Charles Burney's published diary of his travels through Germany, the Netherlands and the United Provinces includes an account of his meeting in Vienna in September 1772 with the composer and keyboard player Georg Christoph Wagenseil. Having visited once already, on which occasion he heard Wagenseil play solo works at the keyboard ‘in a very spirited and masterly manner’, Burney returned to hear him again – this time with one of his students:

I went again this afternoon to Wagenseil's; he had with him a little girl, his scholar, about eleven or twelve years old, with whom he played duets upon two harpsichords, which had a very good effect. The child's performance was very neat and steady. M. Wagenseil was so kind as to promise, at my request, to get, if possible, some of his duets, and other new pieces, transcribed for me by Sunday, when I was to return to him again, to hear them accompanied by violins, and to take my leave.Footnote 1

The description of student and master at their respective keyboards is as enticing as it is vague. What pieces might Wagenseil and his student have played at two keyboards that could just as easily be ‘accompanied by violins’ on the following Sunday? While a small repertoire of compositions for two keyboards existed by 1775, when Burney's diary was published, most of these are so idiomatic that they defy the flexible instrumentation to which Burney alluded in this passage.

It is well known that some genres of chamber music in the eighteenth century were open to adaptation, either by composers or players, for various combinations of instruments, but the place of the two-keyboard configuration within these arrangement practices has not yet been understood.Footnote 2 The obscurity of this practice in the modern day may be due to the fragmentary evidence that survives: while some manuscript sources attest to the arrangement of chamber music for two keyboard instruments, the process of arrangement was often undertaken without any notated evidence, and it persisted as an unnotated performance practice through to the end of the eighteenth century. Trios were often arranged as keyboard duos, and the surviving manuscript evidence suggests that the organ trios of Johann Sebastian Bach, bwv525–530, were among the pieces most frequently played in this configuration.

My object in the present article is to reconstruct this practice and to situate it within larger musical contexts, relating it both to innovations in keyboard-instrument technology and to their underlying aesthetic motivations and cultural implications. Although keyboard-duo arrangements could be executed on two instruments of any type, I will present evidence that they were especially well suited to a ‘hybrid’ instrumentation – one that combines keyboard instruments with diverse mechanisms and timbres – since such a configuration allowed the players to capture some of the diversity of an ensemble of mixed instruments or, in the case of the organ trios of J. S. Bach, the mixed registration that was available on an organ. Instrument builders and theorists suggested that works for mixed ensembles could be rendered especially well on the combination keyboard instruments that were being invented and widely advertised, especially in German-speaking areas, during the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Such instruments fused the sounds and mechanisms of harpsichords, pianos,Footnote 3 organs and pantalons (a large double-stringed dulcimer), as well as providing bowing and dampening mechanisms and various other ‘stops’ (Veränderungen), all of which offered the possibility of a wide array of sounds within a single instrument. While few works in the keyboard-duo literature were designated explicitly for combination instruments or for harpsichord and piano together – the double concerto, Wq47, by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach is an important exception – I will show that arrangements of chamber music for keyboard duo were ideally suited to this hybrid instrumentation.

Burney and other writers suggested that keyboard duos were most at home within teacher–student relationships and within the family circle. On one level, these contexts may simply have aided the process of learning by example. More broadly, however, keyboard duos represent a distinctive manifestation of the ideal of ‘sympathy’ – an overarching social and aesthetic principle that saw individuals as united through mutual understanding, shared sentiment and common experience. To be sure, the expression of sympathy was a motivation in chamber repertories of the eighteenth century as a whole, but the keyboard-duo arrangements warrant consideration in light of this ideal because they cultivate both physical and emotional bonds between the players in a singular way: united in both bodily motions and musical sentiments, players of keyboard duos could rehearse the formation of sympathetic bonds even as they articulated their individual identities.

Beyond uncovering the historical evidence for the little-known performance practice of keyboard-duo arrangement, I also seek to revive it. The sources of evidence upon which I draw, therefore, include not only traditional historical materials such as notated musical manuscripts, instructions from composers, performance treatises and travel diaries, but also my own experience as a player of keyboard duos. In particular, the more ephemeral aspects of the practice – especially the ways in which its sounds and physical habitus result in the expression of shared sentiment and sympathy – come into focus through consideration of this experience. Although this approach depends on individual practice and personal taste, and is therefore variable, such variability was a feature of the keyboard duo in the eighteenth century as well. Performance partners could choose which pieces to arrange, what type of instrumentation and timbral combinations to use, and how to experience and conceptualize the effects of the resulting music-making, and these choices were integral components of the practice.

REPERTOIRE BEYOND NOTATION: ARRANGEMENTS FOR TWO KEYBOARDS

It is well known that instrumentation in chamber music of the eighteenth century was flexible; the term ‘arrangement’ can be misleading, since it suggests that there was one ‘ideal’ or ‘correct’ instrumentation for a given work. Often, in reality, performers simply played on the instruments that were available to them; composers, too, were willing to entertain numerous instrumentations for a given piece, with a single version seldom emerging as a definitive or authoritative one.Footnote 4 Such is the case, for example, with Johann Sebastian Bach's sonatas bwv1039 for two flutes and continuo and bwv1027 for viola da gamba and obbligato harpsichord, which are nearly identical aside from their instrumentation. Although the continuo sonata is thought to have been written first, there is no reason to see the viola da gamba version as less successful than or inferior to the original version.Footnote 5 Steven Zohn, among others, has remarked on the prevalence of this type of arrangement in Berlin around the middle of the eighteenth century; such arrangements survive for works by Johann Joachim Quantz, Carl Heinrich Graun, Johann Gottlieb Graun and others associated with the court of Frederick the Great. Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach likewise adapted numerous trios by assigning one of the soprano lines to the right hand of the keyboard while the left hand of the keyboard plays the bass line; chordal accompaniment is employed only when the right-hand line is resting, and the other soprano line remains for a single obbligato instrument.Footnote 6

In addition to this commonly recognized practice of arrangement, surviving evidence attests to a different sort of arrangement of the trio: from two treble instruments with continuo to two keyboard instruments. In this disposition, one of the treble lines is assigned to the right hand of one keyboard player, the other treble line to the right hand of the other player and the bass line to both left hands in unison. This practice dated at least as far back as the 1720s, when Couperin described it in the introduction to his Apothéose de Lully:

Ce Trio, ainsi que l'Apothéose de Corelli; & le livre complet de Trios que j'espere donner au mois de Juillet prochain, peuvent s'exécuter à deux Clavecins, ainsi que sur tous autres instrumens. Je les exécute dans ma famille; & avec mes éléves, avec une réüssite tres heureuse, sçavoir, en joüant le premier dessus, & la Basse sur un des Clavecins: & le Second, avec la même Basse sur un autre à l'unisson: La Verité est que cela engage à avoir deux exemplaires, au lieu d'un; & deux Clavecins aussi. Mais, je trouve d'ailleurs qu'il est souvent plus aisé de rassembler ces deux instrumens, que quatre personnes, faisant leur profession de la Musique.Footnote 7

This trio, as well as the Apothéose de Corelli, and the complete book of trios that I hope to publish next July, may be executed on two harpsichords, as well as all other types of instruments. I play them [on two harpsichords] with my family and with my students, with a very good result, by playing the first soprano line and the bass line on one of the harpsichords, and the second [soprano line], with the same bass line, on another at the unison. The truth is that this requires having two copies [of the score] instead of one, and two harpsichords as well. But I find that it is often easier to assemble these two instruments than four separate professional musicians.

