Disclaimer

The views expressed in this publication are those of invited contributors and not necessarily those of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries. The Institute and Faculty of Actuaries do not endorse any of the views stated, nor any claims or representations made in this publication and accept no responsibility or liability to any person for loss or damage suffered as a consequence of their placing reliance upon any view, claim or representation made in this publication. The information and expressions of opinion contained in this publication are not intended to be a comprehensive study, nor to provide actuarial advice or advice of any nature and should not be treated as a substitute for specific advice concerning individual situations. On no account may any part of this publication be reproduced without the written permission of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries.

1. Summary of the Paper and Conclusions of the Working Party

1.1 Introduction

The risk margin is part of the Solvency II regime which came into force in the European Economic Area (EEA) in 2016. It has proved to be controversial in the United Kingdom (UK), where it has been criticised for being too large and too sensitive to interest rate movements, particularly in relation to business subject to long-term guarantees, such as annuities.

This paper examines the need for the risk margin and considers a range of possible alternatives, ranging from amendments to the calibration of the existing methodology to more radical changes. The working party hopes that the paper will inform the debate both in the context of reviews of Solvency II and more particularly within the UK, if changes to the solvency regime are under consideration following Brexit – the withdrawal of the UK from the European Union (EU).

1.2 The Risk Margin and Its Problems

1.2.1 Overview of the risk margin

The risk margin is part of the technical provisions under Solvency II. The technical provisions are defined as the amount required to be paid to transfer the business to another undertaking, in order to ensure that they meet the Solvency II requirement for market consistency. The risk margin is the difference between the technical provisions and the best estimate liabilities (BEL).

In practice, the technical provisions cannot normally be directly calculated as the transfer amount, and the risk margin is determined separately from the BEL, using a specified proxy methodology. The proxy methodology chosen for Solvency II is called the cost-of-capital method. It defines the risk margin as the discounted value of the future cost of capital relating to risks (other than hedgeable market risks) required to be held under Solvency II rules by the hypothetical transferee company (called the reference undertaking under Solvency II). In other words, the existence of the risk margin allows for the reference undertaking to be fully capitalised to Solvency II standards after the transfer.

Section 2 of the paper examines the purpose of the risk margin and sets out a detailed description of its calculation. This section is supplemented by Appendices B and F.

Appendix B describes the initial development of the risk margin under Solvency II, and in particular indicates why the cost-of-capital method was selected ahead of alternative methods. Appendix F is for reference: it lists the parts of the Solvency II Directive, Regulations and Guidance which are directly relevant to the risk margin.

The impact of the risk margin in the UK was mitigated on the implementation of Solvency II by the Transitional Measure on Technical Provisions (TMTP), which was introduced as part of the long-term guarantee measures package. For most UK insurers, the TMTP enables the introduction of the risk margin in respect of existing business to be scaled in over 16 years.

1.2.2 Summary of problems

Following the implementation of Solvency II, it became clear that for UK life insurers, the risk margin was both larger than expected and very sensitive to interest rate movements. The UK regulator, the Prudential Regulatory Authority (PRA), pointed out that between December 2015 and September 2016, the overall risk margin of major UK life firms rose from £30bn to £44bn (Rule, Reference Rule2017).

Although existing business was protected by the TMTP, there is significant concern about the risk margin causing volatility of insurers’ balance sheets, resulting in reinsurance of longevity risk outside the EU and encouraging procyclical investment behaviour.

Furthermore, new business is fully exposed to the risk margin, and there is concern about the impact on the price of annuities, including bulk purchase annuities. These not only form a major source of new business for many life insurers, but are very important to the overall system for retirement provision in the UK, both in relation to individuals and for pension schemes wishing to close down or transfer risk.

These criticisms of the risk margin are discussed in detail in section 3 of the paper, which also includes a summary of the treatment of the criticisms of the risk margin in post-implementation reviews of Solvency II.

1.2.3 Political ramifications

As a result of these concerns, the risk margin became politically significant. It was even specifically mentioned in a letter from the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Phillip Hammond, to the Governor of the Bank of England (Hammond, Reference Hammond2017), which included the following:

The government also welcomes the work being undertaken to examine the design of the Risk Margin feature in the insurance regulation to limit the sensitivity to changes in the risk-free interest rates, which will have beneficial macroprudential and financial stability impacts.

In 2016 −17, the Treasury Committee of the House of Commons carried out an inquiry into EU Insurance Regulation in order to consider the extent to which Solvency II would be appropriate to the UK after Brexit, and whether changes to the regime should be considered.

The risk margin featured strongly in this inquiry, and written and verbal submissions relating to the risk margin were made by many parties, including the PRA, the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA), the Association of British Insurers (ABI) and a number of insurers. The inquiry concluded that criticisms of the risk margin were justified, and that the PRA should act to resolve them (Treasury Committee, 2017b).

The PRA responded in February 2018 that it is considering changes to the risk margin (PRA, 2018), but in June 2018 it added that it cannot act at present owing to uncertainty about the future relationship of the UK with the EU (Woods, S., Reference Woods2018). This situation remains unchanged.

More details about the Treasury Committee inquiry are given in section 3.5.2.

1.3 The Working Party

In the light of the problems that had been identified and the political background, our working party was established in September 2017.

Our brief was to address two key objectives, in the context of life insurance business:

What can be done to fix known issues with the risk margin, either within Solvency II or using potential post-Brexit flexibility?

What should be the purpose of the risk margin and how can that purpose best be fulfilled?

We aim to address both of these objectives through the production and presentation of this paper.

In order to inform our conclusions, we carried out a survey of life insurers. The results of the survey are given in sections 4 and 6 of the paper, with a list of the questions in Appendix C.

We have also developed a simple model to illustrate features of the risk margin and assess the impact of various alternatives – the model is described in section 5 of the paper, with more detail in Appendix D. The main results of the model are presented throughout the paper.

In addition to the above, we have

contributed to the response from the IFoA to a consultation by the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) reviewing Solvency II;

presented at Current Issues in Life Insurance (CILA) in the form of a debate and at the IFoA Life Conference; and

engaged in a debate on the risk margin in The Actuary magazine.

1.4 Potential Amendments to the Risk Margin

In section 6 of the paper, we analyse a number of alternatives for re-calibration within the framework of the existing Solvency II Directive, retaining the cost-of-capital methodology.

These include

reducing the assumed cost-of-capital rate;

allowing the cost-of-capital rate to vary with interest rates; and

amending the discount rate from the risk-free rate.

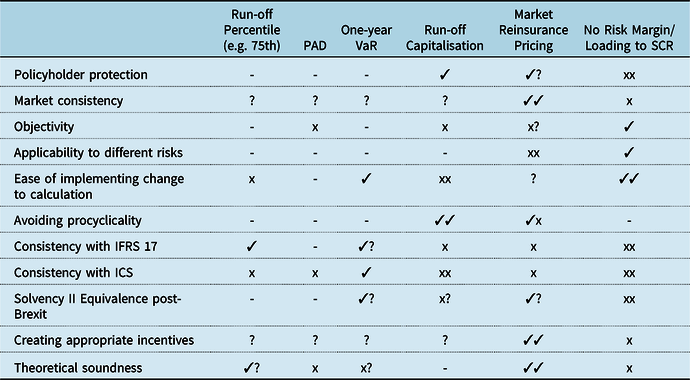

The working party’s view is that more fundamental changes should be considered. In section 7 of the paper, we examine the following alternative methodologies:

a run-off percentile approach originally considered for Solvency II, for example, the risk margin might be defined as the difference between the 75th percentile of the probability distribution of the liabilities and the BEL;

a Provision for Adverse Deviation (PAD), for example, the impact of a specified adverse scenario;

a Value-at-Risk (VaR)-based approach;

a run-off capitalisation approach;

market reinsurance pricing in relation to longevity risk; and

removal of the risk margin altogether or replacing it with an increase in the solvency capital requirement (SCR).

In addition, section 7 includes a description of the margin over current estimate (MOCE), which is under consideration for the framework for International Capital Standards (ICS) being developed by the International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS). To supplement this, Appendix E includes an overview of measures similar to the risk margin used in various solvency regimes outside the EEA.

