No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

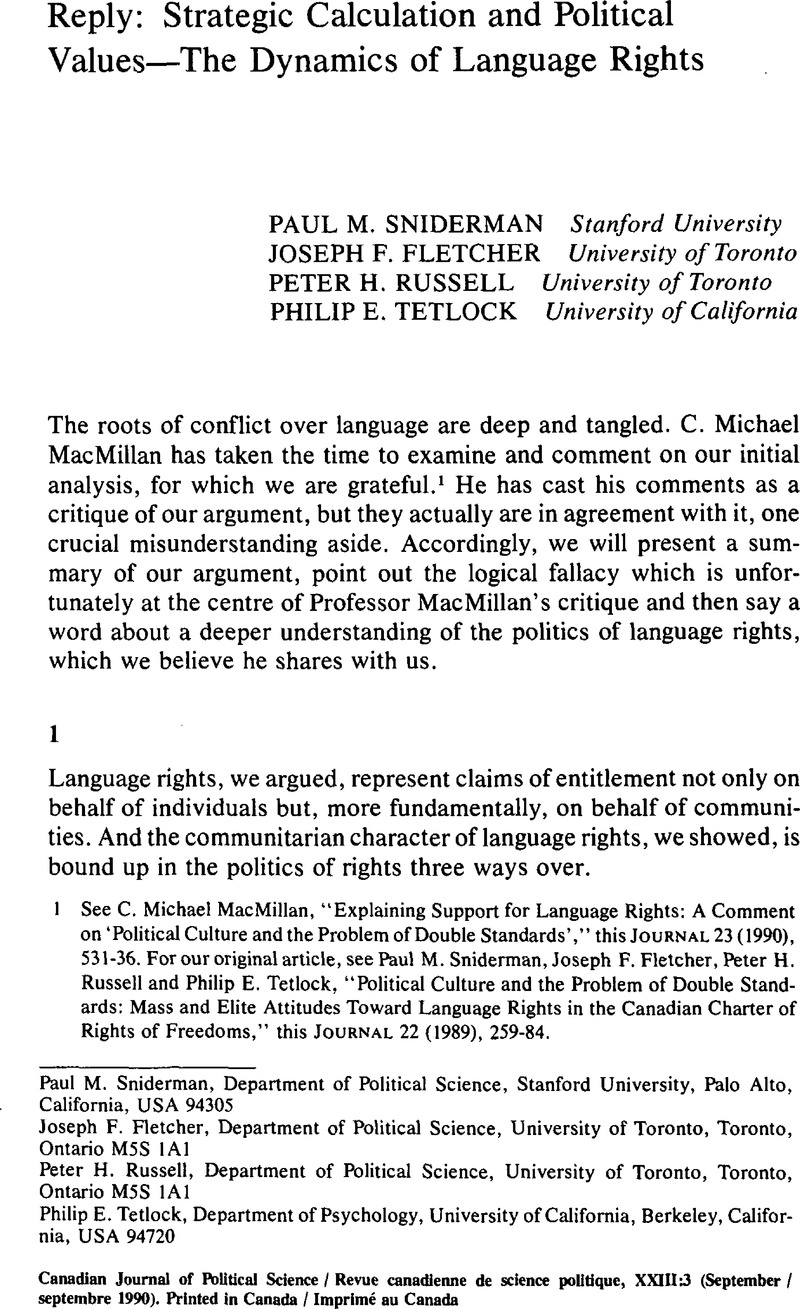

Reply: Strategic Calculation and Political Values—The Dynamics of Language Rights

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 November 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Comment/Commentaire

- Information

- Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique , Volume 23 , Issue 3 , September 1990 , pp. 537 - 544

- Copyright

- Copyright © Canadian Political Science Association (l'Association canadienne de science politique) and/et la Société québécoise de science politique 1990

References

1 See Macmillan, C. Michael, “Explaining Support for Language Rights: A Comment on ‘Political Culture and the Problem of Double Standards',” this Journal 23 (1990), 531–36.Google Scholar For our original article, see Sniderman, Paul M., Fletcher, Joseph F., Russell, Peter H. and Tetlock, Philip E., “Political Culture and the Problem of Double Standards: Mass and Elite Attitudes Toward Language Rights in the Canadian Charter of Rights of Freedoms,” this Journal 22 (1989), 259–84.Google Scholar

2 See Sniderman, Paul M., Tetlock, Philip E., Glaser, James M., Green, Donald Philip and Hout, Michael, “Principled Tolerance and the American Mass Public,” British Journal of Political Science 19 (1989), 25–46.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

3 See Frankfurt, Harry, The Importance of What We Care About (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

4 MacMillan, “Explaining Support for Language Rights, 534–35.

5 Ibid., 533–34.

6 On this point Professor MacMillan contends that our choice of mobility rights is an unfair one because “immigration and mobility rights are particularly sensitive issues in Quebec because they relate to the problem of protecting the viability of the French language” (Ibid., 536). But surely language education is at least as related to the viability of the French language as are issues of mobility. The difference between the issues of language and jobs is that the former explicitly concerns linguistic communi-ties while the latter involves provinces. Professor MacMillan is thus making a point for our argument. The only issue area where there is not a double standard on the part of francophones (or anglophones) is language rights, and this surely cannot be explained by introducing the untested, and ex post, claim that mobility issues trump language rights as emblematic of the French linguistic community.

7 The so-called Silence Index gauges support for the rights of people not to testify against themselves.

8 See Sniderman, Paul M., Fletcher, Joseph F., Russell, Peter H. and Tetlock, Philip E., “Liberty, Authority and Community: Civil Liberties and the Canadian Political Culture,” paper presented at the annual meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association, Windsor, 1988.Google Scholar

9 Macmillan, C. Michael, “Language Rights, Human Rights and Bill 101,” Queen's Quarterly 90 (1983), 357.Google Scholar

10 See Axelrod, Robert, The Evolution of Cooperation (New York: Basic Books, 1984).Google Scholar

11 This does not mean that anglophone support for French language rights evaporates completely, for it is based not only upon strategic calculation but also, as we showed, on underlying values including egalitarianism.