That Couperin situated this performance practice within domestic and educational settings – writing that he played the trios as two-keyboard arrangements with his students and his family members – is significant, as it points to the two general categories of musicians who applied the performance practice that he described. First were professional musicians as well as their family members and students, both of whom may likewise have been in training as professional musicians. The Bach family apparently employed keyboard duos for the same purposes that Couperin did: for the sake of professional musical education within the context of the family. Reports originating with Wilhelm Friedemann Bach indicate that Johann Sebastian's concertos for two and three keyboards were written for performance by the composer and his sons.Footnote 8 Sebastian helped to prepare the parts for Friedemann's concerto for two keyboards without orchestra, Fk10, and perhaps played it with him as well.Footnote 9 Although Burney was less specific about the musical performance practices than Couperin, his description of the music-making by Wagenseil and his student indicates that playing a work originally scored for keyboard and violins on two keyboard instruments was a component of her musical education.

The other category of musicians who played keyboard-duo arrangements was amateur players wealthy enough to own two keyboard instruments; this latter group, as I will show, is attested to by manuscript evidence from the Dresden electoral court as well as the collections of the Berlin patron and keyboard player Sara Levy and her family – a group that also maintained the tradition of playing double concertos and keyboard duos seen in the Bach family. Most of the documentation for the practice of keyboard-duo arrangements emerges from German-speaking lands, where the French influence on keyboard music was especially strong, but the limited surviving evidence should not be taken to mean that the practice itself was so limited. The incomplete record of this performance practice means that we may never know precisely how widespread it was. Indeed, wherever compositions for two keyboards were found, such arrangement practices were also likely to have been used – for example, in Vienna, where Mozart's sonata for two keyboards, k448, was published posthumously by Artaria in 1795, and in Paris, where published compositions for keyboard duo by Jean-François Tapray and Henri-Joseph Rigel, and manuscripts of works by the salon hostess Anne Louise Boyvin d'Hardancourt Brillon de Jouy, likewise point at usage of two keyboard instruments in cultivated musical and social circles.Footnote 10 The familial and pedagogical contexts for the usage of keyboard-duo arrangements are important for understanding their social and aesthetic function. Beyond the obvious technical modelling involved in this practice, in which a teacher would present appropriate keyboard technique for imitation by the student, the shared musical experience of keyboard duos points, as noted earlier, to the cultivation of sympathetic sentiments and emotional communication.

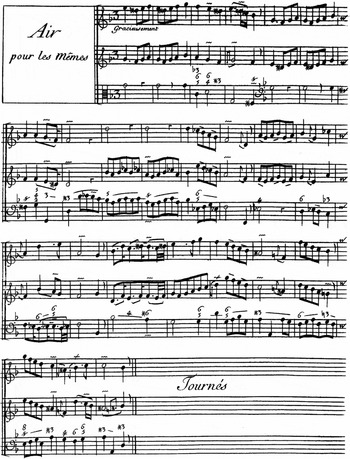

Another significant point that emerges from Couperin's description of arrangements for keyboard duo in the Apothéose de Lully is that, although two exemplars of the original score would be required, the transfer from the trio instrumentation to the medium of the keyboard duo did not require the production of separate partbooks. The two keyboard players would have been able to read from the trio score, extracting the bass line and the relevant soprano line from the trio texture (see Figure 1). Indeed, Couperin's inclusion of this recommendation in a published work suggests that he saw this process as simple enough to be undertaken by amateur players. Thus, as he explained, the adaptation from a trio to a duo for two keyboards could have been done without a trace of notated evidence. By extension, I would argue, although there are relatively few notated arrangements of trios for two keyboards that survive from the eighteenth century, the practice was more common than has previously been thought. New written materials were not necessary in order to make the transfer of instrumentation possible.

Figure 1 François Couperin, ‘Air pour les Mêmes’, from Concert instrumental sous le titre d'Apothéose composé à la mémoire immortelle de l'incomparable Monsieur de Lully (Paris: author and Le Sieur Boivin, 1725; facsimile edition, New York: Performers’ Facsimiles, 2001), first section. Used by permission of Broude Brothers Limited

Nevertheless, the type of arrangement that Couperin describes as an unnotated tradition is in fact confirmed by some notated evidence. Indeed, the production and preservation of manuscripts in this configuration suggest that keyboard-duo arrangement of trios continued until around 1800. Even for works that were first composed in the early or mid-eighteenth century, manuscript copies made for performance on two keyboards most often date to decades later – that is, to the latter half of the century. Such is evidently the case with the arrangements for two keyboards of Handel's trios hwv386a, 387, 388, 389, 390a and 391, held in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin,Footnote 11 as well as the arrangement of the Sonata in C major b:XV:53 by Carl Heinrich Graun, now preserved at the National Library of Sweden.Footnote 12 Current music was also sometimes transferred almost immediately upon publication to this medium; surviving manuscripts in this configuration include trios by Baldenecker, C. E. Graf, Tommaso Giordani, Ignaz Pleyel and dozens of others. As the obbligato keyboard trio began to rise in popularity, such works were also adapted to the keyboard-duo configuration, with one player executing the obbligato keyboard part and the other playing the violin and cello ‘accompaniments’ on a single keyboard.Footnote 13 A related phenomenon, affirmed by some manuscript collections, is the arrangement for two keyboards of solo concertos, in which one keyboard takes the part of the soloist while the other plays the part of the orchestra. While this ‘genre’ of arrangement may be understood from a modern perspective as distinct from arrangements of chamber music, it seems possible that such generic distinctions were not as clearly drawn in the eighteenth century.Footnote 14 The significance of the manuscript arrangements of all these types lies first and foremost in their preservation of the practice of arrangement for keyboard duo; the music itself is, in most cases, essentially unchanged from that found in the original instrumentation.

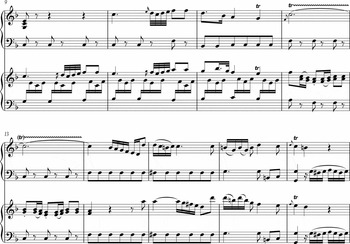

Among the most significant sources attesting the persistence of the keyboard-duo medium for the performance of trios in the late eighteenth century, as Couperin described, are partbooks of the organ trios by J. S. Bach, bwv525–530, which survive in numerous manuscripts.Footnote 15 As with the arrangement of trios for obbligato keyboard and melody instrument, the arrangement of the organ trios for two keyboards was apparently a practice most prominent in Berlin: two of these sets of partbooks are associated with the Baron van Swieten, who is known to have been a key figure in the importation of the Bach tradition from Berlin to Vienna.Footnote 16 Another of these sources, also brought from Berlin to Vienna, survived in the collection of Fanny von Arnstein, sister to Sara Levy. Levy's own collection included a copy of the organ trios in full score, suggesting that she may have read from the score at one keyboard while her sister read from a partbook at another.Footnote 17 The method behind the arrangement is identical to the one described by Couperin (see Figures 2a and 2b).