In section 8 of the paper, we consider the properties of a desirable risk margin. We also evaluate the alternatives considered in sections 6 and 7 against these properties.

1.5 Practical Issues

Appendix A considers briefly a number of practical issues relating to the risk margin.

In section A1 of this Appendix, we consider the calculation of the risk margin and describe some of the simplifications which are necessary to carry out the calculations in practice.

In section A2 of this Appendix, we consider the question of stressing the risk margin in calculating the SCR.

An analysis of whether and how the risk margin can be hedged is given in section A3 of this Appendix.

1.6 Impact of Brexit

The future of the risk margin in the UK is likely to be highly dependent on Brexit.

At the time of writing, it remains unclear when and in what form Brexit will take place, and indeed even whether it will happen at all. As indicated in section 1.2.3, uncertainty over Brexit is already inhibiting the PRA from implementing changes considered to be desirable.

However, one of the working party’s aims in producing this paper is to inform any future debate on the development of the risk margin, and so we have to consider all possible outcomes.

One outcome is that following Brexit, the UK will have a relatively free hand in determining the solvency regime that is considered appropriate for UK insurers. In that situation, given the consensus in the UK that the risk margin is flawed, the alternative methodologies described in section 7 of the paper should be considered.

It is possible that following Brexit, the UK wishes to obtain Equivalence with Solvency II. Although Equivalence is likely to be more relevant to general insurance business than life business, a major change to the risk margin for life business may be a significant barrier to this. This could constrain potential changes to the risk margin in the UK.

Furthermore, the outcome of Brexit may be that the UK is constrained to be subject to Solvency II, either through a UK–EU agreement covering insurance business or through the UK remaining a member of the EEA. In this case, the UK would have no direct influence on the future of Solvency II, including the risk margin, and it is likely that changes to the risk margin to resolve problems specific to the UK would be difficult to achieve.

Nevertheless, irrespective of whether or not the UK remains a member of the EU, the working party hopes that this paper will be of direct use to EIOPA in reviewing the risk margin within the forthcoming review of Solvency II. We also expect the paper to inform the profession’s response to the consultation for the review.

1.7 Conclusions

The working party’s analysis has not reached a firm conclusion on one specific alternative method. Indeed, the different objectives are at times in conflict, so there is no one solution that meets all of them. Furthermore, the range of possible changes will be dependent on the outcome of Brexit.

Nevertheless, having regard to our evaluations of the various alternatives, the working party sees merit in considering the following changes:

to allow for an automatic change in the assumed cost-of-capital rate when risk-free rates change;

to allow a prudent illiquidity premium to be used in the calculations of the projected future SCRs and in the risk-free rate used in discounting the future costs of capital;

to allow certain longevity risk to be treated as hedgeable and the relevant part of the risk margin to be replaced by the cost of the hedge; or

to move to, or to allow as an alternative, the Percentile-MOCE, which is being considered under ICS.

More details are given in section 8.4, including our reasoning for selecting these alternatives.

The working party believes that a risk margin in some form is necessary. However, our view is that striking the balance between protecting policyholders and ensuring value for money is primarily a political choice, which affects the definition of both the risk margin and the SCR. This choice can be reflected in the calibration of any method that may be chosen. We hope that this paper will be useful in informing any deliberations regarding this balance.

1.8 Literature Review

A brief literature review is given in Appendix G.

2. The Risk Margin – Purpose and Calculation

2.1 The Case for a Margin

The idea that people are risk-averse is a well-known concept in many branches of economics and finance. Given a choice between receiving a guaranteed £50 and spinning a coin to decide whether they receive £100 or nothing at all, we expect the majority of people to choose the guaranteed amount.

We similarly expect firms to prefer liabilities where the value is known with certainty, rather than liabilities where the value cannot be known in advance. It seems sensible to reflect this preference in the value placed on the liabilities, with this value reflecting not only the expected cost, but also the uncertainty around this cost.

In the Solvency II framework, the starting point for determining technical provisions is to project a set of best estimate cash flows, each of which represents the mean outcome. Uncertainty around market risks is allowed for using a risk-free discount rate to value these cash flows, albeit subject to adjustments. The risk margin is then intended to reflect the “price” that is placed on the uncertainty relating to non-hedgeable risks.

We believe, therefore, that the underlying purpose of the risk margin is to ensure that technical provisions are struck on a market-consistent basis, that is, that a market price of risk is incorporated in respect of all risks, not only those risks for which deep and liquid markets exist. The hypothetical construct of the reference undertaking (see section 2.3), under this interpretation, is simply a means to arriving at a transfer value for the firm’s liabilities, rather than an end in itself. We now consider market consistency in more depth.

2.2 Market Consistency of Technical Provisions

One potential way in which the price of uncertainty can be included in the liability value is by setting the liability value equal to the amount required to settle the liability in the financial markets. If market participants are indeed risk-averse, then the amount for which they are prepared to settle the liability will presumably include the price of risk.

This is the approach taken by Solvency II, with Article 75, paragraph 1.(b) of the Directive stating that:

…liabilities shall be valued at the amount for which they could be transferred or settled between knowledgeable willing parties in an arm’s length transaction.

One key argument in favour of market-consistent valuation is that it results in liability values that reflect the cost of hedging the liabilities. If this is the case, and the insurer covers its liabilities with assets, then the insurer should be able to remove risk from its balance sheet should this become necessary, and thereby ensure that it does not default on its obligations.

An insurer’s solvency capital requirement (SCR) represents the 99.5% 1-year VaR in “basic own funds” (broadly equal to the excess of assets over liabilities). If an insurer holds own funds equal to its SCR then, in theory at least, there is a 99.5% chance of it surviving the next year. After 1 year has passed, if the insurer no longer covers its SCR it should still have sufficient assets to de-risk its balance sheet and therefore have a reasonable certainty that it will discharge its obligations in full.

This description of the Solvency II regime relies on the risk margin acting as a bridge between the SCR – which provides protection for policyholders over the next year – and the term of life insurance policies – which is typically much longer than a year.

While this description of the protection afforded by the Solvency II regime has a certain logic to it, it should be noted that this is only one interpretation of the intention behind the regime and this objective is not stated in the Solvency II Directive.

As indicated in Appendix B section B1.2, in developing the risk margin, the Committee of European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Supervisors (CEIOPS) – the forerunner of EIOPA – stated that it should have regard to a number of criteria including “achieving an appropriate level of policyholder protection over the run-off period of the liabilities” (CEIOPS, 2007, page 13). We should therefore also regard policyholder protection as an objective of the risk margin.

2.3 The Risk Margin Calculation

While a market-consistent valuation may look like an attractive option, the challenge it faces is that the cost of settling insurance liabilities cannot be observed directly from the financial markets.

This has required the architects of Solvency II to attempt to model this cost, and this modelled cost is necessarily dependent on a number of assumptions. Key features of the model are

the transfer takes place to a “reference undertaking” which has no assets or liabilities before the transfer, and which remains closed to new business after the transfer;

the reference undertaking will de-risk its assets so as to minimise market risk;

the reference undertaking is subject to Solvency II on an ongoing basis. It is required to hold technical provisions plus an SCR in respect of its remaining risks at all times – it therefore raises sufficient capital at the beginning of each year to cover this SCR for that year;

the amounts set aside to raise future capital are assumed to earn the basic risk-free rate of return inside of the reference undertaking;

however, the providers of capital require a return equal to 6% above the basic risk-free rate, since the capital is at risk (e.g. if assumptions are worse than best estimate).

These assumptions give rise to the following formula for calculating the risk margin:

where

CoC denotes the cost-of-capital rate – for which a value of 6% is prescribed;

SCR(t) denotes the projected SCR after t years;

r(t + 1) denotes the basic risk-free interest rate for maturity t + 1 years.

It should be noted that the Solvency II Delegated Regulation prescribes the risks that insurers should assume will be included in the reference undertaking’s SCR. The only exception to this is where the insurer has actually hedged the risk – in which case it is assumed that the reference undertaking will maintain the hedge. The prescribed risks are

underwriting risk;

market risk which cannot be eliminated through the de-risking of assets;

certain credit risks (including reinsurance); and

operational risk.

