publication was linked through coterie networks to other commercial artistic enterprises; for example, the entry headed “Daily Adv:r Saturday Feb:21:1741. To Mr John Stanley. Occasion’d by looking over some Compositions of his lately published” carries the explanatory note “made by Mr Jno Hawkins” and an identification of the Stanley work in question as “Eight Solo’s for a German Flute.”24

But there is more to the coterie‒magazine interface than simply the movement of copy from one medium to the other: the two mirror one another as systems of conventions and social practices. An entry I have not found in a magazine source presents the quatrain

as “Spoken extempore” by “J.M.” – reflecting typical coterie appreciation of verbal wit. Yet such an entry is just as likely to originate not from a coterie but from a periodical, as in the case of “From ye Gent: Mag: 1731. The following Verses were found written in ye window of Miss Fanny Braddock at Bath. a Lady of 6000£ Fortune who Hang’d herself in a Girdle Sept 8:1731 haveing met with unlucky Chance at Gameing,” which is followed by an extempore imitation, also taken from the same article, by a gentleman who addresses “O Dice!” where the unfortunate lady had apostrophized “O Death!” On another occasion, Phillibrown records an epigram titled “Mr. C—y’s Apology for knocking out a News-boy’s Teeth” as by “A.B.” and signed “T. L—an,” a double attribution that miscopies the Gentleman’s Magazine’s attribution of the poem to “T. S—an” (that is, Thomas Sheridan), while at the same time hinting at insider knowledge of the poem as composed, or submitted to the magazine, by “A.B.” Print in these cases is not so much a source of the miscellany’s materials as a single element in a complex pattern of circulation.25

In other words, such printings, misattributions and all, likely originate themselves in the wide circulation and preservation in the commonplace form of admired poetic performances. Thus, a poem in Phillibrown’s book bringing the twelve signs of the zodiac into the compass of ten lines celebrating “a Zodiack of mirth” does not appear in the Gentleman’s Magazine but turns up in sources well into the nineteenth century in association with John Flamsteed (or Flamstead), the seventeenth-century founder of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich; Phillibrown gives it the headnote: “Mr Brown [perhaps an attribution to the legendary Restoration rhymer Thomas Browne] being at an Entertainment at Dr Flamsteads, ye famous Astrologer in Green-wich Park & was desir’d to divert ye Company with something extempore, upon which he pen’d the following Lines.”26 Intermediation works both ways: manuscript-exchanging networks serve as the origin and site of extempore poetry-making, while print complications such as the Gentleman’s Magazine reinforce and propagate such practices. In this way, Phillibrown’s book demonstrates that Ezell’s description of the coterie‒periodical equilibrium of the 1690s remains apt fifty years later: “the old shell is not discarded but adapted, permitting the essentially communal and reciprocal principles of coterie, amateur literary practices to flourish in the new commercial medium, giving vitality to the new shape while sustaining the social dynamic of the old.”27

Even the direct interactions between members of this urban coterie can be transmediated. In one case, “A Song by Mr John Hawkins Set to Musick by Mr Boyce Organist to the King’s Chappell at St. James’s” is followed by two letters from Boyce responding to the unknown author’s publication of the lyrics he has set. In another case, Phillibrown follows a transcription of the John Donne sonnet “For Godsake hold your Tongue, & let me love” by a pair of imitations attributed to “Mr Foster Webb 1741” and “Mr J. Hawkins 1741,” and then notes that “Mr. Hawkins sent the 2 foregoing Sonnets No 1&2 to Mr Moses Browne (a very ingenious Author of several Poems, & who won most of ye prices [sic] in ye Gent. Mag. & some time stiles him self under ye Name of Astrophil) desireing his Judgement upon them.” Browne’s relative position in the authorial hierarchy here is signaled by his print-based recognition.28

As in the case of Mary Capell’s own poetic impulses and the possible role of Charles Yorke’s romantic interest in her literary life, it is difficult to determine which works, if any, in Phillibrown’s miscellany offer hints of his own literary attempts and the changing profile of his coterie over time. Although no entries are explicitly identified as his compositions, the book takes such pains to provide sources for many of its entries that it is plausible to suppose at least some of the items for which it remains silent are by Phillibrown himself. For example, in the very early folios of the book there is a thematic series on death and the afterlife framed by two accounts of suicide taken from The Old Whig and The Gentleman’s Magazine (cited above). Within this frame are found a transcription of a birthday prayer of gratitude, “In Diem Natalem – by Miss Carter of Deal,” suggesting access to the poem before its print publication in 1738, and a couple of unattributed poems – “On Purgatory” and a verse translation of the Latin “Ne sis tantus cessatur, ut calcaribus indegeas,” which carries the tag “Done as an Exercise at Trinity-College, Cambridge.” Other tantalizing hints are several items signed “T.F.,” perhaps for “Thomas Phillibrown,” including one dated 1754, more than a decade after the dates of most of the compilation’s items.