Figure 2a Opening page of the keyboard-duo arrangement of J. S. Bach, Organ Trio Sonata bwv525/i, Primo partbook. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, A-Wn Mus.Hs.5008. Used by permission of Bärenreiter Verlag

Figure 2b Opening page of the keyboard-duo arrangement of J. S. Bach, Organ Trio Sonata bwv525/i, Secondo partbook. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, A-Wn Mus.Hs.5008. Used by permission of Bärenreiter Verlag

Given Couperin's suggestion that the transfer from trio-sonata scoring to keyboard-duo scoring would have been done tacitly, it seems curious that copyists and collectors should turn, in the second half of the eighteenth century, to producing manuscript copies of partbooks for two keyboards. The motivations for the production of these manuscripts must remain a matter of speculation. One possibility is that collectors seeking to acquire copies of such pieces knew that they were more likely to play them on two keyboards than in the trio-sonata disposition, so the production of partbooks reflecting keyboard-duo arrangements was more efficient than the production of scores. This is true especially for the organ works, since organs with pedals (or pedal additions to harpsichords or pianos) were less likely to be found in domestic settings than were harpsichords, pianos and other keyboard instruments without pedals. In certain cases, however, there was something unusual or special about the two-keyboard arrangements that made their preservation in notation especially desirable. I turn now to a series of examples that demonstrate the range and types of changes that composers or arrangers made to render chamber works more suitable for a keyboard-duo setting.

For the Sonata Wq87 of C. P. E. Bach, originally for flute and obbligato harpsichord, the complete partbooks for two keyboard players do not survive; instead, what remains is just a single manuscript page of instructions for the creation of the keyboard-duo arrangement.Footnote 18 Most of the changes that the composer mandated involve the alteration of long notes, which can be sustained expressively on the flute, to a more fully worked-out keyboard part that keeps the harmony sounding through idiomatic figuration. The result is an integrated dialogue in these places between the two players’ right hands (Examples 1a and 1b). In keeping with the idea of keyboard-duo arrangements as a mode of playing suited to students and teachers, we might speculate that Philipp Emanuel produced his instructions for this arrangement for a student copyist who was to produce the new arrangement. Perhaps such idiomatic alterations would normally have been improvised or worked out in lessons; here, the composer seems to have wanted to prescribe them more closely.

Example 1a Carl Philip Emanuel Bach, Sonata Wq87/i, bars 15–22, in the original scoring (Carl Philip Emanuel Bach: The Complete Works, series 2, volume 3.2, Keyboard Trios II, ed. Steven Zohn, with Appendix ed. Laura Buch (Los Altos: Packard Humanities Institute, 2010))

Example 1b Carl Philip Emanuel Bach, Sonata Wq87/i, bars 15–22, in the keyboard-duo arrangement (Keyboard Trios II, ed. Steven Zohn, with Appendix ed. Laura Buch). The Appendix is an arrangement by Buch of Wq87, and the instructions for making the keyboard-duo arrangement are given in F-Pn W.3 (7)

In keyboard-duo arrangements of other types of chamber works, the arrangement was a more complex process that required careful planning – thus the production of a manuscript reflecting the disposition of voices and their division between the two keyboards. One such case is a manuscript transmitting a keyboard-duo version of the Op. 11 quintets of Johann Christian Bach, which deviates in numerous ways from the published chamber version.Footnote 19 Examples from the first quintet of the set elucidate the kinds of changes that the anonymous arranger made. The arrangement begins in the same manner as most two-keyboard arrangements of trios: with both keyboard players performing identical bass lines, and the two right hands playing one line each of the higher instruments – in this case, the second (oboe) and fourth (viola) parts from the top (Examples 2a and 2b). As the texture thickens, however, and the other two treble instruments become integrated into the work, the arranger adopted a different method: in some passages the bass line drops out of one of the keyboard parts, so that the two instruments assume different roles within the texture (Examples 3a and 3b).

Example 2a Johann Christian Bach, Quintet Op. 11 No. 1, Allegretto, bars 1–18, in the original scoring. Six quintetto a flute, hautbois, violon, taille, & basse (Amsterdam: J. J. Hummel, ?1784)

Example 2b Johann Christian Bach, Quintet Op. 11 No. 1, Allegretto, bars 1–18, in the keyboard-duo arrangement. D-Dl Mus. 3374-Q-7

Example 3a Johann Christian Bach, Quintet Op. 11 No. 1, Allegretto, bars 84–103 in the original scoring

Example 3b Johann Christian Bach, Quintet Op. 11 No. 1, Allegretto, bars 84–103 in the keyboard-duo arrangement

The Andantino middle movement of this quintet begins with only the cembalo primo part playing the bass line and the accompanimental figures, as the secondo takes the long notes in the flute and oboe parts of the original version without anything in the bass register; later in the movement, the original scoring reverses these roles, with the winds taking accompanying motifs while the violin and viola play the expressive melodies with long notes. For the long notes in these passages, the two keyboards would need to find ways of continuing the sound of these notes so that they would not simply die away; added trills or other essential ornaments would be possible, and indeed, in the cembalo primo part at bar 12 and bar 35, the arranger has added a trill not found in the original viola part (see Examples 4a and 4b). The absence of notated trills on other long notes does not of course preclude their addition in performance. Indeed, the added trills shown in Examples 4a and 4b hint at the largely unnotated practice of ornamentation required for performance on two keyboards. C. P. E. Bach's instructions for the two-keyboard arrangement of Wq87 also offer the possibility of more florid figuration idiomatic to the keyboard. In addition, the arrangement of the J. C. Bach quintet introduces an Alberti bass part in one section to replace the original figuration (see bars 9–11 of Example 4b), which is more idiomatic to string instruments.

Example 4a Johann Christian Bach, Quintet Op. 11 No. 1, Andantino, bars 9–17, in the original scoring

Example 4b Johann Christian Bach, Quintet Op. 11 No. 1, Andantino, bars 9–17, in the keyboard-duo arrangement

One manuscript, now held at Harvard University, suggests that even more dramatic changes were possible. The interior title-page, in the hand of Johann Nikolaus Forkel, indicates that what follows is a ‘Sonata a dui [sic] cembali overo flauti, composta da Guiglielmo Friedemanno Bach’. In fact, the piece in question is Friedemann's F major duet for two unaccompanied flutes, Fk57. The intention – either on the part of Forkel or that of the copyist – must have been for a bass line to be added to this piece so that it could be performed as a keyboard duo, with the two right hands of the keyboard players each taking one of the flute parts, and the left hands playing a bass line together. Instead, however, the third staff is left blank; evidently the planned bass line was never composed (see Figure 3).Footnote 20 The significance of this manuscript increases in light of Forkel's assessment, in his biography of J. S. Bach, of the works for unaccompanied violin and cello:

Wie weit Bachs Nachdenken und Scharfsinn in der Behandlung der Melodie und Harmonie ging, wie sehr er geneigt war, alle Möglichkeiten in beyden zu erschöpfen, beweiset auch sein Versuch, eine einzige Melodie so einzurichten, daß keine zweyte singbare Stimme dagegen gesetzt werden konnte. Mann machte sich in jener Zeit zur Regel, daß jede Vereinigung von Stimmen ein Ganzes Machen, und die zur vollständigen Angabe des Inhalts nothwendigen Töne so erschöpfen müsse, daß nirgends ein Mangel fühlbar sey, wodurch die Beyfügung noch einer Stimme etwa möglich werden könnte. Man hatte diese Regel bis auf Bachs Zeit bloß auf den 2–3 und 4stimmigen Satz, und zwar überall noch sehr mangelhaft angewendet. Er that dieser Regel nicht nur in 2–3 und 4 stimmigen Satz volle Genüge, sondern versuchte auch, sie auf den einstimmigen Satz auszudehnen. Diesem Versuch haben wir 6 Soli für die Violine und 6 andere für das Violoncell zu verdanken, die ohne alle Begleitung sind, und durchaus keine zweyte singbare Stimme zulassen. Durch besondere Wendungen der Melodie hat er die zur Vollständigkeit der Modulation erforderlichen Töne so in einer einzigen Stimme vereinigt, daß eine zweyte weder nöthig noch möglich ist.