The Solvency II rules also set out a number of other key assumptions which insurers should make when calculating the risk margin:

any reinsurance contracts held by the insurer transfer to the reference undertaking;

the SCR is calculated using the same model as is currently used by the insurer: be that the standard formula or a partial or full internal model that has been approved by the regulator;

the SCR makes no allowance for the loss-absorbing capacity of deferred tax;

the reference undertaking adopts future management actions that are consistent with those of the insurer.

In addition to these explicitly stated assumptions, Huber and Kinrade (Reference Huber and Kinrade2017) point out that the risk margin methodology also relies on a number of implicit assumptions not set out in the rules. These include

capital is raised in the form of equity;

the investment return on the assets in which the capital is invested is not subject to tax; and

the cost-of-capital rate is charged only on the SCR even though, in practice, most insurers aim to hold a multiple of the SCR.

3. Perceived Problems with the Risk Margin

3.1 Challenges for the Insurance Industry

The risk margin has faced much criticism, from the UK life insurance industry in particular. In the working party’s experience, the bulk of this criticism has not focused on the assumptions underpinning the risk margin model but has instead focused on the result that emerges. Specifically, the risk margin is said to:

be too large;

be too volatile;

incentivise the transfer of risk to jurisdictions that are not subject to Solvency II;

be too inflexible.

This section discusses each of these areas in turn.

3.1.1 Size of the risk margin

The PRA has estimated that, as at 30 September 2016, the aggregate risk margin held across the UK life industry was around £44bn. (Rule, Reference Rule2017) This is a similar order of magnitude to the total benefit that the UK life industry derives from use of the matching adjustment (MA) (estimated to be £59bn in Woods, S., Reference Woods2017). Given how contentious the issue of the MA was when the Solvency II rules were being agreed, it is not surprising that the risk margin generates significant debate.

The introduction of the risk margin is one of key differences between the Solvency II regulatory regime and the Individual Capital Adequacy Standards which preceded it in the UK. All else being equal, the requirement to hold a risk margin results in insurers holding greater financial resources (i.e. technical provisions plus capital requirements) to support given set of obligations than would otherwise be the case.

Insurers understandably want to minimise those parts of their balance sheet liabilities and capital requirements which are over and above the expected cost of meeting obligations to policyholders. These additional provisions – which include the risk margin, the SCR and the margin between the expected return on assets and discount rate embedded in the calculation of the BEL – tie up financial resources and delay the distribution of profits to shareholders.

The industry often argues that delaying distributions to shareholders raises the cost of capital for insurers, and that this is passed on to policyholders in the form of higher premiums. The counterargument to this is that anything that delays distributions to shareholders will improve the chances that insurers will have sufficient financial resources to weather future adverse experience and ultimately fulfil their obligations to policyholders.

Striking a balance between protecting policyholders and ensuring that policyholders receive value for money is an ever-present challenge for legislators and prudential regulators. As indicated in section 2.2, policyholder protection is one of the objectives of the risk margin, and the design and calibration of the risk margin must therefore be considered in this regard. The working party’s view is that striking this balance is primarily a political choice, which affects the definition of both the risk margin and the SCR.

3.1.2 Volatility of the risk margin

The PRA has estimated that a 100 basis points (bps) fall in the basic risk-free rate would result in the risk margin increasing by around 27% (Rule, Reference Rule2017). Illustrative modelling carried out by the working party, as described in section 5, shows a similar picture. Figure 1 illustrates how the size of a typical risk margin might have changed from the point at which Solvency II came into force, up to the end of 2018.

Figure 1. Variation of risk margin with risk-free rates.

Insurers understandably dislike sources of volatility on their balance sheets. Volatile balance sheets increase the likelihood that an insurer may be temporarily unable to meet its SCR, an event which can disrupt the insurer’s business plans by, for example, preventing it from paying dividends, forcing it to change its investment strategy and/or restricting its ability to write new business.

It is worth noting that the risk margin is typically significantly more volatile than the BEL for the same business. This can be seen by calculating the risk margin as a percentage of BEL, and then looking at how this metric has moved from 31 December 2015 to the end of 2018. This is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Variation of risk margin as proportion of BEL with risk-free rates. Note: The RM/BEL ration for Dec 2015 is 7.7%. This is shown as 100% in the graph.

When faced with a volatile balance sheet item, the standard response is generally to look to hedge the volatility. The working party’s experience is that insurers have sometimes been reluctant to hedge the risk margin. Possible reasons for this include

there is a reluctance to lock in to long-term interest rates at a time when rates are low compared to historical levels. This is particularly true for the risk margin, which does not represent a true liability in the sense that it does not represent future payments to policyholders;

there is a cost associated with those hedging options which will simultaneously protect the insurer against future falls in interest rates and allow the insurer to benefit in a scenario where rates revert to historical averages; and

the risk margin does not normally feature as part of the accounting balance sheet under current International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and UK Generally Accepted Accounting Principles. It therefore seems that hedging the risk margin may increase the volatility of the accounting balance sheet.

In section A3 of Appendix A, we discuss some of the issues relating to hedging the risk margin.

3.1.3 Incentive to transfer risk by reinsurance (including to jurisdictions that are not subject to Solvency II)

While insurers may have generally been reluctant to hedge the risk margin, many annuity writers have been keen to reduce their risk margins by reinsuring longevity risk.

Publicly available data on reinsurance pricing are very scarce. Anecdotally, the working party has heard that longevity swaps may have a profit loading of around 5% built in to them. This means that each of the fixed leg cash flows that the insurer has locked into paying is around 105% of the equivalent floating leg cash flow that the insurer will receive if experience works out as it expects. The result of this is that entering into a swap might be expected to increase the BEL for the affected business by around 5%, but will also remove the longevity risk component of the risk margin. Reinsuring longevity risk will also remove the SCR component for this risk.

Illustrative modelling carried out by the working party suggests that the risk margin may be around 8.4% of the BEL for a typical annuity book (based on market conditions at 31 December 2018). If this is correct, then reinsuring the longevity risk could lead to an increase in BEL that is smaller than the increase in risk margin, resulting in an overall reduction in technical provisions. After the reduction in SCR has been factored in, it is understandable why insurers might believe that current reinsurance pricing is attractive.

As noted in section 2.1.2, the risk margin is intended to be an addition to the BEL which brings the total technical provisions up to the level required to allow the insurer to transfer the risk to another firm. The fact that some insurers have managed to reinsure longevity risk at a price that is materially lower than the technical provisions might be regarded as prima facie evidence that the risk margin is too large – at least for longevity risk.

An important question to consider is whether or not the increased use of longevity reinsurance since the start of 2016 has improved the security of policyholders’ benefits. When answering this question, it may be useful to consider why reinsurers might be able to offer such attractive pricing.

On the one hand, it has been postulated that current reinsurance pricing has been driven by a desire from reinsurers to acquire UK longevity risk, which they may regard as diversifying against their large back-books of United States mortality risk, in particular, senior life insurance. If one accepts this view, then increased reinsurance may well be in policyholders’ interests, since the longevity risk is ending up with firms that are better placed to manage it than UK direct insurers.

However, there is an argument that reinsurance pricing may reflect the fact that many reinsurers are based in jurisdictions that are not subject to Solvency II, and so do not have to hold a risk margin themselves. If this is the case, then the transfer of longevity risk would be a form of regulatory arbitrage, with the risk being transferred to jurisdictions with lower regulatory requirements. This may lead to lower protection for policyholders overall.

The view that increased use of longevity reinsurance may be driven by the introduction of the risk margin has been expressed by Bulley (Reference Bulley2016, page 10) on behalf of the PRA:

Solvency II potentially provides firms with an additional incentive to undertake transactions to transfer longevity risk by way of reinsurance (especially for new business which does not benefit from any transitional measures), as doing so may ease the requirement for holding a risk margin in respect of the reinsurance liabilities. We recognise that the current design of the risk margin makes it acutely sensitive to interest rate conditions.