A series of generally positive items related to Dissenting preachers and the Dissenting burial ground of Bunhill Fields correlates with the “chronological & historical Account’s” records for the early 1750s of the preaching of John Wesley and George Whitefield. In one case the miscellany compiler goes to great lengths to bring his personal experience and connections into a headnote that becomes almost a biographical retrospective:

The Fire-Side; by Dr Cotton, of St Albans. Dtor Cotton Married the Elder Sister, of my Old Schoolfellow Mr George Pembrook, of St Albans. She was a Beautifull, fine Young Lady; when I was at School at St. Albans in ye Years 1728, 1729, & 1730. She was highly admired by all our School Boys, & went by the universal Title, of the pritty Miss Pembrook. Happy was he! who was favour’d with being in her Company; which Honour I my self have been favour’d with several times, at the House of my Dancing Master Mr Donvill at St Albans; at whose House we used to prepare for, & keep our Balls. And with which Lady I have had the pleasure to Dance in particular the Chain-Minuet; as well as various Country Dances &c. at our several Meetings at the Above Dancing Master’s House.

The following Lines, my Brother Copyed in the Study of the Revrd. Mr Folliot, Dissenting Minister of St. Edmonds Bury 1755. Mrs Cotton has been Dead some Years, & left several Children. The Revd. Mr Folliot Died in the Year 1756.

I Copyed ye following, from my Brother’s. Manuscript; March 21. 1757.29

Equally informative with regard to Phillibrown’s literary affiliations is the distribution of materials in his collection: the works recorded appear fairly miscellaneous in their attributions until roughly halfway through the entries, when Hawkins first makes his appearance in the above-mentioned letter from Cave, dated December 16, 1740. It is from this point on that Hawkins, Webb, and Pike become regulars in the book, suggesting the formation of a literary coterie. Webb’s untimely death in February 1744 at the age of twenty-one is recorded in the form of several notes and a copy of Hawkins’ character of his friend, published in the Gentleman’s Magazine; this event seems to signal the demise of this circle. It is at this point that later entries in the book, after an apparent gap of about five years, include comparisons of, anecdotes about, and poems by Dissenting ministers of the London area. Some of these are in a later, larger hand, often glued over earlier items from the coterie portion of the miscellany, such as “Fritters Misused by Mr. Scott” and “Mr. Scott on ye loss of his Cloaths,” whose titles in the index suggest frivolity.

The personal miscellanies of Mary Capell and Thomas Phillibrown, then, record a mid-century coterie culture that was active in both elite and middle-class circles, and in which multiplex social, political/religious, geographical, and literary links reinforced one another. They also demonstrate the facilitating roles played by both material and associational factors, whether country houses, schools, London-based publications such as the Gentleman’s Magazine, Dissenting culture, or Whig alliances, as what Bruno Latour would designate “actors” in the creation and form of social networks.30 Phillibrown’s personal miscellany offers the further confirmation that the world of print was not in tension with coterie networks; rather, printing provided an outlet for the literary productions of coterie members and was a source of pride, suggesting that it was seen to further the standing of the group. This interface with print appears most seamless and direct in the case of periodical forms, however; Phillibrown’s manuscript does not appear to include excerpts from any anthologies or books. In my remaining discussion of poetry miscellanies compiled by obscure individuals later in the century, periodical literature will be found to continue in its central role, even in some cases becoming the mediator of coterie culture itself. Whereas in the Phillibrown book the periodical press functions primarily to extend and enhance the sociable literary exchange of his coterie, in some of the cases discussed below, materials from periodicals serve as the stimulus of coterie production, or even suggest the possibility of a farflung “virtual coterie.” At the same time, anthologies such as Dodsley’s Collection or printed volumes by popular poets like John Langhorne take their place alongside the periodicals in influence.

“Friendship the Artless Song Admir’d”: the Peart-Bate coterie records itself

In 1768, somewhere in the neighborhood of Stamford in Lincolnshire, a young woman named Sally Bate, aged about eighteen years, was invited by her sister Arabella to recount how she became a poet. Responding to “Stella” in the voice of her coterie persona “Hebe,” Sally offers a variation on the story of origin well rehearsed by poets such as Pope (in his Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot), explaining that in her twelfth year the pastoral beauty around her inspired her to compose verses, but that it was her intimate social connections that nurtured her poetic development:

The chain of Sally Bate’s verses, along with those of Eleanor Peart and Peart’s brother Joshua, is preserved in the Bodleian Library as Ms. Eng. Poet. e.28, titled “A Collection of Poems by various Hands, but chiefly by Mr Peart, and Miss Sally Bate and Copy’d out in this Book by Miss Eleanor Peart in 1768.”31 Although the kinds of external corroboration available for the Capell and Phillibrown miscellanies do not appear to be available for the Peart–Bate circle, this coterie displays a strong predilection for poetry that is not simply occasional – that is, commemorating privately significant events through titles and headnotes – but downright autobiographical, as represented by the Sally Bate poem cited above. In addition, this group’s writers feel no compunction about displaying their love of versifying, openly acknowledging their own and their addressees’ identities. Even a love of pastoral names can only partially obscure these, given the regular repetition of “Hebe” and “Stella,” already noted, and also “Damon” (Joshua Peart), “Diane” or “Diana” (another name for Arabella Bate), and “Flora” or “Ellen” (Eleanor Peart).

As a result, much can be learned about the coterie simply from what its members tell us. In addition to their geographical location in the area around Stamford, references in their poetry reveal links to the locally influential Earl of Exeter and Duke of Rutland, and thence to area MPs and landowners. Nevertheless, the poems in the collection begin with hints of tragedy and misfortune: a friend is dangerously ill; a Mrs. Bate, perhaps mother to Sally and Arabella, dies; the Peart siblings (there are five of them: Elizabeth, Anna, Mary, Eleanor, and Joshua) have experienced hardship; several of the sisters seem to be living with an uncle while Joshua is studying the law in Lincoln’s Inn. A joyful change ensues in late 1767 when one of the sisters, Mary, is chosen by Sir George Sutton, third son of the Duke of Rutland, as his future wife, establishing a new center of poetic and sociable pleasures at Kelham, the couple’s home. Much of this information is communicated through the verse epistles the group takes pleasure in composing. The most generically self-conscious of these, “A Versical Letter from Mr Peart to his Sister Miss Eleanor Peart, Written Octo the 29th 1767,” begins:

The fluid, if not especially refined, versification of this epistle speaks to the ease with which the coterie’s members move into the poetic idiom, and also to the confidence they feel that their audience’s social pleasure will be enhanced by the wit and skill of such metrical communications. A similar effect, presumably, would have been achieved when Eleanor Peart accompanied her gift to Arabella Bate of “an Elegant Book” in which to write her sister’s poems with verses in praise of both sisters, concluding:

Given their confidence and pleasure in celebrating their own coterie life through poetry, members of the Peart–Bate circle initially appear less dependent than Thomas Phillibrown on inspiration from the larger world of print. This impression, however, is somewhat deceiving – what we see here is an ingrained habit of imitation that does not require explicit highlighting. I have already noted the coterie’s reliance on pastoral models for conveying poetic inspiration and sentiments of friendship, especially in Sally Bate’s case. In a more particular case, her long 1768 heroic-couplet poem “The Butterfly, the Snail, and the Bee,” addressed “To Modern Travellers,” explicitly invokes Aesop’s fables, but also echoes the satire in Book IV of Pope’s Dunciad of the young man returned from the Grand Tour who has “saunter’d Europe round” and “gather’d ev’ry Vice on Christian ground”:

Bate’s butterfly also visits Hagley, the Leasowes, and Stowe, and the author would certainly have been aware of contemporary celebrations of the gardens and poetry of Lyttelton and Shenstone. In fact, one of the relatively few publicly circulated poems Eleanor Peart includes in her book is “The Squirrel’s of Hagley Park to Miss Warburtons Squirrel by Lord Littleton. – in 1763,” followed by “The Answer,” dated May 17, 1763.33 While a mildly moralizing satire by Lyttelton of his roving son Thomas, now affianced to a Miss Warburton, the poem seems to serve in this collection as a preamble to the next poem but one, “An Epitaph by Mr Peart on my favrite Squirrel being drown’d in a Tub of Water – 1763,” a similar effort at moralizing that combines the theme of women’s domestication of squirrels with allusions to Gray’s famous caution, in his “Ode on the Death of a Favourite Cat,” against undisciplined desires in the female sex. In a final example, when Sally and Arabella Bate exchange a series of poems on the subject of the dangers of love for women, Arabella absorbs several lines from a popular contemporary poem by John Langhorne, redirecting to her own interlocutor the lines “With sense enough for half your sex beside,/ With just no more than necessary pride,” addressed by Langhorne to Mrs. Gillman.34 In other words, this poetic miscellany, like the others discussed in this chapter, preserves acts of poetic creation and exchange that are fully embedded in the broader literary culture of the period, one that is encountered largely through print sources. As noted by Colclough, the coterie’s members make that culture their own through their acts of arrangement, application, and recomposition.