In order to realise the care and skill Bach expended on his melody and harmony, and how he put the very best of his genius into his work, I need only instance his efforts to construct a composition incapable of being harmonised with another melodic part. In his day it was regarded as imperative to perfect the harmonic structure of part-writing. Consequently the composer was careful to complete his chords and leave no door open for another part. So far the rule had been followed more or less closely in music for two, three, and four parts, and Bach observed it in such cases. But he applied it also to compositions consisting of a single part, and to a deliberate experiment in this form we owe the six Violin and the six Violoncello Solo Suites, which have no accompaniment and do not require one. So remarkable is Bach's skill that the solo instrument actually produces all the notes required for complete harmony, rendering a second part unnecessary and even impossible.Footnote 21

Figure 3 Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, IV Sonaten für ein und zwei Klaviere, first page. Houghton Library, Harvard University, MS Mus 62.6

In the flute duet, Friedemann Bach continued the tradition of Sebastian and his contemporaries of composition for treble instruments without bass accompaniment. Forkel's biography of the elder Bach viewed such works as independent and complete, leaving ‘no door open for another part’. In the case of Friedemann's flute duet, it seems that either Forkel or the copyist imagined that a bass line could be added that would enhance the work, rendering it usable in a keyboard-duo arrangement, and in this sense it contrasts with the unaccompanied violin and cello works of J. S. Bach – though in the subsequent generation, Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Robert Schumann indeed saw fit to add their own accompaniments to Sebastian's solo string music.Footnote 22 It is unclear why the planned bass line was never added to the W. F. Bach duet. The rhythmic profile of the two flute lines is quite active, and for that reason it seems possible that the arranger – again, we might speculate that it was one of Friedemann's students, or another student in Forkel's circle – who was meant to undertake the addition of the bass line found it unsuitable after all. However, it seems noteworthy that, at least initially, someone deemed it possible for the work to be adapted to include the extra line: even the boundary between duo and trio was permeable. The fluidity of genre and instrumentation implied by this manuscript, with its designation for either flutes or keyboard duo, confirms the flexibility in approach to keyboard duos shown in other sources. It is worth mentioning, too, that the layout of this source is identical to that of Couperin's trios in the Apothéose de Lully and the scores of the Bach organ trios, with both treble lines and the imagined bass line appearing in a single score. This layout suggests again that two-keyboard arrangements were often played in a manner that appeared at odds with their notation.

COMBINATION INSTRUMENTS FOR TWO PLAYERS: KEYBOARD DUOS AND THE PURSUIT OF VARIETY

As a rule, keyboard-duo arrangements from the mid- to late eighteenth century do not designate specific instruments. Most often the partbooks are labelled ‘cembalo I’ and ‘cembalo II’, or ‘Clavier I’ and ‘Clavier II’; both of these terms could refer generically to any stringed keyboard instrument.Footnote 23 Moreover, these designations do not preclude the use of keyboard instruments of different types, and indeed, in the pages that follow I will show that a hybrid instrumentation, juxtaposing, for example, the sounds of the piano and the harpsichord, was an option that increased the expressive potential of the arrangements.

Recent work with the surviving instruments and documentary evidence from the second half of the eighteenth century has shown that the piano, harpsichord, clavichord, pantalon and other keyboard types experienced a ‘happy coexistence’ throughout much of the eighteenth century.Footnote 24 As new inventions were introduced, they were folded into the already diverse keyboard culture, expanding the palette of sounds available to the player, and many inventors developed ways of combining distinct mechanisms within a single instrument.Footnote 25 Such instruments should be understood within the culture of invention and experimentation that led, during the same period, to the development of musical automata, orchestrions, the glass harmonica, musical clocks and so forth.Footnote 26 Like these other instruments, combination keyboards attest to the concern with diversity of sound – a diversity for which modern terminology cannot fully account.Footnote 27 As Michael Latcham has argued, the tendency among modern observers to place these instruments into the clear-cut categories of harpsichord or piano runs the risk of ‘[stripping] the instruments of some of the possibilities they possess’.Footnote 28 Instead, as Latcham has noted, ‘combination instruments put at the command of a single player a variety of sounds, satisfying at a time when the idea of variety in unity, the microcosmic reflection of a varied universe under the seeing eye of a single deity, was still attractive’.Footnote 29

In this context, Emily I. Dolan's recent explorations of the idea of timbre in the late eighteenth century are of primary importance. Examining the orchestral music of Haydn, Dolan has demonstrated that the composer deployed specific orchestral gestures and timbral topoi to convey meaning within his works. Citing examples of the numerous keyboard instruments, both invented and imagined, available to the late eighteenth-century mind and ear, Dolan has noted that keyboard instruments were thought to encompass potentially all of the sounds of the orchestra. As Christian Friedrich Schubart exclaimed in his Ideen zu einer Ästhetik der Tonkunst, published in 1806, ‘Ja ein Edelmann in Mainz hat eins verfertiget, wo die Flöte, Geige, das Fagott, die Hoboe, ja sogar die Hörner und Trompeten, ins Fortepiano gezaubert wurden. Wenn das Geheimniss des Baues von diesem grossen Erfinder der Welt kund gethan wird; so hat man ein Instrument, das alle andern verschlingt’. (A nobleman in Mainz has made one where the flute, violin, bassoon, oboe, even horns and trumpets were conjured up in the fortepiano. If the secret of the construction is made known by this great inventor to the world, one will have an instrument that devours all others.)Footnote 30 Yet in contrast to the orchestral music of Haydn, in which timbres prescribed by the composer play a role in the expression of musical meaning, within the world of the keyboard, the choice of instrumentation was often left to the discretion of the performer. Combination instruments juxtapose or fuse the sounds of different keyboard mechanisms and alter those sounds through Veränderungen – stops, analogous to organ stops – that would dampen or extend the resonance of the instrument, increase or decrease its dynamic level and provide novel effects to capture the interest and imagination of the listener.

The keyboard-duo medium was very much at home within this culture of invention. Performance at two keyboards was common enough in 1768 to warrant special mention in Jakob Adlung's monumental treatise on organ building, the Musica mechanica organoedi. In his chapter on stringed keyboard instruments, Adlung provided a diagram of a harpsichord designed for two-keyboard repertoire (Figure 4), explaining it as follows:

Man kann auch ein Clavicymbel-Corpus mit zwey Clavieren machen, damit ihrer zwey spielen können. Man macht nämlich die Länge gewöhnlicher maaßen, ohne daß man etwann 1’ oder etwas weniger drüber nimmt. Aber die Breite wird durchaus überein in forma quadrati oblongi. Alsdann macht man auch die Decke durchaus; doch wird oben darüber ein Unterschied gemacht von einer Ecke zur andern von a nach b, etwann also: [Figure 4]. So präsentirt dieß ein doppelt Claveßin, deren das eine das Clavier von a nach c hat; das andere aber von d nach b. Das übrige wird gemacht, wie bisher gesagt worden.