The increased use of reinsurance does mean that the success or failure of an annuity writer is now predominantly driven by how well it manages its assets. This is a stark change from the traditional role of life insurers, which was to manage insurance risk.

3.1.4 Inflexibility of the risk margin

Another common criticism of the risk margin is that its calculation is inflexible. There is a single formula, with a single set of prescribed parameters, which must be used for all lines of life and general insurance business in all territories of the EEA.

This inflexibility can bring stakeholders into conflict. For instance, some in the life insurance industry have argued that the cost-of-capital rate should vary with interest rates. This could reduce the volatility of the risk margin for long-term business, since changes in the cost-of-capital rate may offset changes in the discount factors. However, when responding to this suggestion, EIOPA noted that this proposal would increase the volatility of the risk margin for short-term business, which is much more sensitive to the cost-of-capital rate than it is to the discount factor.

3.2 Potential Issues with the Market Consistency Objective

Section 3.1 outlines some of the main concerns expressed by the industry in relation to the risk margin. This section and section 3.3 examine how the method and assumptions used to calculate the risk margin have given rise to these concerns.

Before considering the detail of the method and assumptions, it is worthwhile considering whether the risk margin’s primary purpose – to ensure market-consistent valuation of technical provisions – is appropriate.

The following considerations are particularly relevant:

Is market-consistent valuation appropriate for life insurance liabilities? Arguably, there are aspects of the Solvency II regime which, paradoxically, are not market-consistent, despite its original intentions (although it is not yet known whether these aspects will be retained in the UK post-Brexit). Market-consistent valuation may also have other drawbacks, such as introducing additional volatility to the regulatory balance sheet. This can undermine insurers’ ability to invest through the cycle: the more the balance sheets deteriorate in times of stress, the greater the incentive to de-risk balance sheets in times of stress, which can lead to procyclical investment behaviour. Solvency II has recognised this and, in an effort to reduce excessive volatility, has introduced various concepts such as the MA and volatility adjustment (VA) which have moved the regime away from pure market consistency.

A common variant of the arguments against market consistency is that, while base liabilities should be struck on a market-consistent basis, solvency capital should be struck using a run-off obligation-based approach, causing the risk margin effectively to disappear from the stressed balance sheet. The Solvency II regime aims for a situation where each insurer has at least a 99.5% probability of surviving the next year (i.e. having assets in excess of its liabilities in 1-year’s time) and then being able to fully de-risk its balance sheet. There is, however, a question about whether this two-stage aim is too complicated. In particular, if this aim is to be achieved, then insurers will need to model the cost of transferring risk during times of stress. Given that one cannot even readily observe the current cost of transfer, and given the contention around the debate about how the current cost of transfer should be modelled, modelling the cost of transfer under stress is ambitious to say the least.

Why is mortality/longevity risk treated as non-hedgeable, whereas almost all market risks are treated as being hedgeable? Reinsurance markets are arguably deeper than a number of the markets from which market-consistent assumptions are derived, for example, long-term equity or property volatility. Should reinsurance pricing therefore be given greater weight within the calculation of technical provisions? If so, this can be incorporated in a number of different ways.

In general, it is worth re-considering the set of risks within scope of the risk margin calculation.

3.3 Critique of Risk Margin Method and Assumptions

As well as considering whether a market-consistent valuation is appropriate for technical provisions, it is also worthwhile discussing whether the method and assumptions used to estimate this market-consistent value are appropriate.

3.3.1 Cost-of-capital method

Several concerns around the cost-of-capital approach have been raised.

The risk margin is driven by the insurer’s own SCR whereas, in a traded market, the market price of risk would reflect the average risk preferences across all market participants. Under the current methodology, two insurers may hold different risk margins against similar blocks of business owing to differences in their internal models.

Similarly, an insurer’s risk margin may be reduced if its risks diversify. Thus, an insurer with both protection and annuity business on its books may hold a proportionately lower risk margin than one that has solely annuity business.

Given the existing allowance for the insurer’s own risk profile including diversification benefits, however, the current risk margin construction precludes diversification benefit between life and general insurance business within the same entity or group. This too is worthy of further consideration.

3.3.2 Explicit calibration assumptions

Criticism of the calibration of the risk margin has to date focused on the prescribed 6% cost-of-capital rate, that is, the relevance of historical equity risk premium data, and the analysis and conclusions drawn from it. Additional concerns have been raised relating to the constancy and “through the cycle” calibration of the assumption, and the implications for balance sheet volatility.

Also worthy of critical review is the requirement to use a risk-free discount rate, both in the projected capital requirements, and in the discounting of the resulting cost of capital amounts to the valuation date.

3.3.3 Implicit calibration assumptions

An implicit assumption is that the cost-of-capital rate itself is fixed. This reflects EIOPA’s desire to produce a through-the-cycle calibration. There is therefore no allowance for movement in the cost-of-capital rate within the one-in-200-year all-risks SCR scenario.

Another implicit assumption is that the aim of the risk margin is to ensure the security of the policy proceeds to full Solvency II standards for the complete run-off period. In other words, should a one-in-200-year event occur at any future point, there should be sufficient capital available to cover the SCR for the next year, and then similarly for further adverse events. Although this provides a high level of security to policyholders, a lower level of security, with correspondingly lower costs, could also be considered.

Finally, under the prescribed approach, the SCR is projected deterministically over the lifetime of the liabilities, based on best estimate assumptions. In reality, the future SCR is an unknown quantity with a statistical distribution. A stochastic calculation of the risk margin could well lead to a different result compared with the existing deterministic calculation.

Randomness in future SCRs is caused by all of the same factors affecting the base liabilities (interest rates, policies in force, etc.) as well as changes to the level of the 99.5th percentile stresses for the calculation itself. The level of stress applied could change for a number of reasons:

changing views on the nature of the risks, for example, new medical data suggests a greater variance in the distribution of mortality improvements than previously assumed; or

underwriting risks might not be stationary, for example, following an increase in assumed longevity, future 99.5th percentile increases might be lower (the “cancer can only be cured once” argument).

3.4 Impact of the Risk Margin on the Pricing of Annuities

The availability and cost of annuities is very significant to the system of retirement provision in the UK, and indeed to the economy as a whole.

Individual annuities still have an important role to play in retirement provision, although there are now alternative means of using built-up funds. In particular, they provide insurance against living longer than expected.

The bulk purchase annuity market enables company pension funds to transfer current or future pensions to insurers in order to remove longevity risk or indeed close down. This can be beneficial both for reducing risk to the sponsoring employer and improving the security of benefits for the members.

Furthermore, the provision of individual and/or bulk annuities is seen as an area of opportunity for the UK life insurance industry, at a time when other products are subject to competition from outside the industry.

However, concern has been expressed that these benefits are jeopardised by the size of the risk margin, which represents economic capital, the cost of which must be allowed for in pricing.

This concern was a significant theme in submissions to the Treasury Committee inquiry (see section 3.5.2).

However, the PRA, in its response to the Treasury Committee (PRA, 2018, page 11) stated

We have also examined whether Solvency II is having a detrimental impact on policyholders as firms pass on increased costs of regulation, looking first at annuities. We conclude that risk-free market interest rates and corporate bond spreads continue to be the dominant driver of annuity prices, and the relationship does not appear to have changed since Solvency II came into effect.

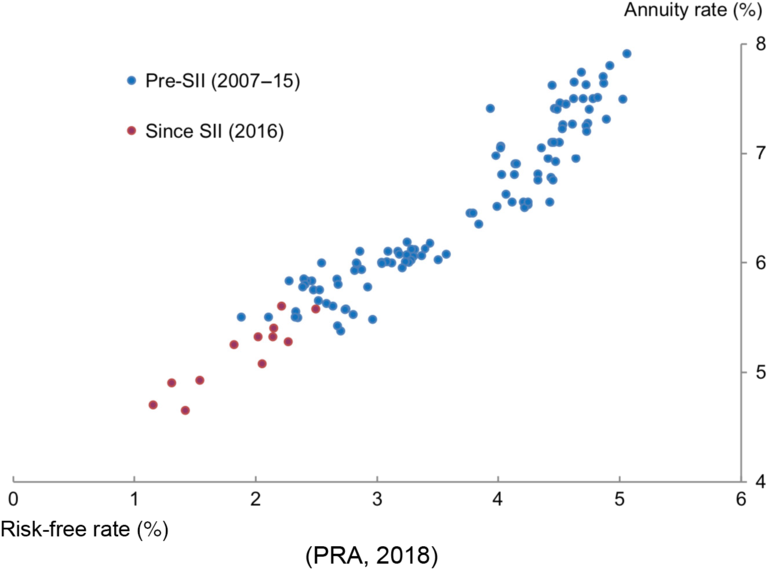

This conclusion was based on Figure 3. The working party’s view is that it is clear that interest rates continue to be the dominant driver, but the limited data in the figure do not conclusively indicate that the relationship has not changed.