An Oxford gentleman: print-mediated sociability

From the detailed and explicit self-representations of the Peart‒Bate coterie, I turn now to a collection on the opposite end of the spectrum, whose traces of literary sociability are mediated by, and perhaps even exist solely in, printed forms. Brotherton manuscript Lt 99 is somewhat of a tangle, in that it may be the work of at least two unnamed compilers whose hands are not easy to distinguish and whose entries are interwoven. Nevertheless, the materials seem to have been collected in the relatively condensed period of c. 1770–89 and are similar in nature, so whether the book was produced by two simultaneous contributors or two in close succession, with the second filling gaps left by the first, I will discuss it as a whole. The book has a title, “Old Songs & other Poems,” which characterizes the main items, and indeed, the collection begins with a series of songs, ballads, and versified psalms, some accompanied by parallel translations into Latin and others entirely in Latin. Elaborate footnotes to the first poem include a discussion of coping with deafness based on “Experience and Reason,” the second and third poems represent old age from two different women’s perspectives, and the speaker in “Advice to Chloe” asserts that love may endure to old age, all together suggesting the compiler’s advanced age. Interspersed with the poems are many miscellaneous epitaphs, riddles, and short prose pieces. The overall impression is of the kinds of word games and themes of interest to a man of some education, pursuing miscellaneous subjects – good and bad wives, memorials of heroic men, Roman medals, living a good life, and the deaths of humble folk – though none to great depth.

There is, however, a more specific contextual reference point unifying the compilation’s otherwise disparate contents: many items are explicitly associated in some way with Oxford University, beginning with “The Admonition” of a college bursar and “A la Doggrel,” a facetious Latin response attributed to Herbert Beaver, a mid-century chaplain of Christ Church known for his humorous poetry, and including a parody of Gray’s Elegy, set at dusk in an Oxford college, ascribed to Thomas Warton but in fact by John Duncombe. Some of these pieces are good candidates, in their occasional and specific referentiality, for traditional practices of manuscript circulation among networks of current and former students. These might include a riddle prefaced by the note “The following Ænigma was sent by Mr Beaver in return to a friend for a barrel of oysters with these lines … ,” a mock-archaic poem headed “Verses in the Pump-Room at Bath. Said to be written by a Gentleman of Oxford”; the Gray parody (which varies from other versions of the same poem); and a series of six poems dated December 1777 to January 1778 arising out of a recent scandalous ball at Oxford.

In earlier decades, such materials would have signaled an Oxford-based scribal coterie resembling that of the Yorke brothers’ Cambridge circle, and there is evidence in the volume to suggest that this is likely the source of some of the materials. One of these is a prose piece entitled “Memoirs of Mr. Edwd. Thwaites” at the end of which is noted “Taken from a Letter of Mr Ballards, by Memory.” This Mr. Ballard is presumably George Ballard, the Oxford antiquarian who had died in 1755. Mr. Thwaites is described as a man of great learning and personal attractions, but the main focus is his courage during the amputation of his leg, and the fact that upon hearing of this, Queen Anne made him present of £100, and appointed him Greek Professor. A letter presenting essentially the same information but in altered phrasing and sequence is printed in John Nichols’ 1814 Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century as “a few anecdotes, addressed by Mr. Brome to Dr. Charlett soon after [Thwaites’s] death” in 1707, suggesting that this material circulated in several variants early in the century and was perhaps rediscovered and recirculated by Ballard.35 About one-third of the way into the collection, however, the occasional attributions (like those to Beaver and Warton, but also to Dean Swift and Lord Chesterfield – the latter probably spurious) give way to explicitly named magazine sources: The Christian’s Magazine, The Lady’s Magazine, The Critical Review, The Reading Paper, The London Chronicle – this compiler was not choosy. Near the end of the book, two anthologies put in an appearance as well – “Fuller’s Worthies London,” presumably the three-volume “History of Worthies of England,” first published in 1662, and “Nicholls Poems Vol 2d,” a 1780–81 anthology from which the compiler copied a 1700 poem, “An Hymn by Mr Chas Hopkins About an hour before his death, when in great pain,” which had been reprinted frequently throughout the century. These attributions cast backward doubt on the apparent scribal provenance of some of the earlier materials, which might have been obtained through anthologies and, especially, periodical publications, of which this compiler appears to have been a diligent reader. As already argued, however, the increasing importance of newspapers and magazines as sources for miscellany entries does not obviate the expressive potential of acts of selection. Thus, in the case of the “Oxford” gentleman copying the Hopkins poem, although he provides “Nicholls Poems Vol 2d” as his source, these verses also appeared in The Student or the Oxford and Cambridge Monthly Miscellany of 1751. Given the fact that this is the final complete item in the book, it is tempting to imagine that the compiler was recalling the poem from his youth when, on “March 9 1787,” the date he inscribes at the end of the poem, some circumstance of his own led him to retrieve a century-old expression of faith in the face of pain and approaching death.