It is also possible to build a harpsichord case with two keyboards, so that the two of them can play together. An instrument of normal length is built, or perhaps a foot or so longer. But its width is constant, thus forming a rectangle. A soundboard is placed across the entire [instrument], but a divider is built on top of it from corner a to corner b. . . . This then forms a double harpsichord, one of whose keyboards extends from a to c and the other from d to b. Everything else is built as described above.Footnote 31

Figure 4 Diagram of the layout of a double harpsichord, in Jakob Adlung, Musica mechanica organoedi (Berlin: Friedrich Wilhelm Birnstiel, 1768; facsimile edition, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1961), 109

If Adlung's diagram seems rudimentary, real instruments that fit this type warranted repeated description in advertisements and essays in periodicals and dictionaries of the age. An advertisement in the Coburger Wöchentliche Anzeige boasted that

Der Orgel und Instrumentenmacher Herr Hofmann zu Gotha, hat ein neues Instrument erfunden, das aus einem doppelten Clavecin bestehet. Es hat auf jeder Seite zwey Claviere, und doch können alle 4 Claviere gekoppelt und von einer Person gespielt werden. Es können auch 2 Personen zugleich spielen, so daß man Stücke für 2 Claviere gesetzt, darauf herausbringen kann. Uebrigens ist es, wenn gleich alle 4 Claviere gekoppelt sind, nicht schwerer im Griff, als ein gewöhnliches Clavecin.Footnote 32

The organ and instrument-maker Herr Hofmann in Gotha has invented a new instrument, which consists of a double harpsichord. It has two keyboards on each side, and all four keyboards can be coupled and played by a single person. It can also be played by two people, so that one can perform works for two keyboards on it. Furthermore, when all four keyboards are coupled, the action is no harder to play than on a normal harpsichord.

Double harpsichords of the type built by Hofmann were only the beginning: in addition, numerous combination instruments could accommodate two players. Latcham has described combination instruments dating to as early as 1716; these persisted in the 1730s and 40s, but a flurry of inventions of combination keyboard instruments occurred in the 1770s to 90s.Footnote 33 One noteworthy example is the ‘mechanischer Clavierflügel’ of P. J. Milchmeyer, capable of producing as many as 250 sounds through the combination of stops and activation of different keyboards.Footnote 34 An extended description of this instrument, penned by the builder himself, appeared in Carl Friedrich Cramer's Magazin der Musik of 1783, and it made special mention of the suitability of the instrument for two players:

Dieser Flügel hat noch eine Schönheit, an welche noch nie von keinem Instrumentenmacher ist gedacht worden, das untere Clavier oder Pantalon schiebt sich heraus: es können zu gleicher Zeit zwey Personen auf einmal spielen.Footnote 35

This Flügel has yet another beautiful feature, which no other instrument maker has yet thought of: the bottommost keyboard (a pantalon) can be pushed out, [so that] two people can play it at the same time.

While no exemplars of Milchmeyer's instrument survive, another important and widely celebrated combination instrument for two players offers a window onto the aesthetic environment in which Milchmeyer operated. This was the so-called vis à vis of Johann Andreas Stein, a rectangular double-keyboard instrument with nested bent sides, as also shown in Adlung's diagram. One side of the vis à vis activated a harpsichord mechanism while the other activated a piano, and the two could be coupled so that the harpsichord and piano sounds could be combined for performance by a single player. As Latcham has noted, the surviving instruments suggest that Stein initially planned the vis à vis as a double harpsichord, but he altered his plans to create a combination harpsichord-piano.Footnote 36 This point underscores the close relationship between the two categories of instruments, and also the novelty of such inventions, which were constantly evolving. Describing the same instrument, an essay in the Musikalische Real-Zeitung of 1790 exclaimed that Stein ‘gehöret überhaupt unter die Genies, die immer auf die Vervollkommung arbeiten und denen es das größte Vergnügen ist, etwas Gutes und Schönes gemacht zu haben, gesezt auch, daß ihnen ihre Mühe nicht nach Verdiensten belohnt würde’ (belongs altogether among those geniuses who work always toward perfection and take the greatest pleasure in having made something good and beautiful, even though the pains that they take are not rewarded as they deserve to be).Footnote 37

A description of Stein's poli-toni-Clavichord, first mentioned in 1769, provides a fascinating account of the ways in which the sounds of the harpsichord and piano were thought to complement each other:

Gibt . . . das Forte Piano Instrument dem Flügel zugleich das Crescendo und Decrescendo auf die angenehmste Art mittheilet, so daß man nicht anders glaubt, als daß der Flügel selbsten diese Eigenschaft habe, da es doch blos vom Ersten herkommt. Der Flügel hingegen gibt dem Forte-Piano-Instrument, wenn es ohngedämpft gespielt wird, eine sanfte affectuose Annehmlichkeit, und reißt jenen gleichsam von einer Stuffe der Affecten zur andern, in fremden Ton-Arten mit fort, ohne das Ohr zu beleidigen.

The Forte Piano imparts to the harpsichord a most agreeable Crescendo and Decrescendo such that one believes that the harpsichord possesses this quality of itself, even though it actually originates in the Forte Piano. At the same time the harpsichord gives the Forte-Piano-Instrument, when played without the dampers, a soft pleasantness, swirling from one level of the affects to another, even in distant keys, without upsetting the ear.Footnote 38

In this description, the harpsichord and piano components of the instrument each provide an advantage that would not otherwise be available. Such relative advantages were noted by other musicians and critics throughout the second half of the eighteenth century. C. P. E. Bach, in his Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen, noted the positive qualities of all types of keyboard instruments, and he owned various sorts upon his death. He favoured the harpsichords of his day for the rhythmic impulse and clear articulations that they could provide in accompanying recitatives.Footnote 39 Latcham has shown that at the court of Frederick the Great, where Bach was employed until 1768, harpsichords were used at the opera and in large concert halls;Footnote 40 likewise, Adlung advocated the harpsichord over the piano for large ensembles and recommended the piano for chamber music only.Footnote 41 Yet Philipp Emanuel had a special preference for clavichords and pianos; as Burney reported, Bach ‘declares that of all his works those for the clavichord or piano forte are the chief in which he has indulged his own feelings and ideas’.Footnote 42 In free fantasias, Bach wrote, ‘the undamped register of the pianoforte is the most pleasing and, once the performer learns to observe the necessary precautions in the face of its reverberations, the most delightful for improvisation’.Footnote 43

Other writers in the latter part of the eighteenth century, too, recommended different sorts of keyboard instruments for various purposes and effects. The harpsichords of Späth had ‘many advantages, in particular their silvery, majestic sound and . . . accuracy’.Footnote 44 The builder Andreas Streicher, son-in-law to Johann Andreas Stein, described the piano as ‘[resembling] the sound of the best wind instruments’, noting in particular that its high register had a flute-like quality.Footnote 45 This characterization was later echoed by Hummel, while other writers, including C. P. E. Bach, emphasized the relationship between the sound of the piano and that of the human voice.Footnote 46

Laurence Libin has observed that ‘builders and buyers took such hybrids seriously throughout the century, though no music known today specifically requires their resources’.Footnote 47 However, I argue that the surviving instruments were ideally suited to the keyboard-duo repertoire, and to arrangements in particular.Footnote 48 The clearest connection between the two-player combination instruments and the process of arrangement is presented in Milchmeyer's description of his mechanischer Clavierflügel. After noting that the bottommost keyboard could be pushed out to accommodate a second player, Milchmeyer continued,

es können zu gleicher Zeit zwey Personen auf einmal spielen, welches bey den Duos einen ausserordentilichen schönen Effect macht; auch können hierbey mehrere Veränderungen gebraucht werden, denn unter der Zeit, daß der eine auf dem Flügel, Harfe, Flöte und Fagotte spielt, so accompagnirt der Andere die Partie der Violin auf dem Pantalon oder Laute; das Merkwürdigste von allem aber ist, daß Flügel und Pantalon zu gleicher Zeit können gespielt werden. . . . und es wegen der Stärke und Verschiedenheit der Instrumente einem kleinen Orchester vollkommen ähnlich [ist].Footnote 49

two people can play on the instrument at once, which creates an exceptionally beautiful effect in duos. Also, in this way, more Veränderungen can be used, since at the same time that one plays the [sounds of a] harp, flute and bassoon on the harpsichord, the other accompanies [by playing] the part of the violin on the pantalon or lute. The most remarkable of all, however, is that the harpsichord and pantalon can be played at the same time. . . . In strength and variety of instruments it is similar to a complete small orchestra.