Figure 3. Relationship between annuity rates and risk-free market interest rates.

3.5 Solvency II Reviews and Industry Proposals

During 2017 and 2018, there were two main enquiries into the operation of Solvency II generally, and the risk margin in particular.

-

1. EIOPA advice on specific items in the Solvency II Delegated Regulation

The consultation, which included the risk margin, took place in 2017 and EIOPA’s final advice was published in February 2018 (EIOPA, 2018).

2. In the UK specifically, the Treasury Committee inquiry into EU Insurance Regulation

This inquiry took place in the first quarter of 2017 and, following the General Election and the reconstitution of the Committee, the report was published in September 2017 (Treasury Committee, 2017b).

3.5.1 EIOPA advice

The Call for Advice from the European Commission (2016) to which EIOPA responded was generally focused on the Level 2 Delegated Regulation, rather than the Level 1 Directive, and also primarily on the “methods, assumptions and standard parameters used when calculating the Solvency Capital Requirement with the standard formula” (ibid., page 2).

Given the discussion below, it should be noted that there is a separate and wider-ranging review of the long-term guarantees measures, which is due for completion by 1 January 2021, that is, 5 years after implementation.

As part of the 2017−18 review, EIOPA was asked specifically on the risk margin to:

provide information on the relative size of the risk margin in insurers’ balance sheet;

assess if the methods and assumptions applied in the calculation of the risk margin continue to be appropriate, in view of a changed market environment. In particular, EIOPA is asked to review the cost-of-capital rate. (ibid., page 8).

Interested parties had two opportunities to respond to EIOPA’s consultation, first to the initial call for views and second to the draft advice.

The main frustration for respondents to the consultation, including the IFoA, was that EIOPA interpreted the scope of its advice too narrowly. To quote from the profession’s response, IFoA (2018, page 8), to which this working party had input:

The scope of the call for advice was very broad, with EIOPA asked to “Assess if the methods and assumptions applied in the calculation of the risk margin continue to be appropriate”. However, EIOPA’s proposed advice to the Commission focuses narrowly on whether the cost-of-capital rate parameter is consistent with market indicators.

Indeed, the final advice from EIOPA (2018, page 370) was that

The review of other aspects of the risk margin should be done as part of the review of Solvency II that the Commission is required to undertake after 5 years of implementation.

The conclusion of the review in relation to the cost-of-capital rate was that if anything that 6% rate is too low, but nevertheless, it should not be changed. This is discussed in more in detail in section 6.1.

This conclusion was accepted by the Commission who made no changes to the risk margin following the EIOPA review of the Delegated Regulation.

3.5.2 Treasury Committee inquiry

The Treasury Committee’s inquiry in 2016−17 was into the effect on the UK insurance industry of the introduction of Solvency II. The risk margin was a major theme of the inquiry.

The submission of the ABI (2016, page 3) included

Our top concern is the Risk Margin …: Its size and sensitivity to interest rate movements are both significantly higher than expected and reflect unintended consequences of its design. This makes the writing of new business, in particular annuities and other long-term guarantee-based products, unattractive to firms.

The submission of the IFoA (2016, page4) commented on the aims of capital frameworks:

Solvency capital frameworks seek to ensure that insurers are capitalised at a level which allows the survival of a rare event. However, should insurers then:

have sufficient margins to recapitalise, or

have sufficient assets to mean a solvent run-off is possible?

Solvency II adopts the former more stringent approach, but the cost of capital is ultimately borne by the consumer and the level of security which they would willingly pay for needs to be taken into account.

The IFoA (2016, page 13) commented further, specifically on the risk margin:

Although the purpose of the risk margin may seem reasonable, the mechanism and parameters chosen tend to result on excessively high risk margins that are disproportionately high for long duration business, such as annuities. We therefore agree that there is merit in revisiting the design of the risk margin.

A significant part of the risk margin is more of the nature of an additional capital requirement as opposed to an allowance for the cost of transferring liabilities. It is very sensitive to long-term interest rates, particularly when interest rates are low (as has been the case recently). This can drive behaviour (such as reducing longevity exposure in order to reduce the risk margin) that might not otherwise be taken, as it erodes insurer profitability and/or feeds back into pricing for consumers.

Andrew Chamberlain, chairman of the Life Board of the IFoA at the time, gave oral evidence to the Committee. His evidence included (Treasury Committee, 2017a, Question 17)

There is a trade-off between the level of security and the price the consumer has to pay for that insurance – it is an insurance against the failure of the insurance … The price the consumer has to pay for that is something that they will not get a choice in. That choice is made by the regulatory system.

Following the General Election, a new Treasury Committee was formed, which in September 2017 released its own report, (Treasury Committee, 2017b), based on the previous Committee’s work. The parts of the report relating to the risk margin are summarised below.

In contrast to the results of the EIOPA consultation, the Committee appeared to have more sympathy with evidence received from the industry, and in particular with issues caused to the annuity market by the risk margin.

The PRA’s evidence did not disagree with the diagnosis – indeed the Committee’s report indicates that Sam Woods, Deputy Governor for Prudential Regulation and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the PRA, stated that “the biggest and most obvious bug is the risk margin” (ibid., page 20) – but disagreed as to the ability to effect change.

The Committee’s recommendations relating to the risk margin (ibid., pages 54−57), made after analysing the evidence submitted, were not entirely clear on what the Committee believes can be achieved within the existing Solvency II rules, and what would require amendments to the rules or indeed the UK to have more freedom to set its own rules. Indeed, the Committee strongly encouraged the PRA and the industry to come to a mutual understanding on this.

However, the Committee believes, including in respect of the risk margin, that “an excessively strict interpretation of the requirements of Solvency II, and of its own obligations has limited [the PRA’s] thinking”. It also urged the PRA to take “more of a post-Brexit mentality”.

Specifically on the risk margin, the Committee commented that:

An additional margin which purports to represent the additional capital that a third party would need in order to run off the insurance firm in the case of an extreme event makes conceptual sense [and] should continue to form part of the UK’s solvency regime.

The Committee’s response indicates that it believes a risk margin should be held even if the UK were no longer bound by Solvency II.

However, the Committee was concerned by the PRA’s “apparent reluctance quickly to address some of the problems of the risk margin” and recommended that the PRA, “working in close collaboration with the industry, should provide a solution for the risk margin to improve its calibration”, and this should be done “irrespective of the Commission review process”.

In February 2018, the PRA (2018, page 21) responded to say that it was actively looking at steps it might take to address the risk margin. The working party understands that this included the idea of accepting the “management actions” solution proposed by the industry (see section 6.2).

However, in June 2018, Sam Woods, CEO of the PRA, wrote to the Committee (S. Woods, Reference Woods2018) to say that the PRA had decided not to take this forward, pending further clarity on the Brexit negotiations:

We have been considering our supervisory approach to the use of future risk mitigation and transfer mechanisms in a number of contexts, including the calculation of the risk margin. We have looked at this option very carefully, and think it has some merit as a solution to the problem the risk margin is causing. However, in the context of the ongoing uncertainty about our future relationship with the EU in relation to financial services we do not yet see a durable way to implement a change with sufficient certainty for firms to be able to rely on it for pricing, capital planning and use of reinsurance.

3.5.3 Industry arguments

The submissions from the insurance industry to both of the above enquiries covered similar themes. The published responses from individual UK insurers and from industry organisations where they are strongly represented – the ABI (2018), Insurance Europe (2018) and the European Insurance Chief Financial Officers Forum (CFO Forum, 2018) – were also broadly consistent.