In this way enigmatic notations such as the dating of a poem can be taken to point to significant events in the compiler’s life. A converse effect of the increasing reliance on periodical sources for commonplace entries, however, is an obscuring of chronology: although the magazine sources cited generally include a date, this appears to serve as a finding aid, rather than as an indicator of the date on which the material was actually read and/or copied. The publication dates provided in Lt 99 proceed in a slow and zigzagging fashion from 1776 to the late 1780s, while interspersed undated material can be traced to publication as late as the time of copying or as early as 1640. Thus, a broader implication of this fundamental shift toward periodicals and anthologies as sources is to put pressure on the very definition of the coterie as a temporally located formation. One might argue that like those readers who came to know and love “Shenstone” through Dodsley and the magazines, discussed in Chapter 4, the unknown compiler(s) of Lt 99 participated in a disembodied and atemporal community, a virtual coterie, mediated by print and loosely linked by an interest in matters pertaining to Oxford university.

Eliza Chapman and Mrs. C. W—ll: coteries engaging print

If my discussion of the Oxford gentleman implies a historical shift away from the embodied literary sociability that I have used to define the scribal coterie, such a conclusion would be premature. For my final two examples of this chapter, I have chosen compilations from the very end of my study period that paint a much sharper picture of literary sociability, despite the fact that their chief compilers are, again, essentially unknown.36 Like Mary Capell, Thomas Phillibrown, and Eleanor Peart, Eliza Chapman chose to identify herself with her book, preserved in the Bodleian Library as Ms. Montagu e.14: she entered her name along with a finely drawn device on the flyleaf (Figure 7.2) and gave the volume a title, “Poetry, Selected and Original. 1788 & 1789.” (The book in fact also includes poems dated 1790 and 1793, copied in the same hand, which are written into the opening pages of the volume and to which I will refer below.) Like members of the Peart‒Bate circle, Chapman was clearly well read in good poetry; her book records the work of such widely respected eighteenth-century authors as Elizabeth Carter, Charlotte Smith, James Beattie, John Langhorne, Thomas Percy, and Robert Burns. Again, little is known about Chapman except that she (and/or her suitor Scriblerus) had some connection to the Warminster area, since two of the volume’s poems are dated from there. Chapman does indicate magazines and anthologies as sources of some of her copied poems – one item, for example, is headed “A Winter-Piece (Elegant Extracts)” – but these are proportionately far fewer than those in the Oxford gentleman’s book, and the paucity of such references suggests they were not her primary source of reading material; sequences of poems by one writer, such as the opening group of Burns works, point rather to books.

Figure 7.2 Eliza Chapman, “Poetry, Selected & Original. 1788 & 1789,” frontispiece.