Milchmeyer went on to offer his readers a collection of music he had assembled that was suitable for performance on this instrument, including works by ‘den berühmtesten Tonkünstlern’ (the most famous composers) such as ‘Bach, Bocherini, Eckard, Edelman, Lichner, Forckel, Gluck, Mozart, Schobert, Schroeter, Sterkel, Vogler’ and others.Footnote 50 Precisely what repertoire this collection might have included must remain a matter of speculation.Footnote 51 But to judge from Milchmeyer's description of the performance practice – one player takes the harpsichord part while the other accompanies him by playing the violin part on the pantalon – it seems likely that his collection of suitable music included two-keyboard arrangements of obbligato trios.

Latcham has shown that in the eighteenth century a ‘substantial number’ of instruments combining harpsichord, piano and other mechanisms were built, and that harpsichords were often modified to include a hammer mechanism as well as, or instead of, a plucking mechanism.Footnote 52 However, even in the absence of such instruments, the ideal of timbral variety could be realized just as easily on two separate keyboard instruments with different mechanisms. After all, players of keyboard duos would have needed two instruments in any case; if they were wealthy enough to own two harpsichords, it is just as likely that they would have owned one harpsichord and one piano. This was evidently the case with Sara Levy, who still owned both harpsichords and pianos as late as 1794.Footnote 53

The Bach organ trios hold an important place in this instrumental and musical world. Although Bach did not designate the registrations for organ performance, there is evidence that a diverse registration involving timbral contrast would have been appropriate. Adlung, in his extensive discussion of registration, exclaimed in frustration, ‘Demnach sehe ich nicht, warum etliche Organisten immer bey einerley bleiben. Die Veränderung ist und bleibt doch die Seele der Musik’ (I don't see why many organists always stay with the same [choice of registration]. Variety is and remains the soul of music).Footnote 54 Adlung's endorsement of Veränderung may be read as an allusion both narrowly, to the art of registration at the organ, and broadly, to variety as an artistic ideal.Footnote 55

A source contemporary with Sebastian Bach indicating some very colourful registrations for organ works is the Harmonische Seelenlust of Georg Friedrich Kauffmann. As Philippe Lescat has suggested, Kauffmann's registrations could be modified to suit the capacities of particular instruments; nevertheless, they provide important evidence of the role of registration in bringing out the different voices within a polyphonic composition.Footnote 56 Similarly diverse registrations are called for in the trios à trois repertoire of the French organ school, which generally prescribe separate timbres for each of the three lines.Footnote 57

It is well known that some of the movements of Bach's organ trios originated as works for mixed instrumental ensembles – a precedent, perhaps, for a varied registration in which performers would have juxtaposed distinct timbres for each of the two melodic lines, with a third for the bass line executed on the pedals.Footnote 58 Nineteenth-century sources took this for granted: the version of the trios issued in England by Wesley and Horn in the early nineteenth century was accompanied by an advertisement for the sonata bwv525 which states that ‘The trio was . . . performed by the matchless Author in a very extraordinary Manner; the first and second Treble Parts he played with both Hands on two Sets of keys, and the Bass . . . he executed entirely upon the Pedals, without Assistance’.Footnote 59 While the authors of this advertisement were most impressed, as David Yearsley points out, by Bach's feet, they report what must have been too obvious for German sources to state explicitly – namely that each of the soprano parts was played on its own manual, with its own distinct timbre.Footnote 60

To judge from a description provided by Forkel, Bach's own approach to organ registration was a mystery to others of his generation, though John Koster has shown recently that his harpsichord playing probably involved the widest variety in registration available on those instruments.Footnote 61 Even if it cannot be proven definitively that Sebastian Bach himself would have applied a mixed registration involving timbral contrast to the two melodic lines of his organ trios, Adlung's statement and these other examples of diverse timbres in registrations of organ music suggest that during and after Bach's lifetime, such performance practices were certainly possible.

Taken together, these principles of organ registration, Milchmeyer's description of his instrument as capturing the sounds of an orchestra, and the general pursuit of timbral variety in keyboard music of all kinds suggest that we can, in fact, discern something of the repertoire for combination keyboard instruments. Whatever else they were used for – and I think works such as Friedemann's concerto for two keyboards, Fk10, are likely candidates – they were probably also used for arrangements such as the ones described by Couperin. Harpsichord registrations often allowed for the use of a variety of timbres, such that the diversity of sounds in organ registrations could be recreated to some extent in an arrangement executed on a two harpsichords, or on a simple double harpsichord.Footnote 62 Combination instruments, however, could enhance this timbral variety, allowing players of keyboard-duo arrangements to explore new combinations of sounds that helped them to retain the character of organ registrations.Footnote 63 Whether these were performed on a single combination keyboard instrument such as the vis à vis or on two separate instruments, each with its own mechanism (for example, a harpsichord and a piano together), a mixed instrumentation would capture the ideal of timbral variety.

In the keyboard-duo arrangements of the Bach organ trios, a combination of harpsichord and piano allows each voice to express its own identity while still forming part of the ‘ensemble’. Brief solo episodes bring individual voices out of the texture, but in general the thematic material is harmonized and the figuration of the two lines richly intertwined. (That the keyboardist not playing the melodic solo should be playing a basso-continuo accompaniment is suggested by the manuscript of the Graun sonata in C major in the two-keyboard arrangement, cited above, which contains a complete set of figures for such passages.)

In keyboard-duo arrangements of other trios, the harpsichord–piano combination would have been equally in line with the aesthetics of the repertoire. Especially in works for flute and obbligato keyboard, including the sonata Wq87 of C. P. E. Bach discussed above, it would be appropriate for the piano, with the ‘flute-like quality’ noted at the time, to play the flute part and the bass line, while the harpsichord retains its original part. Any number of the trios of the late eighteenth century – whether originally conceived as obbligato or continuo works – would receive a fresh interpretation in this configuration, and, in keeping with the ad libitum registration practices that I have described here, the timbres of these works could be reinvented with each performance. In keyboard-duo arrangements, writers of the period suggest, the full palette of timbres available within a chamber group – or, indeed, within an organ or even an orchestra – would be available to players of two similar instruments. The choice among a wide array of mechanisms and stops on keyboard instruments offered an opportunity for builders, players and listeners to imagine and reimagine the expressive potential of their medium. Combination instruments likewise offer a model for the juxtaposition of single-mechanism instruments in the two-keyboard repertoire. Although not prescribed by composers or arrangers, these combinations represented one important possibility for instrumentation of the keyboard-duo repertoire, and, as Milchmeyer and others suggest, they were especially useful for conveying timbral variety in arrangements.