When we describe the key proposals from the industry, these can be taken as referring to the collective response to the two enquiries from these groups.

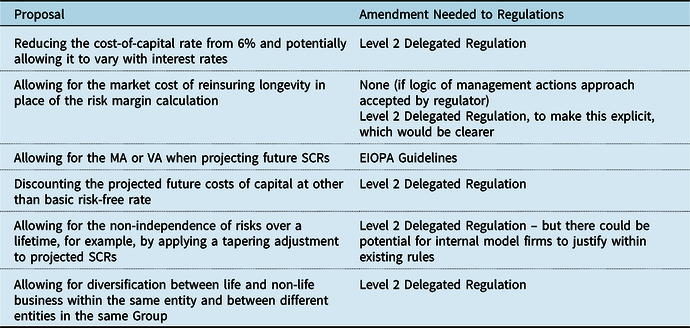

The key proposals from the industry for amendments to the risk margin were

1. reducing the cost-of-capital rate from 6% and potentially allowing it to vary with interest rates;

2. allowing for the market cost of reinsuring longevity in place of the risk margin calculation, including a mechanism by which this could be done without any need to amend the regulations;

3. allowing for the MA or VA when projecting future SCRs;

4. allowing for diversification between life and non-life business within the same entity and, more relevantly for the UK given the relative lack of composite insurers, between different entities in the same Group; and

5. allowing for the non-independence of risks over a lifetime, for example, by applying a tapering adjustment to projected SCRs.

Our analysis of these proposals is given in sections 6.1 to 6.5, respectively.

Responses to EIOPA from non-UK insurers and national industry bodies and actuarial associations outside of the UK were often different, largely in placing less emphasis on the risk margin as a key topic.

4. Survey of Insurers

4.1 Introduction

The working party has carried out a survey of selected UK life insurers, with the aim of providing insight into how the UK life insurance industry currently approaches the valuation and management of the risk margin, the main issues faced and potential future design changes.

The survey took place in the third quarter of 2018. In the period since implementation of Solvency II, the methodology and approach used by firms to measure the risk margin have largely bedded down, while the management and optimisation of it continue to date.

However, there are areas relating to the measurement of risk margin and management that are still open to debate.

The working party hopes that the results of the survey are useful in summarising industry attitudes at this point in time and as a comparator in future years.

4.2 Survey Structure

The structure of the survey was designed to capture

the key methodology points for determining the risk margin, rather than details of calculations;

the main issues being faced in managing it, particularly the volatility of interest rates; and

the main areas to re-think or modify post-Brexit.

The survey questions were therefore grouped in two parts; first on the current approaches and practices and the second on the design issues and potential changes. Appendix C details the questions we asked in the survey.

The survey was sent to the Chief Actuaries of most major life insurance groups in the UK, in particular those with material volumes of immediate annuity business. In addition, the survey was also sent to firms writing a mix of other business such as protection and unit-linked and with-profits savings business.

We attempted to keep the length of the survey reasonable and hope it was not too onerous to complete. We are grateful to those who took the time to contribute to the results.

4.3 Survey Results

The response rate is considered healthy for this type of survey. The responses have been from firms of varying sizes, which cover a wide variety of product offerings in the UK. In the interests of data protection and commercial confidentiality, individual responses have been treated in strictest confidence. For the purpose of this report, all results have been presented in an aggregate format or have been made anonymous.

The survey results on the profile of respondents and current practice are presented in this section, whereas the results on the current challenges and aspects of the risk margin where firms would like to see changes, particularly post-Brexit, are presented in section 6, where we discuss these issues and potential options.

When presenting our analysis, we have also included the context of our findings, by including a profile of respondents, where relevant.

4.4 Respondent Profile

4.4.1 Size of respondents

The survey received participation from a wide spectrum of respondents (14 responses in total) ranging from small to large businesses in terms of their in-force liabilities. We have categorised respondents by the size of their technical provisions at 31 December 2017 and the results are summarised in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Size of respondents.

We use the following definitions when referring to the technical provisions of the respondent:

Small: less than £5bn;

Medium: more than £5bn, but less than £10bn;

Large: more than £10bn.

The technical provisions include unit reserves, and are before allowance for TMTP, which mitigates the impact of the risk margin at the date of Solvency II implementation.

4.4.2 Lines of business

We asked respondents about their material lines of business.

As shown in Figure 5, unit-linked and protection were the most common lines of business offered by the respondents. There was also a broad range of other lines of business.

Figure 5. Lines of in-force business.

Although there were a few monoline respondents, most offered two or more lines of business. About 45% of the respondents offered three or more lines of business.

Firms are however expected under Solvency II to manage the impact of risk margin for new business written under the new regime. We therefore expect firms open to new business to be more active in managing the risk margin.

Consequently, we also asked the respondents about their material lines of new business.

As shown in Figure 6, unit-linked and protection were the most common lines of new business. There was also a broad range of other lines of business.

Figure 6. Lines of new business.

4.4.3 Solvency model used by respondents

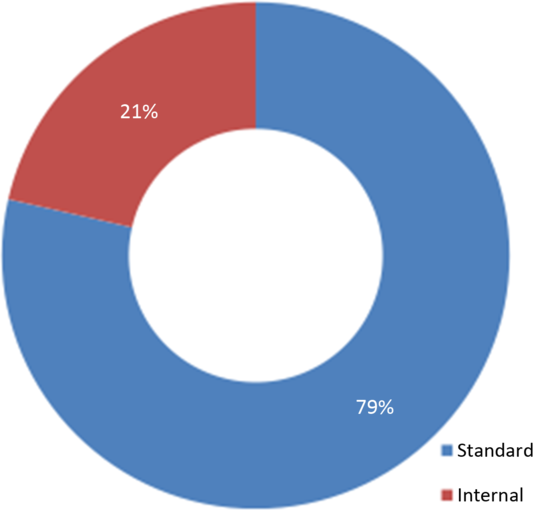

As shown in Figure 7, the standard formula was the most common model used by the respondents, although some respondents used internal models.

Figure 7. Solvency model.

The internal model respondents include those using partial internal models.

For these respondents, we also asked which risks were internally modelled. The main response is that the model is partial because some blocks of business are on the standard formula.

All respondents using internal models are large firms.

4.4.4 Risk margin measurement

One of the main inputs to the risk margin calculation is the underlying time-zero risk capital amount. The calculation of risk capital used for risk margin purposes (RM SCR) can differ from the SCR for Pillar 3 disclosure purposes. For example, the RM SCR cannot recognise the impact of the MA or VA on SCR stresses.

We asked if there is any material difference in the methodology (apart from those required by the regulations) to calculate the underlying risk capital between RM SCR and SCR for risks included in the risk margin. None of the respondents mentioned any differences – presumably other than these inherent differences.

We asked if there are any underwriting risks treated as hedgeable for risk margin. The results confirmed that all respondents, including the internal model ones, include full allowance of underwriting risk capital in their calculation.

We asked if there any market risks treated as not hedgeable or residual. We expected the internal model firms to have some allowance; however, only one respondent makes allowance for certain non-traded risks (and potentially interaction between market and underwriting risks). As expected, none of the standard formula respondents have any residual market risk capital within risk margin calculations.

We asked the respondents about their RM/RM SCR and RM/BEL ratios, and, where they offer material annuity business, to split the results by annuity and non-annuity portfolios.

The survey results confirmed that at 31 December 2017, the RM/RM SCR ratios varied from 70% to over 100% for annuity business and from 45% to 60% for non-annuity portfolios. For the same period, the RM/BEL ratios varied from 5% to 8% for annuity and from 1% to 4% for non-annuity portfolios.

The respective RM/BEL ratios at 31 March 2017 varied from 7% to 11.5% for annuity and from 1.2% to 5% for non-annuity portfolios, showing the relative sensitivity of different business to movements in interest rates. The EIOPA risk-free rates were then about 30% lower at initial durations, reducing to 15% near 10 years and 6% at 20 years.