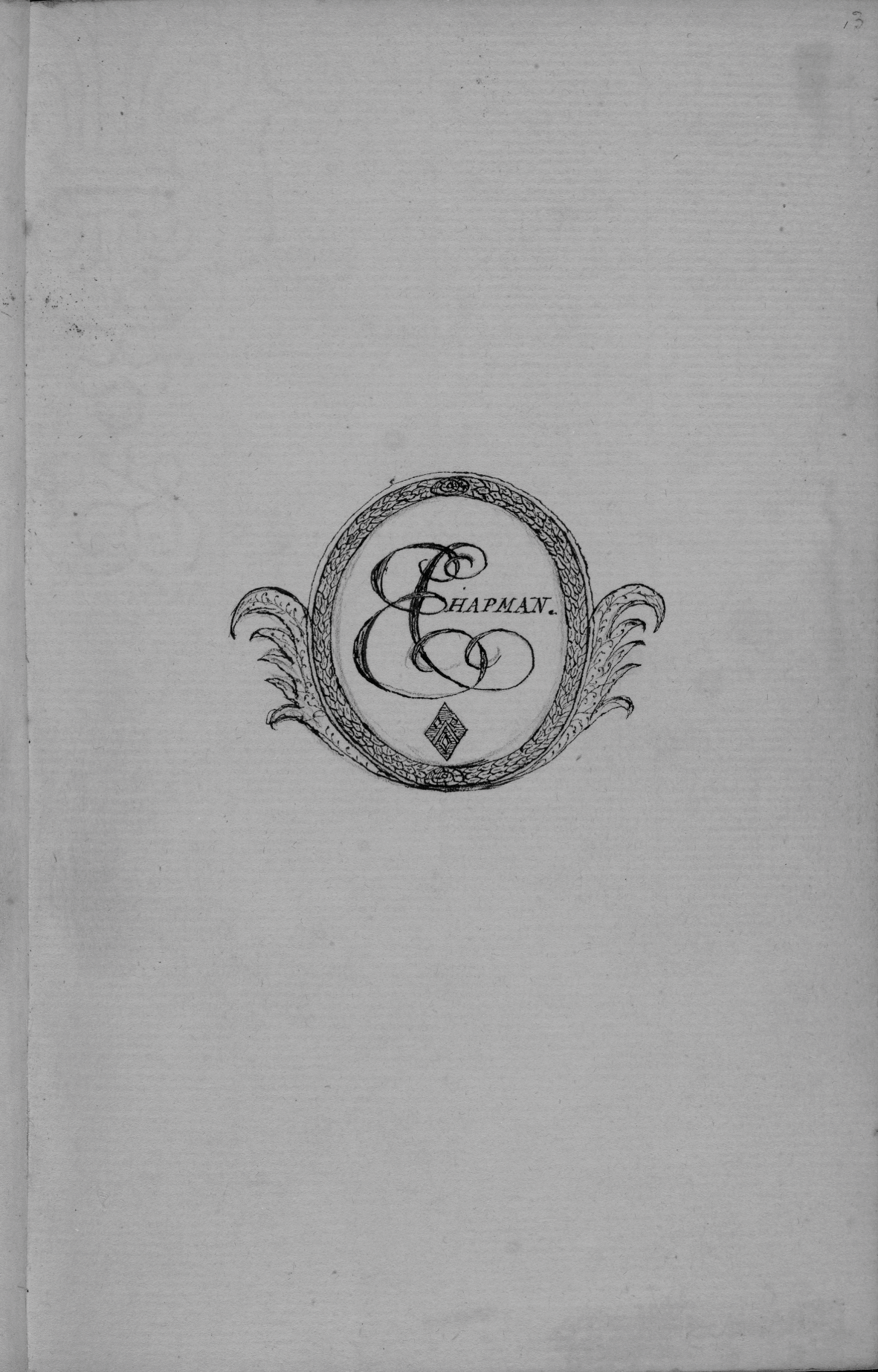

Balancing this “Poetry, Selected” is the “Poetry, … Original” of Chapman’s title: items of her own composition and those of “Scriblerus,” the man who may have become her husband at some point during or just after the compiling of the book. Scriblerus (or Scriblerus Secundus) is the most represented poet in its pages, notably in a series of tender and heartfelt poems addressed directly to “Eliza”: in the voices of her pet birds, in the guise of her portrait, and in poems written to her while she sleeps. Some of these poems appeal for their inventive whimsy, as does “To Eliza; From her favorite Robin Found in his Cage. Mar 1789,” in which her pet robin says he has long wished to express his gratitude to her for saving him from death and feeding him, and then concludes:

The poem is signed “ROBIN. Counter-sign’d Scriblerus Sec.”37 Nevertheless, an undercurrent of sadness and mystery runs through the sequence, in poems like the “Sonnet” depicted in Figure 7.2, as Scriblerus repeatedly complains of endless ills and the need to regulate his passions by reference to Eliza’s example of steady virtue. This may well be a lover’s poetic hyperbole, but the strain of unhappiness is echoed ominously by the two prefatory poems, dated 1790 and 1793 and both signed “T.E.T.,” which seem written to bolster Eliza’s courage in the face of a state of poverty and disenfranchisement. T.E.T. is addressed in the collection proper in a poem by “E.S.T.” dated January 4, 1789 – a birthday poem lamenting the sorrow that has engulfed them. In a book with such a small group of coterie contributors, it is plausible that E.S.T. is Eliza herself before her marriage, addressing a brother. This conjecture would be supported by an interpretation of Scriblerus’s headnote to a poem by Langhorne – “A Character/ By Dr. Langhorne/ Now addrest to E.C./ Whom it suits to a T.” – as a play on Eliza’s maiden name, if her married name is Chapman. Eliza herself, though she clearly cherished Scriblerus’s poems and proudly recorded her own name as the author of several occasional poems accompanying gifts to godchildren (see Figure 7.3), copies no poems from herself to Scriblerus into the book. Did she ultimately reject Scriblerus? Did he die shortly before or after their marriage? Did poverty prevent their union or make it unhappy?

Figure 7.3 From Eliza Chapman’s personal miscellany, “Sonnet” by Scriblerus, “Lines from Eliza to her God-daughter,” and “The Shakespeare Gallery,” by Scriblerus.