SYMPATHY AT TWO KEYBOARDS

Despite Couperin's protestations about the difficulties of assembling an ensemble of musicians able to play trios with continuo, the keyboard-duo configuration, clearly, could only be used in homes that were wealthy enough to afford either two separate keyboard instruments or a single combination keyboard instrument. The Itzig family was among the wealthiest in Berlin; it is no surprise that Sara Levy and her sisters could afford multiple keyboard instruments, and, indeed, their collections reflect a special interest in this medium.Footnote 64 Levy is thought to have commissioned the Wq47 concerto for harpsichord and piano by C. P. E. Bach, and to have played this work, along with other double concertos, with her sisters. With their widely admired virtuosity, the Itzig sisters were able to execute such difficult works despite their amateur status, and it is quite possible that they played other concertos by the Bach family using the same combination of harpsichord and piano that is spelt out explicitly in Philipp Emanuel's concerto, as well as in the organ trios discussed above. Indeed, it seems likely that if the concerto Wq47 had ever been published, its specific registration for harpsichord and piano together would have been omitted, and the parts designated simply for ‘Clavier I’ and ‘Clavier II’.Footnote 65 (The published works for two keyboards and orchestra by Henri-Joseph Rigel, which do specify harpsichord and piano together, also suggest an alternative instrumentation on the title-page.Footnote 66 )

The financial obstacles to the acquisition of two keyboard instruments must help to explain why keyboard duos – including both compositions intended for that configuration and arrangements of the sort that I have been describing – circulated primarily in manuscript. It is worth noting, too, that the four-hand keyboard tradition, which reached its pinnacle in the nineteenth century, had some precedents during this earlier period, as composers perhaps sought out the same pedagogical and sentimental values attributed to the keyboard duo in duets for two players at a single instrument.Footnote 67 The connection between four-hand music and keyboard pedagogy is suggested by works such as Haydn's Il maestro e lo scolare (1778) in which the upper part, representing the student, mimics each gesture of the lower part, played by the teacher. Yet there must have been a sufficient number of households or institutions that possessed two keyboards to justify the publication of works like Johann Gottfried Müthel's Duetto für 2 Claviere, 2 Flügel, oder 2 Fortepiano (1777) and Mozart's sonata for two keyboards, k448 (which, as noted above, was published posthumously in 1795).

Indeed, it was not just in homes as wealthy as that of the Itzig family that two or more keyboard instruments could be found. As the accounts of Wagenseil, Couperin and, of course, the Bach family suggest, numerous professional musicians owned more than one keyboard instrument, and they used these in training their students.Footnote 68 Johann Mattheson, in his Kleine General-Bass Schule of 1735, acknowledged the practical difficulties of using two keyboards together in pedagogical settings, yet he still advocated such a usage:

Lernet jemand auf der Laute; sein Meister spielet auf einer andern Laute zu gleicher Zeit mit ihm. Lernet jemand auf der Violine; sein Meister streicht auf einer andern Violine dazu. Singet jemand; sein Meister singet mit u.s.w. Nur das eintzige Clavier hat dieses Glück selten, oder gar nicht, daß der Lehrende und Lernende zusammen auf einerley Art Instrumenten spielen. Setzte man gleich zwey Clavicordia neben einander, so ist doch die Entfernung beider Werckzeuge Schuld, daß man sich, wegen des Raums, so sie einnehmen, die Griffe nicht wol absehen kann. Dennoch, wo zwey Claviere von mittelmäßiger Grösse zu haben sind, ist es freilich wol gethan, sie neben einander zu setzen, und zu gebrauchen.Footnote 69

If one is learning to play the lute, his teacher plays another lute at the same time with him. If one is learning the violin, his teacher bows on another violin with him. If one sings, his master sings along, and so on. The clavier alone rarely, or never, enjoys this good fortune, that teacher and student play together on the same variety of instrument. Even if one were to set two clavichords next to one another, the distance between the two keyboards is such that the [players] cannot see well enough to copy the movement of the hands, for they take up [so much] space. Nevertheless, if two claviers of moderate size can be had, it is of course good to set them near each other, and to make use of them [together].

This passage comes from Mattheson's short treatise on the performance of thoroughbass, so it is natural that he should have in mind the demonstration and learning of thoroughbass techniques at two keyboards, rather than compositions or arrangements with obbligato right-hand parts. Nevertheless, there is an important similarity between these cases: like two keyboard players performing arrangements of the type described by Couperin, Mattheson's two players realizing a single continuo part would share the same bass line, but they would provide distinct, yet overlapping and complementary, right-hand parts. Learning to respond to the same musical stimulus – the bass line – the two players would need to accommodate their responses to one another. Mattheson's description of the physical placement of the two instruments is also telling: two players using Stein's vis à vis would face each other, viewing facial expressions and movements of the upper body, but not the movements of the fingers. Even in Mattheson's description, with the two keyboards right next to one another, the size of the instruments means that ‘the [players] cannot see well enough to copy the movement of the hands’. In both cases, musicianship must be cultivated through listening rather than seeing. Coordination of sound and sentiment would lead to coordination of finger technique.

Quite another image, useful for contrast, is given by Burney's account of the orphans who studied music in the conservatorio of St Onofrio in Naples. There, although there were numerous harpsichords (along with other instruments) in a single room, there was no one to guide the boys through their practice or instruct them in a common musical purpose. As Burney wrote,

In the common practising room there was a Dutch concert [musical chaos], consisting of seven or eight harpsichords, more than as many violins, and several voices, all performing different things, and in different keys. . . . Out of the thirty or forty boys who were practising, I could discover but two that were playing the same piece.Footnote 70

This scene is a far cry indeed from the orderly practice and instruction described by Mattheson, or the images of family music-making evoked by Couperin. Moreover, as Burney explained of the Neapolitan orphans, it was not just in their ordinary practice that the boys lacked instruction and coherence; the problem was so much a part of their system of that it prevented them from developing a good sense of musicianship, and this lacuna was evident in their public performances as well:

The jumbling them all together in this manner may be convenient for the house, and may teach the boys to attend to their own parts with firmness, whatever else may be going forward at the same time; it may likewise give them force, by obliging them to play loud in order to hear themselves; but in the midst of such jargon, and continued dissonance, it is wholly impossible to give any kind of polish or finishing to their performance; hence the slovenly coarseness so remarkable in their public exhibitions; and the total want of taste, neatness, and expression in all these young musicians, till they have acquired them elsewhere.Footnote 71

Despite Burney's frank description, the images that he calls up are poignant: as orphans, the boys of St Onofrio lacked the family that would have allowed them to make music in the context of such close relationships. And although they received instruction in music in the orphanage and had harpsichords to practise on, their teachers – out of negligence? or simply a lack of time? – failed to cultivate in them the ‘taste, neatness, and expression’ that they would have gained elsewhere. Their cacophonous practice sessions at multiple keyboard instruments were both a cause and a reflection of their deficiencies in the communication of musical sentiment.