The ratios varied materially depending on the solvency model used, with the ratios being higher for standard formula respondents compared with internal models. Similarly, the mix of business also impacted the results, with higher ratios for monoline business, presumably owing to the relative lack of risk diversification.

4.4.5 Risk margin under own assessment – Pillar 2

Pillar 2 of the Solvency II regime includes firms’ own assessments of the risks faced. We were interested in how firms view the risk margin within their Pillar 2 assessments. We therefore asked whether firms hold some form of risk allowance for non-hedgeable risks on their Pillar 2 balance sheet.

The survey showed that two-thirds of the respondents do hold a risk margin within their Pillar 2. We asked these respondents whether it is calculated on the same basis (the same one-in-200-year non-hedgeable stresses and methodology) as Pillar 1, and, if it is different, in which areas do they diverge, for example, cost of capital, risks, run-off method, discount rate, etc.

We expected the internal model firms in particular to have a different allowance for the risk margin in Pillar 2 and expected the main areas of divergence to be more realistic firm-specific cost-of-capital and discount rates. The survey revealed that 83% of respondents hold the risk margin on the same basis as Pillar 1, including all internal model respondents. Where respondents use a different basis, this mainly relates to a different discount rate being used instead of EIOPA’s risk-free rates.

Overall, we consider that it shows that firms may view the risk margin as a necessary component of the market value of liabilities, rather than an unnecessarily prudent margin or additional capital, on top of the risk capital. However, in some cases, it may reflect operational simplicity.

4.4.6 International Financial Reporting Standards

The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB, 2017) have published International Financial Reporting Standard 17 (IFRS 17), which includes a risk adjustment similar to the risk margin. Given that firms are preparing for the implementation of IFRS 17, we asked if they have considered the approach to be used for calculating the IFRS 17 risk adjustment. See section 8.1.7 for further information on the IFRS risk adjustment and a comparison with the risk margin.

The responses to this question were limited.

Three respondents had considered their approach to IFRS 17. Of these, one unit-linked insurer expected to be in line with the Solvency II risk margin and two are exploring other approaches including a confidence interval and a PAD.

A further three respondents had not considered their approach at the time of the survey.

A further three respondents either stated that they are not subject to IFRS or that they are considering moving away from IFRS. These may be non-listed or mutual insurers.

5. The Working Party’s Risk Margin Model

5.1 High-Level Summary of Model and Purpose

The working party has developed a simple model to carry out sensitivity analyses to show the volatility of the risk margin to key assumptions built in the current risk margin methodology and to assess the impact of alternatives to the current approach discussed later in the paper.

The model projects the results for a monoline annuity firm, writing immediate annuity business with no reinsurance. It projects benefit and expense cash flows for an assumed age/gender mix. Details of the model are set out in Appendix D.

The modelled SCR assumes no market and counterparty default risk (since no reinsurance is assumed) and allows for only longevity, expense and operational risks, in each case in accordance with the standard formula.

We are aware that the longevity stresses typically used by internal model firms for annuity business are somewhat larger than those required by the standard formula, because internal models stress both the mortality rate and the trend, whereas the standard formula stresses only the mortality rate. As an illustration of this, PwC (2018) states that the average increase in life expectancy at the age of 65 years resulting from the longevity stresses in internal models at 31 December 2017 is an increase of around 3 years, whereas the increase in our model is less than 2 years. Therefore, our model is likely to underestimate the amount of the risk margin for internal model firms.

The working party believes that our model is a reasonable means of illustrating simply the properties of the risk margin.

For the purpose of presentation in this paper, we have mainly used relative measures to show the impact on the risk margin, such as the percentage of BEL or SCR and/or the change in risk margin relative to December 2015.

The working party believes that the risk margin as a percentage of the modelled SCR is a useful metric, as most of the sensitivity testing and proposals considered in the paper are not likely to have any direct impact on market risk.

5.2 Base Model Results

The base position includes an allowance for MA of 100 bps in the calculation of BEL. Neither the RM SCR nor the discount factors used for the cost of capital allow for the MA. The allowance for MA relates only to the BEL used in the denominator in the ratios or in the calculation of the SCR. Unless stated otherwise, the results do not allow for transitional measures or reinsurance.

Table 1 presents the base modelled results at 31 December 2018 for key metrics. Appendix D also presents the sensitivity of base results to various changes in assumptions made.

Table 1. Base Results

5.3 Sensitivity to Interest Rates

The risk margin is particularly sensitive to changes in risk-free rates. To show this volatility, we have run the model with monthly EIOPA risk-free rates from December 2015 to December 2018 and have shown the results in section 3.1.2 for both movements in the risk margin as a percentage of the December 2015 risk margin and movement in the risk margin/BEL ratio as percentage of December 2015 risk margin/BEL ratio.

Figure 8 shows the movement in risk margin/BEL ratios for each year-end since the implementation of Solvency II, along with the sensitivity to a parallel shift of 50 bps down and up to the December 2018 curve. The Figure also shows the 12-year EIOPA spot rates, corresponding to the duration of modelled liabilities.

Figure 8. Variation of risk margin with and sensitivity to risk-free rates.

This volatility of the risk margin to interest rates represents one of the challenges in managing it in a rapidly changing interest rate environment. Interest rate changes have a dual impact on risk margin. With a reduction in the risk-free rate curve, firstly the BEL is re-valued upwards and so is the stressed BEL to calculate the individual risk capital, resulting in larger risk capital.

This effect is amplified for firms using MA or VA, as these measures are ignored for the purpose of the risk margin calculation. The BEL and stressed BEL used to calculate the risk capital for risk margin purposes cannot use the MA or VA, thereby increasing RM SCR in comparison with the SCR for Pillar 3 disclosures.

Secondly, the costs of capital are discounted at lower rates, resulting in a higher overall present value for the risk margin.

5.4 Assessment of Alternative Risk Margin Proposals

We have used the model to assess and present the financial impact of certain alternative options, and where relevant we have shown this impact relative to the base results. Furthermore, to assess whether the alternative proposals are helpful to mitigate the volatility issues highlighted in earlier sections, we have presented the results over time to show the volatility of the proposal in comparison to the base result.

The summary results are presented throughout section 6..

6. The Cost-of-Capital Method – Recalibration

In this section, we focus on suggested changes to the cost-of-capital method, based on amendments proposed by the insurance industry and also the IFoA, after Solvency II came into effect. Many of these changes were proposed in the post-implementation enquiries summarised in section 3.5.

We set out the key areas of change proposed and our views, including the results of our modelling and of our survey.

6.1 Cost-of-Capital Rate

The Level 2 Delegated Regulation, rather than the Level 1 Directive, specifies the 6% cost-of-capital rate used in the risk margin.

As stated in section 3.5.1, EIOPA (2018) focused in the review almost entirely on the cost-of-capital rate, and the conclusion was that if anything 6% was too low:

In view of the results of the CoC calculations in the range from 6.7% to 7.8%, EIOPA recommends that the currently applicable CoC rate of 6% should not be changed.

Not surprisingly, this conclusion received, and indeed continues to receive, significant pushback from the industry, who have consistently argued that 3−4% would be a more appropriate rate, as was typically used for embedded value calculations.

Table 2 sets out summaries of the key points made in support of a lower rate, EIOPA’s responses and the views of the working party relating to the responses from EIOPA.

Table 2. Proposals for a Lower Cost-of-Capital Rate

Offsetting these reductions is the view that the cost-of-capital rate could well increase following an extreme stress, that is, in the scenarios envisaged within the SCR calculation. Although not required by regulators to date, the SCR is meant to represent a stress to the full balance sheet, including the risk margin, and that firms should be required to reflect this. (Note that we are concerned here only with the cost-of-capital rate and not the cost of capital overall. It may well be that following a large stress, the non-hedgeable SCR itself reduces materially.)