Given these unknowns, Eliza and Scriblerus’s tantalizing relationship is most clearly transmitted to us through the poetry they wrote, just as it is mediated for themselves by the poetry they exchange and discuss together. Thus, Burns’s song beginning “From thee, Eliza, I must go” struck an obvious chord. Scriblerus’s just-cited headnote to the Langhorne poem “A Character,” originally titled “To Mrs. Gillman,” is accompanied by an alteration of the poem’s tenth line to address “Eliza” rather than “Gillman.”38 Such affective messaging through poetry is founded upon a shared appreciation of both Burns and Langhorne, who feature prominently in the miscellany’s poetry selections. Other transactions are critical or educative: Scriblerus contributes a poem written at Warminster in August of 1788, inspired by Thomas Browne’s Religio Medici, and he adds explanatory notes to others, referencing The Spectator in relation to one of his own compositions and James Beattie’s Christianizing revisions as a note to The Hermit. Scriblerus’ poem “The Shakespeare Gallery” (Figure 7.3) combines references to Shakespeare plays with a celebration of the newly opened Boydell Shakespeare Gallery in London. Eliza Chapman’s book, then, reflects how coterie literary life might be conducted at the end of the 1780s in a kind of dialog with the poetry issuing from the press through both books and magazines and even with contemporary literary events. Informed and inspired by what is read, seen, and discussed, the coterie on a very private scale continues to produce and exchange original, handwritten poems as the medium best suited to express, enhance, and preserve both the momentous and the quotidian occurrences of domestic life.

At about the same time as Scriblerus’s voice fell silent – in May of 1790 – a woman by the name of “Mrs. C. W—ll” wrote a poem to another “Mrs. W—ll” beginning:

going on to imagine the ideal future qualities of the addressee’s two daughters. This poem, with its occasional title of “Verses Address’d To Mrs. W—ll by A Lady Mrs. C. W—ll May 20th 1790,” became the first in a series of eleven poems carefully copied into Brotherton manuscript Lt 100 at its “end” or “heart” – that is, almost halfway through its 119 numbered folios, but at the point where its first incarnation, begun at folio 1, meets its second, turned upside down and begun from the back of the volume, filling the blank pages in sequence from 119 v to 48. While entries in distinctly different hands are found scattered throughout the book, the bulk of its contents appear to have been copied in the same hand. Those items that are dated follow no clear chronological sequence, suggesting that many or all of the items, whether from printed or manuscript sources, were compiled at a time later than the recorded dates. (The latest date given is 1810, for an appearance in the York Chronicle of the poem “On the Death of Lord Collingwood,” who died in that year.) Many, however, stem from the late 1780s and the 1790s; the set of eleven poems identified as by Mrs. W—ll and her friends thus sits at the chronological, as well as the physical, center of the book.

As we read this cluster of eleven poems, a picture of the lady and her coterie begins to emerge. She is Mrs. C. Wyvill, as later uses of the name clarify, and the next poem, “Wrote by Miss G—ll upon reading the foregoing Verses,” tells us that she has been ill and is elderly, but that her two nieces, the “sweet Buds” described in the previous poem, will help to cheer her advancing years. Miss G—ll, in turn, is “unus’d to Sing,” but has taken up her pen to pay her debt for the previous poem. Mrs. C. Wyvill writes further poems to the family of her nieces: there is a 1794 poem “To be presented to Miss Wyvill the Day she compleats her sixth Year by her Aunt & Godmother,” and an undated set of verses “Addressd to the Revd. Mr. Wyvill on the Birth of his Son,” evidently a brother for the “lovely Sisters” and son to a man admirable for his “Sterling Patriotic fire,/(Free from Self interest).” Looking through the lens of the Wyvill set at the rest of the book, scattered poems begin to look as though they have a story to tell. Such cases include the lines headed “August 28. 1787 Miss G—ll” protesting the lowly name of Scrub for a horse; followed by “Verses in favor of Scrub” by “Dr. W—rs,” arguing that the “poor, forlorn, dispised” creature “bred up on Moors” be allowed to keep his humble name; and perhaps also that titled “On the Word Last By a lady,” preceded by an epigraph from Helen Maria Williams and sourced from The York Chronicle for December 31, 1790. The compiler seems to have been a longtime fan of the now-deceased David Garrick: surrounding these early entries is a series of items related to the actor and playwright, whether his satiric lines on the York assembly rooms, epilogues composed by him, or anecdotes from his career.40

But this is not all we learn about Mrs. C. Wyvill and the coterie of which she appears to have been the center or anchor. This was a circle that discussed important life questions. “By a Lady sent to Mrs C. W-y-ll. Is Sensibility Conducive to Happiness” resolves the issue at hand with the conclusion “Who feels too little is a fool;/ Who feels too much runs Mad,” but Mrs. C. Wyvill, in “Verses In Aswer [sic] to those On Sensibility,” challenges the Lady to determine further how the ideal point between extremes can be achieved; the solution is “This Rule then take, A Rule which ne’er can fail,/ Let Reason stear the Helm, when Passion blows the Gale.” Other poems in the set underscore the point with fanciful allegories on “Mr. Rule A Watchmaker & Mrs. Wright Mantuamaker” coming together to further each other’s ends, and on “A Watch Compared to Conscience.” Wit and humor are clearly appreciated, leading to the recording of an “Extempore The Cream of the Corporation” which reads,