Here it must be noted that the family as a sentimental unit, connected through emotional bonds and ideals of love and sympathy, emerged precisely during this period. Treatises on education by Jean-Jacques Rousseau and others, which spread widely throughout Europe, advocated family roles and relationships that would foster, as Loftur Guttormsson writes, ‘a solid intellectual and moral education instilling in [children] self-discipline, industry, and a sense of responsibility’.Footnote 72 The emotional bonds of the family would extend to sympathetic relationships with people outside the family, leading to the growth of a moral society. The rise of the family in this modern sense was made possible, among other things, by shared experiences of the arts. Alongside the sentimental novel, which worked out the relationships between individuals and the family, musical practices also articulated the bonds between parents and children, or among siblings.Footnote 73 Chamber music not only reinforced the sympathetic bonds among family members – both on the level of individual families and on the level of society as a whole – it also helped to create such bonds.

Although communication of sentiment, and the sympathy or ‘fellow-feeling’ that made it possible, were guiding principles of music throughout the eighteenth century, there are reasons to consider keyboard duos – and arrangements of chamber works for keyboard duo in particular – as a special manifestation of these principles. Keyboard-duo arrangements of trios of the sort described by Couperin and borne out by the manuscript evidence that I have presented involved distinctive musical processes that mirrored and facilitated eighteenth-century ideals of sociability. United by a common musical framework, and executing identical bass lines, the two keyboard players could use their distinct melodic lines to enact a process of musical conversation. The result was a musical metaphor for the social-aesthetic ideal of sympathy, through which individuals could be united in a shared experience even as they acknowledged and articulated their distinct identities.

The congruence of both the physical and the emotional aspects of playing in a keyboard duo is what sets this performance practice apart from other chamber-music practices of the late eighteenth century. The importance of both of the physical and the sentimental aspects of arrangements has been highlighted by other writers; addressing arrangements of orchestral music for chamber groups, Wiebke Thormählen has suggested that performances of arrangements allowed players to internalize the social and moral messages of music (manifested not just in vocal music, but also instrumental) more fully than they would have done by listening. She explains, ‘As taste and moral sentiment were understood to be based in physical sensation, an actual physical engagement with art would enhance their effect’.Footnote 74 She continues:

The idea that engaging with art involved an inner [mental] act that might be intensified if it were also enacted physically was rooted in models of the interaction of body and mind that persisted in popular belief, even though they were being reconsidered in medical discourses. The passions remained central to an individual's physical and emotional life, producing an inextricable bond between body and soul, physicality and emotions.Footnote 75

Elisabeth Le Guin, too, has explored the eighteenth-century notion that sentiments may be shared through both physical and emotional sympathy. Music became an ‘extended metaphor for a hypersensitized and self-conscious model of community’. As Le Guin suggests, ‘sensitive bodies lent themselves very readily to musical metaphors – in particular the likening of nerve fibers to vibrating strings. . . . What is new in the eighteenth-century use of this metaphor, however, is its emphasis on the idea of bodies resonating, not only with God or with the organization of the universe, but in sympathy with one another’.Footnote 76 Seen in this light, it would be difficult to conceive of two people joining each other in music-making and avoiding the social metaphor implicit in their shared activity. Nor is such avoidance called for. Theorists across Europe – David Hume and Adam Smith in England, Denis Diderot and Sophie de Grouchy in France, Moses Mendelssohn and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing in Germany, to name just a few – understood the arts as a testing ground and site of construction for an enlightened society, in which individuals with distinct identities would achieve understanding and common interest through sympathetic relationships.Footnote 77

While such relationships could be forged and reinforced through the practice of any type of chamber music, the keyboard duo occupies a special place in this scheme because of the simultaneous physical and sentimental sympathies that it engendered. I base this observation not only on the eighteenth-century evidence that I have presented concerning the historical usage of two-keyboard arrangements, but also on my experience as a chamber musician in both mixed ensembles and in a piano–harpsichord duo. In particular, arrangements of the sort that Couperin described represent a culmination of both the physical and the emotional aspects of sympathy: as players we must deal in a kinesthetic manner not just with the music itself (as in the arrangements of orchestral works that Thormählen discusses), but with each other, coordinating the expressive aspects of our playing through technical, tactile means. The bass line serves as a unifying force, linking us through both physical and sonic parameters, while the distinct treble lines force us to understand and respond to the bass line in distinct ways. While all duos on two similar instruments allow for the articulation of both physical and musical sympathy, arrangements for keyboard duo in the configuration discussed here shape and constrain our hands and our imaginations in a singular manner. In playing these arrangements, I have heard echoes of these lines by Mendelssohn on sympathy, representative of a widespread position in the late eighteenth century:

Es kann keine Liebe, keine Freundschaft, ohne diese mildthätige Vervielfältigung seiner selbst bestehen. Die Liebe ist eine Bereitwilligkeit, sich an eines andern Glückseligkeit zu vergnügen. . . . bey der Freundschaft wächst diese Bereitwilligkeit bis zur Neigung, uns völlig an die Stelle unseres Freundes zu setzen, und alles, was ihn betrift [sic], so zu fühlen, als wenn es uns selbst beträfe. . . . Weit gefehlt, daß der Grundsatz der Vollkommenheit das gegenseitige Interesse moralischer Wesen aufheben, oder nur im geringsten schwächen sollte; er ist vielmehr die Quelle der allgemeinen Sympathie, dieser Verbrüderung der Geister, wenn man mir diesen Ausdruck erlaubt, die ihr eigenes und gemeinsames Interesse dergestalt in einander verschlinget, daß sie ohne Zernichtung nicht mehr getrennet werden können.

No love, no friendship can exist without the benign reproduction of itself. Love is a readiness to take pleasure in someone else's happiness. . . . In the case of friendship this readiness grows into the inclination to put ourselves completely in the position of our friend and to feel everything that affects him as though it affected us ourselves. . . . Far from canceling the mutual interest of moral entities or even weakening it in the slightest, the basic principle of perfection is instead the source of universal sympathy, of this brotherhood of spirits – if I may be allowed the expression – which engulfs and entwines each person's own interest and the common interest in such a way that they can no longer be separated without destruction on all sides.Footnote 78

The arrangements require that my partner and I ‘put ourselves completely in the position of our friend’, hearing our shared musical material and anticipating the movements of each other's fingers in accordance with the progress of the music. The mistake that I make most often in our rehearsals (and once, so far, in performance) is to play the melody line that belongs to my partner. I hear her music as part of my own, and I seek to create it – to enact and experience it – with her. At the risk of indulging such errors, I would suggest that they are part of the process of bringing this music to life. Serendipitously, these errors have led me to sympathize not just with my collaborator, but with the aesthetics of sympathy within which they might have been understood in the eighteenth century.

Such shared experiences would articulate and reinforce the family relationships of such experienced players as Sebastian Bach and his children or François Couperin and his, even as they cultivated the technical and expressive skills of Wagenseil's eleven-year-old student. It is not hard to imagine instruction and amusement within the Bach family in such terms – and little wonder that they were players, in one way or another, in the creation and advocacy of music for two keyboards. In the case of Sara Levy, one might envision her playing keyboard duos as a young student of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, and playing them again with her sisters as an expression of their family bond. How better to communicate mutual understanding and various shades of feeling than in the constant exchange of thematic material that characterizes the music shared by the two players, each at his or her own keyboard, listening and responding? Other familiar families also come to mind: Nannerl and Wolfgang, Fanny and Felix. Keyboard duos, it seems, allow teacher and student, father and son, sister and sister, to rehearse the negotiation of the self within the ensemble, as players come face to face with both their differences and their family resemblances.