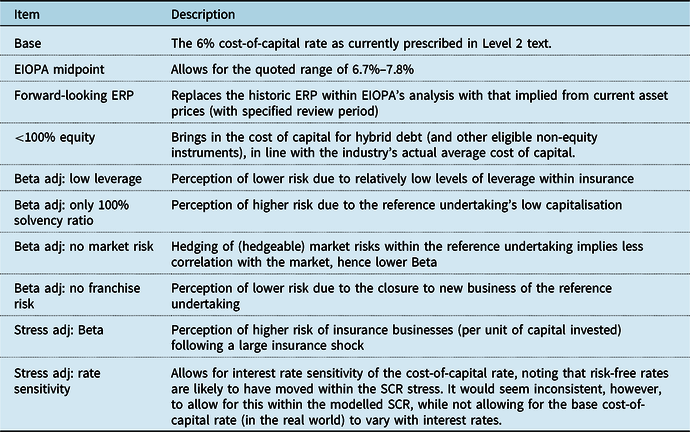

It is noted, however, that the 6% cost-of-capital rate will be reviewed as part of the 2020 EIOPA review. While we do not express a view here on the rate itself, we set out below the analysis steps that we believe should be allowed for. This is on the assumption that a cost-of-capital approach, calibrated independently of reinsurance pricing or market transaction data, is retained and is notwithstanding the various weaknesses of the cost-of-capital approach described elsewhere in this paper. Figure 9 is illustrative only and not to scale.

Figure 9. Illustration of steps that should be considered in defining the cost-of-capital rate.

Each step in Figure 9 is described in Table 3.

Table 3. Descriptions of Steps in Figure 9

The members of the working party do not have a consensus view on whether, having regard to the above factors, the current cost-of-capital rate of 6% is correctly calibrated.

A solution was also proposed and designed to reduce the sensitivity of the risk margin to interest rates, namely that the cost-of-capital rate (which it should be noted is already an excess cost over risk-free) should depend on the risk-free rate:

The Chief Risk Officers Forum (CRO Forum, Reference Forum2008, page 35) researched the cost-of-capital rate during the development of Solvency II. The Forum’s report includes

The Cost-of-Capital rate is sensitive to changes in the level of risk-free rate, increasing by 0.3% to 0.4% for every 1% increase in the risk-free rate.

This suggests that x% might be 30−40%.

The field testing of ICS described in IAIS (2018), discussed in more in detail in section 7.7, is also considering an approach where the cost-of-capital rate = 3% + risk-free rate (i.e. x% = 100% in the formula above), albeit the working party is unaware of any theoretical justification for this particular choice.

EIOPA (2018, page 347) also argued that “empirical and academic evidence to support a theoretical link between the risk-free rate and the equity risk premium is mixed” and quoted the work of Damodaran (2016), amongst others, which suggests that although long-term historic data suggest a positive relationship between the equity risk premium and the risk-free rate, more recent experience, if anything suggests no relationship or even the opposite.

We note that while allowing the cost-of-capital rate to itself vary with interest rates would reduce the sensitivity of the risk margin to interest rates, it could add to practical hedging difficulties.

6.1.1 Working party survey on cost of capital

In our survey, we asked firms if they would support making the cost-of-capital rate dynamic that is linking cost of capital with the interest rate environment and/or firms’ actual cost of capital, and the reasons why.

As shown in Figure 10, a large majority supported making the cost-of-capital rate dynamic. The respondents who did not support it explained that it may not work for their block of business – potentially making managing the risk margin more difficult.

Figure 10. Support for dynamic cost-of-capital rate.

The main points gleaned from the respondents were

Help with interest rate sensitivity – it may help with volatility or reduce the size of risk margin, possibly making volatility impacts less material.

Theoretical arguments – intuitively, it seems reasonable for the cost-of-capital rate to have some dependency on the level of market interest rates, since investment decisions are made within the wider economic context including the level of risk-free rates.

Ease of implementation – a change to the cost-of-capital rate would probably be the easiest to achieve with almost no to little change.

Potential challenges – however, depending on the how cost of capital is linked to interest rates – it may be difficult to identify suitable parameterisation of the cost-of-capital rate to achieve the desired risk margin behaviour for different lines of business. If not considered carefully, we might end up in situation where risk margin behaviour could be unintuitive, for example, a rising risk margin as interest rates increase.

6.1.2 Model results on cost of capital

Figure 11 presents the model results for relative movement of RM/BEL as a percentage of the December 2015 ratios for a change in the cost-of-capital rate from the current 6% to being calculated as 35% of risk-free interest + 5.4%, where 5.4% is chosen so that the formula provides similar results to the base at December 2015.

Figure 11. Impact of changing the cost-of-capital rate to dynamic.

The results are shown relative to the base results.

The results show that relative to the base position, the change in cost-of-capital parameters will result in lower volatility in the risk margin. The proposal results in 50% lower volatility over this time period when measured by the standard deviation of RM/BEL.

In practical terms, this alternative will result in different cost-of-capital rates being applied to the amount of capital for every period. Note that the cost-of-capital rate (based on average duration for the modelled portfolio) for December 2018 is just under 6%. However, during times of high interest rates, this alternative could also result in materially higher risk margins.

6.2 Allowance for Longevity Reinsurance/management Actions

One key argument made against the risk margin for annuity business is that longevity is, unlike some other demographic risks, largely hedgeable.

The Comité Européen des Assurances (CEA) and the Groupe Consultatif Actuariel Européen (Groupe Consultatif) define a hedgeable risk under Solvency II as (see CEA and Groupe Consultatif, 2007, page 31):

A risk associated with an asset or an obligation that can be effectively neutralised by buying or selling a market instrument (or engaging in a contract with a third party in an arm’s length transaction under normal business conditions), whose value is expected to change in such a way as to offset the change in value of the asset or liability caused by the presence of the risk.

Longevity risk arguably falls within this definition.

However, although the exclusion of hedgeable risks was a major criterion in the development of the Solvency II risk margin, the wording of the regulations took a different route. The concept of hedgeable risk is not mentioned in the Level 1 Directive or Level 2 Delegated Regulation at all. Rather, in the Level 2 Delegated Regulation, the SCR used in the risk margin projections is calculated under the assumptions that:

market risk is minimised (by de-risking assets and, when required, by hedging), but

the underwriting risk is the same as for the transferred business, allowing for reinsurance in-force.

Therefore, under the current Solvency II regulations, longevity risk cannot be excluded from the risk margin even if it is considered to be hedgeable.

When the ABI gave its initial evidence to the Treasury Committee, it revealed that the industry, in particular Legal & General, had made a detailed proposal to the PRA to allow for the ability to reinsure longevity in the risk margin within the constraints of the Level 1 and Level 2 text.

At the Treasury Committee’s request, the detailed proposal was published as part of the further written evidence (ABI, 2017).

The proposal was outlined to EIOPA in ABI (2018).

In summary, this involves an insurer approving a management action that provides that it would seek reinsurance to cover certain liabilities in specifically defined circumstances, namely when it de-risks its assets.

Owing to the provision in the Delegated Regulation that the reference undertaking is assumed to adopt management actions consistent with those of the insurer, those defined circumstances would be deemed to occur upon the transfer to the reference undertaking, and therefore, the reference undertaking would be treated for the purposes of the risk margin calculation as having put in place longevity reinsurance in line with the management action.

That management action would be reflected in determining the reference undertaking’s SCR for the purposes of calculating the risk margin.

In practice therefore, the longevity risk part of the risk margin would be replaced by the expected cost of reinsurance, allowing for a period to put the reinsurance in place.

This would have the benefit of producing a risk margin consistent with the market price for longevity risk, which would seem consistent with the intention of the risk margin.

As a consequence:

the resulting risk margin would typically be lower than the present method, in current conditions; as indicated in section 3.1.3, we understand anecdotally that the market cost of reinsurance for a typical annuity allows for around 5% margin above the BEL, depending on the characteristics of the portfolio;

the resulting risk margin would be significantly less sensitive to interest rates; and

this would also avoid artificial incentives to transfer risk outside of the UK/EU.

The disadvantages of the approach, which we understand that the ABI acknowledged in its discussions with the PRA and intended to address as part of any implementation, include

technical provisions would potentially be dependent on fluctuations in reinsurance market pricing. Insurers might argue for a through-the-cycle average given the long-term nature of the risk margin calculation but that would then add back incentives to transfer risk in times when market pricing was particularly competitive;