The composer of these extempore lines may also be the writer of two quatrains on the same page, headed “From the Times February 17 – 1794 – On a Drunkard” and signed “L.F.H.” – at the very least, the placement of the newspaper item in the midst of the sequence of the group’s poems is an endorsement of the sentiment. Mrs. C. Wyvill, her brother and sister-in-law, Miss G—ll, a Lady, L.F.H., and perhaps even Dr. W—rs, then, carried out a scribal conversation in verse on a wide range of topics, from the earnest to the ridiculous, and someone considered the records of that conversation valuable enough to copy them into this book twenty years later.41

L.F.H.’s piece from The Times also makes it clear that, despite its manifestation in a distinct cluster of occasional poetry in the volume, the Wyvill coterie was not disengaged from the larger cultural context. In fact, the third entry in the eleven-poem set, immediately following the “Verses Address’d To Mrs. W—ll” and Miss G—ll’s response, is “To the Memory of Mr. Howard by Mrs. C. W-y-ll,” written in commemoration of John Howard, the Quaker prison reformer, who died in 1790. The poem begins with a timeworn gesture of feminine self-deprecation:

But the speaker is not shy to declare the “Ardent glow” for Howard’s “Vertues” that “throb[s] within [her] Heart,” nor to declare the Christlikeness of the reformer’s life. Although I have found no evidence that this poem was ever printed, its polish and public style of address clearly signal a degree of engagement with events of the day. In this context, even such seemingly passive gestures as copying materials from The York Chronicle, a frequent occurrence in Lt 100 in and around 1790, uphold Allan’s claim that in late Georgian commonplacing, public engagement was enacted through copying from such printed sources as newspapers: “by the later decades of the Georgian era … commonplacing, its functions further extended by its suitability for recording public events and allowing reflections upon them both in poetry and in prose, could help frame the intimate relationship between the reader as a private individual and the reader as a literate and engaged member of society.”42

Together, the late-century volumes of Eliza Chapman and of the Wyvill circle present evidence almost as strong as do the mid-century books of Mary Capell and Thomas Phillibrown, or the 1760s compilation of Eleanor Peart, for an active literary coterie. In all five collections, original poetry is composed and exchanged to commemorate private occasions and is treasured by members of the group. At the same time, each coterie is embedded in some way in its local community and in broader political events. While Phillibrown obviously had a close connection to several London periodicals in the 1740s and early 1750s, there does seem to be a clear shift in the latter decades of the century toward obtaining materials from a wide range of newspapers and magazines, as well as from anthologies and volumes of an individual author’s works, and toward documenting that fact. The Oxford gentleman’s book goes so far as to suggest that for some, embodied sociability has been displaced by print and the mediated sense of belonging it offers to the one who selects and compiles.

But for compilers such as the creator of Lt 100 recording the Wyvill coterie, print may have reinforced the long-term value assigned to the circulation of materials in script, by reviving the productions of hands like their own. Thus, we come across a pair of items from the York Chronicle for July 24,1794, responding to news of Robespierre’s Terror in France – one a “prophetic passage … taken from a [1778] letter written by the late Rev.d J W Flechere … (who was well known in Leeds)” predicting the imminent fall of popery under the Bourbons, and the other a pasted-in slip of paper, in the main compiler’s hand, containing a copy of a 1760 pastoral epistle addressed by Thomas Sherlock, Bishop of London, to the newly ascended George III, with the words: “The above extract from the Kentish Post of Decr 17, 1760, has been handed to us for insertion, on account of its particular application to the present period. It was lately found by a lady, enclosed in a morocco-wallet, among some family papers where it is supposed to have remained nearly from the time it is dated.”43 This is the same Bishop’s letter that Elizabeth Montagu circulated among her acquaintance thirty years earlier with strict instructions to lock it up in a cabinet (see Chapter 2). These letters’ histories and the print vehicle by which they are reintroduced into the public eye and from there re-enter a private compilation are emblematic of the continuous recirculation across porous boundaries that characterized the intermedial climate of the latter decades of the century. Moreover, the circumstantial presentation of these items’ origins suggests that the scribal hand of a well-known and respected local clergyman and the morocco wallet preserving a newspaper clipping among family papers are equally capable of bearing the coterie aura of exclusivity and privileged access – an aura that, like the cachet surrounding the gentleman’s manuscript travel narrative, only appears heightened at the close of the period of this study.